Abstract

The mammalian auditory sensory organ, the organ of Corti, consists of sensory hair cells with uniformly oriented stereocilia on the apical surfaces, displaying a distinct planar cell polarity (PCP) parallel to the sensory epithelium1-3. It is not clear how this polarity is achieved during differentiation4-5. Here we show that the organ of Corti is formed from a thicker and shorter post-mitotic primordium through unidirectional extension, characteristic of cellular intercalation known as convergent extension6. Mutations in the PCP pathway interfere with this extension, resulting a shortened and widened cochlea, as well as misorientation of stereocilia. Furthermore, parallel to the homologous pathway in Drosophila7,8, a mammalian PCP component Dishevelled2 displays PCP-dependent polarized subcellular localization across the organ of Corti. Together, these data suggest a conserved molecular mechanism for PCP pathways in invertebrates and vertebrates, and indicate that the mammalian PCP pathway might directly couple cellular intercalations to PCP establishment in the cochlea.

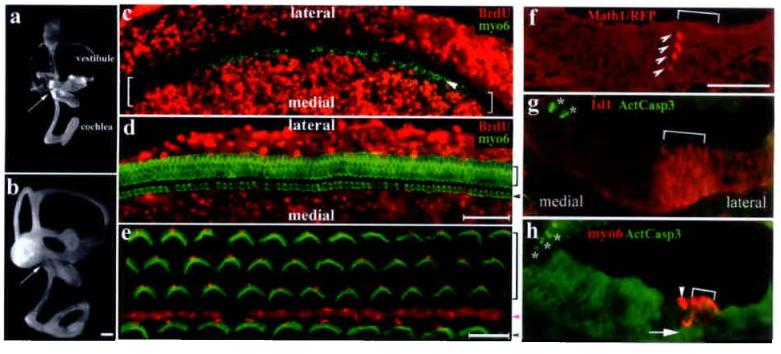

Between embryonic day 13 (E13) and E14, precursors for the organ of Corti can be identified as a zone of non-proliferating cells within the cochlear duct using BrdU pulse-labeling (Fig. 1c, brackets) 4,9-10. Subsequently, a gradient of cell differentiation within the precursor domain initiates near the base of the cochlea and leads to the patterning of one row of inner and three rows of outer hair cells (Fig. 1d, 1e) along the entire length of the cochlea by E18.510, with uniformly oriented stereocilia on the apical surface of hair cells (Fig. 1e, green). From E14.5 to E18.5, the length of the cochlea is increased approximately 2 fold (Fig. 1a-b). As viewed in cross sections, the developing organ of Corti in the same period is thinned from a 4-5 cell layered primordium (Fig. 1g) to only two layers of cells (Fig. 1h). One layer of hair cells lies above a layer of supporting cell nuclei whose cytoplasmic phalangeal processes reach the apexes of the hair cells, separating them from each other (Fig. 1h). Based on these observations, we have previously proposed that the longer and thinner mature organ is formed from a defined number of postmitotic precursor cells through integrated cellular intercalation movements4. BrdU chasing from E14 to E18 further indicated that there was no detectable cell mixing between the primordial organ of Corti and the surrounding cells (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, the hair cells at E14.5 marked by red fluorescent protein (Math1/RFP) were multi-cell layered (Fig. 1f) within the sensory primordium (Fig. 1g). The thinning of the sensory primordium is accomplished by E18.5 without detectable cell death (Fig. 1g-h).

Fig. 1.

Differentiation of the organ of Corti from its postmitotic precursor domain. a-b: Paint-filled inner ears at E14.5 (a) and E18.5 (b). Arrows indicate the base of the cochlea. Scale: 200 μm. c-e: Confocal scans of E14.5 (c) or E18.5 (d) cochlear whole-mounts pulse-labeled for 6 hours or chased with BrdU for 4 days, respectively, and double-stained for BrdU(red) and myosinVI (green). The bracket in (c) indicates the non-proliferating primordium, within which a row of inner hair cells (indicated by an arrowhead) is seen at the medial edge (c). By E18.5 (d), no BrdU+ cells were detected in the organ of Corti. The organ of Corti from a P1 animal (e) displays uniformly oriented stereocilia (green). The vortexes with a single kinocilium (red) of the V-shaped stereocilia point to the lateral side. Scale: 50 μm (c-d); 10 μm (e). f-h: The expression of Math1/RFP (f) marks the earliest hair cells in a multi-layered column (arrowheads) at the medial edge of the precursor domain (bracket), which is demarcated by Isl1 expression in E14.5 cross sections (g)27. By E18.5 (h), the organ of Corti has one layer of hair cells (red) above the layer of supporting cell nuclei (indicated by an arrow). No activated-caspase3+ cells (green in f and g, marked by asterisks) were detected within the organ of Corti from E14.5 to E18.5. Scale: 50 μm. Inner and outer hair cells were indicated by arrowheads and brackets (d, e, h), respectively. The magenta arrowhead (e) indicates the pillar cell region separating inner from outer hair cells.

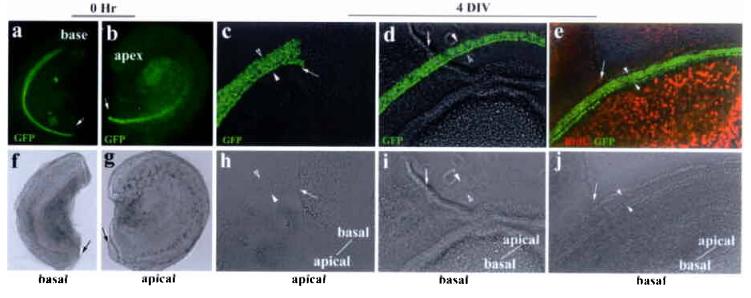

To further test our hypothesis, we bisected E14.5 cochlear epithelia into apical and basal portions, cultured them in a defined media. Using the cutting wound sites as reference points, we monitored the extension of the organ of Corti from apical-to-basal or basal-to-apical directions for the apical cultures or basal cultures, respectively (Fig. 2). At the beginning of the culture, hair cell differentiation is restricted to a single row of inner hair cells near the base (Fig. 2a-b) that has not yet reached the apex and outer hair cell region of the cochlea (Fig. 2a and 2b). After 4 days in vitro (DIV), hair cell differentiation progressed normally in both apical (Fig. 2c and 2h) and basal cultures (Fig. 2d-e, 2i-j). However, no extension of the organ of Corti was observed beyond the wound site in the apical cultures (Fig. 2c and 2h); whereas hair cell arrays extended beyond the wound site in the basal cultures (Fig. 2d-2e). This basal-to-apical extension was confirmed by cellular labeling of the cut cultures (supplemental Fig. 1). In addition, cells within the sensory region did not take up BrdU from the culture media, while surrounding cells incorporate BrdU as the basal cultures extended apically (Fig. 2e and 2j, notice the orientation of the cultures), indicating that only cells within the postmitotic precursor domain contribute to the extended organ of Corti.

Fig. 2.

Unidirectional extension of the organ of Corti in vitro. a-b: bisected basal (a) and apical (b) portions of the same cochlear duct. Nuclei-localized GFP is expressed under the control of Math1 enhancers4, marking the hair cells in live cultures. The bisection sites were indicated by arrows. Both the basal (basal culture) and apical (apical culture) portions of the cochlea were used for in vitro cultures (c-e). Note that the direction of prospective extensions beyond the wound sites for the basal or the apical cultures will be basal-to-apical or apical-to-basal, respectively. c-e: both the basal (basal culture) and apical (apical culture) portions of the same cochlea (a-b) were cultured and extensions were monitored using the cutting wound sites (indicated by arrows) as reference points (c-e). Hair cells (GFP+) differentiated normally in the apical culture after 4 DIV (c). However, the rows of hair cells did not pass the bisection site (c), indicating no apical-to-basal extension in the apical culture. The rows of hair cells in the basal cultures (d and e) extended past the bisection sites (d, e) from basal-to-apical direction. No BrdU incorporation in the organ of Corti was detected in extended basal cultures (e). The rows of hair cells were bracketed with a pair of arrowheads, and the orientation of the explants was indicated in (c-e).The bottom panels (f-j) are corresponding phase images of the upper panels.

The in vivo and in vitro data together supported the hypothesis that the cells within the postmitotic precursor domain underwent cellular rearrangements for extension. The process appears to occur through thinning of the precursor domain, and this extension is unidirectional from the base to the apex along the longitudinal axis of the cochlea, parallel to the basal-to-apical differentiation gradient of the organ of Corti. The extension of the organ of Corti through narrowing cell layers at a perpendicular axis is characteristic of cell movements known as “convergent extension”6, a notion suggested by us4 and supported by a recent morphological study11. Significantly, convergent extension in vertebrates is regulated by a conserved genetic pathway, the PCP pathway, delineated by its role in planar cell polarity (PCP) in Drosophila12-15. In mice, mutations in homologous PCP genes, Vangl21,16, Celsr12,17-18, or both Dishevelled (Dvl) 1 and 219-20, lead to neural tube defects inferred to be failure of convergent extension21-24. In addition, loss-of-function of Vangl21 or Celsr12 also results in mis-orientation of stereocilia in the cochlea, implying that this putative mammalian PCP pathway regulates cell polarity as well. Therefore, we hypothesized that the mammalian PCP pathway regulates both the polarized extension and establishment of PCP in the organ of Corti during terminal differentiation.

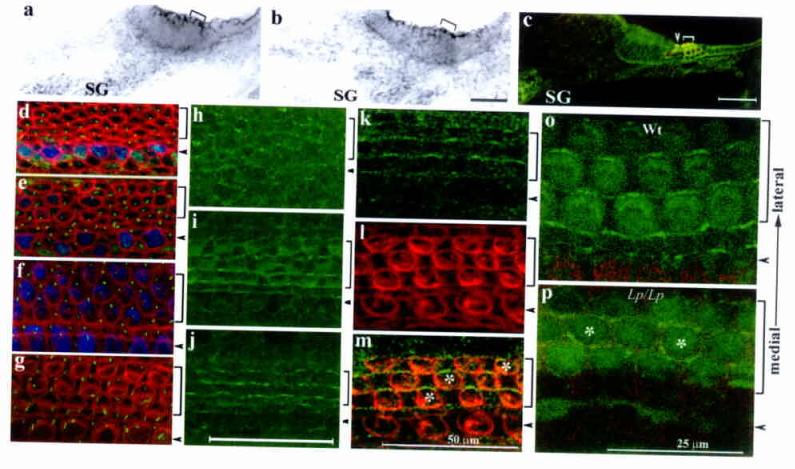

We analyzed the expression of mouse PCP homologous genes. As shown in figure 3, Celsr1 and Dvl1 are expressed in the epithelium and the spiral ganglion neurons (SG) that innervate the hair cells at E16.5 (Fig. 3a and 3b). In addition, mice with a BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome) transgene containing a functional Dvl2-EGFP fusion gene (supplemental Fig. 2) expressed DVL2-EGFP in the entire epithelium and the SG neurons in the cochlea (Fig. 3c). The expression of these three PCP homologous genes is similar to the reported expression of Vangl21. Furthermore, similar to the polarized subcellular distribution of PCP components in Drosophila7-8,14-15, DVL2-EGFP shows a polarized and asymmetric subcellular localization in the organ of Corti (Fig. 3h-j) consisting newly differentiated hair cells as well as in the regions that undergo hair cell differentiation at E17.5(Fig. 3d-j). Coimmunuostaining further revealed that DVL2-EGFP is enriched on the lateral side of the apical surface of the hair cells (Fig. 3k-m). This polarized distribution of DVL2-EGFP in both the newly differentiated and differentiating organ of Corti indicates that DVL2-EGFP is asymmetrically localized in the organ of Corti prior to and during establishment of stereocilia orientation. This polarized subcellular distribution of DVL2-EGFP in the hair cells was disrupted in Vangl2 loss-of-function mutant looptail (Lp/Lp) mice16 (Fig. 3p). In contrast to wild-type littermates of readily detectable polarized membrane enrichment (Fig. 3o) at E18.5 (Fig. 3k, 3o), the membrane enrichment of Dvl2-EGFP was greatly reduced in Lp/Lp mutants. Using laser powers 20 fold of that used for wild-type littermates, faint cortical signals of Dvl2-EGFP could be detected only sporadically, and were not restricted to the lateral side of hair cells (Fig. 3p). These data suggested that a mammalian PCP pathway, involving Vangl2, Dvl and Celsr1 genes, may share a similar underlying molecular mechanism with the fly PCP pathway in planar cell polarization.

Fig. 3.

Presence of a functional PCP pathway in the developing organ of Corti. a-c: in situ hybridization of Celsr1 (a) and Dvl1 (b) at E16.5, and DVL2-EGFP signals (c) at E18.5. The brackets in (a-b) indicate the organ of Corti. d-g: Confocal scans of the E17.5 organ of Corti at 80% (d), 75% (e), 50% (f), and 25% (g) from the base of the cochlear duct. At the base (g), hair cells are differentiated and stereocilia (red) are visible. In the medial region (f), the stereocilia are less developed and not visible (red). However, both inner and outer hair cells are differentiated (blue) and the kinocilia (green) are eccentric, indicating a polarized region. At the apical region (d-e), myosinVI expression (blue) has yet to complete in the outer hair cell region and the kinocilia (green) are centric, indicating a transition stage prior to the polarization process. h-m: Confocal scanning of DVL2-EGFP (green) in a whole mount organ of Corti at E17.5 from the corresponding apical (h), medial (i), and basal (j) regions as shown in d-g. Counter-staining with hair cell membrane (l, red) and DVL2-EGFP (k) at E18.5 indicated DVL2-EGFP signal at the lateral side of hair cells (m) o-p: DVL2-EGFP in wild-type (o) and Lp/Lp (p) littermates at E18.5. Note the loss of the wild-type (o) subcellular localization of DVL2-EGFP in the Lp/Lp mutant (p, the asterisks mark hair cells with DVL2-EGFP at the medial side). Arrowheads and brackets (c-p) mark the inner and outer hair cells, respectively. Scale: 50 μm (a-m).

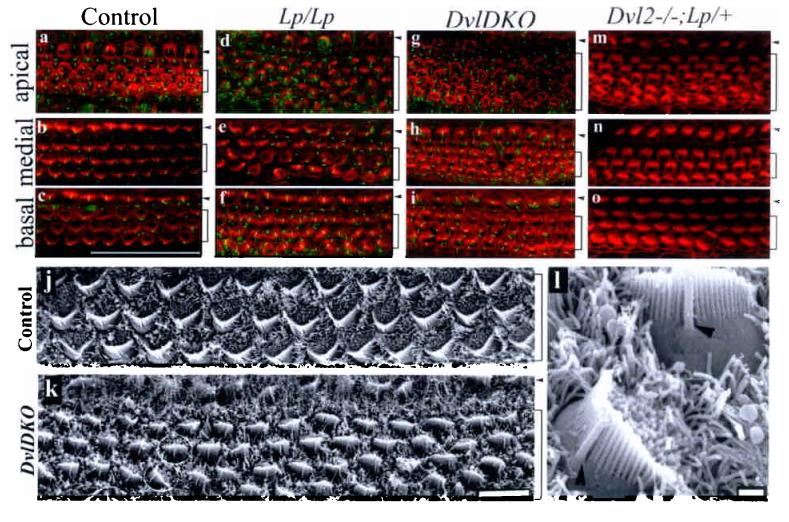

We next examined potential genetic interactions between Vangl2 and Dvl genes and the role for Dvl genes in the mammalian PCP pathway (Fig. 4 and 5). At E18.5 in Dvl119 or Dvl220 single null animals, or Dvl1 and Dvl2 double heterozygous, or Lp/+ animals display normal stereocilia orientation (Fig. 4 and data not shown). In contrast, Dvl1−/−; Dvl2−/− (DvlDKO)20, Lp/Lp, Dvl2−/−; Lp/+ animals show stereocilia mis-orientation (Fig. 4). As reported1, the development of the stereocilia in Lp/Lp (Fig. 4d-f) was comparable to the wild-type littermate while the uniform orientation of the stereocilia was disrupted (Fig. 4a-c). This disruption was more severe in the medial region than in the base. Similarly, stereociliary bundle misorientation in DvlDKO was mild in the base (Fig. 4i), but was more severely disrupted toward the medial region (Fig. 4h). Denser cellular packing and a less recognizable form of stereocilia by phalloidin staining in comparable regions from DvlDKO mutants were also observed (Fig. 4g-h). The misorientation of stereocilia in DvlDKO is apparent (∼35% in the two outer rows of outer hair cells), but to a less degree than in Lp/Lp mutants (∼95% in the two outer rows of outer hair cells) in comparable medial regions. These differences in DvlDKO from Lp/Lp mutants may result from additional cellular processes involving Dvl genes25-26 and the possible involvement of another mouse Dvl gene, Dvl327. Misorientation of stereociliary bundles were also seen in Dvl2−/−;Lp/+ mutants (Fig. 4m-o).

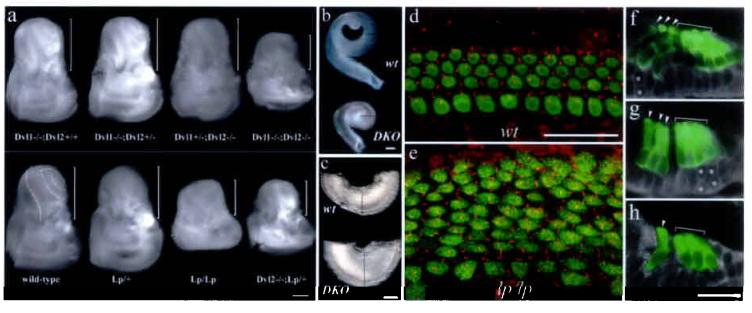

Fig. 4.

The stereocilia of the organ of Corti displayed abnormal polarity in Dvl1−/−;Dvl2−/− (DvlDKO), Lp/Lp, and Dvl2−/−;Lp/+ embryos. a-i: Confocal surface scanning of organs of Corti stained for stereocilia (red) and kinocilia (green) from E18.5 wild-type (a-c), Lp/Lp (d-f), DvlDKO(g-i) and Dvl2−/−; Lp/+ (m-o) embryos. Note that the stereocilia were readily stained in the basal and medial regions of the cochlea at this stage in the control (b-c), while they were less developed in the apical region (c). j-k: Scanning EM of the organs of Corti at comparable medial regions from E18.5 control Dvl1−/−;Dvl2+/− (j) and DvlDKO embryos (k). l: Higher magnification of SEM image for the two cells circled in (k). Note the relative positions of kinocilium (arrowhead) and stereocilia were maintained while the orientation of the stereocilia was altered in one of the cells. The outer and inner hair cell regions (a-k) are indicated by brackets and arrowheads, respectively. Scale bars: 50 μm (a-i); 10 μm (j and k); 952 nm (l).

Fig. 5.

Shortened and widened cochlear duct and its sensory organ, and defective extension in PCP mutants. a: inner ears from PCP mutants, DvlDKO, Lp/Lp, Dvl2−/−; Lp/+, and control embryos at E18.5. The brackets indicate the cochlea portion of the inner ear. The remainder is vestibule. Scale: 500 μm. b-c: dissected cochlear ducts (b) from a control (upper) and DvlDKO (lower) E18.5 embryos. Comparable regions from both samples were shown (c). The lines outline the diameters of the cochlear ducts at comparable regions (b and c). Scale: 200 μm. d-e: confocal images of the apical region of the organ of Corti from the control (d) and DvlDKO (e) E18.5 littermates. MyosinVI (green) for hair cells and acetylated α-tubulin (red) for kinocilia stainings were shown. Notice the organized patterning of both hair cells and kinocilia in the control samples (d) vs. increased hair cell rows and displacement of kinocilia in the mutant sample (e). Scale: 25 μm. f-h: overlays of myosin VI (green) and phase images of the organ of Corti at the apical-most (f), one fourth from the apex (g), and the basal-medial (h) regions of the cochlea from E18.5 DvlDKO mutants. The asterisks mark the cells that are yet to complete the thinning process. Scale: 25 μm.

Examination of these mutants further revealed a strong correlation between stereocilia orientation and the extension of the organ of Corti. Inner ears from PCP mutants of DvlDKO, Lp/Lp, and Dvl2−/−; Lp/+ animals have shortened and widened cochlear ducts (Supplemental Table I), compared with the normal appearance of inner ears from non-PCP control animals (Fig. 5a-c, i). The widened organ of Corti in PCP mutants (Fig. 5e, 4d, 4g, 4m) had increased rows of hair cells within about 1/3 of the cochlea from the apex, whereas compared to one row of inner and three rows of outer hair cells normally seen throughout the cochlea in control animals (Fig. 5d, comparable apical region). Collectively, these data indicate that Vangl2 and Dvl genes are both involved and interact genetically to regulate the length to width ratio of the cochlear duct, and that this phenotype associates with the PCP phenotype seen in the organ of Corti.

The organ of Corti in PCP mutants, Lp/Lp (data not shown) and DvlDKO (Fig.5f-h), underwent normal thinning to form one layer of hair cells and one layer of supporting cells in basal to medial regions along the cochlear duct (Fig. 5h). These observations imply that the integral cellular movements within the postmitotic precursor domain likely involve both radial (thinning) and medial-lateral (narrowing) intercalations6 (Supplemental Fig. 3). The shortened and widened cochlear ducts in PCP mutants are likely to be the manifestation of failed extension resulting from defective medial-lateral intercalation.

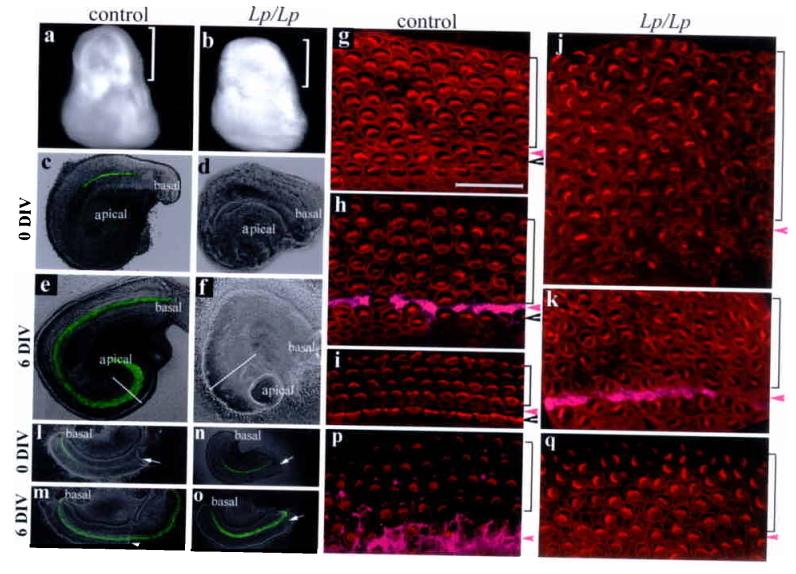

The anterior-posterior axis of the PCP mutants was shortened1-3 and the inner ears are displaced dorsally in the PCP mutants (data not shown). It is possible that the spatial alteration in PCP mutants limited the normal extension of the cochlear duct, thus affecting hair cell patterning and stereocilia orientation. We used intact and bisected cochlea organ cultures to test directly the correlation of the loss-of-function of the PCP pathway with stereocilia orientation and extension of the cochlea, respectively. Wild-type intact E14.5 cochlear ducts increased in length by 30% after 6 DIV (Fig. 6c and 6e), compared to a 2-fold growth in vivo. As a result, there were more rows of outer and inner hair cells toward the apical region (Fig. 6g-i), similar to what has been observed in other studies28. Nevertheless, the stereocilia polarity was maintained along the entire length of the cochlea duct (Fig. 6g-i), displaying a striking intrinsic fidelity of stereocilia orientation in wild type tissues. The organs of Corti from Lp/Lp embryos cultured under the same conditions failed to grow in length (< 2%) (Fig. 6d, 6f), and displayed misorientation of the stereocilia (Fig. 6j,k). The apex was widened noticeably in the culture (Fig. 6f). The extension retardation in PCP mutants was further directly demonstrated in bisected cultures (Fig. 6l-o). As expected (Fig. 2), extension proceeded in a basal-to-apical direction in wild-type (Fig. 6l-m, length increase = 1.74 ± 0.23 fold, n = 12) and Lp/+ bisected cultures (length increase = 1.61 ± 0.19, n = 4). The proper orientation of stereocilia was maintained in the extended organ of Corti (Fig. 6p). In contrast, the cochlea and its sensory organ from Lp/Lp littermates failed to grow comparably (Fig. 6n-o, length increase= 1.22 ± 0.08 fold, n = 7), and the orientation of stereocilia was disrupted (Fig. 6q). These data indicated that the misorientation of stereocilia was intrinsic to the Looptail mutation within the cochlear tissue, and that the Lp/Lp PCP mutants are defective in the extension of the cochlea and organ of Corti.

Fig. 6.

Direct requirement of PCP pathway in extension and planar cell polarity of the organ of Corti. a-b: inner ears from control and Lp/Lp littermates at E14.5. Brackets mark the cochlear portion of the inner ear. c-f: intact cochlear ducts from control (c and e) and Lp/Lp (d and f) cultured 6 DIV. Diameters of the cochlear ducts at the comparable apical regions were outlined (e and f). Hair cells were visualized by Math1-EGFP. g-k: confocal images stereocilia (phalloidin) for control (g-i) and Lp/Lp (j-k) cultures at the apical (g and j), medial (h and k), and basal (i) regions. Scale: 25 μm. l-q: bisected basal regions of the cochlear ducts from wild type (l-m) and Lp/Lp (n-o) cultured for 6 DIV, and the confocal images of stereocilia near the bisection sites for the wildtype (p) and Lp/Lp (q). Arrows in l-o indicate the bisection sites. Arrowheads and brackets in (g-k, p-q) mark the inner and outer hair cell regions, respectively, and magenta arrowheads mark the pillar cell region that was stained with p75 (h, k, p,magenta).

Our data demonstrate that the organ of Corti undergoes polarized extension characteristic of convergent extension through the thinning of cell layers during terminal differentiation. Analyses of PCP mutants further indicate that, in addition to regulating the planar cell polarity of the organ of Corti through a similar mechanism to its homologous Drosophila pathway by asymmetric distribution of PCP components7-8,14-16, the mammalian PCP pathway is also required for polarized extension of the cochlear duct and its sensory organ. The morphogenetic observations of the normal development of the organ of Corti and the defect in PCP mutants suggest that both radial and medial-lateral intercalations (yet to be tested directly) may be involved in the extension of the organ of Corti and that medial-lateral intercalation is significantly affected in PCP mutants. It is possible that the medial-lateral asymmetric subcellular localization of Dvl2 we observed may: (1) indicate a conserved cellular mechanism of PCP pathways from invertebrates to mammals in regulating planar cell polarity, and (2) underlie the cellular mechanism by which the vertebrate PCP pathway regulates convergent extension29 in the organ of Corti.

Methods

Mouse strains and animal care

The mouse strain Math1/GFP expressing GFP in the hair cells under the control of Math1 enhancers was as described4. Looptail animals were obtained originally from Jackson Laboratory. Dvl1 and Dvl2 double knockout (DvlDKO) alleles were generated as described19-20. Dvl2-EGFP animals were generated as described in supplemental figure 1.The mouse strain carrying Math1-RFP was generated by BAC-mediated transgenesis. Embryos positive for Math1/GFP or Math1-RFP were identified by positive GFP or RFP signals in the cerebellum and spinal cord, respectively. Genotyping for Dvl1, Dvl2 knockout alleles, and the Looptail allele was carried out as described16,19-20. To differentiate the Dvl2-EGFP BAC transgene from the endogenous wild-type Dvl2, a pair of primers flanking intron 2 were used for PCR (supplemental Table II). Endogenous wild-type Dvl2 allele gave rise to a PCR product of 370 bp, while the Dvl2-EGFP transgene, due to the insertion of the 34 bp LoxP site in intron 2, gave rise to a PCR product of 404 bp (supplementary Fig. 2). The targeted Dvl2 null allele would not be amplified in this PCR reaction. For BrdU injection, E14.5 timed pregnant females were injected with BrdU at 50 μg/gram of body weight three times at two hour intervals and sacrificed two hours after the last injection for pulse labeling, and three times per day at two hour intervals till E18.5 for chasing. Animal care and use was in accordance with NIH guidelines and was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University and University of California San Diego.

In situ hybridization and immunostaining of the inner ear tissues

Inner ear dissection, sectioning, immunostaining, and in situ hybridization were performed as described30. For analyzing planar cell polarity of the organ of Corti, whole mount organs of Corti were stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin, followed by incubation with Cy5-conjugated donkey against mouse antibody, counter stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, and visualized with Zeiss LSM510. To visualize native GFP signals in the ear from Dvl2-EGFP mice, the organs of Corti were dissected from lightly fixed embryos, counter stained with phalloidin, and images were acquired with Zeiss LSM510 for less than 1 μm optical sections. Primary antibodies and dyes used were: myosinVI (rabbit polyclonal, 1:200, from Tama Hasson in UCSD); BrdU (mouse monoclonal, 1:100, from Chemicon International Inc.); Islet1 (mouse monoclonal, 1:100, from Developmental Hybridoma Bank); ActCaspase3 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100, from R&D Systems); acetylated α-tubulin (monoclonal, 1:50, a gift from Winfield Sale at Emory University); p75 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100 from Chemicon International); rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (25 pM, from Molecular Probes). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes. cDNAs for Dvl1 and Celsr1 were cloned from theE15.5 inner ear epithelium by RT-PCR with oligos listed in supplemental table II. For quantification of misorientation of stereocilia, confocal images from kinocilium and stereocilium double staining were used according the method described1. Stereocilia with a larger than 20° deviation than normal were considered to be misoriented.

Hair cell count and cochlea length to width ratio (L/W) measurements

For L/W ratio, images of the entire dissected cochlear ducts were imported to NIH Image J, and calculated by three independent measurements for each sample. For hair cell counting, confocal images of the entire cochlear ducts stained for myosinVI were collected and hair cells were counted at least twice for each sample.

Inner ear Paint-fill

The embryos of appropriate stages were fixed in Bodian fixative for overnight at 4°C, dehydrated through series of alcohol, histo-cleared in methyl salicylate. The inner ears were then partially dissected to allow insertion of micropipettes filled with 1% white latex paint in methyl salicylate at the base of the cochlear duct for injection. Paint-filled inner ears were imaged with an Olympus stereoscope SZX12 fitted with Hamamatsu digital camera.

Organ culture

Timed-pregnant females were sacrificed at E14.5. Inner ears were dissected out in DPBS (GIBCO, Cat# 14040-133), incubated with dispase (GIBCO, Cat#17105-041, 1 mg/ml) and collagenase (Worthington, Cat# S3J6581, 0.5 mg/ml) in DPBS for 2 minutes at room temperature to clear away tissues surrounding the cochlear duct. Dissected cochlear ducts were allowed to settle down on polyD-lysine (Sigma, Cat# P-6407, 0.5 mg/ml) and fibronectin (Sigma, Cat# F1141, 0.005%) coated glass-bottomed dishes, and cultured in DMEM/F12 (Cellgro, Cat# 15-090-cv) supplemented with N2 (Gibco, Cat# 17502-048) for 4-6 DIV. For BrdU incorporation in the culture, 1 μM of BrdU was included in the culture media for the entire culture period. Culture media were replenished every other day, and images of live cultures were taken with an Olympus I71 inverted microscope or a Zeiss LSM510. For bisected cochlea cultures, while the base of the cochlear duct was adhered to the culture dish, the roof of the tubular cochlear duct that did not adhere to the dish remained at its original location during the culture period (supplemental Fig. 1). The bisection site of the roof of the cochlea, therefore, served as a reference marker for the extension of the organ of Corti in the culture, and verified by DiI labeling (supplemental Fig.1). For organ culture of Looptail mutants, the wild-type, Lp/+, or Lp/Lp littermates were initially identified by normal appearance, loop tail, or open neural tube, respectively. PCR reactions were followed to confirm the genotypes of the littermates. Culture images were imported into NIH Image J and the extension was quantified by comparing the original length of the cochlea duct to the final length after 4-6 DIV.

Scanning Electron Microscopy of the organ of Corti

Inner ears were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde (EM grade) for overnight at 4°C, transferred to 0.1M NaCacadylate, pH7.4. After removal of the aldehydes, the specimens were treated with 1% tannic acid, followed by osmium tetroxide treatment. Dehydrate the specimens through series ethanol, and critically dry the samples. The dried samples were mounted on metal stubs, and coated with gold particles, and ready for examination. The images were taken with DS-130/Schottky Field Emission SEM/STEM.

Database Accession Numbers

Vangl2/Ltap: Mm.36148; Celsr1: Mm.22680; Dvl1: Mm.3400; Dvl2: Mm.5114

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Moses, Winfield Sale, Barry Shur, and John Wallingford for help discussions during the project, and comments on the manuscript; David Martin and Teresa Etzel in Emory University, and Ella Kothari and Jun Zhao in the UCSD Cancer Center Transgenic Core for transgenic service; Doris Wu for technical advice on inner ear paint-fill; Robert Apkarian in Emory University EM Core for SEM; Jeff Saek for hair cell counting; Jane E. Johnson for Math1GFP animals; Winfield Sale for acetylated α-tubulin antibody; and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for Islet1 antibody. This work is supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (to A.C., X. L., A. W. B. and P.C.), and Woodruff Foundation (to X. L. and P.C.).

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to P.C. or A. W. B.

References

- 1.Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kelley MW. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature. 2003;423:173–177. doi: 10.1038/nature01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtin JA, Quint E, Tsipouri V, Arkell RM, Cattanach B, Copp AJ, Henderson DJ, Spurr N, Stanier P, Fisher EM, Nolan PM, Steel KP, Brown SD, Gray IC, Murdoch JN. Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu X, Borchers AG, Jolicoeur C, Rayburn H, Baker JC, Tessier-Lavigne M. PTK7/CCK-4 is a novel regulator of planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature. 2004;430:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature02677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen P, Johnson JE, Zoghbi HY, Segil N. The role of Math1 in inner ear development: Uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development. 2002;129:2495–2505. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis J, Davies A. Planar cell polarity in the inner ear: how do hair cells acquire their oriented structure? J Neurobiol. 2002;53:190–201. doi: 10.1002/neu.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller R. Shaping the vertebrate body plan by polarized embryonic cell movements. Science. 2002;298:1950–1954. doi: 10.1126/science.1079478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axelrod JD. Unipolar membrane association of Dishevelled mediates Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1182–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.890501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastock R, Strutt H, Strutt D. Strabismus is asymmetrically localized and binds to Prickle and Dishevelled during Drosophila planar polarity patterning. Development. 2003;130:3007–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruben RJ. Development of the inner ear of the mouse: a radioautographic study of terminal mitoses. Acta Otolaryngol. 1967;220(Supp):1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P, Segil N. p27(Kip1) links cell proliferation to morphogenesis in the developing organ of Corti. Development. 1999;126:1581–1590. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenzie E, Krupin A, Kelley MW. Cellular growth and rearrangement during the development of the mammalian organ of Corti. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:802–12. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinson CR, Adler PN. Directional non-cell autonomy and the transmission of polarity information by the frizzled gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:549–551. doi: 10.1038/329549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mlodzik M. Planar cell polarization: do the same mechanisms regulate Drosophila tissue polarity and vertebrate gastrulation? Trends Genet. 2002;18:564–571. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma D, Yang CH, McNeill H, Simon MA, Axelrod JD. Fidelity in planar cell polarity signalling. Nature. 2003;421:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature01366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tree DR, Ma D, Axelrod JD. A three-tiered mechanism for regulation of planar cell polarity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kibar Z, Vogan KJ, Groulx N, Justice MJ, Underhill DA, Gros P. Ltap, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Strabismus/Van Gogh, is altered in the mouse neural tube mutant Loop-tail. Nat Genet. 2001;28:251–255. doi: 10.1038/90081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chae J, Kim MJ, Goo JH, Collier S, Gubb D, Charlton J, Adler PN, Park WJ. The Drosophila tissue polarity gene starry night encodes a member of the protocadherin family. Development. 1999;126:5421–5429. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Usui T, Shima Y, Shimada Y, Hirano S, Burgess RW, Schwarz TL, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell. 1999;98:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lijam N, Paylor R, McDonald MP, Crawley JN, Deng CX, Herrup K, Stevens KE, Maccaferri G, McBain CJ, Sussman DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Social interaction and sensorimotor gating abnormalities in mice lacking Dvl1. Cell. 1997;90:895–905. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang J, Yang Y, Luo Z, Mei L, Chien KR, Sussman DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development. 2002;129:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darken RS, Scola AM, Rakeman AS, Das G, Mlodzik M, Wilson PA. The planar polarity gene strabismus regulates convergent extension movements in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2002;21:976–85. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goto T, Keller R. The planar cell polarity gene strabismus regulates convergence and extension and neural fold closure in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2002;247:165–81. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallingford JB, Rowning BA, Vogeli KM, Rothbacher U, Fraser SE, Harland RM. Dishevelled controls cell polarity during Xenopus gastrulation. Nature. 2000;405:81–85. doi: 10.1038/35011077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallingford JB, Harland RM. Neural tube closure requires Dishevelled-dependent convergent extension of the midline. Development. 2002;129:5815–25. doi: 10.1242/dev.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N. Differential recruitment of dishevelled provides signaling specificity in the planar cell polarity and wingless signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2610–2622. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutros M, Paricio N, Strutt DI, Mlodzik M. Dishevelled activates JNK and discriminates between JNK pathways in planar polarity and wingless signaling. Cell. 1998;94:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torban E, Wang HJ, Groulx N, Gros P. Independent mutations in mouse Vangl2 that cause neural tube defects in looptail mice impair interaction with members of the Dishevelled family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52703–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley MW, Xu XM, Wagner MA, Warchol ME, Corwin JT. The developing organ of Corti contains retinoic acid and forms supernumerary hair cells in response to exogenous retinoic acid in culture. Development. 1993;119:1041–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang D, Munro EM, Smith WC. Ascidian prickle regulates both mediolateral and anterior-posterior cell polarity of notochord cells. Curr Biol. 2005;15:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radde-Gallwitz K, Pan L, Gan L, Lin X, Segil N, Chen P. Expression of Islet 1 marks the sensory and neuronal lineages in the mammalian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 2004;477:412–421. doi: 10.1002/cne.20257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]