Abstract

The Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase plays a role in many cellular processes including the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. The PIS1 (phosphatidylinositol synthase gene) encoding the enzyme Pis1p which catalyses the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol from CDP-diacyglycerol and inositol, was isolated in a screen for multicopy suppressors of the rsp5 temperature sensitivity phenotype. Suppression was allele non-specific. Interestingly, expression of PIS1 was 2-fold higher in the rsp5 mutant than in wild-type yeast, whereas the introduction of PIS1 in a multicopy plasmid increased the level of Pis1p 6-fold in both backgrounds. We demonstrate concomitantly that the expression of INO1 (inositol phosphate synthase gene) was also elevated approx. 2-fold in the rsp5 mutant as compared with the wild-type, and that inositol added to the medium improved growth of rsp5 mutants at a restrictive temperature. These results suggest that enhanced phosphatidylinositol synthesis may account for PIS1 suppression of rsp5 defects. Analysis of lipid extracts revealed the accumulation of saturated fatty acids in the rsp5 mutant, as a consequence of the prevention of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. Overexpression of PIS1 did not correct the cellular fatty acid content; however, saturated fatty acids (C16:0) accumulated preferentially in phosphatidylinositol, and (wild-type)-like fatty acid composition in phosphatidylethanolamine was restored.

Keywords: fatty acid, phosphatidylinositol synthase (Pis1p), phospholipid, Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, multicopy suppressor

Abbreviations: CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; CDP-DAG, CDP-diacylglycerol; FAR, fatty acid-regulated elements; Hect, homologous to E6-accessory protein C-terminus; LORE, low-oxygen response element; MGA2, multicopy suppressor of gam1 (snf2); PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIS1, PI synthase gene; PS, phosphatidylserine; SC, synthetic complete; SD, synthetic defined; SPT23, multicopy suppressor of tyrosine-induced mutations; ts, temperature sensitive; YEPD, yeast extract peptone dextrose

INTRODUCTION

The regulation of metabolic lipid enzymes is an essential process that affects membrane lipid composition and has an impact upon many cell processes, such as cell growth, organelle function and response to stress etc. [1,2]. Therefore eukaryotes have developed complex mechanisms to regulate lipid biosynthetic pathways. Deregulation of lipid metabolism has been reported in many human diseases, including obesity and atherosclerosis, one of the diseases with the highest morbidity in developed countries [3].

The ratio of saturated to monounsaturated fatty acids that are incorporated into cell membranes contributes to fluidity of the membrane. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, this ratio also affects mitochondrial inheritance [4] and stress responses [5]. The enzyme involved in fatty acid desaturation is the Δ-9 fatty acid desaturase, encoded by the essential OLE1 gene, that converts saturated fatty acyl-CoA (palmityl- and stearyl-) to monounsaturated fatty acid species (palmitoleoyl- and oleoyl-) in an oxygen-dependent manner [6]. The regulation of OLE1 expression is physiologically very important since unsaturated fatty acids contribute to 70–80% of the fatty acyl groups in membrane lipids. The expression of OLE1 is regulated by nutrient fatty acids and molecular oxygen [7], and other physiological conditions, both at the transcriptional and mRNA stability levels [8,9]. Unsaturated fatty acid-dependent repression is mediated by FAR (fatty acid-regulated) elements [9] and hypoxic activation is mediated by LORE (low-oxygen response elements) [7].

Two highly similar and functionally related genes, SPT23 (multicopy suppressor of tyrosine-induced mutations) and MGA2 [multicopy suppressor of gam1 (snf2)], are required for the activation of OLE1 transcription [10]. They are both functionally redundant since neither of the two genes is essential for viability, whereas the double spt23Δmga2Δ mutant is lethal [10]. This lethality is suppressed by the presence of oleic acid in the growth medium. Spt23p and Mga2p are produced as p120 precursors which are anchored as homodimers in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum via their C-terminal transmembrane domain [11,12]. When unsaturated fatty acids become limiting, the Spt23p and Mga2p precursors are ubiquitinated, and one of the dimer subunits is processed into a mature p90 form. Subsequently, p90 with the assistance of the chaperone complex Cdc49p/Ufd1p/Npl4p and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, is released from the p120 membrane-bound subunit and transported into the nucleus where it functions as a transcriptional activator of OLE1 [12]. Mga2p is also essential for the hypoxic induction of OLE1 expression and is a component of the LORE-bound complex [13]. Moreover, it regulates the half-life of the OLE1 transcript by activating the exosomal 3′-5′exonuclease [14].

Ubiquitination of Spt23p and Mga2p is performed by the essential Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase [11], an E3 (ubiquitin ligase) enzyme of the ubiquitination pathway which transfers ubiquitin to lysine residues in protein substrates [15]. Rsp5p contains the C2, WW and catalytic Hect (homologous to E6-accessory protein C-terminus) domains. The C2 domain interacts with phospholipids [16], and three WW domains are involved in protein–protein interactions [15]. The WW3 domain is required for Rsp5p-induced processing of Spt23p [11]. Binding of the Rsp5p WW domains to Spt23p is directed via an LPKY motif, located near the C-terminal transmembrane domain [17]. This interaction is necessary for Spt23p ubiquitination, processing, and OLE1 activation [17]. A similar motif, found in Mga2p, is required for Mga2p binding and ubiquitination by Rsp5p; however, it is not required for Mga2p proteasome-dependent processing, leaving the function of this ubiquitination unknown [17]. Therefore by ubiquitinating Spt23p and Mga2p, Rsp5p is indirectly involved in the regulation of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis and, as a consequence, the rsp5Δ mutant is lethal unless the growth medium is supplemented with oleic acid [11]. Rsp5p also affects many other cellular processes. The best known is the involvement of Rsp5p in endocytosis of plasma membrane transporters and pheromone receptors [18], and in other steps of vesicular trafficking [19]. It also affects transcription and nuclear transport of RNAs [20–23].

In the present study, we report the isolation of the PIS1 gene [PI (phosphatidylinositol) synthase], encoding protein (EC 2.7.8.11) [24], as a multicopy suppressor of rsp5 mutants. In this background, saturated fatty acids resulting from unsaturation preclusion tended to accumulate preferentially within the PI as a consequence of Pis1p overproduction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains, media, growth and transformation conditions

Escherichia coli strain DH5α F' supE44ΔlacU169 (Φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 was used for cloning and plasmid propagation. The S. cerevisiae strains used are described in Table 1. Strain MK15 (from M. Kwapisz, Department of Genetics, IBB PAS, Warsaw) was constructed by the integration of YIpHA-rsp5-19 into the MHY501 strain. Yeast strains containing the PIS1–CAT (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) fusion gene integrated at the GAL4 locus were created by transformation of T8-1D and TZ29 strains using a p911 plasmid digested by SacII and PvuI.

Table 1. Yeast strains used in the present study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| T8-1D | MATα SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 | [36] |

| TZ11 | MATa rsp5-17 ura3-1 SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 lys2-1 leu1 trp5 met4 rsp5-17 | [36] |

| TZ19 | MATa rsp5-9 ura3-1 SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 lsy2-1 leu1 trp5 met4 | [31] |

| TZ29 | MATα rsp5-19 ura3-1 SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 | Laboratory collection |

| MK1 | MATα his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 lys2-801 trp1-1 rsp5::HA–RSP5 | [37] |

| MK3 | MATα his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 lys2-801 trp1-1 rsp5::HA–rsp5-w2 | [37] |

| MK4 | MATα his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 lys2-801 trp1-1 rsp5::HA–rsp5-w3 | [37] |

| MK15 | MATα his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-5 lys2-801 trp1-1 rsp5::HA–rsp5-19 | M. Kwapisz |

| Y25529 | Mat a/α his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0/LYS2 MET15/met15Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 PIS1/pis1::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| PK10 | MATα SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 ura3-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 gal4:: PIS1–CAT | Present study |

| PK11 | MATα rsp5-19 ura3-1 SUP11 ade2-1 mod5-1 lys2-1 leu2-3,112 his4-519 gal4:: PIS1–CAT | Present study |

YEPD (yeast extract peptone dextrose), YEPG (yeast extract peptone galactose), SD (synthetic defined), SC (synthetic complete) and sporulation media were prepared and genetic manipulations were performed as described by Sherman [25]. YEPD medium was supplemented with 20 mg/l inositol or 1% Tween-80 as indicated. SC-ura-inositol contained the same ingredients as SC media except for the presence of uracil and inositol. SD+cas medium contained the same ingredients as SD plus 1% casamino acids, 20 mg/l tryptophan and 20 mg/l adenine.

Suppression of the ts (temperature-sensitive) phenotype of various mutants by the YEpHA-PIS1 plasmid was monitored by a drop test. Appropriate transformants were suspended in water, and serial 10-fold dilutions were plated on to YEPD. Growth was observed after a 2-day incubation at 34 or 37 °C as indicated.

Plasmid constructions

The pMA109 multicopy plasmid expressing the PIS1 promoter (PIS1–lacZ) [26], the integrative plasmid p911 expressing the PIS1 promoter (PIS1–CAT) [27], and the multicopy plasmid pJH359 expressing the INO1 (inositol phosphate synthase) promoter (INO1–lacZ) [28] were used.

Plasmid AJ2 bearing a fragment of the DBF2 gene and genes MRD1 and PIS1 was isolated from the pFL44L [29] based (URA3 marker) multicopy library, as complementing the growth defect of the TZ19 rsp5-9 strain on YEPD at 37 °C [30]. AJ2 was digested with SacI and religated to obtain AJ2ΔSac bearing only the PIS1 gene. To obtain YCpHA-PIS1, the EcoRI–EcoRI fragment, containing the PIS1 promoter and an ATG codon, was transferred from the AJ2 plasmid and cloned into pUC19. A NotI site was introduced after the ATG codon by reverse PCR using specific primers (Table 2) for site-directed mutagenesis. The sequence of the plasmid after mutagenesis was confirmed. The NotI–NotI fragment encoding a triple HA tag from pBF30 [31], was cloned into the NotI site to construct the pPK1 plasmid. The EcoRI–SphI fragment of AJ2, containing a fragment of the PIS1 gene was cloned into YCp33 [32]. The EcoRI–EcoRI fragment from pPK1 was then cloned into the EcoRI site. To obtain YEpHA-PIS1, the PvuII–SphI fragment of YCpHA-PIS1 containing the HA–PIS1 gene was cloned into plasmid pFL44L. YEpHA-pis1(H114Y) was constructed by PCR mutagenesis. To this end the 750 bp fragment of PIS1 was amplified using specific primers (Table 2), one containing a C→T mutation yielding CAC(114)TAC. The PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) to obtain pGEM-pis1 and its sequence was confirmed. The SpeI–SphI fragment of YEpHA-PIS1 was replaced by the SpeI–SphI fragment transferred from pGEM-pis1.

Table 2. Primers used in the present study.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PIS1Not1 | 5′-ATTGCGGCCGCAGTTCGAATTCACTGGC CGTCGTT-3′ |

| PIS1Not2 | 5′-ATTGCGGCCGCGCATCTTGTACTATCACA CTTTCCC-3′ |

| PIS1M1 | 5′-GGGCTTGGATATTACTAGTTACTACATGC-3′ |

| PIS1M2 | 5′-TACCGCTGGCTTGATGTG-3′ |

Cell extracts and immunoblot analyses

To study the level of Pis1p, cell extracts were prepared by alkaline lysis [33]. Proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE and the HA–Pis1 and HA–Rsp5 tagged proteins were revealed using the monoclonal mouse anti-HA antibody 16B12 (BabCO). Rabbit anti-Hts1p antibody (a gift from T. Mason, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Massachusetts, MA, U.S.A.) was used as a control. CAT was visualized using a rabbit monoclonal anti-CAT antibody (Promega). Primary antibodies were detected with goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences).

Lipid analyses

Lipid extracts of MK1 and MK15 strains bearing an empty plasmid or plasmid YEpHA-PIS1 were prepared from approx. 2×109 (phospholipids) or 2×108 (total fatty acids) yeast cells, grown as described. Cells were harvested, washed with distilled water, suspended in 1 ml of cold water and shock-frozen. They were lysed by vigorous shaking with 500 μl of glass beads (diameter 0.3–0.4 mm; Sigma) using Mini-BeadBeater™ (Biospec Products) for 1 min at 5000 rev./min. Cell lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v). The organic phase was evaporated and the lipids were dissolved in 100 μl of chloroform/methanol (1:1). Phospholipids were resolved on precoated LK5 silica gel plates (Whatmann) using chloroform/ethanol/water/triethylamine (30:35:7:35, by vol.) as the mobile phase. They were visualized under UV after vaporization with a primuline solution [0.05 mg/ml in acetone/water (80:20, v/v)] and identified using appropriate standards. Phospholipids were scraped from the plate. Fatty acid methyl esters either of total fatty acids or of phospholipids were obtained as described by Ferreira et al. [34]. Briefly, cell lipid extracts or the various phospholipids were eluted from the silica with chloroform/methanol/water (5:5:1, by vol.) and transesterification was carried out by heating the eluate at 50 °C for 16 h in 2% (v/v) H2SO4 in dry methanol. The resulting fatty acid methyl esters were extracted with hexane and analysed by gas chromatography using a 25 mm×0.32 mm AT-1 capillary column (Alltech), with heptadecanoicmethyl ester as the standard. Fatty acids were quantified and used to calculate the amount of lipid in each class. The specific lipid content was finally expressed as a percentage of total lipids. For the data presented in Figures 7 and 8 the significance of differences between the lipid species was assessed by the ANOVA test, using the GraphPad Prism software (P<0.05). This test is appropriate for comparing means for three or more variables.

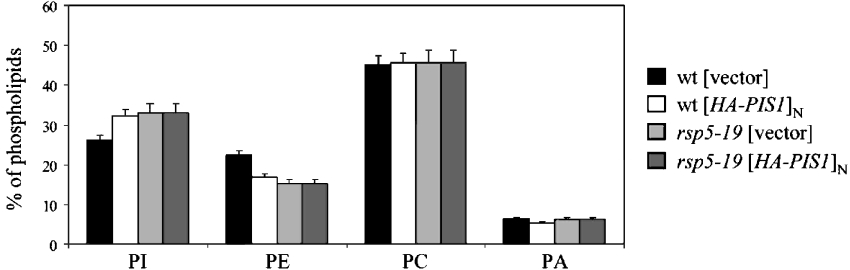

Figure 7. The rsp5-19 mutation, and PIS1 overexpression affect the PI/PE ratio.

Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains both transformed with vector or plasmid YEpHA-PIS1 were grown at 33 °C for 21 h. The level of each phospholipid was determined and is presented as a percentage of total phospholipids. Values are means±S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments. Significance of differences was examined by ANOVA (P<0.05, n=3).

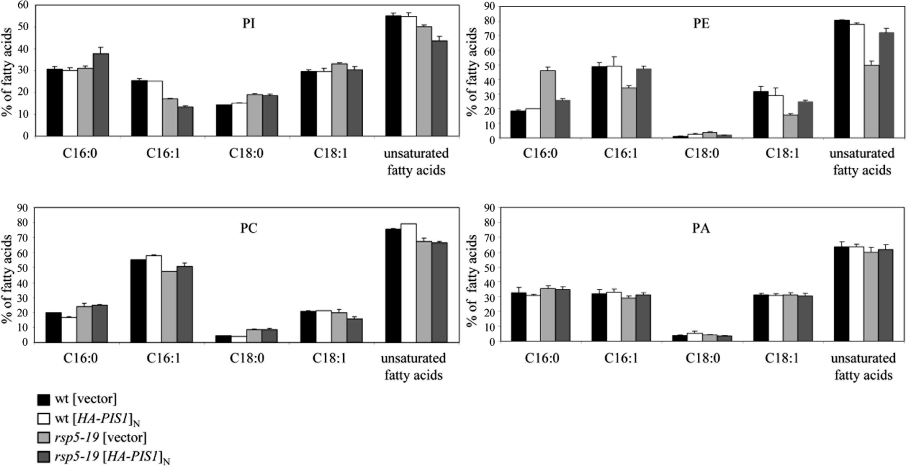

Figure 8. Overexpression of PIS1 in the rsp5-19 mutant promotes incorporation of saturated fatty acids into PI and restores wild-type fatty acid composition in PE.

Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains both transformed with vector or plasmid YEpHA-PIS1 were grown at 33 °C for 21 h. The fatty acid distribution in PI, PE, PC and PA were determined and are shown as a percentage of total fatty acids in the indicated phospholipid. Values are means±S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance of differences was examined by ANOVA (P<0.05, n=3).

β-Galactosidase assays

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously [35]. β-Galactosidase activity A (given as O-naphthol nmol/min per mg of protein, measured at 420 nm) was calculated as follows: A=(A420×100×1700)/(4.5×V×c×t), where V is the volume of the protein extract (ml), c is the protein concentration (mg/ml) and t is the incubation time (min) at 30 °C.

RESULTS

PIS1 is a multicopy suppressor of rsp5 mutations

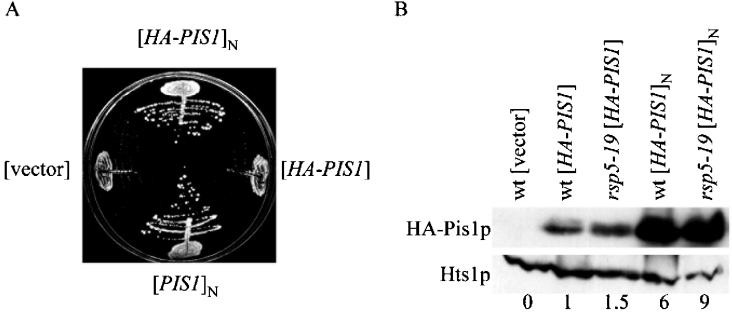

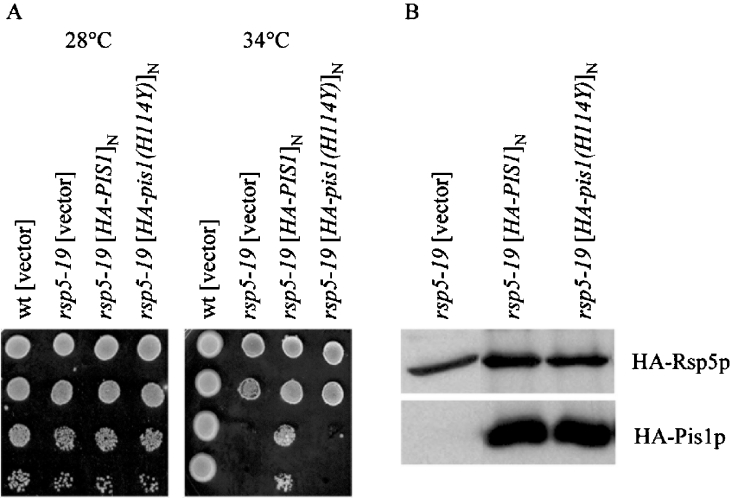

Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase takes part in many cellular processes. To better understand the role of Rsp5p and its influence on various biosynthetic and regulatory pathways, a screen of multicopy rsp5-9 suppressors was performed [30]. Among the many suppressor genes encoding ubiquitin, the CCT6 gene encoding one of the subunits of the Cct chaperonin was identified [30]. Here we analysed a plasmid isolated in the same screen, bearing a fragment of DBF2 along with the MRD1 and PIS1 genes. Deletion analyses revealed that the PIS1 gene encoding Pis1p was responsible for the suppression of the rsp5-9 ts growth defect. This suppression was allele-non specific since the overexpressed PIS1 gene suppressed all of the alleles tested: rsp5-w2, rsp5-9, rsp5-19, rsp5-w3 and rsp5-17 (expressed on two different genetic backgrounds), which contained point mutations causing amino acid substitutions in various WW domains (rsp5-w2, W359F, P362A in WW2; rsp5-9, P418S; rsp5-19, P418L; rsp5-w3, W415F and P418A in WW3) or the Hect domain (rsp5-17/mdp1-1; P784T) and conferred the ts growth defect [31,36,37] (Figure 1A, and results not shown). Overproduction of PIS1 also allowed germination and several divisions of rsp5Δ spores at 23 °C on complete medium without oleic acid addition (results not shown). Furthermore, the HA–PIS1 gene on the multicopy plasmid that expressed N-terminally tagged Pis1p was also active as a suppressor of rsp5-19 (Figure 1A). This YEpHA-PIS1 plasmid fully complemented the normally lethal pis1Δ allele [24]. Complementation was tested by transformation of heterozygous PIS1/pis1Δ diploid, sporulation and tetrad analysis (results not shown). However, the HA–PIS1 tagged version expressed from a single copy plasmid did not suppress the rsp5-19 mutation (Figure 1A), indicating that the copy number of the plasmid, and therefore high cellular levels of Pis1p are probably important for suppression.

Figure 1. Overexpression of PIS1 from a multicopy plasmid improves the growth of the rsp5-19 mutant at an elevated temperature.

(A) Growth of the rsp5-19 expressing vector, [vector]; HA–PIS1 from the single copy plasmid, [HA–PIS1]; PIS1 from the multicopy plasmid, [PIS1]N, and HA–PIS1 from the multicopy plasmid, [HA–PIS1]N, on YEPD after 2 days incubation at 34 °C. (B) Western blot analysis of cellular extracts of the wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains bearing the vector, the single copy plasmid YCpHA-PIS1 or the multicopy plasmid YEpHA-PIS1 was performed. Anti-HA antibody and anti-Hts1p antibody (protein loading control) was used. The numbers below the blot represent the ratio of the HA–Pis1p level in each strain compared with the level of HA–Pis1p in the wild-type strain expressing the YCpHA-PIS1 plasmid.

PIS1 suppression of rsp5 is related to cellular level of Pis1p

Cellular levels of Pis1p were analysed by Western blotting in the wild-type and rsp5-19 backgrounds using HA–PIS1 expressed from either single or multicopy plasmids. The respective transformants were grown at 30 °C and protein extracts were prepared. There was a 6-fold higher level of Pis1p in strains bearing the multicopy plasmid YEpHA-PIS1 as compared with strains bearing the single copy plasmid YCpHA-PIS1 (Figure 1B). In addition, the level of Pis1p was about 1.5-fold higher in the rsp5-19 mutant strain than in the wild-type strain. These results indicate that a very high level of Pis1p is important for suppression and that PIS1 expression is elevated in the rsp5-19 background.

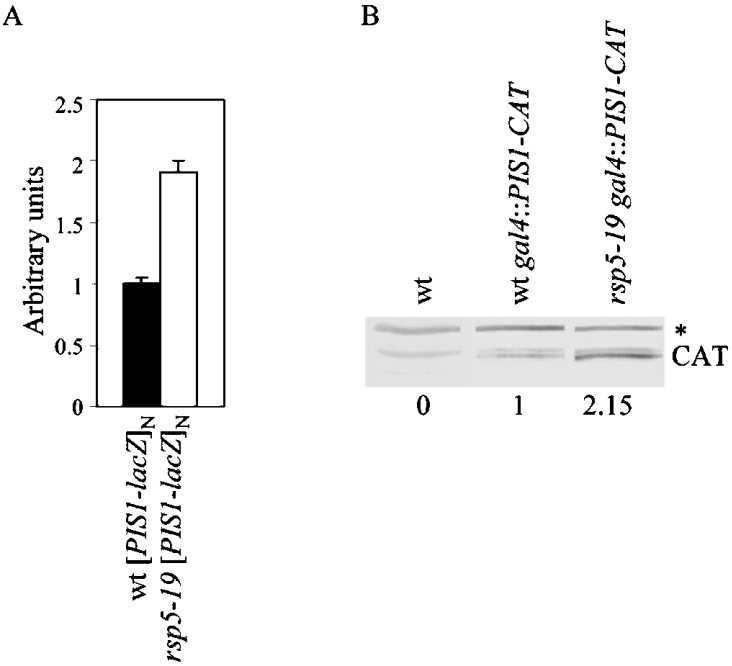

To verify whether PIS1 expression is regulated at the translational or transcriptional level in the rsp5 strain, transcriptional reporter fusions were introduced into wild-type and rsp5-19 backgrounds using a multicopy plasmid bearing a PIS1–lacZ fusion gene (pMA109) or an integrative plasmid bearing a PIS1–CAT fusion reporter gene (p911). β-galactosidase activity was measured and the level of CAT was determined by Western blotting (Figure 2, A and B). At the transcriptional level PIS1 was increased approx. 2-fold in rsp5-19 mutant strains as compared with the wild-type strain, whatever the reporter system used, when cells were grown on glucose medium (Figure 2, A and B and results not shown). It was also higher in rsp5 cells than in wild-type cells grown in a galactose-containing medium (results not shown), a carbon source known to induce PIS1 transcription [26]. From these results, we conclude that rsp5-19 affects the regulation of PIS1 expression at the transcription level.

Figure 2. Expression of the PIS1 gene is increased in the rsp5-19 mutant strain.

(A) Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains expressing [PIS1–lacZ]N from the multicopy plasmid were grown on SD+cas medium, extracts were prepared and the activity of β-galactosidase was compared. Values are means±S.D. of at least 3 independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains expressing the PIS1–CAT cassette integrated into the gal4 locus. A specific anti-CAT antibody was used. The nonspecific protein (*) which was also recognized by the anti-CAT antibody was used as a loading control. Quantification of CAT is shown below the blot and represents the ratio of CAT level in rsp5-19 over the level of CAT in the wild-type strain expressing PIS1–CAT.

Pis1p catalytic activity is essential for suppression

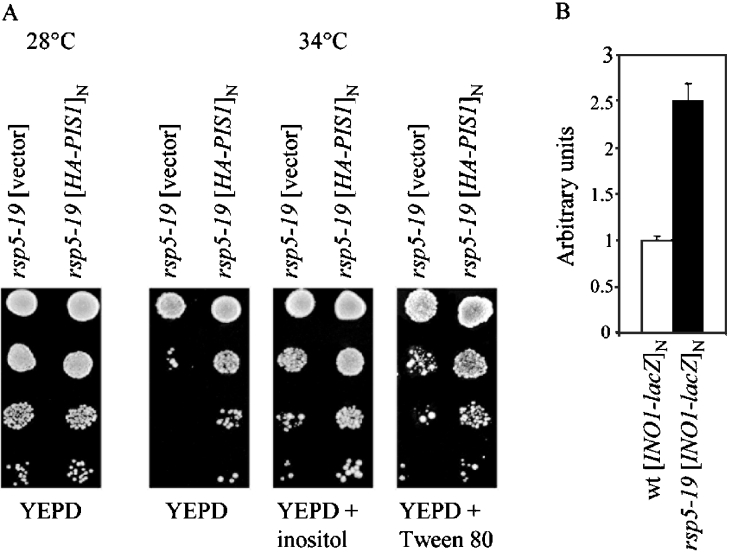

To investigate if the catalytic activity of Pis1p is essential for suppression, a multicopy plasmid containing the HA–pis1(H114Y) mutant allele was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. This allele causes an amino acid substitution in Pis1p previously shown to result in almost complete (0.2% of wild-type levels) loss of catalytic activity [38]. Interestingly, this plasmid did not suppress the growth defects of the rsp5-19 strain (MK15) even though the Pis1p(H114Y) was synthesized at similar levels as Pis1p (Figure 3, A and B). Therefore a high level of active Pis1p overexpression is necessary for suppression of rsp5-19 and it can be proposed that overproduction of PI, the product of Pis1p, may help rsp5 cells to grow at elevated temperatures.

Figure 3. YEpHA-pis1(H114Y) does not suppress the rsp5-19 ts phenotype.

(A) Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains were transformed with vector or multicopy plasmids carrying HA–PIS1 or HA-pis1(H114Y). Serial dilutions (1:10-fold) of transformants were spotted on to YEPD plates and grown at the indicated temperatures for 2 days. (B) Western blot analysis of cell extracts of the rsp5-19 strain bearing the vector or the multicopy plasmids, YEpHA-PIS1 or YEpHA-pis1(H14Y). Anti-HA antibody recognizing HA–Pis1p and HA–Rsp5p (loading control) was used.

Addition of inositol to the medium improves growth of the rsp5-19 strain, and expression of the INO1 gene is upregulated in the rsp-19 strain

In PI synthesis Pis1p utilizes CDP-DAG (CDP-diacylglycerol) and inositol as substrates [2]. Supplementation of yeast cells with inositol increases the cellular level of PI because the Km of Pis1p for this substrate is much higher than the intracellular inositol concentration resulting from endogenous synthesis [39]. Therefore we tested the growth of the rsp5-19 strain at 34 °C on a medium supplemented with 20 mg/l inositol. This temperature was chosen, since it is the optimal temperature for rsp5-19 suppression by PIS1 in the MK15 strain. As shown in Figure 4(A), inositol that was added to the medium improved the growth of the rsp5-19 mutant at a restrictive temperature, to the same extent as overexpression of PIS1, and in a similar way as did medium supplemented with Tween-80 that was used as source of unsaturated fatty acid (namely oleic acid). Since a high inositol concentration in the medium results in increased PI synthesis [39], we postulate that the addition of inositol may restore the growth of rsp5-19 in a similar manner as does overexpression of PIS1.

Figure 4. Addition of inositol to the medium improves growth of the rsp5-19 strain and expression of INO1 is increased in the rsp5-19 strain.

(A) The rsp5-19 strain was transformed with the vector or the multicopy plasmid carrying HA–PIS1. Serial dilutions (1:10 steps) of transformants were spotted on to YEPD, YEPD+inositol (20 mg/l), YEPD+Tween-80 (1%) and allowed to grow at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (B) Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 strains expressing INO1–lacZ from the multicopy plasmid were grown on SC-ura-inositol medium, extracts were prepared and the activity of β-galactosidase was compared. Values are means±S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments.

In the cell, inositol phosphate is produced by inositol phosphate synthase encoded by INO1 [2]. Since addition of inositol to the medium improved the growth of the rsp5-19 strain, we postulated that the expression of INO1 could be increased in the rsp5-19 strain, as is the expression of PIS1. The level of INO1 transcription was analysed using the multicopy plasmid pJH359 expressing a INO1–lacZ fusion reporter gene in cells grown in SC-ura-inositol. The β-galactosidase activity was 2.5-fold higher in the rsp5-19 strain compared with the wild-type strain (Figure 4B) indicating that INO1 transcription was indeed increased in the rsp5-19 background. Thus the expression of both INO1 and PIS1, encoding two enzymes in the PI biosynthetic pathway, is enhanced in the rsp5-19 strain.

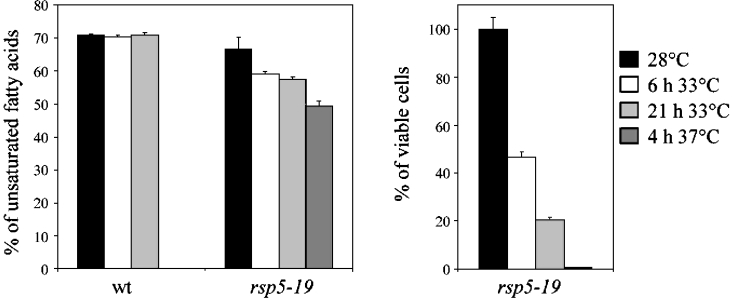

Overexpression of PIS1 does not restore wild-type fatty acid patterns in the rsp5-19 strain

An essential function of Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is to regulate the expression of OLE1, encoding fatty acid desaturase [11,12,17]. Thus one of the effects of the rsp5-19 mutation might be to lower unsaturated fatty acid levels and consequently to induce accumulation of saturated fatty acids in the cell. We therefore studied whether accumulation of saturated fatty acids correlated with the survival of the rsp5-19 strain at elevated temperatures. In S. cerevisae, C16:1 (palmitoleic acid) and C18:1 (oleic acid) are the main unsaturated species, whereas C16:0 (palmitic acid) and C18:0 (stearic acid) are the most abundant saturated fatty acids [40]. Under normal aerobic conditions fatty acids are mainly unsaturated in yeast, since the percentage unsaturation ratio (i.e. the unsaturated forms as a percentage of total fatty acids) of major complex lipids is about 70–80% [40]. In the experiment presented in Figure 5, rsp5-19 cells were grown at the permissive temperature (28 °C) for 16 h and transferred to 33 °C for 6 or 21 h or for 4 h to the more restrictive temperature, 37 °C. Interestingly, the percentage of unsaturated fatty acids in the rsp5-19 strain dropped from 65% at 28 °C to values below 60% when cells were incubated at 33 °C, and to 50% when cells were grown at 37 °C (Figure 5). Simultaneously, survival dropped to 45 or 20% when cells were incubated at 33 °C for 6 or 21 h respectively. No cells were viable after incubation for 4 h at 37 °C. A control experiment in which wild-type cells were grown at 28 °C and transferred to 33 °C for 6 or 21 h constantly, showed 70% unsaturated fatty acids. Cells require unsaturated fatty acids for survival [11] and saturated fatty acid accumulation is deleterious to yeast [4]. The results of our experiments suggest a correlation between the accumulation of saturated fatty acids and rsp5-19 cell lethality at 33 °C. This is supported by the observation that cell growth can be restored at this temperature when Tween-80, used as source of unsaturated fatty acid (namely oleic acid), is added to the medium (Figure 4A); hence, this phenomenon, similar to the recently demonstrated effect of rsp5 on nuclear transport of RNA [21], could provide at least a partial explanation for the lethality of rsp5-19 cells at elevated temperatures.

Figure 5. Accumulation of saturated fatty acids in rsp5-19 correlates with cell viability at elevated temperatures.

Wild-type (wt) and rsp5-19 cells were grown to stationary phase at 28 °C, then diluted to an attenuance of approx. 0.5, incubated for 2 h at 28 °C, 6 h at 33 °C, 21 h at 33 °C or 4 h at 37 °C (rsp5-19 only). The level of unsaturated fatty acids was measured. Values are means±S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments. Samples from cultures were plated on to YEPD medium, incubated for 2 days and the colonies counted.

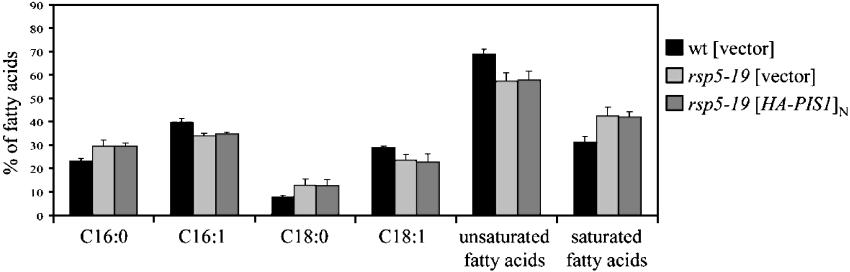

A possible explanation for rsp5-19 suppression by overexpression of PIS1 was the restoration of a wild-type-like unsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio. To test this possibility, the total fatty acid content was determined in the rsp5-19 mutant strain, in the rsp5-19 mutant overexpressing PIS1 and in the congenic wild-type strain, used as a reference. Cells were grown at 28 °C and transferred to 33 °C for 21 h. These conditions were chosen after growth and viability tests establishing the optimum suppressive effect of PIS1 overexpression on the rsp5-19 mutant. Total unsaturated fatty acid levels and the amount of individual fatty acids in these three strains were determined. As shown in Figure 6, at a non-permissive temperature the rsp5-19 mutation led to an increase in saturated fatty acids (C16:0 and C18:0) at the expense of unsaturated forms, as compared with the wild-type strain. Interestingly, this fatty acid composition was observed in rsp5-19 cells, irrespective of PIS1 overexpression (Figure 6). From these results, we conclude that overexpression of PIS1 does not restore the wild-type fatty acid composition in rsp5-19.

Figure 6. Overexpression of PIS1 does not change the fatty acid distribution in rsp5-19 cells.

The rsp5-19 strain transformed with the vector or the multicopy plasmid bearing HA–PIS1, and wild-type strain (wt) transformed with the vector were grown at 33 °C for 21 h. The levels of various fatty acids were determined and are presented as a percentage of total fatty acids. Values are means±S.D. for at least 3 independent experiments.

The rsp5-19 mutation and PIS1 overexpression in the wild-type strain affect the PI/PE (phosphatidylethanolamine) ratio

We expected overexpression of PIS1 to result in PI accumulation in the cells. To test this, phospholipid analyses were performed in wild-type and rsp5-19 cells, with or without PIS1 overexpression. Indeed, the level of PI increased in the wild-type strain overexpressing PIS1 (compare wild-type [vector] with wild-type expressing the multicopy plasmid [HA–PIS1]N in Figure 7). Surprisingly, PI was increased to the same extent in the rsp5-19 mutant (rsp5-19 [vector], Figure 7). This was possibly due to the higher transcriptional activation of genomic PIS1 observed in this background (see Figure 2). Furthermore, the overexpression of PIS1 from a multicopy plasmid did not cause a further increase in PI levels in the rsp5-19 strain (rsp5-19 [HA–PIS1]N, Figure 7). All strains with increased levels of PI showed decreased levels of PE. This observation is to be expected since Pis1p competes for the common substrate CDP-DAG with PS (phosphatidylserine) synthase (Cho1p), whose product, PS, is directly converted into PE by PS decarboxylase (Psd1p and Psd2p) [2]. The amounts of PC (phosphatidylcholine) and PA (phosphatidic acid) were similar in all strains analysed (Figure 7). It should be noted that since the amount of PS was very low under our experimental conditions, it could not be determined. These results indicate that overexpression of PIS1 causes an increase in the amount of PI at the expense of PE in the wild-type strain and that the increased PI level in rsp5-19 is possibly a regulatory adaptation of cells to physiological changes caused by this mutation. However, the presence of additional copies of the PIS1 gene in rsp5-19, which improves the growth of this mutant at 33 °C, does not result in a further increase in the amount of PI, implying that an increased PI level per se is not responsible for suppression.

Overexpression of PIS1 in the rsp5-19 mutant favours saturated fatty acid incorporation into PI and restores wild-type fatty acid composition in PE

The next step towards understanding the mechanism of rsp5 suppression by PIS1 was to investigate whether the rsp5-19 mutation and/or overexpression of PIS1 might affect saturated fatty acid distribution among the various phospholipids. To this end, the fatty acid composition of phospholipids was determined in the wild-type [vector], wild-type [HA–PIS1]N, rsp5-19 [vector] and rsp5-19 [HA–PIS1]N strains, grown for 21 h at 33 °C. Overexpression of PIS1 in wild-type strain essentially did not change the fatty acid composition of any of the phospholipids analysed: PI, PE, PC and PA (Figure 8). Thus whereas overexpression of PIS1 in the wild-type background significantly affects the PI/PE ratio (see Figure 7), it does not influence the overall fatty acid content of these phospholipids. Strikingly, the rsp5-19 mutation resulted in a specific, dramatic increase of saturated fatty acyl chains at the expense of unsaturated forms in PE, and to a lesser extent in PC (rsp5-19 [vector], Figure 8). Overexpression of PIS1 in this background (rsp5-19 [HA–PIS1]N, Figure 8), induced recovery of the unsaturation ratio in PE to a level very similar to that in the wild-type strain. Importantly, the decrease in C16:0 content in PE, observed when PIS1 is overexpressed, could be related to a low but significant increase in C16:0 content in PI at the expense mainly of the C16:1 species. Altogether, these results suggest that the rsp5-19 mutation induces saturated fatty acid accumulation in PE, a phenomenon that can be fully suppressed by overexpression of PIS1, due to rerouting of these saturated forms towards PI.

DISCUSSION

The synthesis of fatty acids, phospholipids, dolichols and sterols in response to nutrient availability and cellular needs is highly regulated and is co-ordinated to build and maintain properly composed cellular membranes [2,41]. In particular, unsaturated fatty acids are crucial determinants of membrane fluidity since they regulate packing of phospholipids. Hence, the main enzyme involved in fatty acid desaturation in yeast, the Δ-9 fatty acid desaturase Ole1p is essential for growth, unless the cells are cultivated in the presence of an exogenous unsaturated fatty acid such as oleate. Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is involved in the regulation of OLE1. Consequently, rsp5Δ mutants display an auxotrophy for oleate [11]. This shows that when a decrease in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis is combined with other effects related to rsp5 mutations it has a pernicious effect on growth.

In a search for multicopy suppressors of rsp5 mutations, we isolated the PIS1 gene, encoding PI synthase. Pis1p is essential in yeast since it is the only enzyme that catalyses the synthesis of PI from CDP-DAG and inositol. We demonstrated that the loss of viability of the rsp5-19 mutant at increasing non-permissive temperatures correlates with the decrease in the unsaturation/saturation ratio of fatty acids i.e. accumulation of saturated forms at the expense of unsaturated species. However, overexpression of PIS1 did not result in recovery of wild-type cellular fatty acid composition: in the presence of high levels of Pis1p, the rsp5-19 mutation still caused a dramatic decrease in the level of unsaturated fatty acids. This result was somewhat expected if one considers the catalytic function of Pis1p, and suggests that the suppression of rsp5 mutations by overexpression of PIS1 is directly related to PI biosynthesis. Several observations are consistent with this assumption. First, we demonstrated that the catalytic activity of Pis1p is essential for suppression. Second, the rsp5-19 mutation was suppressed by the addition of inositol into the medium; it had already been shown that cells grown in medium supplemented with inositol synthesize more PI [39]. Third, we show that PIS1 is upregulated on the rsp5-19 background (with a 2-fold increase in transcription and a 1.5-fold increase in protein-amount compared with wild-type). This increase is accompanied by the induction of INO1 (2.5-fold), encoding Ino1p. Ino1p is involved in the synthesis of inositol-1-phosphate which after dephosphorylation serves as the Pis1p substrate in PI synthesis. Altogether, these results suggest that high levels of Pis1p (PIS1 expressed from a multi- but not a single-copy plasmid) and PI synthesis are essential for the suppression of rsp5 mutations.

Direct involvement of Rsp5p in INO1 and PIS1 regulation remains an open question. INO1 is a highly regulated gene, the regulation of which has a major impact on phospholipid metabolism [2]. It is regulated by the Ino2p–Ino4p transcription factor complex and the Opi1 repressor in response to inositol and choline. The metabolic signal for this regulatory event is the level of PA, a common precursor molecule for the biosynthesis of phospholipids, which is detected by Opi1p in the endoplasmic reticulum [42,43]. A drop in the PA level causes Opi1p to translocate to the nucleus and perform its repressor function. In our experiments, we observed an upregulation of INO1 under conditions in which inositol was absent from the medium. This could cause an increase in inositol levels in rsp5 cells. Similarly, other genes that are dependent on the Ino2p–Ino4p complex and affect choline levels, might also be upregulated, but this requires further studies. Although most phospholipid biosynthetic genes are regulated at the transcriptional level in response to inositol and choline, PIS1 is insensitive to their presence in the medium [26,44]. PIS1 is a modestly regulated gene; its transcription is increased (2–2.5)-fold at most in various mutants and growth conditions [27,45]. A recent genomic screen aimed at characterizing mutations that affect PIS1 expression identified 120 genes [45]. Among them were genes involved in chromatin silencing, DNA repair and many pex mutant genes which alter peroxisome biogenesis and function [45]. This indicated that changes within peroxisomes, potentially due to alteration in fatty acid metabolism, result in the fluctuation of PIS1 expression. RSP5 was not recovered from this screen, which was restricted to non-essential genes. Thus although Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase is known to regulate the transcriptional regulators Spt23p, Mga2p and Gln3p [11,17,46], nothing is known about its effects on transcription factors that regulate PIS1 or INO1 expression. Therefore it is possible that the induction of INO1 and PIS1 gene expression in rsp5 mutants is caused by the prevention of unsaturated fatty acids synthesis rather than by a direct regulatory effect of Rsp5p.

A high flux in phospholipid synthesis towards PI formation is probably essential for the suppression of the rsp5 mutant, yet an increased PI level does not alone account for suppression. Indeed, despite a significant increase in Pis1p level (1.5-fold in the rsp5-19 strain, 6-fold in the wild-type strain overexpressing PIS1 and 9-fold in the rsp5-19 strain overexpressing PIS1), the overall level of PI did not change proportionally in rsp5 strains. However, it is noteworthy that in all these strains, the amount of PI was increased at the expense of PE.

A possible explanation for rsp5-19 suppression by PIS1 overexpression came from analysis of the fatty acyl content of the main phospholipids. The percentage of unsaturated/saturated fatty acids incorporated into PE was 80% in wild-type and 50% in the rsp5-19 mutant at restrictive temperatures. Upon overexpression of PIS1 this ratio in rsp5-19 was restored to that observed in the wild-type strain. Concomitantly, saturated fatty acids preferentially substituted PI, facilitating safe storage of the detrimental excess of saturated fatty acids. In addition to inositol, Pis1p requires CDP-DAG as a substrate and competes for it with PS synthase (Cho1p) which supplies PS for synthesis of PE and PC [2]. It is known that PI is the most saturated phospholipid [34,47] and it was postulated that Pis1p has a higher affinity for CDP-DAG when esterified with saturated fatty acids, than with unsaturated fatty acids [47]. Therefore a significant increase in the level of Pis1p may result in specific rerouting of CDP-DAG with saturated fatty acids towards PI. Under these conditions, relatively more CDP-DAG esterified with unsaturated fatty acids could be preferentially incorporated into PS and further into PE, restoring the unsaturation/saturation ratio of this latter phospolipid. Indeed, it has already been postulated that PI may act as a buffer for saturated fatty acids in conditions of impaired unsaturated fatty acid synthesis i.e. haem depletion [34]. These results suggest that PIS1 overexpression, may improve the growth of rsp5 mutants possibly by preventing a deleterious accumulation of saturated fatty acids in PE which in the wild-type strain is esterified to 80% with unsaturated fatty acyl chains [34,47]. Moreover, decreasing the unsaturation/saturation ratio may well be detrimental to several essential cellular processes in which PE is known to be involved, such as mitochondrial integrity and function [48], membrane protein topology [49], or association of proteins into lipid rafts [50].

Finally, it is noteworthy that PI is an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathways of essential molecules, such as sphingolipids and PI phosphates, which play important regulatory roles in the cell and that could be changed in rsp5 mutants and upon PIS1 overexpression. Consistently, the C2 domain of the Rsp5p ubiquitin ligase binds phosphoinositides. Mutations in this domain that inhibit phosphoinositide-binding abolish interactions of Rsp5p with specific endosomal membranes with, as a result, perturbation of multivesicular body sorting of the biosynthetic cargo [16]. However, PIS1 suppression of rsp5 mutations by an enhanced level of phosphoinositides is not the most likely hypothesis. Indeed, the rsp5 mutant, devoid of the C2 domain is fully viable, suggesting that binding of phosphoinositide is not required for the essential functions of Rsp5p [16]. These various aspects, which should provide additional information about the link between Rsp5p and lipid homoeostasis, are presently under investigation in our respective laboratories.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Lopes (Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University, MI, U.S.A.) and S. Henry (Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, NY, U.S.A.) for plasmids, M. Kwapisz (IBB PAS) for strain and A.-L. Haenni (Institute J. Monod, Paris, France) for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the State Committee for Scientific Research of Poland grant number 3P04B01624 to T.Z., a travel grant ‘Collaborative Experimental Scholarships for Central and Eastern Europe’ from FEBS to P.K. and grants from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, France and the CNRS to T.B.

References

- 1.Schneiter R., Kohlwein S. D. Organelle structure, function, and inheritance in yeast: a role for fatty acid synthesis? Cell. 1997;88:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carman G. M., Henry S. A. Phospholipid biosynthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and interrelationship with other metabolic processes. Prog. Lipid Res. 1999;38:361–399. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(99)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ntambi J. M. Regulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase by polyunsaturated fatty acids and cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:1549–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart L. C., Yaffe M. P. A role for unsaturated fatty acids in mitochondrial movement and inheritance. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:1249–1257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carratu L., Franceschelli S., Pardini C. L., Kobayashi G. S., Horvath I., Vigh L., Maresca B. Membrane lipid perturbation modifies the set point of the temperature of heat shock response in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:3870–3875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stukey J. E., McDonough V. M., Martin C. E. Isolation and characterization of OLE1, a gene affecting fatty acid desaturation from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:16537–16544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasconcelles M. J., Jiang Y., McDaid K., Gilooly L., Wretzel S., Porter D. L., Martin C. E., Goldberg M. A. Identification and characterization of a low oxygen response element involved in the hypoxic induction of a family of Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes. Implications for the conservation of oxygen sensing in eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14374–14384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez C. I., Martin C. E. Fatty acid-responsive control of mRNA stability. Unsaturated fatty acid-induced degradation of the Saccharomyces OLE1 transcript. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25801–25809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.25801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi J. Y., Stukey J., Hwang S. Y., Martin C. E. Regulatory elements that control transcription activation and unsaturated fatty acid-mediated repression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae OLE1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:3581–3589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S., Skalsky Y., Garfinkel D. J. MGA2 or SPT23 is required for transcription of the delta9 fatty acid desaturase gene, OLE1, and nuclear membrane integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:473–483. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppe T., Matuschewski K., Rape M., Schlenker S., Ulrich H. D., Jentsch S. Activation of a membrane-bound transcription factor by regulated ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent processing. Cell. 2000;102:577–586. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shcherbik N., Żołądek T., Nickels J. T., Haines D. S. Rsp5p is required for ER bound Mga2p120 polyubiquitination and release of the processed/tethered transactivator Mga2p90. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakagawa Y., Sakumoto N., Kaneko Y., Harashima S. Mga2p is a putative sensor for low temperature and oxygen to induce OLE1 transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:707–713. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandasamy P., Vemula M., Oh C. S., Chellappa R., Martin C. E. Regulation of unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces: the endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein, Mga2p, a transcription activator of the OLE1 gene, regulates the stability of the OLE1 mRNA through exosome-mediated mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36586–36592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingham R. J., Gish G., Pawson T. The Nedd4 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: functional diversity within a common modular architecture. Oncogene. 2004;23:1972–1984. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn R., Klos D. A., Adler A. S., Hicke L. The C2 domain of the Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase binds membrane phosphoinositides and directs ubiquitination of endosomal cargo. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:135–144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shcherbik N., Kee Y., Lyon N., Huibregtse J. M., Haines D. S. A single PXY motif located within the carboxyl terminus of Spt23p and Mga2p mediates a physical and functional interaction with ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53892–53898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotin D., Staub O., Haguenauer-Tsapis R. Ubiquitination and endocytosis of plasma membrane proteins: role of Nedd4/Rsp5p family of ubiquitin-protein ligases. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;176:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00232001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck T., Schmidt A., Hall M. N. Starvation induces vacuolar targeting and degradation of the tryptophan permease in yeast. J. Cell. Biol. 1999;146:1227–1238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaudenon S. L., Huacani M. R., Wang G., McDonnell D. P., Huibregtse J. M. Rsp5 ubiquitin-protein ligase mediates DNA damage-induced degradation of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:6972–6979. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gwizdek C., Hobeika M., Kus B., Ossareh-Nazari B., Dargemont C., Rodriguez M. S. The mRNA nuclear export factor Hpr1 is regulated by Rsp5-mediated ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13401–13405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann S., Petfalski E., Brugger B., Grosshans H., Wieland F., Tollervey D., Hurt E. Formation and nuclear export of tRNA, rRNA and mRNA is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1156–1162. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwapisz M., Cholbinski P., Hopper A. K., Rousset J.-P., Żołądek T. Rsp5p dependent ubiquitination modulates translation accuracy in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae. RNA. 2005;11:1710–1718. doi: 10.1261/rna.2131605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikawa J., Kodaki T., Yamashita S. Primary structure and disruption of the phosphatidylinositol synthase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:4876–4881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:3–41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50954-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson M. S., Lopes J. M. Carbon source regulation of PIS1 gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae involves the MCM1 gene and the two-component regulatory gene, SLN1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26596–26601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardocki M. E., Lopes J. M. Expression of the yeast PIS1 gene requires multiple regulatory elements including a Rox1p binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38646–38652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scafe C., Chao D., Lopes J., Hirsch J. P., Henry S., Young R. A. RNA polymerase II C-terminal repeat influences response to transcriptional enhancer signals. Nature (London) 1990;347:491–494. doi: 10.1038/347491a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stettler S., Chiannilkulchai N., Hermann-Le Denmat S., Lalo D., Lacroute F., Sentenac A., Thuriaux P. A general suppressor of RNA polymerase I, II and III mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1993;239:169–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00281615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabir M. A., Kamińska J., Segel G. B., Bethlendy G., Lin P., Della S. F., Blegen C., Swiderek K. M., Żołądek T., Arndt K. T., Sherman F. Physiological effects of unassembled chaperonin Cct subunits in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2005;22:219–239. doi: 10.1002/yea.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajewska B., Kamiń;ska J., Jesionowska A., Martin N. C., Hopper A. K., Żołądek T. WW domains of Rsp5p define different functions: determination of roles in fluid phase and uracil permease endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;157:91–101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gietz R. D., Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volland C., Urban-Grimal D., Geraud G., Haguenauer-Tsapis R. Endocytosis and degradation of the yeast uracil permease under adverse conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9833–9841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreira T., Regnacq M., Alimardani P., Moreau-Vauzelle C., Berges T. Lipid dynamics in yeast under haem-induced unsaturated fatty acid and/or sterol depletion. Biochem. J. 2004;378:899–908. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordier H., Karst F., Berges T. Heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA encoding mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;39:953–967. doi: 10.1023/a:1006181720100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Żołądek T., Tobiasz A., Vaduva G., Boguta M., Martin N. C., Hopper A. K. MDP1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene involved in mitochondrial/cytoplasmic protein distribution, is identical to the ubiquitin-protein ligase gene RSP5. Genetics. 1997;145:595–603. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamińska J., Gajewska B., Hopper A. K., Żołądek T. Rsp5p, a new link between the actin cytoskeleton and endocytosis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:6946–6948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.6946-6958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumano Y., Nikawa J. Functional analysis of mutations in the PIS1 gene, which encodes Saccharomyces cerevisiae phosphatidylinositol synthase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995;126:81–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley M. J., Bailis A. M., Henry S. A., Carman G. M. Regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by inositol. Inositol is an inhibitor of phosphatidylserine synthase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:18078–18085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuller G., Nemec T., Hrastnik C., Daum G. Lipid composition of subcellular membranes of an FY1679-derived haploid yeast wild-type strain grown on different carbon sources. Yeast. 1999;15:1555–1564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1555::AID-YEA479>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenberg M. L., Lopes J. M. Genetic regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.1-20.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loewen C. J., Gaspar M. L., Jesch S. A., Delon C., Ktistakis N. T., Henry S. A., Levine T. P. Phospholipid metabolism regulated by a transcription factor sensing phosphatidic acid. Science (Washington, DC) 2004;304:1644–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1096083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loewen C. J., Roy A., Levine T. P. A conserved ER targeting motif in three families of lipid binding proteins and in Opi1p binds VAP. EMBO J. 2003;22:2025–2035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jesch S. A., Zhao X., Wells M. T., Henry S. A. Genome-wide analysis reveals inositol, not choline, as the major effector of Ino2p-Ino4p and unfolded protein response target gene expression in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9106–9118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411770200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gardocki M. E., Bakewell M., Kamath D., Robinson K., Borovicka K., Lopes J. M. Genomic analysis of PIS1 gene expression. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:604–614. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.3.604-614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crespo J. L., Helliwell S. B., Wiederkehr C., Demougin P., Fowler B., Primig M., Hall M. N. NPR1 kinase and RSP5-BUL1/2 ubiquitin ligase control GLN3-dependent transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37512–37517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneiter R., Brugger B., Sandhoff R., Zellnig G., Leber A., Lampl M., Athenstaedt K., Hrastnik C., Eder S., Daum G., et al. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) analysis of the lipid molecular species composition of yeast subcellular membranes reveals acyl chain-based sorting/remodeling of distinct molecular species en route to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:741–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgermeister M., Birner-Grunberger R., Heyn M., Daum G. Contribution of different biosynthetic pathways to species selectivity of aminoglycerophospholipids assembled into mitochondrial membranes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1686:148–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang W., Campbell H. A., King S. C., Dowhan W. Phospholipids as determinants of membrane protein topology: phosphatidylethanolamine is required for the proper topological organization of the γ-aminobutyric acid permease (GabP) of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26032–26038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Opekarova M., Malinska K., Novakova L., Tanner W. Differential effect of phosphatidylethanolamine depletion on raft proteins: further evidence for diversity of rafts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1711:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]