Abstract

We studied the cholinergic modulation of glutamatergic transmission between neighboring layer 5 regular-spiking pyramidal neurons in somatosensory cortical slices from young rats (P10-P26). Brief bath application of 5-10 μM carbachol, a nonspecific cholinergic agonist, decreased the amplitude of evoked unitary excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs). This effect was blocked by 1 μM atropine, a muscarinic receptor antagonist. Nicotine (10 μM), in contrast to carbachol, reduced EPSPs in nominally magnesium-free solution but not in the presence of 1 mM Mg+2, indicating the involvement of NMDA receptors. Likewise, when the postsynaptic cell was depolarized under voltage clamp to allow NMDA receptor activation in the presence of 1 mM Mg+2, synaptic currents were reduced by nicotine. Nicotinic EPSP reduction was prevented by the NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (50 μM) and by the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine (10 μM). Both carbachol and nicotine reduced short-term depression of EPSPs evoked by 10 Hz stimulation, indicating that EPSP reduction happens via reduction of presynaptic glutamate release. In the case of nicotine, several possible mechanisms for NMDAR-dependent EPSP reduction are discussed. As a result of NMDA receptor dependence, nicotinic EPSP reduction may serve to reduce the local spread of cortical excitation during heightened sensory activity.

Keywords: acetylcholine, pyramidal neuron, NMDA receptor, synaptic plasticity

Introduction:

Cholinergic input from the basal forebrain influences cortical functions such as learning, memory, and attention (Descarries et al., 2004) through the activity of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Much of the effect of acetylcholine (ACh) may arise from modulation of excitatory (glutamatergic) synaptic transmission (Hasselmo and Bower, 1992; Vidal and Changeux, 1993; Gil et al., 1997; Aramakis and Metherate, 1998) and consequent ‘gating’ of sensory information during arousal (Steriade et al., 2001).

Past in vitro studies have used whole-cell recording in conjunction with extracellular stimulation in slice preparations to examine cholinergic modulation of cortical excitatory pathways. The general consensus among these studies is that ACh enhances glutamate release at thalamo-cortical synapses via nicotinic receptors while reducing glutamate release at cortico-cortical synapses via muscarinic receptors, at least within superficial, presumably thalamo-recipient layers 2-4 (Hasselmo and Bower, 1992; Vidal and Changeux, 1993; Gil et al., 1997; Hsieh et al., 2000). Acetylcholine’s selective enhancement of sensory responses relative to cortico-cortical responses has been corroborated in vivo using natural stimuli (Oldford and Castro-Alamancos, 2003).

In addition to synaptic effects, ACh and cholinergic agonists change the excitability and firing properties of cortical pyramidal neurons, primarily through the activity of muscarinic receptors (Krnjevic et al., 1971; McCormick, 1992). Moreover, ACh acts on inhibitory neurons as well, both through synaptic effects on GABA release (Metherate and Ashe, 1995) and through effects on cell excitability (McCormick and Prince, 1986; Christophe et al., 2002) that may vary among different inhibitory neuronal classes (Kawaguchi, 1997; Xiang et al., 1998; Porter et al., 1999).

The pathway specific findings summarized above are drawn largely from examination of thalamo-cortical or relatively long-range cortico-cortical connections terminating in thalamo-recipient layers (but see Kimura et al., 1999). Extracellular stimulation methods have prevented examination of the local connections (within a few hundred microns) that are prevalent throughout cortex, and little is known in particular about the cholinergic modulation of excitatory connections in the deeper layers. Neighboring layer 5 pyramidal neurons in young rat somatosensory cortex are synaptically connected with a frequency of at least 10%, and about a third of these connections are bidirectional (Markram et al., 1997; compare Thomson et al., 1993; Deuchars et al., 1994). Recurrent excitation among neighboring excitatory neurons may amplify and sharpen sensory input, or it may alter sensory receptive field properties in other ways, depending on the exact connectivity (Ben-Yishai et al., 1995; Douglas et al., 1995; Chance et al., 1999; reviewed in Sompolinsky and Shapley, 1997). Application of cholinergic agonists or antagonists, or manipulation of endogenous cholinergic pathways, has been shown to change the receptive field properties of somatosensory (Metherate et al., 1988) and auditory cortical neurons (Ashe et al., 1989; McKenna et al., 1989) in vivo. We speculated that modulation of local excitatory synaptic transmission by ACh might contribute to these changes. Here we used dual intracellular recording to examine unitary EPSPs evoked between pairs of layer 5 pyramidal neurons. This approach has allowed us to analyze the effects of ACh on a specific intra-cortical circuit that has not been accessible to previous studies using extracellular stimulation.

Experimental Procedures:

Slice preparation and recording:

Details of the slice preparation and recording were as described previously (Reyes and Sakmann, 1999; Chance et al., 2002), and conformed to protocols approved by the New York University Animal Welfare Committee. Wistar rats (postnatal day 10-26) were decapitated after anaesthesia via halothane inhalation, and 300 μm parasagittal slices containing somatosensory cortex were made using a vibrating microtome (Leica Instruments GmbH, Nussloch, Germany). Slices were placed in the recording chamber and perfused with oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF: 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 32-34 °C (flow rate 1-2 mL/min). In some experiments, standard ACSF was replaced by magnesium-free ACSF (0 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, otherwise as described above) to unmask the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR). Inclusion of 40 μM glycine (NMDAR cofactor) in some experiments did not affect evoked EPSPs appreciably.

Slices were viewed under infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy (Stuart et al., 1993). Layer 5 pyramidal cells were identified by their large somata and prominent apical dendrites. The somata of the recorded cells were always less than 350 μm apart, and usually less than 100 μm apart. Whole-cell recordings were made from up to four cells simultaneously, using pipettes with 8-12 MOhm resistance when filled with 100 mM K-gluconate, 20 mM KCl, 4 mM ATP-Mg, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 0.3 mM GTP, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.3. Recordings were made using BVC-700A amplifiers (Dagan corp., Minneapolis, MN), digitized at 10 kHz using an ITC-18 interface (Instrutech corp., Port Washington, NY), and stored on a computer using Igor software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Voltages were corrected for liquid junction potential using the offset control on the amplifier. Input resistance was measured on initial break-in by measuring the voltage response to 1 s incremental current steps.

For voltage clamp recording, the intracellular solution for the postsynaptic cell was as described above, except that Cs-gluconate was substituted for K-gluconate, and 5 mM QX-314 (Tocris Cookson, Ellisville, MO) was included to block voltage-dependent Na channels.

In synaptically connected cells, suprathreshold stimulation evoked unitary EPSPs in the target cell(s). Connections were monosynaptic as evidenced by short average latency, monophasic rising component, and small average amplitude (see results). Presynaptic cells were stimulated with a series of 1 to 10 pulses, each of 5 ms duration, at 10 Hz (3 pulses were used in most experiments). Unitary evoked EPSPs were monitored continuously at approximately 10 s intervals until peak EPSP amplitudes reached steady-state levels (always within 15 min and usually within ~5 min). During data collection, stimulus trains were separated by at least 6 s to ensure that the system returned to baseline conditions. The interval between stimulus trains was held constant throughout each period of data collection. After data collection, whole-cell recording was re-established with pipettes containing 0.5% biocytin for >20 min; slices were fixed immediately and the filled neurons were later visualized using avidin-biotin and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine / horseradish peroxidase histochemistry (DAB/HRP; Horikawa and Armstrong, 1988), for confirmation of cell type and location.

Drug application:

The following compounds were used: D-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (D-AP5), atropine sulfate, carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol), 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3(1H,4H)-dione (DNQX), mecamylamine hydrochloride, (-)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), tetrodotoxin with citrate buffer (TTX) (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich), AF-DX 116, PD 102807, and pirenzepine dihydrochloride (all purchased from Tocris). For bath application, drugs were prepared as concentrated stock solutions in 0.1 M NaOH (DNQX), 0.1 M HCl (atropine), DMSO (AF-DX 116, PD 102807), or water (all others) and diluted in oxygenated ACSF immediately before use. The final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.1% in solutions containing AF-DX 116 and PD 102807. Bath-applied antagonists were superfused for at least 20 min (atropine) or for at least 10 min (all others), before starting to collect data. For reversible antagonists (D-AP5, mecamylamine, pirenzepine), the order of trials (ACh agonist alone versus ACh agonist plus antagonist) was reversed in successive experiments to negate possible confounding effects of synaptic run-down or receptor desensitization.

For NMDA pressure ejection, data were collected in standard ACSF (1 mM Mg+2/2 mM Ca+2) containing 0.5 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 10 μM DNQX. NMDA-containing pipettes (1-5 MOhm resistance) were positioned 5-20 μm from the apical dendrite, within 50 μm of the soma. NMDA was dissolved in ACSF (pH 8). Pulses of 2-4 ms duration at 20 PSI were delivered using a picospritzer (General Valve, Fairfield, NJ) at 10 s intervals. Current responses were recorded in whole-cell configuration as described above, with the soma held in voltage-clamp mode at -60 mV. Responses were digitized at 1 kHz. Average voltage responses were compiled from >20 sweeps.

Data analysis:

Individual and average (50-100 sweeps) EPSP traces were analyzed off-line using macros written with Igor software. Experiments where the resting membrane potential (Vm) of either a pre- or postsynaptic cell exceeded -50 mV (where persistent spontaneous firing was observed), or where the access resistance increased substantially (>30%) during the course of the experiment, were excluded from the analysis. Over a given set of trials, resting membrane potential generally did not fluctuate by >2 mV. Injection of holding current in some experiments to hold Vm fixed did not affect the data appreciably. Determinations of peak EPSP amplitude, coefficient of variation (CV) and background noise followed Feldmeyer et al. (1999), except as noted. Mean baseline noise was 0.07 +/- 0.02 mV in 1 mM Mg+2 and 0.13 +/- 0.05 mV in 0 mM Mg+2. Connections where the first EPSP in an evoked train had an average amplitude of <0.2 mV were excluded due to poor signal:noise ratio (except for data given under “general properties” in the Results, where only connections <0.1 mV were excluded). EPSP traces that contained spontaneous action potentials or large non-evoked EPSPs (>10x mean evoked EPSP amplitude) were excluded. These typically constituted less than 1% of the data set. For average EPSP traces, individual traces were aligned by triggering to stimulus onset. Triggering to action potential onset (in a subset of the data) yielded results that did not differ appreciably from stimulus-triggered averages. For drug application, a “before” (control) average EPSP was taken from 100 trials immediately preceding drug application; a “during” average was made over the period of peak drug effect (if the effect was unambiguous, e.g. figure 1A) or else from 50 trials beginning 3 min after drug application (if the effect was absent or ambiguous); an “after” average was taken from 50 trials at the end of the washout period. Mean values are presented +/- standard deviation. p-values for statistical significance were obtained from two-tailed, paired t-tests except as noted.

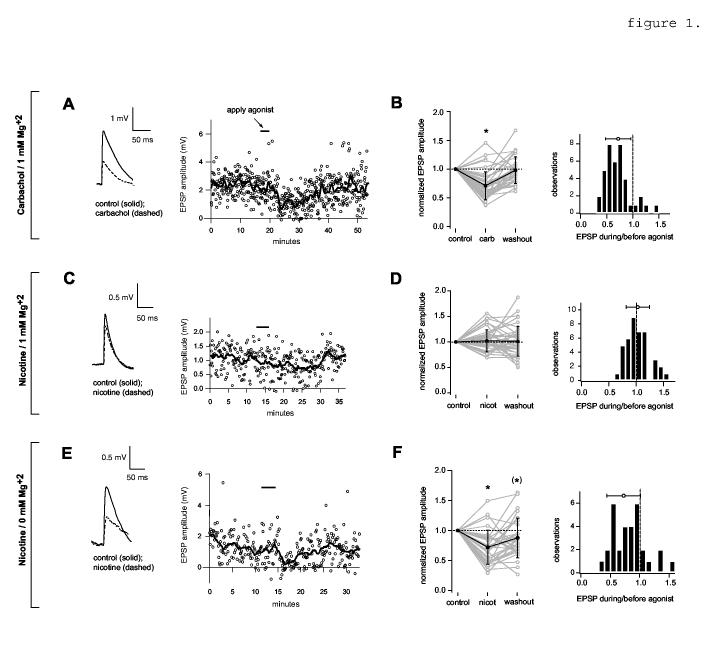

1.

Reduction of evoked unitary EPSPs. A,B, effect of carbachol in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF. A, Left, the solid trace is an EPSP amplitude average compiled from 100 sweeps immediately preceding carbachol application; the dashed trace is the average of 50 sweeps (approximately 6 min) during the period of greatest EPSP suppression following the start of carbachol application (5 μM). Resting Vm = -66 mV; baselines are aligned for comparison. Right, time course of the carbachol-mediated effect on the amplitude of unitary EPSPs. Carbachol was applied for 3 min (bar). Open circles denote the peak amplitudes of unitary EPSPs; the solid line is a sliding boxcar average of the same data (width = 19 data points). B, data for all pairs. Left, average amplitudes before (control) and during agonist application, and after washout. Data are normalized to control values. Grey lines and open circles show values for individual pairs. Black lines and filled circles with error bars show mean and S.D.; values are 0.71 +/- 0.24 (carbachol) and 0.98 +/- 0.23 (washout). The asterisk denotes significance of average agonist value relative to the control (p<0.0001, n=39) and washout values (p<0.0001, n=36; washout data were not obtained for three pairs). Right, histograms showing EPSP amplitude reduction by carbachol. The open circle with bars shows the mean +/- S.D. C,D, Effect of nicotine on evoked unitary EPSP amplitude in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF. C, Left, evoked EPSPs before (control) and during bath application of nicotine (10 μM, 3 min). Resting Vm = -62 mV. Right, time course of EPSP amplitude (open circles) and sliding average. D, data for all pairs. The normalized EPSP amplitude during nicotine is 1.02 +/- 0.22 and the washout value is 1.01 +/- 0.29 (n=41). E, effect of 10 μM nicotine on the same pair as in B, in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF. Resting Vm = -61 mV. (Note: the broadening of the EPSP during nicotine in this trace was not typical; compare traces in figures 3A, 4B, and values in Table 1). F, data for all pairs. The normalized EPSP amplitude during nicotine is 0.72 +/- 0.28 (n=31) and the washout value is 0.85 +/- 0.36 (n=30). The asterisk denotes significance relative to the control (p< 0.0001; n=31) and washout values (p< 0.05; n=30). The bracketed asterisk denotes a significant difference between the control and washout values (p< 0.05, n=30).

Results

General properties.

245 local synaptic connections were found in 3131 unidirectional tests (7.8% connected). Evoked unitary EPSPs were abolished by bath application of 10 μM DNQX (AMPAR antagonist) in conjunction with 50 μM D-AP5 (NMDAR antagonist), indicating that the connections were glutamatergic. Very weak connections (<0.1 mV mean peak amplitude) were not subjected to further data collection. In the remainder of connected pairs, evoked EPSPs had a mean peak amplitude of 0.89 +/- 0.74 mV. Mean latency was 1.6 +/- 1.1 ms, measured from action potential peak to EPSP onset time. Approximately 75% of connected pairs displayed short-term synaptic depression in response to 10 Hz presynaptic stimulation (c.f. Thomson et al., 1993). Upon recovery and light-microscopic examination of representative fixed biocytin-filled pairs, cells were found to be of the thick tufted pyramidal type (Markram et al., 1997) with apical dendritic branches extending into layer 1 (n= 11 intact pairs and 28 total cells).

Reduction of unitary EPSPs by carbachol.

To examine possible modulatory actions of ACh, we first applied the non-hydrolyzable ACh analogue carbachol, which is an agonist for both nicotinic and muscarinic receptors (Brown and Taylor, 1996) but was found to produce mainly muscarinic effects in many in vitro reports (e.g. Auerbach and Segal, 1996; Fernandez de Sevilla et al., 2002). 5-10 μM carbachol, bath-applied for 2-3 min, did not cause significant or reproducible changes in the resting membrane potential or mean input resistance (table 1). This application time and concentration range were used throughout the present study. Longer application times and higher concentrations (20-50 μM) were avoided because they caused substantial depolarization and spontaneous firing (c.f. McCormick, 1992).

Table 1:

Summary of results.

| Carbachol / 1 mM Mg+2 | Nicotine / 1 mM Mg+2 | Nicotine / 0 mM Mg+2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting Vm: | 0.99 ± 0.02 (30) | N.A. | 1.00 ± 0.02 (16) |

| Input resistance: | 1.06 ± 0.11 (11) | N.A. | 1.04 ± 0.14 (19) |

| EPSP1 amplitude: | * 0.71 ± 0.24 (39) | 1.02 ± 0.22 (41) | * 0.72 ± 0.28 (30) |

| EPSP1 width at 0.5×max. amplitude: | 1.07 ± 0.24 (37) | 1.03 ± 0.18 (14) | * 0.86 ± 0.26 (29) |

| EPSP2/EPSP1: | * 1.23 ± 0.28 (39) | 1.04 ± 0.20 (41) | * 1.26 ± 0.43 (29) |

Values are mean and S.D., normalized to control (no agonist). Number of observations (cells or cell pairs) is shown in parentheses. Asterisk denotes significance (p<0.05). N.A. = not analyzed.

Carbachol caused a decrease in peak unitary EPSP amplitude in 34/39 pairs (figure 1A,B). The decrease was reversible upon washout in 31 pairs, and was statistically significant when evaluated for all connected pairs (figure 1B, left panel). The width of the EPSP (measured at one-half peak amplitude) did not change significantly (table 1). The onset of the effect followed drug application after a delay of about 3 min. This was similar to the time course for the onset of EPSP reduction by bath-applied 10 μM DNQX (not shown), indicating that it probably corresponded to the amount of time required for the drug to reach an effective concentration in the recording chamber. EPSP amplitude returned to baseline values within 20 min of the commencement of drug washout (figure 1A, right). The extent of EPSP reduction by carbachol was not appreciably correlated with age (r= 0.05, n= 39) of the animal, with EPSP amplitude measured under control conditions (r= -0.24, n= 39), or with paired-pulse ratio (PPR) under control conditions (r= 0.184, n= 39; PPR = ratio of amplitude of the second to the first EPSP (EPSP2/EPSP1) in a 10 Hz evoked train).

Reduction of unitary EPSPs by nicotine.

To examine nicotinic modulation of EPSPs, 10 μM nicotine was bath-applied for 3 min. The results for a representative pair are shown in figure 1C. Compared to the typical effect of carbachol (figure 1A), nicotine had relatively little effect on peak EPSP amplitude (also see table 1). The width of the EPSP (measured at one-half peak amplitude) did not change significantly (table 1).

At resting membrane potential, NMDA receptors are largely blocked by Mg+2. This might mask a potential NMDAR-dependent effect of nicotine on synaptic transmission, particularly because nicotine has been reported to selectively enhance transmitter release at NMDAR-only “silent” synapses in developing cortex (Aramakis and Metherate, 1998). Conversely, muscarinic receptors have been reported to mediate reduction of transmitter release preferentially at glutamatergic synapses enriched in non-NMDAR in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fernandez de Sevilla et al., 2002). To relieve the voltage-dependent block of NMDAR, we substituted an equimolar concentration of Ca+2 (increased from 2 mM to 3 mM) for Mg+2 to maintain a constant divalent cation concentration. This nominally Mg+2-free solution (0 mM Mg+2 ACSF) increased average peak amplitudes by 48% +/- 66%, although the change was not statistically significant (p>0.05, n=14, not shown) and may have been influenced by increased Ca+2 as well as reduced Mg+2 (c.f. figure 3D). EPSP width increased significantly from 23.5 +/- 4.4 ms to 37.9 +/- 9.6 ms (p<0.0005, n=12). The changes were largely reversed by 50 μM D-AP5, a selective NMDAR antagonist (in 0 mM Mg+2, EPSP amplitude with D-AP5 was 59% +/- 5% of control value, p< 0.005, n= 6, not shown).

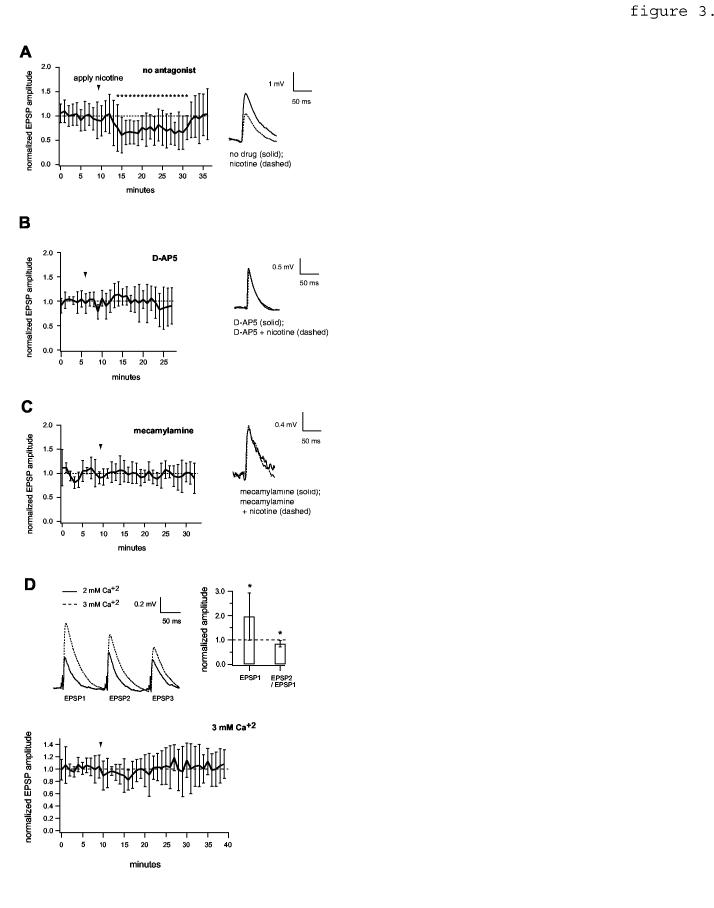

3.

NMDA receptor dependence of EPSP reduction by nicotine. A, Left, EPSP amplitude time course showing the effect of nicotine in the absence of antagonist, normalized to the value preceding nicotine (n=20 pairs). Asterisks indicate time points that differ significantly from control (p< 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-tests). Right, average traces showing the effect of nicotine on an example pair (c.f. figure 1E). Resting Vm = -67 mV. B, data obtained in the presence of 50 μM D-AP5 (n=6). For average EPSP traces (right), resting Vm = -62 mV. C, data obtained in the presence of the selective nicotinic receptor antagonist, 10 μM mecamylamine (n=7 pairs). Resting Vm = -66 mV. Note: apparent background noise seen in this example was atypical. Data in A,B,C were obtained in 0 mM Mg+2. D, Top, [Ca+2]-dependent changes in EPSP amplitude and paired-pulse ratio. Asterisks denote p< 0.05 (n=9 pairs). Bottom, effect of nicotine in ACSF containing 1 mM Mg+2 / 3 mM Ca+2 (n=6 pairs).

In Mg+2-free solution, nicotine application produced a clear synaptic effect. The peak amplitude of evoked unitary EPSPs was substantially reduced by nicotine application (figure 1E). This was consistent across the population: EPSP amplitude during nicotine application differed significantly from both baseline and washout values (figure 1F; compare the data for 1 mM Mg+2, figure 1D). In 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF, nicotine also caused a significant decrease in the width of the EPSP, measured at one-half peak amplitude (table 1). The postsynaptic cell’s average resting Vm and input resistance did not change (table 1). Like carbachol-dependent EPSP reduction, the extent of EPSP reduction by nicotine was not substantially correlated with age of the animal (r= 0.36, n= 31), with EPSP amplitude measured under control conditions (r= -0.121, n= 31) or with PPR under control conditions (r= 0.175, n= 31).

A ten-fold lower concentration (1 μM nicotine; 3-5 min in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF) had less effect: EPSP amplitude was reduced to 87% +/- 28% of control values (n=8, p>0.5, not shown). Therefore, 10 μM nicotine was used in subsequent experiments.

Pharmacological characterization of carbachol- and nicotine-dependent EPSP reduction.

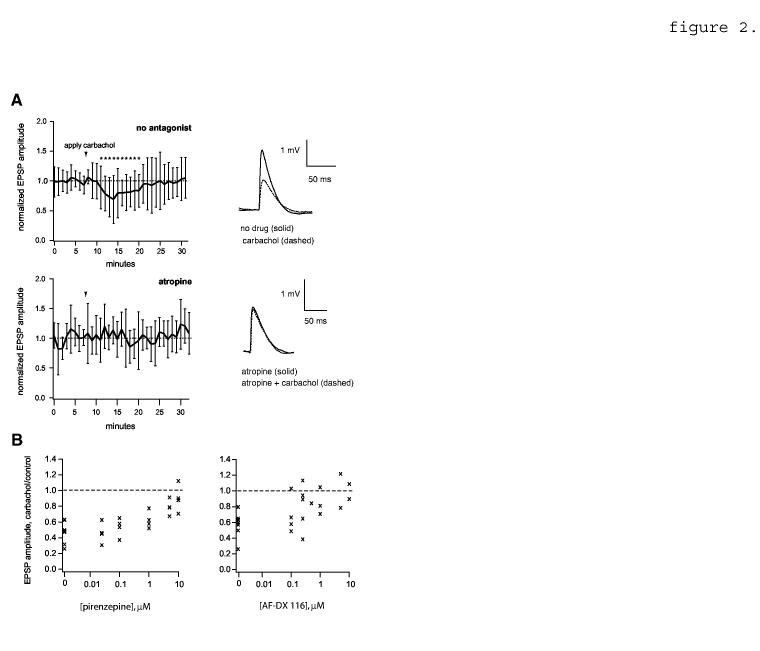

EPSP reduction by carbachol was blocked by 1 μM atropine (figure 2A; compare upper and lower panels), indicating the involvement of muscarinic receptors. Similar results were obtained previously with EPSPs evoked with extracellular stimulation of afferents (Hasselmo and Bower, 1992; Vidal and Changeux, 1993; Gil et al., 1997; Hsieh et al., 2000). Both pirenzepine (an M1 subtype-selective antagonist) and AF-DX 116 (an M2 subtype-selective antagonist) prevented carbachol-dependent EPSP reduction substantially at concentrations > 1 μM (figure 2B), which are relatively non-selective (c.f. Dörje et al., 1991; Daeffler et al., 1999). At lower concentrations, AF-DX 116 appeared to be slightly more effective than pirenzepine (e.g., at 0.1 μM and 1 μM in figure 2B). The M4-selective antagonist PD 102807 was completely ineffective at 2 μM, the highest concentration tested (n=5 pairs, not shown; c.f. Augelli-Safran et al., 1998). In contrast to the results with nicotine, removal of Mg+2 from the external medium did not result in any additional suppressive effect of carbachol (EPSP amplitude with carbachol was 78% +/- 20% of control EPSP amplitude in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF, p > 0.05 n=6, not shown). EPSP reduction by carbachol in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF was largely prevented by 1 μM atropine (EPSP = 94% +/- 22% of control, p> 0.05, n=9, not shown).

2.

EPSP reduction by carbachol; effect of muscarinic receptor antagonists. A, Top left, EPSP amplitude time course showing the effect of carbachol in the absence of 1 μM atropine (n=20 pairs). EPSPs are averaged in 1 minute bins and normalized to the mean value before carbachol application. Arrowhead shows the time of initial carbachol application (duration varied between 2 and 3 min). Asterisks indicate time points that differ significantly from control (p<0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-tests). Top right, example average traces showing the effect of carbachol on an example pair (c.f. figure 1A). Resting Vm = -64 mV. Bottom left, data obtained in the presence of 1 μM atropine (n=6 pairs). Bottom right, example traces; resting Vm = -61 mV. B, antagonism of carbachol-mediated EPSP suppression by the M1-subtype specific antagonist pirenzepine (left) and the M2 subtype-specific antagonist AF-DX 116 (right). Each point represents average peak amplitude data from one pair at the given antagonist concentration (n=7 pairs total for pirenzepine and 8 pairs for AF-DX 116). Pirenzepine was tested at 0.025, 0.1, 1, 5 and 10 μM and AF-DX 116 at 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 μM.

Data shown in figure 1 suggested that NMDAR activation was required for the suppressive effect of nicotine. This was tested further by selective NMDAR blockade. When the AMPA component was blocked with 10 μM DNQX, D-AP5 blocked the remaining NMDAR component (not shown for current clamp data, but c.f. figure 6A). Nicotine-mediated EPSP reduction (in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF) was blocked by D-AP5 (figure 3B). Conversely, carbachol-mediated EPSP reduction (in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF) persisted in the presence of 50 μM D-AP5 (n=5/5 pairs; not shown). EPSP reduction by nicotine in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF was abolished by 10 μM mecamylamine, a nonspecific nicotinic receptor antagonist (figure 3C).

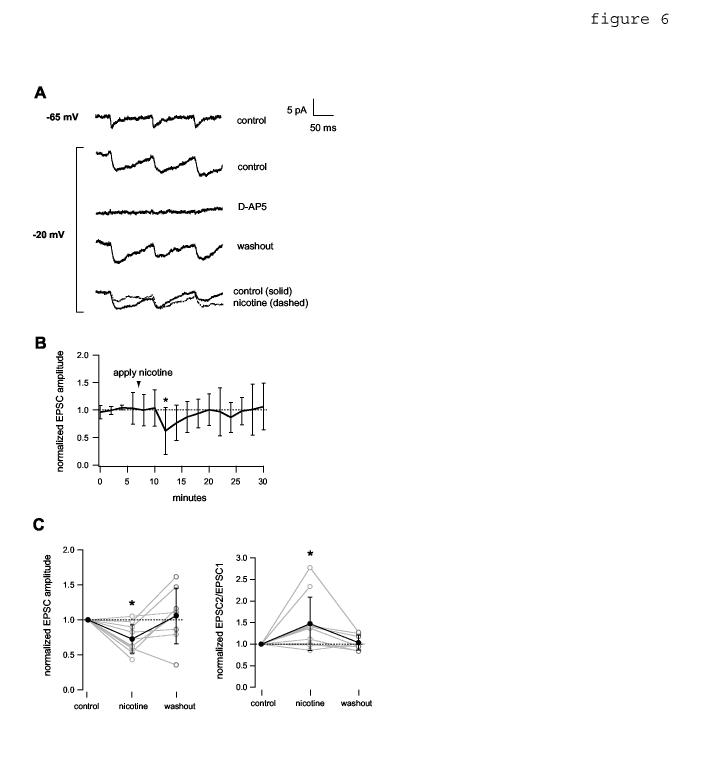

6.

Depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF permits nicotinic reduction of NMDAR-mediated EPSCs. Data were obtained in the presence of 10 μM DNQX. The soma of the postsynaptic cell was held in voltage clamp at the indicated holding potential. A, average current traces showing NMDAR-mediated EPSCs evoked by 10 Hz presynaptic stimulation. Depolarization to -20 mV enhanced the NMDAR current (compare top 2 traces). The evoked EPSC was blocked reversibly by bath-applied 50 μM D-AP5. Bottom traces, effect of bath-applied (3 min) 10 μM nicotine. B, average EPSC amplitude time course, normalized to the mean value before nicotine application (n= 7 pairs). Asterisk indicates time point that differs significantly from control (p< 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-test). C, Left, normalized EPSC amplitude data for all pairs. Mean values (filled circles) were 0.73 +/- 0.20 during nicotine and 1.05 +/- 0.40 after washout. Asterisk denotes significance relative to control (p< 0.01, n= 10 pairs). Right, normalized EPSC2/EPSC1 for all pairs. Mean values (filled circles) were 1.47 +/- 0.62 during nicotine and 1.04 +/- 0.17 after washout. Asterisk denotes significance relative to control (p< 0.05, n= 10 pairs). Connections where mean control EPSC peak amplitude was < 2.5 pA were excluded because of poor signal:noise ratio. Washout data were not obtained for two pairs.

[Ca+2] was raised from 2 mM to 3 mM in our nominally Mg+2 free medium, raising the possibility that the effect of nicotine was sensitive to a change in transmitter release probability (c.f. Maggi et al., 2004) rather than, or in addition to, Mg+2-dependent NMDAR unblocking. Prevention of the effect of nicotine by NMDAR antagonists (figure 3C) argued against this possibility, but we nevertheless tested it by increasing [Ca+2] while keeping [Mg+2] fixed at 1 mM. In figure 3D (upper panels) raising [Ca+2] from 2 mM to 3 mM caused a significant change in EPSP amplitude and in the paired-pulse ratio (PPR; the amplitude ratio of the second to the first EPSP in an evoked train), consistent with an increase in release probability (Johnston and Wu, 1995). In ACSF containing 1 mM Mg+2 and 3 mM Ca+2, nicotine had relatively little effect on EPSP amplitude (figure 3D, bottom) in comparison to its effect in ACSF containing 0 mM Mg+2 and 3 mM (figure 3A). This indicated that the effect of nicotine depended largely on the reduction in [Mg+2] rather than on the increase in [Ca+2].

Because of the nicotinic EPSP reduction appeared to depend on NMDA receptor unblocking, we predicted that the relative magnitude of the effect might increase when NMDAR responses were isolated by bath application of the AMPAR blocker, 10 μM DNQX. Somewhat surprisingly, the effect of nicotine was slightly less pronounced in the presence of DNQX (80% +/- 20% of control; p < 0.05, n=8, not shown).

Effects of carbachol and nicotine on the short-term plasticity of EPSPs.

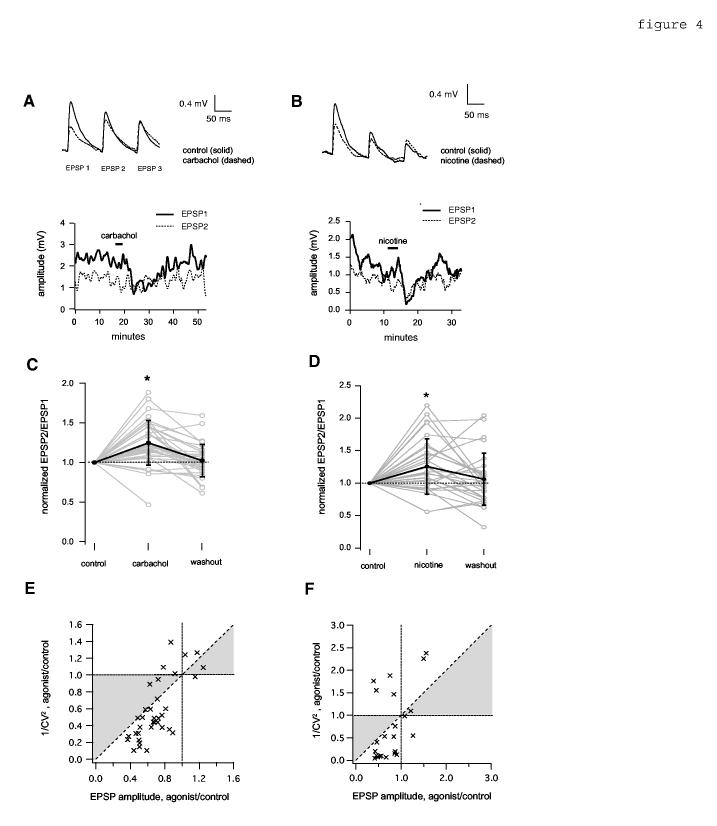

We tested whether the effects of carbachol and nicotine occur through a presynaptic mechanism by examining EPSPs evoked by repetitive presynaptic stimulation. Both carbachol (in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF) and nicotine (in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF) increased the paired-pulse ratio, by producing a greater suppressive effect on the first EPSP of a 10 Hz train than on subsequent EPSPs (figure 4A-D; table 1, “EPSP2/EPSP1”). The change in PPR was statistically significant for both carbachol and nicotine, and was reversible upon washout (figure 4C,D). Additional evidence for a presynaptic change was provided by analysis of the change in coefficient of variation relative to mean EPSP amplitude (figure 4E,F; postsynaptic change corresponds to points falling within the shaded regions (Faber and Korn, 1991; for applicability of this method in the context of paired intracellular recordings, see Sjöström et al., 2003).

4.

Effect of cholinergic agonists on short-term depression of unitary evoked EPSPs. A,C,E, show effects of carbachol in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF; B,D,F show effects of nicotine in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF. A,B, Top, average EPSPs evoked with 10 Hz suprathreshold stimulation of presynaptic cells before (solid trace) and during (dashed trace) application of carbachol (5 μM, 3 min, A) or nicotine (10 μM, 3 min, B). Resting Vm = -65 mV (A and B). Bottom, example time courses of the effect of carbachol (A) and nicotine (B) on the peak amplitude of the first EPSP (EPSP1, solid line) and second EPSP (EPSP2, dotted line). Data are plotted as a sliding boxcar average (width = 19 data points). Data are from the same experiments shown in figures 1A and 1E, respectively. The horizontal bar in the upper part of each panel indicates the drug application time. C,D, Summary of average paired-pulse ratio (EPSP2/EPSP1 peak amplitude) before (control), during application, and after washout, for carbachol, (C) and nicotine (D). Data are normalized to control values. Grey lines and open circles show values for individual pairs; black lines and filled circles with error bars show mean and S.D.. The mean normalized EPSP2/EPSP1 during carbachol (C) was 1.25 +/- 0.28, and the washout value was 1.02 +/- 0.20; the asterisk denotes significance relative to the control (p< 0.0001, n= 39), and washout (p< 0.0001, n= 36). Normalized EPSP2/EPSP1 during nicotine (D) was 1.26 +/- 0.43; the washout value was 1.06 +/- 0.40; the asterisk denotes significance relative to the control (p<0.01, n= 29), and washout (p< 0.05, n= 28). E,F. CV2 analysis of EPSP reduction by carbachol in 1 mM Mg+2 (E) and nicotine in 0 mM Mg+2 (F). Shaded area between the diagonal and Y=1 corresponds to a postsynaptic change. CV was corrected by subtraction of the mean internal noise as described in Feldmeyer et al (1999). Each data point represents one synaptically connected pair. Pairs where EPSP CV was not significantly larger than noise CV were excluded. n=35 (carbachol, E); n=23 (nicotine, F).

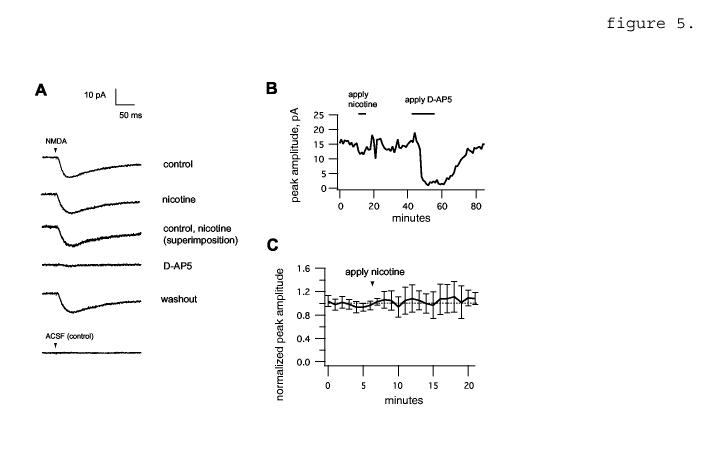

If EPSP reduction depended on reduction of transmitter release, nicotine would not be expected to grossly affect postsynaptic currents produced by application of exogenous NMDA. We tested this by applying NMDA directly to the pyramidal cell’s apical dendrite via brief pressure ejection at regular intervals to mimic presynaptic stimulation (compare Aramakis and Metherate, 1998). Transient bath application of nicotine had no apparent effect on response amplitude (figure 5).

5.

Nicotine does not affect responses to NMDA applied by pressure ejection. A, average current traces from a representative experiment. The arrowhead bar shows the time of onset of the NMDA pulse (1 mM, 20 PSI, 3 ms). Average traces are shown in the absence of any additional drug (control, top) and in the presence of bath applied 10 μM nicotine. 50 μM D-AP5 reversibly abolished NMDA-induced depolarization. Bottom trace, pressure ejection of ACSF alone produces no response. B, time course of peak voltage amplitudes from the experiment shown in A. Sliding boxcar average is shown (width = 19 points). C, average time course for nicotine (n= 6 neurons), normalized to control value.

Unblocking postsynaptic NMDA receptors by depolarization permits reduction of synaptic currents by nicotine.

The fact that nicotine did not alter postsynaptic response to applied NMDA did not rule out the possibility that postsynaptic NMDAR activity was required for nicotine’s effect in a way that was not grossly detectable as a change in the NMDAR current (see Discussion and figure 7). Because the Mg+2 block is voltage-dependent, depolarizing the postsynaptic cell (without reducing [Mg+2]) was expected to have an effect similar to removal of Mg+2 if nicotinic EPSP reduction was indeed dependent on the activity of postsynaptic NMDAR. To test this, we held the postsynaptic cell at -20 mV and recording NMDAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) evoked by presynaptic stimulation (figure 6). A fraction of synaptic contacts, at least, between connected pairs was electrotonically close enough to the soma to permit unblocking of NMDAR by this method (compare Markram et al., 1997). Bath-application of nicotine caused changes in EPSC amplitude (figure 6A,B,C) and paired-pulse ratio (figure 6C) that were comparable to the effects of nicotine in 0 mM Mg+2 ACSF (compare figure 6 to figures 1E,F, 3A, 4B,D).

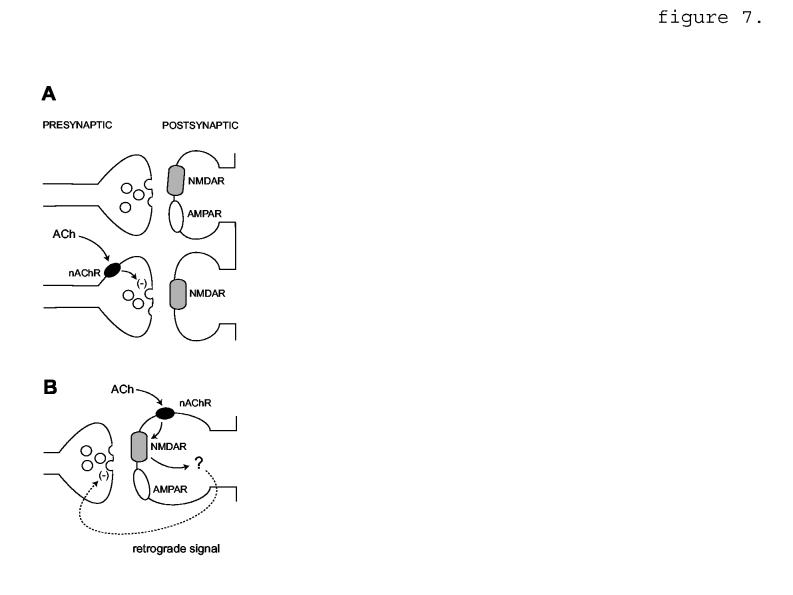

7.

Speculative diagram of two possible mechanisms for nicotinic EPSP reduction requiring NMDAR activity. A, Presynaptic nAChR are located selectively at synapses lacking postsynaptic AMPAR (lower panel). nAChR activation leads to reduction of transmitter release, denoted by (-). Modified from Metherate and Hsieh, 2004. B, nAChR are located postsynaptically at mixed AMPAR/NMDAR synapses. nAChR activation leads to NMDAR-dependent signaling via a retrograde message (dashed line) that reduces presynaptic transmitter release.

Discussion.

Using paired intracellular recording to study synaptic transmission between layer 5 pyramidal cells, we found that cholinergic agonists could reduce EPSPs by two routes. First, EPSPs were reduced by nicotine, but only under conditions favoring NMDAR activation. Second, EPSPs were reduced by activation of muscarinic receptors, an effect that did not depend on NMDAR. Nicotinic and muscarinic agonists each affected synaptic transmission at concentrations where there was negligible effect on resting Vm or cell input resistance.

Receptor types and molecular mechanisms underlying EPSP reduction.

Muscarinic receptors:

Reduction of EPSPs by carbachol in 1 mM Mg+2 was largely blocked by 1 μM atropine (fig. 2A), indicating that the effect depends on muscarinic receptors. Muscarinic EPSP reduction has been seen in studies of many CNS pathways, but the receptor subtype(s) responsible have not been unambiguously identified. Vidal and Changeux (1993) found that muscarinic reduction of EPSPs evoked by extracellular stimulation in prefrontal cortex was blocked less effectively by the M1-selective antagonist pirenzepine than by the non-selective antagonist atropine, suggesting that receptors other than the M1 subtype were responsible. In immunocytochemical studies encompassing rat (Levey et al., 1991), primate (Mrzljak et al., 1993; Mrzljak et al., 1996; Mrzljak et al., 1998) and cat sensory cortex (Erisir et al., 2001), M2 receptor staining was consistent with both pre- and postsynaptic distribution at the light microscopic level; electron microscopy has identified M2 in axon terminals and dendritic spines forming asymmetric (presumed glutamatergic) synapses (Mrzljak et al., 1993; Mrzljak et al., 1996; Erisir et al., 2001). In contrast, M1 receptors are located postsynaptically in cortical pyramidal cells in rat (Levey et al., 1991) and primate cortex (Mrzljak et al., 1993), but have not been seen presynaptically. In support of a role for M2 receptors, our data suggest that the M2 antagonist AF-DX 116 prevents EPSP reduction by carbachol somewhat more effectively than the M1 antagonist, pirenzepine (fig. 2B). Other than M1 and M2, M4 is the most abundant muscarinic receptor subtype in rat brain (Levey et al., 1991). But high concentrations of the M4-specific antagonist PD 102807 did not affect carbachol-mediated EPSP suppression, so involvement of M4 subunits appears unlikely.

In 0 mM Mg+2, carbachol might have been expected to cause additional EPSP reduction via nicotinic receptors, based on the fact that nicotine reduced EPSPs in 0 mM Mg+2 but not in 1 mM Mg+2 (fig. 1C-F). However, the effect of carbachol in 0 mM Mg+2 was not significantly different from its effect in 1 mM Mg+2, and was blocked by atropine. This indicates that carbachol acted as a de facto muscarinic agonist in our system, consistent with several previous reports (see Results).

Nicotinic receptors:

Previous electrophysiological studies of nicotinic modulation of cortical glutamatergic synapses have found either no effect, or a strictly facilitative effect (Vidal and Changeux, 1993; Aramakis and Metherate, 1998) (Gil et al., 1997). Our finding that nicotine can reversibly reduce glutamatergic EPSPs therefore reveals a previously unrecognized activity of nicotine in sensory cortex; (but see Maggi et al., 2004, discussed below). The difficulty of selectively activating intra-cortical pathways by extracellular stimulation may explain why the suppressive action of nicotine was not observed previously. Moreover, our results show that conditions favoring NMDAR activation are necessary in order to detect nicotine-dependent EPSP reduction in slice recordings. Another possibility is that EPSP reduction by nicotine might be a feature of local but not longer-distance intra-cortical connections. Analogously, nicotine might enhance EPSPs in the superficial layers, such as connections between layer 4 spiny stellate cells and layer 2/3 pyramidal cells, while reducing EPSPs between layer 5 pyramidal cells. In this scheme, nicotinic activity would differently modulate early versus late stages of processing within a cortical column. Also, the effect might be developmentally transient, because our data were taken from animals within or near the critical period for sensory plasticity (Fox, 1992; Glazewski and Fox, 1996).

We conclude that nicotinic EPSP reduction happens through presynaptic reduction of transmitter release, based on the analysis of paired-pulse ratio (fig. 4A-D) and coefficient of variation (fig. 4E,F). Nicotinic EPSP reduction also required NMDAR unblocking via removal of Mg+2 from the external medium (fig. 1C-F), or depolarization of the postsynaptic cell (fig. 6). In addition, nicotinic EPSP reduction was prevented by the NMDAR antagonist, D-AP5 (fig. 3A,B). One possible explanation for these observations is that nicotine preferentially reduces glutamate release at functionally “silent” sites that lack detectable AMPAR. Nicotinic receptors might be located selectively at terminals presynaptic to NMDAR-only sites (figure 7A). An analogous mechanism has been proposed for NMDAR-selective nicotinic enhancement of EPSPs evoked in presumed thalamo-cortical synapses of developing auditory cortex (Aramakis and Metherate, 1998), and for apparent AMPAR-selective muscarinic modulation in hippocampus (Fernandez de Sevilla et al., 2002).

However, not all our data fit this model. If nicotinic modulation in our system targets postsynaptic sites enriched in NMDAR, EPSP reduction (normalized to control) would be more prominent when non-NMDAR are blocked by DNQX. Instead, we found that nicotinic reduction of the isolated NMDAR response, either in 0 mM Mg+2 (not shown) or with the postsynaptic cell depolarized under voltage clamp (fig. 6) was not conspicuously greater than nicotinic reduction of the combined NMDAR+AMPAR response (fig. 1E-F, 3A). Quantitative comparisons across different conditions may be of limited validity in our system because the effects we measured were transient, reflecting limited bath application time and possible receptor desensitization, particularly of nicotinic receptors (reviewed in Giniatullin et al., 2005). But taken at face value, these data argue against selective reduction of the AMPAR-dependent component.

Therefore an alternative explanation for our findings is that glutamate release is not modulated selectively at postsynaptically NMDAR-enriched sites, but instead that modulation of release occurs at mixed AMPAR+NMDAR sites, and is a result of a change in NMDAR activity (figure 7B). The details of this model are more speculative at present than the details of the first model (figure 7A). Our results suggest an obligatory role for postsynaptic NMDAR, because depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron elicits nicotine-dependent EPSP reduction (fig. 6). We found no grossly appreciable effect of nicotine on currents produced by exogenous NMDA application (fig. 5), although it is possible that a selective synaptic effect was masked by responses of extrasynaptic NMDAR, whose subunit composition may differ from that of synaptic NMDAR (Stocca and Vicini, 1998; Tovar and Westbrook, 1999), and which might not respond to nicotinic modulation in the same way as synaptic NMDAR. There is evidence that nicotinic activity can affect postsynaptic NMDAR activity by a calmodulin-dependent process (Fisher and Dani, 2000). Postsynaptic NMDAR modulation could then affect the presynaptic terminal via a diffusible agent such as nitric oxide; nitric oxide synthase has been identified in cortex within dendritic spines that contain NMDAR (Aoki et al., 1997) and nitric oxide has been linked to NMDAR activation and modulation of presynaptic glutamate release (Montague et al., 1994; Garthwaite and Boulton, 1995). The model does not exclude a role for presynaptic NMDAR, which have been identified by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry in rat visual cortex (Aoki et al., 1994) and elsewhere in cortex (DeBiasi et al., 1996; Charton et al., 1999), and have been implicated in timing-based long-term depression at synapses between layer 5 pyramidal cells of rat visual cortex (Sjöström et al., 2003; c.f. Berretta and Jones, 1996).

It is also possible that nicotine reduces EPSPs indirectly by enhancing GABA release from inhibitory neurons (see references cited in the Introduction), with consequent reduction of glutamate release (Bonanno et al., 1997; Torres-Escalante et al., 2004). We can not rule out this possibility, although some indirect evidence argues against it. Baseline spontaneous activity in our recordings was generally low, and we did not find evidence for spontaneous inhibition emerging as a result of agonist application, although inhibitory PSPs may have been difficult to detect due to the composition of our solutions. Additionally, we have recorded from both fast-spiking (FS) and low-threshold-spiking interneurons, alone and also receiving synaptic input with pyramidal neurons (n=10 pairs for FS and 4 pairs for LTS), and carbachol or nicotine application under the conditions of the present study did not elicit spontaneous or evoked firing (via stimulation of a presynaptic pyramidal neuron) in either interneuron type.

A recent study of using slices from neonatal (P1-P7) rats found that transient nicotine application produced long-term depression (LTD) of EPSCs evoked in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells by stimulation of Schaffer collaterals (Maggi et al., 2004). Unlike the results of that study, nicotinic EPSP reduction in the present case was largely reversible. Maggi et al. (2004) also found that nicotine can either potentiate or depress synaptic transmission, depending on whether transmitter release probability (P) was low or high, respectively; changing P by increasing extracellular [Ca+2] and reducing [Mg+2] could convert the effect of nicotine at a given synapse from LTP induction to LTD induction, or vice versa. In the present study, increasing [Ca+2] without reducing [Mg+2] did not elicit nicotine-dependent EPSP reduction (fig. 3D). We could not determine P directly in most instances because it was difficult to distinguish very weak EPSPs from failures, but all the connections in our data set were unambiguously reliable (P> 0.5), It is possible that low P connections in respond to nicotine differently from those we have studied here.

NMDAR activity is reduced but not absent in 1 mM Mg+2, relative to 0 mM Mg+2; the NMDAR component has been reported to compose 17% the voltage-time interval of the EPSP at -60 mV in connections between layer 5 pyramidal neurons in slices from P14-P16 rats, recorded in 1 mM Mg+2 (Markram et al., 1997). Based on this, we would expect (in principle) some degree of EPSP reduction by nicotine even in 1 mM Mg+2, whereas our pooled data showed no such effect (fig. 1D). We speculate that the effect of nicotine under these conditions was too small to be statistically evident, given the limited number of samples (n=41 pairs). A suggestion of nicotinic EPSP suppression in 1 mM Mg+2 ACSF was seen in some individual instances (e.g. figure 1C).

Sources of variability in the data:

We did not find correlations between modulatory effects and other parameters such as age of the animal, baseline EPSP amplitude or PPR, so the foregoing discussion all pairs were assumed to belong to ahomogeneous population, However, the data give some indication of variation in modulatory effect among pairs. For instance, the histogram of nicotine’s effect in 1 mM Mg+2 is approximately Gaussian and centered on 1 (fig. 1D, right), but some individual pairs showed a reversible EPSP enhancement by nicotine while others showed a reversible reduction (fig. 1D, left). In view of this, it remains possible that EPSP modulation is correlated with differences in cell type or connectivity that were not examined here. For example, we did not make a morphometric distinction between neurons with simple versus complex apical dendritic tufts, both of which classes may be regular-spiking (Franceschetti et al., 1998) but may differ in their synaptic properties (Angulo et al., 2003). Individual pairs within layer 5 could also represent different circuit elements, e.g. intra-versus intercolumnar connections could be modulated differently. Possible functional consequences are discussed in the next section.

Cholinergic reduction of local excitatory transmission: functional aspects.

It has been proposed that recurrent excitation in the visual cortex influences neuronal selectivity and responsiveness to stimulus properties including orientation (Ben-Yishai et al., 1995; Douglas et al., 1995; Somers et al., 1995), direction (Douglas et al., 1995) and spatial phase (Chance et al., 1999). Suppression of local excitatory connections by ACh or other cholinergic agonists could alter the receptive field properties of cortical sensory neurons. Depending on the level of cholinergic activity, the muscarinic pathway would act to reduce the effects of recurrent excitation: lateral spread of excitation, and cortical amplification of sensory input.

The nicotinic pathway would act similarly, but with an additional feature: because of its dependence on NMDA receptor activation, nicotinic reduction of recurrent excitation would be turned on by heightened sensory excitation. Such activity-dependent nicotinic suppression could serve as a cellular mechanism underlying the contraction of receptive field size in macaque V1 in response to increased stimulus contrast (Sceniak et al., 1999). The latter effect was not correlated with changes in surround inhibition, leading the authors to propose a contrast-dependent suppression of lateral excitatory connections. The changes of cortical receptive field properties caused by either the muscarinic or the nicotinic pathway could contribute to the improvements in perceptual ability that have been attributed to ACh (reviewed in Hasselmo, 1995). However, our slice data were derived from relatively young animals. It remains to be seen whether nicotinic EPSP reduction persists in adulthood. If it is restricted to the first few weeks after birth, nicotinic EPSP reduction could still be significant in vivo, by shaping cortical receptive field properties during the critical period.

EPSP reduction by both nicotine and carbachol in our system acted by a presynaptic mechanism and thus had a decreasing effect on the amplitude of each successive EPSP in a train. As a result, this type of synaptic modulation might have subtle effects on information coding (Abbott et al., 1997; Markram and Tsodyks, 1996a, b; Tsodyks and Markram, 1997), rather than simply decreasing communication among locally connected neurons.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Anita Disney and Robert Shapley for critical reading and discussion, and Veeravan Mahadomrongkul for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 NS41091 and R01 NEI 13145-01 to CA and ADR, 5 F32 NS045452-01A1 to RBL, P30 EY13079 Core grant (PI: JA Movshon), and Office of Naval Research Grant BAA 99-019 (PI: P Lennie).

References:

- Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB. Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science. 1997;275:220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo MC, Staiger JF, Rossier J, Audinat E. Distinct local circuits between neocortical pyramidal cells and fast-spiking interneurons in young adult rats. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:943–953. doi: 10.1152/jn.00750.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Rhee J, Lubin M, Dawson TM. NMDA-R1 subunit of the cerebral cortex co-localizes with neuronal nitric oxide synthase at pre- and postsynaptic sites and in spines. Brain Res. 1997;750:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Venkatesan C, Go CG, Mong JA, Dawson TM. Cellular and subcellular localization of NMDA-R1 subunit immunoreactivity in the visual cortex of adult and neonatal rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5020–5222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramakis VB, Metherate R. Nicotine selectively enhances NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission during postnatal development in sensory neocortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8485–8495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08485.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe JH, McKenna TM, Weinberger NM. Cholinergic modulation of frequency receptive fields in auditory cortex II. Frequency-specific effects of anticholinesterases provide evidence for a modulatory action of endogenous ACh. Synapse. 1989;4:44–54. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. Muscarinic receptors mediating depression and long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;492:479–493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augelli-Szafran CE, Jaen JC, Moreland DW, Nelson CB, Penvose-Yi JR, Schwarz RD. Identification and characterization of m4 selective muscarinic antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:1991–1996. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yishai R, Bar-Or RL, Sompolinsky H. Theory of orientation tuning in visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3844–3848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta N, Jones RSG. Tonic facilitation of glutamate release by presynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate autoreceptors in the entorhinal cortex. Neuroscience. 1996;75:339–344. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G, Fassio A, Schmid G, Severi P, Sala R, Raiteri M. Pharmacologically distinct GABAB receptors that mediate inhibition of GABA and glutamate release in human neocortex. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:60–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JH, Taylor P. Muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists. In: Hardman JG, Gilman AG, Limbird LA, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 9th Edition McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chance FS, Abbott LF, Reyes AD. Gain modulation from background synaptic input. Neuron. 2002;35:773–782. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance FS, Nelson SB, Abbott LF. Complex cells as cortically amplified simple cells. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:277–282. doi: 10.1038/6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charton JP, Herkert M, Becker CM, Schröder H. Cellular and subcellular localization of the 2B-subunit of the NMDA receptor in the adult rat telencephalon. Brain Res. 1999;816:609–617. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe E, Roebuck A, Staiger JF, Lavery DJ, Charpak S, Audinat E. Two types of nicotinic receptors mediate an excitation of neocortical layer I interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1318–1327. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daeffler L, Schmidlin F, Gies J-P, Landry Y. Inverse agonist activity of pirenzepine at M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. British J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1246–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBiasi S, Minelli A, Melone M, Conti F. Presynaptic NMDA receptors in the neocortex are both auto- and heteroreceptors. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2773–2776. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611040-00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Krnjevic K, Steriade M, editors. Acetylcholine in the Cerebral Cortex. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars J, West DC, Thomson AM. Relationships between morphology and physiology of pyramid-pyramid single axon connections in rat neocortex in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;478(Pt 3):423–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörje F, Wess J, Lambrecht G, Tacke R, Mutschler E, Brann MR. Antagonist binding profiles of five cloned human muscarinic receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;256:727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Koch C, Mahowald M, Martin KA, Suarez HH. Recurrent excitation in neocortical circuits. Science. 1995;269:981–985. doi: 10.1126/science.7638624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Levey AI, Aoki C. Muscarinic receptor M(2) in cat visual cortex: laminar distribution, relationship to gamma-aminobutyric acidergic neurons, and effect of cingulate lesions. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:168–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber DS, Korn H. Applicability of the coefficient of variation method for analyzing synaptic plasticity. Biophys J. 1991;60:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer D, Egger V, Lubke J, Sakmann B. Reliable synaptic connections between pairs of excitatory layer 4 neurones within a single ‘barrel’ of developing rat somatosensory cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 1999;521(Pt 1):169–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez de Sevilla D, Cabezas C, Oshima de Prada A, Sanchez-Jimenez A, Buno W. Selective muscarinic regulation of functional glutamatergic Schaffer collateral synapses in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 2002;545:51–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JL, Dani JA. Nicotinic receptors on hippocampal cultures can increase synaptic glutamate currents while decreasing the NMDA-receptor component. Neuropharmacol. 2000;39:2756–2769. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1826–1838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01826.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschetti S, Sancini G, Panzica F, Radici C, Avanzini G. Postnatal differentiation of firing properties and morphological characteristics in layer V pyramidal neurons of the sensorimotor cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1013–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J, Boulton CL. Nitric oxide signaling in the central nervous system. Ann Rev Physiol. 1995;57:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19:679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R, Listri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazewski S, Fox K. Time course of experience-dependent synaptic potentiation and depression in barrel cortex of adolescent rats. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1714–1729. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.4.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME. Neuromodulation and cortical function: modeling the physiological basis of behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1995;67:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00113-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Bower JM. Cholinergic suppression specific to intrinsic not afferent fiber synapses in rat piriform (olfactory) cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1222–1229. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa K, Armstrong WE. A versatile means of intracellular labeling: injection of biocytin and its detection with avidin conjugates. J Neurosci Meth. 1988;25:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(88)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CY, Cruikshank SJ, Metherate R. Differential modulation of auditory thalamocortical and intracortical synaptic transmission by cholinergic agonist. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6106–6116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Wu SM. Foundations of Cellular Neurophysiology. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y. Selective cholinergic modulation of cortical GABAergic cell subtypes. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1743–1747. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Fukuda M, Tsumoto T. Acetylcholine suppresses the spread of excitation in the visual cortex revealed by optical recording: possible differential effect depending on the source of input. Euro J Neurosci. 1999;11:3587–3609. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krnjevic K, Pumain R, Renaud L. The mechanism of excitation by acetylcholine in the cerebral cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 1971;215:247–268. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi L, Sola E, Minneci F, Le Magueresse C, Changeux J-P, Cherubini E. Persistent decrease in synaptic efficacy induced by nicotine at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses in the immature rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 2004;559:863–874. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann EO, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Greenfield SA. Cholinergic modulation of the spatiotemporal pattern of hippocampal activity in vitro. Neuropharmacol. 2005;48:118–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Lubke J, Frotscher M, Roth A, Sakmann B. Physiology and anatomy of synaptic connections between thick tufted pyramidal neurones in the developing rat neocortex. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;500:409–440. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Tsodyks M. Redistribution of synaptic efficacy: a mechanism to generate infinite synaptic input diversity from a homogeneous population of neurons without changing absolute synaptic efficacies. J Physiol (Paris) 1996a;90:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(97)81429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Tsodyks M. Redistribution of synaptic efficacy between neocortical pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1996b;382:807–810. doi: 10.1038/382807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA. Neurotransmitter actions in the thalamus and cerebral cortex and their role in neuromodulation of thalamocortical activity. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;39:337–388. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Prince DA. Mechanisms of action of acetylcholine in the guinea-pig cerebral cortex in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1986;375:169–194. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna TM, Ashe JH, Weinberger NM. Cholinergic modulation of frequency receptive fields in auditory cortex: I. Frequency-specific effects of muscarinic agonsists. Synapse. 1989;4:30–43. doi: 10.1002/syn.890040105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherate R, Ashe JH. Synaptic interactions involving acetylcholine, glutamate, and GABA in rat auditory cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1995;107:59–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00228017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherate R, Hsieh C. Synaptic mechanisms and cholinergic regulation in auditory cortex. In: Descarries L, Krnjevic K, Steriade M, editors. Acetylcholine in the Cerebral Cortex. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2004. pp. 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metherate R, Tremblay N, Dykes RW. The effects of acetylcholine on response properties of cat somatosensory cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1231–1252. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.4.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Gancayco CD, Winn MJ, Marchase RB, Friedlander MJ. Role of NO production in NMDA receptor-mediated neurotransmitter release in cerebral cortex. Science. 1994;263:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.7508638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L, Levey AI, Belcher S, Goldman-Rakic PS. Localization of the m2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor protein and mRNA in cortical neurons of the normal and cholinergically deafferented rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1998;390:112–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L, Levey AI, Goldman-Rakic PS. Association of m1 and m2 muscarinic receptor proteins with asymmetric synapses in the primate cerebral cortex: morphological evidence for cholinergic modulation of excitatory neurotransmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5194–5198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L, Levey AI, Rakic P. Selective expression of m2 muscarinic receptor in the parvocellular channel of the primate visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7337–7340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldford E, Castro-Alamancos MA. Input-specific effects of acetylcholine on sensory and intracortical evoked responses in the “barrel cortex” in vivo. Neuroscience. 2003;117:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, Cauli B, Tzuzuki K, Lambolez B, Rossier J, Audinat E. Selective excitation of subtypes of neocortical interneurons by nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5228–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Sakmann B. Developmental switch in the short-term modification of unitary EPSPs evoked in layer 2/3 and layer 5 pyramidal neurons of rat neocortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3827–3835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03827.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sceniak MP, Ringach DL, Hawken MJ, Shapley R. Contrast’s effect on spatial summation by macaque V1 neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:733–739. doi: 10.1038/11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström PJ, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Neocortical LTD via coincident activation of presynaptic NMDA and cannabinoid receptors. Neuron. 2003;39:641–654. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers DC, Nelson SB, Sur M. An emergent model of orientation selectivity in cat visual cortical simple cells. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5448–5465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05448.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sompolinsky H, Shapley R. New perspectives on the mechanisms for orientation selectivity. Curr Op Neurobiol. 1997;7:514–522. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Timofeev I, Grenier F. Natural waking and sleep states: a view from inside neocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1969–1985. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocca G, Vicini S. Increased contribution of NR2A subunit to synaptic NMDA receptors in developing rat cortical neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;507:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.013bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Dodt HU, Sakmann B. Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflugers Archiv - Euro J Physiol. 1993;423:511–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00374949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AM, Deuchars J, West DC. Large, deep layer pyramid-pyramid single axon EPSPs in slices of rat motor cortex display paired pulse and frequency-dependent depression, mediated presynaptically and self-facilitation, mediated postsynaptically. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2354–2369. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Escalante JL, Barral JA, Ibarra-Villa MD, Perez-Burgos A, Gongora-Alfaro JL, Pineda JC. 5-HT1A, 5-HT2, and GABAB receptors interact to modulate neurotransmitter release probability in layer 2/3 somatosensory rat cortex as evaluated by the paired pulse protocol. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:268–278. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar KR, Westbrook GL. The incorporation of NMDA receptors with a distinct subunit composition at nascent hippocampal synapses in vitro. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4180–4188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04180.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsodyks MV, Markram H. The neural code between neocortical pyramidal neurons depends on neurotransmitter release probability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:719–723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C, Changeux JP. Nicotinic and muscarinic modulations of excitatory synaptic transmission in the rat prefrontal cortex in vitro. Neuroscience. 1993;56:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90558-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Stuart GJ. Site independence of EPSP time course is mediated by dendritic Ih in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;83:3177–3182. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang A, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Cholinergic switching within neocortical inhibitory networks. Science. 1998;281:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]