Abstract

The incidence of breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the USA exceeds that of other countries. This cannot be explained entirely by the frequency of mammographic screening in the USA and may result from differences in the interpretation of mammograms and/or the frequency with which biopsies are obtained. Although the percentage of DCIS patients treated with mastectomy has decreased, the absolute number is unchanged and the use of lumpectomy with whole-breast radiotherapy has increased in inverse proportion to the decrease in mastectomy. Treatment of DCIS with tamoxifen is still limited.

Introduction

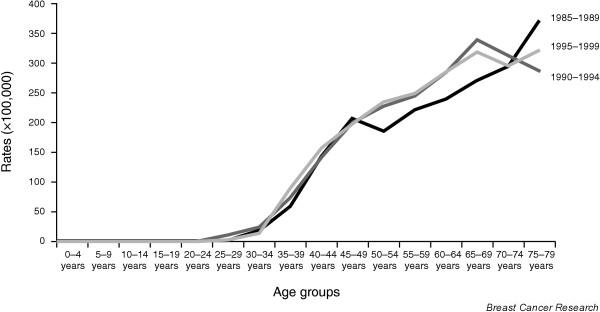

The incidence of breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has increased steadily in all countries as the use of screening mammography has increased [1]. In the USA the incidence of DCIS remained below 5 per 100,000 and DCIS constituted 2.8 to 3.8% of breast cancers diagnosed between 1973 and 1984 [2]. It now exceeds 30 per 100,000 and constitutes 18.6% [3]. During this time the percentage of American women aged 50 years and over who reported having a recent mammogram increased from 27% in 1987 to 69% in 1998 [4]. Cancers detected by screening are more likely to be DCIS, ranging from 18 to 33% in various studies [5].

DCIS with comedo histology is one of the subtypes most likely to recur with an invasive histology [6]. From 1992 to 1999, when the overall incidence of DCIS in the USA increased by 73%, there was no increase in the incidence of comedo histology [7,8]. Several explanations have been suggested for this, the most plausible being that DCIS found in women undergoing screening mammography is more likely to be the non-comedo variety [7].

Although the correlation between increased DCIS with increased use of mammography seems to be universal, the frequency of DCIS is still higher in the USA than in other countries with similar mammography use (Table 1). The incidence of carcinoma in situ (ductal plus lobular) had increased in the USA, England and Switzerland by 1990 [8-10]. However, DCIS incidence in the USA was about thrice that in England and Switzerland. For the early dates, mammography rates might account for the difference in the incidence of DCIS between America and Europe. That is less true today.

Table 1.

Changes in age-adjusted incident rates of DCIS and/or CIS between 1980–2002

| USA [8] | England [9] | Switzerland [10] | ||

| Year | DCISa | CISb | DCISc | CISc |

| 1980 | 4.0 | |||

| 1980–82 | 2.4 | 4.8 | ||

| 1983 | 5.0 | |||

| 1983–85 | 1.8 | 3.6 | ||

| 1984 | 7.8 | |||

| 1986–88 | 3.2 | 5.2 | ||

| 1989–91 | 7.3 | 10.6 | ||

| 1992 | 23.8 | 6.5 | ||

| 1992–94 | 7.9 | 10.4 | ||

| 1995 | 28.8 | 6.8 | ||

| 1998 | 38.0 | 9.4 | ||

| 1999 | 10.5 | |||

| 2001 | 37.8 | 11.6 | ||

| 2002 | 12.0 | |||

aAdjusted to US population in 2000; badjusted to European standard population; cadjusted to population in US 1970 census. CIS, carcinoma in situ; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Mammographic screening in the USA and the UK today

Recommendations for screening in the USA and UK are quite different. In the USA there is no national policy, but most organizations, such as the American Cancer Society, recommend mammograms every 1 or 2 years for women more than 50 years old and many recommend initiating yearly mammograms at the age of 40 years [11]. In the UK, it is national policy to obtain mammograms every 3 years for women aged 50 to 64 years but none for those less than 50 years old [12]. Today the reported rates of mammographic screening in the two countries are similar for women aged 50 to 64 years. According to the 2002 National Health Interview Survey, 78.6% of American women in this age group had a mammogram within the previous 2 years. Similarly, 74.5% of British women aged 53 to 64 years had been screened at least once in the 3 years before 2004 [12]. For women less than 50 years old, 33% of American women received a mammogram in 1998 compared with only 2% in the UK in 2004. After the age of 65 years, the frequency of screening declined abruptly in the UK before 2004, whereas one-third of all mammograms were performed on American women in this age group [12,13]. Although the ratio of DCIS/breast cancer detected by screening mammography is highest in women aged 40 to 49 years, the highest frequency of DCIS per 1,000 mammograms is in the women aged 70 to 84 years [5]. Finally, there may be differences in the socioeconomic status of the screened population in the two countries because mammograms are free in the UK but not in the USA. Thus differences in screening patterns could account for some of the international differences in DCIS incidence.

Mammographic interpretation in the USA versus other countries

There is considerable difference in the interpretation and management of abnormal mammograms in different countries. In a comparison of procedures and outcomes after 1.6 million mammograms in the USA and 3.9 million in the UK between 1996 and 1999, it was found that recall rates per 100 mammograms were 13.4 in the USA versus 7.1 in the UK, open biopsies 1.1 versus 0.7, and open negative biopsies 0.8 versus 0.4. Despite these roughly doubled rates in the USA, there were no differences in the overall cancer detection rate [14]. Perhaps the greater use of open biopsy results in a higher frequency of DCIS because it is often diagnosed incidentally without radiographic findings.

A study that compared variability in mammographic interpretation in 32 reports from community-based screening programs in the USA and eight other countries found that 8.4% of mammograms were judged abnormal in North America versus 5.6% in other countries (P = 0.018) [15]. Abnormal mammograms exceeded 5% in all of the North American programs but in only 10 of the 24 programs elsewhere. DCIS constituted more than 20% of the cancers diagnosed in 4 of the 8 North American programs but in only 4 of the 24 programs elsewhere. There was a significant correlation between the frequency of abnormal mammograms and the percentage of cancers that were DCIS. Factors affecting differences in outcome were the inclusion of younger women with dense breasts, litigation avoidance, and incentives to minimize the number of abnormal mammograms. In the USA, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research suggests that at most 10% of mammograms should be abnormal and 25 to 40% of biopsies should be positive. In the Europe Against Cancer Program the 'acceptable' rate and the 'desirable levels' of abnormal mammograms are less than 7% and less than 5%, respectively, and the corresponding levels for positive biopsies are more than 34% and more than 50%.

Treatment of DCIS

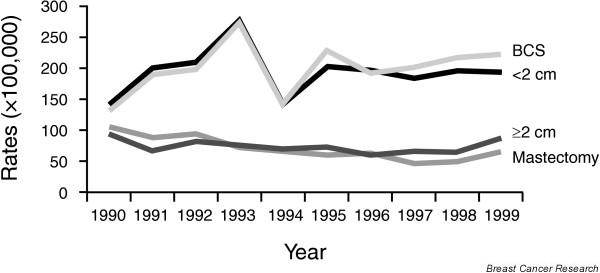

For most of the twentieth century, treatment for DCIS was mastectomy (Fig. 1). Even with the demonstration that lumpectomy and radiotherapy were equally effective for invasive cancer, reluctance to apply this principle to the treatment of DCIS resulted in a very slow decline in mastectomy rates among DCIS patients after 1979. In 2002, 26% of DCIS patients were still treated with mastectomy. During the 1990s, the incidence of DCIS rose while mastectomy rates decreased. As a result the age-adjusted incidence of mastectomy did not change: 7.8 per 100,000 women in 1992 and 1999 [7]. Those most likely to undergo mastectomy were younger patients and those with tumors more than 1 cm in size or with comedo histology [7]. As mastectomy rates have declined, there has been a gradual increase lumpectomy rates to 71% in 2002.

Figure 1.

Treatment of DCIS in the USA, 1973 to 2002. Source: SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results). These data were compiled at the Northern California Cancer Center from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program http://www.seer.cancer.gov SEER*Stat Database: Incidence – SEER 9 Regs Public-Use, Nov 2004 Sub (1973–2002), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2005, based on the November 2004 submission, which is a sum of data from population-based cancer registries at nine distinct geographic sites collected for the period 1 January 1973 to 31 December 2002. The query was limited to women with non-invasive in situ breast cancer, excluding lobular carcinoma in situ. Rates were age-adjusted with US census data from 2000. Patients with any evidence of microinvasive disease would be considered by SEER to have invasive breast cancer and thus were excluded from the study. For this time interval 45,597 cases met this definition, 189 cases in 1973 and 3,335 in 2002. The distribution of patients by type of surgery or use of radiotherapy is based on the patients for whom there is a specific indication that the therapy was given or not given. The denominator for analyses of other therapies is based on the total number of patients diagnosed. The number of patients included in the calculation for 'lumpectomy' includes those who had a single surgical procedure and those who had an initial surgical procedure plus a re-excision. A few patients in the latter category might have been counted twice if the two procedures were performed in different years. XRT, radiotherapy.

In the USA most professional organizations have few, if any, specific recommendations about the management of DCIS, but the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines outlined in Fig. 2 are referred to by many of these groups. Mastectomy is recommended in the presence of diffuse, multifocal DCIS, or when all disease cannot be removed with clear surgical margins after an excisional biopsy. It is likely that many of the 26% of patients treated with mastectomy do not meet these criteria. Axillary lymph node dissection is discouraged unless areas of microinvasion are found on pathology review, and this is reflected in the steady decrease in lymphadenectomy since 1988 (Fig. 1). In 2002 only 11% of patients had a formal node dissection, and 10% had a sentinel node biopsy.

Figure 2.

Recommended management guidelines for DCIS developed by and subscribed to by American breast cancer specialists. The scheme shown here is based primarily on guidelines developed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), a coalition of 19 academic cancer centers in the USA. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, the American Society of Clinical Oncologists, and the American Society for Therapeutic Radiation Oncologists do not at present endorse any specific guidelines for the management of DCIS but refer to those of the NCCN (Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Breast Cancer, V.2.2005: Ductal Carcinoma in Situ, DCIS-1 to 3) in their literature (or where information is provided on the Internet, link to the NCCN site [21]). ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; ER, estrogen receptor; XRT, radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy is recommended for most patients treated with excision, and in practice there has been a steady increase in the use of radiotherapy since the early 1980s. The increased use of radiotherapy antedated the 1993 report from the first randomized trial evaluating radiotherapy for DCIS [16]. In 2002, more than 40% of all patients with DCIS received radiotherapy. The largest cancer registry in the USA, SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) did not link radiotherapy to a specific surgical procedure, but it is likely that most of the patients given radiotherapy had lumpectomy rather than mastectomy. From this we estimate that 64% of patients treated with lumpectomy also had radiotherapy.

Excision without radiotherapy is offered to patients with small tumors and low-grade, non-comedo histology, but it is not formally 'recommended' in the NCCN criteria, which define 'small' as '0.5 cm or less'. Some American DCIS specialists feel comfortable using excision alone with lesions 2.5 cm in size or smaller regardless of tumor grade if the margins are more than 10 mm [17]. In practice, about 36% of patients with DCIS seem to be treated with lumpectomy alone (Fig. 1). Excision alone without radiotherapy is more likely to be employed for those aged more than 50 years [7].

In a survey, North America radiotherapists (n = 1,137) were more likely than European radiotherapists (n = 702) to recommend radiotherapy for DCIS, but the differences were greater among community than academic radiotherapists [18]. For example, when asked about treatment of a grade I to II, less than 2.5 cm DCIS lesion with a margin more than 10 mm, 53% of the academic and 28% of the community radiotherapists in North American indicated that they would not use radiotherapy, whereas 55% of the academic and 60% of the community radiotherapists in Europe recommended no radiotherapy for this lesion.

Although the first randomized clinical trial that demonstrated a beneficial effect from tamoxifen for DCIS appeared in 1999 [19], there is still considerable reluctance to employ this treatment routinely. The NCCN recommends that physicians 'consider' tamoxifen for DCIS regardless of the primary treatment or tumor characteristics (Fig. 2). There are no data available from SEER on the use of tamoxifen for DCIS, but its use in this setting has been reported from several cancer centers. In a retrospective evaluation of 277 DCIS patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1999 and 2002, 60% were offered tamoxifen; 54% of those offered accepted the recommendation [20]. There was no change in the frequency with which tamoxifen was offered between 1999 and 2002. The most common reason that physicians did not recommend tamoxifen was that the patient's primary treatment was mastectomy. The most common reason that patients declined tamoxifen was fear of the side effects. Of those given tamoxifen, 21% discontinued the medication because of side effects or complications. Thus, only 27% of this sample completed a 5-year course of tamoxifen when it was offered.

In the international survey of radiotherapists described above, North Americans were more likely to recommend tamoxifen as well as radiotherapy [18]. For example, 74% of academic and 76% of community-based radiotherapists in North America recommended tamoxifen for a DCIS of less than 2.5 cm with grade 3 histology and margins of 1 to 3 mm compared with 39% of academic 49% of community-based radiotherapists in Europe who made this recommendation. On both sides of the Atlantic, radiotherapists were more likely to recommend tamoxifen for tumors of higher grade or narrower margins.

Is DCIS overdiagnosed and overtreated in the USA?

DCIS is diagnosed more frequently and treated more aggressively in the USA than elsewhere. It is plausible that differences in the incidence of DCIS in countries where routine screening mammography is well established are related as much to frequency of biopsies for suspicious lesions as to the frequency of mammography.

The question of whether DCIS is diagnosed too frequently or treated too aggressively in America depends on whether these practices result in better outcomes. The outcome of greatest interest, of course, is breast cancer mortality, but because the reported incidence of death from breast cancer in patients diagnosed with DCIS is somewhat less than 2%, it will be difficult to detect differences between large populations in which there are multiple variables in addition to the method of diagnosis and treatment that might account for any observed small differences. This problem is evident in the comparison of mortality in patients diagnosed with DCIS during two periods in the USA [2]. Among women in SEER who were diagnosed with DCIS from 1978 to 1983, mortality from breast cancer was 1.5 at 5 years and 3.4 at 10 years. For the interval 1984 to 1989 these rates were 0.7 and 1.9, respectively. In the later period, the use of mammography increased rapidly and mastectomy for DCIS decreased. Was mammography improving the prognosis of patients with DCIS because of 'earlier' detection, or were more cases of DCIS with low malignant potential being diagnosed, thus exaggerating the apparent survival benefit? This cannot be determined. On a more positive note, outcomes that affect quality of life, such as the use of breast-conserving surgery without axillary lymph node dissection, are clearly improving.

Conclusion

Although one might conclude that the aggressiveness of treatment decreased in the 1980s in the USA as a result of decreased mastectomy rates, the opposite can be said of the period after 1991, first with increasing use of radiotherapy and now tamoxifen. There is reason to believe that physicians are becoming more selective in their use of therapies. Comedo DCIS has remained relatively constant in the face of an overall increase in DCIS, and as of 1999, 33% of patients with comedo carcinomas did not receive radiotherapy [7]. However, the survey of radiotherapists suggests that, at least among American academic physicians, radiotherapy is limited more and more to this group of patients [18]. Tamoxifen for DCIS has not been as widely and quickly embraced as radiotherapy was a decade ago. It is plausible that as more information is generated on the natural history of DCIS, practice patterns in the USA will once again change. It is less certain that the incidence of DCIS will decrease.

Abbreviations

DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Competing interests

ICH has received reimbursements, fees, funding or salary from AstraZeneca in the past five years.

Note

This article is part of a review series on Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer, edited by Nick E Day, Stephen Duffy and Eugenio Paci.

Other articles in the series can be found online at http://breast-cancer-research.com/articles/review-series.asp?series=BCR_Overdiagnosis

References

- Recht A, Rutgers EJ, Fentiman IS, Kurtz JM, Mansel RE, Sloane JP. The fourth EORTC DCIS Consensus meeting (Chateau Marquette, Heemskerk, The Netherlands, 23–24 January 1998) – conference report. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernster VL, Barclay J, Kerlikowske K, Wilkie H, Ballard-Barbash R. Mortality among women with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the population-based surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:953–958. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Mariotto A, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK, (eds) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/, based on November 2004 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer. Nass SJ, Henderson IC, Lashof JC, (eds) Mammography and Beyond: Developing Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer. National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, Division of Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council: Washington DC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ernster VL, Ballard-Barbash R, Barlow WE, Zheng Y, Weaver DL, Cutter G, Yankaskas BC, Rosenberg R, Carney PA, Kerlikowske K, et al. Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ in women undergoing screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1546–1554. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ER, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, Costantino J, Fisher B, Paik S, Wolmark N. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:429–438. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990801)86:3<429::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter NN, Virnig BA, Durham SB, Tuttle TM. Trends in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:443–448. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CI, Daling JR, Malone KE. Age-specific incidence rates of in situ breast carcinomas by histologic type, 1980 to 2001. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1008–1011. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N, Gautrey M, Quinn M. Cancer Trends in England and Wales, Incidence Data to 2002. National Cancer Intelligence Centre, Office for National Statistics; 2005. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/Expodata/Spreadsheets/D8981.xls [Google Scholar]

- Levi F, Te VC, Randimbison L, La Vecchia C. Trends of in situ carcinoma of the breast in Vaud, Switzerland. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:903–906. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for breast cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:344–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_1-200209030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast Screening Programme, England: 2003–2004 http://www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Statistics/StatisticalWorkAreas/StatisticalHealthCare/StatisticalHealthCareArticle/fs/en?CONTENT_ID=4104034&chk=mjJ%2Bof

- Center for Disease Control . National Center for Health Statistics, United States; 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bindman R, Chu PW, Miglioretti DL, Sickles EA, Blanks R, Ballard-Barbash R, Bobo JK, Lee NC, Wallis MG, Patnick J, et al. Comparison of screening mammography in the United States and the United Kingdom. JAMA. 2003;290:2129–2137. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore JG, Nakano CY, Koepsell TD, Desnick LM, D'Orsi CJ, Ransohoff DF. International variation in screening mammography interpretations in community-based programs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1384–1393. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Costantino J, Redmond C, Fisher E, Margolese R, Dimitrov N, Wolmark N, Wickerham L, Deutsch M, Ore L, et al. Lumpectomy compared with lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer. N Eng J Med. 1993;328:1581–1586. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306033282201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Groshen S, Waisman JR, Lewinsky BS, Martino S, Gamagami P, Colburn WJ. The influence of margin width on local control of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med . 1999;340:1455–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceilley E, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, Kachnic L, Powell S, Taghian A. The management of ductal carcinoma in situ in North America and Europe. Results of a survey. Cancer. 2004;101:1958–1967. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, Wickerham DL, Fisher ER, Mamounas E, Smith R, Begovic M, Dimitrov NV, Margolese RG, et al. Tamoxifen in treatment of intraductal breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-24 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1993–2000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TW, Hunt KK, Mirza NQ, Thomas ES, Singletary SE, Babiera GV, Meric-Bernstam F, Buchholz TA, Feig BW, Ross MI, et al. Physician recommendations regarding tamoxifen and patient utilization of tamoxifen after surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 2004;100:942–949. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology – v.2.2005 – Breast Cancer http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf