Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the best available evidence on volume-outcome effect of pancreatic surgery by a systematic review of the existing data and to determine the impact of the ongoing plea for centralization in The Netherlands.

Summary Background Data:

Centralization of pancreatic resection (PR) is still under debate. The reported impact of hospital volume on the mortality rate after PR varies. Since 1994, there has been a continuous plea for centralization of PR in The Netherlands, based on repetitive analysis of the volume-outcome effect.

Methods:

A systematic search for studies comparing hospital mortality rates after PR between high- and low-volume hospitals was used. Studies were reviewed independently for design features, inclusion and exclusion criteria, cutoff values for high and low volume, and outcome. Primary outcome measure was hospital or 30-day mortality. Data were obtained from the Dutch nationwide registry on the outcome of PR from 1994 to 2004. Hospitals were divided into 4 volume categories based on the number of PRs performed per year. Interventions and their effect on mortality rates and centralization were analyzed.

Results:

Twelve observational studies with a total of 19,688 patients were included. The studies were too heterogeneous to allow a meta-analysis; therefore, a qualitative analysis was performed. The relative risk of dying in a high-volume hospital compared with a low-volume hospital was between 0.07 and 0.76, and was inversely proportional to the volume cutoff values arbitrarily defined. In 5 evaluations within a decade, hospital mortality rates were between 13.8% and 16.5% in hospitals with less than 5 PRs per year, whereas hospital mortality rates were between 0% and 3.5% in hospitals with more than 24 PRs per year. Despite the repetitive plea for centralization, no effect was seen. During 2001, 2002, and 2003, 454 of 792 (57.3%) patients underwent surgery in hospitals with a volume of less than 10 PRs per year, compared with 280 of 428 (65.4%) patients between 1994 and 1996.

Conclusions:

The data on hospital volume and mortality after PR are too heterogeneous to perform a meta-analysis, but a systematic review shows convincing evidence of an inverse relation between hospital volume and mortality and enforces the plea for centralization. The 10-year lasting plea for centralization among the surgical community did not result in a reduction of the mortality rate after PR or change in the referral pattern in The Netherlands.

This systematic review shows convincing evidence of an inverse relation between hospital volume and mortality after pancreatic resection. Nevertheless, the 10-year lasting plea for centralization of pancreatic resection in The Netherlands did not result in a reduction of the mortality rate or change in the referral pattern.

Pancreatic resection (PR) is the only treatment option with curative intent for pancreatic and periampullary malignancy and is considered a high-risk surgical procedure with considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality.1–3 Given the limited number of long-term survivors, minimization of surgery-related mortality and morbidity is imperative.

Hospital mortality rate after PR has decreased during the last decades, although there is a considerable variation in statewide and nationwide surveys.4 In large series from specialized centers, operative mortality rates vary from 0% to 4%.1–3 These figures are in sharp contrast with a large survey from the United Kingdom that revealed a mortality rate after PR of 28% in a 10-year period.5 These differences in outcome cannot be explained by patient-dependent variables alone.

Numerous studies have shown that several high-risk surgical procedures can be performed with a lower postoperative mortality rate in high-volume centers compared with low-volume centers.6–10 This volume-outcome effect has underlined the importance of centralization.4,11–25 Although not generally accepted in the United States,26 some states successfully do centralize. In the state of Maryland, centralization of PR increased gradually in the 1990s and was associated with a decrease in the statewide hospital mortality and costs.17 This shift toward centralization was partly patient-driven and occurred without much interference of healthcare providers or government.26 In European countries, hardly any sign of centralization has been reported so far.

Analysis of mortality, based on the independent nationwide registry of mortality after surgical procedures which started in 1994, has led to a plea for centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in The Netherlands, where access to tertiary referral centers is easy. At different time points, the available data on the volume-outcome effect after PD were published in national and international journals and presented at various meetings, leading to profound discussions on the consequences of centralization of PD in The Netherlands.15,27 Proponents were generally surgeons in high-volume referral centers with low mortality rates, whereas opponents mainly came from low-volume hospitals, some showing excellent outcome in small series.

Studies that plea for centralization are received with reluctance. The scientific validity of these publications is questioned because they should reflect selection bias since they are based on data from large academic centers, single states, or selected patients.22,23,25,28 Since randomization of patients between high- and low-volume hospitals is not feasible, a systematic review of the data from independent national routine health registries was performed to minimize the introduction of bias. Also, in the present study, the effect of the ongoing plea for centralization on the hospital mortality after PD and referral pattern in The Netherlands was studied.

METHODS

Systematic Review

Study Identification

A search of the medical databases Medline and Embase (1966 until 2004) and the Cochrane Library (1996 until 2004) was performed. Search algorithms combined the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and key words “pancreaticoduodenectomy,” “resection,” “periampullary tumor,” “pancreatic cancer,” “pancreatic neoplasm,” “perioperative mortality,” “hospital mortality,” and “hospital volume.” Combinations of these terms were used depending on the requirements of the database. Also the “related articles” feature of PubMed was used. The search was limited to English language publications on human subjects. A manual cross-reference search of the bibliographies of relevant papers was carried out to identify publications for possible inclusion. No unpublished data or abstracts were used.

Study Selection

All studies comparing mortality rates of patients undergoing a PR between hospitals with different volumes were considered for inclusion. Reports on data from single institutions were not included. The outcome measure, hospital or 30-day mortality, was required as a dependent variable. PR was defined as (pylorus preserving) pancreaticoduodenectomy or total pancreatectomy for periampullary tumors, either malignant or benign neoplasms. Hospital volume was one of the independent variables. The cutoff value used for the definition of high- and low-volume hospitals was not a selection criterion, but actual cutoff numbers had to be used.

Articles in which raw data were not available for calculation of mortality rates were excluded, for example, those using medians or quartiles as cutoff values for the different hospital volume groups. Articles describing only chronic pancreatitis were also excluded. Only the most recent publication was included when selected articles used the same or overlapping data in multiple publications.

Methodologic Quality and Data Extraction

Two authors (N.T.vH. and K.F.D.K.) performed the search independently and confirmed the eligibility of the identified studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Each individual study was evaluated to assess whether heterogeneity between patients in high- and low-volume hospitals was addressed. The included articles were categorized according to the given cutoff values used as definition for high and low volume. Four cutoff points were defined as I, II, III, and IV, representing approximately 2, 5, 10, and 20 resections per year, respectively. Multiple cutoff points were analyzed from one article if data were available.

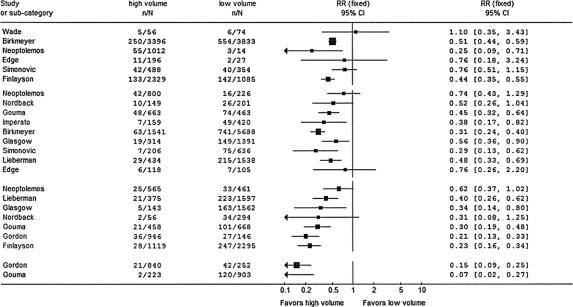

Using the 4 cutoff points, maximally 5 volume groups could be analyzed: <2, 2 to 5, 5 to 10, 10 to 20, and >20 resections per year. Relative risks for mortality compared with the lowest hospital volume group were calculated within each study. A forest plot was designed, representing the relative risks for mortality after PD in the high- and low-volume groups at each cutoff value.

Statistical Analysis

For each study, we calculated the relative risk (RR) of hospital or 30-day mortality for high-volume versus low-volume hospitals. An RR of less than 1 signifies a lower risk for mortality in a high-volume hospital than in a low-volume hospital. The χ2 and I2 test were calculated to assess heterogeneity between studies. These tests test the null hypothesis of equality of the RRs of the individual studies. The significance level was set to 0.1. In case of significant heterogeneity between studies, it is statistically not justified to pool RRs. In case of heterogeneity, we would therefore perform a systematic review and not a meta-analysis. Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 4.2 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK; available from: www.cochrane.dk) and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Effect of the Ongoing Plea for Centralization in The Netherlands

Data from the independent, nationwide registry (Prismant, Utrecht, The Netherlands) on the results of PD, including postoperative death, were obtained from 1994 to 2004. The anonymously provided mortality data were collected from each Dutch hospital except for 2 cancer institutes that performed less than 1% of the procedures. The codes used by the registry were based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM); only Code 5-526 (pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy) was evaluated to exclude potential case-mix. The parameters analyzed at regular intervals were hospital mortality, hospital volume, and age. Morbidity factors were not assessed because they were not documented in detail for all patients in the registry. Hospitals were arbitrarily divided into 4 volume categories based on the number of PRs performed per year: fewer than 5, 5 to 9, 10 to 24, and 25 or more.

RESULTS

Systematic Review

The initial search yielded 154 articles, of which 131 did not meet the inclusion criteria. The majority of excluded articles described prognostic variables (n = 51) without including data on hospital volume or mortality, covered topics such as diagnostic modalities (n = 32), and different surgical interventions in pancreatic surgery (n = 29), or treatment indications (n = 19). Also, single institution reports were not filtered out by the initial search.

Retrieval and assessment of the remaining 23 candidate articles led to exclusion of another 11 articles. In 6 articles, no exact data on the primary end point in-hospital or 30-day mortality were available.20,25,29–32 Two articles contained overlapping data (7 years overlap) from the same center, for which only the article with the most recent data was included.17,21 In another article, the high-volume hospitals performed less 2 PRs per year and was therefore excluded.18 Three articles were excluded because the range of the median hospital volume was too wide to meet one of the defined cutoff points.33–35 None of the newly found references listed in the bibliographies of the eligible studies was appropriate to be considered for inclusion.

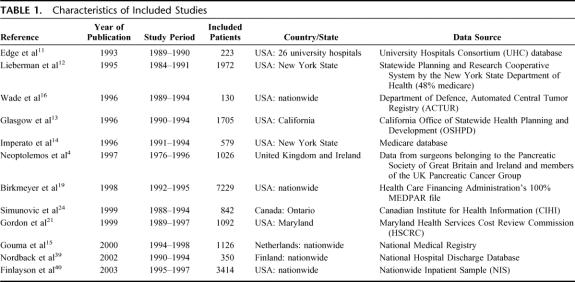

The 12 included studies in the present systematic review are stated in Table 1. The studied patients underwent PR between 1984 and 1998. The total number of evaluated patients was 19,688, varying between 130 and 7229 patients per study. Most studies were performed in the United States, one in Canada, and 3 in Europe. Data were obtained from health insurance databases, governmental registries, or university hospitals. All studies except the study by Wade et al16 used the definition in-hospital mortality rather than 30-day mortality.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Included Studies

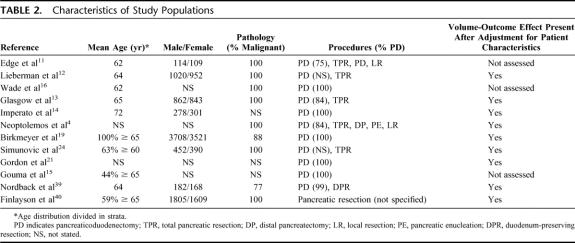

The characteristics of the populations from each study are stated in Table 2. The included studies were comparable regarding age and sex distribution. Although not specified in all studies, a PD was performed in the majority of patients and the pathology most frequently revealed a malignancy. Table 2 also shows whether the volume-outcome effect remained present after adjustment for the patient characteristics, performed by logistic regression analysis.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Study Populations

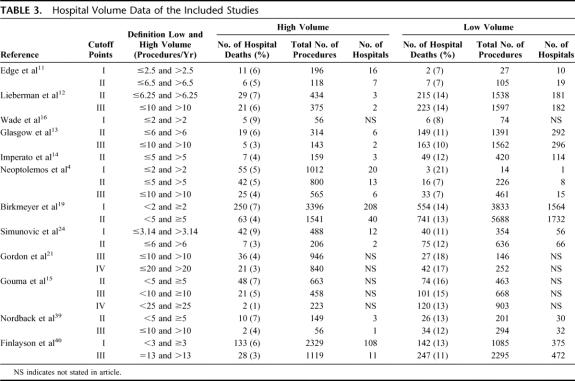

In Table 3, the hospital volume data including number of hospital deaths, procedures, hospitals involved, and definitions for high- and low-volume are given. At cutoff point I, 6 studies were analyzed with a cutoff between 2 and 3.14; 7477 patients were treated in high-volume centers and 2108 in low-volume centers, and the overall mortality was 6.6% and 19.0%, respectively. At cutoff point II, 9 studies were analyzed which used a cutoff between 5 and 6.5; 4384 patients were treated in high-volume centers and 10,668 in low-volume centers and the overall mortality was 5.2% and 12.6%, respectively. At cutoff point III, 7 studies were analyzed which used a cutoff between 10 and 13; 3662 patients were treated in the high-volume centers and 7026 in low-volume centers, and the overall mortality was 3.8% and 11.8%, respectively. At cutoff point IV, 2 studies were analyzed which used a cutoff between 20 and 25; 1063 patients were treated in the high-volume centers and 1055 in low-volume centers, and the overall mortality was 2.2% and 15.4%, respectively.

TABLE 3. Hospital Volume Data of the Included Studies

In the groups with the cutoff point of 5 and 10 resections per year, the test for heterogeneity showed a P value of 0.07 and 0.03, a χ2 of 14.36 and 13.67, and an I2 of 44.3% and 56.1%, respectively. Because of this significant heterogeneity between the studies in 2 of the 4 categories, we did not pool the relative risks and hereby did not perform a meta-analysis but rather a qualitative analysis. The forest plot in Figure 1 shows the relative risks and the 95% confidence intervals of the included studies at the 4 cutoff points. At cutoff point I, 5 of the 6 studies showed a lower relative risk of mortality in high-volume hospitals, of which 3 had statistical significance. At cutoff points II, III, and IV, all studies showed a lower relative risk of mortality in high-volume hospitals. At cutoff point II, 6 of 9 studies, at cutoff point III, 5 of 7, and in category IV, 2 of 2 studies were statistically significant in favor of high-volume hospitals. The range of the relative risks for mortality in high-volume hospitals in groups I to IV was 0.25 to 1.10, 0.29 to 0.76, 0.21 to 0.62 and 0.07 to 0.15, respectively.

FIGURE 1. Forest plot. Individual relative risk (RR) for hospital or 30-day mortality after pancreatic resection in high-volume hospitals versus low-volume hospitals. Categories I to IV represent the cutoff values for the volumes 2, 5, 10, and 20 procedures per year. N, total number of operated patients; n, number of deaths; RR, relative risk

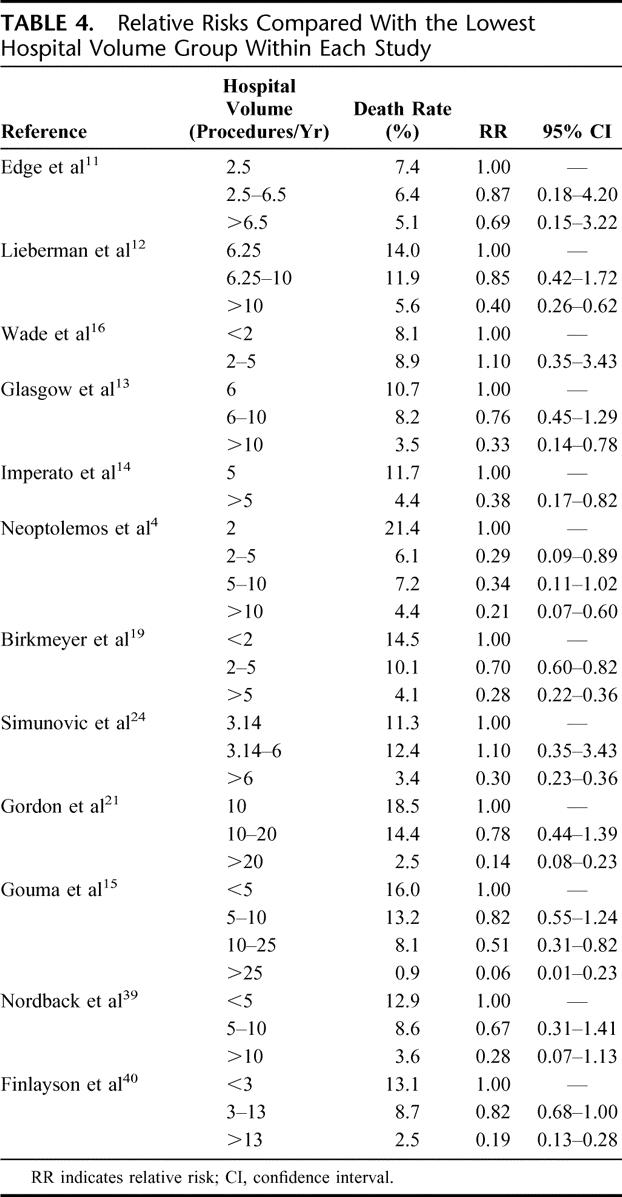

Within each individual study except for Wade et al,16 the RR for mortality in the defined volume groups decreased in higher-volume hospitals (Table 4). In 9 of the 11 studies showing a volume-outcome effect, the effect was statistically significant according to the 95% confidence interval.

TABLE 4. Relative Risks Compared With the Lowest Hospital Volume Group Within Each Study

Effect of the Ongoing Plea for Centralization in The Netherlands

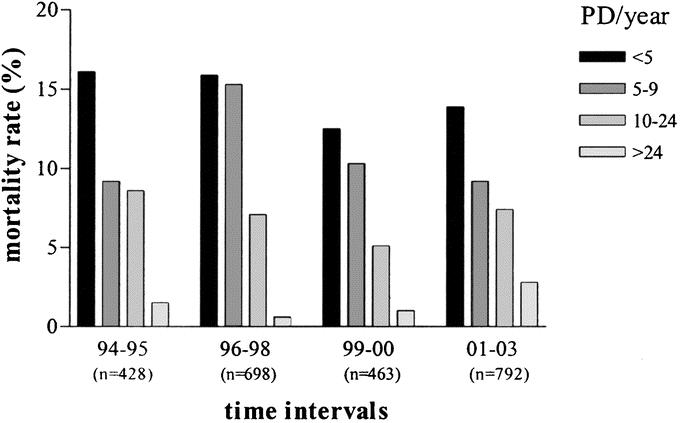

The first evaluation over the period 1994 until 1995 including 428 patients showed that the mortality was 16.1% in hospitals performing less than 5 PRs per year compared with 1.5% in hospitals performing 25 or more PRs per year. Mortality was higher in patients older than 70 years (16.2%) compared with patients younger than 55 years (6.2%) (P < 0.05).27 Consensus was reached during several national meetings (Association of Surgical Oncology, Association of Surgeons, Association of Gastroenterologists, Association of Gastroenterological Surgeons) that surgeons should as a first step at least monitor their own quality control and decide themselves whether it was justified to continue performing pancreatic surgery.

The second evaluation over 1996 until 1998 showed similar results; 15.9% mortality in hospitals performing less than 5 PRs per year compared with 0.6% mortality in hospitals performing 25 or more PRs per year.23 No change was seen in referral pattern since the first national evaluation and proponents of centralization judged this outcome as unacceptable. The generally used explanation among the opponents of centralization was that the time to implement the self-monitoring strategy had been too short to detect a change in mortality and/or referral pattern. Another argument was that surgeons from low-volume hospitals started only shortly before the second evaluation the implementation of the so-called networks: surgeons from a few low-volume hospitals performed PRs together in an attempt to improve experience. Mortality is partly caused by limited surgical experience but also by inadequate management of postoperative complications such as bleeding and leakage.

The third evaluation of 1999 to 2000 findings again showed no change in nationwide mortality rates after PD. This was discussed at the 100th year Anniversary Meeting in 2002 of the Association of Surgeons in The Netherlands. However, during the following last 3 years (2001–2003) in which again several evaluations were presented at national meetings, no major changes in mortality or referral pattern were seen.

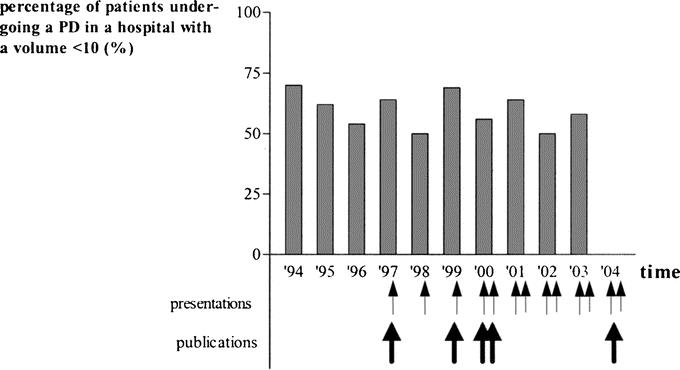

Figure 2 shows the hospital mortality in the 4 volume categories at the different time intervals between 1994 and 2004. Figure 3 shows the referral pattern to hospitals performing less than 10 PRs per year over the 10-year period. During 2001, 2002, and 2003, still 454 of 792 (57.3%) patients underwent surgery in hospitals with a volume of less than 10 PRs per year, compared with 280 of 428 (65.4%) patients between 1994 and 1996. The volume categories showed identical results.

FIGURE 2. Hospital mortality in the 4 volume categories at the different time intervals (1994–1995, 1996–1998, 1999–2000, 2001–2003).

FIGURE 3. Referral pattern to hospitals performing less than 10 PDs per year over a 10-year period (1994–2004). The arrows indicate the interventions by means of national or international presentations and publications.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review shows convincing evidence of an inverse relation between hospital volume and mortality after PR regardless of any cutoff value. The RR of mortality in a high-volume compared with a low-volume hospital varied between 0.07 and 0.76 in 11 of the 12 included studies. Moreover, a proportional trend was seen between the RR for hospital mortality and an increasing hospital volume cutoff.

Our findings were consistent with the “practice makes perfect” hypothesis originally proposed by Luft et al in 1979.36 Inverse relationships between hospital volume and mortality have long been recognized and are strongest in high-risk surgical procedures such as PR.7 Although we initially intended to perform a meta-analysis, we did not pool the reported data of the 12 included studies because of their heterogeneity. Nevertheless, we think that this systematic review reflects real differences because the effect is evident and uniform in a population of nearly 20,000 patients. Only one study did not point at a substantial benefit for patients undergoing a PR in high-volume hospitals. This study was based on relatively small series from hospitals performing around 2 resections per year.16

The results of the present systematic review should be interpreted in light of the best available evidence. Only observational data concerning the effect of hospital volume on outcome after PR could be used since RCTs are obviously not feasible. To make correct inferences, we should carefully consider multiple explanations for volume-outcome associations. Volume is not a formal indicator of quality but rather a structural characteristic.37 Selection of patients, preoperative treatment, the skills of the surgical team and critical care specialists, and postoperative care might underlie differences in outcome.

In 9 of 12 individual studies, logistic regression analysis showed that the hospital volume effect was not caused by selection bias. The assumption that low-volume hospitals generally treat older patients with an advanced tumor stage is not supported by the available literature. One could also put forward that the more complicated patients are generally referred to specialized centers.19 The effect of surgeon's volume in view of better outcomes has been studied in several high-risk surgical procedures. In a recent study, surgeon's volume accounted for 55% of the apparent effect of the hospital volume in PR.32 We think that hospital volume enhances the level of all above-mentioned factors by increasing the experience of the surgical and interdisciplinary treatment teams.

Studies included in the present review relied on administrative data, which could be limited by coding accuracy and data entry. Some studies were based on publicly available discharge data from a single state in the United States21 or were based on information from one selected healthcare database (ie, Medicare) of which all patients were older than 65 years.18,19 A biased view could also be generated by hospitals with a small sample size because of their proper chance on low mortality rates. After long-term registration, the best hospitals in the past might become worst hospitals in the future. Another argument against the available evidence in favor of treatment in high-volume hospitals is publication bias. To obtain methodologically better evidence, data should preferably be obtained from nationwide independent central registries, including all patients undergoing a PR. This requires a considerable effort from clinicians and is expensive.

The results of this systematic review are thus strongly in favor of centralization of PRs, although the consequences are unknown as well as the advised number of procedures. The Leapfrog Group, a coalition of more than 150 public and private organizations that provide healthcare benefits in the United States, was created to reduce preventable medical deaths by launching the concept of Evidence Based Hospital Referral. Safety Standards based on the Medicare database, including annual hospital volume, were defined for several high-risk surgical procedures. The recommended minimal hospital volume for PR was set at 11 per year.32,38 Based on our analysis, a clear cutoff volume cannot be defined since there seems to be a continuous trend toward better outcome in higher volumes. Ideally, the mortality data of single institutions should be plotted to determine a true, clinically applicable cutoff value. But a recommendation must be feasible in clinical practice, and the potential benefits should not be outweighed by the impracticalities. Implementation of recommendations always take time, but the Leapfrog Group suggests that 11,200 lives per year could be saved for selected conditions and procedures.38 Surgeons should support the idea that in some high-risk surgical procedures like PR only the patient interest is the leading factor. In some European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany, there are initiatives toward centralization of high-risk surgical procedures, but effects are not noticeable yet.

CONCLUSION

The findings in the present study suggest that the concentration of pancreatic surgery in higher-volume centers is likely to improve outcome. This message has been brought forward in various meetings in The Netherlands of the associations of Surgery, Surgical Oncology, Gastroenterology, and Gastroenterological Surgery. The evaluation showed that the 10-year lasting plea for centralization in these communities did not result in a change in the referral pattern and reduction of the mortality rate after PD. We can conclude that the system of frequent evaluation of the National Registry and reports on various meetings failed to convince surgeons to limit the number of PDs in low-volume centers. Other methods such as interference by the government or health insurance companies have been introduced in some European countries and the United States to change this pattern and to achieve a strong patient driven action toward centralization.7,32 Recently, a first step has been made by the Dutch Government and National Health Council for registration of volume and outcome of high-risk procedures, and this might be necessary to force the Dutch surgical community to centralize.

Discussions

Dr. Ihse: Many thanks for an excellent presentation. I have a comment and 2 short questions to you on this important paper, which tells about the difficulties we may face when we speak out for our patients. My first question is: why do you choose Maradonna? Holland is a football nation with many good football players; why did you not choose Johan Cruyff? Is he, perhaps, a low-volume football player? That was my first question.

As you indicated, there are more than 300 reports in the English language literature which show that patients undergoing various kinds of complex treatment and high-risk surgical procedures had lower mortality rates or otherwise better outcomes if care is provided in centers that have a high case load of patients with the same condition than if care is provided by hospitals with a low case load of such patients. This has been clearly shown for pancreaticoduodenectomy by numerous groups and from many countries. Still, we see no change, especially perhaps in Europe, in referral pattern, as you have demonstrated in a very convincing way in your thorough study. In Sweden, for instance, this operation is still done in 50% of the Swedish hospitals, most of them doing less than 3 operations a year. It is awkward for the surgical profession that the interest of the patients is not given the highest priority. Unfortunately, I must agree with the authors that governmental or other authoritative means are needed to promote the use of high-volume centers for certain types of care. Such means may well be financial in nature. In Stockholm, the County Council, for instance, is paying only for pancreaticoduodenectomies that are done in one of the hospitals, and this is somewhat of a change of course in Sweden. Also, our Board of National Health and Wellfare now is taking sides against low-volume hospitals that persist in performing complex operations. The solution of the problem, though, will finally come, I think, from the increasingly well-informed public who will demand full transparency of the departments’ experience and results before they will lay themselves down on the operation table. This Dutch paper will be helpful in the development and these endeavors. My last question, of course, is: what will be your next step to promote high-volume centers?

Dr. van Heek: The first question refers to soccer, and I should have shown Johan Cruyff; he is indeed the best football player, Maradonna is the second best, and even he needs practicing a lot. Concerning the second question, what would be the next step to realize centralization: we hoped that these findings should help patients to be referred by the doctors to the appropriate (high-volume) hospitals. I agree with you that apparently we failed. So patients should also realize that they should go to high-volume hospitals. Apparently, the patients in The Netherlands are not fully aware that some hospitals have better results than others.

In many other countries, as some areas in the United States, centralization is well accepted since 1990.

Dr. Cameron: Dr. van Heek, this is a very nice ongoing study and very beautifully presented. I am very familiar with Dr. van Heek's contributions to pancreatic diseases: she was the first IHPBA Kenneth Warren Research fellow in pancreatic diseases and spent a year at the Johns Hopkins Hospital a couple of years ago, a very productive year, and I am glad to see you are continuing your interest in pancreatic diseases.

In the middle 1980s in the state of Maryland, a state of 6 million people, the overall mortality in the 45 hospitals for the Whipple procedure was 20%. At that time, the mortality in the Johns Hopkins Hospital was about 2%, but we did less than 20% of the Whipples in the state. By 1994, our market share had increased to over 60% and the mortality in the state dropped from about 20% down to below 5%. That was the first demonstration that I am aware of that regionalization has resulted in the saving of lives for a tertiary care cancer operation. Now why did that occur in Maryland and why hasn't it occurred in The Netherlands? There was no third party payer coercion of sending patients to a high-volume center because in the United States insurance companies are only interested in costs and not in outcome, and they all assumed that community hospitals were cheaper, so it had nothing to do with insurance companies or the government. Medicare and medicate patients can go to any hospital in the States without any steering toward a high-volume center. It happened because it was patient driven, and I agree with Dr. Ingemar Ihse that patient education is what is going to determine centralization and regionalization.

We now do about 85% of the Whipples in the state of Maryland and a significant number of Whipples from surrounding states. We did 270 Whipples last year, and we have done over 250 for the last several years. I think the single most important factor in our instance has been our Web site. We have had a Web site for many years on the Internet, and when someone develops pancreatic cancer, a grandson or granddaughter goes to the Internet and finds our Web site and they get their grandparent, or their father or their mother, to come to Baltimore, and when they arrive, after reading that Web site, they know more about pancreatic cancer than I do. And so it has been entirely patient driven.

I think the emphasis in The Netherlands and elsewhere where regionalization has not taken place should be on informing the public, the patient population, and then it will occur there after. Why hasn't that occurred in The Netherlands? It seems like a small community, with easy access to university centers. Why hasn't this patient driven regionalization occurred in The Netherlands?

Thank you for a very nice presentation.

Dr. van Heek: Thank you Dr. Cameron for your question. We are indeed almost 20 years behind and, of course, I am familiar with the data from the Hopkins Institute.

I think there are several differences. In the United States, patients are used to getting a second opinion and asking for local personal experience of surgeons. In The Netherlands, most patients just go to a surgeon and are operated on without extensive discussion about the experience of their surgeon. The public is not very much informed. Also, publications as the one of Dr. Birkmeyer in Time Magazine, are read by many people in the United States. Patients in the United States are used to visiting Web sites and looking up results from different hospitals.

Another aspect might be that the Dutch, although the country is extremely small, like to stay in a hospital near home. For an American, this is hard to understand, but a drive of 1.5 hours to a hospital is a large distance for patients in The Netherlands.

Dr. Russell: One of the problems of The Netherlands and the United Kingdom is that all the travelers left to the States some years ago, and they all like being the ones that are left like being near home, so we do have a great trouble of getting people to travel. In the United Kingdom, we have taken this over by actually insisting that every patient who has a cancer is discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting between oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons, and the surgeon is there for a lesser voice in that meeting. And if you tell the cancer care nurse that patients should be regionalized, as everyone follows that suit because the patient then is told by the nurse that this is what she is to expect, and this is making a very big difference within the United Kingdom. But being the United Kingdom, alas, the centers are not given the beds to undertake the treatment, and that again is a problem why it is not working yet very well. But the difficulty we still have is what the patients think about it, and really I just wondered if you had asked the patients what they thought about traveling, and how willing they are to travel and why they don't want to travel for treatment; whether you had actually asked the surgeons what their reaction was to these figures, and how many had actually read them and whether they were ignoring them, and I think it is really worth looking into that, and finally what the attitudes of the oncologists are in The Netherlands to regionalization?

Dr. van Heek: Of course, we discussed these results with the colleagues from internal medicine, gastroenterologists, and oncologists, and they all agree that patients should be sent to high-volume centers. However, surgeons from low-volume centers generally mention that the 3 or 4 pancreatic resections they performed the last years went well. Of course, they did not analyze the results of the last 10 years; and according to our data, indeed there would have been a higher mortality.

Dr. Nordlinger: I was very interested in your study outcome looking at the outcome according to the volume, but I think the major issue also, since most of these patients have cancer, is the rate of cure of cancer. It may well be that resection rate, for instance, is not the same with surgeons with more expertise than less expertise. I think it is likely that some tumors are not resected when the surgeons do not have enough expertise, it is likely that some tumors do not get appropriate resection whereas it would be possible. Would you consider looking at these factors as the impact and volume of surgery on cure of cancer?

Dr. van Heek: Do you mean a selection bias of these patients?

Dr. Nordlinger: Impact of volume on cure of cancer survival.

Dr. van Heek: We did not look into it, but there are a few studies reported also showing clearly a positive effect of hospital volume and survival of patients.

Dr. Lerut: We both live in small countries where indeed the health care is very accessible, but the reason that I mostly hear for patients not coming to our institutions is the traffic jams. However, there are several external factors playing a role, the traffic jams are perhaps disguising one of them, ie, the fight for the turf.

Also, your country heavily relies on a medicine driven by general practitioners, and I think they are a key factor why patients are not necessarily sent to the appropriate institutions rather than to a low-volume center. Did you ever make a survey among general practitioners why they send the patients to the low-volume centers, or perhaps are they themselves influenced by their patients to go to low-volume rather than to high-volume centers?

Dr. van Heek: We have not enquired among the GPs, although it is indeed this group that mainly refers patients to hospitals. Unfortunately, generally these patients are not referred with a diagnosis pancreatic carcinoma. The GPs, however, should be well informed now because recently they were informed by the National Health Care Inspection who provided information about the relation of hospital volume and outcome for different diseases.

Dr. Clavien: I would like to congratulate the authors for this important study and make a short comment. The debate on how to improve outcome in specific healthcare systems and culture is fascinating, and often frustrating, as convincingly shown in your longitudinal data gathered in The Netherlands. Volume and experience are obviously paramount for success in performing complex procedures, and there are possibly many ways to achieve this objective. One of them is an individual and direct approach to surgeons and centers performing few cases with questionable results. This approach has been successfully used in Ontario, Canada, where small-volume centers are identified, and contacted by a group of highly credible physicians from Cancer Ontario, such as Dr. Bernard Langer. Facing the actual data, most of these surgeons and centers eventually renounce to these complex procedures. Such strategy, to work, must rely on the ethic of the involved individuals, and also this might be sensed as a gentle initial warning, leading eventually to more stringent actions to direct these patients to larger, specialized centers.

Footnotes

Reprints: D. J. Gouma, MD, Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, Department of Surgery, Meibergdreef 9, PO Box 22660, 1100 DD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: d.j.gouma@amc.uva.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuhlmann KF, de Castro SM, Wesseling JG, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma; actual survival and prognostic factors in 343 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millikan KW, Deziel DJ, Silverstein JC, et al. Prognostic factors associated with resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am Surg. 1999;65:618–623; discussion 623–624. [PubMed]

- 3.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neoptolemos JP, Russell RC, Bramhall S, et al. Low mortality following resection for pancreatic and periampullary tumours in 1026 patients: UK survey of specialist pancreatic units. UK Pancreatic Cancer Group. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1370–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramhall SR, Allum WH, Jones AG, et al. Treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer, and incidence of the disease, in the West Midlands: an epidemiological study. Br J Surg. 1995;82:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1138–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, et al. Surgical volume and quality of care for esophageal resection: do high-volume hospitals have fewer complications? Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan EL, Radzyner M, Rubin D, et al. The influence of hospital and surgeon volume on in-hospital mortality for colectomy, gastrectomy, and lung lobectomy in patients with cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E, et al. Hospital and surgeon procedure volume as predictors of outcome following rectal cancer resection. Ann Surg. 2002;236:583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edge SB, Schmieg RE Jr, Rosenlof LK, Wilhelm MC. Pancreas cancer resection outcome in American University centers in 1989–1990. Cancer. 1993;71:3502–3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. Hospital volume influences outcome in patients undergoing pancreatic resection for cancer. West J Med. 1996;165:294–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperato PJ, Nenner RP, Starr HA, et al. The effects of regionalization on clinical outcomes for a high risk surgical procedure: a study of the Whipple procedure in New York State. Am J Med Qual. 1996;11:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouma DJ, Van Geenen RC, Van Gulik TM, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wade TP, Halaby IA, Stapleton DR, et al. Population-based analysis of treatment of pancreatic cancer and Whipple resection: Department of Defense hospitals, 1989–1994. Surgery. 1996;120:680–685; discussion 686–687. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gordon TA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, et al. Statewide regionalization of pancreaticoduodenectomy and its effect on in-hospital mortality. Ann Surg. 1998;228:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, et al. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery [see comments]. JAMA. 1998;280:1747–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SG, Tosteson AA, et al. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125:250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Gordon TA, et al. Importance of hospital volume in the overall management of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;228:429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon TA, Bowman HM, Bass EB, et al. Complex gastrointestinal surgery: impact of provider experience on clinical and economic outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouma DJ, Obertop H. Centralization of surgery for periampullary malignancy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1361–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simunovic M, To T, Theriault M, et al. Relation between hospital surgical volume and outcome for pancreatic resection for neoplasm in a publicly funded health care system. CMAJ. 1999;160:643–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmann MO, Alderson D, Peters TJ, et al. Influence of specialization on the management and outcome of patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brennan MF. Safety in numbers. Br J Surg. 2004;91:653–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gouma DJ, De Wit LT, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Hospital experience and hospital mortality following partial pancreaticoduodenectomy in The Netherlands [see comments]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 1997;141:1738–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon TA, Burleyson GP, Tielsch JM, et al. The effects of regionalization on cost and outcome for one general high-risk surgical procedure [see comments]. Ann Surg. 1995;221:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA Jr, et al. Variation in postoperative complication rates after high-risk surgery in the United States. Surgery. 2003;134:534–540; discussion 540–541. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Goodney PP, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, et al. Hospital volume, length of stay, and readmission rates in high-risk surgery. Ann Surg. 2003;238:161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho V, Heslin MJ. Effect of hospital volume and experience on in-hospital mortality for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2003;237:509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kingsnorth AN. Major HPB procedures must be undertaken in high volume quaternary centres. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;11:359–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotwall CA, Maxwell JG, Brinker CC, et al. National estimates of mortality rates for radical pancreaticoduodenectomy in 25,000 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbach DR, Bell CM, Austin PC. Differences in operative mortality between high- and low-volume hospitals in Ontario for 5 major surgical procedures: estimating the number of lives potentially saved through regionalization. CMAJ. 2003;168:1409–1414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luft HS, Bunker JP, Enthoven AC. Should operations be regionalized? The empirical relation between surgical volume and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1364–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ihse I. The volume-outcome relationship in cancer surgery: a hard sell. Ann Surg. 2003;238:777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birkmeyer J. Leapfrog Safety Standards: Potential Benefits of Universal Adoption. Washington, DC: Leapfrog Group, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordback L, Parviainen M, Raty S, et al. Resection of the head of the pancreas in Finland: effects of hospital and surgeon on short-term and long-term results. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1454–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg. 2003;138:721–725; discussion 726. [DOI] [PubMed]