Abstract

The chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are required for HIV-1 to enter cells, and the progression of HIV-1 infection to AIDS involves a switch in the co-receptor usage of the virus from CCR5 to CXCR4. These receptors therefore make attractive candidates for therapeutic intervention, and we have investigated the silencing of their genes by using ribozymes and single-stranded antisense RNAs. In the present study, we demonstrate using ribozymes that a depletion of CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNAs can be achieved simultaneously in human PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells), cells commonly used by the virus for infection and replication. Ribozyme activity leads to an inhibition of the cell-surface expression of both CCR5 and CXCR4, resulting in a significant inhibition of HIV-1 replication when PBMCs are challenged with the virus. In addition, we show that small single-stranded antisense RNAs can also be used to silence CCR5 and CXCR4 genes when delivered to PBMCs. This silencing is caused by selective degradation of receptor mRNAs.

Keywords: antisense RNA, chemokine receptor, gene silencing, hammerhead ribozyme, HIV, ribozyme

Abbreviations: CCR5, CC chemokine receptor 5; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CXCR4, CXC chemokine receptor 4; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; gp, glycoprotein; IL-2, interleukin-2; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; miRNA, micro RNA; M-tropic, macrophage-tropic; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RNAi, RNA interference; siRNA, small interfering RNA; RT, reverse transcription; T-tropic, T-cell-tropic; V3 loop, variable loop 3

INTRODUCTION

Hiv-1 entry into human CD4 cells requires the expression of chemokine receptors such as CXCR4 and CCR5 [1]. It is thought that the binding site for the co-receptors is on the V3 loop (variable loop 3) of gp120 (glycoprotein 120), which is exposed following massive conformational changes after the virus binds to the CD4 receptor on the membrane of the target cells [2,3]. As a result of the differential usage of these receptors by the virus, HIV-1 strains are described as M-tropic (macrophage-tropic) if CCR5 is involved, T-tropic (T-cell-tropic) if CXCR4 is involved and dual tropic if both receptors are involved. CCR5 is largely used by the virus in the initial stages of infection and T-tropic strains arise as a result of mutations in the V3 loop of gp120, which occurs in the late stages of infection [4].

Following the discovery that mutations in CCR5, which prevent expression of the receptor molecule, confer resistance to M-tropic strains of the virus [5], there has been intense interest in finding ways of exploiting this. Individuals who are homozygous for a deletion in the CCR5 gene, which results in a truncated form of the receptor [6], apparently suffer no ill effects, and, based around this discovery, there has been a series of approaches aimed at removing this viral target from the cell [7–11].

It can be argued, however, that targeting only CCR5 may not be beneficial as a clinical approach because of the virus's ability to modify its co-receptor usage [12]. Moreover, inhibition of only CCR5 may risk generating new virus strains and accelerating disease progression [13]. There are therefore good reasons to target CXCR4 as well if a long-term approach is to be effected, and some advances into this area have been made [14]. In view of these aspects, we have developed strategies for silencing the genes of both CCR5 and CXCR4 by using ribozymes and antisense RNA.

Gene silencing using siRNAs (small interfering RNAs) has recently received widespread attention as a method for disrupting gene function, a process commonly referred to as RNAi (RNA interference) [15]. RNAi has its evolutionary origin in the response that cells make to foreign RNA, such as that coming from viruses, and to unwanted gene activity, such as that generated by transposons [15–17]. In reaction to these activities, which are generally believed to result in the formation of dsRNA (double-stranded RNA), eukaryotic cells perform a multistep process generating siRNAs 21–23 nt long. siRNAs are used by the cell to direct the sequence-specific degradation of a target RNA molecule. It has also been found that dsRNA, of approx. 21 nt, synthesized in vitro, can act as siRNAs to silence genes from mammalian cells [18]. Single-stranded miRNA (microRNA) is produced by a similar mechanism to that used for making siRNA [19], but it functions by translational inhibition of the target RNA, rather than causing its destruction. The degree of complementarity between the miRNA and its target determines how it functions [20]. Exact complementarity is required for degradation of the target, whereas base mismatches lead to a pathway resulting in translational blockage.

We have investigated the effectiveness of targeting ribozymes and single-stranded antisense RNA to the mRNAs of both CCR5 and CXCR4 with the idea of using them in the transient transfection of human PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells), the natural host cells of HIV. For each receptor mRNA, the ribozyme or antisense molecule was designed to target the same sequence of the mRNA, so that a comparison could be made between the activities of the two types of molecule. First, we show that ribozymes are effective in cleaving the mRNAs for CCR5 and CXCR4 simultaneously, leading to a reduction in cell-surface expression of both receptors in PBMCs, and that this in turn results in a significant inhibition of HIV-1 replication in these cells. Secondly, we show that small single-stranded antisense RNAs, having approx. 50% complementarity to their target, are also effective in degrading the mRNAs of CCR5 and CXCR4 in human PBMCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of DNA cassettes used for producing ribozyme and antisense molecules

Each cassette was synthesized as a set of partially complementary oligodeoxyribonucleotides, which were annealed and extended using Taq polymerase. Restriction sites were incorporated in each cassette as shown, and were used for cloning into pUC19. In addition, the CCR5 cassette was cloned separately into pUC19, producing pCCR5Rz, in order to study it independently. The CXCR4 ribozyme cassette was cloned into pCCR5Rz using the PstI and BamHI sites, thus placing the CXCR4 cassette upstream of the CCR5 ribozyme cassette generating pCXCR4/CCR5Rz.

Supplementary Table 1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/394/bj3940511add.htm) shows the sequences of the CXCR4 ribozyme cassette used to produce pCXCR4Rz and pCXCR4/CCR5Rz, the CCR5 ribozyme cassette used to produce pCCR5Rz, the CXCR4 antisense cassette used to produce pCXCR4As and the CCR5 antisense cassette used to produce pCCR5As.

Ribozyme self-cleavage and cleavage of CCR5 and CXCR4 mRNAs

pCCR5Rz (10 μg) was linearized with SacI, and a 93-base transcript was generated using T7 polymerase and RiboMAX™ buffer (Promega) with 24 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 1 h. Self-cleavage and target cleavage was studied in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2. The CCR5 antisense transcript was synthesized from pCCR5As and self-cleavage products were produced under the same conditions.

pCXCR4/CCR5Rz was linearized using XbaI and EcoRI to remove the CCR5 ribozyme DNA cassette, which was then purified by agarose gel electro-elution. The linearized plasmid was used as a template to generate the CXCR4 ribozyme transcript using T7 RNA polymerase and RiboMAX™ buffer. The CXCR4 ribozyme was incubated with 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 4 h to obtain the self-cleaved products. The CXCR4 antisense molecule was generated using T7 RNA polymerase and XbaI-linearized pCXCR4As, and it was incubated with 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C for 4 h to obtain the self-cleaved products.

To produce a source of CCR5 mRNA, RT (reverse transcription)–PCR was performed on mRNA from PBMCs using the forward primer, 5′-TGCACAGGGTGGAACAAGATGG-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-CACTTGATGCCGGTTCACAAGC-3′. The PCR product was then cloned into pcDNA3 that had been cut with EcoRV and the site was ‘T’-ed with dTTP and Taq polymerase [21]. CCR5 mRNA was produced with T7 RNA polymerase after linearizing the plasmid with XbaI. The CXCR4 mRNA was produced using a similar method. In this case the forward primer was 5′-CATGGAGGGGATCAGTATATAC-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-ACATCTGTGTTAGTCGGAGGT-3′. The PCR product was cloned into pcDNA3 at a ‘T’-ed EcoRV site. The CXCR4 transcript was produced by T7 RNA polymerase from the XbaI-linearized template.

Construction and testing of pCS2 and pZEQ

Two plasmids were made, both of which could generate T7 RNA polymerase: pCS2P and pZEQ. Plasmid pCS2P was derived from pCS2NLS, a mammalian expression vector containing a CMV (cytomegalovirus) promoter, an NLS (nuclear localization sequence) and a SV40 (simian virus 40) polyadenylation sequence [22]. The T7 RNA polymerase gene was amplified using PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) from pT7Auto-2 [23] using a forward primer with an EcoRI site (single underlined) and an NcoI site (double underlined), 5′-ACGAATT-CCATGGACACGATTAACATC-3′, and a reverse primer with a BamHI site (underlined), 5′-ATATAAGGATCCTTACGCGAAGCGAAG-3′. The forward primer introduced a codon change from AAC to GAC in the second codon, resulting in an amino acid change from asparagine to aspartic acid in the T7 polymerase. This has been shown not to affect the activity of the polymerase [24]. The PCR product was cloned into the EcoRI and SnaBI sites of pCS2NLS. The NLS was not necessary for our purpose and was subsequently removed by digestion with NcoI, and the vector was recircularized. The plasmid pZEQ was derived from pET11(a) (Novagen), and was designed to produce an autogene system for making T7 RNA polymerase autocatalytically in the cytoplasm. An IRES (internal ribosomal entry site), derived from the 5′-untranslated region of the encephalomyocarditis virus, was obtained from pTM1 [25] by PCR with forward primer, 5′-GCTCTAGACCACAACGGTTTCCCTCTAG-3′, containing an XbaI site (underlined) and reverse primer, 5′-CAGCTTCCTTTCGGGCTTTGTTAGCAGC-3′. This was cloned into the XbaI and BamHI sites of pET11(a) to produce pET11EMC. To form the autogene, the T7 RNA polymerase fragment, produced previously using PCR with NcoI site and BamHI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends respectively, was then introduced into the corresponding sites of pET11EMC, forming pZEQ.

Culturing PBMCs and transfection

PBMCs were isolated from buffy coats, which were obtained from a blood bank (National Blood Service, London, U.K.). The cells were rested overnight in culture medium containing RPMI 1640 with 10% (v/v) foetal calf serum (Invitrogen) before transfection using DMRIE-C (1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-3-dimethylhydroxyethyl ammonium bromide and cholesterol) reagent (Invitrogen). The efficiency was close to 100% when used with a β-galactosidase reporter gene.

RT–PCR detection of CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNA levels in PBMCs transfected with ribozyme-generating plasmids

Single donor PBMC samples were isolated from healthy individuals by the National Blood Service, and only samples with a wild-type CCR5 genotype [26] were used. For each experiment, the following transfections were performed: an untransfected control, a pCS2P control, pCS2P+pZEQ control, pCS2P+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz and pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz. Experiments with CXCR4 and CCR5 antisense RNAs were performed in the same way. After 2 days in culture, RNA was isolated from these samples, and CCR5 and CXCR4 mRNA levels were assessed using RT–PCR using CXCR4-, CCR5- and β-actin-specific primers. Quantification of receptor mRNA levels was performed using densitometry of the gels using Gel Doc 1000 (Bio-Rad) using β-actin as an internal control.

Receptor detection and quantification

Flow cytometry was used for the assessment of cell-surface expression. Fluorescent conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CXCR4 and CCR5 (BD Bioscience) were used to stain PBMCs which were transfected with vectors pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz. Detection of CXCR4 and CCR5 were carried out by direct single-colour staining in order to avoid any possible interference caused by secondary or double staining. A FACS (FACScan, BD Bioscience) was used to collect and analyse the data. PBMCs were first transfected with the relevant vectors, then immediately stimulated with 1 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin-L (Sigma) and human IL-2 (interleukin-2) at 10 units/ml in culture medium and incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. IL-2 was added at 10 units/ml every 3 days. Staining of PBMCs with antibodies was carried out at 3, 5, 7, 10 and 12 days after stimulation. Phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody, 12Q5, and FITC-conjugated anti-CCR5 monoclonal antibody, 2D7 (both from BD Bioscience), were used. The staining protocol and FACS analysis followed standard procedures from the manufacturer.

Infection of PBMCs with HIV-1 and detection of HIV-1 p24 molecule

Controls and ribozyme-treated samples were as described above. At day 5 after transfection, cells were washed three times in culture medium and were counted using Trypan Blue exclusion. Live cells (2×106) were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2 with HIV-1 strains LAI or SF162 and their p24 concentrations at 3×103 pg/ml. Cells were then washed three times, as mentioned above, and were resuspended in 5 ml of the culture medium before continuation of culturing at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator with 10 units/ml IL-2. Fresh IL-2 was added at the same concentration on day 3 post-infection. On day 7 after infection, the cells were harvested, and the supernatants were retained for the detection of the HIV-1 p24 molecule. An ELISA-based kit, HIV p24 Antigen Assay (Coulter Immunotech), was used for the detection according to the manufacturer's instructions. HIV-1 strains LAI and SF162 were obtained from the AIDS Reagent Project, Medical Research Council, Potters Bar, Herts., U.K.

RESULTS

Ribozyme and single-stranded antisense RNA construction

Ribozymes of the hammerhead type were designed to bind to various sites on the mRNAs for CXCR4 and CCR5, and were assessed in terms of their folding and free energy levels using Mfold and FoldRNA software (Accelrys GCG) [27,28]. The site on CXCR4 selected for ribozyme action was the 14th GUC, with the target covering 13 bases. Two sets of six base pairs formed stems I and III (Figure 1A). For CCR5, the second GUC in the sequence was selected. Again the ribozyme was designed to cover a target site of 13 bases, but with seven base pairs forming stem I, and five base pairs forming stem III (Figure 1B). Single-stranded antisense RNAs lacking the catalytic regions, characteristic of ribozymes, were constructed to CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNAs using similar principles; they were designed so that they bound to the same target site of 13 bases as that covered by the ribozymes, and diagrams of the molecules binding to their respective targets are shown in Figures 1(C) and 1(D).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of CXCR4 and CCR5 ribozymes and antisense molecules binding to their respective targets.

(A) Computer-generated structure of the CXCR4 ribozyme binding to its target mRNA. (B) Computer-generated structure of the CCR5 ribozyme binding to its target mRNA. (C) Computer-predicted structure of the CXCR4 antisense molecule binding to its target site. (D) Computer-predicted structure of the CCR5 antisense molecule binding to its target site. In each case, the ribozyme or antisense molecule is drawn as a thick line with the target as a thin line. The target for CXCR4 is from position 609 to 621 in the sequence (GenBank® accession number M99293) and that for CCR5 is from position 256 to 268 (GenBank® accession number X91492).

The design of the ribozyme DNA cassettes and their method of construction are shown in Figures 2(A) and 2(B), and are explained in the Materials and methods section and the accompanying Figure legend. The ribozymes against the CCR5 and CXCR4 mRNAs (trans-acting ribozymes) were designed to be produced from a T7 promoter. The transcript from this region of the cassette has a stem–loop at the 5′ end, and is terminated by a cis-acting ribozyme. The stem–loop was included to increase the overall stability in a cellular environment, and the cis-acting ribozyme ensured that the trans-acting ribozyme was generated in the form of a stable well-defined molecular species [29]. In the case of the antisense molecules, a stability loop was also introduced at the 5′ end of the molecule, and a cis-acting ribozyme was combined at the 3′ end; the activity of the cis-acting ribozyme resulted in an antisense molecule of defined length, having a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate end. The antisense molecules were designed so that they could be produced from a T7 promoter, as was the case for the ribozymes, and details of the DNA cassettes and the associated transcripts are shown in Figures 2(C) and 2(D).

Figure 2. DNA cassettes used for producing ribozyme and antisense molecules.

The arrangement of each cassette is shown, and below is a model of the corresponding transcript formed. In each model, the self-cleaving cis-acting hammerhead ribozyme is drawn as a thin line, and the thick line represents the trans-acting hammerhead molecule. The conformation of the active species produced after self-cleaving is indicated on the right of each Figure. (A) CXCR4 ribozyme cassette. (B) CCR5 ribozyme cassette. (C) CXCR4 antisense cassette. (D) CCR5 antisense cassette.

Self-cleaving activity of the cis-acting ribozymes

Generation of the complete transcripts for producing the CCR5 and CXCR4 trans-acting ribozymes showed that self-cleavage by the cis-acting ribozymes occurred in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 (Figure 3A, lanes a, b, e and f). Under similar conditions, the cis-acting ribozymes that associated with the CCR5 and CXCR4 antisense-generating transcripts were also active (Figure 3A, lanes c, d, g and h).

Figure 3. Ribozyme in vitro activity and specificity assay.

Values on the left of the Figures represent size markers as number of bases. (A) Self-cleavage for ribozyme and antisense molecules. Lane a (control) shows the complete CCR5 ribozyme-generating transcript (93 bases) after incubation for 4 h in the absence of Mg2+ ions. Lane b shows a similar transcript in the presence of Mg2+ ions demonstrating cleavage and producing a 45 base cis-acting ribozyme and a 48 base trans-acting ribozyme that are indistinguishable in size on this gel. Lane c shows the complete CCR5 antisense-generating transcript (73 bases), after incubating in the absence of Mg2+ ions. Lane d shows a similar transcript after incubating with Mg2+ ions where it is self-cleaved into two fragments: a 27 base trans-acting molecule and a 46 base cis-acting ribozyme. Lane e shows the complete CXCR4 ribozyme-generating transcript (99 bases) after incubating in the absence of Mg2+ ions. Lane f shows a similar transcript in the presence of Mg2+, where it is self-cleaved into trans-acting (50 bases) and cis-acting (49 bases) products. Lane g shows the complete CXCR4 antisense-generating transcript (79 bases) in the absence of Mg+2. Lane h shows a similar transcript in the presence of Mg2+, where it self-cleaved to generate two RNA fragments: one of 29 bases, the CXCR4 trans-acting antisense molecule, and another of 50 bases, the cis-acting ribozyme. (B) Ribozyme in vitro assays. Lane a (control) shows the CCR5 mRNA (1199 bases) after incubation with Mg2+ for 4 h at 37 °C, and lane b shows effects of incubating the CCR5 ribozyme with this mRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1 for 4 h. Lane c (control) shows the CXCR4 mRNA (1175 bases) after incubation, and lane d shows the effects of incubation of the CXCR4 ribozyme with this mRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1 for 4 h. (C) Ribozyme specificity studies. Lanes a and b show the effect of incubating CCR5 mRNA with CXCR4 ribozyme (lane a, control stopped at zero time; lane b, after overnight incubation in 24 mM Mg2+ at 37 °C). Lanes c and d show the effect of incubating CXCR4 mRNA with CCR5 ribozyme (lane c, control stopped at zero time; lane d, after incubating overnight in 24 mM Mg2+ at 37 °C).

Activity in vitro of the trans-ribozymes on CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNA

In order to study the in vitro activity of the ribozymes, CXCR4 and CCR5 cDNAs were produced by RT–PCR from mRNA obtained from human PBMCs. The PCR products from CXCR4 and CCR5 [26,30] were cloned directly into pcDNA3 and were sequenced. T7 RNA polymerase was used to make transcripts from linearized templates, and these served as targets for the ribozymes for in vitro assay.

Figure 3(B) (lanes a and b) shows the effect of incubating CCR5 ribozyme with CCR5 mRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1. Because the ribozyme was designed to cleave at the second GUC site in the target, the reaction produces two fragments: one of 109 bases, and another of 1090. Almost complete cleavage of the target is seen to occur within 4 h (t1/2=40 min). Lanes c and d of Figure 3(B) show a similar experiment, but this time with CXCR4 ribozyme and CXCR4 mRNA, again at a 1:1 molar ratio. In this case, cleavage at the 14th GUC site along the sequence results in the target being cut into two similarly sized fragments: 611 and 564 bases (t1/2=55 min). Both ribozymes cleave their respective substrates totally within 4 h at a 1:10 molar ratio (t1/2=80 and 70 min for CCR5 and CXCR4 respectively). The ribozymes were specific for their targets, as neither cleavage of CXCR4 mRNA nor that of CCR5 occurred when incubated with CCR5 ribozyme or CXCR4 ribozyme respectively (Figure 3C).

Production of ribozymes and single-stranded antisense RNAs in PBMCs using T7 RNA polymerase

In order to generate the ribozymes and antisense molecules in PBMCs, vectors were engineered for delivery, based on the T7 RNA polymerase system. The T7 RNA polymerase gene was cloned into pCS2 [22] to produce pCS2P, and this vector was used to generate T7 RNA polymerase from a CMV promoter. In addition, an autocatalytic system for polymerase production using a plasmid pZEQ was constructed based on the pT7T7 vector of work published previously [24]. In this autocatalytic system, T7 RNA polymerase is manufactured in the cell's cytoplasm through an associated IRES sequence, placed downstream of a T7 promoter, but upstream of the T7 RNA polymerase sequence. Once this system is primed, large amounts of polymerase can be obtained because of positive feedback. pCS2P and pCS2P+pZEQ were tested for their capacity to produce T7 RNA polymerase in PBMCs after transfection. Western blotting of whole-cell extracts with a polyclonal antibody [23] showed that T7 RNA polymerase was made by pCS2P, and that substantially more was made with a combination of pCS2P+pZEQ [31].

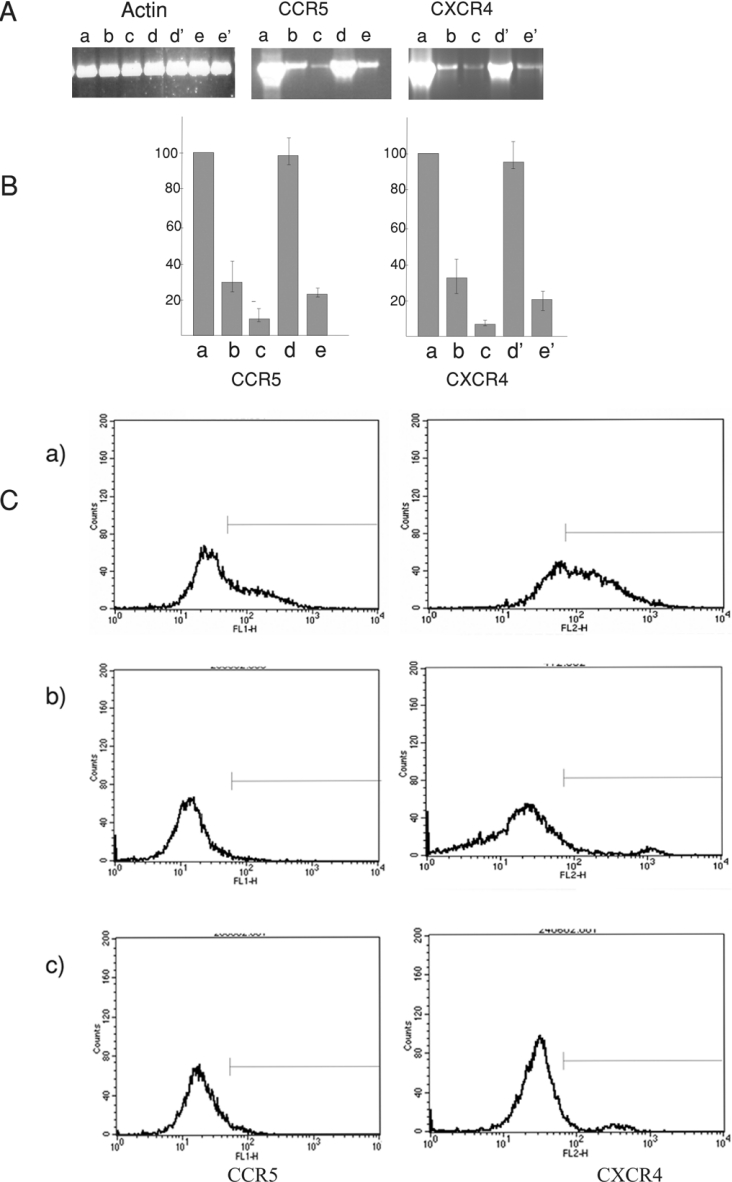

In order to study the effects of the ribozymes in PBMCs, a plasmid was constructed by inserting the complete CXCR4 ribozyme-generating cassette in the vector pCCR5Rz, upstream of the CCR5 ribozyme-producing cassette, forming pCXCR4/CCR5Rz. PBMCs were transfected with pCXCR4/CCR5Rz together with either pCS2P or pCS2P+pZEQ to generate trans-acting ribozymes against both CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNAs (Figure 4). The plasmid pCS2P produces the initial T7 RNA polymerase, and the additional presence of pZEQ gives maximum polymerase levels, therefore increasing ribozyme or antisense production. It is clear that the autocatalytic systems produce a greater reduction in receptor mRNA levels (Figure 4A, compare lanes c and b in the CCR5 and CXCR4 panels); the average mRNA reduction (n=3) was 92% for CXCR4 and 95% for CCR5 (Figure 4B, bars a, b and c). CCR5 mRNA depletion, using CCR5 ribozyme produced from the double-ribozyme plasmid, pCXCR4/CCR5Rz, was similar to that seen when the CCR5 ribozyme was produced from the single-ribozyme plasmid, pCCR5Rz (results not shown), indicating that the sequential addition of the ribozyme-generating cassettes, both requiring T7 polymerase, had little effect on overall ribozyme production and activity.

Figure 4. CXCR4 and CCR5 ribozyme and antisense activity in human PBMCs.

(A) Agarose gel results of RT–PCR using primers specific for mRNAs of actin, CCR5 and CXCR4. Lane a, control cells transfected with pCS2P+pZEQ expression systems; lane b, cells containing pCS2P+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz; lane c, cells containing pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz; lane d, cells containing pCS2P+pCCR5As; lane d', cells containing pCS2P+pCCCR5As; lane e, cells containing pCS2P+pZEQ+CCR5 antisense system; lane e', cells containing pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4As. (B) Quantification of the CCR5 and CXCR4 RT–PCR products produced in (A) as a percentage of the control. The same lettering is used as in (A) to identify the samples. Similar values were obtained from Lightcycler data after normalizing with actin as a control. (C) Results of FACS scan for CCR5 and CXCR4: (a) control cells, (b) cells transfected with pCS2P+pZEQ+pCCR5As/pCXCR4As, and (c) cells transfected with pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz. Quantification shows that the cells transfected with pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz have CCR5 levels depleted by up to 92% and CXCR4 levels depleted by up to 70%. The pCCR5As- or pCXCR4As-transfected cells have CCR5 levels lowered by 78% and CXCR4 levels lowered by 55% respectively.

Small single-stranded antisense RNAs were also effective in bringing about CCR5 and CXCR4 mRNA depletion. Little change in receptor mRNA level was seen when pCS2P was used to generate the antisense molecules (Figure 4A, lanes d and d'). However, when an autocatalytic system was employed, which made more polymerase, a clear reduction was evident (Figure 4A, lanes e and e'). In these cases, CXCR4 and CCR5 were reduced by 80% of the control values (Figure 4B, lanes d' and e', and lanes d and e). Antisense RNA against CCR5 was tested for its specificity by assaying both CCR5 and CXCR4 mRNA levels in transfected cells. Whereas a reduction (50–70%) was seen in CCR5 mRNA, the level of CXCR4 mRNA remained unchanged. Antisense RNA against CXCR4 was tested in a likewise manner and was found to be specific for its target.

Cell-surface receptor expression using FACS analysis

In order to investigate whether the ribozymes had potential for inhibiting the expression of cell-surface receptors on cells that are targeted naturally by HIV, PBMCs were isolated from individual donors and were assayed for CCR5 and CXCR4 levels. Both types of receptor varied greatly in their initial levels of expression and in their behavioural characteristics during cell culture of PBMCs, reflecting the fact that individuals differ widely in the kinetics of receptor expression [1,32]. The levels of receptors were followed after stimulation, and the greatest degree of inhibition, varying between 50 and 90% for each individual, was generally found to lie between 3 and 7 days after transfection.

Challenge with HIV of PBMCs transfected with ribozymes

Cells were challenged with virus on day 5, which was a compromise and chosen because both receptor levels generally fell around this time (results not shown). FACS results that demonstrate the reduction in cell-surface CXCR4 and CCR5 due to ribozyme production are shown in Figure 4(C). In order to determine the effects of ribozyme treatment on HIV infection, HIV-1 strains LAI and SF162 were used that bind to CXCR4 and CCR5 respectively.

The direct detection of p24 was used for the evaluation of HIV infection because our aim was to inhibit the productive infection of the virus, and the p24 assay can reliably reflect this aspect, unlike the reverse-polymerase assay or the detection of incorporated HIV DNA. In all of these experiments, cells transfected with pCS2P+pZEQ or pCS2P were used as controls in addition to non-transfected cells. Overall, the different controls gave similar results, confirming that the experimental procedures did not affect the cells' survival or their susceptibility to HIV-1. Cell viability was checked continuously using Trypan Blue staining, and was constantly over 85%. The live cell number was taken as the true cell number for each experiment. The results, shown in Table 1, demonstrate a clear inhibition of HIV-1 infection in PBMCs. On average, the LAI strain was inhibited by 75% and the SF162 strain was inhibited by 68%.

Table 1. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication in PBMCs; p24 assay results expressed as percentage of non-transfected control.

Results are shown of p24 assays performed on PMBCs, isolated from individual donors, and challenged with HIV-1 strains LA1 (X4 strain) and SF162 (R5 strain). Cells from each donor were separated into three aliquots: a non-transfected control, a transfected sample containing a polymerase-generating system pCS2P+pZEQ, and a transfected sample containing a polymerase-generating system and ribozyme, pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz. Some aliquots were not followed through to the end of the protocol because of technical difficulties, and the p24 level was not determined on these samples (ND).

| (a) HIV-1 strain SF162 | ||

|---|---|---|

| p24 (%) | ||

| Donor | Transfection with pCS2P+pZEQ | Transfection with pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5 Rz |

| A | ND | 19 |

| B | 61 | 13 |

| C | 223 | 32 |

| D | 118 | 87 |

| E | ND | 49 |

| (b) HIV-1 strain LA1 | ||

| p24 (%) | ||

| Donor | Transfection with pCS2P+pZEQ | Transfection with pCS2P+pZEQ+pCXCR4/CCR5Rz |

| F | 89 | 53 |

| G | 83 | 19 |

| H | 163 | 24 |

| I | 70 | 57 |

| J | 113 | 44 |

DISCUSSION

In order to reduce HIV replication, it is important to target both T-tropic and M-tropic strains of HIV. M-tropic strains of HIV initially infect the macrophages with minimal cytopathic effects. At this stage, HIV actively replicates in the macrophages, while staying latent [32,33]. T-tropic HIV strains are associated with CD4+ cell decline and progression to AIDS. The approaches that we have developed address both of these issues because they focus on the major receptor for T-tropic strains, CXCR4, as well as that for M-tropic strains, CCR5.

Using ribozyme-based technology described in the present paper, our data demonstrate a simultaneous depletion in the expression of both CCR5 and CXCR4, which leads to a significant inhibition of HIV-1 infection in PBMCs. PBMCs represent a mixed population of cell types, and, in culture, a complicated series of interrelationships are generated. Despite the inherent problems of using these cells and variations between donor samples, we felt that this approach would be best rather than using cell lines, because PBMCs are the natural host cells of the virus in adults, and thus the results obtained would be more meaningful in a clinical context.

Individuals who do not have a functional CCR5 lead a normal and healthy life, indicating that the activity of CCR5 is dispensable from birth. This may not be true for CXCR4, which appears to be necessary in foetal mice for cardiac development, endothelial cell migration and vasculogenesis [34,35]. However, there is no evidence to suggest that such requirements occur in humans [13], and loss of CXCR4 resulting from intrakines can be tolerated in cell lines. Moreover, MT4 cells retain normal biological features after down-regulation of CXCR4 [14]. The approaches we have pursued are aimed at the transient removal of this receptor, which can be used to treat adult cells in vitro and in vivo, and have a much lower risk than the use of viral vectors for ribozyme delivery that aim at a permanent removal of this particular receptor [10,14,36].

The ribozyme that we have produced against CCR5 is highly active in vitro and its activity is greater than that of previously reported ribozymes to this target area, as far as we can tell from the published data [7–9]. The greater activity may be due to the design, where we have used minimal lengths of stems I and II, stability loops and a cis-cleaving ribozyme to produce a well-defined and stable trans-acting molecule.

We have shown that a substantial decrease in mRNA levels for CXCR4 and CCR5 can be obtained with the ribozymes approx. 2 days after transfection of PBMCs in culture. This loss is reflected in a reduction of cell-surface receptors, which occurs between 3 and 5 days after transfection, depending on donor sample. The variations that we see are likely to come from the interrelationships occurring in a mixed cell population, variable production of cytokines, and differences in receptor recycling, which all contribute to the complexity from using PBMCs, and more work is need to unravel the issues touched upon. Although loss of the receptors on the cell surface was not total under the conditions that we employed, it was sufficient to inhibit HIV replication, and there was a clear relationship between loss of a particular receptor class and the strain of HIV. Thus the use of these ribozymes, directed at both receptor molecules, looks especially promising as a route for tackling HIV-1 entry and replication.

We also investigated the use of small single-stranded antisense RNA molecules to target the same sequences on receptor mRNAs as those used by the ribozymes, so that the activities could be compared, and differences in target accessibility would not complicate the issue [37]. Initially, we assumed that the small single-stranded RNA molecules would work by translational inhibition, but we were surprised to find that they resulted in degradation of the target [31]. Our results demonstrate that these RNAs, having only 12–13 complementary nucleotides, are active and highly specific, although they are less active than ribozymes when produced in similar amounts.

The mechanism by which the antisense RNAs work has yet to be elucidated, although they may operate through RNAi. RNAi is induced in cells towards a specific target by introducing hairpin RNA molecules for the specific mRNA [38]. The hairpin RNA molecules are then cleaved into siRNAs by the activity of a dicer enzyme. These siRNAs are then incorporated into a RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex), which is later activated and cleaves the target mRNA [15,20]. The mechanism is highly specific, and the change of a single base can disrupt the mechanism [39,40]. Under certain circumstances, small single-stranded RNA molecules can also enter this pathway and participate in RNAi [41,42].

The antisense molecules produced in the present study share structural features with some of the hairpin RNA molecules used for RNAi [43,44], but they are also different. The secondary structure of the antisense molecules incorporates a 5′ stability loop, but the loop does not extend like a hairpin, which involves the rest of the molecule. Following from the loop is a stretch of 12–13 nucleotides, complementary to the target. This is smaller than the 21–22 nucleotides that are considered to be a requirement for RNAi [45–47]. The antisense molecules are produced through the activity of a cis-acting ribozyme, so that their 3′ ends terminate with 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate; this should not prevent them from entering the RNAi pathway, because it has been shown that the 3′ end of siRNAs can be modified without affecting their activity [42]. Modification of siRNAs at their 5′ ends seems to be more important, especially phosphorylation, which potentiates their activity [41,42]. The antisense molecules that we have produced using the T7 system would have a phosphorylated 5′-terminus when produced in the cell, so this might favour their recruitment to the RNAi system.

It has been well established that, for siRNAs, the cleavage site on the target is determined by the position of the 5′ of the dsRNA molecule which acts as a guide [18]. In the single-stranded molecules that we have made, the 5′ end functions as a stability loop and is positioned some 12–14 nt away from the start of the region that is complementary to the target. Although we do not know how our molecules work nor the positions of the cleavage sites on their respective targets, it seems unlikely that the extra nucleotides at the 5′ end would have much of a role in targeting these molecules.

For RNAi to function, it is generally agreed that the siRNA molecules are required to have a high degree of complementarity to their target, and even changes in single bases can disrupt their function [18,47]. The antisense molecules that we have made are only partially complementary to their target, although they are fully complementary over a small stretch. So, from this evidence as well, it is unclear whether the antisense molecules that we have made utilize the RNAi pathway for their activity or are part of a different system for RNA degradation. Despite the fact that we are currently ignorant of their mode of action, we think that molecules such as these may be useful in allowing a wide range of novel molecular structures to be engineered for antisense studies. Furthermore, the design of such molecules opens up the possibility of exploiting many other types of production system apart from T7 that was used in the present study.

We think that the ribozymes and antisense molecules described here, while not envisaged as cures, have great potential for the long-term treatment of patients infected with HIV, ameliorating the condition through a reduction in viral load. Many conventional drug treatments aimed at inhibiting enzymes that are unique to the virus, and have been shown previously to be very effective on their own, are now being abandoned in favour of multidrug treatment regimes because the virus has adapted to them, and this will always be a problem when targeting virus-specific proteins. It therefore seems sensible that radical alternative approaches are pursued as well, and preventing the formation of mammalian receptors that HIV needs in order to gain access to cells is one way forward. To this end, the ribozymes described in the present paper are being developed further for delivery to patients' cells with customized transfection reagents, with the eventual aim being to take these products into clinical trials and to assess their effectiveness in reducing viral load.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank the Special Trustees of St Bartholomew's and St Mark's Hospitals and, especially, Professor A. J. Pinching of Queen Mary College for their support, Dr P. Marsh (King's College London) for discussions, Dr R. Rupp (Friedrich Miescher Laboratory, Max Planck Institute, Tübingen, Germany), for the pCS2 vectors, Dr F. Studier (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY, U.S.A.) for the pT7Auto-2 and pAR1173 vectors and the T7 polymerase antibody, and Dr B. Moss (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.) for the pTM1 vector. We also thank the Medical Research Council, UK, for providing the HIV strains. P. E. and A. Q. declare a financial interest in Viratis.

References

- 1.Zaitseva M., Peden K., Golding H. HIV coreceptors: role of structure, posttranslational modifications, and internalization in viral-cell fusion and as targets for entry inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1614:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagnarelli P., Fiorelli L., Vecchi M., Monachetti A., Menzo S., Clementi M. Analysis of the functional relationship between V3 loop and gp120 context with regard to human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor usage using naturally selected sequences and different viral backbones. Virology. 2003;307:328–340. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen B., Vogan E. M., Gong H., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C., Harrison S. C. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature (London) 2005;433:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meister S., Otto C., Papkalla A., Krumbiegel M., Pohlmann S., Kirchhoff F. Basic amino acid residues in the V3 loop of simian immunodeficiency virus envelope alter viral coreceptor tropism and infectivity but do not allow efficient utilization of CXCR4 as entry cofactor. Virology. 2001;284:287–296. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samson M., Libert F., Doranz B. J., Rucker J., Liesnard C., Farber C. M., Saragosti S., Lapoumeroulie C., Cognaux J., Forceille C., et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature (London) 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng H. K., Unutmaz D., Kewalramani V. N., Littman D. R. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature (London) 1997;388:296–300. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai J., Gorantla S., Banda N., Cagnon L., Rossi J., Akkina R. Characterization of anti-CCR5 ribozyme-transduced CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro and in a SCID-hu mouse model in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2000;1:244–254. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez M. A., Serrano F., Llorente M., Abad J. L., Garcia-Ortiz M. J., Bernad A. A hammerhead ribozyme targeted to the human chemokine receptor CCR5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;251:592–596. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goila R., Banerjea A. C. Sequence specific cleavage of the HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 gene by a hammer-head ribozyme and a DNA-enzyme: inhibition of the coreceptor function by DNA-enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M. J., Bauer G., Michienzi A., Yee J. K., Lee N. S., Kim J., Li S., Castanotto D., Zaia J., Rossi J. J. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by lentiviral vectors expressing Pol III-promoted anti-HIV RNAs. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:196–206. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez J., Patkaniowska A., Urlaub H., Luhrmann R., Tuschl T. Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi. Cell. 2002;110:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor R. I., Sheridan K. E., Ceradini D., Choe S., Landau N. R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger E. A., Murphy P. M., Farber J. M. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing H. C., Xu X. Y., Liu Z., Wang Q. H., Yu M., Si C. W. Down-regulation of CXCR4 expression in MT4 cells by a recombinant vector expressing antisense RNA to CXCR4 and its potential anti-HIV-1 effect. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;57:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannon G. J. RNA interference. Nature (London) 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M. K., Kostas S. A., Driver S. E., Mello C. C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature (London) 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterhouse P. M., Wang M. B., Lough T. Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature (London) 2001;411:834–842. doi: 10.1038/35081168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbashir S. M., Harborth J., Weber K., Tuschl T. Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. Methods. 2002;26:199–213. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng Y., Wagner E. J., Cullen B. R. Both natural and designed micro RNAs can inhibit the expression of cognate mRNAs when expressed in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartel D. P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchuk D., Drumm M., Saulino A., Collins F. S. Construction of T-vectors, a rapid and general system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rupp R. A., Snider L., Weintraub H. Xenopus embryos regulate the nuclear localization of XMyoD. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1311–1323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubendorff J. W., Studier F. W. Creation of a T7 autogene: cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase under control of its cognate promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;219:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90857-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X., Li Y., Xiong K., Wagner T. E. A self-initiating eukaryotic transient gene expression system based on contransfection of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and DNA vectors containing a T7 autogene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.11.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss B., Elroy-Stein O., Mizukami T., Alexander W. A., Fuerst T. R. Product review. New mammalian expression vectors. Nature (London) 1990;348:91–92. doi: 10.1038/348091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samson M., Labbe O., Mollereau C., Vassart G., Parmentier M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a new human CC-chemokine receptor gene. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3362–3367. doi: 10.1021/bi952950g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaeger J. A., Turner D. H., Zuker M. Predicting optimal and suboptimal secondary structure for RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:281–306. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amarzguioui M., Brede G., Babaie E., Grotli M., Sproat B., Prydz H. Secondary structure prediction and in vitro accessibility of mRNA as tools in the selection of target sites for ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4113–4124. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chowrira B. M., Pavco P. A., McSwiggen J. A. In vitro and in vivo comparison of hammerhead, hairpin, and hepatitis delta virus self-processing ribozyme cassettes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:25856–25864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Federsppiel B., Melhado I. G., Duncan A. M., Delaney A., Schappert K., Clark-Lewis I., Jirik F. R. Molecular cloning of the cDNA and chromosomal localization of the gene for a putative seven-transmembrane segment (7-TMS) receptor isolated from human spleen. Genomics. 1993;16:707–712. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qureshi A. University of London; 2003. Ribozymes against CCR5 and CXCR4 for inhibition of HIV-1 replication. Ph.D. Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langenkamp A., Nagata K., Murphy K., Wu L., Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F. Kinetics and expression patterns of chemokine receptors in human CD4+ T lymphocytes primed by myeloid or plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:474–482. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rich E. A., Orenstein J. M., Jeang K. T. A macrophage-tropic HIV-1 that expresses green fluorescent protein and infects alveolar and blood monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002;9:721–726. doi: 10.1159/000067293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tachibana K., Hirota S., Iizasa H., Yoshida H., Kawabata K., Kataoka Y., Kitamura Y., Matsushima K., Yoshida N., Nishikawa S., et al. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature (London) 1998;393:591–594. doi: 10.1038/31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou Y. R., Kottmann A. H., Kuroda M., Taniuchi I., Littman D. R. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature (London) 1998;393:595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burke B., Sumner S., Maitland N., Lewis C. E. Macrophages in gene therapy: cellular delivery vehicles and in vivo targets. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2002;72:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kretschmer-Kazemi F. R., Sczakiel G. The activity of siRNA in mammalian cells is related to structural target accessibility: a comparison with antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4417–4424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutvagner G., Zamore P. D. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elbashir S. M., Harborth J., Lendeckel W., Yalcin A., Weber K., Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature (London) 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randall G., Grakoui A., Rice C. M. Clearance of replicating hepatitis C virus replicon RNAs in cell culture by small interfering RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:235–240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235524100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez M. A., Gutierrez A., Armand-Ugon M., Blanco J., Parera M., Gomez J., Clotet B., Este J. A. Suppression of chemokine receptor expression by RNA interference allows for inhibition of HIV-1 replication. AIDS. 2002;16:2385–2390. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200212060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwarz D. S., Hutvagner G., Haley B., Zamore P. D. Evidence that siRNAs function as guides, not primers, in the Drosophila and human RNAi pathways. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Y. Mammalian RNAi for the masses. Trends Genet. 2003;19:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ichim T. E., Qian H., Popov I. A., Rycerz K., Zheng X., White D., Zhong R. RNA interference: a potent tool for gene-specific therapeutics. Am. J. Transplant. 2004;4:1227–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elbashir S. M., Martinez J., Patkaniowska A., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Functional anatomy of siRNAs for mediating efficient RNAi in Drosophila melanogaster embryo lysate. EMBO J. 2001;20:6877–6888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paddison P. J., Caudy A. A., Bernstein E., Hannon G. J., Conklin D. S. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) induce sequence-specific silencing in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16:948–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.981002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tijsterman M., Ketting R. F., Okihara K. L., Sijen T., Plasterk R. H. RNA helicase MUT-14-dependent gene silencing triggered in C. elegans by short antisense RNAs. Science. 2002;295:694–697. doi: 10.1126/science.1067534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.