Abstract

US3 of human cytomegalovirus is an endoplasmic reticulum resident transmembrane glycoprotein that binds to major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and prevents their departure. The endoplasmic reticulum retention signal of the US3 protein is contained in the luminal domain of the protein. To define the endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence in more detail, we have generated a series of deletion and point mutants of the US3 protein. By analyzing the rate of intracellular transport and immunolocalization of the mutants, we have identified Ser58, Glu63, and Lys64 as crucial for retention, suggesting that the retention signal of the US3 protein has a complex spatial arrangement and does not comprise a contiguous sequence of amino acids. We also show that a modified US3 protein with a mutation in any of these amino acids maintains its ability to bind class I molecules; however, such mutated proteins are no longer retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and are not able to block the cell surface expression of class I molecules. These findings indicate that the properties that allow the US3 glycoprotein to be localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and bind major histocompatibility complex class I molecules are located in different parts of the molecule and that the ability of US3 to block antigen presentation is due solely to its ability to retain class I molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum.

The importance of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated immune responses in limiting and clearing viral infections has been well documented for a number of viral systems (7). These processes imply a balance between immune control of the virus and immune escape by the virus (33). Many viruses encode proteins that can inhibit or abolish the surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on infected cells. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which causes benign but persistent infections in immunocompetent individuals, encodes an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident glycoprotein, US3, that prevents intracellular transport of MHC class I molecules (1, 19). HCMV US3 binds physically to MHC class I heterodimers and sequesters them in the ER. This function might play a central role in establishing persistent, latent, and acute viral infections. Therefore, identifying the retention signals and elucidating the structural requirements for US3 to bind to MHC class I molecules might reveal the mechanisms of viral pathogenesis and protein compartmentalization.

The ER is a heterologous organelle containing large amounts of newly synthesized polypeptides as well as resident proteins responsible for numerous posttranslational modifications, including glycosylation, folding, and oligomerization reactions. Because of their abundance, ER resident proteins must be efficiently segregated from their substrates by specific retention and retrieval signals in their primary structure. To date, only two systems, both based on a retrieval mechanism, have been characterized. The KDEL tetrapeptide at the extreme carboxyl (COOH) terminus of ER resident proteins is a common signal for a number of luminal chaperones (30). This retrieval mechanism is based on the KDEL receptor (ERD2), which binds escaped proteins in the Golgi complex and returns them to the ER (23, 24). In the other proposed mechanism, double-lysine and presumably double-arginine motifs located in the cytoplasmic domains of several ER membrane proteins also function as retrieval motifs (18, 21). It is known that double-lysine motif-containing proteins bind the complex of cytosolic coat proteins (coatomer), COP I, and that this interaction mediates the retrieval of these proteins from the Golgi for return to the ER (35). Sequences flanking the double-lysine motif also contribute to the steady-state distribution of the proteins between the ER and the Golgi complex (17, 18).

The primary structure of the US3 protein (1) consists of a signal sequence of 15 amino acids followed by a luminal domain of 146 amino acids. Twenty membrane-spanning residues separate the luminal portion of the US3 protein from a short, 5-amino-acid cytoplasmic tail. The protein is glycosylated at amino acid 60. US3, unlike most other luminal proteins in the ER, does not contain in its primary structure either the KDEL sequence or any of its close homologues. We have shown previously that the luminal domain of the US3 protein is sufficient for retention in the ER and that the ER localization of US3 involves true retention without recycling through the Golgi (20). To characterize more precisely the sequence or structural requirement of the luminal ER retention signal of US3, we used two different approaches. In the first approach, we constructed fusions of mutated US3 luminal sequences and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and analyzed the subcellular localization of the resulting chimeric proteins. Second, we investigated whether the sequence elements identified with the first approach could mediate retention of the protein in the ER in the context of homologous US3 glycoproteins. We identified a noncontiguous sequence consisting of three specific amino acids that constitutes the retention signal of the US3 protein. Substitution of alanine for any of these amino acids led to a loss of ER retention of the chimeric reporter constructs and of the homologous US3 glycoproteins. Importantly, these mutant proteins, in contrast to wild-type US3, were unable to prevent class I molecules from reaching the plasma membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

The cDNA encoding GFP was subcloned into the SacII and BamHI restriction sites of the tetracycline-inducible expression vector pUHG10.3 (11). The cloning of US3 into the pUHG10.3 vector has been described previously (1). To generate the GFP chimeras shown in Fig. 1, DNA fragments spanning the coding sequence for different lengths of the US3 luminal domain were amplified by the PCR with pUHG10.3/US3 as a template. Appropriate oligonucleotides containing XhoI and SacII restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends were used in the reaction. Amplified fragments were digested with XhoI and SacII and ligated into the XhoI- and SacII-digested pHUG10.3/GFP. The following oligonucleotide was used as the forward primer for PCR amplification: TAACTCGAGCCACCATGAAGCCGGTGTTGGTGCT. The following reverse primers were used: Δ128GFP (ATTGGATCCCGCGGCATATTTCTTGGGG), Δ84GFP (ATTGGATCCACCGGACACCTGCAGTC), Δ74GFP (ATTGGATCCTTGAGAGACGATACCCACGTTC), Δ70GFP (ATTGGATCCACCCACGTTCACAAAGTGTTTCTC), Δ65GFP (ATTGGATCCGTGTTTCTCGGTGAAGTTGCC), Δ55GFP (ATTGGATCCCCCCTTGAAGTACAGCATGC), Δ50GFP (ATTGGATCCCATGCCCATATGGAACCAGCA), and Δ38GFP (ATTGGATCCTCGAAAGTGGGCCGATCTG). Single-amino-acid mutations were introduced by the PCR-mediated oligonucleotide-directed protocol (15) with either Δ128GFP (for mutants shown in Fig. 2 and 3) or wild-type US3 cDNA (for mutants shown in Fig. 4 to 6) as templates. The following oligonucleotides were used (substituted codons are underlined): R56A (ATGCTGTACTTCAAGGGGGCGATGTCGGGCAACTTCAC/GTGAAGTTGCCCGACATCGCCCCCTTGAAGTACAGCAT), M57A (TGTACTTCAAGGGGAGGGCGTCGGGCAACTTCACC/GGTGAAGTTGCCCGACGCCCTCCCCTTGAAGTACA), S58A (TTCAAGGGGAGGATGGCGGGCAACTTCACC/GGTGAAGTTGCCCGCCATCCTCCCCTTGAA), G59A (GGGGAGGATGTCGGCCAACTTCACCGAGAAAC/GTTTCTCGGTGAAGTTGGCCGACATCCTCCCC), N60A (GGGAGGATGTCGGGCGCCTTCACCGAGAAACACTTT/AAAGTGTTTCTCGGTGAAGGCGCCCGACATCCTCCC), F61A (GAGGATGTCGGGCAACGCCACCGAGAAACACTTTGTG/CACAAAGTGTTTCTCGGTGGCGTTGCCCGACATCCTC), T62A (GATGTCGGGCAACTTCGCCGAGAAACACTTTGTG/CACAAAGTGTTTCTCGGCGAAGTTGCCCGACATC), E63A (CGGGCAACTTCACCGCGAAACACTTTGTGAACGT/ACGTTCACAAAGTGTTTCGCGGTGAAGTTGCCCG), K64A (GGGCAACTTCACCGAGGCACACTTTGTGAACGTGGG/CCCACGTTCACAAAGTGTGCCTCGGTGAAGTTGCCC), and H65A (GGCAACTTCACCGAGAAAGCCTTTGTGAACGTGGGTATC/GATACCCACGTTCACAAAGGCTTTCTCGGTGAAGTTGCC). After mutagenesis, all constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (ABI Prism 3100; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

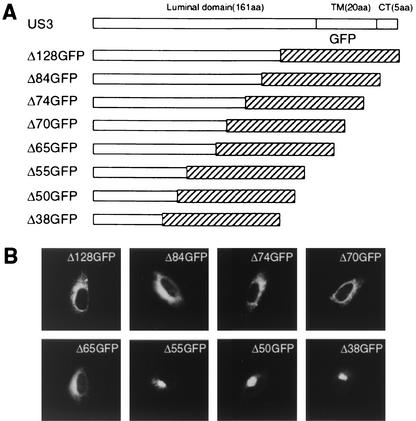

FIG. 1.

Essential domain for ER retention of the US3 glycoprotein. (A) Schematic diagram of the chimeric constructs with the GFP reporter and US3 luminal domain used to identify the retention elements. TM, transmembrane domain; CT, cytoplasmic tail. (B) HtTa cells expressing the indicated mutants were analyzed for intracellular localization by immunofluorescence microscopy. Similar results were obtained in at least three independent experiments.

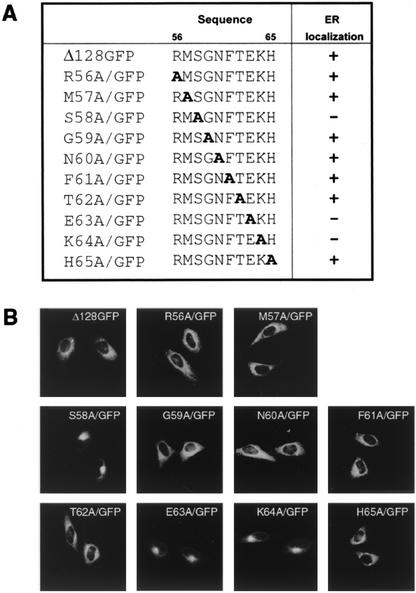

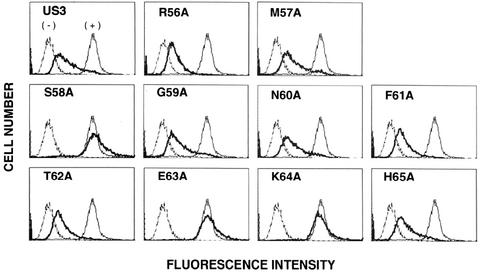

FIG. 2.

Specific sequence requirement of Δ128/GFP on ER retention. (A) Amino acid sequence of native US3 and of mutations in luminal domain region 56 to 65. A systemic series of 10 alanine replacement mutations were introduced into the region 56 to 65 of Δ128/GFP. The mutated residues are in boldface. To the right, the cellular distributions of the chimeras are summarized. (B) HtTa cells transiently expressing the indicated mutants were analyzed for intracellular localization by immunofluorescence microscopy.

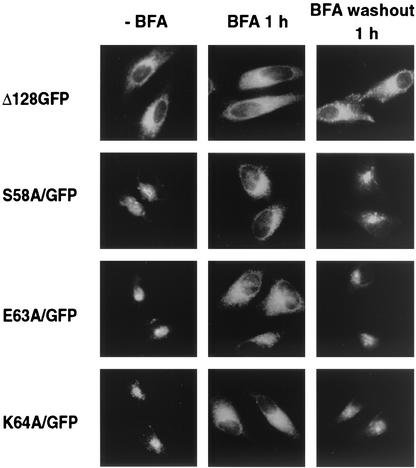

FIG. 3.

Effect of BFA on the Golgi localization of three point mutants. HtTa cells expressing the indicated mutants were incubated in the presence of BFA (5 μg/ml) for 1 h (middle column). After BFA was removed from the medium, cells were incubated for 1 h (right column). Expression of mutants was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy.

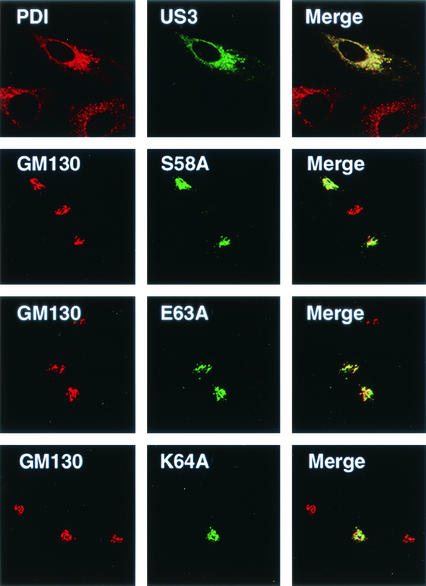

FIG. 4.

Essential role of three amino acid residues for ER retention in the context of homologous US3. Alanine replacement mutations were directly introduced into the region 56 to 65 of homologous US3, as was done for Δ128/GFP. Colocalization of the US3 mutants with marker proteins was analyzed by confocal laser microscopy. HtTa cells stably expressing wild-type US3 or S58A, E63A, or K64A mutants were fixed, permeabilized, and double immunostained with anti-US3 for each mutant (middle column) and with anti-PDI or anti-GM130 antibody for endogenous marker proteins (left column). The right column shows merged images.

FIG. 6.

Effect of disruption of the ER retention signal on the cell surface expression of MHC class I molecules. The surface levels of MHC class I molecules in cells expressing US3 point mutants were measured by flow cytometry with MAb W6/32. Thin lines represent the staining of mock-transfected cells without (−) or with (+) primary antibody in the presence of FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. Bold lines represent the staining of mutant-expressing cells.

Transfections, stable cell lines, and drug treatments.

HeLa cells containing the tetracycline-inducible transactivator (HtTa cells) (11) were transfected by the calcium phosphate method as described previously (3). For transient experiments, HtTa cells were incubated with the transfection solution for 16 h and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Transfectants were analyzed 48 h after partial induction in the presence of 0.1 μM tetracycline as described previously (3). To establish stable cell lines that expressed each point mutant, each mutant plasmid construct was cotransfected with a plasmid conferring ouabain resistance (2). Stable clones were selected by adding ouabain (1 μM) for 24 h each week. Brefeldin A (BFA) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 5 mg/ml for use as a 1:1,000 dilution. The protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) was prepared as a 2-mg/ml stock solution and used as a 1:1,000 dilution.

Antibodies.

The K455 antibody recognizes the MHC class I heavy chain (HC) and β2-microglobulin (β2m) in both assembled and nonassembled forms (4). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) W6/32 recognizes only the complex of HC and β2m. Polyclonal antiserum (anti-US3) for detecting US3 was raised against the synthetic peptides corresponding to the luminal N-terminal portion (residues 16 to 35) of the proteins (1). The MAbs protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (SPA-891) and GM130 were purchased from StressGen (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) and BD Transduction Laboratories (Franklin Lakes, N.J.), respectively. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and Texas red-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, Pa.).

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were methionine starved for 30 min in methionine-free medium prior to pulse-labeling for 30 min with 0.1 mCi of [35S]methionine per ml (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.). The label was chased at the indicated time points with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. After one wash with cold PBS, cells were lysed for 30 min at 4°C with either 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40; Sigma) in PBS or 1% digitonin (Calbiochem) in PBS. The lysates were precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads for 1 h. After incubation with primary antibody, the lysates were incubated with protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). The beads were washed four times with 0.1% NP-40 or 0.1% digitonin, and the immunoprecipitates were eluted by boiling in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Gels were dried, exposed to BAS film, and analyzed by the Phosphor Imaging System BAS-2500 (Fuji Film Company, Japan). For endo-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (endo H) treatment, immunoprecipitates were digested for 16 h at 37°C with 3 mU of endo H (Roche, Penzberg, Germany) in a buffer containing 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.6), 0.3% SDS, and 150 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy.

Expression of MHC class I glycoproteins on the membrane was determined by flow cytometry (FACScalibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) after indirect immunofluorescence with the anti-MHC class I MAb W6/32 and an FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody. HeLa cells expressing autofluorescing GFP-tagged proteins were fixed and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. For immunofluorescence staining of permeabilized cells, HeLa cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, made permeable with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody for 1 h. MRC-1024 confocal microscopy was used for confocal imaging (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

RESULTS

Identifying ER retention sequences in the luminal domain of US3 with the reporter protein GFP.

US3 is a type I transmembrane protein of the ER that does not contain identifiable ER localization signals, such as a double-lysine motif located near the COOH terminus. From previous studies, we know that truncated forms of US3, consisting of luminal portions of US3 that are not anchored to the membrane, are retained in the ER (20). To further define the region responsible for ER retention, we made sequential deletions of amino acids from the COOH terminus of the US3 luminal domain and fused each deletion construct to the NH2 terminus of GFP (Fig. 1A). We chose GFP as the reporter protein for our studies because of its intrinsic fluorescence properties and because of its excellent performance as a reporter protein for subcellular localization studies (10, 26). To minimize the influence of overexpression on subcellular localization, we expressed each chimeric gene in the tetracycline-inducible HtTa cells by transient transfection. After initial experiments indicated that 0.1 μM tetracycline downregulated the levels of protein expression by seven- to eightfold when compared with the expression levels without tetracycline (data not shown), we used this concentration for induction of protein expression throughout the study. The intracellular distribution of the mutant proteins was examined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1B). The constructs with C-terminal deletions between amino acids 128 (Δ128GFP) and 65 (Δ65GFP) were localized in the ER compartment, but the shorter deletion mutants, Δ55GFP, Δ50GFP, and Δ38GFP, all showed a typical Golgi staining pattern. Thus, the sequence motif between amino acids 65 and 56 appeared to be responsible for ER localization.

To further narrow the localization determinant present within residues 56 to 65 of HCMV US3, we substituted different residues by site-directed mutagenesis. For each position, the appropriate codon was altered such that the mutant encoded an alanine residue (Fig. 2A). Fluorescence microscopy analysis of the constructs transiently expressed in HtTa cells showed that three of the replacement mutants, S58A/GFP, E63A/GFP, and K64A/GFP, deviated from the typical ER localization pattern and instead exhibited a juxtanuclear Golgi localization (Fig. 2B). To further ascertain whether these mutants indeed exit from the ER and are distributed in the Golgi, we analyzed the effect of BFA on the intracellular localization of the proteins. BFA prevents forward transport from the ER and relocates Golgi proteins to the ER (25). Upon BFA treatment of transiently transfected cells for 1 h, the distribution of S58A/GFP, E63A/GFP, and K64A/GFP changed from a Golgi to an ER staining pattern (Fig. 3, middle column). When BFA was washed out, these mutants redistributed into a Golgi staining pattern. In contrast, BFA did not affect the distribution of parental Δ128GFP, indicating that unlike the S58A/GFP, E63A/GFP, and K64A/GFP point mutants, Δ128GFP is strictly retained in the ER (Fig. 3). Taken together, these data indicate that the specific sequence of Ser58-Glu63-Lys64 in the luminal domain (termed “S/EK sequence” hereafter) dictates ER retention of the chimeric proteins.

Confirming the S/EK sequence of ER retention in the homologous context of US3.

To analyze whether the S/EK sequence identified by using the described heterologous GFP chimeric system could function similarly in the homologous context of the US3 glycoprotein, we introduced a site-directed point mutation into the corresponding positions of wild-type US3. We established stable cell lines in which each point mutant was expressed independently in HtTa cells and examined the intracellular distribution of the expressed proteins by confocal microscopy. The distribution patterns of full-length US3 point mutants were very similar to the patterns observed for the corresponding Δ128GFP point mutants, as shown in Fig. 2. More precisely, S58A, E63A, and K64A were localized in the cis-Golgi, as evidenced by the colocalization of these mutants with GM130 (Fig. 4), a cis-Golgi marker protein (31); however, the point mutants did not colocalize with PDI, an ER resident marker protein (data not shown). In contrast, the wild-type US3 glycoprotein was detected in the ER, colocalized with PDI, and costained with PDI protein (Fig. 4). The other point mutants (R56A, M57A, G59A, N60A, F61A, T62A, and H65A) also colocalized with PDI, indicative of ER localization (data not shown).

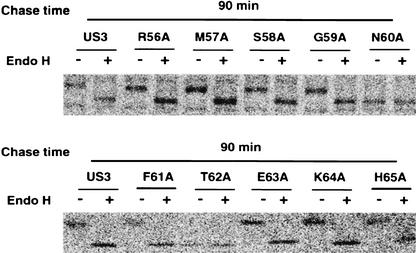

To gain independent evidence of the intracellular distribution of US3 point mutants, we analyzed their endo H sensitivity after pulse-chase labeling. The US3 protein contains an N-glycosylation site at position 60. endo H removes only high-mannose N-linked side chains of proteins that reside in the ER or cis-Golgi, and therefore the appearance of the endo H-resistant forms indicates that proteins were transported to or through the medial-Golgi (38). In agreement with previous studies (20), wild-type US3 was completely sensitive to endo H digestion after a 90-min chase. All US3 point mutants were also sensitive to endo H digestion under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 5). E63A and K64A mutants, which are not supposed to be retained in the ER, are also deglycosylated by endo H, suggesting that they are transported to the cis-Golgi. As expected, N60A and T62A proteins were not glycosylated, because each point mutation disrupted an N-linked glycosylation site. Immunofluorescence results showed the distribution of N60A and T62A in the ER (data not shown), supporting the lack of involvement of carbohydrate moieties in the ER's retention of the US3 glycoprotein. In accordance with the colocalization experiments, our data indicate that the S/EK sequence could also function as an ER retention signal in the context of the wild-type US3 glycoprotein.

FIG. 5.

Effect of single mutations of US3 on ER retention by endo H sensitivity. HtTa cells stably expressing the indicated mutants were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min and chased for 90 min with normal medium. The expressed proteins were immunoprecipitated with the anti-US3 antibody and then were left untreated (−) or were treated (+) with endo H before analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Retention of US3 in the ER is essential to its ability to downregulate the cell surface expression of class I molecules.

To analyze the importance of the US3 S/EK ER-retention sequence for inhibition of surface expression of class I molecules, we examined the cell surface expression of class I molecules in cells stably expressing US3 point mutants. Wild-type US3 downregulated the expression of class I molecules at the cell surface, as previously observed (1). In the same experiment, downregulation of MHC class I molecules was also observed in the cells independently expressing R56A, M57A, G59A, N60A, F61A, T62A, and H65A. In contrast, no detectable change of surface level expression of class I molecules was observed in cells expressing the S58A, E63A, and K64A mutants (Fig. 6), which are no longer retained in the ER (see Fig. 4). These findings indicate that the ability of US3 to inhibit the cell surface expression of class I molecules is due solely to its ability to retain class I molecules in the ER.

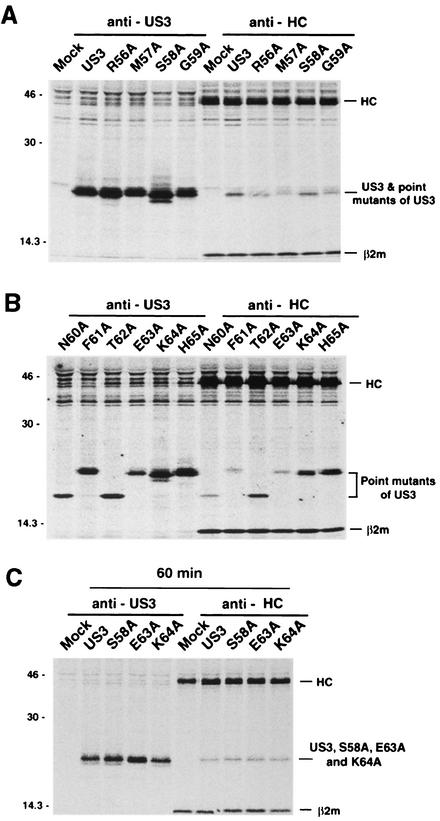

The US3 glycoprotein downregulates surface levels of class I molecules by binding intracellular class I molecules in the ER and preventing them from reaching the plasma membrane. Thus, no discernible downregulation of surface levels of class I molecules that was observed for the S58A, E63A, and K64A point mutants could possibly result from the inability of the mutants to bind class I molecules. To examine this possibility, we characterized the ability of each mutant to bind class I molecules by coimmunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitation of digitonin lysates with anti-class I HC (K455) revealed that similar to wild-type US3, all US3 mutants, including S58A, E63A, and K64A, formed complexes with class I molecules, albeit with some differences in their relative affinities (Fig. 7A and B). As a control, β2m was coprecipitated from both mock- and US3 mutant-transfected cells. These data suggest that the region between residues 56 and 65 (the region containing the ER retention sequence) is not involved in interactions with class I molecules.

FIG. 7.

Association of US3 point mutants with MHC class I molecules. HtTa cells stably expressing the mutants were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min (A and B) and further incubated for 60 min in normal medium with cycloheximide (C). Cells were lysed with 1% digitonin lysis buffer, and the lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-US3 and anti-HC (K455) antibodies.

Biochemical, immunolocalization, and fluorescence-activated cell sorter data indicate that S58A, E63A, and K64A localize in the cis-Golgi, and class I molecules from cells expressing these mutants eventually reach the cell surface. Since these mutants maintain their ability to bind class I molecules over the 30-min pulse (Fig. 7A and B), we investigated whether class I molecules and US3 exist as complexes in the cis-Golgi. Cells independently expressing these mutants were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min. During the 60-min chase, the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide was added. After 60 min of incubation, the majority of US3 mutants colocalized with class I molecules in the cis-Golgi (data not shown). In the same experiment, a possible association between the mutant and class I molecules was assessed by coimmunoprecipitation. Using the anti-HC antibody (K455), coprecipitation with class I molecules was observed for all of the mutants (Fig. 7C), indicating that at least they associated with each other in the cis-Golgi compartment. On the basis of these findings, we predict that these US3 point mutants accompany class I molecules to the cis-Golgi and are retained in the cis-Golgi, whereas class I molecules dissociated from US3 mutants are transported to the cell surface.

DISCUSSION

MHC class I molecules are retained in the ER in cells expressing the US3 protein of HCMV (1, 19). The US3 protein is an ER resident and forms a ternary complex with HC-β2m. The structure of the US3 protein that causes ER retention has been localized to the 146 amino acids at the NH2 terminus of the protein and protrudes from the luminal side of the ER membrane (1). In this study, we have examined the luminal domain of the US3 protein in detail, with the aim of identifying which amino acids are crucial for retention. Mutagenesis of the luminal sequence of US3 indicates that the RMSGNFTEKH sequence, more specifically, Ser58, Glu63, and Lys64 residues (underlined), is required for retention. Mutations in which an alanine residue is substituted for any of these three amino acids cause loss of retention. Interestingly, these US3 mutants maintain their ability to bind class I molecules; however, the mutants are unable to retain class I molecules in the ER and unable to block the cell surface expression of class I molecules. These findings indicate that the properties that allow US3 to be localized in the ER and bind class I molecules are located in different parts of the molecule and that the ability of US3 to block antigen presentation is due solely to its ability to retain class I molecules in the ER.

In general, the retention signals of resident ER membrane proteins have been mapped within the transmembrane domain or cytoplasmic tail (9, 34, 39). In some cases, the transmembrane domain cooperates with the cytosolic or luminal domains to specify ER localization (16, 22, 37). The S/EK motif of the US3 glycoprotein is unique in that it is present in the luminal domain of an intrinsic membrane protein. Neither the transmembrane nor cytoplasmic domain is necessary for retention of US3 in the ER (20). Thus, the putative receptor that recognizes the S/EK sequence is likely located within the lumen of the ER, whereas the receptor for KKXX and related sequences is located on the cytoplasmic side of the ER. To date, this is the first example of an ER localization motif of a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that has been mapped to the luminal domain, although it remains to be further investigated whether this motif might function as an ER retention signal in the context of other proteins. The other transmembrane protein with an ER localization motif in the luminal domain is the yeast Sec20 protein (6, 36), a type II transmembrane protein with a C-terminal HDEL sequence that serves as a retention signal (39).

Evidence for the existence of a variety of different ER retention mechanisms comes from the ongoing discovery of soluble ER resident proteins that lack any identifiable retrieval signal. For example, the amino acid sequence VEKPFAIAKE has been identified in s-cyclophilin and is involved in its localization to a subcompartment of the ER (5). PDI and related proteins form a complex superfamily. In most cases studied, they behave as classical ER resident enzymes. This steady-state distribution of PDI is the result of a combination of direct retention and retrieval of ER escapees (8, 28). Even though most of the PDI proteins present in the database bear at their COOH termini a classical ER retrieval signal in the form of a KDEL-type motif (Table 1), some proteins, including PDI of Dictyostelium discoideum, do not follow this rule. Therefore, a general mechanism of ER retention for such proteins must exist. In fact, one recent study indicates that the C-terminal 57 amino acids are sufficient to localize D. discoideum PDI to the ER (29). It is interesting to note that the EK amino acid sequence in these 57 amino acids is conserved among PDI members, which lack a KDEL-type motif. This sequence is also found in VEKPFAIAKE and RMSGNFTEKH, the ER localization motifs of s-cyclophilin and US3, respectively (underlined). At present, we do not know whether the EK residues in these sequences represent another type of novel ER retention motif that is identifiable in the luminal domain of ER resident proteins. Because serine at position 58, in addition to the EK motif, is critical for ER retention of US3, the mechanism for the ER retention of US3 might be more complex.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of luminal ER retention signals and sequence alignment of PDI-D homologuesa

| Protein | Sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| HCMV US3 | RMSGNFTEKH | This study |

| s-Cyclophilin | VEKPFAIAKE | 5 |

| D. discoideum PDI | EGSYYVKVMKTIAEKSIDFVTTEIARITKLVSGSMSGKKADEFAKKLNILESFKSK | 29 |

| D. discoideum PDI | EGSYYVKVMKTIAEKSIDFVTTEIARITKLVSGSMSGKKADEFAKKLNILESFKSK | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana PDI | YGKLYLKLAKSYIEKGSDYASKETERLGRVLGKSISPVKADELTLKRNILTTFVASS | |

| Nicotiana tabacum PDI | YGKIYLKAAKSSMEKGADYAKNEIQRLERMLAKSISPAKSDEFTLKKNILATFA | |

| Medicago sativa PDI | YGKIYLKVSKKYLEKGSDYAKNEIQRLERLLEKSISPAKADELTLKKNILSTYA | |

| Rattus norvegicus ERp29 | WASQYLKIMGKILDQGEDFPASELARISKLIENKMSEGKKEELQRSLNILTAFRKKGAEKEEL | |

| Homo sapiens ERp28 | WAEQYLKIMGKILDQGEHFPASEMTRIARLIEKNKMSDGKKEELQKSLNILTAFQKKGAEKEEL | |

| Drosophila melanogaster Windbeutel | NARAYLIYMRKIHEVGYDFLEEETKRLLRLKAGKVTEAKKEELLRKLNILEVFRVHKVTKTAPEKEEL |

The ER retention signals of US3 are compared with those of other proteins. The underlines indicate that the sequence is required for ER localization of US3, while predicted ER retention sequences are in italics. The KDEL-like retrieval signal is in boldface. The sources and accession numbers of protein sequences are by organism as follows. D. discoideum, AAB86685; A. thaliana, NP_182269; N. tabacum, T03644; M. sativa, P38661; R. norvegicus, NP_446413; Homo sapiens, NP_006808; and D. melanogaster, AAC02944.

Currently, we can only speculate by which molecular mechanism the S/EK motif mediates the ER retention of US3. Retention by the S/EK motif might depend on the existence of a putative S/EK receptor, itself an ER resident protein, as is the case for KDEL proteins (27). The sequence requirements in the luminal domain suggest that a relatively specific interaction of the S/EK motif with lipids or other proteins is involved. Intriguingly, when wild-type US3 was overexpressed in the absence of tetracycline, we observed that wild-type US3 exited the ER in a minor proportion: 3 to 5% of transfected cells (data not shown). Gruhler et al. (12) also observed that a fraction of the US3 proteins expressed under the CMV promoter traffic to the Golgi and are degraded in lysosomes. We thus predict that the US3 mutants that are apparently retained within the cis-Golgi might be transported to the lysosomes by default and are in turn subjected to degradation. This observation does not necessarily conflict with the other findings we present here, but rather, it supports the concept that the retention machinery mediated by the S/EK motif is saturable, a phenomenon that was also reported for the KDEL-bearing ER protein BiP (32). It is, on the other hand, unlikely that the sequence RMSGNFTEKH of US3 exclusively functions as a KDEL substitute, because of the well-documented specific requirements of this retention motif (32) and because US3 is not retrieved from the Golgi (20). The S/EK motif might mediate direct interaction with the lipid head groups of the membrane or might be involved in the interaction of membrane proteins with each other to form oligomeric complexes or even larger assemblies such that the US3 protein is unable to enter transport vesicles. Alternatively, US3 proteins might be retained in the ER indirectly by interaction with ER resident proteins or by quality control mechanisms. Because the bulk of the US3 protein is on the luminal side of the ER membrane, US3 has every opportunity to interact with these ER resident proteins. For example, luminal chaperones, including BiP, calnexin, and calreticulin, interact with newly synthesized proteins in the ER lumen and mediate transient or stable retention of proteins that are devoid of intrinsic ER retention and retrieval sequences (13). However, because our data demonstrated that deglycosylated US3 proteins are retained in the ER (Fig. 5), we exclude the possibility that US3 is retained in the ER by a quality control mechanism that is mediated by calnexin or calreticulin in which it associates with glucosylated N-glycans (14). Our finding of novel ER retention sequence for the type I transmembrane protein should offer the unique opportunity to investigate nonclassical mechanisms for retrieval and retention of abundant ER proteins at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Edmunds for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Research Foundation (R01-1999-00143) and in part by a Korea University grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, K., A. Angulo, P. Ghazal, P. A. Peterson, Y. Yang, and K. Fruh. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits antigen presentation by a sequential multistep process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10990-10995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, K., A. Gruhler, B. Galocha, T. R. Jones, E. J. Wiertz, H. L. Ploegh, P. A. Peterson, Y. Yang, and K. Fruh. 1997. The ER-luminal domain of the HCMV glycoprotein US6 inhibits peptide translocation by TAP. Immunity 6:613-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, K., T. H. Meyer, S. Uebel, P. Sempe, H. Djaballah, Y. Yang, P. A. Peterson, K. Fruh, and R. Tampe. 1996. Molecular mechanism and species specificity of TAP inhibition by herpes simplex virus ICP47. EMBO J. 15:3247-3255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson, M., S. Paabo, T. Nilsson, and P. A. Peterson. 1985. Impaired intracellular transport of class I MHC antigens as a possible means for adenoviruses to evade immune surveillance. Cell 43:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arber, S., K. H. Krause, and P. Caroni. 1992. s-Cyclophilin is retained intracellularly via a unique COOH-terminal sequence and colocalizes with the calcium storage protein calreticulin. J. Cell Biol. 116:113-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cosson, P., S. Schroder-Kohne, D. S. Sweet, C. Demolliere, S. Hennecke, G. Frigerio, and F. Letourneur. 1997. The Sec20/Tip20p complex is involved in ER retrieval of dilysine-tagged proteins. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 73:93-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty, P. C., W. Allan, M. Eichelberger, and S. R. Carding. 1992. Roles of alpha beta and gamma delta T cell subsets in viral immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 10:123-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorner, A. J., L. C. Wasley, P. Raney, S. Haugejorden, M. Green, and R. J. Kaufman. 1990. The stress response in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Regulation of ERp72 and protein disulfide isomerase expression and secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 265:22029-22034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duvet, S., L. Cocquerel, A. Pillez, R. Cacan, A. Verbert, D. Moradpour, C. Wychowski, and J. Dubuisson. 1998. Hepatitis C virus glycoprotein complex localization in the endoplasmic reticulum involves a determinant for retention and not retrieval. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32088-32095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girotti, M., and G. Banting. 1996. TGN38-green fluorescent protein hybrid proteins expressed in stably transfected eukaryotic cells provide a tool for the real-time, in vivo study of membrane traffic pathways and suggest a possible role for ratTGN38. J. Cell Sci. 109:2915-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gossen, M., and H. Bujard. 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5547-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruhler, A., P. A. Peterson, and K. Fruh. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early glycoprotein US3 retains MHC class I molecules by transient association. Traffic 1:318-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond, C., and A. Helenius. 1995. Quality control in the secretory pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7:523-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helenius, A. 1994. How N-linked oligosaccharides affect glycoprotein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 5:253-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi, R., B. Krummel, and R. K. Saiki. 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:7351-7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobman, T. C., H. F. Lemon, and K. Jewell. 1997. Characterization of an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal in the rubella virus E1 glycoprotein. J. Virol. 71:7670-7680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itin, C., R. Schindler, and H. P. Hauri. 1995. Targeting of protein ERGIC-53 to the ER/ERGIC/cis-Golgi recycling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 131:57-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson, M. R., T. Nilsson, and P. A. Peterson. 1993. Retrieval of transmembrane proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 121:317-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, T. R., E. J. Wiertz, L. Sun, K. N. Fish, J. A. Nelson, and H. L. Ploegh. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus US3 impairs transport and maturation of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11327-11333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S., J. Yoon, B. Park, Y. Jun, M. Jin, H. C. Sung, I.-H. Kim, S. Kang, E.-J. Choi, B. Y. Ahn, and K. Ahn. 2000. Structural and functional dissection of human cytomegalovirus US3 in binding major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. J. Virol. 74:11262-11269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letourneur, F., E. C. Gaynor, S. Hennecke, C. Demolliere, R. Duden, S. D. Emr, H. Riezman, and P. Cosson. 1994. Coatomer is essential for retrieval of dilysine-tagged proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 79:1199-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Letourneur, F., S. Hennecke, C. Demolliere, and P. Cosson. 1995. Steric masking of a dilysine endoplasmic reticulum retention motif during assembly of the human high affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E. J. Cell Biol. 129:971-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis, M. J., and H. R. Pelham. 1990. A human homologue of the yeast HDEL receptor. Nature 348:162-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis, M. J., and H. R. Pelham. 1992. Ligand-induced redistribution of a human KDEL receptor from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 68:353-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippincott-Schwartz, J., L. C. Yuan, J. S. Bonifacino, and R. D. Klausner. 1989. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 56:801-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, J., T. E. Hughes, and W. C. Sessa. 1997. The first 35 amino acids and fatty acylation sites determine the molecular targeting of endothelial nitric oxide synthase into the Golgi region of cells: a green fluorescent protein study. J. Cell Biol. 137:1525-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Locker, J. K., D. J. Opstelten, M. Ericsson, M. C. Horzinek, and P. J. Rottier. 1995. Oligomerization of a trans-Golgi/trans-Golgi network retained protein occurs in the Golgi complex and may be part of its retention. J. Biol. Chem. 270:8815-8821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzarella, R. A., M. Srinivasan, S. M. Haugejorden, and M. Green. 1990. ERp72, an abundant luminal endoplasmic reticulum protein, contains three copies of the active site sequences of protein disulfide isomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 265:1094-1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monnat, J., E. M. Neuhaus, M. S. Pop, D. M. Ferrari, B. Kramer, and T. Soldati. 2000. Identification of a novel saturable endoplasmic reticulum localization mechanism mediated by the C-terminus of a Dictyostelium protein disulfide isomerase. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3469-3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munro, S., and H. R. Pelham. 1987. A C-terminal signal prevents secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell 48:899-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, N., C. Rabouille, R. Watson, T. Nilsson, N. Hui, P. Slusarewicz, T. E. Kreis, and G. Warren. 1995. Characterization of a cis-Golgi matrix protein, GM130. J. Cell Biol. 131:1715-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelham, H. R. 1989. Control of protein exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 5:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinaldo, C. R., Jr. 1990. Immune suppression by herpesviruses. Annu. Rev. Med. 41:331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothman, J. E., and F. T. Wieland. 1996. Protein sorting by transport vesicles. Science 272:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schutze, M. P., P. A. Peterson, and M. R. Jackson. 1994. An N-terminal double-arginine motif maintains type II membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 13:1696-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sweet, D. J., and H. R. Pelham. 1992. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SEC20 gene encodes a membrane glycoprotein which is sorted by the HDEL retrieval system. EMBO J. 11:423-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szczesna-Skorupa, E., K. Ahn, C. D. Chen, B. Doray, and B. Kemper. 1995. The cytoplasmic and N-terminal transmembrane domains of cytochrome P450 contain independent signals for retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24327-24333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarentino, A. L., and F. Maley. 1974. Purification and properties of an endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Streptomyces griseus. J. Biol. Chem. 249:811-817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teasdale, R. D., and M. R. Jackson. 1996. Signal-mediated sorting of membrane proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:27-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]