Abstract

Background

Sitosterolemia is an autosomal recessive disorder that maps to the sitosterolemia locus, STSL, on human chromosome 2p21. Two genes, ABCG5 and ABCG8, comprise the STSL and mutations in either cause sitosterolemia. ABCG5 and ABCG8 are thought to have evolved by gene duplication event and are arranged in a head-to-head configuration. We report here a detailed characterization of the STSL in Caucasian and African-American cohorts.

Methods

Caucasian and African-American DNA samples were genotypes for polymorphisms at the STSL locus and haplotype structures determined for this locus

Results

In the Caucasian population, 13 variant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified and resulting in 24 different haplotypes, compared to 11 SNPs in African-Americans resulting in 40 haplotypes. Three polymorphisms in ABCG8 were unique to the Caucasian population (E238L, INT10-50 and G575R), whereas one variant (A259V) was unique to the African-American population. Allele frequencies of SNPs varied also between these populations.

Conclusion

We confirmed that despite their close proximity to each other, significantly more variations are present in ABCG8 compared to ABCG5. Pairwise D' values showed wide ranges of variation, indicating some of the SNPs were in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) and some were not. LD was more prevalent in Caucasians than in African-Americans, as would be expected. These data will be useful in analyzing the proposed role of STSL in processes ranging from responsiveness to cholesterol-lowering drugs to selective sterol absorption.

Background

Although our diets contain an equal amount of cholesterol and plant sterols, only 30–60% of cholesterol and less than 5% of total plant sterols are absorbed daily [1,2]. Additionally, of the small amounts of non-cholesterol sterols (primarily plant sterols) that are absorbed, these are preferentially excreted into bile by the liver, resulting in a very low level of whole-body retention [2]. In sitosterolemia, intestinal discrimination between cholesterol and non-cholesterol sterols and the ability of the liver to excrete normally all sterols (cholesterol and non-cholesterol sterols) are disrupted [3]. Thus, the defect in sitosterolemia defines the molecular mechanisms by which these processes take place.

We mapped the sitosterolemia disease to a single locus, STSL, to chromosome 2p21 in a region defined by the markers D2S2294 and Afm210xe9 [4-6]. This locus has now been shown to comprise of two highly homologous genes, ABCG5 and ABCG8, arranged in a head-to-head organization [7,8]. Two mutations in either both copies of ABCG5 or both copies of ABCG8 result in sitosterolemia [7-9]. To date, sitosterolemia has not been reported to be caused by a person harboring a mutation in one allele of ABCG5 and one allele of ABCG8. These gene are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (liver and intestine only) and they are thought to function as obligate heterodimers [10]. Genetic analyses of STSL showed that despite their close proximity, ABCG8 shows a much greater genetic variability than ABCG5 [8]. This disparate genetic evolution seems to be unique to humans, as the mouse and rat STSL loci show relatively equal extent of variations in Abcg5 and Abcg8 [11,12]. At present, the implications of the relatively more conservation in ABCG5 compared to ABCG8 is not known. This seems remarkable, since both genes are highly homologous to each other, with preserved exon-intron structures and are also highly conserved from Man to Fugu [12].

The human genome is arranged in an array of haplotype blocks (haploblocks), characterized by segments of high LD followed by regions of low LD [13-17]. Haploblocks may have arisen from recombination hotspots that are never divided during meiosis [18,19] or may be randomly distributed due to uniform but rare recombination [20].

In this paper, we report the detailed characterization of the SNPs present at the STSL in Caucasians drawn from our cohort of sitosterolemia families, as well as a group of African-American individuals who were normal and healthy. These data allows us to characterize this locus in detail and define some of these haploblocks. Preliminary reports have implicated STSL in physiological processes ranging from responsiveness to 'statin' drugs used to lower plasma cholesterol, as well as more complex processes such as the metabolic syndrome [21-29]. The data reported herein should allow for a more detailed and definitive testing of these hypotheses.

Methods

SNP analyses

All studies were performed after Institutional Review Board approval and with informed consent of the participants. Genomic DNA was isolated from blood obtained from Caucasian patients and their family members as previously described [8]. African-American DNA samples came from the ongoing Sea Islands Families Project/Project Sugar at the Medical University of South Carolina [30,31]. These individuals are part of the larger Gullah-speaking ethnic community who were born and reared in the coastal Sea Islands of Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina, and whose parents were also reared on the Sea Islands. In the Project Sugar protocols, Type 2 diabetic probands are identified and then phenotypic data and DNA are obtained from the proband and the proband's family members. This database was screened for all individuals who were not diabetic and unrelated to each other to obtain a total of 46 unrelated individuals. Each exon and boundary intronic area of ABCG5 and ABCG8 was amplified by specific primers as previously described and SNPs detected by restriction enzyme digestion patterns [5,8] or by the primer extension method, using a capillary DNA analyzer (CEQ 8000, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). For the latter, amplified PCR products were digested with two units of Shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP, Roche Chemicals) and one unit of Exonuclease I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) at 37°C for one hour to remove unused primers and unincorporated nucleotides. The enzymes were inactivated by treating the samples at 75°C for 15 min. A primer extension reaction was set up using cleaned PCR products as template, the downstream primer adjacent to the SNP and fluorescent dideoxynucleotides. Multiplex extension reactions were carried out in some cases (details available on request). Samples were analyzed using a genetical analyzer, CEQ800 using the manufacturer's SNP separation method. Based upon the measured frequencies of each allele, observed genotypes were compared to expected genotypes for deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg principle. X2 values were calculated by comparing the observed and expected genotype frequencies using the formula Σ(observed-expected value)2/Expected value. P value was obtained from the X2 value table. The Age of mutation fixation was calculated as described by Guo and Xiong [32]. We selected 12 parents (24 chromosomes) carrying the commonest mutation, W361X, and where complete genotype information was available to compute recombination frequencies.

Haplotype analyses

Genotyping data were used to estimate haplotypes using SNPHAP program [33], PHASE v2.1 [34] and haploblocks were constructed using HaploBlockFinder v6 [35]. Linkage disequilibrium measures [36], D' and Δ2, were estimated between pairs of diallelic loci using the value of Lewontin's D' [37] and measured using the GOLD program [38].

Results

Our study consists of 32 parents (obligate carriers for mutations in either ABCG5 or ABCG8) of Caucasian origin from around the world [8]. Our African-American cohort consists of 46 unrelated individuals from the Sea Island community around South Carolina. Table 1 lists 23 SNPs (6 in ABCG5 and 17 in ABCG8) identified by extensive re-sequencing at the STSL locus by us, or those reported in the literature. The SNPS will be referred to as either by the amino acid they affect, or by their relative position in the gene. A formal identification for each of these SNPs is provided in Table 1. Only two loci in ABCG5, R50C and Q604E showed variations in our study population, the remaining 4 SNPs were invariant in all subjects and are not depicted in the haplotype analyses. For ABCG8, only 12 variable loci were identified, marked by an asterisk, Table 1, the remaining were non-variant in our study samples. All of the SNPs shown in Table 1 except M429V in ABCG8 were analyzed. M429V was reported only recently in a Japanese cohort [29], and was not included for analyses in this study. However, in limited analyses, we did not detect this in any of our previously sequenced exon 9 DNA traces either (data not shown), suggesting it may have a very low prevalence. Thus, only 14 SNPs (asterisked, Table 1) constitute the haplotypes shown and are ordered with ABCG5, followed by ABCG8.

Table 1.

Polymorphisms reported at the STSL locus

| Name | Position in the gene | Polymorphism | dbSNP cluster ID | Restriction enzyme site altered | Nucleotide Position |

| ABCG5 | |||||

| P9P | Exon 1 | C/T | rs49854016 | BstN 1 | 22881725 |

| R50C* | Exon 2 | C/T | rs6756629 | - | 22881023 |

| V523I | Exon 11 | G/A | ss49854017 | - | 22863069 |

| C600Y | Exon 13 | G/A | ss49854018 | - | 22856345 |

| Q604E* | Exon 13 | G/C | rs6720173 | Sml I | 22856334 |

| V622M | Exon 13 | G/A | ss49854019 | - | 22856280 |

| ABCG8 | |||||

| 5' UTR-41 | 5' UTR | C/T | ss49854020 | BstE II | 22882085 |

| 5' UTR-19* | 5' UTR | T/G | rs3806471 | Tsp45 I | 22882107 |

| P17P | Exon 1 | G/C | ss49854021 | - | 22882176 |

| D19H* | Exon 1 | G/C | rs11887534 | - | 22882180 |

| INT1-21* | Intron 1 | C/A | ss4148209 | Mnl I | 22887558 |

| INT1-7* | Intron 1 | C/T | ss4148210 | BsmA 1 | 22887572 |

| C54Y* | Exon 2 | G/A | ss4148211 | SexA I | 22887676 |

| E238L* | Exon 6 | G/A | ss49854010 | - | 22895692 |

| A259V* | Exon 6 | C/T | ss49854012 | Hae III | 22895756 |

| Q340E | Exon 7 | C/G | ss49854024 | - | 22915101 |

| T400K* | Exon 8 | C/A | ss4148217 | Mse I | 22915366 |

| M429V | Exon 9 | G/A | - | 22916932 | |

| INT9-19 | Intron 9 | C/T | ss49854025 | - | 22917460 |

| INT10-50* | Intron 10 | C/T | ss4148220 | - | 22918168 |

| A565A* | Exon 11 | C/T | ss4148221 | - | 22918424 |

| G575R* | Exon 11 | G/C | rs49584011 | Hha I | 22918452 |

| A632V* | Exon 13 | C/T | rs6544718 | Sty I | 22920858 |

*Only these SNPs were found to be variant in the present study and the haplotypes (See Table 2 and 3) are ordered with these reported in sequence. The SNPs shown in bold (4th column) are ones that also part of the HapMap dataset. Nucleotide numbering according to GenBank Sequence ID NT_022184.

The A259V polymorphism was present only in African-Americans. The C/T polymorphism at INT10-50 position, E238L and G575R in ABCG8 were variable only in the Caucasians. The haplotypes shown comprise all of the marked loci in both groups (Table 1) in order. Among the unrelated parents (Caucasians) all the SNPs, except R50C were in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (p > 0.005, χ Square test). To completely characterize the haplotype structure, we estimated haplotype frequencies in each sample population using the multi-locus genotype data for each sample population. Estimates of haplotype frequencies are presented in Tables 2 and 3 for the Caucasians and African-Americans, respectively. These frequencies were estimated using the method described by Excoffier and Slatkin [33] as implemented in the SNPHAP program (Electronic Database Information).

Table 2.

Estimated haplotype frequencies for Caucasians

| Haplotype* | Est. Freq. | Cum. Freq. |

| 11111111111111 | 0.229 | 0.229 |

| 11111111121111 | 0.224 | 0.453 |

| 11111121111111 | 0.083 | 0.536 |

| 11211121111111 | 0.063 | 0.599 |

| 11111121121111 | 0.042 | 0.641 |

| 21111111121111 | 0.031 | 0.672 |

| 21212221111112 | 0.031 | 0.703 |

| 11111121111112 | 0.031 | 0.734 |

| 11212221111111 | 0.031 | 0.766 |

| 21122221111111 | 0.016 | 0.781 |

| 21112111121112 | 0.016 | 0.797 |

| 21211221112111 | 0.016 | 0.813 |

| 11211121111211 | 0.016 | 0.828 |

| 11212211112111 | 0.016 | 0.844 |

| 21112221121111 | 0.016 | 0.859 |

| 11112122112112 | 0.016 | 0.875 |

| 12121111111112 | 0.016 | 0.891 |

| 11111121112112 | 0.016 | 0.906 |

| 22111111121111 | 0.016 | 0.922 |

| 11112121121111 | 0.016 | 0.938 |

| 11112221111112 | 0.016 | 0.953 |

| 21212221121212 | 0.016 | 0.969 |

| 11211111111122 | 0.016 | 0.984 |

| 11112111111111 | 0.016 | 1.000 |

*The left to right order of the haplotype reports on the asterisked SNPs shown top to bottom in Table 1.

Table 3.

Estimated haplotype frequencies for African-Americans

| Haplotype* | Est. Freq | Cum Freq |

| 11111121111111 | 0.099 | 0.099 |

| 11111221121111 | 0.076 | 0.175 |

| 11111121111211 | 0.071 | 0.246 |

| 11111111111211 | 0.070 | 0.316 |

| 11111111121111 | 0.059 | 0.376 |

| 11111121121111 | 0.054 | 0.430 |

| 11111111111111 | 0.041 | 0.471 |

| 11111221111111 | 0.034 | 0.505 |

| 21111211121111 | 0.030 | 0.535 |

| 21112221111111 | 0.030 | 0.564 |

| 21111121121111 | 0.028 | 0.592 |

| 12121221111111 | 0.022 | 0.614 |

| 21212111111211 | 0.022 | 0.636 |

| 11211111111211 | 0.022 | 0.657 |

| 11121121221111 | 0.022 | 0.679 |

| 21111111121211 | 0.022 | 0.701 |

| 21111121111211 | 0.021 | 0.721 |

| 21111211111111 | 0.020 | 0.742 |

| 11112121121111 | 0.016 | 0.757 |

| 21111211111211 | 0.015 | 0.772 |

| 11112211111111 | 0.012 | 0.785 |

| 21111111121111 | 0.012 | 0.797 |

| 11211221211111 | 0.011 | 0.808 |

| 11211121111111 | 0.011 | 0.818 |

| 11221121111211 | 0.011 | 0.829 |

| 11211211111111 | 0.011 | 0.840 |

| 11211211111211 | 0.011 | 0.851 |

| 11112121221111 | 0.011 | 0.862 |

| 11121111111111 | 0.011 | 0.873 |

| 11111221211211 | 0.011 | 0.884 |

| 11112121111112 | 0.011 | 0.895 |

| 11221111111211 | 0.011 | 0.905 |

| 11111221121211 | 0.011 | 0.916 |

| 21121121111111 | 0.011 | 0.927 |

| 11111211221111 | 0.011 | 0.938 |

| 21112121221211 | 0.011 | 0.949 |

| 21112121211211 | 0.011 | 0.960 |

| 11211211211111 | 0.011 | 0.971 |

| 21111221111112 | 0.011 | 0.982 |

| 21122211111111 | 0.011 | 0.992 |

*The left to right order of the haplotype reports on the asterisked SNPs shown top to bottom in Table 1.

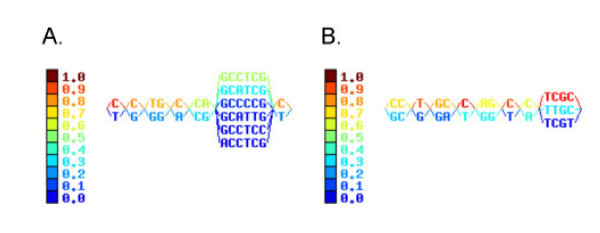

The frequencies of the minor alleles varied from 0.02632 to 0.5 shown by different color code in Fig. 1. Twenty-four haplotypes were constructed from 64 chromosomes with the SNP signature CCTGCCGGCCTCGC haplotype as the most common among Caucasians, accounting for ~23% of the haplotypes (Table 2). For SNPs that affect amino acids, this translates to E604-R50-D19-C54-E238-A259-T400-A565-G575-A632. The next common Caucasian haplotype differs from this one in that there is a lysine at position 400 in ABCG8 (K400) and these two haplotypes account for ~45% of all haplotypes. There were many minor haplotypes whose contribution was very low (Table 2). The haplotypes were divided into seven blocks. The haplotype data is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Haploblock structure of STSL in Caucasians and in African-Americans. Haploblocks were constructed as described in Methods. The color bars indicate the frequencies with which each of the haploblock sequences are found. Note the larger haploblock arrangements in Caucasians (panel A), compared to that observed in African-Americans (panel B).

In the case of African-Americans, we identified four SNPs whose prevalence deviated significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (5' UTR-19, D19H, A259V, A565A) all of which are located in ABCG8. Minor allele frequencies varied from 0.02174 to 0.38043. Haplotypes were divided into eight blocks as shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, a SNP that results in A259V in ABCG8 was detected in this cohort, but was absent in Caucasians, and a SNP that was variant in Caucasian (E238L in ABCG8) but was non-variant in African-Americans. The cumulative frequency shown (Table 3) does not sum to 1 in the African-American sample population. We deleted from the list of haplotypes those whose estimated frequencies were less than 1/(2 × 46) ~0.00107, since there are only 92 total haplotypes in all 46 individuals. Forty haplotypes were constructed, of which the signature CCTGCCGGCCTCGC was the major haplotype (~9.9%), translating to a coding haplotype of E604-R50-D19-C54-E238-A259-T400-A565-G575-A632, identical to the commonest Caucasian haplotype. However, the second commonest haplotype in Caucasians, with the K400 change was not detected at all in the African-Americans. Note the large numbers of haplotypes with the lower frequencies detected in the African-Americans, compared to the Caucasian samples.

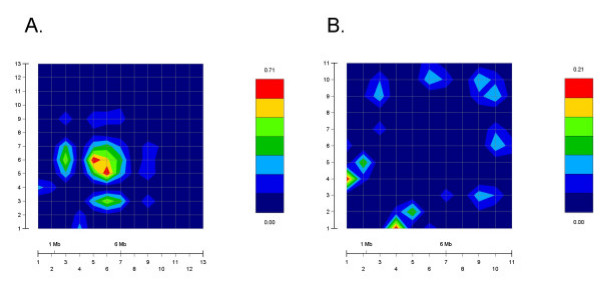

Figure 2.

GOLD plot of pair-wise Δ2 values for SNPs in Caucasians and African-Americans. As a pictorial depiction of LD at the STSL, GOLD plots for Caucasians (panel A) and African-Americans (panel B) were plotted. Note the differences in the color scales between the two panels shown on the right-hand side of each plot. Overall, a small area of LD was present in the Caucasian sample, as shown by the increased red intensity, almost all of this was accounted for an area involving intron 1. For African-Americans, very little LD was present (compare the GOLD plots with Table 4).

Table 4 presents results of pair-wise linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis for the fourteen SNPs at the STSL locus in these two populations (African-American and Caucasian). In this table, we present the pair of loci considered (columns labeled M1 and M2), the value of the Chi-square statistic (column labeled ChiSq) that tests whether D' (a measure of LD [37]) is non-zero, the p-value corresponding to the Chi-square statistic (column labeled Pval), and estimates of two measures of linkage disequilibrium, Δ2 [36] and D' [37]. Both measures of linkage disequilibrium range between 0 and 1, 0 meaning no LD and 1 meaning complete disequilibrium. Although we computed LD values for pairs of markers, we present results only for those pairs whose p-value for the Chi-square statistic is less than 0.10 in the interest of consolidation of results. Pair-wise LD was calculated using GOLD program (Fig. 2, regions red in color indicate high LD values). Caucasians (Fig. 2A) appear to have larger pair-wise Δ2 for consecutive markers more frequently than do African-Americans (Fig. 2B). Of note, for the non-synonymous SNPs, R50C and D19H showed some LD in both populations, though the Ch-square statistic was only moderate (Table 4). Amongst Caucasians, the strongest LD was observed between the two intronic SNPs, INT1-12 and INT1-7, and to a lesser extent between INT1-7 and both 5'UTR-19 and Q604E (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of pair-wise LD analyses

| Population | M1 | M2 | ChiSq | Pval | Δ2 | D' |

| Caucasian | INT1-21 | INT1-7 | 20.01 | 1E-05 | 0.545 | 0.866 |

| 5'UTR-19 | INT1-7 | 9.61 | 0.002 | 0.256 | 0.594 | |

| Q604E | INT1-7 | 7.14 | 0.008 | 0.239 | 0.489 | |

| T400K | A632V | 6.13 | 0.013 | 0.125 | 1.000 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | T400K | 5.84 | 0.016 | 0.153 | 1.000 | |

| Q604E | D19H | 5.02 | 0.025 | 0.174 | 1.000 | |

| INT1-7 | T400K | 4.94 | 0.026 | 0.111 | 1.000 | |

| R50C | D19H | 4.79 | 0.029 | 0.234 | 0.484 | |

| INT1-21 | T400K | 4.45 | 0.035 | 0.153 | 1.000 | |

| E238L | INT10-50 | 4.42 | 0.036 | 0.238 | 1.000 | |

| INT1-7 | C54Y | 4.41 | 0.036 | 0.138 | 0.739 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | C54Y | 4.24 | 0.040 | 0.134 | 0.619 | |

| T400K | INT10-50 | 3.92 | 0.048 | 0.040 | 1.000 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | A565A | 3.86 | 0.049 | 0.127 | 1.000 | |

| Q604E | INT1-21 | 3.66 | 0.056 | 0.128 | 0.420 | |

| INT10-50 | A632V | 3.29 | 0.070 | 0.132 | 0.641 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | INT1-21 | 2.86 | 0.091 | 0.071 | 0.267 | |

| C54Y | T400K | 2.74 | 0.098 | 0.082 | 0.433 | |

| African-American | 5'UTR-19 | T400K | 11.01 | 9E-04 | 0.080 | 1.000 |

| INT1-7 | A565A | 8.09 | 0.004 | 0.085 | 0.587 | |

| R50C | D19H | 6.96 | 0.008 | 0.205 | 1.000 | |

| T400K | A565A | 6.56 | 0.010 | 0.088 | 0.557 | |

| Q604E | INT1-21 | 5.82 | 0.016 | 0.119 | 0.505 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | A565A | 5.10 | 0.024 | 0.059 | 0.460 | |

| C54Y | A565A | 3.93 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.270 | |

| 5'UTR-19 | C54Y | 3.49 | 0.062 | 0.047 | 0.481 | |

| R50C | INT1-7 | 3.05 | 0.081 | 0.044 | 1.000 | |

| INT1-7 | A632V | 3.05 | 0.081 | 0.044 | 1.000 | |

| Q604E | D19H | 3.01 | 0.083 | 0.038 | 1.000 |

M1 = 1st marker in pair of SNPs, M2 = 2nd marker in pair of SNPs, ChiSq = Value of chi-square test of association, Pval = Two-sided P-value corresponding to chi-square value in ChiSq column assuming 1 degree of freedom.

Δ2 = Estimated value of Delta-squared measure of LD.

D' = Estimated value of Lewontin's [37] measure of LD.

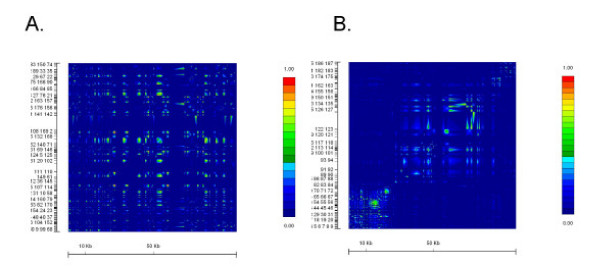

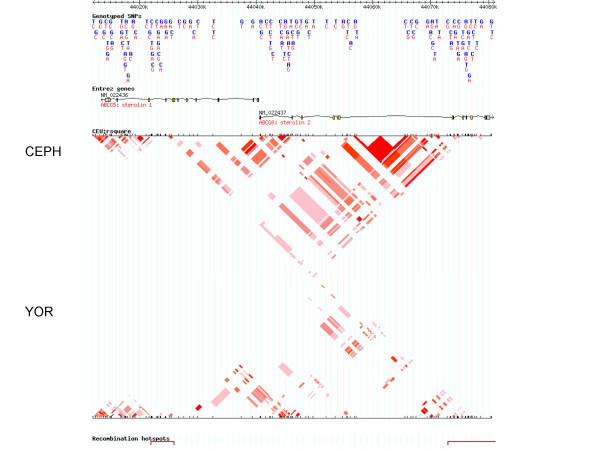

With the publication of the HapMap data during the preparation and submission of this manuscript [39], we were able to compare our data with that of the HapMap data (available at [40]). We compared data for SNPs typed on chromosome 2, between positions 44,012,000 to 44,081,000, containing the STSL locus. The GOLD plots for Caucasian samples (CEPH family data) and African samples (Yoruba samples from Nigeria) are shown in Fig. 3. The HapMap data for this region is much denser. Additionally, there are some significant differences between SNPs used in our study and those reported by the HapMap Consortium. Firstly, of the 14 SNPs we found were variant in our entire cohort, only 8 of these were also genotyped by the HapMap Consortium, highlighted in Table 1. Secondly, of the 6 that are unique to our genotyping, 5 of these are cSNPs and are all non-synonymous changes, and the 6th, INT1-21, was one where we detected significant LD for Caucasian samples (See Fig. 2A). Of the remaining 9 SNPs we genotyped and found no variants (Table 1), with the exception of M429V, which we did not genotype, the HapMap Consortium also do not report any genotyping data. It is not clear to us whether this is because they also failed to show these were variant, or because these were not tested. Nevertheless, given the richness of the HapMap dataset, we present the Haploview analyses (which allows for a better pictorial representation than GOLD for large data sets) for these two populations (Fig. 4), which are essentially the screen-shots available at their website [40], with some image cropping for presentation. Note that there are 2 hot-spots of recombination that can be identified and these are located at the ends of both ABCG5 and ABCG8 (Fig. 4). Despite differences highlighted between the HapMap Data and ours, the overall conclusions are similar; in both analyses, the samples originating in peoples from Africa show the least amount of linkage disequilibrium, the greatest variability and smaller haploblocks (data not shown), compared to Caucasian samples. The differences between our samples may also be significant. Our Caucasian samples are drawn from families with sitosterolemia and come from many different parts of the World. Our African-American samples, while maintaining a much closer genetic tie to Africa, are drawn from peoples from a variety of Africans originating from West Africa, not just the Yoruba, in Nigeria [30].

Figure 3.

GOLD plot of pair-wise Δ2 values for SNPs in CEPH and Yoruba Africans genotyped by the HapMap Consortium. We analyzed the SNP genotypes spanning the STSL locus for the CEPH (panel A) and Yoruba (panel B) samples available at http://www.hapmap.org. The HapMap SNP dataset are much more dense. Note that the Yoruba samples show very little LD compared to the Caucasian samples. Additionally, the Caucasian samples also show that the STSL locus does not have any large segments of LD.

Figure 4.

Haploview analyses of CEPH and Yoruba Africans genotyped by the HapMap Consortium. Using the data and analyses available at the website, http://www.hapmap.org, we selected the genotypes for the CEPH and Yoruba populations. The CEPH LD plot, using Haploview is shown above the Yoruba plot (inverted). As can be seen, for both, there is little evidence of significant LD for the SNP makers used. Additionally, two hotspots for recombination were identified (depicted by the red bars at the bottom of the picture), located at the ends of the STSL locus and involve the terminal exons of both ABCG5 and ABCG8 (which contain the transmembrane domains).

Age of mutation was calculated considering W361X as the most common disease causing mutation. Table 5 summarizes the data linking the estimated age of mutation with the alleles. Of the non-synonymous cSNPs, T400K of ABCG8 was found to be oldest polymorphism that arose about 2387 generations ago (~47,000 y). This SNP was also closely spaced to W361X mutation. The youngest cSNPS was estimated to be ~180 y old (C54Y). The only cSNP we could estimate by this methodology in ABCG5 was Q604E (~4,000 y old). We could not estimate the ages in some of the SNPs due to insufficient information to allow us to estimate recombination frequencies (indicated by NA, Table 5).

Table 5.

Estimation of age of polymorphism fixation.

| SNP | Allele | Number of Disease Chromosomes* | Number of Healthy Chromosomes* | Frequency (disease chromosome) | Frequency (healthy chromosome) | Recombination Fraction | Age Estimate (generations) |

| R50C | C | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | |

| Q604E | G | 2 | 1 | 0.167 | 0.083 | 0.058833 | 17.7 |

| 5'UTR-19 | T | 11 | 10 | 0.917 | 0.833 | 0.033059 | 9.1 |

| D19H | G | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA |

| INT1-21 | C | 12 | 7 | 1 | 0.583 | 0.005 | 0 |

| INT1-7 | C | 11 | 11 | 0.917 | 0.917 | NA | |

| C54Y | A | 9 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.417 | 0.02749 | 8.8 |

| E238L | G | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | |

| T400K | A | 10 | 3 | 0.833 | 0.25 | 0.0002 | 2387 |

| INT10-50 | T | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | |

| A565A | C | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | |

| G575R | G | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | NA | |

| A632V | C | 11 | 10 | 0.917 | 0.833 | 0.005692 | 52.9 |

*Out of a total of 12 disease and 12 normal chromosomes, see Methods

Discussion

There are several reports correlating defects in a polygenic disease with single nucleotide changes in the coding or regulatory regions. SNPs also offer a substantial advantage in linkage disequilibrium-based studies of disease gene mapping [41], pharmacogenetics [42] and human evolution [43]. Studies of African, Asian and European Caucasian populations have shown that both a dense marker set, as well as larger sample size will be needed for a stable fine-scale depiction of haploblocks [44,45]. Variations in APOD gene were associated with an increased risk of early onset of Alzheimer's disease in a group of Finns [46]. Responses to pharmacotherapy also vary from person to person and in part can be accounted for by genetic variations and haplotype structures [47]. Thus characterization of SNPs, as well as the haploblock structures will be useful in defining the roles of genes in health and disease. We have characterized SNPs present at the STSL locus in Caucasian families with sitosterolemia and in a group of normal healthy African-Americans. This locus is important as its disruption leads to the human disorder, sitosterolemia [3]. More importantly, this locus comprises of two genes, ABCG5 and ABCG8, which are critical in handling of dietary sterols and for biliary sterol excretion [48]. Thus they are important in whole body sterol balance and have been implicated in cardiovascular health. A number of studies have been implicated this locus in disease (or physiological) processes ranging from lipoprotein kinetics [22], cholesterol absorption [27,29], obesity [27] to response to drug therapy [26].

When performing power and sample size calculations for disease or QTL genetic association, a critical parameter is some measure of linkage disequilibrium between the trait and marker locus [49-52]. Because the trait locus is unobserved, this parameter is usually unknown. A surrogate measure is some average marker-marker linkage disequilibrium measure [53]. Our work determining marker-marker linkage disequilibrium for SNPs in the ABCG5/ABCG8 gene cluster will enable researchers to perform more realistic power and sample size calculations for genetic association studies involving the ABCG5/ABCG8 cluster. Prior to placing these studies in context of the data reported herein, there are some important points that need highlighting about our study. While this manuscript was in submission, the HapMap data were reported [39]. This latter dataset is not only more dense, it examined 4 different populations. The Chinese and Japanese samples show significantly more LD over this area, with much larger haploblock structures than the Yoruba and the CEPH populations (data not show, but available at [40]). These data are in keeping with our analyses of the high degree of homozygosity for markers spanning the STSL locus in families with sitosterolemia originating from Japan or China [5]. However, comparison of the SNPs we genotyped to those in the HapMap dataset showed that a significant number of cSNPs we genotyped were not analyzed in the HapMap dataset (see Table 1). Additionally, one cSNP, M429V, which was reported to be relatively more frequent in the Japanese population [29], was also absent from the HapMap dataset analyzing the Chinese Han and the Tokyo Japanese DNA samples. Thus our analyses presented herein add to this body of knowledge.

We noted a number of differences between the Caucasian and African-American populations. Some of these are expected. For example, the African-American population sampled contains many more variations and haplotypes. Additionally, the haploblock structures were smaller and the extent of linkage disequilibrium between markers was lower, in keeping with the Out-of-Africa theory for the origins of humans. This was true for both our dataset as well as analyses of the HapMap dataset. Some exceptions are notable. SNPs in intron 1 of ABCG8 show some linkage to a common non-synonymous SNP, Q604E, in ABCG5, but present in exon 13 (almost 20 kb apart). It is not clear if the intronic variations have a regulatory effect on transcription, but these data draw attention to this possibility. The transcriptional regulation of STSL remains poorly characterized, with few definitive studies to indicate which regulatory transcriptional factors, as well as nucleotide sequences are involved.

Four SNPs, 5' UTR-19, D19H, A259V, and A565A, in ABCG8 were not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for the African-Americans. One explanation is sampling error. Since the unrelated African-American samples were gleaned from a sample collected for the presence of diabetes and family members ascertained, it is possible that, despite genealogical screens to remove related samples etc., some non-randomness error has skewed the data. This error may be compounded by the small sample size. Another explanation is that there may be a selection process that has led to this. We favor the first explanation, although this issue will only be resolved with analyses of a much larger sample. Secondly, we confirm that despite the relative proximity of ABCG5 to ABCG8, there was significantly less variation observed for ABCG5 and would suggest some selection or difference in mutational rates and fixation between ABCG5 and ABCG8. Since ABCG5 and ABCG8 are proposed to function as obligate heterodimers [54], and complete mutations in either gene seems to result in an identical phenotype [8], these genetic findings posit an enigma. It is not clear what selective pressures may be responsible for this, if any. In rodents, almost equal variations are noted in Abcg5 and Abcg8 [11,12]. It will be of some interest to see if this difference in ABCG5/ABCG8 variability is present in populations related to Man, such as Chimpanzees and other greater apes. We note that in the HapMap dataset, there are many more SNPs reported for ABCG5. However, all of these are exclusively located in the non-coding regions and, to date, there are more cSNPs in ABCG8 than there are in ABCG5. A number of association studies reporting linkage of certain SNPs at the STSL locus to a number of seemingly unconnected phenotypes, ranging from response to a cholesterol-lowering drug, to insulin sensitivity and lipoprotein kinetics in obese subjects have been reported. Unfortunately, these do not intuitively allow for a selective advantage, positive or negative, that can explain the differences in the variability between ABCG5 and ABCG8.

Compared to other markers, SNPs have a lower mutation rate and are valuable for estimating age of mutations. SNPs in ABCG5 appear to be newly created compared to those in ABCG8. Additionally, in this study, we could not replicate the identification of other polymorphic variants in ABCG5, including some we have reported previously [8]. These are P9P, V532I and V622M. This may reflect the rarity of these SNPs and our small sample size. If so, to investigate the role of these SNPs in biology may require a much larger sample size. Additionally, these SNPs may be race-related. For example, the M429V SNP was reported in the Japanese samples and seems to play a role in cholesterol absorption [29]. However, we were not able to detect this SNP in either the Caucasian or the African-American samples. Additionally this SNP was also not reported in the Japanese and Chinese cohort in the HapMap dataset. Thus, this SNP may represent another race-specific polymorphism.

Conclusion

We report a detailed characterization of the STSL locus, present data that show regions of LD at this locus and provide data that should allow for more accurate Power calculations for studies examining the role of this locus in human biology. Our dataset has uniquely analyzed SNPS not reported in by the SNP consortium and therefore add to this knowledge base.

Abbreviations

ABC; ATP binding cassette, SNP; single nucleotide polymorphism. STSL; sitosterolemia locus.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BP, G-SA, SEH, DG and SBP generated data and analyzed them. BP and SBP wrote the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Drs. W. Timothy Garvey and David McLean, and all the participants of Project Sugar for allowing us access to the Gullah DNA samples. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI, PHS HL060613 (SBP) and by the Daejeon University Research Fund of 2003 (G-SA).

Contributor Information

Bhaswati Pandit, Email: bhaswati.pandit@mssm.edu.

Gwang-Sook Ahn, Email: ahngs@dju.ac.kr.

Starr E Hazard, Email: Hazard@musc.edu.

Derek Gordon, Email: gordon@biology.rutgers.edu.

Shailendra B Patel, Email: sbpatel@mcw.edu.

References

- Gould RG, Jones RJ, LeRoy GV, Wissler RW, Taylor CB. Absorbability of beta-sitosterol in humans. Metabolism. 1969;18:652–662. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(69)90078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salen G, Ahrens EJ, Grundy SM. Metabolism of beta-sitosterol in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1970;49:952–967. doi: 10.1172/JCI106315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya AK, Connor WE. Beta-sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. A newly described lipid storage disease in two sisters. J Clin Invest. 1974;53:1033–1043. doi: 10.1172/JCI107640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SB, Salen G, Hidaka H, Kwiterovich PO, Stalenhoef AF, Miettinen TA, Grundy SM, Lee MH, Rubenstein JS, Polymeropoulos MH, Brownstein MJ. Mapping a gene involved in regulating dietary cholesterol absorption. The sitosterolemia locus is found at chromosome 2p21. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1041–1044. doi: 10.1172/JCI3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Gordon D, Ott J, Lu K, Ose L, Miettinen T, Gylling H, Stalenhoef AF, Pandya A, Hidaka H, Brewer JB, Kojima H, Sakuma N, Pegoraro R, Salen G, Patel SB. Fine mapping of a gene responsible for regulating dietary cholesterol absorption; founder effects underlie cases of phytosterolemia in multiple communities. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:375–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Lee MH, Carpten JD, Sekhon M, Patel SB. High-Resolution Physical and Transcript Map of Human Chromosome 2p21 Containing the Sitosterolemia Locus. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:364–374. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Lee MH, Hazard S, Brooks-Wilson A, Hidaka H, Kojima H, Ose L, Stanlenhoef AFH, Mietinnen T, Bjorkhem I, Brukert E, A. P, Brewer HB, Salen G, Dean M, Srivastava A, Patel SB. Two genes that map to the STSL locus cause sitosterolemia: Genomic structure and spectrum of mutations involving sterolin-1 and sterolin-2, encoded by ABCG5 and ABCG8 respectively. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:278–290. doi: 10.1086/321294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, Yu H, Shulenin S, Hidaka H, Kojima H, Allikmets R, Sakuma N, Pegoraro R, Srivastava AK, Salen G, Dean M, Patel SB. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nature Genetics. 2001;27:79–83. doi: 10.1038/87170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf GA, Li WP, Gerard RD, Gelissen I, White A, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:659–669. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Lee MH, Yu H, Zhou Y, Sandell SA, Salen G, Patel SB. Molecular cloning, genomic organization, genetic variations, and characterization of murine sterolin genes Abcg5 and Abcg8. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:565–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Pandit B, Klett E, Lee MH, Lu K, Helou K, Ikeda I, Egashira N, Sato M, Klein R, Batta A, Salen G, Patel SB. The rat STSL locus: characterization, chromosomal assignment, and genetic variations in sitosterolemic hypertensive rats. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2003;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly MJ, Rioux JD, Schaffner SF, Hudson TJ, Lander ES. High-resolution haplotype structure in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:229–232. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DB. Islands of linkage disequilibrium. Nat Genet. 2001;29:109–111. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N, Berno AJ, Hinds DA, Barrett WA, Doshi JM, Hacker CR, Kautzer CR, Lee DH, Marjoribanks C, McDonough DP, Nguyen BT, Norris MC, Sheehan JB, Shen N, Stern D, Stokowski RP, Thomas DJ, Trulson MO, Vyas KR, Frazer KA, Fodor SP, Cox DR. Blocks of limited haplotype diversity revealed by high-resolution scanning of human chromosome 21. Science. 2001;294:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1065573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegele RA, Plaetke R, Lalouel JM. Linkage disequilibrium between DNA markers at the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene. Genet Epidemiol. 1990;7:69–81. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370070114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys AJ, Ritchie A, Neumann R. High resolution analysis of haplotype diversity and meiotic crossover in the human TAP2 recombination hotspot. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:725–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys AJ, Kauppi L, Neumann R. Intensely punctate meiotic recombination in the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex. Nat Genet. 2001;29:217–222. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Akey JM, Wang N, Xiong M, Chakraborty R, Jin L. Randomly distributed crossovers may generate block-like patterns of linkage disequilibrium: an act of genetic drift. Hum Genet. 2003;113:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0941-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggemans RM, Zock PL, Tai ES, Ordovas JM, Molhuizen HO, Katan MB. ATP binding cassette G5 C1950G polymorphism may affect blood cholesterol concentrations in humans. Clin Genet. 2002;62:226–229. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Watts GF, Barrett PH, Whitfield AJ, van Bockxmeer FM. ATP-binding cassette transporter G8 gene as a determinant of apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics in overweight men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2188–2191. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143532.93729.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubacek JA, Berge KE, Stefkova J, Pitha J, Skodova Z, Lanska V, Poledne R. Polymorphisms in ABCG5 and ABCG8 transporters and plasma cholesterol levels. Physiol Res. 2004;53:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajinami K, Brousseau ME, Nartsupha C, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. ATP binding cassette transporter G5 and G8 genotypes and plasma lipoprotein levels before and after treatment with atorvastatin. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:653–656. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300278-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajinami K, Takekoshi N, Brousseau ME, Schaefer EJ. Pharmacogenetics of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: exploring the potential for genotype-based individualization of coronary heart disease management. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajinami K, Brousseau ME, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Interactions between common genetic polymorphisms in ABCG5/G8 and CYP7A1 on LDL cholesterol-lowering response to atorvastatin. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gylling H, Hallikainen M, Pihlajamaki J, Agren J, Laakso M, Rajaratnam RA, Rauramaa R, Miettinen TA. Polymorphisms in the ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes associate with cholesterol absorption and insulin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Plat J, Bragt MC, Mensink RP. Common sequence variations in ABCG8 are related to plant sterol metabolism in healthy volunteers. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:68–75. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400210-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa K, Inazu A, Kobayashi J, Higashikata T, Nohara A, Kawashiri M, Katsuda S, Takata M, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H. ATP-binding cassette transporter G8 M429V polymorphism as a novel genetic marker of higher cholesterol absorption in hypercholesterolaemic Japanese subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;109:183–188. doi: 10.1042/CS20050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra EJ, Kittles RA, Argyropoulos G, Pfaff CL, Hiester K, Bonilla C, Sylvester N, Parrish-Gause D, Garvey WT, Jin L, McKeigue PM, Kamboh MI, Ferrell RE, Pollitzer WS, Shriver MD. Ancestral proportions and admixture dynamics in geographically defined African Americans living in South Carolina. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114:18–29. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200101)114:1<18::AID-AJPA1002>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DCJ, Spruill I, Gevao S, Morrison EY, Bernard OS, Argyropoulos G, Garvey WT. Three novel mtDNA restriction site polymorphisms allow exploration of population affinities of African Americans. Hum Biol. 2003;75:147–161. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SW, Xiong M. Estimating the age of mutant disease alleles based on linkage disequilibrium. Hum Hered. 1997;47:315–337. doi: 10.1159/000154431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Slatkin M. Maximum-likelihood estimation of molecular haplotype frequencies in a diploid population. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:921–927. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Jin L. HaploBlockFinder: haplotype block analyses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1300–1301. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WG, Weir BS. Maximum-likelihood estimation of gene location by linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC. The Interaction of Selection and Linkage. Ii. Optimum Models. Genetics. 1964;50:757–782. doi: 10.1093/genetics/50.4.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abecasis GR, Cookson WO. GOLD--graphical overview of linkage disequilibrium. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:182–183. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Brooks LD, Chakravarti A, Collins FS, Daly MJ, Donnelly P. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Project [www.hapmap.org]

- Akey JM, Zhang K, Xiong M, Jin L. The effect of single nucleotide polymorphism identification strategies on estimates of linkage disequilibrium. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:232–242. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JF, Weale ME, Smith AC, Gratrix F, Fletcher B, Thomas MG, Bradman N, Goldstein DB. Population genetic structure of variable drug response. Nat Genet. 2001;29:265–269. doi: 10.1038/ng761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff SA, Verrelli BC. Patterns of human genetic diversity: implications for human evolutionary history and disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:293–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X, Hunt S, Tapper W, Lawrence R, Stavrides G, Ghori J, Whittaker P, Collins A, Morris AP, Bentley D, Cardon LR, Deloukas P. The impact of SNP density on fine-scale patterns of linkage disequilibrium. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:577–588. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Stephens JC, Zhao H. The impact of sample size and marker selection on the study of haplotype structures. Hum Genomics. 2004;1:179–193. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-1-3-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helisalmi S, Hiltunen M, Vepsalainen S, Iivonen S, Corder EH, Lehtovirta M, Mannermaa A, Koivisto AM, Soininen H. Genetic variation in apolipoprotein D and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol. 2004;251:951–957. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0470-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DB. Haplotype tagging in pharmacogenetics. Novartis Found Symp. 2005;267:14–9; discussion 19-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Lu K, Patel SB. Genetic basis of sitosterolemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:141–149. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Simonic I, Ott J. Significant evidence for linkage disequilibrium over a 5-cM region among Afrikaners. Genomics. 2000;66:87–92. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Vega FM, Gordon D, Su X, Scafe C, Isaac H, Gilbert DA, Spier EG. Power and sample size calculations for genetic case/control studies using gene-centric SNP maps: application to human chromosomes 6, 21, and 22 in three populations. Hum Hered. 2005;60:43–60. doi: 10.1159/000087918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Haynes C, Blumenfeld J, Finch SJ. PAWE-3D: visualizing Power for Association with Error in case/control genetic studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2005;In Press doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Finch SJ, Nothnagel M, Ott J. Power and sample size calculations for case-control genetic association tests when errors are present: application to single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Hered. 2002;54:22–33. doi: 10.1159/000066696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf GA, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Missense mutations in ABCG5 and ABCG8 disrupt heterodimerization and trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]