Abstract

Plant XETs [XG (xyloglucan) endotransglycosylases] catalyse the transglycosylation from a XG donor to a XG or low-molecular-mass XG fragment as the acceptor, and are thought to be important enzymes in the formation and remodelling of the cellulose-XG three-dimensional network in the primary plant cell wall. Current methods to assay XET activity use the XG polysaccharide as the donor substrate, and present limitations for kinetic and mechanistic studies of XET action due to the polymeric and polydisperse nature of the substrate. A novel activity assay based on HPCE (high performance capillary electrophoresis), in conjunction with a defined low-molecular-mass XGO {XG oligosaccharide; (XXXGXXXG, where G=Glcβ1,4- and X=[Xylα1,6]Glcβ1,4-)} as the glycosyl donor and a heptasaccharide derivatized with ANTS [8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulphonic acid; (XXXG-ANTS)] as the acceptor substrate was developed and validated. The recombinant enzyme PttXET16A from Populus tremula x tremuloides (hybrid aspen) was characterized using the donor/acceptor pair indicated above, for which preparative scale syntheses have been optimized. The low-molecular-mass donor underwent a single transglycosylation reaction to the acceptor substrate under initial-rate conditions, with a pH optimum at 5.0 and maximal activity between 30 and 40 °C. Kinetic data are best explained by a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism with substrate inhibition by both donor and acceptor. This is the first assay for XETs using a donor substrate other than polymeric XG, enabling quantitative kinetic analysis of different XGO donors for specificity, and subsite mapping studies of XET enzymes.

Keywords: assay, capillary electrophoresis, ping-pong mechanism, xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET), xyloglucan oligosaccharides (XGOs)

Abbreviations: ANTS, 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulphonic acid; EOF, electro-osmotic flow; HPCE, high performance capillary electrophoresis; XEH, XG endohydrolase; XET, XG endotransglycosylase; XG, xyloglucan; XGOs, XG oligosaccharides; XGOol, reduced XGO

INTRODUCTION

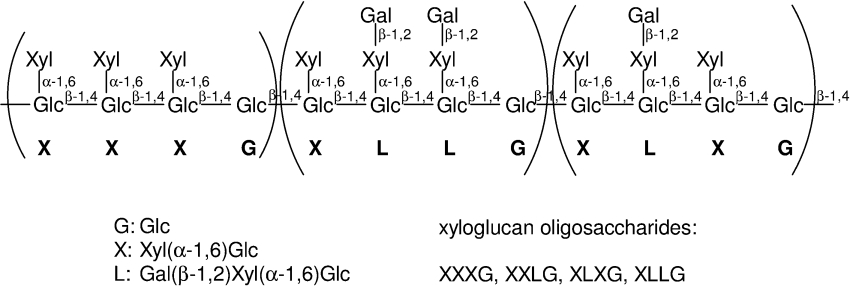

XG (xyloglucan) is one of the major hemicellulosic polysaccharides in dicotyledonous plant cell walls. It forms hydrogen bonds with cellulose microfibrils and provides a molecular tether between adjacent microfibrils by forming a three-dimensional cellulose-XG network [1,2]. XG polysaccharide consists of a β-1,4-linked D-glucosyl backbone that is highly C-6 substituted with α-D-xylosyl or β-D-galactosyl-(1→2)-α-D-xylosyl residues (Figure 1) [3]. Additionally, some galactosyl units can be C-2 substituted with α-L-fucosyl residues [4].

Figure 1. Structure and nomenclature of XG and its constituent oligosaccharides.

Oligosaccharides are named by the code letters corresponding to each glucosyl unit of the backbone substituted with other sugars (if any) on the side chain [3]. XG can also be α-1,2-L-fucosylated on some galactosyl residues.

XETs (xyloglucan endotransglycosylases, EC 2.4.1.207) are thought to be important enzymes in the formation and remodelling of the XG network by cleaving and reconnecting XG molecules during cell wall morphogenesis [5]. XET enzymes belong to the glycoside hydrolase family 16 [6] and catalyse the transglycosylation from a XG donor to a XG acceptor [7–9]. The enzymatic mechanism involves the cleavage of a β-1,4 linkage of the polyglucosyl main chain of the XG donor, followed by transfer of the new chain end to the 4-OH of the glucosyl unit at the non-reducing end of another XG molecule or a low-molecular-mass XG fragment (acceptor). The result is the formation of a new β-1,4 glycosidic bond with net retention of the anomeric configuration [10].

It has previously been postulated that the only donor for XET isolated from pea stems is a high-molecular-mass XG polysaccharide and that the minimum acceptor is the reduced form of the pentasaccharide XXG (Figure 1) [8]. However, it was shown that the mixed-function XET/xyloglucanase from the cotyledons of germinated nasturtium seeds can use the tetradeca- and tridecasaccharide XXXGXXXG or GXXGXXXG as the donor [11,12]. Additionally, it was reported that the best acceptor for various XETs from Arabidopsis, expressed in insect cells, is the reduced form of the nonasaccharide XLLG (Figure 1), using high-molecular-mass XG as the donor [13].

Since XET breaks XG chains and transfers the new chain ends to XG acceptors, no new reducing ends are generated, and conventional redox assays for glycoside hydrolases cannot be used to monitor XET activity. Various in vitro enzymatic assays have been developed based on the disproportionation of the XG-polymer upon transglycosylation as measured by gel-permeation chromatography [9,14], reduction of viscosity of the XG solution [15], or destaining of the blue-green-coloured iodine–XG complex due to the formation of shorter XGs [16].

Concomitantly, several assays based on tagged acceptors have been developed. Radiolabelled derivatives {reduced [3H]XGOs (XG oligosaccharides) [8] and [14C]fucosylated XGOs [7,15]} or fluorescent derivatives [9,14,17] were also prepared. The transglycosylation product containing the tag is separated from unreacted acceptor substrate by absorption on to a cellulose filter. Product binding to cellulose for separation and quantification requires a rather high-molecular mass. All of these methods use polymeric XG as the donor substrate, so that multiple turnovers render complex behaviour and prevent detailed kinetic evaluation.

Therefore current assays to evaluate XET activity present evident drawbacks, and a new method is required to study the mechanism of action and donor subsite recognition of XETs. Encouraged by the observation that the tetradecasaccharide XXXGXXXG can act as the donor substrate for the mixed-function XET/xyloglucanase (EC 2.4.1.207/EC 3.2.1.151) from nasturtium [12], we considered the development of an activity assay based on HPCE (high performance capillary electrophoresis) [18,19] to analyse low-molecular-mass xylogluco-oligosaccharide donors for kinetic studies of XETs. The tetradecasaccharide (4, Scheme 1) is used as the donor substrate, and the heptasaccharide XXXG derivatized with ANTS (8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulphonic acid) as the substrate acceptor (12, Scheme 1). Both acceptor and reaction (transglycosylation) products are tagged with the ANTS label, which provides a charge for the differential migration in capillary electrophoresis, and a chromophore/fluorophore for online spectrophotometric detection. After preparative syntheses of the donor and acceptor compounds and development of the XET activity assay, the novel HPCE method is applied to the kinetic characterization of XET16A from Populus tremula x tremuloides (hybrid aspen) [20,21]. It is shown that PttXET16A, which has no detectable hydrolase activity, catalyses transglycosylation following a ping-pong bi-bi kinetic mechanism.

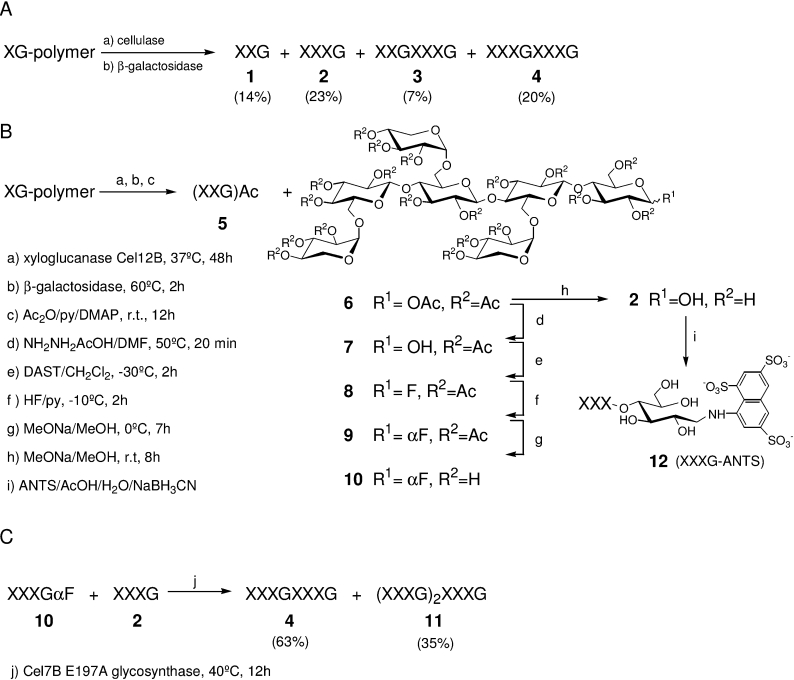

Scheme 1. Synthesis of XGOs.

(A) Preparation of the tetradecasaccharide (4) by enzymatic depolymerization of XG. (B) Synthesis of the α-glycosyl fluoride (10) and the XET acceptor (12). (C) Glycosynthase-catalysed preparation of the XET donor (4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and enzymes

XG from tamarind seeds and β-galactosidase from Aspergillus niger were purchased from Megazyme. Cellulase from Trichoderma reesei and ANTS (disodium salt) were from Fluka. All other chemicals used in the synthetic procedures were synthetic grade reagents. PttXET16A from P. tremula x tremuloides was recombinantly expressed in Pichia pastoris cells and purified as previously described [21]. Enzyme concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using a calculated ϵ of 72970 M−1·cm−1 [22]. The cellulase mutant, Cel7B E197A, from Humicola insolens and xyloglucanase, Cel12B, from Aspergillus aculeatus were gifts from Novozymes A/S Denmark.

Synthesis of donor and acceptor substrates (Scheme 1)

Low-molecular-mass XGOs were obtained by enzymatic depolymerization of tamarind seed XG. The tetradecasaccharide (4) was either prepared by controlled enzymatic depolymerization of XG by T. reesei cellulase followed by degalactosylation with A. niger β-galactosidase, or by glycosynthase-catalysed coupling of an α-heptasaccharyl fluoride donor (10) and the heptasaccharide (2) as the acceptor by Cel7B E197A. The XET acceptor substrates were prepared by reductive amination of XGOs with ANTS. The ANTS conjugate of mannose (ManANTS) used as an internal reference for capillary electrophoresis was also prepared by the same procedure. Detailed experimental procedures and product characterization are described in the Supplementary data (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/395/bj3950099add.htm).

HPCE method

Capillary electrophoresis was performed on a Hewlett-Packard HP3D CE G1600 AX system equipped with a diode array UV–Vis detector. The capillary [72 cm effective length, 50 μm internal diameter, fused silica with an extended light path bubble (150 μm) in the detection window] was pretreated or regenerated with 0.1 M NaOH, H2O milliQ, and running buffer (for 30, 10, or 10 min respectively). Samples (ANTS-labelled oligosaccharide standards or enzymatic reaction mixtures) were loaded into the capillary under hydrodynamic injection mode at 40 mbar pressure during a 6 s period. The conditioning between injections consisted of a 5 min equilibration step with running buffer. The running buffer used depended on the electrophoretic method: (i) direct EOF [electro-osmotic flow (cathodic detection)], 50 mM phosphoric acid adjusted to pH 9 with NaOH; (ii) suppressed EOF (cathodic detection), 50 mM phosphoric acid adjusted to pH 2.5 with NaOH; (iii) inverted EOF (anodic detection), 50 mM phosphoric acid adjusted to pH 2.5 with triethylamine. Electrophoresis was performed at −30 kV and a constant temperature of 30 °C. The detector was a UV–Vis diode array and the electropherograms were recorded at 214 nm (20 nm slit), 224 nm (20 nm slit) and 270 nm (20 nm slit). The results of method development and validation are described in the Supplementary data (see Supplementary at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/395/bj3950099add.htm).

PttXET16A reaction monitoring and kinetics

All enzymatic reactions were carried out in 50 mM citrate/50 mM phosphate buffer adjusted to the desired pH with NaOH. Ionic strength was kept constant at I=0.5 M with added KCl. Reactions were performed in a final volume of 100 μl in a temperature regulated bath at the desired temperature. Aliquots (20 μl) were withdrawn at different time intervals, mixed with 20 μl of 2 mM ManANTS in water as an internal reference, the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 10 min in a sealed tube, and finally samples were analysed by HPCE (inverted EOF mode).

With XG-polymer as the donor substrate, the reaction mixtures contained 5 mg/ml XG, 15 mM XGOs-ANTS, and 0.1–0.3 mg/ml PttXET16A enzyme, at pH 5.5 and 30 °C. Reactions using XXXGXXXG (4) as the donor and XXXG-ANTS (12) as the acceptor substrate for reaction monitoring, product characterization, and enzyme standard curve generation were carried out at 1 mM (4), 5 mM (12) and 0.1–1.5 μM enzyme at pH 5.5, 30 °C. For pH studies, the reaction mixtures contained 1 mM (4), 5 mM (12) and 0.3 μM PttXET16A, in the pH range 3–8 at 30 °C. The determination of temperature dependence of enzyme activity was performed at the same substrate and enzyme concentrations at a constant pH 5.5, with temperatures ranging from 10–50 °C.

Product concentration was determined from the electropherograms by the relative peak areas using ManANTS as an internal reference. Initial-rates of product formation (V0 in mM/min) were calculated as the slope of the linear region of the time-course (0–20 min) corresponding to <10% substrate→product conversion.

Studies of steady-state kinetics, varying the donor (4) and acceptor (12) substrate concentrations, were performed at pH 5.5, 30 °C, with donor 0.3–5 mM, acceptor 0.5–10 mM (matrix of 8 donor×8 acceptor concentrations) and 0.3 μM PttXET16A. Kinetic data V0/[E]0=f([donor],[acceptor]) was fitted to modified ping-pong bi-bi kinetic models by non-linear regression analysis using the FigP 2.98 and SigmaPlot 2000 software packages.

RESULTS

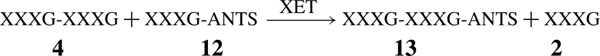

A HPCE method was implemented for activity assays and kinetic characterization of XETs. The method is based on similar assays developed for Leloir glycosyl transferases which use a labelled acceptor bearing a charged chromophore [23–26]. In the present study we used a low-molecular mass XGO as the glycosyl donor, and a labelled heptasaccharide acceptor obtained by reductive amination with ANTS [XXXG-ANTS (12)]. The chosen donor was the tetradecasaccharide XXXGXXXG (4), which is known to act as a glycosyl donor for the mixed-function XET/XEH (XG endohydrolase) from germinated nasturtium seed [11,12]. Under initial-rate assay conditions, PttXET16A catalyses a single transglycosylation reaction to form the labelled product, 13:

|

Synthesis of the tetradecasaccharide donor, XXXGXXXG (4)

Two different strategies to obtain the tetradecasaccharide (4) in a preparative scale were studied. In the first method (Scheme 1A), tamarind seed XG-polymer was incubated with cellulase from T. reesei as essentially described by Fanutti [11], but in such a way that the preparation of mixed monomers (hepta-, octa- and nona-saccharides) and mixed dimers (tetradeca-, pentadeca-, hexadeca-, heptadeca- and octadeca-saccharides) was optimized. After degalactosylation using β-galactosidase from A. niger and purification on a silica gel column, penta- (1), hepta- (2), dodeca- (3) and tetradeca-saccharide (4) were obtained in 14, 23, 7 and 20% yields respectively, and characterized by MS, 1H- and 13C-NMR. For further characterization of compounds 3 and 4, their reducing ends were coupled with 4-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester by reductive amination using the cyanoborohydride procedure, and these derivatives were analysed by LC/MS [27].

To improve the yield of the target tetradecasaccharide, XXXGXXXG (4), a new methodology for the preparation of larger XGOs was developed based on full enzymatic degradation of the XG-polymer down to its repetitive units, chemical activation of the anomeric reducing end, and glycosynthase-catalysed condensation (Schemes 1B and 1C). Tamarind seed XG was first incubated with pure recombinant XG-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase from A. aculeatus [28] until TLC analysis showed only three major spots, then β-galactosidase from A. niger was added to the reaction mixture. At this stage the products of the reaction were acetylated and purified by flash chromatography on silica gel. Acetylated XXG (5) and XXXG (6) were isolated in 14 and 56% yields respectively. Compound 5 was formed by contaminant enzymatic activities found in the commercially available β-galactosidase [29].

Coupling of two XXXG units to produce the target tetradecasaccharide (4) was achieved using glycosynthase technology. Glycosynthases are new enzymes generated by substitution of the catalytic nucleophile by a non-acidic amino acid residue that cannot establish a glycosyl-enzyme intermediate, and therefore leads to hydrolytically inactive enzymes. However, these mutated enzymes can catalyse the transfer of a sugar moiety from an α-glycosyl fluoride (which effectively mimics the glycosyl–enzyme intermediate) to various acceptors [30–32]. We have previously demonstrated that 6II-substituted α-cellobiosyl fluorides are efficient substrates for coupling reactions catalysed by the Cel7B E197A glycosynthase from H. insolens [32]. The scope of this enzyme's function has now been extended to the condensation of the corresponding XG oligosaccharyl α-fluoride (10) with the heptasaccharide (2).

By following Scheme 1(B), standard hydrazine acetate treatment of acetylated XXXG (6) led to selective de-O-acetylation of the anomeric position with an 84% yield. Compound 7 was then subjected to DAST [(diethylamino) sulphur trifluoride] treatment to yield an anomeric mixture of fluorides (8). Anomerization with commercially available pyridine hydrofluoride gave the pure α-fluoride (9), which was isolated in a 68% yield over the course of the two steps. Catalytic de-O-acetylation gave the donor (10) in a quantitative yield. The enzymatic condensation catalysed by the Cel7B E197A mutant was conducted by coupling compounds 10 and 2 using previously described conditions [32]. The dimer XXXGXXXG (4) and the trimer XXXGXXXGXXXG (11) were isolated in 63 and 35% yields respectively.

Synthesis of the ANTS-labelled acceptor (12)

The per-O-acetylated XXXG (6) obtained above, was fully de-O-acetylated by treatment with sodium methoxide in methanol to afford compound 2 in a quantitative yield. It was derivatized by reductive amination with ANTS and sodium cyanoborohydride (Scheme 1B). Preparative-scale production of the ANTS-labelled XXXG (12) required the optimization of a purification protocol consisting of three chromatographic steps: (i) gel filtration chromatography to remove the large excess of unreacted ANTS, (ii) anion exchange chromatography to separate traces of underivatized XXXG, and (iii) a second gel filtration step for desalting and further purification of the final XXXG-ANTS (12). The final product was >95% pure (as assessed by HPCE).

A mixture (1:6:6 molar ratio) of hepta (XXXG)-, octa (XXLG+XLXG)-, and nona (XLLG)-saccharides obtained by endoglucanase hydrolysis of tamarind XG were also ANTS-derivatized to be used as reference compounds in the HPCE method. Likewise, the dimer (4) and the trimer (11) were ANTS-labelled as standards for product characterization when monitoring XET reactions by the HPCE method.

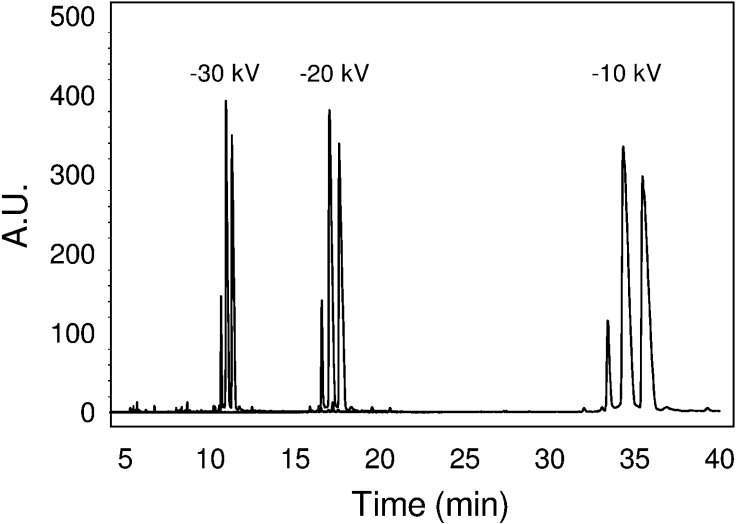

HPCE method development and validation

Electrophoretic conditions were first optimized using a purified mixture of ANTS-labelled XGOs XXXG, (XXLG+XLXG) and XLLG, to evaluate analysis time, resolution and efficacy [33]. Since previous studies with ANTS-labelled low-molecular mass linear oligosaccharides showed that low resolution is attained using basic buffers and direct EOF [26], other conditions were evaluated (see Supplementary material at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/395/bj3950099add.htm). Best results were achieved under inverted EOF using phosphate buffer at pH 2.5 with triethylamine as the EOF modifier. Figure 2 shows the electropherograms obtained at three different voltages (−30, −20 and −10 kV). The final method (fused silica capillary, 50 mM phosphoric acid adjusted to pH 2.5 with triethylamine, −30 kV and hydrodynamic injection) had a linear response between 0.01 and 1 mM XXXG-ANTS, and repeatability with variation coefficients of less that 5% within all of the concentration range.

Figure 2. Electropherograms at different voltage.

The sample analysed is a mixture of ANTS-labelled XGOs [XXXG-ANTS: (XXLG-ANTS+XLXG-ANTS): XLLG-ANTS 1:6:6]. A.U., absorbance units.

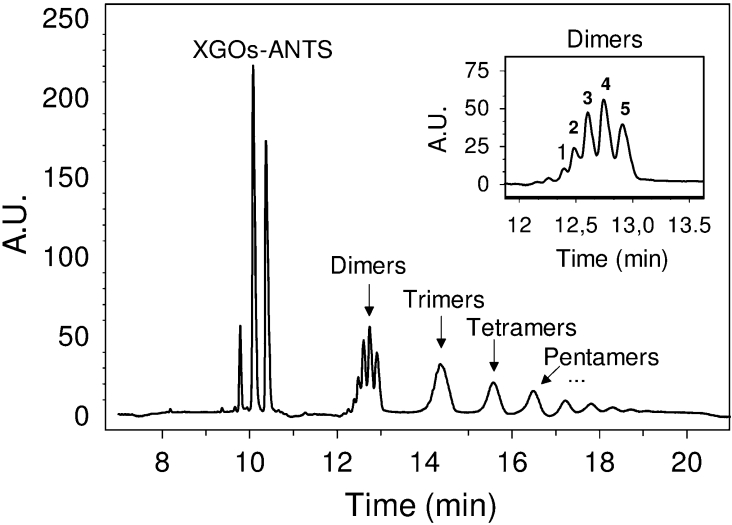

PttXET16A reaction monitoring and product identification

First, polymeric XG was used as the donor and a mixture of ANTS-labelled XGOs as the acceptor. The enzymatic reaction was analysed to monitor reaction progress and detect product formation (Figure 3). Several peak clusters were observed in the electropherogram corresponding to dimers, trimers and tetramers etc. They result from transfer of the basic units of XG polymer (XXXG, XXLG, XLXG and XLLG), all generated after extensive depolymerization of the XG donor, to the XGO-ANTS acceptors. Theoretically, 16 different dimers (4 donors×4 acceptors) can be produced, with 5 unique molecular masses. Indeed, exactly 5 peaks are precisely detected in the dimer cluster on the electropherogram. This demonstrates that the XGO-ANTS are good acceptors, and that the HPCE method has enough resolution to monitor XET activity. However, the polydisperse nature of the donor XG, together with the multiple catalytic events occurring before the end products are obtained, limits this experimental approach for enzymological studies of XET action.

Figure 3. HPCE analysis of the PttXET16A-catalysed transglycosylation using XG-polymer as the donor and a mixture of XGOs-ANTS as acceptor substrates.

Inset: magnification of the dimer region in which 5 peaks are resolved (see Results section). A.U., absorbance units.

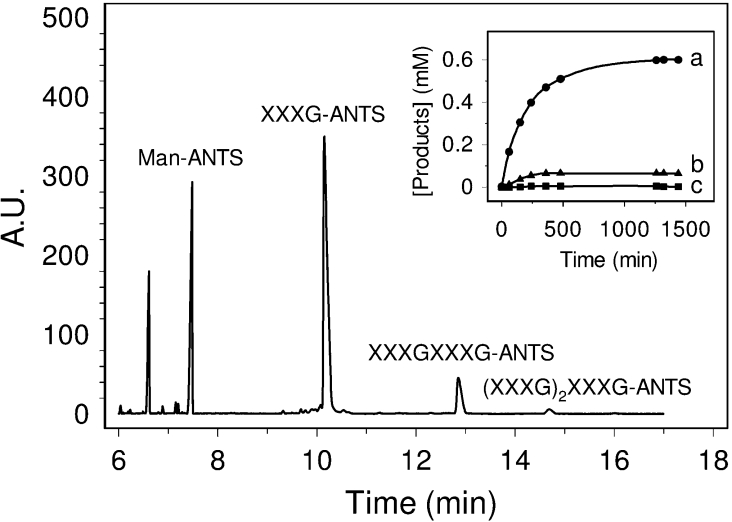

The tetradecasaccharide (4) was assayed as a low-molecular-mass donor for the transglycosylation reaction catalysed by PttXET16A using purified XXXG-ANTS (12) as the acceptor substrate. HPCE (Figure 4) shows the formation of a dimer, a trimer and traces of a tetramer. The dimer and trimer were identified as XXXGXXXG-ANTS and (XXXG)2XXXG-ANTS respectively, by co-injection with chemically synthesized standards. The dimer is the initial product formed by transfer of the non-reductive repeating unit from donor 4 to the acceptor (Figure 4, inset), whereas larger oligomers (minor products) arise from transglycosylation of donor 4 to the initially formed product acting as an acceptor.

Figure 4. HPCE analysis of the transglycosylation reaction between the 1 mM XXXGXXXG (4) donor and the 5 mM XXXG-ANTS (12) acceptor catalysed by PttXET16A at pH 5.5, 30 °C.

ManANTS is the internal reference for peak area integration. Inset: time course of the reaction. (a) XXXGXXXG-ANTS; (b) (XXXG)2XXXG-ANTS; (c) (XXXG)3XXXG-ANTS. A.U., absorbance units.

PttXET16A enzyme characterization

Kinetic studies were performed in citrate/phosphate buffer at constant ionic strength with tetradecasaccharide 4 and ANTS-labelled compound 12 as the donor and acceptor substrates respectively. As described in the Materials and methods section, initial rates are determined as the slope of the linear region of the time-course (product concentration versus reaction-time) corresponding to <10% conversion.

Initial-rates linearly increased with enzyme concentration in all the concentration ranges studied (0–1.5 μM). Reactions were carried out at pH 5.5 and 30 °C using 1 mM donor 4 and 5 mM acceptor 12. Addition of BSA or modification of the buffer concentration (in the range 25–100 mM) did not affect enzyme activity or stability (results not shown).

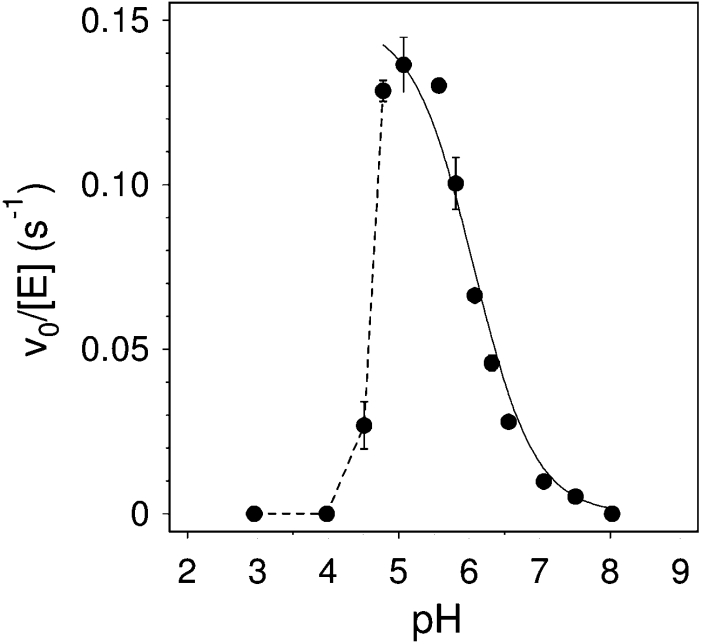

The pH-dependence of enzyme activity (Figure 5) was analysed at 30 °C using 1 mM donor and 5 mM acceptor. Maximum activity was between pH 5.0 and 5.5. Activity follows a single ionization curve at high pHs. Data from pH 5–8 were fitted to equation (1):

|

(1) |

with a kinetic pKa of 6.1±0.1 corresponding to general acid catalysis. At lower pHs, a rapid loss of activity is clearly observed. Enzyme inactivation at pH<5 has previously been observed for PttXET16A using standard assays [21], and appears to be a common feature of XETs with pH optima between 5 and 7 [8,13,34–38].

Figure 5. pH-dependence of PttXET16A activity at 30 °C, 1 mM donor 4 and 5 mM acceptor 12.

The solid line is the fitted curve of the data from pH 5–8 to equation 1. The dashed line traces the enzyme inactivation at pH<5.

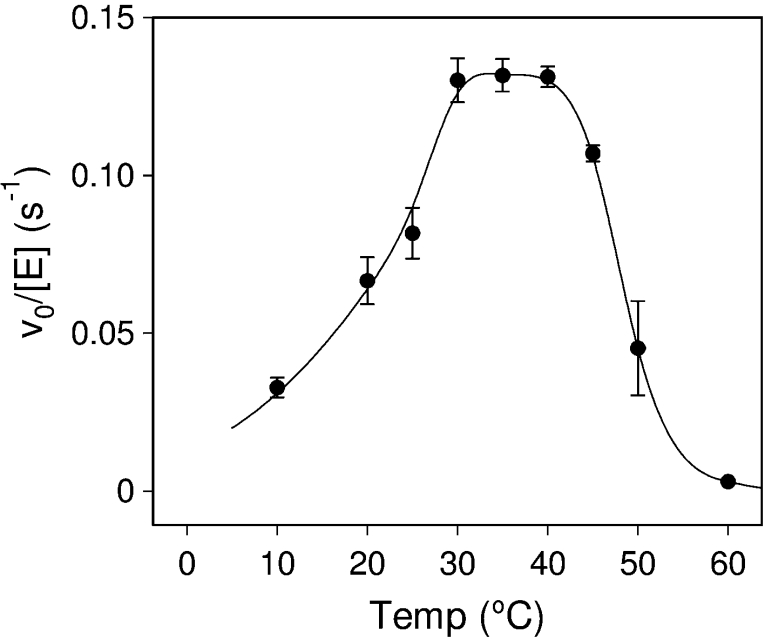

The temperature dependence of PttXET16A (Figure 6) was evaluated at pH 5.5. Maximum activity was obtained between 30 and 40 °C, followed by a rapid inactivation at higher temperatures as previously observed using standard assays [21]. Similar behaviour has been reported for XET from cauliflower [36,37].

Figure 6. Temperature dependence of PttXET16A activity at pH 5.5, 1 mM donor 4 and 5 mM acceptor 12.

Steady state kinetic parameters

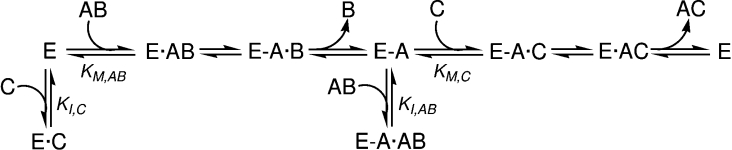

With the defined low-molecular-mass oligosaccharide donor and acceptor substrates, a single transglycosylation event is observed under initial-rate conditions. Steady-state kinetics varying both the donor (0.2–5 mM) and acceptor (0.5–10 mM) concentrations were performed at pH 5.5 and 30 °C. Initial rates were analysed according to different variants of ping-pong mechanisms [39]. Best results were obtained when fitting the data to equation (2), which describes a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism with competitive inhibition by the labelled acceptor on binding to the free enzyme, and inhibition by the donor substate on binding to the acceptor subsites of the enzyme (Scheme 2):

|

(2) |

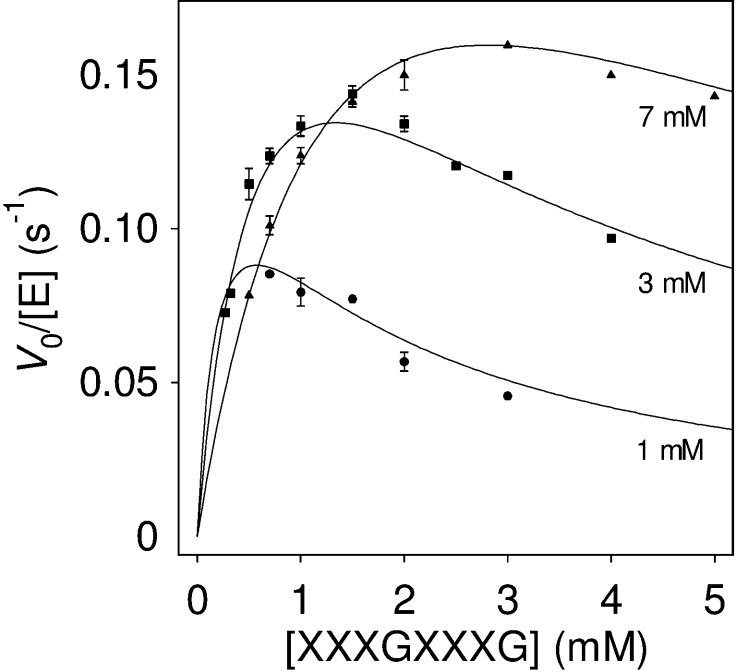

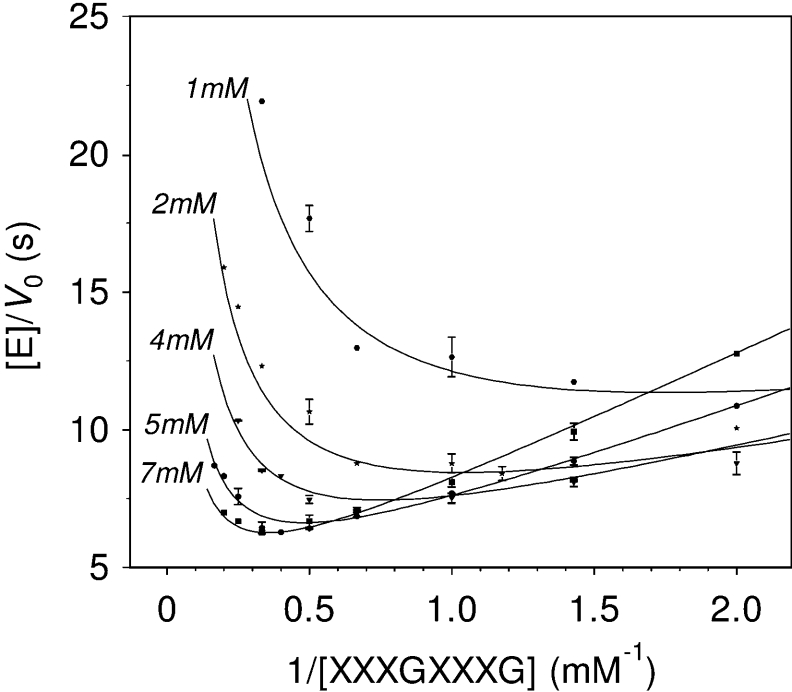

where AB is the donor; C, the acceptor; Km,AB, the Km for the donor; Km,C, the Km for the acceptor; Ki,AB, the inhibition constant for the donor; and Ki,C, the inhibition constant for the acceptor. Figure 7 presents selected kinetics, varying the donor concentration at fixed acceptor concentrations. As shown in the double-reciprocal plots (Figure 8), a good fit is obtained with the following kinetic parameters: kcat=0.45±0.04 s−1, Km,AB=0.37±0.09 mM, Km,C=1.9±0.3 mM, Ki,AB=1.0±0.1 mM, and Ki,C=1.5±0.4 mM.

Scheme 2. Proposed kinetic mechanism for the reaction of PttXET16A.

AB, donor substrate; C, acceptor substrate.

Figure 7. Kinetics (V0 versus [donor 4]) at different acceptor 12 concentrations.

Initial rates (V0) were determined by the HPCE method at pH 5.5, 30 °C. Only data at selected (1, 3 and 7 mM) acceptor concentrations are presented. Plotted lines are the corresponding calculated curves obtained after fitting all kinetic data (8 donor×8 acceptor concentrations) to equation (2).

Figure 8. Double-reciprocal plot for kinetics of PttXET16A using compounds 4 and 12 as the donor and acceptor substrate respectively.

Reactions were performed in citrate/phosphate buffer pH 5.5, 30 °C, and initial rates determined by the HPCE method. Data 1/V0 versus 1/[donor] are plotted at different fixed acceptor concentrations (indicated in the Figure).

DISCUSSION

Current activity assays for XETs based on XG as the donor substrate present evident drawbacks for detailed kinetic studies due to the polymeric and polydisperse nature of the substrate. To overcome this limitation, a synthetically prepared tetradecasaccharide has been shown to act as a donor substrate for PttXET16A, and a new assay based on HPCE using a tagged acceptor has been developed.

Structural analysis has shown that a wide range of polysaccharide hydrolases and transglycosylases, including PttXET16A [20], contain up to 10 sugar-binding subsites in their active site clefts. It has been generally observed that short oligosaccharides act as substrates provided that critical catalytic subsites are occupied, although few previous studies have analysed the ability of low-molecular-mass XGOs to act as glycosyl donors for XET. TLC and HPLC analyses have shown that the compounds XXXGXXXG and GXXGXXXG undergo hydrolysis and transglycosylation (the latter in the presence of the nonasaccharide acceptor, XLLG) by a mixed function XG endotransglycosylase/endohydrolase from germinated nasturtium seeds [11,12]. However, no quantitative data have yet been determined for any XET.

Because preparation of pure tetradecasaccharide (XXXGXXXG, 4) by controlled enzymatic hydrolysis of XG is tedious, requiring precise control of reaction parameters and lengthy purification steps, a procedure using glycosynthase technology has been developed. In this way, condensation of the α-heptasaccharyl fluoride (10) with the free heptasaccharide (2), catalysed by the Cel7B E197A glycosynthase, gave the target tetradecasaccharide (4) in a 63% yield. The calculated overall yield from XG, 20%, is similar to that obtained by enzymatic hydrolysis, but the glycosynthase procedure is more reproducible and readily scales up.

The chemical synthesis of the ANTS-labelled acceptor (12) has been optimized, requiring careful purification over three consecutive chromatographic steps. Although widely used on an analytical scale, ANTS-saccharide conjugates have not, to our knowledge, been produced in a preparative scale. The present method allows routine preparation of XXXG-ANTS on a gram scale. Other labelled oligosaccharides with neutral or weakly acidic fluorescent tags have been shown to act as suitable acceptor substrates (with XG as the donor) for in vitro assays [14,17] or in vivo localization of XET activity in plant cell walls [40–42]. Here, the highly charged ANTS label on the reduced heptasaccharide is also a good acceptor, indicating that the acidic tag does not prevent binding to the acceptor subsites of the enzyme. This is consistent with the demonstration of the three-dimensional-structure of non-covalent PttXET16A–XLLG and PttXET16A–XLLG-CNP complexes, in which the ligands were bound to the acceptor subsites of the binding cleft with the first glucosyl unit on the reducing ends hanging outside the binding cleft [20].

Kinetic parameters using XG as the donor substrate have been reported for XET activity in extracts from suspension-cultured poplar cells [43]. An ordered bi-bi reaction mechanism was proposed, in which both XG as the glycosyl donor and XGO as the glycosyl acceptor associate with the enzyme to form a ternary complex before cleavage of the XG and transglycosylation to the acceptor occurs. However, the original mechanism postulated for XET involves a double displacement mechanism with formation of a glycosyl–enzyme intermediate [7]. This is in keeping with the observed mechanism of GH16 hydrolases [44,45] and the mechanism of retaining glycoside hydrolases in general [46] (except GH4 enzymes for which a redox mechanism has been recently reported [47]). The double displacement mechanism was supported by the observation that XET from nasturtium seeds is able to form a relatively stable intermediary complex with XG from which the enzyme can be released when using a suitable glycosyl acceptor or imidazole as the exogenous nucleophile [48]. Farkaš and co-workers [49] also analysed the kinetics of nasturtium seed XET obtained when using XG as the donor and radio-labelled 3H-XGOol (reduced XGO) acceptors by fitting the data to modified ping-pong bi-bi mechanism models. They concluded that the best model explaining the experimental data was a “modified ping-pong mechanism with oligosaccharides acting as dead-end inhibitors and with two alternative fates for the glycosyl–enzyme intermediate: either hydrolysis or transglycosylation” [49]. However, all previous studies provide apparent kinetic parameters and fail to find an ideal model because of the molecular heterogeneity of the XG donor, the multiple turnovers taking place with the polymeric XG substrate, and the undetectable transfer reactions to other XG-polymer molecules as the acceptor.

The present HPCE assay allows the kinetic characterization of PttXET16A under initial-rate conditions in which a single transglycosylation event occurs when using defined low-molecular mass donors. PttXET16A has no detectable XGase (hydrolytic) activity (EC 3.2.1.151) under standard conditions [21]. Steady-state kinetics using compounds 4 and 12 as the donor and acceptor substrates respectively, do not fit an ordered bi-bi mechanism as initially proposed for a XET from poplar cells [43]. But they are well described by a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism with competitive inhibition by the acceptor substrate on binding to the free enzyme, and inhibition by the donor substrate on binding to the acceptor subsites of the intermediate complex (Scheme 2). This model is similar to that proposed by Farkaŝ and co-workers for the nasturtium enzyme [49], except that donor inhibition is included and hydrolysis of the glycosyl–enzyme intermediate is omitted. However, strong donor inhibition is apparent at low acceptor concentrations (i.e. 1 mM, Figure 7) that result in a deviation from the model (Scheme 2, Equation 2). The fitted curve in Figure 8 at 1 mM acceptor concentration exemplifies this trend. It is probable that when the donor acts as the inhibitor, an undetected polymerization reaction occurs (the product is not ANTS-labelled), which may explain the unusually strong inhibitory effect of the donor. The model incorporating donor polymerization was too complex to be adjusted to the experimental data, but this side reaction can explain the deviations observed at high donor/acceptor concentration ratios.

In summary, the HPCE method has proven to be appropriate for XET activity assays using a low-molecular-mass donor, and therefore is the method of choice to screen different donor substrates. The method can be directly applied to perform detailed subsite mapping analysis of the enzyme's binding cleft and to define the substrate specificity of XET enzymes. PttXET16A follows a ping-pong bi-bi kinetic mechanism with donor and acceptor inhibition as determined for the enzyme-catalysed transglycosylation of substrates 4 and 12. However, donor self-transglycosylation, which is not detected in this assay, may explain the observed deviations from the fitted model at low acceptor concentrations (≤1 mM). To prevent this putative side reaction and to obtain a simpler kinetic mechanism with improved fit to the experimental data, a donor that is ‘blocked’ on its non-reducing end is required. Work is in progress to synthesize novel compounds for such analysis; their application in this versatile assay will be reported in due course.

Online data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EU contract QLK5-CT-2001-00443. Grants 2001SGR 00327 from Generalitat de Catalunya and CNRS are also acknowledged. K. P. acknowledges a Marie Curie fellowship.

References

- 1.Carpita N. C., Gibeaut D. M. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishitani K. The role of endoxyloglucan transferase in the organization of plant cell walls. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997;173:157–206. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincken J. P., York W. S., Beldman G., Voragen A. G. J. Two general branching patterns of xyloglucan, XXXG and XXGG. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:9–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiter W. D. Biosynthesis and properties of the plant cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:536–542. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishitani K. Construction and restructuring of the cellulose-xyloglucan framework in the apoplast as mediated by the xyloglucan-related protein family. A hypothetical scheme. J. Plant Res. 1998;111:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B. Carbohydrate-active enzymes: an integrated database approach. In: Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J., Henrissat B., Svensson B., editors. Recent Advances in Carbohydrate Bioengineering. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1999. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farkaš V., Sulová Z., Stratilova E., Hanna R., Maclachlan G. Cleavage of xyloglucan by nasturtium seed xyloglucanase and transglycosylation to xyloglucan subunit oligosaccharides. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;298:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90423-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fry S. C., Smith R. C., Renwick K. F., Martin D. J., Hodge S. K., Matthews K. J. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase, a new wall-loosening enzyme activity from plants. Biochem. J. 1992;282:821–828. doi: 10.1042/bj2820821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishitani K., Tominaga R. Endo-xyloglucan transferase, a novel class of glycosyltransferase that catalyzes transfer of a segment of xyloglucan molecule to another xyloglucan molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:21058–21064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose J. K. C., Braam J., Fry S. C., Nishitani K. The XTH family of enzymes involved in xyloglucan endotransglucosylation and endohydrolysis: current perspectives and a new unifying nomenclature. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:1421–1435. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanutti C., Gidley M. J., Reid J. S. G. Action of a pure xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase (formerly called xyloglucan-specific endo-(1→4)-β-D-glucanase) from the cotyledons of germinated nasturtium seeds. Plant J. 1993;3:691–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.03050691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanutti C., Gidley M. J., Reid J. S. G. Substrate subsite recognition of the xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase or xyloglucan-specific endo-(1→4)-β-D-glucanase from the cotyledons of germinated nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus) seeds. Planta. 1996;200:221–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00208312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell R., Braam J. In vitro activities of four xyloglucan endotransglycosylases from Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1999;18:371–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishitani K. A novel method for detection of endo-xyloglucan transferase. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;33:1159–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maclachlan G., Brady C. Endo-1,4-β-glucanase, xyloglucanase, and xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase activities versus potential substrates in ripening tomatoes. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:965–974. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulová Z., Lednicka M., Farkaš V. A colorimetric assay for xyloglucan-endotransglycosylase from germinating seeds. Anal. Biochem. 1995;229:80–85. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fry S. C. Novel ‘dot-blot’ assays for glycosyltransferases and glycosylhydrolases: optimization for xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) activity. Plant J. 1997;11:1141–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Rassi Z. Totowa, NJ, U.S.A.: Humana Press; 2003. Capillary Electrophoresis of Carbohydrates. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulus A., Klockow A. Detection of carbohydrates in capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A. 1996;720:353–376. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00323-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson P., Brumer H., III, Baumann M. J., Kallas A. M., Henriksson H., Denman S. E., Teeri T. T., Jones T. A. Crystal structures of a poplar xyloglucan endotransglycosylase reveal details of transglycosylation acceptor binding. Plant Cell. 2004;16:874–886. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallas A. M., Piens K., Denman S., Henriksson H., Fäldt E. J., Johansson P., Brumer H., III, Teeri T. T. Enzymatic properties of native and deglycosylated hybrid aspen xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 16A expressed in Pichia pastoris. Biochem. J. 2005;390:105–113. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill S. C., van Hippel P. H. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K. B., Desai U. R., Palcic M. M., Hindsgaul O., Linhardt R. J. An electrophoresis-based assay for glycosyltransferase activity. Anal. Biochem. 1992;205:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90586-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le X. C., Zhang Y., Dovichi N. J., Compston C. A., Palcic M. M., Beever R. J., Hindsgaul O. Study of the enzymic transformation of fluorescently labeled oligosaccharides in human epidermoid cells using capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. 1997;781:515–522. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sujino K., Uchiyama T., Hindsgaul O., Seto N. O., Wakarchuk W. W., Palcic M. M. Enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharide analogues: evaluation of UDP-Gal analogues as donors for three retaining α-galactosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monegal A., Pinyol R., Planas A. Capillary electrophoresis method for the enzymatic assay of galactosyltransferases with post-reaction derivatization. Anal. Biochem. 2005;346:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D. T., Her G. R. Structural analysis of chromophore-labeled disaccharides and oligosaccharides by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 1998;33:644–652. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199807)33:7<644::AID-JMS667>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pauly M., Andersen L. N., Kauppinen S., Kofod L. V., York W. S., Albersheim P., Darvill A. A xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase from Aspergillus aculeatus: expression cloning in yeast, purification and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Glycobiology. 1999;9:93–100. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.York W. S., Harvey L. K., Guillen R., Albersheim P., Darvill A. G. The structure of plant cell walls. XXXVI. Structural analysis of tamarind seed xyloglucan oligosaccharides using β-galactosidase digestion and spectroscopic methods. Carbohydr. Res. 1993;248:285–301. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84135-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackenzie L. F., Wang Q., Warren R. A. J., Withers S. G. Glycosynthases: mutant glycosidases for oligosaccharide synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5583–5584. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malet C., Planas A. From β-glucanase to β-glucansynthase: glycosyl transfer to α-glycosyl fluorides catalyzed by a mutant endoglucanase lacking its catalytic nucleophile. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:208–212. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fort S., Boyer V., Greffe L., Davies G. J., Moroz O., Christiansen L., Schülein M., Cottaz S., Driguez H. Highly efficient synthesis of β(1,4)-oligo- and polysaccharides using a mutant cellulase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5429–5437. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiesa C., Horvath C. Capillary zone electrophoresis of malto-oligosaccharides derivatized with 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid. J. Chromatogr. 1993;645:337–352. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)83394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purugganan M. M., Braam J., Fry S. C. The Arabidopsis TCH4 xyloglucan endotransglycosylase. Substrate specificity, pH optimum, and cold tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:181–190. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schröder R., Atkinson R. G., Langenkamper G., Redgwell R. J. Biochemical and molecular characterisation of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase from ripe kiwifruit. Planta. 1998;204:242–251. doi: 10.1007/s004250050253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steele N. M., Fry S. C. Differences in catalytic properties between native isoenzymes of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) Phytochemistry. 2000;54:667–680. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henriksson H., Denman S. E., Campuzano I. D. G., Ademark P., Master E. R., Teeri T. T., Brumer H., III N-linked glycosylation of native and recombinant cauliflower xyloglucan endotransglycosylase 16A. Biochem. J. 2003;375:61–73. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulová Z., Baran R., Farkaš V. Divergent modes of action on xyloglucan of two isoenzymes of xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase from Tropaeolum majus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2003;41:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segel I. H. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1975. Enzyme Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito H., Nishitani K. Visualization of EXGT-mediated molecular grafting activity by means of a fluorescent-labeled xyloglucan oligomer. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999;40:1172–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vissenberg K., Martinez-Vilchez I. M., Verbelen J. P., Miller J. G., Fry S. C. In vivo colocalization of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase activity and its donor substrate in the elongation zone of Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1229–1237. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourquin V., Nishikubo N., Abe H., Brumer H., Denman S., Eklund M., Christiernin M., Teeri T. T., Sundberg B., Mellerowicz E. J. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylases have a function during the formation of secondary cell walls of vascular tissues. Plant Cell. 2002;14:3073–3088. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeda T., Mitsuishi Y., Sakai F., Hayashi T. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylation in suspension-cultured poplar cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996;60:1950–1955. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Planas A. Bacterial 1,3–1,4-β-glucanases: structure, function and protein engineering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1543:361–382. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viladot J. L., Canals F., Batllori X., Planas A. Long-lived glycosyl-enzyme intermediate mimic produced by formate re-activation of a mutant endoglucanase lacking its catalytic nucleophile. Biochem. J. 2001;355:79–86. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies G., Sinnott M. L., Withers S. G. Glycosyl Transfer in Comprehensive Biological Catalysis. In: Sinnott M. L., editor. London: Academic Press Ltd; 1998. pp. 119–209. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yip V. L. Y., Varrot A., Davies G. J., Rajan S. S., Yang X., Thompson J., Anderson W. F., Withers S. G. An unusual mechanism of glycoside hydrolysis involving redox and elimination steps by a family 4 β-glycosidase from Thermotoga maritima. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8354–8355. doi: 10.1021/ja047632w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sulová Z., Takacova M., Steele N. M., Fry S. C., Farkaš V. Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase: evidence for the existence of a relatively stable glycosyl-enzyme intermediate. Biochem. J. 1998;330:1475–1480. doi: 10.1042/bj3301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baran R., Sulová Z., Stratilova E., Farkaš V. Ping-pong character of nasturtium-seed xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET) reaction. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2000;19:427–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.