Abstract

Agrin is a key organizer of acetylcholine receptor (AChR) clustering at the neuromuscular junction. The binding of agrin to laminin is required for its localization to synaptic basal lamina and other basement membranes. The high-affinity interaction with the coiled-coil domain of laminin is mediated by the N-terminal domain of agrin. We have adopted a structurally guided site-directed mutagenesis approach to map the laminin-binding site of NtA. Mutations of L117 and V124 in the C-terminal helix 3 showed that they are crucial for binding. Both residues are located in helix 3 and face the groove between the β-barrel and the C-terminal helical segment of NtA. Remark ably, the distance between both residues matches a heptad repeat distance of two aliphatic residues which are solvent exposed in the coiled-coil domain of laminin. A lower but significant contribution originates from R43 and a charged cluster (E23, E24 and R40) at the open face of the β-barrel structure. We propose that surface-exposed, conserved residues of the laminin γ1 chain interact with NtA via hydrophobic and ionic interactions.

Keywords: agrin/basal lamina/coiled coil/laminin/neuromuscular junction

Introduction

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is required for precise, rapid and orderly communication between motor neurons and muscle cells. It is composed of the pre- and post-synaptic specializations, separated by a synaptic cleft that is occupied by the synaptic basal lamina. Agrin, a key organizer for the induction of postsynaptic specializations at the NMJ (Ruegg and Bixby, 1998) is stably associated with the mature synaptic basal lamina (Reist et al., 1987). This local immobilization of agrin derived from motor neurons is believed to be important for the maintenance of postsynaptic structures (McMahan, 1990).

Agrin is a multi-domain heparan sulfate proteoglycan with an apparent mol. wt of 400–600 kDa on SDS–PAGE. The most N-terminal domain (NtA) binds to the basal membrane component laminin (Denzer et al., 1998). It is followed by nine follistatin-like domains (FS) that are homologous to the Kazal type of protease inhibitors (Patthy and Nikolics, 1993). The C-terminal half of agrin comprises three laminin G-like domains (LamG) posses sing two sites, A/y and B/z, which are subject to alternate splicing. The AChR aggregation activity of agrin is strongly modulated by the presence of the insert at both sites (Burgess et al., 1999).

Laminins are ubiquitous components of the tight network of glycoproteins, collagen IV and proteoglycans in basement membranes (Yurchenco et al., 2002). Laminin molecules consist of three chains (α, β and γ) that are interlinked by an extended coiled-coil domain, forming the long arm of the cruciform-shaped heterotrimer (Beck et al., 1990; Timpl and Brown, 1994, 1996; Maurer and Engel, 1996). By a combination of electron microscopy (Denzer et al., 1998) and mutational analysis (Kammerer et al., 1999) the binding site of laminin to NtA was localized to the central region of the ∼60-nm-long arm of laminin-1. The agrin-binding site in laminin-1 maps to a sequence of 20 residues within the γ1 chain (Kammerer et al., 1999). Interestingly, a coiled-coil conformation of the binding site appears to be necessary for the interaction with agrin. Sequences of the chains exhibit the typical heptad repeat (abcdefg)n of coiled-coil structures in which residues in positions a and d are restricted to the core, while residues in other positions are usually of charged and polar nature and exposed to the surface (Cohen and Parry, 1990). Based on spectroscopic data and hydrodynamic analysis (Beck et al., 1990), interruptions within the trimeric coiled coil of laminin in the region of the binding site are likely, but further predictions are hampered by the so far unknown correct register between all three chains.

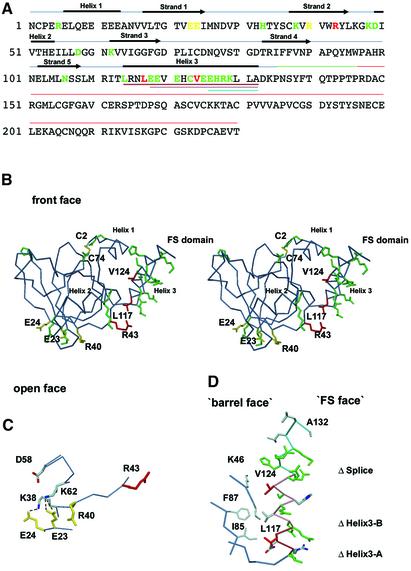

In contrast, the X-ray structure of the NtA domain, which mediates high-affinity interaction of agrin with the coiled-coil domain of laminin-1, was solved to 1.6 Å resolution (Stetefeld et al., 2001). The structure revealed a β-barrel fold flanked by α-helices at both termini which are characterized by a high content of charged amino acids (Figure 1). The C-terminal α-helix of chicken NtA (helix 3) contains a seven-residue splice insert comprising residues E126–A132, with an as yet unknown function. Motor neurons in developing spinal cord contain agrin transcripts that include the splice insert. However, the majority of agrin mRNA in non-neuronal tissues is characterized by the absence of the seven-residue insert (Denzer et al., 1995; Tsen et al., 1995).

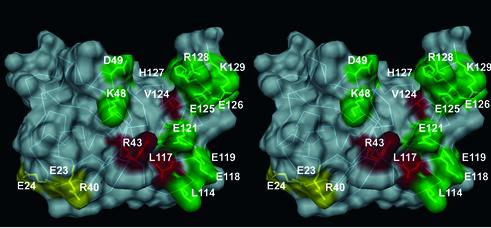

Fig. 1. Mapping of the laminin-binding epitope on NtA. (A) Structure-sequence-alignment of NtA-FS. Domain boundaries for NtA (blue bar), the linker between NtA and FS domain (green bar) and the FS domain (red bar) are highlighted. Secondary structural elements for NtA are indicated above the sequence alignment. β-strands and α-helices are labeled sequentially from strands 1 to 5 and helices 1 to 3. Deletions performed at helix 3 are shown below the sequence and are colored brown for ΔHelix3-A (Δ114–132), pink for ΔHelix3-B (Δ118–132) and cyan for ΔSplice (Δ126–132). Mutated residues are shown in different colors (see also Table I). Mutated residues that cause a significant reduction in laminin-1 binding are in red; those that show a less significant contribution are in yellow and those that cause only a slight or no change in affinity are in green. (B) Stereo Cα trace with all residues mutated shown in the color scheme of (A). Only mutated amino acid residues showing at least a 20-fold decrease in binding are labeled and the very N-terminal disulfide bridge (Cys2–Cys74) is shown in atom color type. (C) Detailed view of the charged cluster at the open face. The triple combination of E23A E24A R40A is shown in yellow. Hydrogen bond distances between E23–K38 and E24–K62 are shown as dotted lines. (D) Detailed view of helix 3 and hydrophobic cluster. Mutated residues are colored as in (A), otherwise in atom color type. The Cα trace of the hydrophobic cluster at the barrel face and the connector between the β-barrel and helix 3 (L109–L114) are shown in steel blue. The Cα trace of deletions of helix 3 is shown according to (A).

In the current study, we have mapped the laminin-binding site of agrin. Based on the high-resolution X-ray structure of NtA, we have constructed a number of point mutants and deletions and expressed them in conjunction with the first FS domain of agrin (NtA-FS) (Figure 1). The mutant proteins were tested for stability and binding to laminin-1. Solid-phase binding assays and competition assays with 125I-labeled NtA-FS were used to quantify the effect of the mutations on the binding to laminin-1. The results show that the interaction of laminin-1 with the N-terminal domain of agrin is a protein–protein interaction of high affinity (KD ∼ 5 nM), mediated by the C-terminal helix 3 as the primary binding site and charged residues at the open face of the β-barrel as an auxiliary site.

Results

Expression and characterization of agrin fragments and mutants

In previous studies, either (i) full-length agrin, (ii) a construct that encodes an agrin fragment comprising NtA and the first FS domain (NtA-FS) or (iii) a fragment that lacks the first 130 amino acids from the N-terminus (cΔNAgrin) was used to investigate the interaction between agrin and laminin (Denzer et al., 1995, 1997, 1998). These data demonstrated that the very N-terminal domain of agrin (NtA) is indispensable for binding of agrin to laminin. However, it remained elusive whether the binding site for laminin is located on NtA alone, or whether the FS domain also contributes. Therefore, the single NtA-core domain composed of amino acid residues 1–132 and the NtA-FS (for sequence see Figure 1A) were expressed in HEK 293 cells and binding affinity for laminin-1 was determined (Table I; Figure 2). The data show similar binding activities for both NtA and NtA-FS, indicating that for binding of agrin to laminin-1, the NtA domain alone is sufficient. For the present studies, NtA-FS was used for mutagenesis due to its higher solubility. However, the design of mutants was restricted to the NtA domain of the NtA-FS construct. For all recombinant proteins used in the present work comprising NtA-FS, the natural signal sequence of chick agrin was used while the NtA was expressed with the BM-40 signal sequence. It was demonstrated by N-terminal sequencing of NtA-FS that the first residue of the NtA domain is asparagine (Figure 1A), a feature that previously was only predicted by the algorithm of von Heijne (1986).

Table I. Effect of mutations of NtA-FS on its laminin-1 binding activity.

| Mutant | IC50 (nM)a | Loss of activityb | Half-maximal bindingc | Relative bindingd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NtA-FS | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| NtA | 7 | 1.4 | 3 | 1 |

| R5A | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1.6 |

| H33A | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1.6 |

| N106A | 50 | 10 | 20 | 6.5 |

| E23A E24A R40A | >100 | >20 | >50 | >16 |

| K38A D58A K62A | 10 | 2 | 10 | 3.3 |

| R43A | >200 | >40 | >200 | >65 |

| K48A | 10 | 2 | 10 | 3.3 |

| D49A | 40 | 8 | 20 | 6.5 |

| ΔHelix3-A (Δ114–132) | >1000 | >200 | >500 | >166 |

| ΔHelix3-B (Δ118–132) | >1000 | >200 | >500 | >166 |

| L114F | 20 | 4 | 20 | 6.5 |

| L117A | >500 | >100 | >500 | >166 |

| E118A | 10 | 2 | 20 | 6.5 |

| E119A | 9 | 1.8 | 20 | 6.5 |

| E121A | 6 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.6 |

| C123A | 8 | 1.6 | 5 | 1.6 |

| V124D | >300 | >60 | >300 | >100 |

| E125A | 7 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.6 |

| ΔSplice (Δ126–132) | 70 | 14 | 10 | 3.3 |

| E126A | 10 | 2 | 20 | 6.5 |

| H127A | 10 | 2 | 5 | 1.6 |

| R128A | 7 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.6 |

| K129A | 30 | 6 | 5 | 1.6 |

aIC50 values were determined by a radioligand competition assay.

bLoss of activity refers to the ratio IC50 mutant/IC50 NtA-FS.

cThe concentration (nM) required to achieve half-maximal binding determined by ELISA.

dRelative binding affinities refer to the ratio of half-maximal binding of mutant/NtA-FS. Single point mutations with a loss of activity >10- to 14-fold are defined as significant, whereas the triple combination is defined as less significant.

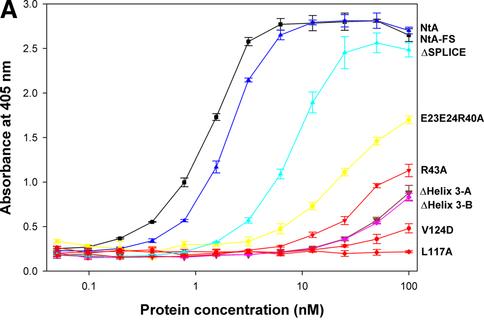

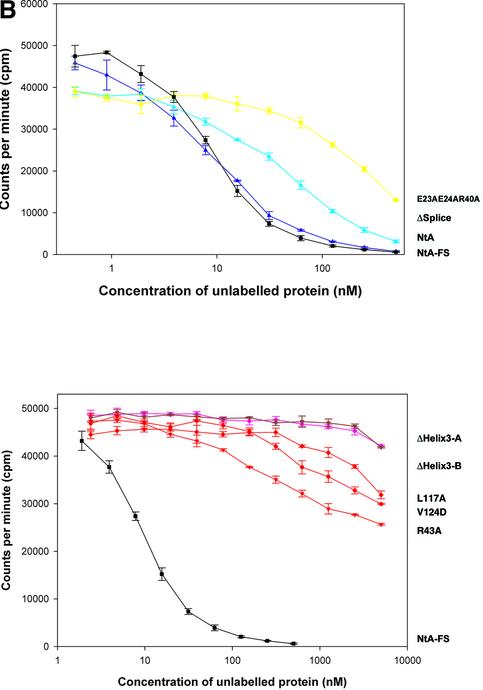

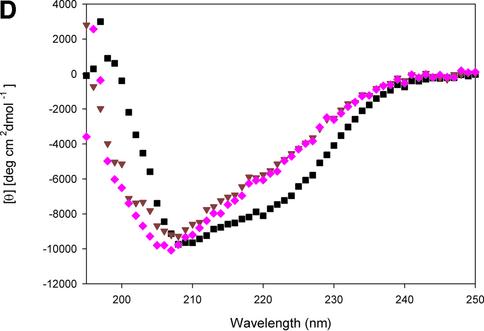

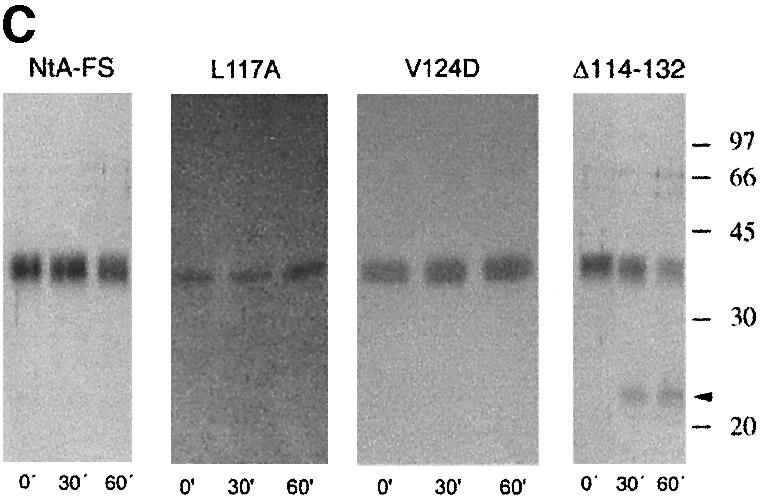

Fig. 2. Solid-phase assay of NtA or NtA-FS binding to immobilized laminin-1, radioligand competition assay and stability determined by trypsin digestion and CD spectroscopy. (A) Binding of NtA, NtA-FS and mutants within the NtA domain to laminin-1. Soluble ligands were NtA-FS (black squares), NtA (purple triangles), ΔSplice (blue triangles), E23A E24A R40A (yellow squares), R43A (bright red triangles), ΔHelix3-A (dark red triangles), ΔHelix3-B (pink diamonds), L117A (red diamonds) and V124D (red circles). Bars indicate standard deviations of three measurements. (B) Binding of radiolabeled NtA-FS (10 nM) to immobilized laminin-1 was competed with NtA, NtA-FS and mutants of NtA-FS within the NtA domain at different concentrations. Symbols are as in (A). (C) SDS–PAGE analysis after trypsin digestion at different time periods. The native NtA-FS and both single point mutants within helix 3 (L117A and V124D) were stable to trypsin cleavage. Exceptions were the deletion of helix 3, which showed the appearance of an additional band indicated by the arrowhead (only ΔHelix3-A is shown). Molecular weights determined by protein markers are indicated. (D) CD spectra of NtA-FS (squares), ΔHelix3-A (triangles) and ΔHelix3-B (diamonds) recorded in Tris-buffered saline at protein concentrations of 10 µM for the NtA-FS and 6 µM for both the helix 3 deletions.

In total, 20 mutants were analyzed either individually or in triple combinations in order to map the binding site for laminin (Table I; Figure 2). These experiments were completed by performing two deletions of helix 3 (ΔHelix3-A: Δ114–132 and ΔHelix3-B: Δ118–132) and use of the ΔSplice variant (Δ126–132) at the C-terminus of NtA. All of these proteins harboring the mutations were obtained from serum-free culture medium of transfected HEK 293 cells in yields comparable to that of the wild-type NtA-FS protein (1 mg/l of culture medium), indicating that the mutations did not interfere with proper folding.

Purity was checked by SDS–PAGE, and bands with an apparent mol. wt of 22 kDa, 27 kDa for NtA and 35 kDa for NtA-FS were observed (data not shown). The additional band observed in the case of NtA might reflect heterogeneity in glycosylation (Hohenester et al., 1999; see also Supplementary data available at The EMBO Journal Online). Proper folding was tested by resistance to limited tryptic digestion according to established methods (Fox et al., 1991; Pokutta et al., 1994) together with circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Figure 2C and D). All mutations exhibited a similar stability as wild-type NtA-FS, with the exception of both deletions within the C-terminal helix 3 (Figure 2C). The cleavage site was located by N-terminal sequencing, after residue R111 for ΔHelix3-A and R115 for ΔHelix3-B, respectively. These data indicate that point mutations did not cause unfolding of NtA-FS but rather deletions at helix 3 result in an increased accessibility of trypsin to previously inaccessible sites. The various mutants and deletions were examined for their ability to bind immobilized laminin-1 in solid-phase binding assays and in competition assays with 125I-labeled NtA-FS protein (Table I; Figure 2). This binding could be inhibited by low concentrations of ∼5.0 nM NtA-FS (see Materials and methods). The two binding assays (ELISA and radioligand competition assay) showed similar results. This also held true for all other mutants investigated.

Mapping of the laminin-binding region of NtA by site-directed mutagenesis

The design of mutants was guided by the three-dimensional structure of NtA and commenced on the basis of potential sites proposed in this work (Stetefeld et al., 2001). An attractive possibility is an interaction of the α-helical coiled-coil region of laminin with one of the α-helices that start (helix 1) or terminate (helix 3) the NtA domain (Figure 1). However, deletion of the N-terminal α-helix 1 (Δ6–12) had no effect on laminin binding (Stetefeld et al., 2001). In contrast, a deletion of α-helix 3 (Δ114–132), or part of this helix (Δ118–132), led to an almost complete loss of binding (Table I; Figure 2). To analyze this primary binding site in more detail, 12 mutants of helix 3, which forms a spacer between NtA and the following FS domain, were produced (Figure 1B and D). These included changes in charge (for E118, E119, E121, E125, E126, H127, R128 and K129) and in hydrophobicity (for L114, L117, C123 and V124). Only two point mutations, L117A and V124D, resulted in a dramatic loss of binding affinity. These results clearly indicate a predominant role of residues at the ‘barrel face’ of helix 3, in contrast to solvent-exposed charged residues at the ‘FS face’, which is likely to be the region where NtA is covalently attached with the follistatin domain (Figure 1B and D).

In order to analyze the possible function of the splice insert, the binding affinity of ΔSplice NtA-FS (Δ126–132) was analyzed, and revealed only a moderate loss of activity in comparison with NtA-FS containing the seven-residue insert (Table I). This is consistent with the observation that mutations of residues within the splice insert (E126A, H127A, R128A and K129A) showed only a minor effect on binding strength.

Of all point mutations at the β-barrel core domain, only replacement of R43 facing the groove between helix 3 and the β-barrel (Figure 1B) showed a similar dramatic effect as the mutations of L117 and V124 in helix 3 (Figure 2). This second region of mutational analysis included a triple mutation of a charged cluster of residues E23, E24 and R40 at the open face that caused a 16- to 20-fold decrease in binding affinity. The charged cluster (E23, E24, K38, R40, D58 and K62) that had been proposed as a potential binding site on a structural basis (Stetefeld et al., 2001) is closely spaced and in proximity to the groove between helix 3 and the core (Figures 1B, C and 3).

Fig. 3. Surface presentation of the laminin-binding epitope of NtA in stereo view. The protein is shown by van der Waals spheres in a semi-transparent presentation. The molecular surface is shown in gray and all mutated residues are colored according to the scheme in Figure 1. The Cα trace and all marked residues are underlined.

Finally, a mutation was designed to test for the possible effect of glycosylation on laminin binding. N106 is the only predicted N-glycosylation site in NtA (Denzer et al., 1995). Its substitution by alanine had only a very moderate effect on laminin binding (Table I), suggesting that N-glycosylation is not essential for this function. The finding is supported by enzymatic deglycosylation of NtA-FS, which led to a small increase in electrophoretic mobility in SDS–PAGE (data not shown), but to no significant decrease in the binding strength to laminin.

Discussion

The interaction between laminin and agrin is essential for synapse formation in the peripheral nervous system and, in particular, in muscle (Burgess et al., 2000). It may also play a role in other sites in the extracellular matrix for stabilization and interactions of basement membranes (Sugiyama et al., 1997; Burkin et al., 2000). The agrin-binding site of laminin-1 was found to reside in a 20-residue-long region of the γ1 chain in the long arm domain that has a three-stranded α-helical coiled-coil conformation (Kammerer et al., 1999). The α1 and β1 chains of laminin-1 were shown to contribute to a lesser extent to binding, and the maintenance of a proper coiled-coil structure was a prerequisite for binding (Kammerer et al., 1999). It may be expected from these data that agrin binds to all laminins that contain a γ1 chain, with variations in affinity imposed by the other chains. Laminin-1 is an embryonic form of the laminins (Ekblom, 1981), whereas laminin-2 and laminin-4 are found at later stages of skeletal myogenesis. These three laminins contain the γ1 chain (Timpl and Brown, 1994) and this holds true for the majority of the 12 laminins known today (Colognato and Yurchenco, 2000). No binding is thus expected to laminin-5 with its γ2 chain, because of the non-conserved binding motif in γ2 (Figure 4). Furthermore, binding was shown to be strongest for laminin-4 followed by laminins-1 and -2 (Denzer et al., 1997). Differential tissue distributions of laminins may therefore regulate agrin binding.

Fig. 4. Sequence alignment of different laminin γ chains. The experimentally determined agrin-binding site comprises a 20-residue sequence (Kammerer, 1999). The heptad repeat pattern of residues in a and d position is shown in purple. Charged amino acid residues are in red (negative charge) and blue (positive charge). Both alanine residues (A1305 and A1312), which are flanked by leucines and show an unusual localization at position f (solvent exposed), are drawn in green.

To demonstrate that NtA alone mediates the agrin– laminin interaction, binding activities of NtA and NtA-FS were compared and revealed identical values for both proteins (Table I). Together with the N106A mutant, these experiments clearly demonstrate that the high-affinity protein–protein interaction (Kd ∼ 5 nM) is mediated exclusively by NtA and without involvement of attached carbohydrate chains.

The interpretation of the mutagenesis data in the context of the crystal structure of chicken NtA strongly indicates a major primary (α-helix 3) and a secondary (lower part of the charged cluster and R43 at the open face) binding site for laminin (Figures 1 and 3). Whereas single point mutations of two residues at helix 3 (L117A and V124D) together with the single R43A mutant result in a strong decrease in binding (40- to 100-fold), a triple mutation of E23A E24A R40A shows only a moderate loss of binding (20-fold; Table I). The lower part of the charged cluster together with R43 forms a narrow, almost linear array of charged residues at the surface of the β-barrel core domain (Figure 1C). Whereas salt bridges can be formed between K38–E24 and K62–E23 (average hydrogen bond distance of 3.3 Å) to stabilize antiparallel β-strands S1 and S2 of the β-barrel core, neither R40 nor R43 is complexed by solvent molecules or involved in side-chain interactions. The crucial residues of helix 3 (L117 and V124) are located on one side of the C-terminal α-helix 3 (barrel face) pointing to a groove formed between the β-barrel core domain and helix 3 (Figures 1D and 3). The major role of L117 is emphasized by the unusual positioning towards the exterior without stabilization effects to neighboring residues, indicating a direct binding partner for laminin-1.

A comparison of laminin sequences of γ chains from mouse, rat and human within the mapped binding region for NtA shows that they are highly conserved for γ1, but rather divergent for γ2 chains (Figure 4). Previous studies have demonstrated that the γ2 chain of laminin is not effective in competition assays with laminin-1 (Kammerer et al., 1999). To determine potential sites of interaction with an intact heterotrimeric coiled coil, a laminin model based on trimeric GCN4 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1GCM; Harbury et al., 1993] was docked to the globular NtA domain using the program FTDOCK (Gabb et al., 1997; Figure 5).

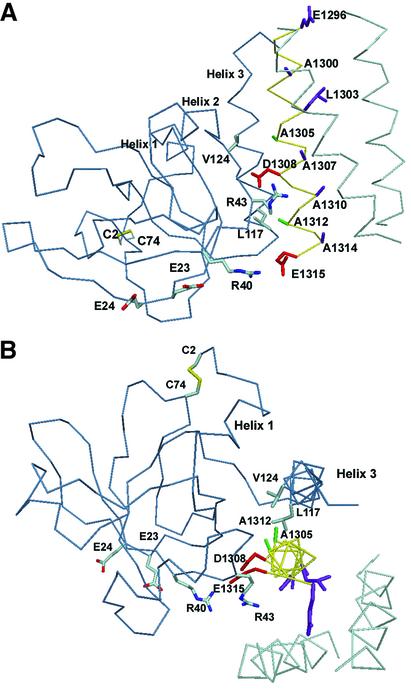

Fig. 5. Model of NtA complexed with laminin in two different views. The Cα trace of NtA is shown in blue, laminin in cyan and γ1 chain in yellow. Residues of NtA that mediate the high-affinity binding are labeled and colored according to atom type. The color scheme for atoms of laminin is the same as in Figure 4. Beside electrostatic fixations via R43 (with D1308) and R40 (possible salt bridge with E1315), the equidistant aliphatic residues at helix 3 (L117 and V124 with a Cα–Cα distance of 10.6 Å) and at the solvent-exposed surface of the γ1 chain (A1305 and A1312 separated by 10.7 Å) contribute to the high-affinity binding.

The binding region of the γ1 chain within the three-stranded coiled coil of laminin can be fitted well into the groove facing helix 3 of NtA (Figure 5B). Since the distance between L117 and V124 exactly matches the seven-residue interspace between A1305 and A1312 of the laminin γ1 chain (Figure 4), an interaction is a likely possibility. The interaction of both aliphatic and solvent-exposed residues of the γ1 chain with V124 and L117 places the nearby D1308 and E1315 in a position for possible ionic interactions with R43 and R40 from NtA, respectively (Figure 5A). Two features of the model of the complex are certainly correct, namely the placement of the laminin-binding site into the groove and the importance of helix 3 of NtA for the interaction with the coiled-coil structure. Based on our data, we propose that laminin binding is dependent on a combination of hydrophobic and ionic interactions (Figure 5).

Despite the high content of charged residues (>40% of all amino acid residues), ionic interactions of α-helix 3 are not detectable either with the β-barrel core domain or with the adjacent N-terminal helix 1. As the primary laminin-binding site, helix 3 shows a remarkable potential of spatial flexibility, and a short linker arm (L109–L114) forms the connector between the β-barrel and helix 3 that would facilitate a hinge-like motion of the C-terminal helix as a rigid body (Figure 1D). As a consequence, helix 3 can be described as a spacer linking NtA and FS domains.

The detailed model shown in Figure 5 is suggestive but may be open to modifications. The model is based entirely on interactions with the α-helix formed by the γ1 chain. However, it can not be excluded that, for example, R43 in NtA interacts with a negatively charged residue in the α- or β-chains, which were shown to be of secondary importance in binding (Kammerer et al., 1999). This problem can only be approached with a three-dimensional structure of the relevant regions of the coiled-coil domain of laminin. Our model presented here was designed assuming that the coiled-coil structure of laminin conserves its native three-stranded conformation upon binding. It is known, however, that a coiled coil may adapt to a new environment by means of a conformational change. It has been shown that the heterodimeric complex of the coiled-coil domain of cFos and cJun binds the DNA duplex like a pair of forceps (Glover and Harrison, 1995). If this is also true for the agrin-binding site in laminin, an opening of the coiled-coil structure and replacement of one of the laminin chains by helix 3 might be a possible mechanism.

Finally, it should be mentioned that the structure of a complex between a globular protein domain and a fibrillar coiled-coil structure is of general importance. Only a few interactions of this type have been defined for which structural information exists (Mayr et al., 1996; Sibanda et al., 2001). The X-ray structure of the complexin– SNARE complex has only recently been solved to atomic resolution (Chen et al., 2002). Complexin binds in an antiparallel α-helical conformation to synaptobrevin and syntaxin helices of the SNARE motif. Binding of complexin causes only minimal structural changes within the four parallel, highly twisted α-helices formed by the SNARE motif.

Thus, the ideal approach would be the co-crystallization of complexes of the two interacting domains. To achieve this aim, three-stranded laminin fragments containing the relevant regions of the α- and β-chains, in addition to the already characterized γ1 chain, have to be prepared. Work in this direction is in progress.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of NtA and NtA-FS

The construct pcN25 7Fc (Denzer et al., 1997) was used as a template to generate the cDNA construct encoding NtA and NtA-FS by PCR using Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs). Primers used for NtA were NtA 5′-GAATTCGCTAGCGGACGATGACGACAAAAACTGCCCCGAACGGGAGC and NtA 3′-GGATCCGCGGCCGCAGCAAGAAGCTTCCTATGTTCTTC and were cloned into the expression vector C-His pCEP-Pu in-frame to the BM-40 signal peptide (Kohfeldt et al., 1997). This vector included the BM-40 UTR (including a Kozak sequence), the BM-40 signal peptide for proper secretion in the culture medium and a C-terminal His6 tag. Primers used for NtA-FS were NtA-FS 5′-GGTACCGCTAGCGGGGCTGCGGGCGATGG and NtA-FS 3′-TGTAGGATCCCTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGAGATCTCGTCACCTCTGCACAGGGG. The reverse primer was designed to code for a stretch of His6 tag followed by a stop codon, and cloned into pCEP-Pu vector (Kohfeldt et al., 1997). Sequences were verified by dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (ABI). Transfection of HEK 293 cells was carried out as described, and purified on a Ni2+ NTA–agarose (Qiagen) column according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified fractions were identified by SDS–PAGE, pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl. Both NtA and NtA-FS migrated abnormally on SDS–PAGE. The calculated mol. wts of NtA and NtA-FS were 14 and 25 kDa, respectively.

Construction of expression vectors encoding mutant proteins

NtA-FS was used as a template to introduce mutations based on oligonucleotide primers by PCR. Deletions were introduced by designing forward and reverse primers with overlapping 5′ ends and encoding sequences on either side of the deletion (primer sequences are available on request). PCR was performed with the reverse and forward primers in combination with NtA-FS 5′ and NtA-FS 3′ to yield 5′ and 3′ fragments, respectively. The gel-purified fragments were fused by annealing overlapping ends and amplified with NtA-FS 5′ and NtA-FS 3′ to yield the final product. Single point mutations were introduced by designing appropriate internal overlapping primers. Multiple point mutations were introduced by performing PCR on the product obtained from single point mutation. The same protocol detailed above was followed to generate the final product. The inserts were cloned into the pCEP-Pu vector and sequences confirmed by dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (ABI). HEK 293 cells were transfected as described previously and purified as described for NtA-FS.

Solid-phase binding assays

Laminin-1 was purified from mouse Engelbreth–Holm–Swarm sarcoma. Enzyme-linked binding assays were performed with 100 µl of laminin-1 (10 µg/ml) in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer pH 9.6, immobilized on 96-well plates (Falcon) by absorption overnight at 4°C. After blocking with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), wells were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated with different dilutions of NtA-FS, or corresponding mutants. The wells were washed in the same buffer and incubated with primary antibody (Dianova GmbH) against the His6 tag at the C-terminus of the protein. Goat anti-mouse IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab Inc.) was used as the secondary antibody. The color was developed using 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonate(6)] (ABTS; obtained from Roche) as substrate, incubated for 1 h and the absorbance measured at 405 nm.

For radioligand binding assay, iodination of NtA-FS was performed as described previously (Gesemann et al., 1996). Laminin-1 was diluted to 10 µg/ml with 50 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer pH 9.6 and immobilized on microtiter plates (Falcon) by overnight incubation at 4°C. Blocking was carried out for 1 h with PBS pH 7.4, containing 1 mg/ml BSA and 2% FCS. After three washes with PBS, the unlabeled NtA, NtA-FS or mutants of NtA-FS in PBS containing 3% BSA was added as competitor, followed by addition of 10 nM iodinated NtA-FS. After washing four times with PBS, radioactivity in each well was measured in a gamma counter.

Trypsin digestion

Protein samples (5–20 µM) were incubated with 5 U trypsin/µmol protein at room temperature in 50 mM Tris–HCl containing 200 mM NaCl. The reaction was stopped after 30 min and 1 h by incubating the sample in SDS–PAGE loading buffer for 5 min at 95°C. The proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and visualized by silver staining.

CD spectroscopy

An Aviv 62DS CD spectropolarimeter was used with thermostated 1 mm quartz cuvettes. Each spectrum was the average of six scans. Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) was used as buffer. The mean molar residue ellipticity Θ (in degrees cm2/dmol) was calculated on the basis of a mean residue mol. wt of 110 Da.

Molecular modeling

Docking of NtA (PDB code 1JC7; Stetefeld et al., 2001) with laminin-1 using a trimeric coiled coil (PDB code 1GCM; Harbury et al., 1993) was performed using FTDOCK (Gabb et al., 1997). Only side chains of R40 and R128 of NtA were shifted slightly and refined in a rotamer library to allow a close fit of the laminin-1 model into the groove. The homology model of laminin was generated using SWISS-Model. Because the correct registering of the trimeric coiled coil in laminin is unknown, only the amino acid sequence of the γ1 chain was used for one chain. A polyalanine model was used to represent the α- and β-chains. The lowest energy docked structures were subject to 100 cycles of unrestrained Powell minimization using CNS (Brunger et al., 1998). Harmonic restraints were imposed on the protein atoms (3 kcal/mol Å2) with increased weight (20 kcal/mol Å2).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Suat Oezbek for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grant 3100-049281.96 to J.E. from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

- Beck K., Hunter,I. and Engel,J. (1990) Structure and function of laminin: anatomy of a multidomain glycoprotein. FASEB J., 4, 148–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R.W., Nguyen,Q.T., Son,Y.J., Lichtman,J.W. and Sanes,J.R. (1999) Alternatively spliced isoforms of nerve- and muscle-derived agrin: their roles at the neuromuscular junction. Neuron, 23, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R.W., Skarnes,W.C. and Sanes,J.R. (2000) Agrin isoforms with distinct amino termini: differential expression, localization, and function. J. Cell Biol., 151, 41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin D.J., Kim,J.E., Gu,M. and Kaufman,S.J. (2000) Laminin and α7β1 integrin regulate agrin-induced clustering of acetylcholine receptors. J. Cell Sci., 113, 2877–2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Tomchick,D.R., Kovrigin,E., Arac,D., Machius,M., Sudhof,T.C. and Rizo,J. (2002) Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron, 33, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C. and Parry,D.A. (1990) α-helical coiled coils and bundles: how to design an α-helical protein. Proteins, 7, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H. and Yurchenco,P.D. (2000) Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev. Dyn., 218, 213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzer A.J., Gesemann,M., Schumacher,B. and Ruegg,M.A. (1995) An amino-terminal extension is required for the secretion of chick agrin and its binding to extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol., 131, 1547–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzer A.J., Brandenberger,R., Gesemann,M., Chiquet,M. and Ruegg,M.A. (1997) Agrin binds to the nerve–muscle basal lamina via laminin. J. Cell Biol., 137, 671–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzer A.J., Schulthess,T., Fauser,C., Schumacher,B., Kammerer,R.A., Engel,J. and Ruegg,M.A. (1998) Electron microscopic structure of agrin and mapping of its binding site in laminin-1. EMBO J., 17, 335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekblom P. (1981) Formation of basement membranes in the embryonic kidney: an immunohistological study. J. Cell Biol., 91, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J.W. et al. (1991) Recombinant nidogen consists of three globular domains and mediates binding of laminin to collagen type IV. EMBO J., 10, 3137–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabb H.A., Jackson,R.M. and Sternberg,M.J. (1997) Modelling protein docking using shape complementarity, electrostatics and biochemical information. J. Mol. Biol., 272, 106–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesemann M., Cavalli,V., Denzer,A.J., Brancaccio,A., Schumacher,B. and Ruegg,M.A. (1996) Alternative splicing of agrin alters its binding to heparin, dystroglycan, and the putative agrin receptor. Neuron, 16, 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover J.N. and Harrison,S.C. (1995) Crystal structure of the heterodimeric bZIP transcription factor c-Fos–c-Jun bound to DNA. Nature, 373, 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury P.B., Zhang,T., Kim,P.S. and Alber,T. (1993) A switch between two-, three-, and four-stranded coiled coils in GCN4 leucine zipper mutants. Science, 262, 1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenester E., Sasaki,T. and Timpl,R. (1999) Crystal structure of a scavenger receptor cysteine-rich domain sheds light on an ancient superfamily. Nat. Struct. Biol., 6, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer R.A., Schulthess,T., Landwehr,R., Schumacher,B., Lustig,A., Yurchenco,P.D., Ruegg,M.A., Engel,J. and Denzer,A.J. (1999) Interaction of agrin with laminin requires a coiled-coil conformation of the agrin-binding site within the laminin γ1 chain. EMBO J., 18, 6762–6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohfeldt E., Maurer,P., Vannahme,C. and Timpl,R. (1997) Properties of the extracellular calcium binding module of the proteoglycan testican. FEBS Lett., 414, 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer P. and Engel,J. (1996) Structure of laminins and their chain assembly. In Ekblom,P. and Timpl,R. (eds), The Laminins. Harwood Academic, London, UK, pp. 27–50.

- Mayr J., Lupas,A., Kellermann,J., Eckerskorn,C., Baumeister,W. and Peters,J. (1996) A hyperthermostable protease of the subtilisin family bound to the surface layer of the archaeon Staphylothermus marinus. Curr. Biol., 6, 739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan U.J. (1990) The agrin hypothesis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 55, 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patthy L. and Nikolics,K. (1993) Functions of agrin and agrin-related proteins. Trends Neurosci., 16, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokutta S., Herrenknecht,K., Kemler,R. and Engel,J. (1994) Conformational changes of the recombinant extracellular domain of E-cadherin upon calcium binding. Eur. J. Biochem., 223, 1019–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reist N.E., Magill,C. and McMahan,U.J. (1987) Agrin-like molecules at synaptic sites in normal, denervated, and damaged skeletal muscles. J. Cell Biol., 105, 2457–2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg M.A. and Bixby,J.L. (1998) Agrin orchestrates synaptic differentiation at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Trends Neurosci., 21, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda B.L., Critchlow,S.E., Begun,J., Pei,X.Y., Jackson,S.P., Blundell,T.L. and Pellegrini,L. (2001) Crystal structure of an Xrcc4–DNA ligase IV complex. Nat. Struct. Biol., 8, 1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetefeld J., Jenny,M., Schulthess,T., Landwehr,R., Schumacher,B., Frank,S., Ruegg,M.A., Engel,J. and Kammerer,R.A. (2001) The laminin-binding domain of agrin is structurally related to N-TIMP-1. Nat. Struct. Biol., 8, 705–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J.E., Glass,D.J., Yancopoulos,G.D. and Hall,Z.W. (1997) Laminin-induced acetylcholine receptor clustering: an alternative pathway. J. Cell Biol., 139, 181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R. and Brown,J.C. (1994) The laminins. Matrix Biol., 14, 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R. and Brown,J.C. (1996) Supramolecular assembly of basement membranes. BioEssays, 18, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsen G., Napier,A., Halfter,W. and Cole,G.J. (1995) Identification of a novel alternatively spliced agrin mRNA that is preferentially expressed in non-neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 15934–15937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. (1986) A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 4683–4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco P.D., Smirnov,S. and Mathus,T. (2002) Analysis of basement membrane self-assembly and cellular interactions with native and recombinant glycoproteins. Methods Cell Biol., 69, 111–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]