Abstract

GB virus B (GBV-B), which infects tamarins, is the virus most closely related to hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV has a protein (p7) that is believed to form an ion channel. It is critical for viability. In vitro studies suggest that GBV-B has an analogous but larger protein (p13). We found that substitutions of the −1 and/or −3 residues of the putative cleavage sites (amino acid 613/614 and 732/733) abolished processing in vitro and rendered an infectious GBV-B clone nonviable in tamarins. Internal cleavage was predicted at two sites (amino acid 669/670 and 681/682), and in vitro analysis indicated processing at both sites, suggesting that p13 is processed into two components (p6 and p7). Mutants with substitution at amino acid 669 or 681 were viable in vivo, but the recovered viruses had changes at amino acid 669 and 681, respectively, which restored cleavage. A mutant lacking amino acid 614–681 (p6 plus part of p7) was nonviable. However, a mutant lacking amino acid 614–669 (p6) produced high titer viremia and acute resolving hepatitis; viruses recovered from both animals lacked the deleted sequence and had no other mutations. Thus, p6 was dispensable but p7 was essential for infectivity. The availability of a recombinant GBV-B virus containing a p7 protein with similarities to the HCV p7 will enhance the relevance of this model and will be of importance for identifying compounds that inhibit p7 function as additional therapeutic agents.

Keywords: animal model, chronicity, ion channel

GB virus-B (GBV-B) causes acute resolving hepatitis in experimentally infected New World monkeys, including tamarins, marmosets and owl monkeys (1–7). Because GBV-B is phylogenetically the virus most closely related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) (3, 8, 9), experimental infection of New World monkeys with this virus might serve as a surrogate model for studies of HCV that have been possible only in chimpanzees (10). HCV has a small p7 protein, located between the E2 and NS2 proteins of the precursor polyprotein. The p7 protein crosses the endoplasmic reticulum membrane twice and has its N and C termini directed toward the lumen (11); it can assemble into an ion channel (12). Furthermore, the p7 protein is critical for infectivity of HCV (13), but it is not required for RNA replication (14).

Previously we reported that GBV-B has a 13-kDa protein, also located between E2 and NS2 of the precursor protein.§ Recently, Giboudo et al. (15) demonstrated that a p13 protein is released from the precursor protein of GBV-B by host signal peptidase cleavage at amino acid 613/614 and amino acid 732/733. The p13 protein was predicted to contain four transmembrane domains (TMD) with two cytoplasmic loops. In the current study, we mutated the putative cleavage sites of GBV-B p13 and determined the effect of these mutations on proteolytic processing in vitro and on infectivity in vivo. In addition, we analyzed the importance of positively charged amino acids found in the cytoplasmic loops. Finally, we generated a viable GBV-B genome that has a p7-like protein.

Results

Processing of the GBV-B p13 Protein and Its Importance for Infectivity in Vivo.

Studies by Ghibaudo et al. (15) demonstrated that a p13 protein is produced by cleavage in reticulocyte lysate at amino acid 613/614 and 732/733 of the GBV-B polyprotein, but the computer program signalp (16) predicts that additional cleavage by host peptidase could occur at amino acid 669/670 and 681/682 (Table 1), although the predicted value for cleavage at amino acid 669 is much lower than the values found for the three other sites. To determine whether these putative sites were cleaved, expression plasmids encoding amino acids 1–729 (to detect the C-terminal end of p13) and amino acids 439–939 (to detect the C-terminal end of NS2), respectively, of the wild-type GBV-B sequence were transfected into 293T cells and GBV-B protein was indirectly detected by Western blot with antibody to a V5-epitope tag fused at the C terminus.

Table 1.

Predicted cleavage sites and cleavability of wild-type GBV-B and mutants from E2 to NS2 protein

| Amino acids | Cleavage site aa | Y score (0–1) |

|---|---|---|

| 613/614 | ||

| Wild-type | ASG/Y | 0.680 |

| G613N | ASN/Y | 0.413 |

| 669/670 | ||

| Wild-type | AAG/L | 0.326 |

| G669N | AAN/L | 0.203 |

| G669S | AAS/L | 0.198 |

| 681/682 | ||

| Wild-type | AAA/Q | 0.696 |

| A681R | AAR/Q | 0.382 |

| A681C | AAC/Q | 0.506 |

| A680L | ALA/Q | 0.592 |

| 732/733 | ||

| Wild-type | ASA/F | 0.536 |

| A730N-A732R | NSR/F | 0.326 |

Signal peptidase cleavage sites and cleavability of wild-type GBV-B and mutants were predicted by using signalp 2.0. Cleavability at each site is shown as a Y score. Y score > 0.32 was considered to be significant.

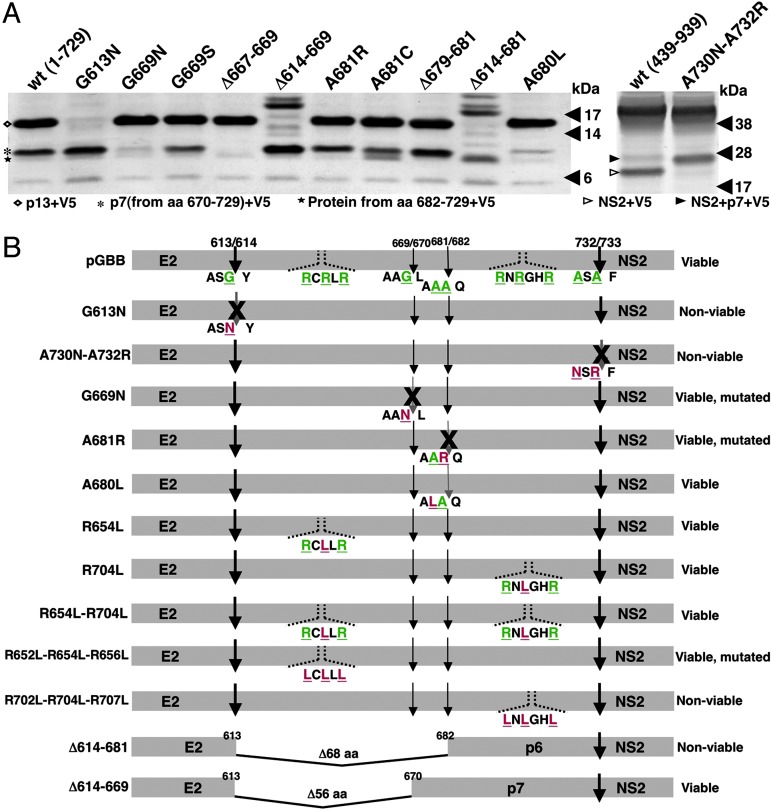

Mutants of GBV-B were analyzed in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1). After transient expression of amino acids 1–729 of GBV-B, we detected an ≈16 kDa protein by Western blot (predicted to be ≈13 kDa without V5-epitope tag), consistent with cleavage at amino acid 613/614 (Fig. 1A). After transient expression of amino acids 439–939 of GBV-B, we detected a ≈26-kDa protein, consistent with cleavage at amino acid 732 (Fig. 1A). Because it is well established that the −1 and −3 residues are of critical importance for signal peptidase cleavage, we next introduced mutations at the −1 and/or −3 positions in an attempt to abolish cleavage at amino acid 613/614 and 732/733, respectively (Table 1). Western blot analysis indicated that the G613N and A730N-A732R mutations severely diminished cleavage at amino acid 613/614 and 732/733, respectively (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the identical mutations were introduced into an infectious full-length GBV-B clone (pGBB) to test the effect of these mutations on infectivity (Fig. 1B). RNA transcripts from each mutant were tested in two tamarins (SM, Saguinus mystax). Both mutants were nonviable, because GBV-B RNA was not detected in the transfected animals during at least 25 weeks of followup. Thus, our data support the existence of a p13 protein and suggest that cleavage at amino acids 613 and 732 is required for in vivo infectivity of GBV-B.

Fig. 1.

In vitro and in vivo analysis of GBV-B p13 mutants. (A) In vitro analysis of GBV-B p13 processing by host signal peptidase. Approximately 48 h after transfection of 293T cells with pcDNA3.1_1-729V5 (A Left) and pcDNA_439–939V5 (A Right), cells were lysed, deglycosylated with PNGase F, and submitted to SDS/PAGE. (A Left) Western blot analysis of E2/p13 protein cleavage site (amino acid 613/614) and internal cleavage at amino acid 669/670 and amino acid 681/682. The positions of GBV-B proteins are indicated on the left [p13 (amino acids 614–729) +V5, diamond; p7 (amino acid 670–729) +V5, asterisk; amino acid 682–729 +V5, star]. The size (in kDa) of marker proteins is indicated on the right. (A Right) Western blot analysis of p13/NS2 protein cleavage site (amino acid 732/733). The positions of GBV-B proteins are indicated on the left (NS2, open arrowhead; NS2+p7, closed arrowhead). The size (in kDa) of marker proteins is indicated on the right. (B) RNA transcripts from each pGBB mutant were tested for infectivity by intrahepatic transfection in at least two tamarins. Viability is indicated on the right. Some mutants were viable, but the sequence recovered from transfected animals had acquired mutations that most likely represented compensating mutations. The amino acids that were mutated in pGBB are shown in green in the wild-type sequence; mutant sequences are shown in red.

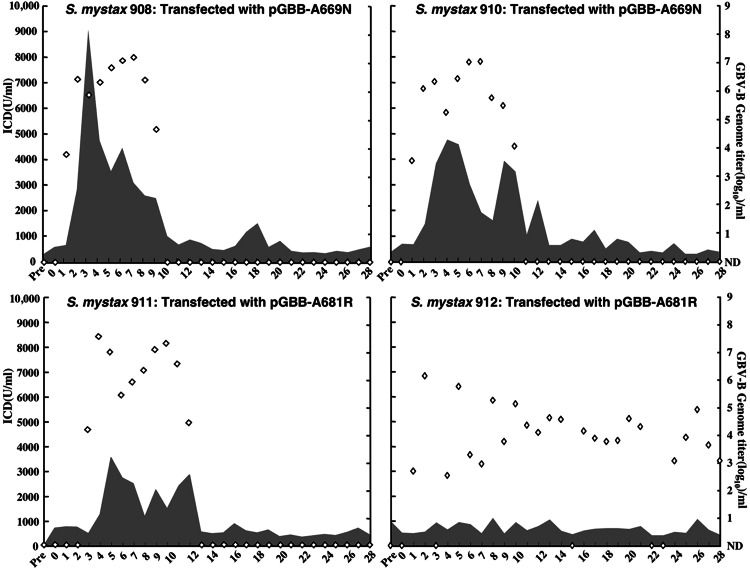

After expression of amino acids 1–729 of GBV-B in 293T cells, we consistently observed a ≈10-kDa protein (predicted to be ≈7 kDa without V5-epitope tag) and a faint ≈9 kDa protein (predicted to be ≈6 kDa without V5-epitope tag), suggesting that additional cleavage might occur in the middle of the p13 protein (Fig. 1A). These products could result from cleavage at 669/670 and 681/682, respectively, the two sites predicted by signalp program. We therefore introduced mutations at the −1 position in an attempt to diminish cleavability at these sites (Table 1). To minimize back mutation to the wild-type sequence, each introduced mutation was designed so that it would require at least two nucleotide changes to revert to the original amino acid. In Western blot analysis, the G669N mutation severely diminished cleavage and a mutant lacking amino acids 667–669 abolished cleavage at this site (Fig. 1A). In vivo, however, a virus containing the G669N mutation was infectious (Fig. 1B): both tamarins (SM908 and SM910) transfected with RNA transcripts from pGBB-G669N became viremic at week 1 and had peak RNA titers of ≈108 genome equivalents (GE)/ml (Fig. 2). Both animals developed acute hepatitis, and the infection was apparently resolved in both animals. The genome (corresponding to nucleotides 36–9,107 of pGBB, including the entire ORF) of the virus recovered from both animals, at week 5, was sequenced and revealed a single nucleotide change, which resulted in a change of the mutant amino acid N (codon: AAT) to S (codon: AGT) at amino acid 669. Although this change did not increase the predicted cleavage value (Table 1), it fully restored cleavage in vitro (Fig. 1A). Therefore, although cleavage at this site must be considered provisional until it is confirmed by protein sequencing or by other methods, our data indicate that cleavage at this site is critical for productive GBV-B infection.

Fig. 2.

Course of GBV-B infection in 4 SM tamarins after intrahepatic transfection with RNA transcripts of pGBB-G669N (SM908 and SM910) and pGBB-A681R (SM911 and SM912). Serum levels of isocitrate dehydrogenase [ICD (units/ml); shaded area] and the estimated log10 GBV-B GE titer per ml, determined in a TaqMan assay (diamonds), were plotted against time. Samples found to be below the assay cutoff of 103 GE/ml in the TaqMan assay are shown as not detected (ND).

Because amino acid 669/670 is predicted to be located in the second transmembrane domain of p13 (15), we speculated that it might not be cleaved by host signal peptidase. Recently, a presenilin-related aspartic protease, signal peptide peptidase (SPP), was identified (17). SPP is an intramembrane-cleaving protease identified by its cleavage of several type II membrane signal peptides after signal peptidase cleavage. The chemical compound (Z-LL)2-keton inhibits processing of signal peptides by SPP. Therefore, we performed protein expression in the presence of (Z-LL)2-keton. However, this inhibitor did not cause a loss of internal cleavage in the p13 protein (data not shown), suggesting that the cleavage at amino acid 669/670 probably is also catalyzed by host signal peptidase.

Ghibaudo et al. (15) reported that they found no evidence of cleavage at amino acid 681/682 in in vitro translation experiments. However, the 9-kDa protein observed after expression of amino acids 1–729 of GBV-B in our study (indicated by a star in Fig. 1A) could result from cleavage at amino acid 681/682, and in Western blot analysis, the A681R mutant did appear to produce less of this protein (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, a mutant lacking amino acids 679–681 prevented production of this cleavage product (Fig. 1A). In vivo, the A681R substitution mutant was infectious (Fig. 1B): SM911 and SM912 transfected with pGBB-A681R became viremic at week 3 and 2, respectively, and had peak RNA titers of ≈107.5 GE/ml and 106 GE/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). Both animals developed acute hepatitis, and the infection was apparently resolved in one animal (SM911) but persisted in the other animal (SM912). The genome (corresponding to nucleotides 36–9,107 of pGBB) of virus recovered from both animals (SM911, week 5; SM912, week 2) contained a change of the mutant amino acid R (codon: CGT) to C (codon: TGT) at amino acid 681. This change significantly increased the predicted cleavage value at amino acid 681/682 (Table 1) and clearly increased cleavability in vitro (Fig. 1A). Finally we introduced a mutation at the −2 position, which was predicted not to affect the cleavability at 681/682 (Table 1). As expected, the A680L mutant did not appear to influence cleavage at amino acid 681/682, but to our surprise, it did appear to diminish the product resulting from cleavage at amino acid 669/670 in vitro (Fig. 1A); this result could either be due to an effect on cleavage or stability of the product containing this substitution. However, this mutant was fully viable in vivo (Fig. 1B) and produced a wild-type infection in both transfected animals (SM918 and SM919, data not shown). Furthermore, the genome (corresponding to nucleotides 36–9,107 of pGBB) of viruses recovered from each animal, at weeks 2 and 3, respectively, retained the A680L mutation and did not contain compensating mutations. Overall, these data suggest that processing at amino acid 681/682 might also play a role in viability of GBV-B.

Importance of Positively Charged Amino Acids in the Cytoplasmic Loops of the GBV-B p13 Protein.

The cytoplasmic loop of the p7 protein of HCV has two positively charged amino acids that are indispensable for infection of chimpanzees (13). Computer analysis predicts that the p13 protein of GBV-B has two cytoplasmic loops, one in each cleavage product (15). Each of these loops contains three positively charged amino acids (R) so we investigated whether these residues are analogous to those in HCV and are important for infectivity of GBV-B. First we substituted an L (codon: TTG) for the middle R residue in the loop of either or both cleavage products (Fig. 1B). RNA transcripts from each mutant were tested in two tamarins each; pGBB-R654L in SM923 and SM924, pGBB-R704L in SM920 and SM922, and pGBB-R654L-R704 in SM916 and SM917. All six animals developed wild-type-like GBV-B infection (data not shown). Furthermore, the genome of viruses recovered from SM923, SM920, SM916, and SM917 at week 2 retained the sequence of the transfected RNA, indicating that neither of the mutations was detrimental.

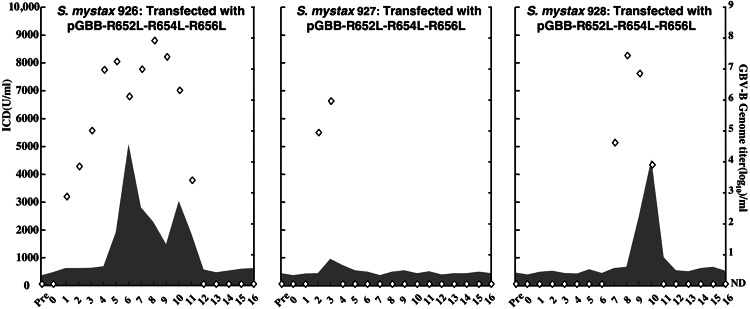

Next, we inoculated four tamarins with the mutant pGBB-R652L-R654L-R656L, which has substitutions of all three R residues in the loop within the N-terminal cleavage product (Fig. 1B). One animal (SM925) was not infected. The other three animals (SM926, SM927, and SM928) were infected, but the course of infection was highly attenuated in two (SM927 and SM928) (Fig. 3). In all three animals, the genome of viruses recovered at weeks 3 and 8 (SM926), week 3 (SM927), and week 8 (SM928) had maintained all three L substitutions at amino acids 652, 654, and 656. In SM926, we detected no other changes at week 3, but at week 8, we did detect two mutations that resulted in F646S and N703D amino acid changes. The former might be an adaptive mutation; the latter is seen also in animals infected with other GBV-B viruses (ref. 18; data not shown). There were no changes in the virus recovered from SM927. In SM928, we detected three mutations, two were silent and one resulted in an amino acid substitution, L651P, which most likely is an adaptive mutation. Overall, the substitutions of the positively charged amino acids in the cytoplasmic loop of the N-terminal cleavage product did appear to influence GBV-B infection, but they were not lethal mutations.

Fig. 3.

Course of GBV-B infection in three SM tamarins after intrahepatic transfection with RNA transcripts of pGBB-R652L-R654L-R656L. See also Fig. 2 legend.

In contrast, substitutions of the three R residues in the loop of the C-terminal cleavage product were lethal. RNA transcripts from the mutant pGBB-R702L-R704L-R707L were nonviable; GBV-B RNA was not detected during 20 weeks of followup in either of the two transfected tamarins.

A Deletion Mutant Containing only the C-Terminal Cleavage Product of GBV p13 Is Fully Functional in Vivo.

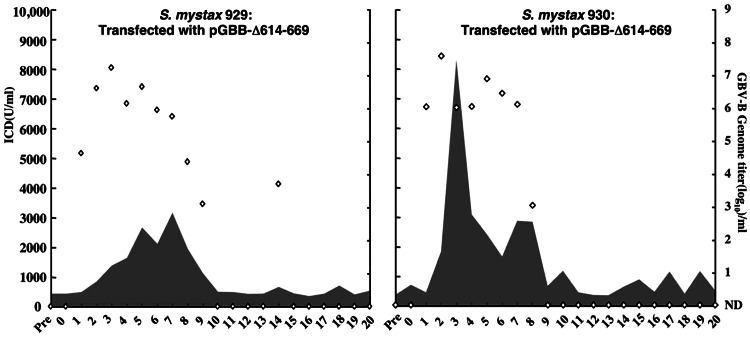

Because mutations in the cytoplasmic loop within the C-terminal cleavage product of the p13 protein rendered GBV-B noninfectious, whereas similar mutations in the loop within the N-terminal cleavage product permitted GBV-B infection, we speculated that the N-terminal component might be dispensable. If so, deletion of the N-terminal cleavage product should not prevent infection of tamarins. However, because it appeared that the p13 protein could be processed into components by cleavage at two different sites (at amino acid 669/670 and/or 681/682), it was not clear where the boundaries should be. Therefore, we first transfected two animals with RNA transcripts from a mutant lacking the first 68 amino acids of p13 (amino acids 614–681) (pGBB-Δ614–681). However, this mutant was not viable (Fig. 1B). The E2 C-terminal junction of the mutant was apparently processed appropriately, because a 9-kDa cleavage product was released (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we transfected the same two animals (SM929 and SM930) with a mutant containing a smaller deletion (amino acids 614–669) (pGBB-Δ614–669), predicted by the cleavage at 669/670 (Fig. 1B). In this case, both animals developed a wild-type infection with early appearance of high viral titers and with severe hepatitis in one animal (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the genomes (corresponding to nucleotides 36–9107 of pGBB) of viruses recovered from each animal at peak viral titer (SM929, weeks 1 and 3; SM930, weeks 1 and 2) lacked amino acid 614–669 and had no other changes. Thus, this GBV-B deletion mutant, in which the p13 protein of 119 amino acids was truncated to a p7 protein of 63 amino acids, was fully viable in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Course of GBV-B infection in two SM tamarins after intrahepatic transfection with RNA transcripts of pGBB-Δ614–669. See also Fig. 2 legend.

Chimeric GBV-B Encoding HCV p7 Protein Instead of GBV-B p13 Is Nonviable.

Because our data revealed that GBV-B is fully functional with a p7 protein that is similar to the HCV p7 in length, topology, and even in its amino acid sequence, we tested the chimera pGBB-H77p7, which has a HCV p7 gene from strain H77 (19) instead of an authentic GBV-B p13 gene, for infectivity. GBV-B RNA was not detected during 16 weeks of followup in either of the two transfected tamarins.

Discussion

GBV-B causes acute resolving hepatitis in experimentally infected New World monkeys. Furthermore, this orphan virus is the agent most closely related to HCV, a virus that causes very significant chronic liver disease in humans. It was previously demonstrated that the HCV p7 protein is critical for infectivity in vivo, although it is not required for RNA replication in vitro (13). Recently, we demonstrated that the p7 protein is also critical for infectivity of HCV in Huh-7 cells (unpublished data) by using the JFH1 cell culture system (20). Also it was found that the p7 protein of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), another member of the virus family Flaviviridae, is necessary for generation of infectious virions in cell culture (21). However, the detailed function of the HCV and BVDV p7 proteins in the viral life cycle remains to be determined. Surprisingly, GBV-B was found to have a p13 protein instead of a p7 protein (15). However, in the present study, we have demonstrated that the N-terminal 56 amino acids of p13 (amino acid 614–669; p6 protein) are not required for GBV-B infection and that a virus with a p7 protein (amino acids 670–732), like HCV and BVDV, is fully functional in vivo. The availability of a recombinant GBV-B virus with a p7 protein with many similarities to the HCV p7 will enhance the relevance of this surrogate model in the study of this unique protein in vivo and in vitro.

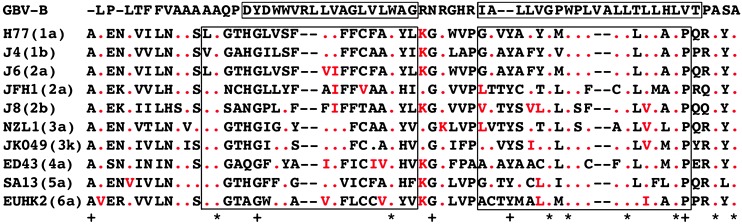

The p7 protein of GBV-B (amino acids 670–732) shares many similarities with the HCV p7 protein (Fig. 5). They are both 63 amino acids in length. Both consist of a long N-terminal luminal tail and a short C-terminal luminal tail. Each protein has two transmembrane domains connected by a cytoplasmic loop. The cytoplasmic loop contains three and two positively charged amino acids, respectively, in GBV-B and HCV. The BVDV p7 protein also resembles these structures (21). In HCV and BVDV, it was demonstrated that the charged residues are important for infectivity, probably because these charges contribute to maintaining the membrane topology of the p7 protein (13, 21). Similarly we found that a GBV-B mutant with L substitutions at all three R residues in the cytoplasmic loop within the putative p7 protein was nonviable in vivo. These substitutions did alter the predicted topology (data not shown). In contrast, a substitution of the middle R residue alone, which did not alter the predicted topology, was fully viable in vivo. Thus, the structure of the p7 protein of GBV-B also appears to be critical for infectivity.

Fig. 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of GBV-B and HCV p7 proteins by the clustalw (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw) program. Boxed amino acids represent those predicted to comprise transmembrane domains of GBV-B (15) and HCV (11). Red dots show amino acids identical to those in the GBV-B sequence; highly conserved amino acids [hydrophobic and aliphatic (L, I, and V) or positively charged (R, K, and H)], compared with the analogous GBV-B amino acids, are also highlighted in red. A star indicates that the GBV-B and HCV sequences at that position are identical; a plus sign indicates that they are identical only among the HCV isolates.

We cannot rule out that the p13 protein of GBV-B has an independent function. However, the GBV-B virus with only the p7 protein replicated at high viral titers in transfected tamarins and caused severe hepatitis. Also, it is not clear whether the N-terminal 56 amino acids (amino acids 614–669; p6 protein) play a role in the GBV-B life cycle. The robust replication of the p7 recombinant virus in vivo could suggest that amino acids 614–669 has a negative effect on translation or replication in the viral life cycle. On the other hand, the fact that viruses with L substitutions of the R residues in the cytoplasmic loop within this N-terminal cleavage product were attenuated in vivo and acquired compensating mutations suggests that this protein in the context of the wild-type p13 protein has a function. One possibility is that GBV-B p13 can form a heteromer arising from the N-terminal (amino acids 614–669) and C-terminal (670–732) subunits, whereas in the p7 mutant, the ability to form a homomer is maintained. But it is more likely that the p7 protein functions alone as the unit equivalent to the HCV and BVDV p7 proteins.

The HCV p7 protein, which penetrates the membrane twice, was suggested to be an ion channel (12) and, thus, to belong to a group of small proteins named viroporins. Generally, the viral ion channels are thought to penetrate the membrane only once as a single α-helix. However, picornavirus (e.g., poliovirus, coxsackievirus, and rhinovirus) 2B proteins, which may be viroporins, are also predicted to comprise two transmembrane domains connected with 5 amino acids containing at least one arginine (22). Thus, the GBV-B p7 protein might also be a viroporin. The best characterized virus ion channels are M2 from influenza, Vpu from HIV, and 6k from alphavirus. M2 is considered to be a homotetramic proton channel, which is responsible for the uncoating of the virion in the early endosome and mediates transport of viral proteins through the excretory pathway in the late phase of infection (23, 24). Vpu seems likely to form a homopentamer and to play a role in virus budding through an effect on the cellular environment, indirectly enhancing Gag trafficking to the plasma membrane (25, 26). The alphavirus 6k protein has several functions: It participates in viral protein trafficking by forming a complex with E1 and p62 (precursor of E2 and E3) and enhances membrane permeability (27–29). It has been shown that Vpu protein affects Sindbis virus glycoprotein processing and restores membrane permeabilization in a Sindbis 6k-deletion mutant (30). In addition, Vpu enhances the release of capsid protein of widely divergent non-HIV-1 retroviruses (25). The p7 proteins of GBV and HCV are most likely necessary for virus particle assembly or budding as shown for BVDV p7, which has similar topology (21). Additional studies are required to determine whether GBV-B p7 protein can function as an ion channel.

Our first attempt to construct a viable GBV-B chimera containing the heterologous HCV p7 was unsuccessful, suggesting that the HCV p7 protein either was not processed appropriately in this context or that there are more complicated functions that are involved in addition to formation of an ion channel (13). Our finding is not surprising, because we previously found that the HCV p7 gene from a 1a genome could not be substituted for p7 of a 2a genome (13). However, given the similarity of the GBV-B p7 to the HCV p7 protein, including several identical or similar amino acids (Fig. 5; ref. 15), studies of the GBV-B p7 may shed light on the function of the HCV p7 protein and might facilitate the generation of a viable chimeric HCV/GBV-B virus. Given that the p7 protein may function as an ion channel, it is an attractive target for development of new antiviral drugs, and recombinant GBV-B p7 viruses could become valuable tools for the evaluation of antiviral candidates in small primate animal models.

Materials and Methods

In Vitro Analysis of GBV-B Processing in Mammalian Cells.

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in complete DMEM (GIBCO/BRL) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS/4 mM l-glutamine/50 units/ml penicillin G/50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Because antibodies against GBV-B p13 or NS2 proteins were not available, the C terminus of GBV-B-expressed proteins was fused with a V5-epitope tag to permit detection. The GBV-B sequence encoding amino acids 1–729 (core through p13) or amino acids 439–939 (E2–NS2) was amplified from an infectious clone of GBV-B (pGBB) (3) by using standard techniques and inserted into the pcDNA3.1D/V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. This vector also contains a promoter for T7 RNA polymerase. The pcDNA3.1_1-729V5/His was used to analyze the cleavage between E2 and p13 as well as internal p13 cleavages. The pcDNA3.1_439-939V5/His was used to analyze the cleavage between p13 and NS2. Standard PCR mutagenesis techniques were used to introduce the desired mutations and the mutated sequence was inserted into pcDNA3.1_1-729V5/His at the EcoRI and FseI sites, or into pcDNA3.1_439-939V5/His at the EcoRI and AflII sites. The sequence of each expression vector was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis of the GBV-B insert.

Proteins were expressed in 293T cells (6 × 105 cells in a 35-mm-diameter plate) transfected with 1.0 μg of plasmids in the presence of Trans IT-LT1 (Mirus, Madison, WI) and Opti-MEM (GIBCO/BRL) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The expression level of GBV-B proteins under these conditions was very low (data not shown). Therefore, after overnight incubation, T7 vaccinia virus recombinant (kindly provided by Bernard Moss, National Institutes of Health) was inoculated into the cells to provide T7 RNA polymerase, and the cultures were gently rocked every 5 min for 1 h. Expression of the GBV proteins was analyzed by Western blot analysis after deglycosylation. Briefly, the cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed with denaturing buffer, then deglycosylated with PNGase F (New England Biolabs) in the presence of 1% Nonidet P-40 and G7 buffer at 37°C for 1 h.

For Western blot analysis, expressed proteins were fractionated on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel and electrically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 30 mA (constant) for 2 h in transfer buffer (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (100 mM Tris·HCl/150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 overnight and then incubated with a primary anti-V5-epitope mouse antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C. The membranes were washed three times in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody (Pierce). Membranes were washed three times and immune complexes were detected by reaction with NBT/BCIP reagent (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of GBV-B Mutants in Vivo.

To generate full-length GBV-B variants, the mutated p13 of the various expression vectors described above was substituted for the corresponding sequence of pGBB at the EcoRI and FseI sites (1–729 vector) or at the EcoRI and AflII sites (439–939 vector). Each pGBB mutant was transformed into DH5α competent cells (GIBCO/BRL). A single clone was selected and amplified in LB liquid cultures at 30°C for 18–20 h (3). Large-scale preparation of plasmid DNA was performed with a Qiagen (Valencia, CA) plasmid Endofree Maxi kit as described in refs. 3 and 18. The authenticity of each clone was confirmed by sequence analysis of the entire GBV-B sequence.

RNA transcription was performed as reported in refs. 3 and 18. Briefly, the cDNA clones were linearized with XhoI, purified, and 10 μg of linearized plasmid was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). The integrity of the RNA was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. Each transcription mixture was diluted with 400 μl of ice-cold PBS without calcium or magnesium and then immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C for a maximum of 24 h. Two transcription mixtures each were injected into the liver of a tamarin (SM) by a percutaneous inoculation guided by ultrasound (3, 18). Each mutant was tested in two or more animals. Animals were maintained under conditions that met or exceeded all requirements for their use in an approved facility.

Serum samples were collected weekly from the tamarins and monitored for liver enzyme levels (alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase, and isocitrate dehydrogenase) by standard methods. In addition, serum samples were tested for GBV-B RNA by real-time PCR as described in ref. 18. This test has a lower detection limit of 103 GE/ml, and results correlated very well with those from a nested RT-PCR assay (ref. 18; J.B., unpublished data). The nested RT-PCR was, therefore, performed only on selected samples in the present study to confirm GBV-B RNA negativity. The consensus genome sequence spanning nucleotides 36–9,107 of GBV-B viruses recovered from serum of infected animals was determined by direct sequencing of RT-PCR amplicons as described in detail in ref. 18. There is no standardized test for detecting antibodies to GBV-B.

Computer Analysis.

Host signal peptide cleavage sites within GBV-B and the effect of substitutions introduced at the -1, -2, and/or -3 positions were predicted with the signalp program (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-2.0) (16). The structure of GBV-B p13 and of mutants with substitutions of R residues within the cytoplasmic loops was predicted with the program tmhmm (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Charlene Shaver (Bioqual, Inc.) for excellent animal care and Dr. Bernard Moss for providing the T7 vaccinia virus recombinant. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- BVDV

bovine viral diarrhea virus

- GBV-B

GB virus B

- GE

genome equivalents

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SM

Saguinus mystax.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Takikawa, S., Bukh, J., Meunier, J.-C., Engle, R. E., Emerson, S. U. & Purcell, R. H., 10th International Meeting on HCV and Related Viruses, Dec. 2–6, 2003, Kyoto, p. 222.

References

- 1.Bright H., Carroll A. R., Watts P. A., Fenton R. J. J. Virol. 2004;78:2062–2071. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.2062-2071.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukh J., Apgar C. L., Govindarajan S., Purcell R. H. J. Med. Virol. 2001;65:694–697. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukh J., Apgar C. L., Yanagi M. Virology. 1999;262:470–478. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob J. R., Lin K. C., Tennant B. C., Mansfield K. G. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;85:2525–2533. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyuregyan K. K., Poleschuk V. F., Zamyatina N. A., Isaeva O. V., Michailov M. I., Ross S., Bukh J., Roggendorf M., Viazov S. Virus Res. 2005;114:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanford R. E., Chavez D., Notvall L., Brasky K. M. Virology. 2003;311:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simons J. N., Leary T. P., Dawson G. J., Pilot-Matias T. J., Muerhoff A. S., Schlauder G. G., Desai S. M., Mushahwar I. K. Nat. Med. 1995;1:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muerhoff A. S., Leary T. P., Simons J. N., Pilot-Matias T. J., Dawson G. J., Erker J. C., Chalmers M. L., Schlauder G. G., Desai S. M., Mushahwar I. K. J. Virol. 1995;69:5621–5630. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5621-5630.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons J. N., Pilot-Matias T. J., Leary T. P., Dawson G. J., Desai S. M., Schlauder G. G., Muerhoff A. S., Erker J. C., Buijk S. L., Chalmers M. L., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3401–3405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukh J. Hepatology. 2004;39:1469–1475. doi: 10.1002/hep.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrere-Kremer S., Montpellier-Pala C., Cocquerel L., Wychowski C., Penin F., Dubuisson J. J. Virol. 2002;76:3720–3730. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3720-3730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin S. D., Beales L. P., Clarke D. S., Worsfold O., Evans S. D., Jaeger J., Harris M. P., Rowlands D. J. FEBS Lett. 2003;535:34–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai A., St. Claire M., Faulk K., Govindarajan S., Emerson S. U., Purcell R. H., Bukh J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11646–11651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834545100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohmann V., Korner F., Koch J., Herian U., Theilmann L., Bartenschlager R. Science. 1999;285:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghibaudo D., Cohen L., Penin F., Martin A. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24965–24975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen H., Engelbrecht J., Brunak S., von Heijne G. Int. J. Neural Syst. 1997;8:581–599. doi: 10.1142/s0129065797000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weihofen A., Binns K., Lemberg M. K., Ashman K., Martoglio B. Science. 2002;296:2215–2218. doi: 10.1126/science.1070925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam J. H., Faulk K., Engle R. E., Govindarajan S., St. Claire M., Bukh J. J. Virol. 2004;78:9389–9399. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9389-9399.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagi M., Purcell R. H., Emerson S. U., Bukh J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8738–8743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakita T., Pietschmann T., Kato T., Date T., Miyamoto M., Zhao Z., Murthy K., Habermann A., Krausslich H. G., Mizokami M., et al. Nat. Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada T., Tautz N., Thiel H. J. J. Virol. 2000;74:9498–9506. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9498-9506.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieva J. L., Agirre A., Nir S., Carrasco L. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mould J. A., Drury J. E., Frings S. M., Kaupp U. B., Pekosz A., Lamb R. A., Pinto L. H. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31038–31050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakaguchi T., Leser G. P., Lamb R. A. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:733–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlinger H. G., Dorfman T., Cohen E. A., Haseltine W. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:7381–7385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schubert U., Ferrer-Montiel A. V., Oblatt-Montal M., Henklein P., Strebel K., Montal M. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:12–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liljestrom P., Lusa S., Huylebroeck D., Garoff H. J. Virol. 1991;65:4107–4113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4107-4113.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lusa S., Garoff H., Liljestrom P. Virology. 1991;185:843–846. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90556-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz M. A., Perez L., Carrasco L. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:12106–12110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez M. E., Carrasco L. Virology. 2001;279:201–209. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]