Abstract

This paper describes the new outcomes-based curriculum at the University of Miami School of Medicine, a model curriculum for the first decade of the twenty-first century. The new curriculum has a strong emphasis on evidence-based medicine (EBM), implemented throughout its four years as a component of one of its longitudinal themes. The “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component, which begins at orientation, was developed and is implemented by the Louis Calder Memorial Library, the center of EBM focus and activity for the curriculum and other initiatives at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center. The authors are unaware of any published reports of library-centric EBM initiatives as part of a longitudinal theme of a four-year outcomes-based curriculum. Other innovations of the EBM component in the new curriculum to date include use of BlackboardTM and CATmakerTM software programs for self-paced, interactive educational opportunities.

INTRODUCTION

The University of Miami School of Medicine began in 1952 as the State of Florida's first accredited medical school, with the then-traditional didactic lecture curriculum. Although at many schools medical school curricula have gradually evolved—from the original didactic lecture curriculum to the student-centered curriculum of the 1970s, to the problem-based learning curriculum of the 1980s, to the relevance curriculum of the 1990s, and then to the outcomes-based curriculum of the current decade [1–5]—the University of Miami underwent no major curriculumwide reform during the past fifty years. During the summer of 2001, the School of Medicine underwent a sea change—a revolution, not an evolution—when it leapfrogged from the original didactic lecture curriculum to an outcomes-based curriculum with a strong emphasis on evidence-based medicine (EBM).

EBM has been defined as “formulating clinical questions, retrieving and evaluating the evidence from the literature, and applying the obtained information to the clinical problem at hand” [6] or the “pragmatic process of using the literature to benefit individual patients while simultaneously expanding the clinician's knowledge base,” which, when incorporated properly, becomes “a powerful educational tool and a model for lifelong learning” [7]. The Louis Calder Memorial Library of the University of Miami School of Medicine was given the opportunity in 2000 to develop and implement the “Evidence-Based Medicine and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of one of the longitudinal themes of the new curriculum. This paper describes the new curriculum at the School of Medicine, the unique “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component developed by the library and taught by library staff during year 1, related EBM and medical informatics initiatives developed and implemented for faculty development, and emerging new EBM initiatives for accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and for continuing medical education (CME).

NEW OUTCOMES-BASED CURRICULUM

Goals, learning objectives, and assessment.

The identification of outcomes, the development of a curriculum to teach the identified outcomes, and the creation of assessment strategies to ensure that students master the specified outcomes by graduation, while asserting that all students can succeed, are the hallmarks of the outcomes-based curriculum model adopted in Miami. The curriculum is not only focused on ensuring that students master the outcomes, it is derived from the outcomes students need to demonstrate, rather than from objectives written for an existing curriculum. Curriculum decisions are driven by the outcomes students should possess. Learning outcomes are identified and communicated to all. The identified learning outcomes include: communications skills, clinical skills (diagnosis, management, and prevention), problem-solving skills, use of basic science in the practice of medicine, moral reasoning and clinical ethics, social and community context of health care, self-awareness, self-care and personal growth, and lifelong learning skills.

Assessment of student progress, which is key to curriculum reform, involves knowing, knowing how, showing how, and doing. “Knowing” is a test of knowledge, assessed with multiple choice questions, self-assessment questionnaires, and other methodologies. “Knowing how” is a clinical-based test, assessed with practicals, essays, patient management problems, and orals. “Showing how” is a test of performance, assessed by observation, standardized patients, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), and so on. “Doing” is a test of practice, assessed with real patients, videos, logs and portfolios, and stealth points. Major issues of all assessment methodologies include students being given appropriate feedback in a timely manner; opportunities to demonstrate competency; opportunities for improvement and remediation, if necessary; and then additional opportunities to demonstrate competency.

Components and governance.

During the first two years, the outcomes-based curriculum consists of four major components. The “Core Principles of Basic Sciences” component comprises the first semester of year 1, nineteen weeks during which students are introduced to the fundamental principles and vocabulary for each of the sciences basic to the practice of medicine. The basic sciences disciplines are presented in the following four groups: (1) developmental and molecular genetics, embryology, and cellular biology; (2) human body histology, gross anatomy, and embryology; (3) cellular physiology and metabolism, including biochemistry; and (4) host defenses and pharmacological responses, including immunology, pathology, pharmacology, and microbiology.

The eight “Integrated Organ System Modules” span the second semester of year 1, the first semester of year 2, and the first part of the second semester of year 2, for a total of forty-nine weeks. These modules feature integrated teaching of basic molecular, cellular, and organ systems processes along with the mechanism of disease. Following a brief review of anatomy, students progress through the physiology to the pathophysiology, radiology, pathology, and pharmacology of disorders of each organ system. They begin with the neurological and behavioral sciences, followed by the cardiovascular system, respiratory system, renal and urinary systems, endocrine and reproductive systems, gastrointestinal system and nutrition, hematology and oncology, and musculoskeletal and skin systems. The learning methodologies include significant time in group discussion, demonstrations, workshops, and self-study, with limits on the number of lecture hours in any week.

The “Problem-Based Learning Block” ten-week module in the second part of the second semester of year 2 emphasizes problem-solving skills for lifelong learning, concludes the second year, and serves as a transition into the clinical rotations. Students will have two hours of lecture time and nine hours of tutorial time scheduled each week during this PBL block. During years 3 and 4, students will complete fifty-four weeks of ten required core clinical clerkships and twenty-eight weeks of ward subinternship selectives and electives. Although the traditional boundary between the third and fourth years does not exist, required clerkships must be completed during the first semester of year 4.

Knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are identified as core competencies, but which are not effectively confined to one course, are grouped into seven longitudinal themes. The interdisciplinary longitudinal themes are coordinated with other components throughout the four-year curriculum. They rely heavily on active, adult learning methodologies and use a competency-based approach to learning and evaluation. As is evident from Table 1, longitudinal theme III is “Population Medicine and Evidence-Based Practice.” The library's “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component is part of theme III.

Table 1 Seven longitudinal themes

One or more faculty members are designated as the course coordinator or coordinators for each basic science discipline and major component of the longitudinal themes to coordinate the efforts of the large number of participating faculty. A module team of clinical and basic science faculty, headed by a module director, manages the eight integrated organ system modules. The course coordinators and module directors interact with Medical Education Administration for the implementation and operation of the curriculum. They comprise the Curriculum Advisory Committee, along with representation from the School Council, department chairs, and student body. This committee meets monthly and is advisory to the Executive Curriculum Committee, which, together with Medical Education Administration, forms the strong, central, school-centered authority that directs and manages the curriculum. The authority for curriculum decision making rests with the Executive Curriculum Committee, comprised of faculty appointed to a three-year tenure and paid for this effort.

“EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE (EBM) AND USE OF THE BIOMEDICAL LITERATURE” COMPONENT

Governance, goals, and learning opportunities.

In preparation for the new curriculum, which began in August 2001, the library's infrastructure was significantly changed and enhanced. The previous Education Department and Reference and Information Services Department were merged in June 2000, both physically and administratively, creating the new Reference and Education Services Department. The director for education position was redefined as the coordinator for health informatics education, and the director for reference position was expanded to include education. An administrative/professional position in the Reference and Education Services Department was redefined as a systems specialist for information support, and a new reference and education faculty position was created. By August 2001, the Reference and Education Services Department consisted of five faculty positions. An office and small classroom for the coordinator for health informatics education was created from an existing reference faculty office adjacent to the main reference and education services desk.

The first meeting of the longitudinal theme III “Population Medicine and Evidence-Based Practice” course coordinators and related faculty, scheduled by Medical Education Administration, was held in November 2000. Coordinators of each of the three theme III components (EBM, medical informatics, and epidemiology/public health) developed a document with the knowledge and skills identified for their components, the goals and teaching and learning opportunities planned for the knowledge and skills, and the curriculum time required for implementation. The knowledge and skills and the goals identified for the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component were based on four nationally recognized standards [8–11] and grouped into three broad sections. The introduction included basic information on the biomedical literature and the ways to access it, as well as basic information on EBM and the ways to actually practice it. The “EBM Search Strategies” section included formulating relevant and answerable questions and developing search strategies to answer the questions. The third section, “Select and Manage Appropriate Evidence,” included retrieving full-text articles and assessing the validity of the evidence in the articles.

The goal was to support the five primary roles future physicians assume as identified in the Association of American Medical Colleges' (AAMC's) Medical Informatics Objectives [12]: lifelong learner, clinician, educator or communicator, researcher, and manager. The teaching and learning opportunities identified were based on strategies espoused for the new curriculum, existing opportunities for the orientation session and MEDLINE instruction in place since 1985 [13, 14], and opportunities and strategies in place at other professional schools in the university. Opportunities included lecture, video, and live demonstrations; self-paced tours and assignments in the Blackboard 5: Learning SystemTM course management software from Blackboard in Washington, DC; hands-on search assignments using small group or one-on-one instruction; and generation and presentation of critically appraised topics (CATs). In December 2000, the required document for the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component was submitted to Medical Education Administration for approval.

In January 2001, an EBM team was created consisting of the coordinator for health informatics education, the director for reference and education services, the systems specialist, and the deputy director. The team met weekly from February through July to develop the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component. A variety of lecture, small group, and self-paced, interactive educational opportunities were developed for students to acquire the knowledge and skills identified. The adequacy of the library's EBM resources was assessed and addressed by the acquisition of additional EBM electronic resources, such as the Clinical Evidence database produced by the BMJ Publishing Group. The EBM teaching and learning opportunities, which began at the outset of the new curriculum, were coordinated with the assignments and tests of the rest of the curriculum to avoid conflicts whenever possible.

Components and curriculum coordination, year 1.

Orientation

The “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of longitudinal theme III begins during freshman orientation with a two-hour large group session. The senior associate dean for medical education gives an informative and highly motivational talk on the importance of EBM and lifelong learning. A newly revised version of a fifteen-minute videotape used in previous years, titled The Anatomy of Biomedical Information, is then shown. The tape is followed by a live fifteen-minute demonstration of the library's Website, during which the director for reference and education services emphasizes the online catalog, MD Consult, electronic journals, and the library's Internet catalog of resources in the health sciences. The demonstration concludes with a handout on the library's hours, collections, and services. The handout includes information on the required library-orientation, walking, audiotape tour and concludes with instructions on accessing electronic resources remotely through the proxy server and logging into the university's Blackboard site to complete the first six learning opportunities of the semester.

The coordinator for health informatics education concludes the two-hour large group session by distributing the course syllabus and presenting an overview of the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” curriculum for years 1 and 2. The coordinator then focuses on the six Blackboard assignments that must be completed before the small-group, hands-on MEDLINE search training sessions, which begin the following month. The first Blackboard assignment reviews the electronic resources on the library's Website demonstrated in the session and includes clips from the videotape shown during the large group session. The five additional Blackboard assignments introduce students to the principles and vocabulary of EBM and MEDLINE searching they need to be familiar with to maximize their MEDLINE training sessions. The coordinator for health informatics education's PowerPoint presentation consists of highlights from the PowerPoint presentations that form the basis of the five Blackboard assignments.

Core principles of basic sciences

The “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of longitudinal theme III begins in the “Core Principles of Basic Sciences” component of the curriculum with the six Blackboard assignments. The five EBM learning opportunities are:

Introduction to Evidence Based Medicine: the development and spread of EBM, the five steps of practicing EBM and its benefits and limitations

Asking Answerable Clinical Questions: the types of clinical questions, how to identify areas of knowledge gap pertaining to a clinical situation and to formulate well-built questions based on patient or problem, intervention, comparative intervention, and outcome (PICO) and the advantages of well-formulated questions

Specific EBM Questions for Diagnosis, Therapy, Etiology or Harm, and Prognosis: the key questions that assess the validity of the evidence in a study and the ways to answer them

How to Search for the Current Best Evidence: sources to search, including texts, EBM resources, and Internet resources and the basic principles of searching MEDLINE: Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Boolean operators, limits, textword searching, links to full text, reformulation of strategies for another database, modification, and saving strategies for future patient encounters

Filtering a Literature Search for EBM: hedges prepared for therapy, diagnosis, etiology or harm, and prognosis

Each Blackboard presentation consists of approximately fifty slides, based wholly, or for the most part, on the second edition of Sackett's Evidence-Based Medicine; How to Practice and Teach EBM [15]. Each has ten multiple choice questions, based on the knowledge and skills presented in the slides. Because the Sackett text is required—the slides are accessible on the password protected server in Medical Education Administration, and print copies of the slides are made readily accessible to the students—the quizzes can be open-book if the student chooses. The Blackboard software grades each quiz and provides detailed information on the days, times of the day, and total time spent by all students on these assignments.

Following the Blackboard assignments, students attend a two-hour, hands-on, small-group MEDLINE tutorial in the library's electronic classroom, during which library faculty demonstrate the EBM search process. The instructor identifies a knowledge gap based on a clinical situation and formulates a question with the PICO elements. The instructor then creates a search strategy that is executed and filtered with an EBM hedge. An article is identified and procured, and the instructor discusses how to prepare a written summary on what was learned and on any problems encountered to be used for self-evaluation of performance while practicing EBM. Students are then assigned a knowledge gap/PICO question MEDLINE search that they must perform and then present in a follow-up one-hour small-group session several weeks later. Library faculty are readily available to assist with these searches when necessary. A third EBM MEDLINE search is then assigned, which students perform and submit for grading by the middle of the semester. The fourth and fifth EBM MEDLINE searches of the “Core Principles of Basic Sciences” component are assigned by the clinical skills coordinator later in the semester (longitudinal theme IV). Students are required to submit a formulated knowledge gap question based on an actual patient, the search strategy performed, and a copy of the article retrieved and selected. All searches are also graded by library faculty.

Organ system modules

During the first three months of the second semester of year 1, as a component of the first organ system module (neurological and behavioral sciences), students complete four more Blackboard assignments on asking an answerable question relevant to a study type (diagnosis, therapy, etiology or harm, and prognosis) and creating a critically appraised topic (CAT) [16, 17] using the CATmakerTM (student version 1.0s) software from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in Oxford, England:

Creating a CAT—diagnosis: blind comparison with “gold” standard, appropriate patient spectrum, sensitivity and specificity, likelihood ratio, pre- and posttest probability, etc., and CATmaker for diagnosis

Creating a CAT—therapy: randomized assignment of patients, type of follow-up, analysis of patient groups, blinded treatment, relative risk reduction, absolute risk reduction, number needed to treat, number needed to harm, etc., and CATmaker for therapy

Creating a CAT—etiology or harm: cohorts defined and similar in all ways other than exposure, objective outcome assessment, type of follow-up, patient expected event rate, etc., and CATmaker for etiology

Creating a CAT—prognosis: patient sample assembled at common, early point in disease progression, type of follow-up, blind outcome criteria, confidence interval, etc., and CATmaker for prognosis

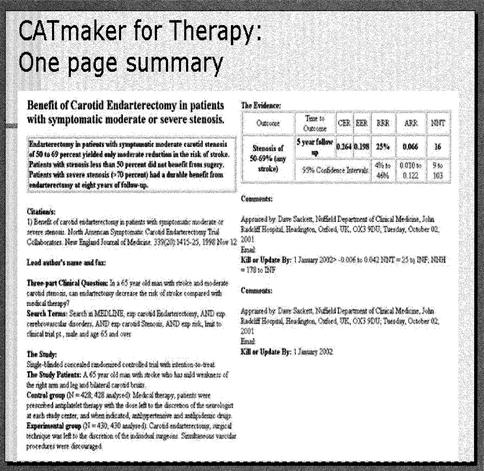

Each of the four assignments presents students with a clinical scenario, for which an answerable question is formulated, an EBM MEDLINE search is performed, an article is selected and subjected to a series of questions to determine the validity of the evidence it contains, and the CATmaker software program is used to create a critically appraised topic. Each CAT includes the knowledge gap question; the clinical bottom line or recommendation regarding diagnosis, treatment, etiology, or prognosis; the selected citation or citations; the search terms used; the clinical scenario; information on the study; the evidence; and comments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Critically appraised topic (CAT) using Catmaker software

During the “Cardiovascular Organ Module,” in the second half of the second semester of year 1, the class is divided into four groups for each of two four-hour EBM group sessions. During the first EBM session, library faculty demonstrate to each of the four groups the process for creating a CAT on a cardiovascular topic with which students are familiar. Each group is assigned a clinical scenario on a cardiovascular disease process, taught during the organ system module, approved by the module coordinator, and searched by library faculty to ensure that at least one article with valid evidence is available. Each group is subdivided into four small groups, of about nine students each and assigned the task of creating a CAT on the EBM aspect of the clinical scenario assigned to the group: diagnosis, therapy, etiology or harm, or prognosis.

During the second four-hour EBM group session about one month later, each of the small groups presents a CAT on their aspect of the cardiovascular scenario to the rest of the students in the group. To prepare for the CAT presentation, each student reads the clinical scenario assigned to the group, formulates a knowledge gap question, does an EBM MEDLINE search, selects the best article, and critically appraises the evidence in the selected article for validity and importance. The small groups meet individually to agree on the one best article from the articles selected by each student. Each group then generates a one-page CAT using the CATmaker software. At the second group session, each small group presents their CAT, and each student submits the search he or she performed.

Assessment and evaluation.

Competencies in the longitudinal themes are graded as pass or fail at the end of each of the first two years. The “grade” is based on points given throughout the first two years for the tasks and assignments completed by each student. During year 1, points are given for completing the audiotape tour, the ten Blackboard quizzes, the five MEDLINE searches, the presented and submitted CATs, and remediation when needed. Points accumulated by each student are entered into Blackboard and can be viewed by students when they log in to the software. To pass, students must earn at least 70% of the maximum number of points that can be accumulated. If they do not pass, they are given opportunities to remediate and demonstrate competency following the remediation. The assignments are also categorized because a portfolio is created and maintained for each student by Medical Education Administration and includes the following broad competencies: lifelong leaning/problem solving (L/P), communication (C), or use of the basic sciences (B). During year 2, six additional CATs are prepared for six different organ modules and four additional EBM MEDLINE searches are performed by each student for longitudinal theme IV “Clinical Skills.”

During the first year, the criteria for grading the EBM literature search assignments are the required use of an EBM hedge and the proper use of the following four search elements: explosion of proper MeSH terms, focusing of proper MeSH terms, proper use of subheadings, and effective use of Boolean operators. If all four elements are present in the submitted search strategy, the search is given the maximum number of points, with fewer points assigned for only two or three of the elements. If the search does not meet at least two of the four elements, no points are assigned and remediation is indicated. If the student meets with library faculty for remediation, the lowest number of points are assigned. Library faculty compare the article selected from the search retrieval with the information sought in the submitted knowledge gap question and give written comments and suggestions that are returned to the student in a timely manner. These objective criteria appear in the course syllabus and have met with good initial student satisfaction.

Criteria for evaluating the CAT presentations and submissions are: (1) appropriateness of the knowledge gap question with respect to the assigned clinical scenario, (2) thoroughness and effectiveness of the EBM MEDLINE search, (3) CAT one-page summary, (4) small-group presentation, and (5) individual contribution to the group as reviewed by peers. The primary evaluation methodology for the CAT assignments is peer evaluation. Each student completes a peer evaluation form for each CAT presented and a second peer evaluation on the individual contribution of each student in his or her group.

Faculty and the course components are formally evaluated by the students using an instrument designed and implemented by Medical Education Administration. The results of the evaluation are also analyzed and communicated by Medical Education Administration to the faculty member, the department chair, and the dean. Courses are also evaluated by their coordinators, in conjunction with all teaching faculty, and then by teams of coordinators for the Curriculum Advisory Committee. Student evaluations of the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component taught during fall 2001 were generally favorable and contained suggestions for improvement, many of which have been addressed for the new academic year. More than 70% thought the course overview was communicated effectively with clear goals and objectives and that the instructor was willing and available to work with students to meet their needs. Seventy five percent liked the hands-on experiences in small groups and the MEDLINE search assignments, but only 30% liked the Blackboard quizzes or the audiotape tour of the library. The students recognized the importance of EBM in their future practice and found the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component helpful in gaining very important skills.

Students are individually evaluated by Medical Education Administration at the end of each year in an exit interview, in which a mentor reviews the student's portfolio. Based on this evaluation, the students progress to the next level or are required to perform some remediation and reassessment prior to progressing. At the end of year 1, students also participate in a week-long evaluation period to assess whether or not they have achieved certain competencies. This evaluation is a clinical-based test of the “knowing how” assessment strategy of the outcomes-based curriculum.

For the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component, students are assigned one of five clinical scenarios or patient management problems for which they do a long report. All scenarios involve disease states taught during year 1. The report begins with the initial hypothesis, a list of the patient's problems, and the known and unknown elements based on the clinical scenario. Students then identify the learning issue and the references used to fill the knowledge gap. A required source is a MEDLINE search, for which students include the strategy used and the article selected from the retrieval, together with the abstract. The report concludes with the student's plan to manage the patient. The criteria used to evaluate the EBM search assignments during year 1 are used by library faculty to evaluate the knowledge gap question, search strategy, and article selected to answer the question. Preliminary evaluation of the EBM competencies of the reports submitted by students indicate a high level at the “basic” competency level expected of students at the end of year 1. The clinical portions of the report are evaluated by Medical Education Administration.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Overall, Medical Education Administration, the library, and the students are very satisfied with the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of year 1 of longitudinal theme III of the outcomes-based curriculum at the University of Miami School of Medicine. Based on the course evaluations, the concentration of curriculum time during the first semester “Core Principles of Biomedical Sciences” component is appropriate for the students' introduction to the core principles and vocabulary of EBM and EBM literature searching. The development of Web-based, self-paced, interactive assignments, using Blackboard, on EBM and EBM searching by library faculty, based on nationally recognized EBM resources written by clinicians, is recommended as an appropriate, effective instructional format for library faculty teaching of EBM. The completion of the Blackboard assignments prior to the hands-on, small-group MEDLINE training sessions is recommended, based on the high rating received by the MEDLINE sessions on the objective student course evaluation administered by Medical Education Administration. Although some students criticized the Blackboard assignments, their criticism was based primarily on the scheduling of these assignments in the curriculum, and not the instructional format, which was favored over didactic lectures.

Students begin applying their EBM knowledge and searching skills to actual patients in the “Clinical Skills” component taught by clinicians by the end of the first semester, with the library continuing to assist with and grade student searches during the entire curriculum. This approach is believed to be innovative and consistent with the new outcomes-based curriculum. Although a four-year integrated program for EBM instruction, with library faculty teaching EBM searching, is in place at one other medical school [18], the application of EBM to patient care does not begin until the third year. The integration of EBM during the third-year clerkships has been well documented since 1997 [19], and there are increasing numbers of EBM senior year electives [20].

The principles of EBM are reinforced, and analysis of the literature is taught by epidemiologists in the epidemiology component of longitudinal theme III at the beginning of the second semester of year 1, about the same time analysis of the evidence is introduced by library faculty with Blackboard assignments based on nationally recognized sources and the use of CATs. The CATmaker software, used by students during the second organ system module to develop a CAT in small groups, provides opportunities for interactive learning and peer student evaluations, methodologies embraced by the outcomes-based curriculum. Critical analysis of the literature is reinforced by clinical and basic science faculty throughout the entire curriculum.

A primary reason for the appropriateness of the library faculty introducing EBM and EBM searching, other than their knowledge of and skills with searching, is their knowledge of and skills with EBM and EBM sources, acquired beginning in 1997, and the general lack of EBM knowledge and skills on the part of the school's teaching faculty. A challenge, for example, in shifting the students to the “Clinical Skills” component during the first year was the coordinator's lack of familiarity with the vocabulary of identifying knowledge gaps and formulating answerable questions based on PICO. Similarly, a challenge in the second semester was incorporating the CAT assignments into the organ system modules. Because the senior associate dean for medical education was aware of the EBM situation on campus, the library was not only the appropriate, but perhaps the sole department, to teach EBM other than Medical Education Administration.

During the years prior to 2001 as the new curriculum was being planned, developed, and communicated to the teaching faculty, several departments recognized that many of their teaching faculty lacked the necessary EBM knowledge and medical informatics skills. The first department to recognize this need was psychiatry and behavioral sciences, which is headed by a world-renowned chair who had just served as chair of the highly successful Dean's Task Force on the Library. This department also boasted one of only two departmental librarians on the medical center campus. This chair turned to the library to meet this need. Had the faculty's need for EBM been addressed in other ways—such as the development of an EBM working group of faculty, administrators, and librarians or the formal training in EBM by faculty at schools such as McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, with a long tradition of EBM training and innovation [21]—the development and implementation of the introductory EBM component might not have involved the library.

In response, a medical informatics/EBM course was developed and implemented by the library for the teaching faculty in this department [22]. The departmental librarian, who also participated in the teaching, coordinated the course with the teaching faculty's existing competencies and their schedules. The course focused on four core competencies: computer literacy, communications, information management, and computer-aided learning. The course and model have since been modified and implemented for teaching faculty in other departments upon request. An “EBM Literature Searching Workshop” was also developed upon request from clinical providers to be given to faculty and clinical supervisors. It is anticipated that these initiatives, together with the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of the undergraduate medical education curriculum, will be adapted beginning in July 2002 to meet the evidence requirements of the new general competencies of the ACGME Outcome Project, approved and scheduled for implementation in July 2002 [23], and the new EBM requirements of AAMC for accredited CME providers [24]. That the initiatives meet the evidence requirements of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) was confirmed during the 2002 site visit, during which the “EBM and Use of the Biomedical Literature” component of the new outcomes-based curriculum was featured by Medical Education Administration.

Contributor Information

Suzetta Burrows, Email: sburrows@med.miami.edu.

Kelly Moore, Email: Kmoore@med.miami.edu.

Joaquin Arriaga, Email: Jarriaga@med.miami.edu.

Gediminas Paulaitis, Email: Gpaulaitis@med.miami.edu.

Henry L. Lemkau, Jr., Email: hlemkau@med.miami.edu.

REFERENCES

- Harden RM, Crosby JR, and Davis MH. AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 1. an introduction to outcome-based education. Med Teach. 1999 Jan; 21(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Dollase R. AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 2. planning, implementing and evaluating a competency-based curriculum. Med Teach. 1999 Jan; 21(1):15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David MF, Friedman M. AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 3. assessment in outcome-based education. Med Teach. 1999 Jan; 21(1):23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross N, Davies D. AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 4. outcome-based learning and electronic curriculum at Birmingham Medical School. Med Teach. 1999 Jan; 21(1):26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden RM, Crosby JR, Davis MH, and Friedman M. AMEE guide no. 14: outcome-based education: part 5. from competency to meta-competency: a model for the specification of learning outcomes. Med Teach. 1999 Nov; 21(6):546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SH, Kaiser S, Morgan LK, Sullivan J, Siu A, Rose D, Rico M, Smith L, Schechter C, Miller M, and Stagnaro-Green A. An integrated program for evidence-based medicine in medical school. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000 Mar; 67(2):163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordley DR, Fagan M, and Theige D. Evidence-based medicine: a powerful educational tool for clerkship education. Am J Med. 1997 May; 102(5):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical School Objectives Project Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education—guidelines for medical schools: report 1 of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999 Jan; 74(1):13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward G. Miner Library, University of Rochester Medical Center. Informatics competencies for medical students at the University of Rochester Medical Center: planning documents, 1995. [Web document]. Rochester, NY: The Library, 1995. [cited 1 Feb 2000]. <http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/Miner/Educ/medinfostudents1.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Health Sciences Center Library, University of New Mexico. Integrated health informatics initiative (IHII). Albuquerque, NM: The Library, 2000:4 leaves. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2d ed. Edinburgh, Scotland, U.K.: Churchill-Livingstone, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Medical School Objectives Project Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education—guidelines for medical schools: report 1 of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999 Jan; 74(1):13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows S, Ginn DS, Love N, and Williams TL. A strategy for curriculum integration of information skills instruction. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Jul; 77(3):245–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows SC, Tylman V. Evaluating medical student searches of MEDLINE for evidence-based information: process and application of results. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999 Oct; 87(4):471–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2d ed. Edinburgh, Scotland, U.K.: Churchill-Livingstone, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S. Critically appraised topics (CATs). Can Assoc Radiol J. 2001 Oct; 52(5):286–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyer PC. The critically appraised topic: closing the evidence-transfer gap. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Nov; 30(5):639–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SH, Kaiser S, Morgan LK, Sullivan J, Siu A, Rose D, Rico M, Smith L, Schechter C, Miller M, and Stagnaro-Green A. An integrated program for evidence-based medicine in medical school. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000 Mar; 67(2):163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordley DR, Fagan M, and Theige D. Evidence-based medicine: a powerful educational tool for clerkship education. Am J Med. 1997 May; 102(5):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson CC, Morrison RD, and Ullian JA. A medical school-managed care partnership to teach evidence-based medicine. Acad Med. 2000 May; 75(5):526–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SH, Kaiser S, Morgan LK, Sullivan J, Siu A, Rose D, Rico M, Smith L, Schechter C, Miller M, and Stagnaro-Green A. An integrated program for evidence-based medicine in medical school. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000 Mar; 67(2):163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KM, Rivera J, and Arriaga J. Informatics training to prepare faculty for a new case-based medical school curriculum. Poster presentated at: MLA 2001, 101st Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; Orlando, FL; May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. AAMC outcome project general competencies. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: The Council, 2002. [cited 18 Apr 2002]. <http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp>. [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. President's memoranda 2000: information: lifelong professional development and maintenance of competence. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The Association, 2000. [cited 18 Apr 2002]. < http://www.aamc.org/private/refctr/afad/deanmemo/dm20000/00_32.htm>. (Registration required). [Google Scholar]