Abstract

Crystal structures of bacterial CLC (voltage-gated chloride channel family) proteins suggest the arrangement of permeation pores and possible gates in the transmembrane region of eukaryotic CLC channels. For the extensive cytoplasmic tails of eukaryotic CLC family members, however, there are no equivalent structural predictions. Truncations of cytoplasmic tails in different places or point mutations result in loss of function or altered gating of several members of the CLC family, suggesting functional importance. In the present study, we show that deletion of the terminal 100 amino acids (N889X) in human ClC-1 (skeletal-muscle chloride channel) has minor consequences, whereas truncation by 110 or more amino acids (from Q879X) destroys channel function. Use of the split channel strategy, co-injecting mRNAs and expressing various complementary constructs in Xenopus oocytes, confirms the importance of the Gln879–Arg888 sequence. A split between the two CBS (cystathionine β-synthase) domains (CBS1 and CBS2) gives normal function (e.g. G721X plus its complement), whereas a partial complementation, eliminating the CBS1 domain, eliminates function. Surprisingly, function is retained even when the region Gly721–Ala862 (between CBS1 and CBS2, and including most of the CBS2 domain) is omitted from the complementation. Furthermore, even shorter peptides from the CBS2-immediate post-CBS2 region are sufficient for functional complementation. We have found that just 26 amino acids from Leu863 to Arg888 are necessary since channel function is restored by co-expressing this peptide with the otherwise inactive truncation, G721X.

Keywords: carboxyl tail fragment, CBS domain, electrophysiology, human skeletal-muscle chloride channel (hCIC-1), myotonia, truncation

Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; CLC, voltage-gated chloride channel family; ClC-1, skeletal-muscle chloride channel; hClC-1, human ClC-1; rClC-1, rat ClC-1; IMPDH, inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase; WT, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

Chloride ion flow, mainly through ClC-1 (skeletal-muscle chloride channel) channels, contributes 70–85% of the total membrane conductance under resting conditions in skeletal muscle [1,2]. Myotonic muscle diseases are then caused by decreased chloride conductance due to mutations in the CLCN1 gene [3,4] or to decreased expression of ClC-1 [5]. X-ray crystallographic studies of the CLC (voltage-gated chloride channel family) proteins from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (StClC) and Escherichia coli (EcClC) have revealed the general membrane-resident structure of the CLC family of chloride channels [6]. Clearly illustrated transmembrane domains and a dimeric arrangement of protein subunits clearly demonstrate the long-predicted double-barrelled nature of the channel. There is no similar structural information for the long cytoplasmic carboxyl tails that are so characteristic of the eukaryotic CLCs. For example, the carboxyl tail of hClC-1 (human ClC-1) contains more than 400 amino acids, approx. 40% of the total protein. It has commonly been proposed that these extensive tails in the ‘muscle-type’ CLCs (ClC-0 and ClC-1) are involved in translation and translocation to the plasma membrane [7–10], although this is also disputed [11]. Whether or not they are essential for membrane insertion, there is little doubt that they have an influence on channel gating [8–13], perhaps as a result of their long-range influence on an externally accessible chloride-binding site near the channel gate [13]. Alternatively, some definable part or parts of the carboxyl tail might influence gating by close, non-covalent association with cytoplasmic loops or helices of the membrane-resident domain [9].

Two CBS (cystathionine β-synthase) domains of approx. 45–50 amino acids (each composed of two α-helical and three β-strand segments in order, β1α1β2β3α2) are present within the carboxyl tails of all eukaryotic CLCs [7] and many other proteins [14]. Whether CBS1 and CBS2 interact, and what function this might serve, has been the subject of ongoing research [7,10,11,14–16].

Several split channel co-expression studies have shown that if a cut is made between the two CBS domains, full functional complementation is seen in both ClC-0 and ClC-1 [7,8,10,11], but if the cut in the tail occurs before the first CBS domain (CBS1), or within it, there is no functional reconstitution. In apparent confirmation of the importance of CBS1, a study with yeast CLC (Gef1p) [17] showed mutations in this region to be deleterious. Estévez et al. [10] produced in-frame deletions of CBS1 in full-length hClC-1 and in split channel co-expressions. As none of these were functional, an essential requirement for CBS1 is indicated. In contrast, the findings of Hebeisen et al. [11] would suggest otherwise. These authors report totally deleting CBS1, in addition to extended lengths of the CBS1–CBS2 interdomain linker, with little functional consequence.

In rClC-1 (rat ClC-1), deletion of the, formerly designated, D13 hydrophobic region [18] that occupies the larger part of the second CBS domain (CBS2) caused some change in channel behaviour, but did not destroy function [9]. It has since been confirmed that in-frame deletion of the whole of CBS2 from hClC-1 is compatible with the maintenance of channel activity [10]. On the other hand, Hebeisen et al. [11] found that they could only retain function in hClC-1 with CBS2 deleted, if CBS2 were replaced by CBS1. By using alanine scanning, Schwappach et al. [17] also found a stretch of 25 amino acids occurring within CBS2 that seemed to be functionally important.

Previous work from our laboratory showed that removal of the final 100 amino acids of rClC-1 did not significantly affect channel function, whereas deletion of 125 amino acids (L869X, equivalent to L863X in hClC-1) completely eliminated chloride currents [9]. Others have obtained similar results in both ClC-0 and ClC-1. Sequence post-CBS2 seems largely dispensable [8,11,12] when compared with truncations within and before CBS2 which show no chloride channel activity. In hClC-1, seven myotonia-causing truncations have been identified within the carboxyl tail [4]. Of these naturally occurring truncations, four [Q658X, E717X, Q807X and c.2264delC (‘c.’ stands for cDNA numbering with ‘1’ corresponding to the alanine of the ATG translation initiation codon; this accords with the rules of the Human Genome Variation Society at http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/) introducing a frame shift following Gln754] are located before CBS2 and are clinically presented as recessive type myotonia. Two others (c.2152insCTCA and c.2518–2519del) occur in CBS2, introduce frame shifts after Tyr837 and Tyr839 and are associated with dominant and recessive myotonia respectively. Loss of the final 95 amino acids, in the R894X truncation, seems to give rise to the dominant disease in some families and the recessive condition in others [19–23].

In the present study, we aimed to learn more about the essential regions of the hClC-1 carboxyl tail and used the split channel strategy to express different truncation mutants and co-express carboxyl tail constructs making overlapping and exactly or partly complementary pairs in Xenopus oocytes. We were particularly interested in determining the effects of our carboxyl tail manipulations on gating, especially common gating.

We have thus extended previous research on ClC-0, ClC-1 and ClC-5 which showed that co-expressed channel portions split between CBS1 and CBS2 are functional [7,10,11,24]. We have also added to prior knowledge of those portions of the interdomain linker [10,11], of CBS2 [9,10] and of the post-CBS2 sequence [8–12] that can be absent without compromising function.

Our voltage clamp results revealed that: (i) the region from Gly721 to Ala862 (after CBS1 and including 4/5 of the CBS2) can be absent, but the channel remains functional; (ii) the terminal 100 amino acids can simultaneously be absent, allowing channel function to be restored to the inactive truncation mutant, N1–720, by co-expressing it with a minimal 26-amino-acid carboxyl tail peptide (Leu863–Asn888); and (iii) systematic deletions, coexpressions and alanine scans led us to confirm the importance of Glu865 in allowing closure of the common gate.

EXPERIMENTAL

Generation of mutant constructs in the carboxyl tail region of hClC-1

All DNA constructs were generated using the QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.). The strategy of primer design was in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Transmembrane region constructs with carboxyl tail truncations N1–600, N1–720, N1–862, N1–868, N1–871, N1–878, N1–885 and N1–888 were produced by introducing a stop codon at the appropriate numbered location (e.g. at Tyr601, Gly721 and, as shown in Figure 1, Leu863 etc.) in hClC-1 in the plasmid pTLN (pTLN is the Xenopus oocyte expression vector, which was modified by Lorenz et al. [25]). The C-terminal peptides C721–988, C863–988, C869–988, C872–988, C879–988, C886–988 and C889–988 were generated as follows: an NcoI site, Met and Glu (the initial two amino acids in hClC-1) were first introduced into WT (wild-type) hClC-1 immediately before each truncation site and the resultant mutant construct was digested with the restriction enzyme NcoI. Each appropriate DNA fragment was then isolated and ligated back into pTLN, thus producing cDNA constructs for the C-terminal peptides, as listed, but with Met and Glu preceding the indicated truncation site (e.g. C721–988 predicts expression of peptide MEG721K722S723…L988, where the residue numbers relate to WT hClC-1) (Figure 2). Short cDNAs coding for peptides Leu863–Arg888 and Leu863–Pro900 were generated from the C-terminal peptide, C863–988, by introducing stop codons at Asn889 and Pro901 respectively (Figures 1 and 2). Mutations E864A, E865A, L866A, Q867A and K868A were introduced into the C-terminal peptide C721–988 by changing the numbered amino acids to alanine either singly or in various combinations. The veracity of all newly generated DNA constructs was confirmed by sequencing. Template DNA was prepared as described previously [26] and the SP6 mMessage mMachine™ kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.) was used for RNA transcription.

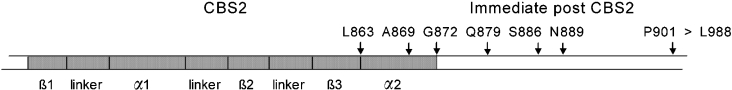

Figure 1. Region of hClC-1 at and immediately beyond CBS2.

Part of the C-terminal of hClC-1, from about Asp822 to Pro901 (not to scale), showing the organization of the CBS2 domain (shaded, three β-strands and two α-helices) and the immediate post-CBS2 region. Arrows indicate the approximate positions in this sequence at which truncations, or constructs for co-expression, were made.

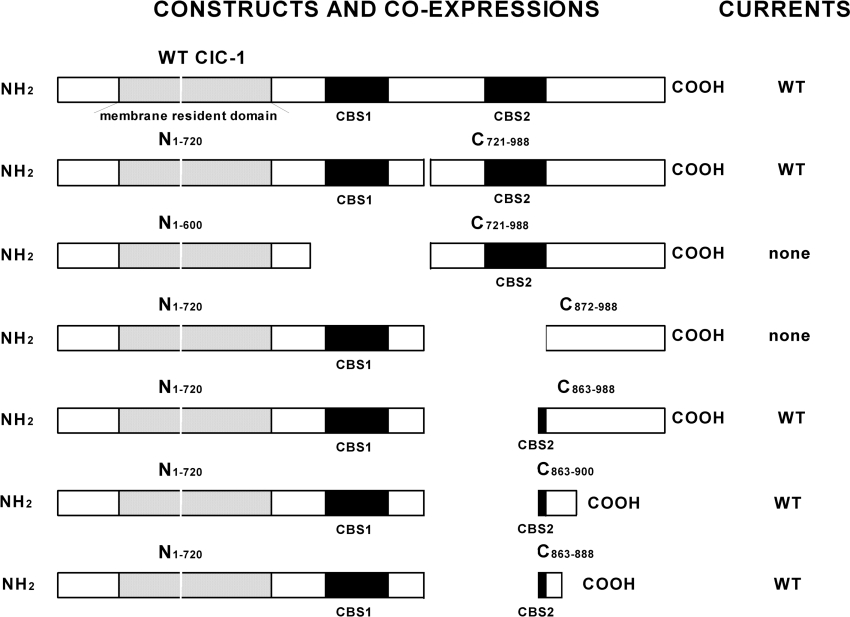

Figure 2. Short carboxyl tail fragments of hClC-1 co-expressed with membrane-resident constructs allow WT currents.

Some of the most informative of our hClC-1 constructs and co-expressions are illustrated as bars. These show the approximate positions of various protein domains, and most importantly for our study, the overall organization of the carboxyl tail. The membrane-resident domain of hClC-1 is shown shaded and two CBS domains are shown in black (not to scale). Currents obtained by two-electrode voltage clamp are described in the column at the right of the Figure.

Electrophysiology – two-electrode voltage clamp

RNA (20 ng) was injected into Xenopus oocytes alone, or 20 ng of RNA coding for a C-terminal truncation was co-injected with 20 ng of RNA coding for an N-terminal truncation or for an N-terminal truncation short peptide. Oocytes were incubated in modified Barth's solution: 88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.82 mM MgSO4 and 10 mM Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.5 with NaOH) at 17 °C. After 24–72 h of incubation, chloride currents were measured at room temperature (21–23 °C) in ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM Hepes at pH 7.4) [7] with an NPI® Turbo TEC amplifier (ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY, U.S.A.). It might be argued that our functionally complementing channels are merely the product of read-through of truncations such as the N1–720 construct. On no occasion, however, have we seen evidence of functional channels in oocytes expressing N1–720 alone or N1–720 plus partial complements beginning more distal than Leu863. Borosilicate glass electrodes had 0.3–1.0 MΩ resistance when filled with an internal solution of 3 M KCl. Currents were recorded in response to 200 ms voltage steps, from +100 to −140 mV, at 20 mV intervals, after a 200 ms prepulse at +40 mV (to open gates). The holding potential was −30 mV [27]. Data were collected from at least three separate batches of oocytes with n≥6, and analysed using pCLAMP 6.0 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.).

Data analysis

To estimate peak tail current and extract the time constants of current relaxation, raw hClC-1 deactivating currents were fitted with an equation of the form:

|

(1) |

where A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the fast and common (slow) exponential components, τ1 and τ2 are their time constants, C is the amplitude of the steady-state component and t is time.

Normalized peak tail currents for voltage steps to −100 mV after test pulses between −140 and 100 mV were used to produce apparent open probability (Po) curves. Data points obtained in this way were fitted by a Boltzmann distribution with an offset to obtain Po curves:

|

(2) |

as described previously [27–30], where Pmin is an offset, or minimum Po at very hyperpolarized potentials, V is the membrane potential, V1/2 is the voltage at which Po=0.5(1+Pmin), and k is the slope factor. This assumes a maximal Po of 1. Function of the two independent gates in the hClC-1 channel, the fast gate working on each single protopore, and the common (slow) gate operating on both protopores simultaneously [30], could be extracted from the data obtained above, as follows:

|

(3) |

and

|

(4) |

where a1=A1/Imax and c=C/Imax.

Eqn (2) was then used to derive separate V1/2 values for each of the Pofast and Pocommon curves, this time using the data points calculated from eqns (3) and (4).

RESULTS

How does the extent of C-terminal truncation affect channel function?

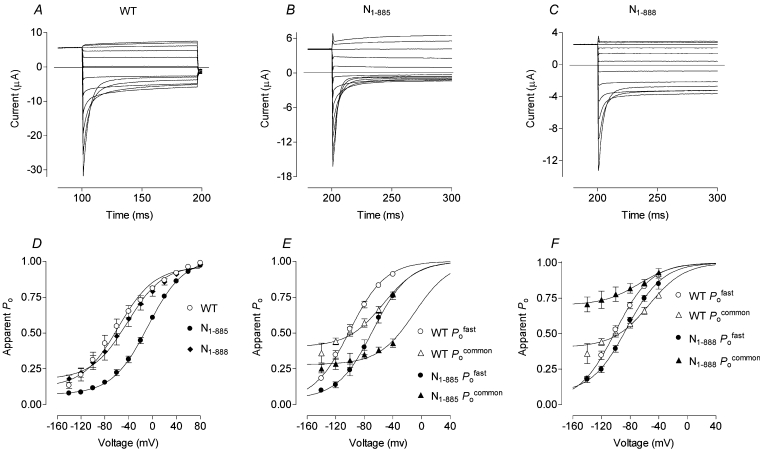

Voltage clamping produced currents indistinguishable from water-injected negative controls in oocytes injected with C-terminal truncation constructs N1–600 (truncated just before CBS1) and N1–720 (truncated about midway between CBS1 and CBS2), as well as N1–862, N1–868, N1–871 and N1–878 (deletion of the final 125, 120, 117 and 110 amino acids of hClC-1 respectively) (results not shown). Deletion of the final 103 amino acids (N1–885, just one residue beyond the myotonic goat mutation which is equivalent to A885P in hClC-1 [31]), however, allowed chloride currents, although of mutant form (altered and kinetically different from WT) (Figures 3A and 3B), with channel open probability being shifted to approx. 40 mV more positive than WT (Figures 3D and 3E; Table 1). For truncation N1–888 (deletion of the final 100 residues), chloride currents were smaller (Figure 3C) but there was no marked shift in Po for this channel (Figure 3D; Table 1). Minimum Po of the common gate at very negative potentials, however, increased from approx. 0.36 in WT to approx. 0.7 in N1–888 (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. Voltage-clamp analysis shows that specific hClC-1 carboxyl tail truncations (as also for deletions and mutations shown in subsequent Figures) are compatible with function.

Chloride current traces were obtained by two-electrode voltage clamp from oocytes expressing WT hClC-1 (A) and the C-terminal truncations N1–885 (B) and N1–888 (C). Currents were recorded 48–72 h after RNA injection in response to voltage steps of 100 ms duration from +80 to −140 mV following a conditioning pulse to +40 mV for 100 or 200 ms. Apparent overall Po curves are plotted (D) and are separated into open probabilities for the fast and common gates (E, F). Apparent Po values were derived from peak chloride currents and fitted with Boltzmann distribution curves.

Table 1. V1/2 of channel open probability (Po), fast gating (Pofast) and common gating (Pocommon) for truncations, alanine substitutions and co-expression of N1–720 with short peptides.

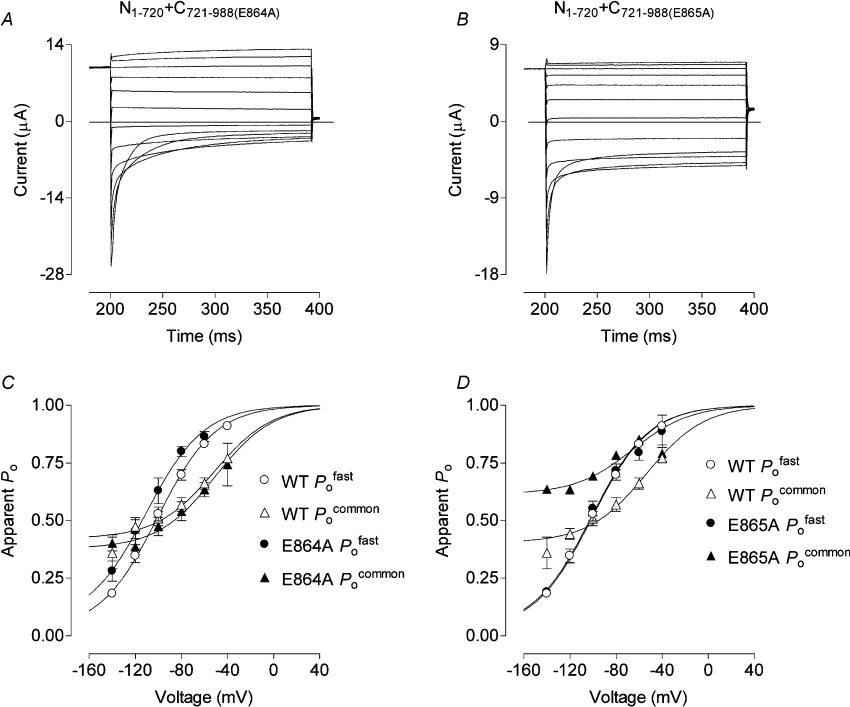

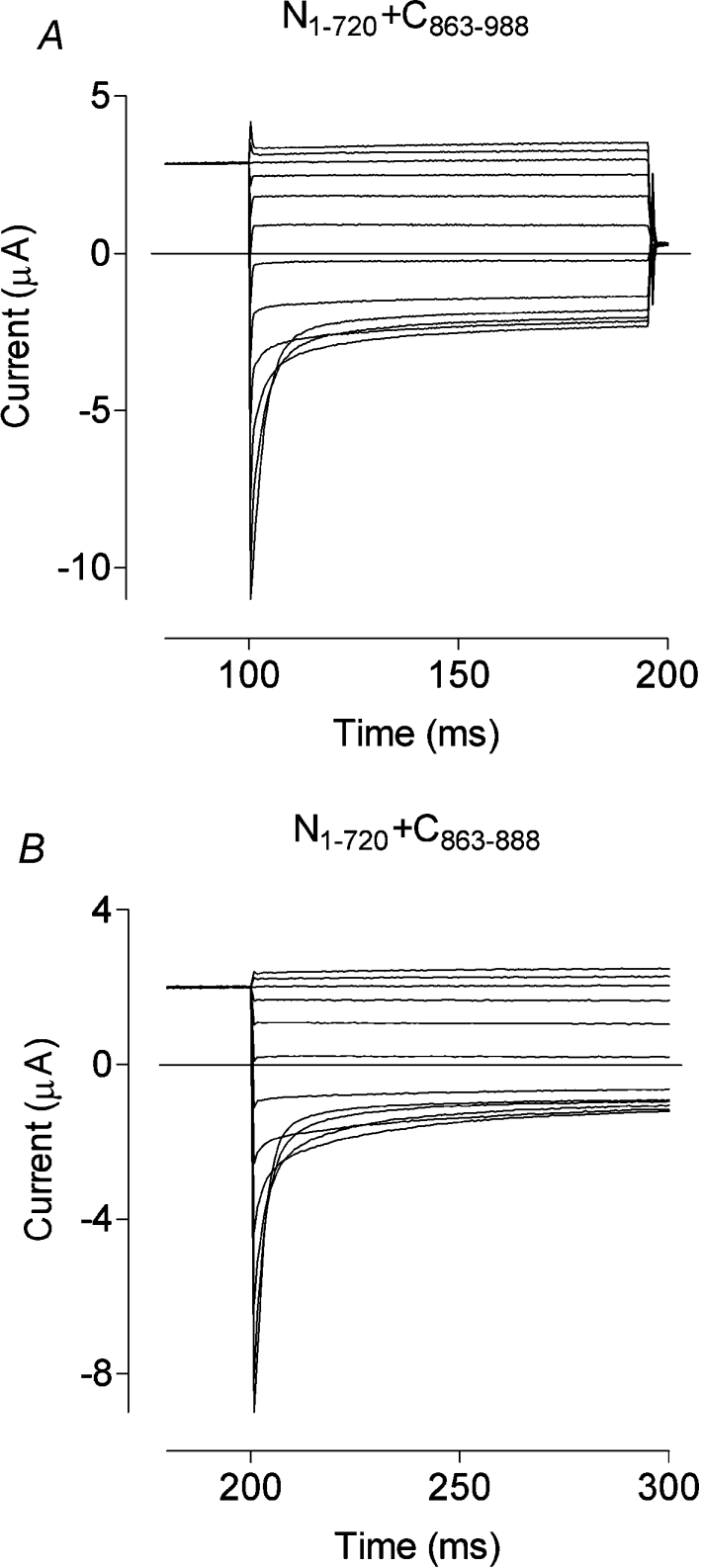

Peak tail currents were used to derive Po values and fast and common gating parameters as described in the Experimental section. Measurements are given in mV as mean±S.E.M. Truncations: the overall Po curve of the truncation N1–885 (removal of the final 103 residues) was approx. 45 mV more positive than WT, and Pofast and Pocommon were some 30–40 mV more positive than WT as revealed by V1/2 values. For truncation N1–888 (the removal of the final 100 amino acids), the V1/2 values for the Po, Pofast and Pocommon curves were similar to WT although the minimum value of Pocommon was larger (Figure 1). Alanine substitutions: the results of alanine substitution for Glu865 in the co-expression N1–720+C721–988(E865A) or of both Glu864 and Glu865 in N1–720+C721–988(E865A, E865A) were different from all the other mutant currents, as the overall Po curves were shifted towards more negative voltages. Fast gating was similar to WT, and the entire shift in Po could be attributed to common gating. The Po, Pofast and Pocommon curves for alanine substitutions of Glu864 alone in N1–720+C721–988(E864A) and of Leu866, Gln867 and Lys868 in N1–720+C721–988(L866A, Q867A, K868A) were similar to WT. Co-expression of G721X with short peptides: co-expression of carboxyl tail truncation N1–720 with C863–888 (26 amino acids) or C863–900 (38 amino acids), which are missing both the 142 amino acids between CBS1 and CBS2 and the final 100 or 88 amino acids respectively, gave smaller chloride currents but the Po curves were similar to WT.

| RNA (no. of oocytes) | V1/2 of Po (mV) | V1/2 of Pofast (mV) | V1/2 of Pocommon (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT hClC-1 (13) | −56.4±2.1 | −102.8±1.6 | −47.7±4.7 |

| N1–885 (10) | −11.9±1.0 | −67.3±3.8 | −10.0±5.4 |

| N1–888 (10) | −47.4±1.5 | −79.3±2.0 | −67.4±7.9 |

| N1–720+C863–988 (10) | −57.1±1.7 | −91.8±1.9 | −50.5±4.4 |

| N1–720+C863–900 (12) | −46.8±1.5 | −92.3±1.8 | −34.1±4.2 |

| N1–720+C863–888 (16) | −62.3±1.6 | −98.9±0.8 | −35.5±4.4 |

| N1–720+C721–988 (10) | −60.1±1.1 | −107.8±1.7 | −59.3±2.9 |

| N1–720+C721–988(E864A, E865A) (7) | −83.5±2.3 | −102.8±3.1 | −81.2±6.1 |

| N1–720+C721–988(L866A, Q867A, K868A) (13) | −52.7±1.7 | −111.1±2.5 | −34.8±7.7 |

| N1–720+C721–988(E864A) (10) | −69.6±2.2 | −111.6±2.1 | −44.9±8.6 |

| N1–720+C721–988(E864A) (11) | −75.7±1.9 | −100.7±1.6 | −75.1±7.6 |

Can channels be functionally reconstituted from complementary components split within or shortly after CBS2?

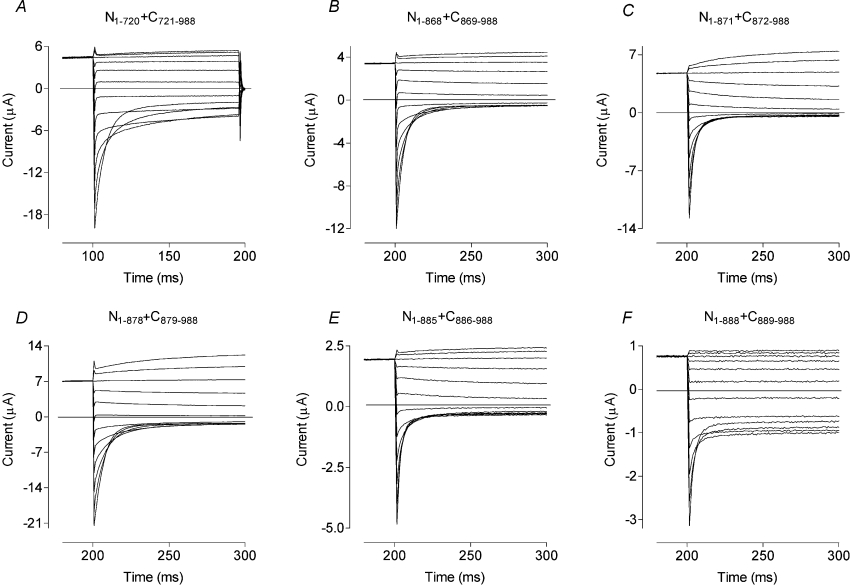

We co-expressed six split channel components (N1–862+C863–988, N1–868+C869–988, N1–871+C872–988, N1–878+C879–988, N1–885+C886–988 and N1–888+C889–988) and the positive control N1–720+C721–988 (Figure 2; [7]) in oocytes (Figure 4). As expected, N1–720+C721–988 yielded currents indistinguishable from those of WT full-length hClC-1 (Figure 4A). All of the other complementary co-expressions also yielded chloride currents, albeit with Po shifted to more positive potentials, except for N1–888+C889–988, which gave small currents (approx. 1/10 of the WT), with significantly larger minimal Po of the common gate (∼0.7). If the cut was made within CBS2 (e.g. N1–862+C863–988 and N1–868+C869–988), the channel's Po was shifted approx. 40 mV more positive than WT (Table 2). If the cut was made immediately after CBS2 (N1–871+C872–988 and N1–878+C879–988), the Po was shifted even further, up to approx. 60 mV more positive than WT (Table 2). Co-expression of N1–885 or N1–888 with their complementary tails, C886–988 or C889–988 respectively, did not improve channel function when compared with the expression of N1–885 or N1–888 alone (Table 2).

Figure 4. Current traces obtained, as for Figure 3, from oocytes expressing truncated ClC-1 constructs co-expressed with their complementary C-terminal peptide.

Typical sets of currents are shown for N1–720 co-expressed with C721–988 (A), N1–868 co-expressed with C869–988 (B), N1–871 co-expressed with C872–988 (C), N1–878 co-expressed with C879–988 (D), N1–885 co-expressed with C886–988 (E) and N1–888 co-expressed with C889–988 (F). By comparison with the currents for N1–720 co-expressed with C721–988, which are close to WT in their characteristics, currents from the other co-expressions are either obviously mutant or quite small.

Table 2. Characteristics of C-terminal truncations and complementary co-expressions.

Column 1 lists the co-expressed RNAs. Column 2: ‘Δ’ indicates deletion; ‘split’ means the two partial proteins are complementary to each other and there are no missing or overlapping residues in between; ‘missing xx aa’ indicates the number of amino acids absent between the two partial complements, and ‘overlap’ gives the number of amino acids overlapped by co-expressing two partial channels. Column 3 describes the chloride currents that were detected from oocytes: ‘WT’ means that the current traces were indistinguishable from the WT hClC-1, and ‘mutant’ means the current kinetics were altered and measurably different from that of the WT. Column 4: V1/2 values for overall Po. Measurements are given in mV as mean±S.E.M. Column 5: number of oocytes tested and utilized in computing Po curves. aa, amino acids.

| RNA injected | Protein state | Cl− currents | V1/2 (mV) | No. of oocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT hClC-1 | Full-length | WT | −56.4±2.1 | 15 |

| N1–600 | Δfinal 388 aa | No currents | 30 | |

| N1–600+C721–988 | ΔCBS1 | No currents | 15 | |

| N1–720 | Δfinal 268 aa | No currents | 15 | |

| N1–720+C721–988* | Split between CBS1 and CBS2 | WT | −60.1±1.1 | 10 |

| N1–720+C863–988 | Missing 142 aa | WT | −57.1±1.7 | 8 |

| N1–720+C869–988 | Missing 148 aa | No currents | 10 | |

| Co-expressions of N1–720 with our C-tail constructs missing 151–168 aa also had no currents | ||||

| N1–862 | Δfinal 126 aa | No currents | 20 | |

| N1–862+C721–988 | Overlap 142 aa | Small mutant† | −37.7±6.2 | 7 |

| N1–862+C863–988 | Split within CBS2 | Small mutant† | −6.5±2.7 | 10 |

| N1–862+C869–988 | Missing 6 aa | No currents | 20 | |

| Co-expressions of N1–862 with our C-tail constructs missing 9–26 aa also had no currents | ||||

| N1–868 | Δfinal 120 aa | No currents | 20 | |

| N1–868+C721–988 | Overlap 148 aa | Mutant† | −18.2±3.0 | 4 |

| N1–868+C863–988 | Overlap 6 aa | Mutant† | −6.8±1.7 | 7 |

| N1–868+C869–988 | Split within CBS2 | Mutant† | −10.9±2.4 | 6 |

| N1–868+C872–988 | Missing 3 aa | Mutant† | −11.4±1.4 | 2 |

| Co-expressions of N1–868 with our C-tail constructs missing 10–20 aa also had mutant currents | ||||

| N1–871 | Δfinal 117 aa | No currents | 10 | |

| N1–871+C721–988 | Overlap 151 aa | Mutant† | +1.2±1.6 | 8 |

| Co-expressions of N1–871 with our other C-tail constructs produced similar mutant currents irrespective of overlap, complementary splitting after CBS2 or missing 7–17 aa | ||||

| N1–878 | Δfinal 110 aa | No currents | 10 | |

| N1–878+C721–988 | Overlap 158 aa | No currents | 10 | |

| N1–878+C863–988 | Overlap 16 aa | No currents | 10 | |

| N1–878+C869–988 | Overlap 10 aa | Mutant† | +4.5±1.0 | 14 |

| N1–878+C872–988 | Overlap 7 aa | Mutant† | −4.7±3.0 | 4 |

| N1–878+C879–988 | Split after CBS2 | Mutant† | −3.0±2.6 | 12 |

| N1–878+C886–988 | Missing 7 aa | Mutant† | −9.0±1.8 | 12 |

| N1–878+C889–988 | Missing 10 aa | Mutant† | −17.0±2.9 | 14 |

| N1–885 | Δfinal 103 aa | Mutant† | −11.9±1.0 | 10 |

| N1–885+C721–988 | Overlap 165 aa | Mutant† | −18.0±1.8 | 5 |

| N1–885+C863–988 | Overlap 23 aa | Mutant† | −19.2±2.7 | 16 |

| N1–885+C869–988 | Overlap 17 aa | Mutant† | −16.9±2.9 | 12 |

| N1–885+C872–988 | Overlap 14 aa | Mutant† | −22.4±3.0 | 4 |

| N1–885+C879–988 | Overlap 7 aa | Mutant† | −30.1±7.3 | 3 |

| N1–885+C886–988 | Split after CBS2 | Mutant† | −33.4±2.5 | 11 |

| N1–885+C889–988 | Missing 3 aa | Mutant† | −28.8±3.1 | 12 |

| N1–888 | Δfinal 100 aa | Small mutant‡ | −47.4±1.5 | 10 |

| N1–888+C721–988 | Overlap 168 aa | Small mutant‡ | −56.5±3.4 | 4 |

| N1–888+C863–988 | Overlap 26 aa | Small mutant‡ | −65.7±3.1 | 7 |

| N1–888+C869–988 | Overlap 20 aa | Small mutant‡ | −79.0±5.4 | 6 |

| N1–888+C872–988 | Overlap 17 aa | No currents | 14 | |

| N1–888+C879–988 | Overlap 10 aa | No currents | 4 | |

| N1–888+C886–988 | Overlap 3 aa | Small mutant‡ | −66.0±4.0 | 1 |

| N1–888+C889–988 | Split after CBS2 | Small mutant‡ | −58.2±3.6 | 6 |

* Positive control for co-expression of split channel components in oocytes.

† V1/2 shifted to more positive potentials.

‡ Larger minimum values of Pocommon.

How well can the recombination of hClC-1 accommodate the absence or overlap of intermediate sections of the carboxyl tail?

To answer this question, we co-expressed each C-terminal truncation with each of our seven C-terminal peptides, in turn (Table 2). None of the C-terminal peptides were functional when expressed alone (results not shown). Channel function was completely lost when N1–600 was co-expressed with C721–988 or when N1–720 or N1–862 was co-expressed with any C-terminal peptide beginning after Leu863 (C863–988), e.g. C869–988 and C872–988. In contrast, however, N1–868, N1–871 and N1–878 gave chloride currents (although of mutant form), when co-expressed with most of the other tails, except that no currents could be detected with N1–878+C721–988 and N1–878+C863–988 (Table 2). In all of the co-expressions that yielded chloride currents, except those with N1–888, channel open probability was shifted towards more positive voltages, by amounts ranging from approx. 30 to 60 mV when compared with the WT (Table 2). While functional recombination of hClC-1 could be achieved with a variety of overlaps (Table 2), the most conspicuous result was that a functional form, with WT characteristics, was achievable in the absence of the 142 amino acids between Ser720 and Leu863 (the N1–720+C863–988 co-expression). Though the currents were smaller, they were qualitatively the same as WT (Figure 5A). Overall open probability was not shifted along the voltage axis, V1/2=−57.1±1.7 mV, (n=8), and the V1/2 of fast and of common gating was not changed (Table 1).

Figure 5. Current traces obtained, as for Figure 3, from oocytes expressing N1–720 co-expressed with partially complementary, short carboxyl tail fragments.

Typical sets of currents are shown for N1–720 co-expressed with C863–988 (A) and for N1–720 co-expressed with C863–888 (B). Although tending to be smaller than WT, both sets of currents are close to WT in their other characteristics.

What minimum peptide length might then restore channel function to G721X?

To narrow down the functionally important region in the C-terminal of hClC-1, we co-expressed N1–720 with, firstly, a 38–amino-acid peptide Leu863–Pro900 (C863–900) and then a 26-amino-acid peptide Leu863–Arg888 (C863–888; Figure 5B). Surprisingly, small but qualitatively unchanged chloride currents were obtained from both of these co-expressions (Table 1).

Which residues in the minimal peptide might be most significant?

Since N1–720+C863–988 gave WT and N1–862+C863–988 gave small currents, while N1–720+C869–988 and N1–862+C869–988 co-expressions gave no currents (Table 2), we postulated that residues Glu864-Lys868 (EELQK, a conserved region in mammalian ClC-1) might be essential for channel function. Co-expression of N1–720–expression of N1–720 was therefore tried with alanine substitutions within the EELQK motif of C721–988. Mutant chloride currents were produced with C721–988(E864A, E865A) (AALQK), whereas with C721–988(L866A, Q867A, K868A) (EEAAA), currents were not different from WT (Table 1). Single alanine substitutions in the C-terminal complement as C721–988(E864A)–terminal complement as C721–988(E864A) (AELQK) then gave currents and fast and common gating that were not significantly different from WT (Figures 6A and 6C), but as C721–988(E865A) (EALQK), currents and common gating were altered as for the AALQK mutant (Figure 6B; Table 1). The Po of N1–720+C721–988(E865A) was shifted by approx. 30 mV towards more negative voltages and the common component of current relaxations was considerably reduced. Separation of the two gating processes revealed that fast gating was the same as for WT. Apparently entirely responsible for the change in Po was a larger minimum Pocommon (∼0.6 compared with ∼0.36 in WT) and a negative shift in the voltage dependence of common gating (Figure 6D; Table 1). While the length of the EELQK motif might be important, it seems that, overall, the character of its residues is not. In our alanine scan, only E865A affected gating, reducing closure of the common gate of this mutant at negative potentials.

Figure 6. Chloride current traces, Pofast and Pocommon curves obtained, as before, from oocytes that co–expressed N1–720 and C721–988 containing the alanine substitutions E864A or E865A.

Typical sets of currents are shown for N1–720+C721–988(E864A) (A) and N1–720+C721–988(E865A) (B). Apparent Po values for each of these E864A and E865A substitutions (C and D respectively) were derived from peak chloride currents and fitted with Boltzmann distribution curves. There is noticeably less common gating in currents from the E865A substitution and this is explained by a greater open probability of the common gates at negative potentials.

DISCUSSION

In an earlier study [9], based on truncations and deletions in the carboxyl tail of rClC-1, we suggested the presence of a functionally essential sequence of amino acids from the end of CBS2 to Arg894 (equivalent to Arg888 in hClC-1). Further analysis of this region in hClC-1 (Figure 1), using additional truncations and functional reconstitution from split channels, now reinforces our earlier suggestion and more closely defines the essential sequence as lying between Ala862 and Asn889.

Naturally occurring truncations in the carboxyl tail of hClC-1 have been known for many years as a cause of myotonia. In general, if the truncation occurs before CBS2, it causes the recessive type of myotonia; after CBS2, it causes the milder dominant myotonia [4]. A natural, myotonia-causing truncation, R894X, gave a large reduction of, but did not completely abolish, currents when expressed in oocytes as N1–893 [20]. Our, not very different, N1–888 truncation similarly produced small currents. Truncation N1–885 (loss of the final 103 amino acids) gave normal sized but more slowly activating currents, which suggests that normal numbers of channels, albeit kinetically compromised, are being expressed. No currents could be elicited from truncations eliminating 110 or more amino acids (shorter than N1–878). Others have also found that truncations in this region of ClC-0 and ClC-1 have various effects that do not seem to be directly related to tail length [8–13], but some of which might be explained by differences in channel type or expression system. Some of these effects have been attributed to an influence of the cytoplasmic tail on the outer pore vestibule [13].

Recent research suggests that the pairs of CBS domains found in the mainly hydrophilic carboxyl tails of eukaryotic CLCs are involved in sensing cellular energy status [14–16,32]. This is believed to be accomplished via a putative adenosine ligand-binding site, or pocket, formed by the juxtaposition of two CBS domains. Naturally occurring mutations within and between the CBS domain pairs of several different protein families are associated with diseases ranging from the myotonias (hClC-1), epilepsy (ClC-2), Bartter's syndrome (ClC-Kb), Dent's disease and its phenotypic variants (ClC-5), osteopetrosis (ClC-7), through homocystinuria (CBS, itself), retinitis pigmentosa [IMPDH (inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase)] and cardiac conductance defects similar to those in Wolf–Parkinson–White syndrome [AMPKγ2 (AMP-activated protein kinase γ2], to a skeletal-muscle glycogen storage disease (AMPKγ3), in Hampshire pigs [32,33].

Interestingly, in view of this new-found significance of CBS domain pairs, only one member of the pair seems necessary for basic ClC-1 function. Hryciw et al. [9] and Estévez et al. [10] have shown that the major part or all of CBS2 can be deleted in-frame without eliminating function, provided that CBS1 is retained. Further evidence in support of a requirement for an intact CBS1 comes from split channel experiments. Reconstitution of functional channels could be achieved if the split was between CBS1 and CBS2 [7,10,11]. No chloride currents could be elicited if the split in the tail occurred before or within CBS1, or if it eliminated CBS1 (the present results; [7,10], cf. also [8,24,34]). In contrast with the results of these studies, Hebeisen et al. [11] have found kinetically normal chloride currents after deleting CBS1 plus various lengths of interdomain linker. With increasing deletion length, currents simply diminished in amplitude. In the same series of experiments, absence of CBS2 could be tolerated only if CBS1 was substituted in CBS2's normal position in the carboxyl tail. This suggests that the single essential CBS domain must be at the position normally occupied by CBS2. These apparent anomalies must eventually be resolved in line with the determination, above, that WT hClC-1 currents are modified by adenosine ligands [16] and with the question of whether this remains true for any of the functional versions of hClC-1 that have only a single CBS domain.

To delineate further the relevance of CBS2 and the immediate post-CBS2 sequence, we have tested many combinations of overlapping, exactly and partially complementary split channels (Table 2). In this way, we determined that the essential sequence must begin at or about Leu863 and, using our knowledge of functional truncations (above), must end at or about Arg888. Essentially, we have found relatively normal currents in co-expressions of N1–720+C863–988 (absence of most of the region between CBS1 and CBS2, including the greater part of CBS2), N1–720+C863–900 and N1–720+C863–888 (absence of as many as 100 C-terminal amino acids as well as most of the interdomain linker and the greater part of CBS2). A requirement for the integrity of the Leu863–Arg888 sequence (C863–888–terminal amino acids as well as most of the interdomain linker and the greater part of CBS2). A requirement for the integrity of the Leu863–Arg888 sequence (C863–888) is seen in the absence of currents from truncations of greater than 103 amino acids and from co-expressions of N1–720 with peptides beginning at Ala869 or beyond. Where the split was within this region, even exact complements (e.g. splits at Ala869, Gly872 and Gln879) have a relatively large effect on function, there being a depolarizing shift in Po of up to approx. 60 mV.

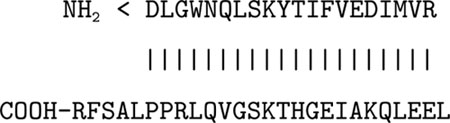

Most likely, the C863–888 peptide provides an appropriate interaction with a complementary binding site made up of the sequence between helix R and CBS1 and/or of the cytoplasmic loops of the hClC-1 protein, thereby allowing the channel to become functional. In IMPDH, CBS pairing causes portions of the peptide sequence downstream from β3–1 protein, thereby allowing the channel to become functional. In IMPDH, CBS pairing causes portions of the peptide sequence downstream from β3 of CBS2 (from and including α2 of CBS2) and upstream from CBS1 to lie partially adjacent and antiparallel to each other (see, e.g., [15]). For hClC-1, this can be approximated, first for the helix R-CBS linker (forward sequence from Asp592 to Arg611) and below it for our Leu863–Arg888 peptide (aligned antiparallel) as follows:

|

There is some possibility for electrostatic and other interactions between these sequences.

We are reassured that we are seeing genuine reconstitution when N1–720 is co–expressed with the C721–988(E865A) mutant carboxyl tail complement (equivalent to E865A). In this case, common gating is greatly diminished, the open probability of common gating being increased and shifted in the hyperpolarizing direction so that this gate is seldom closed. Independently, while seeking CBS2 residues that might be involved in gating, trafficking or regulation of CLC channels, Estévez et al. [10] have found that common gating is similarly suppressed in E865K in hClC-1 and by its equivalent, E763K, in ClC-0. Both results support an importance of this part of CBS2 and the involvement of Glu865 (Glu763 in ClC-0) in enabling common gate closure. It could be that Glu656 in the exactly equivalent (third) position in α2 of CBS1 has allowed it to substitute for CBS2 in the hClC-1 deletion studies undertaken by Hebeisen et al. [11].

Perplexing disagreements between our present results and those of others include the apparent significance they have found for CBS2 in combined co-expression deletion experiments [10]. When they express full-length constructs with in-frame deletions, however, our conclusions as to the dispensability of CBS2 concur [10]. Also, in contrast with our observations, a seemingly essential short sequence, immediately preceding CBS2, has been proposed as a result of full-length expressions with in-frame deletions and combined co-expression deletion experiments [10]. There are similar puzzling discrepancies between our findings and those of others [8,10–12] with respect to the effects of truncation length. We have no immediate explanation for these anomalies, apart from invoking differences between expression systems and between the exact constructs being expressed. Nor can we account for the distinct reduction in common gating in our N1–888 truncation, whereas in the co–expression, N1–720+C863–888, gating is clearly equivalent to WT.

Finally, exactly how our carboxyl tail fragments as small as C863–888 rescue function in truncations as severe as N1–720, requires comment. Protein–protein interaction between N1–720 and C863–888 may allow trafficking to the plasma membrane owing to a signal within C863–888 or a signal unmasked in or between N1–720 and C863–888 by the interaction. Alternatively, inactive N1–720 may be trafficked to and resident alone in the plasma membrane, only becoming active when soluble cytoplasmic C863–888 interacts appropriately with it. There is some strong evidence for the former explanation from the trafficking failure of similarly truncated ClC-0 and ClC-1 constructs [8,10]. In contrast, confocal microscopic evidence for or against trafficking of even more severely truncated ClC-1, ClC-2 or ClC-5 [11,24,35] may be unreliable, owing to the resolving power of these microscopes being inadequate to determine whether a fluorescently labelled construct is in the plasma membrane or merely near it in the cytoplasm. We therefore propose that the interaction is necessary for trafficking and plasma membrane insertion rather than merely for activating a previously inserted channel component. Appropriate interactions involving specific carboxyl tail motifs then permit activation and regulate gating.

To summarize, in contrast with the conclusions of Fong et al. [12] but in partial agreement with Hebeisen et al. [11] and general agreement with Estévez et al. [10], we find that much of the interdomain linker, between CBS1 and CBS2, is dispensable. In a novel extension of these studies, we have found that most of CBS2 is simultaneously dispensable along with the C-terminal 100 amino acids of the carboxyl tail, leaving only a 26-amino-acid peptide C863–888 (Leu863–Arg888) that seems to be necessary and sufficient to provide functional complementation to the N1–720 truncation of hClC-1. In the N-terminal of this peptide, Glu865 is involved in allowing the closure of the common gate.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Christopher J. Bagley (Protein Laboratory, Hanson Institute, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, Adelaide, SA, Australia and Department of Medicine, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia) for helpful discussions in relation to protein structure and for his critical review of relevant parts of this paper. This work was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Australian Research Grants Committee and by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Association of South Australia and the Research Committee of the University of South Australia.

References

- 1.Bretag A. H. Muscle chloride channels. Physiol. Rev. 1987;67:618–724. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmeyer K., Klocke R., Ortland C., Gronemeier M., Jockusch H., Grunder S., Jentsch T. J. Inactivation of muscle chloride channel by transposon insertion in myotonic mice. Nature (London) 1991;354:304–308. doi: 10.1038/354304a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jentsch T. J., Stein V., Weinreich F., Zdebik A. A. Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:503–568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colding-Jørgensen E. Phenotypic variability in myotonia congenita. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:19–34. doi: 10.1002/mus.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankodi A., Takahashi M. P., Jiang H., Beck C. L., Bowers W. J., Moxley R. T., Cannon S. C., Thornton C. A. Expanded CUG repeats trigger aberrant splicing of ClC-1 chloride channel pre-mRNA and hyperexcitability of skeletal muscle in myotonic dystrophy. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutzler R., Campbell E. B., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 Å reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature (London) 2002;415:287–294. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt-Rose T., Jentsch T. J. Reconstitution of functional voltage-gated chloride channels from complementary fragments of CLC-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20515–20521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maduke M., Williams C., Miller C. Formation of CLC-0 chloride channels from separated transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1315–1321. doi: 10.1021/bi972418o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hryciw D. H., Rychkov G. Y., Hughes B. P., Bretag A. H. Relevance of the D13 region to the function of the skeletal muscle chloride channel, ClC-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:4304–4307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estévez R., Pusch M., Ferrer-Costa C., Orozco M., Jentsch T. J. Functional and structural conservation of CBS domains from CLC chloride channels. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2004;557:363–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebeisen S., Biela A., Giese B., Muller-Newen G., Hidalgo P., Fahlke C. The role of the carboxyl terminus in ClC chloride channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13140–13147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong P., Rehfeldt A., Jentsch T. J. Determinants of slow gating in ClC-0, the voltage-gated chloride channel of Torpedo marmorata. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C966–C973. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebeisen S., Fahlke C. Carboxy-terminal truncations modify the outer pore vestibule of muscle chloride channels. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1710–1720. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott J. W., Hawley S. A., Green K. A., Anis M., Stewart G., Scullion G. A., Norman D. G., Hardie D. G. CBS domains form energy-sensing modules whose binding of adenosine ligands is disrupted by disease mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:274–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI19874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams J., Chen Z. P., Van Denderen B. J., Morton C. J., Parker M. W., Witters L. A., Stapleton D., Kemp B. E. Intrasteric control of AMPK via the γ1 subunit AMP allosteric regulatory site. Protein Sci. 2004;13:155–165. doi: 10.1110/ps.03340004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennetts B., Rychkov G. Y., Ng H. L., Morton C. J., Stapleton D., Parker M. W., Cromer B. A. Cytoplasmic ATP-sensing domains regulate gating of skeletal muscle ClC-1 chloride channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32452–32458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwappach B., Stobrawa S., Hechenberger M., Steinmeyer K., Jentsch T. J. Golgi localization and functionally important domains in the NH2 and COOH terminus of the yeast CLC putative chloride channel Gef1p. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15110–15118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunder S., Thiemann A., Pusch M., Jentsch T. J. Regions involved in the opening of ClC-2 chloride channel by voltage and cell volume. Nature (London) 1992;360:759–762. doi: 10.1038/360759a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George A. L., Jr, Sloan-Brown K., Fenichel G. M., Mitchell G. A., Spiegel R., Pascuzzi R. M. Nonsense and missense mutations of the muscle chloride channel gene in patients with myotonia congenita. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994;3:2071–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer-Kleine C., Steinmeyer K., Ricker K., Jentsch T. J., Koch M. C. Spectrum of mutations in the major human skeletal muscle chloride channel gene (CLCN1) leading to myotonia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;57:1325–1334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., George A. L., Jr, Griggs R. C., Fouad G. T., Roberts J., Kwiecinski H., Connolly A. M., Ptacek L. J. Mutations in the human skeletal muscle chloride channel gene (CLCN1) associated with dominant and recessive myotonia congenita. Neurology. 1996;47:993–998. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plassart-Schiess E., Gervais A., Eymard B., Lagueny A., Pouget J., Warter J. M., Fardeau M., Jentsch T. J., Fontaine B. Novel muscle chloride channel (CLCN1) mutations in myotonia congenita with various modes of inheritance including incomplete dominance and penetrance. Neurology. 1998;50:1176–1179. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papponen H., Toppinen T., Baumann P., Myllyla V., Leisti J., Kuivaniemi H., Tromp G., Myllyla R. Founder mutations and the high prevalence of myotonia congenita in northern Finland. Neurology. 1999;53:297–302. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo L., Xiong W., Qian T., Sun H., Wills N. K. Coexpression of complementary fragments of ClC-5 and restoration of chloride channel function in a Dent's disease mutation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C79–C89. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00009.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz C., Pusch M., Jentsch T. J. Heteromultimeric CLC chloride channels with novel properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:13362–13366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusch M., Steinmeyer K., Koch M. C., Jentsch T. J. Mutations in dominant human myotonia congenita drastically alter the voltage dependence of the CIC-1 chloride channel. Neuron. 1995;15:1455–1463. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rychkov G. Y., Pusch M., Astill D. S., Roberts M. L., Jentsch T. J., Bretag A. H. Concentration and pH dependence of skeletal muscle chloride channel ClC-1. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 1996;497:423–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pusch M., Ludewig U., Rehfeldt A., Jentsch T. J. Gating of the voltage-dependent chloride channel ClC-0 by the permeant anion. Nature (London) 1995;373:527–531. doi: 10.1038/373527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennetts B., Roberts M. L., Bretag A. H., Rychkov G. Y. Temperature dependence of human muscle ClC-1 chloride channel. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2001;535:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saviane C., Conti F., Pusch M. The muscle chloride channel ClC-1 has a double-barreled appearance that is differentially affected in dominant and recessive myotonia. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:457–468. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck C. L., Fahlke C., George A. L., Jr Molecular basis for decreased muscle chloride conductance in the myotonic goat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:11248–11252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kemp B. E. Bateman domains and adenosine derivatives form a binding contract. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:182–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pusch M. Structural insights into chloride and proton-mediated gating of CLC chloride channels. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1135–1144. doi: 10.1021/bi0359776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L., Schaerer M., Lu Z. H., Lang D., Joncourt F., Weis J., Fritschi J., Kappeler L., Gallati S., Sigel E., et al. Exon 17 skipping in CLCN1 leads to recessive myotonia congenita. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:670–676. doi: 10.1002/mus.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemeyer M. I., Yusef Y. R., Cornejo I., Flores C. A., Sepulveda F. V., Cid L. P. Functional evaluation of human ClC-2 chloride channel mutations associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Physiol. Genomics. 2004;19:74–83. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00070.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]