Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) F protein is a newly discovered HCV gene product that is expressed by translational ribosomal frameshift. Little is known about the biological properties of this protein. By performing pulse-chase labeling experiments, we demonstrate here that the F protein is a labile protein with a half-life of <10 min in Huh7 hepatoma cells and in vitro. The half-life of the F protein could be substantially increased by proteasome inhibitors, suggesting that the rapid degradation of the F protein is mediated by the proteasome pathway. Further immunofluorescence staining and subcellular fractionation experiments indicate that the F protein is primarily associated with the endoplasmic reticulum. This subcellular localization is similar to those of HCV core and NS5A proteins, raising the possibility that the F protein may participate in HCV morphogenesis or replication.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) can cause severe liver diseases, including hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. This virus belongs to the flavivirus family and has a positive-stranded RNA genome of ca. 9.6 kb. The genome of this virus contains a long open reading frame, which codes for a polyprotein with a length of slightly more than 3,000 amino acids (2). This polyprotein is cleaved by cellular and viral proteases to generate 10 viral gene products: core, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B. The core protein is the viral capsid protein with a length of 191 amino acids (p21c). It can be further cleaved to generate a smaller 179-amino-acid core protein (p19c) (15). E1 and E2 are the two viral envelope proteins. p7 contains two transmembrane domains (4), and NS2 likely contains at least four transmembrane domains (29). The functions of these two proteins are not clear. NS3 is a protease and a helicase. NS4A is a cofactor for the NS3 protease, and NS5B is the viral RNA polymerase. The functions of NS4B and NS5A are not totally clear, but they are likely involved in viral RNA replication and pathogenesis. All of these HCV proteins are believed to form replication complexes on intracellular membranes for either viral morphogenesis or RNA replication (7, 16, 23). The translation of the HCV polyprotein sequence is mediated by an internal ribosomal entry site, which comprises most of the 5′-noncoding region and the first few codons of the polyprotein coding sequence (17).

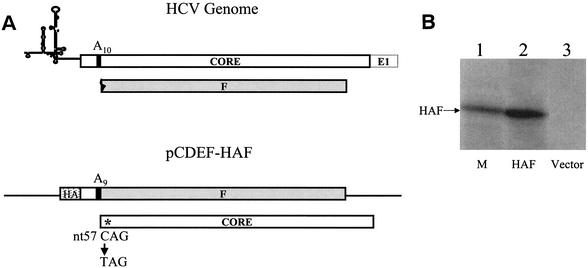

In addition to the above 10 gene products, a new HCV protein named F protein was also recently reported (24, 25, 28). This protein is apparently expressed during natural HCV infection, since its reactive antibodies were detected in HCV patients. The F protein is encoded by a reading frame that overlaps the core protein coding sequence (Fig. 1A). This F protein is expressed by a −2/+1 ribosomal frameshift during translation (24, 28). Based on the radiosequencing of the F protein synthesized in vitro, the ribosomal frameshift site for the synthesis of the F protein is located in the A-rich sequence at codons 10 to 12 of the core protein sequence (28). Thus, the F protein and the core protein have the same amino-terminal sequence. Their sequences diverge after 10 amino acids. The length of the F protein varies depending on the genotypes. For genotype 1a such as the HCV-1 isolate, the F protein is 161 amino acids long.

FIG. 1.

Expression of the HA-F protein in Huh7 hepatoma cells. (A) Illustrations of the 5′ end of the HCV-1 genome (top) and the HA-F cDNA construct (bottom). The HCV genome shown contains the 5′ noncoding region and the coding regions of the core protein and the F protein. The F protein coding sequence is shaded. A10, the stretch of 10 adenosines at codons 8 to 11 of the core protein coding sequence. This sequence contains the ribosomal frameshift signal for the synthesis of the F protein (28). The HCV-1 genome was used for the construction of the plasmid pCDEF-HAF. In this construct, one adenosine was deleted from A10 to generate A9. This deletion fused the first 10 codons of the core protein to the F protein coding sequence. The HA tag, indicated by a stippled box, was fused to the 5′ end of the coding sequence. The location of the nt 57 C-to-T mutation is indicated by an asterisk. This mutation created a TAG termination codon in the core protein sequence. (B) Immunoprecipitation of the HA-F protein. pCDEF-HAF (lane 2) or the control vector pCDEF (lane 3) was transfected into Huh7 cells by using CaPO4 precipitation procedures (13). Cells were starved for methionine for 3 h at 2 days after transfection and then radiolabeled with [35S]methionine for 1 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody (13). The [35S]methionine-labeled HA-F protein synthesized in vitro with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (28) was shown in lane 1 to serve as a marker (M).

In an attempt to understand the biological functions of the F protein, we have expressed the F protein of the HCV-1 isolate in Huh7 cells, a well-differentiated human hepatoma cell line. To facilitate the analysis, a single nucleotide was deleted from the stretch of 10 adenosines located at codons 8 to 11 (Fig. 1A). This nucleotide deletion fused the first 10 codons of the core protein to the −2/+1 reading frame. Hence, the predominant protein product produced from this sequence would be the F protein (Fig. 1A) (28). Since the HCV ribosomal frameshift signal can also mediate −1 translational frameshift (24; J. Choi, Z. Xu, and J.-H. Ou, unpublished data), which will restore the core protein translation (see below), a C-to-T mutation was also created at nucleotide (nt) 57 to generate a premature termination codon in the core protein coding sequence (Fig. 1A). This additional mutation prevented the expression of the core protein without affecting the F protein coding sequence. The antigenic epitope of hemagglutinin (HA) was fused to the amino terminus of this mutated sequence, which was then inserted into the pCDEF vector under the expression control of the promoter of the elongation factor 1α gene (28). The resulting DNA plasmid, pCDEF-HAF, was then transfected into Huh7 cells for the expression studies. The HA-tagged F protein was metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine, followed by immunoprecipitation with the anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 1B, the HA-tagged F protein could be detected in cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF but not in cells transfected with the control vector pCDEF. Similar results were obtained when HepG2 cells, a human hepatoblastoma cell line, were used for the expression studies (data not shown).

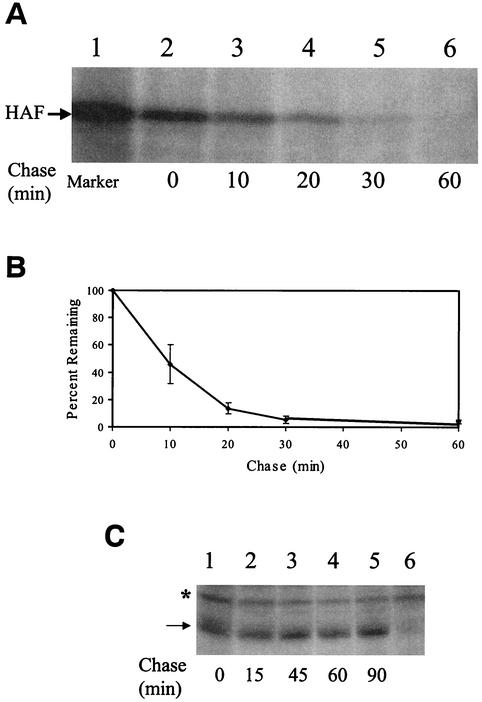

In our expression studies, we noticed that the F protein was unstable and degraded rapidly after its synthesis. For that reason, we have performed the pulse-chase labeling experiment to determine the half-life of the F protein. In this experiment, the HA-tagged F (HA-F) protein was pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min and chased with unlabeled methionine for various lengths of time. As shown in Fig. 2A, the amount of the HA-F protein decreased significantly during the chase and became undetectable after 60 min of chase. Its half-life was determined to be ca. 8 to 10 min based on densitometry (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the amount of the HA-tagged core (HA-core) protein was not apparently reduced by the chase in a similar pulse-chase labeling experiment (Fig. 2C), a finding in agreement with a previous report that the core protein is a stable protein unless it is truncated (22).

FIG. 2.

Pulse-chase labeling experiment of the HCV proteins expressed in Huh7 cells. (A) Pulse-chase labeling experiment of the HA-F protein. Huh7 cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF by CaPO4 precipitation were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min and chased with unlabeled methionine for 0, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min (lanes 2 to 6). Cells were then lysed for immunoprecipitation with the anti-HA antibody by our previous procedures (14). Lane 1 is the [35S]methionine-labeled HA-F protein marker, which was synthesized in vitro by using the rabbit reticulocyte lysates. (B) Determination of the half-life of the HA-F protein. The autoradiogram shown in panel A was analyzed with SigmaScan. The results represented the average of three independent experiments. The HA-F protein level at the zero time point of chase was defined as 100%. (C) Pulse-chase labeling experiment of the HA-core protein. Huh7 cells transfected with pCDEF-HA-core (13) were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min and chased with unlabeled methionine for 0, 15, 45, 60, and 90 min (lanes 1 to 5). Lane 6 was Huh7 cells transfected with the control pCDEF vector. The asterisk marks the location of a nonspecific protein band. The arrow denotes the core protein band.

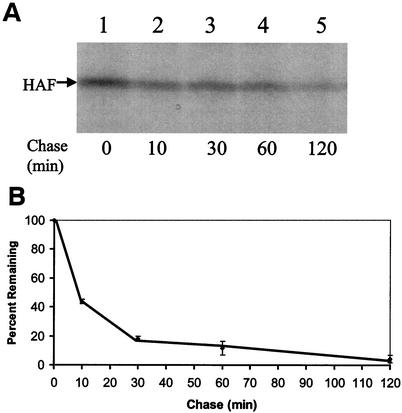

The results shown in Fig. 2 demonstrate that the HA-F protein is a labile protein in Huh7 cells. To determine whether the HA-F protein synthesized in vitro is similarly unstable, HA-F protein was synthesized in vitro by using rabbit reticulocyte lysates and then pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min. After the translation reaction was stopped with cycloheximide, the F protein was chased for various lengths of time. As shown in Fig. 3A, the amount of HA-F protein was reduced significantly during the chase; these findings are similar to the results observed in Huh7 cells. The half-life was determined to be slightly less than 10 min based on densitometry readings (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained when the F protein was expressed in vitro without the HA tag (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Pulse-chase labeling experiments of the HA-F protein synthesized in vitro. (A) Autoradiograms of the pulse-chase experiments. The HA-F coding sequence was inserted into pRc/CMV (Invitrogen). The HA-F RNA was then synthesized by using the T7 RNA polymerase and translated with the rabbit reticulocyte lysates. Details of these experimental procedures had been described (28). The HA-F protein was pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min. The translation reaction was then stopped by the addition of cycloheximide to a final concentration of 400 μM. The HA-F protein was then chased for 0, 10, 30, 60, or 120 min (lanes 1 to 5). (B) Half-life of the HA-F protein in vitro. The results shown in panel A were quantified with SigmaScan. The results represented the average of three independent experiments. The HA-F protein level at the zero time point was defined as 100%.

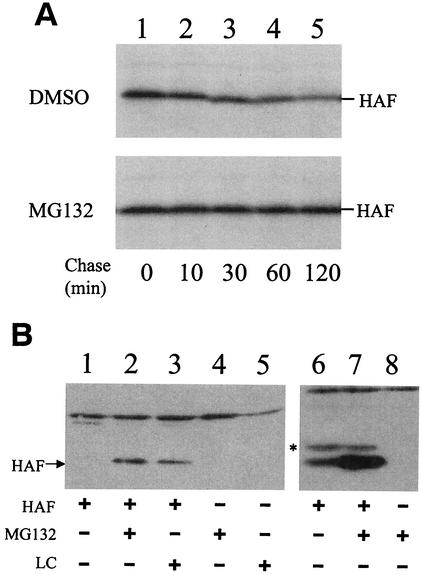

To understand the molecular mechanism that is responsible for the instability of the F protein, serine protease inhibitors, including leupeptin, aprotinin, and Pefabloc, were added into the translation mixture at the beginning of the chase in separate pulse-chase labeling experiments. None of these protease inhibitors could increase the half-life of the F protein (data not shown). In contrast, if the proteasome inhibitor MG132 was added into the translation mixture at the beginning of the chase, the decrease of the HA-F protein signal was unapparent during the 2-h chase period (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that the degradation of the F protein was most likely mediated by the proteasome pathway in vitro. To determine whether the HA-F protein was also degraded by the same pathway in Huh7 cells, cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF were treated with MG132 or the control solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 6 h, lysed, and then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 4B, the expression level of the HA-F protein was low in DMSO-treated cells (lanes 1 and 6). However, this expression level was substantially increased if cells were treated with MG132 (lanes 2 and 7). Similar results were obtained when Huh7 cells were treated with lactacystin, another proteasome inhibitor (lane 3). These results indicated that the F protein was likely also degraded by the proteosome pathway in Huh7 cells. Note that in lanes 6 and 7 the cells were transfected with an expression plasmid identical to pCDEF-HAF except that nt 57 was not mutated from C to T, which would create a premature termination codon in the core protein coding sequence (Fig. 1A). In this case, the HA-tagged core protein was also detected. This result is consistent with the recent findings that the HCV ribosomal frameshift signal could also mediate the −1 ribosomal frameshift to express the core protein from the HAF sequence (24; Choi et al., unpublished).

FIG. 4.

Stabilization of the HA-F protein by proteasome inhibitors. (A) Pulse-chase labeling experiments of HA-F synthesized in vitro. The HA-F protein was pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine for 10 min as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The translation reactions were then stopped with cycloheximide. MG132 (lower panel) or its control solvent DMSO (upper panel) was then added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The reaction mixtures were chased for 0, 10, 30, 60, or 120 min (lanes 1 to 5). (B) Stabilization of HA-F by proteasome inhibitors in Huh7 cells. pCDEF-HAF (lanes 1 to 3), its control vector pCDEF (lanes 4, 5, and 8), or pCDEF-9aCore (lanes 6 and 7) was transfected into Huh7 cells. pCDEF-9aCore is identical to pCDEF-HAF with the exception that it does not have the C-to-T mutation at nt 57 (28). At 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with DMSO (lane 1), 1 μg of MG132/ml (lanes 2 and 4), or 20 μM of lactacystin (LC) (lanes 3 and 5) for 6 h. Cells were then lysed for Western blot analysis with the anti-HA antibody by using our previous procedures (13). The protein signals were analyzed by the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). The expression level of HAF was low in DMSO-treated cells. Hence, lanes 6 to 8 were purposely overexposed on the film to reveal the HAF protein in DMSO-treated cells (lane 6). The asterisk marks the location of the HA-core protein. The identity of this protein was confirmed by Western blotting with the anti-core antibody (data not shown).

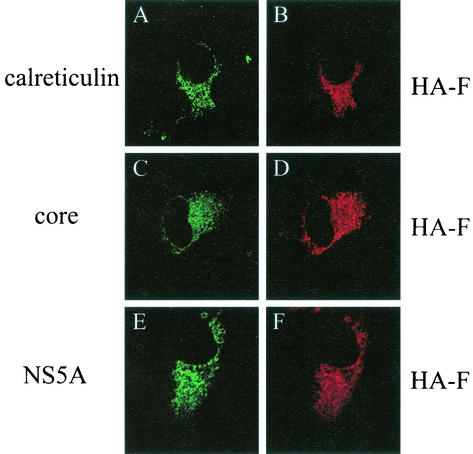

To investigate the possible biological functions of the F protein, we have also analyzed its subcellular localization. Huh7 cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with the anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 5, the HA-F protein displayed a punctate and perinuclear staining pattern similar to that of calreticulin, a protein associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This subcellular localization was also similar to that of the core protein in a cotransfection experiment. Stable Huh7 cells that contain bicistronic HCV RNA replicons that contained the neomycin gene and the HCV NS3-NS5 sequence had been produced by several laboratories (1, 8, 9, 11). We had also established stable Huh7 cells containing the HCV replicon (unpublished data). The HA-F protein expressed in these Huh7 cells by transient transfection also displayed a subcellular localization similar to that of NS5A (Fig. 5). Both core and NS5A proteins had previously been shown to localize predominantly to the ER membranes (3, 10, 15, 19, 20). Although the subcellular localization of the HA-F protein was similar to those of core and NS5A, coimmunoprecipitation experiments failed to demonstrate a direct physical interaction between HA-F and the core protein or NS5A (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunofluorescence double-staining analysis for the subcellular localization of the HA-F protein. (A and B) Huh7 cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF were double stained with rabbit anti-calreticulin and mouse anti-HA primary antibodies and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and rhodamine (RITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. (C and D) Huh7 cells cotransfected with pCDEF-HAF and pCDEF-core (13) were double stained with rabbit anti-HCV core and mouse anti-HA primary antibodies and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and RITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. (E and F) Huh7 cells containing the HCV subgenomic RNA replicon (unpublished data) were transfected with pCDEF-HAF and double stained with mouse anti-NS5A and rat anti-HA primary antibodies and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse and RITC-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibodies. In all cases, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 48 h after transfection for staining by using our previous procedures (14). The HA-F protein was stained in red, whereas all of the other proteins were stained in green. The images were captured with a Nikon confocal microscope at the USC Liver Center.

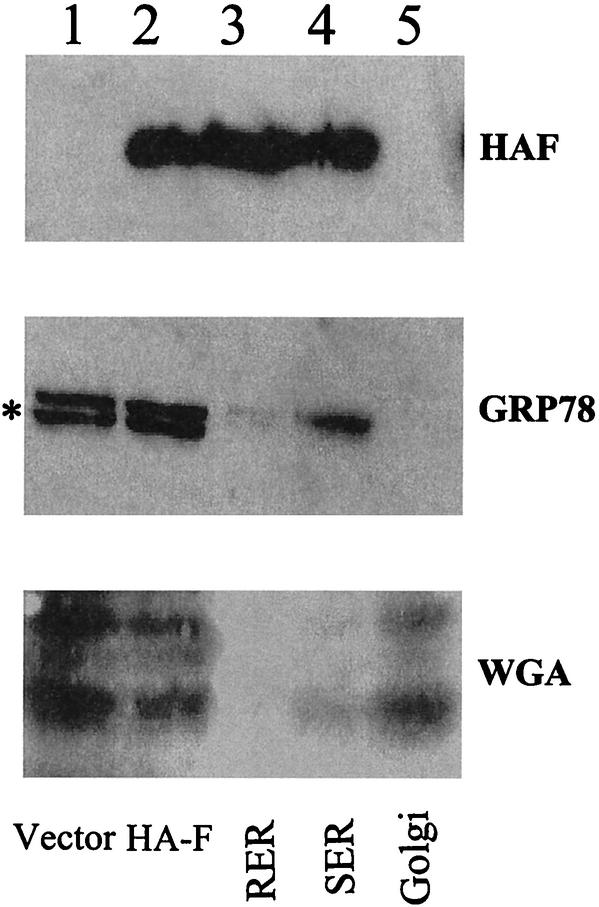

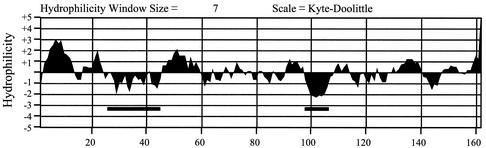

The ER association of the HA-F protein was further supported by the membrane fractionation experiments by using a discontinuous gradient containing 2.0, 1.3, 1.0, and 0.6 M sucrose solutions. The rough ER, the smooth ER, and the Golgi membranes were enriched in the 2.0-1.3, 1.3-1.0, and 1.0-0.6 M interfaces, respectively, in this sucrose gradient (26). To increase the sensitivity of the Western blot analysis, Huh7 cells were treated with MG132 for 6 h to stabilize the HA-F protein. As shown in Fig. 6, the HA-F protein was detected in both the rough ER and the smooth ER fractions but not the Golgi fraction. To ensure that this gradient indeed faithfully separated ER and Golgi membranes, individual fractions were also analyzed by Western blotting with the anti-GRP78 antibody and wheat germ agglutinin. GRP78 is an ER-associated protein, and wheat germ agglutinin binds specifically to trans-Golgi proteins containing clustered terminal N-acetylneuraminic acid residues, as well as N-acetylglucosamine-containing oligosaccharide chains (26). Calreticulin was not analyzed in these studies due to the lack of a good reactive antibody for Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 6, GRP78 was detected mostly in the ER fractions, and proteins with complex-type glycans were detected primarily in the Golgi fraction, indicating that ER and Golgi membranes were faithfully separated in our gradient fractionation procedures. Thus, the results shown in Fig. 6 were in support of the immunofluorescence staining results and indicated that the HA-F protein was primarily an ER-associated protein. The hydrophobicity analysis of the F protein sequence revealed two major hydrophobic domains located at amino acids 28 to 45 and amino acids 95 to 110 (Fig. 7). Either one or both of these two domains may serve as the domains for the F protein to become associated with the ER membranes. Although the length of the HCV F protein varies depending on the genotypes, most of them are longer than 126 amino acids and thus contain these two hydrophobic domains.

FIG. 6.

Membrane fractionation experiments for the analysis of the subcellular localization of HA-F. Huh7 cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF were rinsed with PBS and scraped off the plates into PBS. After a brief centrifugation at 1,500 × g, cells were homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer in a 0.25 M sucrose solution containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After a brief centrifugation at 15,000 × g, the postnuclear supernatant was loaded on a discontinuous sucrose gradient containing 0.6, 1.0, 1.3, and 2.0 M sucrose in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The gradient was centrifuged at 40,000 rpm by using a Beckman SW40 Ti rotor for 2 h at 4°C as previously described (26). Lane 1, cells transfected with the control vector pCDEF; lanes 2 to 5, cells transfected with pCDEF-HAF; lanes 1 and 2, the postnuclear supernatant prior to fractionation; lane 3, the rough ER (RER) fraction isolated from the 1.3-2.0 M sucrose interface; lane 4, the smooth ER (SER) fraction isolated from the 1.0-1.3 M sucrose interface; lane 5, the Golgi fraction isolated from the 0.6-1.0 M sucrose interface. (Top panel) Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody; (middle panel) Western blot analysis with anti-GRP78 antibody; (bottom panel) Western blot analysis with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA). The asterisk denotes a nonspecific protein band. This protein band did not cofractionate with GRP78 into the ER membrane fractions. Wheat germ agglutinin reacted with multiple protein bands.

FIG. 7.

Hydrophilicity plot of the F protein. The HCV-1 F protein coding sequence with 1 nt deletion in the 10-A stretch was analyzed by the MacVector program. The two thick lines highlight the two major hydrophobic domains.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here that the HCV F protein is a short-lived, ER-associated protein. This protein is synthesized by ribosomal frameshift, which occurs at a frequency of ca. 2% in Huh7 cells (28; Choi et al., unpublished). Hence, the finding that this protein is labile with a half-life of <10 min is interesting. It is conceivable that the F protein is needed in only a very small amount in the HCV life cycle. Suzuki et al. recently reported a p17 protein that could be expressed from a genotype 1b HCV core protein coding sequence (22). This protein, which could be detected in their Western blot analysis only when cells were treated with MG132, was thought to be a truncated core protein. Based on our studies, one must carefully reexamine whether the the p17 protein detected by these authors was actually the F protein.

It is not unprecedented for an underproduced viral protein to be also a labile protein. The Sindbis virus nsP4 polymerase is expressed by readthrough of an opal codon, followed by proteolytic cleavage, and thus is underproduced compared to other nonstructural proteins (12). This protein is also short-lived and degraded rapidly by the ubiquitin-proteasome N-end rule pathway (6). It has been suggested that the instability of nsP4 may be important for the cessation of minus-strand RNA synthesis during viral replication (6, 21).

The replication of HCV occurs on the membrane structures in the cells, and all of the HCV proteins derived from the polyprotein have been found to associate with the ER membranes either directly or indirectly (4, 5, 7, 15, 18, 27, 29). The finding that the HCV F protein is associated with ER membranes with a subcellular localization similar to those of the HCV core protein and NS5A raises the possibility that the F protein may also be a component of the HCV replication complex. The F protein does not appear to bind directly to the core protein and NS5A. Thus, if it is indeed a component of the HCV replication complex, it will likely interact with this complex through other HCV proteins or indirectly through cellular proteins. The F protein is not needed for HCV RNA replication, because its absence did not impede the replication of the HCV subgenomic RNA replicons (1, 8, 9, 11). However, it remains to be determined whether the F protein may regulate HCV RNA replication or participate in viral morphogenesis. Our finding that the F protein is a short-lived, ER-associated protein will now allow us to further explore its biological functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Mac Veigh at the USC Liver Center for help with the confocal microscopy.

This work was supported by an American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship (PF-01-037-01-MBC) to J.C. and by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (to J.O.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Blight, K. J., A. A. Kolykhalov, and C. M. Rice. 2000. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 290:1972-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blight, K. J., A. Grakoui, H. L. Hanson, and C. M. Rice. 2002. The molecular biology of hepatitis C virus, p. 81-108. In J.-H. J. Ou (ed.), Hepatitis viruses. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, Mass.

- 3.Brass, V., E. Bieck, R. Montserret, B. Wolk, J. A. Hellings, H. E. Blum, F. Penin, and D. Moradpour. 2002. An amino-terminal amphipathic alpha-helix mediates membrane association of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8130-8139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrere-Kremer, S., C. Montpellier-Pala, L. Cocquerel, C. Wychowski, F. Penin, and J. Dubuisson. 2002. Subcellular localization and topology of the p7 polypeptide of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 76:3720-3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cocquerel, L., A. Op de Beeck, M. Lambot, J. Roussel, D. Delgrange, A. Pillez, C. Wychowski, F. Penin, and J. Dubuisson. 2002. Topological changes in the transmembrane domains of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. EMBO J. 21:2893-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Groot, R. J., T. Rumenapf, R. J. Kuhn, E. G. Strauss, and J. H. Strauss. 1991. Sindbis virus RNA polymerase is degraded by the N-end rule pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8967-8971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger, D., B. Wolk, R. Gosert, L. Bianchi, H. E. Blum, D. Moradpour, and K. Bienz. 2002. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J. Virol. 76:5974-5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo, J. T., V. V. Bichko, and C. Seeger. 2001. Effect of alpha interferon on the hepatitis C virus replicon. J. Virol. 75:8516-8523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda, M., M. Yi, K. Li, and S. M. Lemon. 2002. Selectable subgenomic and genome-length dicistronic RNAs derived from an infectious molecular clone of the HCV-N strain of hepatitis C virus replicate efficiently in cultured Huh7 cells. J. Virol. 76:2997-3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanford, R. E., L. Notvall, D. Chavez, R. White, G. Frenzel, C. Simonsen, and J. Kim. 1993. Analysis of hepatitis C virus capsid, E1, and E2/NS1 proteins expressed in insect cells. Virology 197:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohmann, V., F. Korner, J. Koch, U. Herian, L. Theilmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez, S., J. R. Bell, E. G. Strauss, and J. H. Strauss. 1985. The nonstructural proteins of Sindbis virus as studied with an antibody specific for the C terminus of the nonstructural readthrough polyprotein. Virology 141:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu, W., A. Strohecker, and J. H. Ou. 2001. Post-translational modification of the hepatitis C virus core protein by tissue transglutaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47993-47999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu, W., and J.-H. Ou. 2003. Phosphorylation of hepatitis C virus core protein by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Virology 300:20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLauchlan, J., M. K. Lemberg, G. Hope, and B. Martoglio. 2002. Intramembrane proteolysis promotes trafficking of hepatitis C virus core protein to lipid droplets. EMBO J. 21:3980-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mottola, G., G. Cardinali, A. Ceccacci, C. Trozzi, L. Bartholomew, M. R. Torrisi, E. Pedrazzini, S. Bonatti, and G. Migliaccio. 2002. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural proteins are localized in a modified endoplasmic reticulum of cells expressing viral subgenomic replicons. Virology 293:31-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rijnbrand, R. C., and S. M. Lemon. 2000. Internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation in hepatitis C virus replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 242:85-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt-Mende, J., E. Bieck, T. Hugle, F. Penin, C. M. Rice, H. E. Blum, and D. Moradpour. 2001. Determinants for membrane association of the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44052-44063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selby, M. J., Q. L. Choo, K. Berger, G. Kuo, E. Glazer, M. Eckart, C. Lee, D. Chien, C. Kuo, and M. Houghton. 1993. Expression, identification and subcellular localization of the proteins encoded by the hepatitis C viral genome. J. Gen. Virol. 74:1103-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi, S. T., S. J. Polyak, H. Tu, D. R. Taylor, D. R. Gretch, and M. M. Lai. 2002. Hepatitis C virus NS5A colocalizes with the core protein on lipid droplets and interacts with apolipoproteins. Virology 292:198-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirako, Y., and J. H. Strauss. 1994. Regulation of Sindbis virus RNA replication: uncleaved P123 and nsP4 function in minus-strand RNA synthesis, whereas cleaved products from P123 are required for efficient plus-strand RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 68:1874-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki, R., K. Tamura, J. Li, K. Ishii, Y. Matsuura, T. Miyamura, and T. Suzuki. 2001. Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of hepatitis C virus core protein is regulated by processing at its carboxyl terminus. Virology 280:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu, H., L. Gao, S. T. Shi, D. R. Taylor, T. Yang, A. K. Mircheff, Y. Wen, A. E. Gorbalenya, S. B. Hwang, and M. M. Lai. 1999. Hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase and NS5A complex with a SNARE-like protein. Virology 263:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varaklioti, A., N. Vassilaki, U. Georgopoulou, and P. Mavromara. 2002. Alternate translation occurs within the core coding region of the hepatitis C viral genome. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17713-17721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walewski, J. L., T. R. Keller, D. D. Stump, and A. D. Branch. 2001. Evidence for a new hepatitis C virus antigen encoded in an overlapping reading frame. RNA 7:710-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, J., A. S. Lee, and J. H. Ou. 1991. Proteolytic conversion of hepatitis B virus e antigen precursor to end product occurs in a postendoplasmic reticulum compartment. J. Virol. 65:5080-5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolk, B., D. Sansonno, H. G. Krausslich, F. Dammacco, C. M. Rice, H. E. Blum, and D. Moradpour. 2000. Subcellular localization, stability, and trans-cleavage competence of the hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A complex expressed in tetracycline-regulated cell lines. J. Virol. 74:2293-2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, Z., J. Choi, T. S. Yen, W. Lu, A. Strohecker, S. Govindarajan, D. Chien, M. J. Selby, and J. Ou. 2001. Synthesis of a novel hepatitis C virus protein by ribosomal frameshift. EMBO J. 20:3840-3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaga, A. K., and J. H. Ou. 2002. Membrane topology of the hepatitis C virus NS2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33228-33234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]