Abstract

A temperature-sensitive (ts) mutation was identified within the 5′-untranslated region of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) RNA. The mutation destabilizes a stem-loop structure recently identified as a cis-acting replication element (cre). Genetic analyses indicated that the ts defect in virus replication could be complemented. Thus, the FMDV cre can function in trans. It is suggested that the cre be renamed a 3B-uridylylation site (bus).

Picornaviruses have a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of around 8 kb. The genome is replicated in two stages: initially, a negative-sense transcript is produced, and it is then used as the template to make new positive strands. Both positive- and negative-sense transcripts are linked at their 5′ end to the virus-encoded peptide VPg (3B). It is believed that structures at both the 5′ terminus and the 3′ terminus of the viral genome are required in order to direct the recognition of the RNA by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (3D). In the last few years, evidence has accumulated for the presence of additional RNA structures that are required for RNA replication. These are located away from the RNA termini and are within the coding region of several different picornavirus genomes. The initial evidence for such an element within picornavirus RNAs was the observation that certain sequences, within the P1-coding sequence of human rhinovirus 14 (HRV-14), were required to achieve efficient replication of replicons based on this virus (14). This contrasts with studies on poliovirus (PV) that have demonstrated that the entire capsid-coding sequence can be deleted without blocking RNA replication (1). Further work identified the requirement for a specific stem-loop structure, which was named a cis-acting replication element (cre), located within the 1D (VP1) coding region of the HRV-14 RNA genome (15). Subsequently, analogous cre motifs have been identified within the coding region of other picornavirus RNAs (7, 8, 10). These cre structures are located within different regions of the genome. The cre motifs from HRV-14, HRV-2, cardioviruses, and PV are within the regions coding for 1D, 2A, 1B, and 2C, respectively. However, the cre structures can be moved without blocking function. For example, mutagenesis of the PV cre within the 2C sequence blocked RNA replication, but when the wild-type (wt) cre was introduced into the P1-coding region, the ability of the mutant PV genome to replicate was partially restored (8). It has recently been shown that the PV and HRV-2 cre structures act as templates for the uridylylation of VPg (3B) in vitro, and it is believed that this activity is an essential step in the process of RNA replication (7, 16).

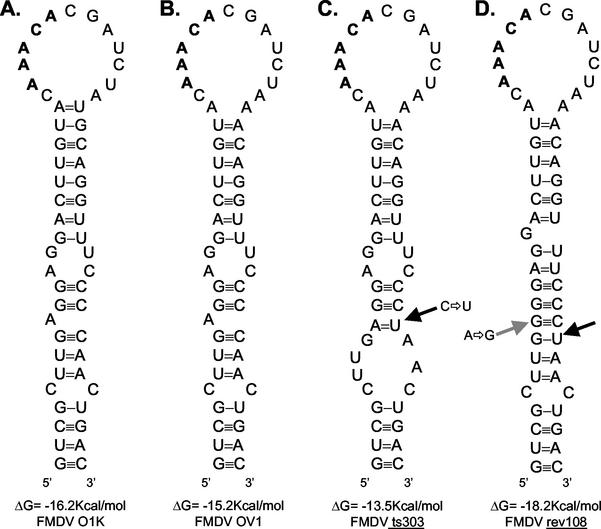

The development of replicons based on foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) showed that the entire coding sequence for the FMDV Leader protein and 94% of the FMDV P1 sequence could be deleted without any adverse effect on the replication of the viral RNA (13). These studies indicated that if, as expected, there is a cre present within the FMDV genome then it must be present either within the coding region for the nonstructural proteins or within noncoding sequences. Each of the cre structures defined within the enterovirus, rhinovirus, and cardiovirus RNAs includes a conserved sequence motif, AAACA, located within a loop at the end of a stable stem structure (total size, about 40 to 60 nucleotides [nt] [7, 17]). However, the conservation of this motif is not absolute. For example, in the Sabin strain of PV (type 2), instead of the AAACA motif, the sequence AAGCA is found at this position of the cre and in bovine enterovirus the corresponding sequence is AAGAA. Sequence analysis of the aligned genome sequences of FMDV indicated that there are several places in the FMDV sequences (outside the L-P1 coding region) where a copy of the AAACA motif is highly conserved among different virus isolates. Interestingly, at some of these sites and in certain isolates, the sequence at these positions is AAGCA, as found in the cre sequence of the PV Sabin2 sequence. These motifs occur in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) and within the coding sequences for 2B, 2C, and 3D within the FMDV genome. Recently, a computer prediction for a cre within the 2C-coding region of FMDV was published (22). However, Mason et al. (12) have now reported functional evidence for a cre, containing the AAACA sequence, within the FMDV genome. In contrast to the other picornavirus cre structures, the FMDV cre is located within the 5′-UTR, just upstream of the internal ribosome entry site. The stem-loop structure corresponding to the FMDV cre from two type O FMDV RNAs is shown in Fig. 1A and B. We now report an analysis of a temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant of FMDV, ts303, which has a mutation within this cre structure. The critical feature of this mutant virus is that it can be complemented by coinfection with other ts mutants of FMDV; this indicates that the defective FMDV cre can be complemented in trans.

FIG. 1.

Predicted RNA secondary structures of wt and mutant FMDV cre motifs. (A) The predicted secondary structure of the 54-nt RNA sequence from the wt FMDV O1Kaufbeuren (O1K) strain that corresponds to the stem-loop structure identified as the FMDV cre (12) is represented. The sequence folded is nt 219 to 272 from GenBank accession number X00871. The corresponding structure for the wt OV1 strain is shown in panel B, and the structure for the RNA of the ts303 mutant of OV1 is depicted in panel C. The predicted structure for the sequence of the RNA from the non-ts revertant of ts303 called rev108 is shown in panel D. Each structure was derived by the m-fold program (23) by using the web site http://bioinfo.math.rpi.edu/∼mfold. The locations of the single point mutation in ts303 and the additional compensatory mutation in rev108 are indicated by arrows (C and D).

The mutant ts303 is a spontaneous ts mutant of the type O FMDV strain OV1 (small plaque phenotype). Other ts mutants used in this study are ts33, ts107, ts40, ts16, ts124, and ts115; each of these viruses is derived from a serotype O virus of the O1-Pacheco strain, and each has a large plaque phenotype that can be easily distinguished from the OV1 small plaque phenotype. The locations of the mutations in these viruses (see Tables 1 and 2) have been determined previously by using oligonucleotide-mapping data or electrophoretic-shift data from isoelectric focusing gels (9, 11, 19; A. M. Q. King, unpublished results). T1 oligonucleotide mapping and recombination mapping data indicated that the ts lesion in ts303 was located on the 5′ side of the coding region for VP4 (9). Direct sequencing of purified virion RNA from the wt and ts303 viruses between the coding sequence for VP4 and the poly(C) tract was performed. A single nucleotide substitution was identified (C to U) between the wt OV1 and ts303 sequences in this region (Fig. 1B and C). Support for the significance of this mutation was obtained through the isolation and sequence analysis of non-ts revertant viruses. One such virus, rev114, had a direct reversion of the mutation back to a C. However, another revertant virus, rev108, had acquired an additional mutation (A to G) some 38 bases upstream (Fig. 1D). Both of these mutations lie within the stem-loop structure identified as the cre of FMDV (12). It is apparent that the C-to-U transition in the ts303 RNA sequence weakens the stability of the stem-loop structure compared to that of the wt sequence (compare Fig. 1B and C). In contrast, the additional mutation in the rev108 RNA compensates for this modification and restores the stability of the cre structure (Fig. 1D).

TABLE 1.

Complementation analysis of ts303 by other ts FMDVs

| Rescued virusa | Rescue mutant virus | Geometric mean of CIb | Nc | td | Confidence limit (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ts33 (1B) | ts303 | 67.2 | 5 | 34 | >99.5e |

| ts124 (3C) | ts303 | 9.4 | 6 | 8.7 | >99.5e |

| ts16 (2C) | ts303 | 74.4 | 3 | 10.7 | >99.5e |

| ts115 (3D) | ts303 | 1.8 | 6 | 1.1 | <90 |

| ts303 (5′UTR) | ts124 | 94.9 | 6 | 11.8 | >99.5e |

| ts303 | ts16 | 44.6 | 3 | 7.8 | >99.0e |

| ts303 | ts115 | 77 | 3 | 7.6 | >99.0e |

The location of the ts defect is indicated in parentheses.

Each complementation index (CI) was calculated as described previously (20) by using the formula Individual CI = AMix/APT, where APT is the single infection titer of mutant A and AMix is the mixed infection titer of mutant A; CI values above 2 are considered significant.

N, number of independent CI determinations.

t = [log10 (mean CI)/standard deviation of log10 (mean CI)]×N0.5.

Complementation is significant at the > 95% confidence level according to Student's t test.

TABLE 2.

Lack of complementation of ts303 by ts capsid protein mutants

| Virus(es)a | Virus yield (PFU) determined at 37°Cc | Individual CIb,c |

|---|---|---|

| ts303 (5′UTR) | 2.1 × 105 | |

| ts33 (1B) | 5.3 × 102 | |

| ts107 (1C) | 2.4 × 102 | |

| ts40 (1D) | 1.1 × 102 | |

| ts303 + ts33 | 6.7 × 104, 3.3 × 104 | 0.3, 62.5 |

| ts303 + ts107 | 8.5 × 104, 1.9 × 104 | 0.4, 81.4 |

| ts303 + ts40 | 2.9 × 105, 1.5 × 104 | 1.4, 136 |

The location of the ts defect in each mutant virus is indicated in parentheses.

The individual CI values were determined as described in footnote b of Table 1 following infection of BHK cells with the indicated viruses at 41.5°C.

For the mixed virus infections, the values are listed in their respective order.

The yield of FMDV, determined by plaque assay at the permissive temperature of 37°C, from BHK cells infected at 41.7°C with ts303 was reduced by a factor of about 105 compared to the virus yield from infections performed with the same virus at 37°C. Only a modest decrease (<10-fold) in virus yield was observed from the parental wt virus at the higher temperature.

The ability of other ts mutant viruses to complement the mutation in ts303 was determined by classical complementation analysis (3, 4). For such assays, mixed infections of BHK cells at a high multiplicity of infection (50 PFU of each virus/cell) were performed at the nonpermissive temperature for 5 h and the yield of each virus was determined. The numbers of large plaques and small plaques generated in the mixed infections were individually determined at the permissive temperature (note that titrations performed at the nonpermissive temperature indicated that the frequency of recombination was so low that it did not significantly affect the virus titers measured at the permissive temperature). The correct identification of the virus plaques from a mixed infection was checked by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with a panel of type O-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). In such analyses, 18 of 18 small plaques (OV1 phenotype) that were picked showed a pattern of reactivity with the MAbs that matched that of the parental OV1 virus whereas 22 of 24 large plaques picked showed a pattern of reactivity identical to that of the parental O1 Pacheco virus (data not shown). The remaining two large plaques showed a pattern of reactivity consistent with a mixed infection, indicating that a small underestimation of the yield of ts303 was likely in these assays. The results from these mixed infections (Table 1) showed that ts303 was able to complement strongly other ts FMDV mutants that had defects in protein 1B (ts33), protein 2C (ts16), and protein 3C (ts124). In each case, the complementation indices were high and by statistical analysis were significant at a confidence level greater than 99.5%. Furthermore, the ts303 mutant (with the mutation in the cre) was strongly complemented by coinfection with mutants ts124 (in 3C), ts16 (in 2C), and ts115 (in 3D) (Table 1). Once again these effects were highly significant (confidence limits, >99%). Not all ts mutants were rescued by other ts mutants; for example, ts115 (mutation in 3D) was not rescued by ts303 (Table 1); this result is consistent with the reported inability to complement mutations within the poliovirus 3Dpol (2). It should be noted that ts115 is very restricted at the nonpermissive temperature; hence, its ability to complement ts303 indicates that a very low level of the complementing function needs to be present within the cell to achieve the 77-fold increase in the yield of ts303.

Each of the mutants that were shown to complement the ts303 mutation in Table 1 had a defect within one of the nonstructural proteins that reduces the ability of the RNA genome to be replicated. The RNA replication abilities of mutant viruses containing ts mutations within the capsid proteins were also examined (Table 2). Each of these mutants can be expected to display normal RNA replication (13). It was apparent that ts lesions in each of the major capsid proteins could be efficiently complemented by ts303 (Table 2). However, none of these mutants complemented ts303. Thus, ts mutant RNAs that were efficiently replicated failed to complement the defective cre structure in ts303.

Another feature of the properties of ts303 is that, in similar coinfection assays (at 41.5°C), it suppressed the yield of wt FMDV about 50-fold (Table 3). Thus, the ts303 mutant is trans-dominant. Other ts mutants, with defects in their capsid proteins, did not display this effect (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

ts303 has a trans-dominant phenotypea

| Virus | CI of indicated mutant/CI of ts303

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ts33 | ts107 | ts40 | wt | |

| ts303 | 54/0.4 | 61/0.4 | 284/1.6 | 0.02 |

| ts33 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| ts107 | 0.4 | 0.2 | ||

| ts40 | 0.9 | |||

The individual CI values shown were determined as described in footnote b of Table 1 following infection of BHK cells with the indicated viruses at 41.5°C. The individual virus yields were determined by plaque assays at 37°C. Mixtures for which the two components could be distinguished, on the basis of plaque morphology, have two indices. Note that this is a separate series of experiments from that shown in Table 2.

The ability of viruses to complement a ts mutation that lay within the noncoding region of the viral RNA was surprising, although the ability of defective picornavirus internal ribosome entry site elements to be complemented in trans by separate RNA transcripts has been reported previously (6, 18, 21). However, the mapping of the mutation in ts303 to the position of the cre provides another rationale for these results. The PV and HRV2 cre structures have been shown to act as the priming sites for the conversion (uridylylation) of VPg (3B) to VPgpU and/or VPgpUpU (7, 16, 17). This reaction requires, in vitro, the viral RNA polymerase 3D and its precursor 3CD together with VPg and the cre. A significant pool of the uridylylated products is generated within infected cells (5); hence, it is not clear why this reaction should function only in cis. Indeed, the observations reported here indicate that the function of a defective cre can be complemented in trans within FMDV-infected cells. It follows that the designation cre (cis-acting replication element) is inappropriate in the case of the FMDV structure.

During the initial characterization of the cre structures, it was reported that the replication-defective HRV-14 genomes lacking VP1 (the location of the HRV-14 cre) could not be complemented in trans within cells by superinfection with wt HRV-14 (14). Similarly, it has not been possible to observe complementation of mutations within the cre of PV replicons by using wt PV RNA (8, 17). However, it may be that competition between the rapidly replicating wt RNA and the cre-deficient replicon RNAs was too severe to allow an enhanced signal from the replicon RNA to be seen. Indeed, in the analyses presented here (Table 2), it was apparent that ts FMDV genomes that have defects in their capsid proteins but replicated efficiently at the RNA level were unable to complement ts303. An alternative explanation for the inability of these capsid mutants to complement ts303 is that the mutant capsid proteins were trans-dominant. However, this explanation seems unlikely since these mutants did not significantly suppress the yield of wt virus (Table 3). Thus, we believe that the restricted replication of both the complemented genome and the complementing RNA that occurs in cells coinfected with two appropriate (RNA replication defective) ts FMDVs under the nonpermissive conditions is likely to be a better system for detecting subtle effects. Indeed, this assay system clearly permitted the identification of significant trans-complementation of the defective FMDV cre.

It is not apparent why a defective FMDV cre should be trans-dominant (Table 3), but mutants of the PV cre within the 2C sequence have also been shown to have this property (Scott Crowder and Karla Kirkegaard, personal communication). It would appear that the genomes containing the defective cre structures partially sequester either sites or proteins within the cell that are required for optimal RNA replication. Presumably these factors do not become limiting when the replication of the genomes is restricted, as in the complementation analyses described here. It is apparent that the abilities of other picornavirus cre structures to function in trans should be reexamined. Since a defined function has been identified for the cre (7, 16), it may be appropriate to rename it a 3B-uridylylation site (bus).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the BBSRC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barclay, W., Q. Li, G. Hutchinson, D. Moon, A. Richardson, N. Percy, J. W. Almond, and D. J. Evans. 1998. Encapsidation studies of poliovirus subgenomic replicons. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1725-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein, H. D., P. Sarnow, and D. Baltimore. 1986. Genetic complementation among poliovirus mutants derived from an infectious cDNA clone. J. Virol. 60:1040-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burge, B. W., and E. R. Pfefferkorn. 1966. Complementation between temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus. Virology 30:214-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou, J. Y., and R. M. Martin. 1974. Complementation analysis of simian virus 40 mutants. J. Virol. 13:1101-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford, N. M., and D. Baltimore. 1983. Genome-linked protein VPg of poliovirus is present as free VPg and VPgpUpU in poliovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:7452-7455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drew, J., and G. J. Belsham. 1994. trans complementation of defective foot-and-mouth disease virus internal ribosome entry site elements. J. Virol. 68:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber, K., E. Wimmer, and A. V. Paul. 2001. Biochemical and genetic studies of the initiation of human rhinovirus 2 RNA replication: identification of a cis-replicating element in the coding sequence of 2Apro. J. Virol. 75:10979-10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodfellow, I., Y. Chaudhry, A. Richardson, J. Meredith, J. W. Almond, W. Barclay, and D. J. Evans. 2000. Identification of a cis-acting replication element within the poliovirus coding region. J. Virol. 74:4590-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King, A. M. Q., and J. W. I. Newman. 1980. Temperature-sensitive mutants of foot-and-mouth disease virus with altered structural polypeptides I. Identification by electrofocusing. J. Virol. 34:59-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobert, P.-E., N. Escriou, J. Ruelle, and T. Michiels. 1999. A coding RNA sequence acts as a replication signal in cardioviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11560-11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe, P. A., A. M. Q. King, D. McCahon, F. Brown, and J. W. I. Newman. 1981. Temperature-sensitive RNA polymerase mutants of a picornavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:4448-4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason, P. W., S. V. Bezborodova, and T. M. Henry. 2002. Identification and characterization of a cis-acting replication element (cre) adjacent to the IRES of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 76:9686-9694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McInerney, G. M., A. M. Q. King, N. Ross-Smith, and G. J. Belsham. 2000. Replication competent foot-and-mouth disease virus RNAs lacking capsid coding sequences. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1699-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKnight, K. L., and S. M. Lemon. 1996. Capsid coding sequence is required for efficient replication of human rhinovirus-14 RNA. J. Virol. 70:1941-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKnight, K. L., and S. M. Lemon. 1998. The rhinovirus type 14 genome contains an internally located RNA structure that is required for viral replication. RNA 4:1569-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul, A. V., E. Rieder, D. W. Kim, J. H. van Boom, and E. Wimmer. 2000. Identification of an RNA hairpin in poliovirus RNA that serves as the primary template in the in vitro uridylylation of VPg. J. Virol. 74:10359-10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieder, E., A. V. Paul, D. W. Kim, J. H. van Boom, and E. Wimmer. 2000. Genetic and biochemical studies of poliovirus cis-acting replication element cre in relation to VPg uridylylation. J. Virol. 74:10371-10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts, L. O., and G. J. Belsham. 1997. Complementation of defective picornavirus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) elements by the co-expression of fragments of the IRES. Virology 227:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders, K., and A. M. Q. King. 1982. Guanidine-resistant mutants of aphthovirus induce the synthesis of an altered nonstructural polypeptide, P34. J. Virol. 42:389-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snedecor, G. W. 1956. Statistical methods (applied to experiments in agriculture and biology), 5th ed, p. 320-328. Iowa State College Press, Ames.

- 21.Stone, D., J. W. Almond, J. K. Brangwyn, and G. J. Belsham. 1993. trans complementation of cap-independent translation directed by poliovirus 5′ noncoding region deletion mutants; evidence for RNA-RNA interactions. J. Virol. 67:6215-6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witwer, C., S. Rauscher, I. L. Hofacker, and P. F. Stadler. 2001. Conserved RNA secondary structures in Picornaviridae genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:5079-5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuker, M., D. H. Mathews, and D. H. Turner. 1999. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide, p. 11-43. In J. Barciszewski and B. F. C. Clark (ed.), RNA biochemistry and bio/technology. NATO ASI Series. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.