Abstract

Background: There is a broad need to improve physician continuing medical education (CME) in the management of intimate partner violence (IPV). However, there are only a few examples of successful IPV CME programs and none of these are suitable for widespread distribution.

Design: Randomized, controlled trial beginning in September 2003 and ending November 2004. Data were analyzed in 2005.

Setting/Participants: Fifty-two primary care physicians in small (< 8 physicians), community-based medical offices in Arizona and Missouri.

Intervention: Twenty-three physicians completed a minimum of 4 hours of an asynchronous, multimedia, interactive, case-based, online CME program, which provided them flexibility in constructing their educational experience (“constructivism”). Control physicians received no CME.

Main Outcome Measures: Scores on a standardized 10-scale self-reported survey of IPV knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported behaviors (KABB) administered prior to randomization and repeated at 6 and 12 months following the CME program.

Results: Use of the online CME program was associated with a significant improvement in eight of 10 KABB outcomes, including physician self-efficacy and reported IPV management practices, over the study period. These measures did not improve in the control group.

Conclusion: The Internet-based CME program was clearly effective in improving long-term individual educational outcomes, including self-reported IPV practices. This type of CME may be an effective and less costly alternative to live IPV training sessions and workshops.

BACKGROUND

Intimate partner (domestic) violence (IPV), is a common problem seen in medical practice,1-3 one that physicians have historically handled poorly, and one for which there have been longstanding calls for better education.4-7 Responding to these calls, medical organizations have developed workshop-based education programs designed to improve practicing physicians' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (KABB) in dealing with IPV. Combined with other systems-based interventions, such programs have been associated with improvements in KABB as well as increases in IPV screening rates, documentation, and referrals.8,9

Although live IPV workshops appear to improve important educational outcomes, they are expensive to produce and do not lend themselves to widespread distribution. IPV educational programs that can be easily distributed, such as group lectures, monographs, and journal articles, on the other hand, are unlikely to be effective.10 Thus, while there is an increasing recognition and requirement for IPV education, there continues to be a lack of effective mass distribution programs to meet this need.11

Internet-based (online) continuing medical education (CME) may provide a powerful option for improving IPV education. There is a growing use of online CME by practicing physicians, notably women and younger physicians,12 two groups that may have a particular interest in IPV. A recent study reported that an interactive online CME program produced changes in knowledge and performance in lipid screening and treatment that were comparable or superior to those produced by a live interactive workshop.13 There is evidence that online, case-based, IPV CME programs can improve short-term educational outcomes as effectively as multi-day live workshops.14 Thus, there is a need to determine whether well-designed online IPV CME programs can lead to durable improvements in IPV educational outcomes and provide the type of cost-effective, easily distributed, educational solutions needed to improve the medical management of IPV.

METHODS

Study Design

This study evaluated the effectiveness of an online IPV program in a community practice setting. The study used a pre-test/post-test design, comparing changes in baseline measures of physician IPV KABB at 6 and 12 months, between physicians who completed the online IPV program and physicians not assigned to take the program. The primary study hypothesis was that there would be significantly greater improvement at 6 and 12 months in IPV KABB scores in physicians completing the online CME versus physicians not assigned to take the program.

Participants

Community physicians in the specialties of internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and psychiatry in Kansas City and Phoenix were recruited to participate in a study of online IPV CME. Local medical societies, direct mail, IPV advocacy groups, and an independent practice association assisted with recruitment. There were approximately 6000 physicians in the appropriate specialties in the two cities. Participants were offered $25 for completing each of three paper-based IPV surveys. Physicians selected to take the online CME program were also offered 4 to 16 hours of free CME credit and a $75 honorarium. To be eligible for the study, physicians had to be in private (non-university, nongovernment) practice in the appropriate medical specialty, in a group of seven or fewer physicians, and have Internet access.

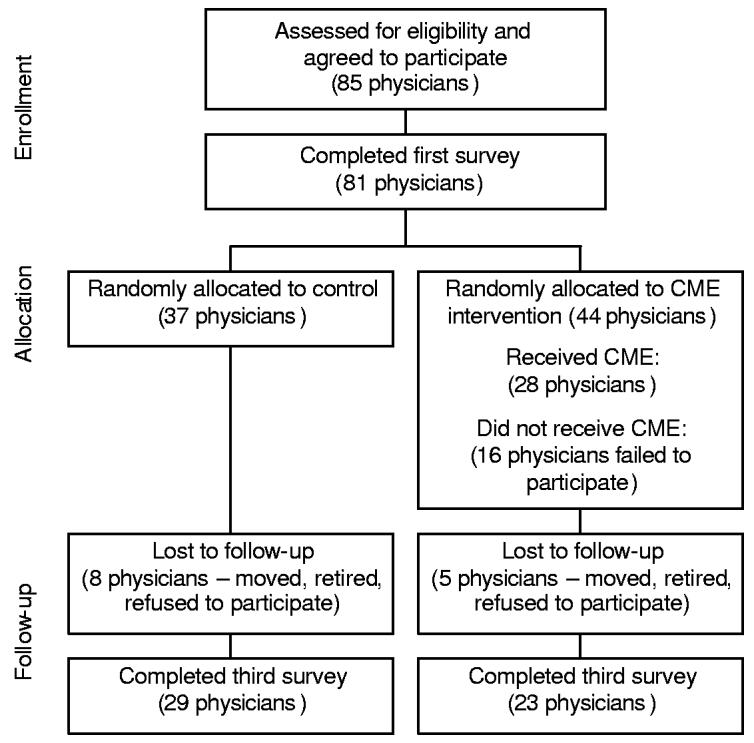

Physicians were randomly assigned to the CME (study) or to the control group, stratified by city, after completing the initial KABB survey and site visit (see Figure 1). All physicians in an office were assigned to the same study or control group. Physicians assigned to complete the online CME program had to do so within 2 months of randomization to continue in the study. More than one physician per office could participate.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of progress through study

Online IPV CME Program

A panel of experts (see Acknowledgments), led by one of the authors (ZS), developed the online IPV curriculum. It was based on current national guidelines for IPV education and included information and skill-building exercises designed to improve competencies in: the identification, assessment, and documentation of abuse and neglect; responses and interventions to ensure victim safety; the recognition of life-span issues, culture, and values as factors affecting partner violence; addressing applicable legal and forensic responsibilities; and the implementation of violence prevention strategies.11,15 The curriculum recognized the need for multiple approaches to improving care for IPV patients and encouraged the adoption of a practical, systems-based strategy that has been used successfully in clinical settings.16

The curriculum was converted into an asynchronous online IPV E-teaching program that adhered to current design principles for effective online education programs, including the use of multiple media, interactivity, and clinical cases.17 Within a set of general requirements, the user was allowed to explore important IPV issues and construct her/his own learning experience via audio, video, and text-based materials.18 Physicians could gain access to as many as 170 hyperlinks to National Library of Medicine journal abstracts; 66 multimedia mini-tutorials on key aspects of IPV; five brief video presentations by experts; 12 downloadable practice tools (e.g., patient handouts, pocket guides, and consent forms); and a complete database of state reporting requirements for partner, child, and elder abuse.

The core teaching element of the CME program was 17 interactive cases that simulated typical IPV presentations in four clinical specialties: family/internal medicine, obstetrics/gynecology, pediatrics, and mental health. There was also a single case dealing with a skin lesion and a patient's “readiness to change” her IPV relationship. All cases were designed around the elements of successful high-fidelity simulations as discussed by Issenberg et al.19 Cases were linear; there were no alternative outcomes based on user decisions. All decisions were multiple choice; there was no use of free text entry in the program. Each set of cases in a specialty area was designed to, cumulatively, cover all major IPV teaching objectives. To receive the 4 hours of CME credit required by the study, physicians had to complete all cases in their clinical specialty (3–4) and the “readiness to change” case. After completing their required cases, they could study other cases for additional credit. There was no final exam for the program.

The online CME program was developed using standard programming tools and hosted on a server in Tucson. The program was tested for compatibility with common browsers, including those offered by Microsoft® and America Online®. There were viewing options for very slow speed (<56 kilobits per second, KBS); slow speed (< 150 KBS); intermediate speed (<500 KBS); and high-speed (≥ 500 KBS) connections. The primary difference was that video files were smaller for lower bandwidth users and these users were given an audio-only or text-only option for multimedia files. The case studies did not use video; therefore, the core teaching elements were similar for low-bandwidth and higher-bandwidth users.

Educational Outcome Measures

Physician IPV KABB was measured via a self-administered, paper-based survey tool, PREMIS, described in a companion article.20 PREMIS is a comprehensive and reliable measure of physician preparedness to manage IPV in four broad areas: (1) IPV background; (2) actual knowledge; (3) opinions; and (4) practice issues (self-reported management behaviors). The 10 PREMIS scales used for this study were: (1) perceived preparation to manage IPV and (2) perceived knowledge of important IPV issues (both from the background section); (3) actual knowledge of IPV; the six reliable-opinions scales: (4) preparation, (5) legal requirements, (6) workplace issues, (7) self efficacy, (8) alcohol/drugs, and (9) victim understanding; plus (10) the practice issues scale. Information on physician prior training in IPV and other descriptive data were also collected. These data were used to compare study and control groups.

Analytic Techniques

Descriptive statistics were used to describe physician profiles. Multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) and chi square analyses were employed to test for baseline differences in demographic and background items. MANOVA was used to compare changes in the 10 PREMIS outcome scales simultaneously between the study and control groups over time (pre- to post-intervention). This technique avoided the potential for error incurred with multiple independent tests. Power calculations were conducted for a 2-group repeated measures design with three time points and an unbalanced design with 52 cases (29, 23). Considering means ranging from 3.5 to 4.5 in the intervention group, and remaining consistent at 3.5 in the comparison group, standard deviations of 1 in both groups, and correlations of 0.5 between levels of the repeated measures, the power to detect moderate effects of 0.20 was 0.88.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics and Flow Through the Study

Baseline PREMIS (KABB) data were collected in September and October 2003. Randomization occurred in October 2003. Initial post-test data were collected from March through May 2004. The second set of post-test data was collected between September and November 2004. Data were analyzed in 2005. As depicted in Figure 1, 85 physicians initially agreed to participate in the study; however, only 81 physicians completed the first PREMIS surveys. Forty-four of these physicians were randomly assigned to take the online CME. When the study concluded approximately 12 months later, 61% of the physicians had been retained through all three phases of the study, leaving 52 participating physicians (29 control and 23 study) as study participants.

There were no significant differences between study and control groups in any of the measured demographic variables. The two groups were of similar average age (47 years); gender (52%-56% male); average years in practice (17–18 years); and prior IPV training (68%–70% no training). The groups were also similar in specialty mix, patient load, and average practice size.

Use of the Online CME Program

Most of the study physicians (18/23, 78%) accessed the online CME program via moderate-speed (>150 KBS) or faster Internet connection. The average number of CME credits earned was 5.7, although the majority (15/23, 65%) of participants completed only the minimum amount of CME (4 credits). Two physicians completed all cases, earning 16 CME credits. Since physicians could be logged on to the program, but not using it, it was not possible to measure the time that physicians actively spent participating in the CME program.

Changes in Educational Outcomes Over Study Period

The MANOVA results showed a significant time by group interaction for the overall physician PREMIS scores (Wilks' Lambda = 0.274; p=0.001), indicating a change over 12 months for the study group that was significantly greater than for the control group. There were significant positive changes for the two Background PREMIS scales (Perceived Preparation, p =0.000 and Perceived Knowledge, p=0.000); five of the six Opinion scales (Preparation, p =0.000; Legal Requirements, p =0.011; Workplace Issues, p=0.002; Self-Efficacy, p=0.013; and Victim Understanding, p =0.044); and the Practice Issues scale (p =0.000). Actual Knowledge also improved, but the change was only significant at p= 0.10 (p =0.06). The only scale that clearly showed no improvement was the Opinions scale related to Alcohol/Drugs and IPV (p=0.445).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that an asynchronous, interactive, online CME program developed by a cadre of national experts (see Acknowledgments), in accordance with current online education best practices, can be successful in changing a number of physicians' IPV knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported behaviors and practices, and that these changes can persist over at least 12 months. Importantly, these positive outcomes occurred in the absence of other systems changes that are typically associated with IPV educational interventions, which could also contribute to the effectiveness of such interventions. It is quite likely that the changes seen here can be attributed to the educational program alone.

One study weakness was the loss of participants as the study progressed. Despite strong endorsements by local physician leaders, small financial incentives, and the halo of NIH-supported educational research, only 60% of the physicians who initially agreed to participate actually completed the entire study. Within this group, only 54% who agreed to do so actually completed the CME program. There were no baseline differences between the study and control groups, or between dropouts and those who completed the study, but one cannot be sure that this loss of participants did not introduce an unmeasured bias. This limitation should be considered in light of well-recognized problems in implementing rigorous experimental designs in educational settings.21 The pre-test–post-test design, the well-matched community-based controls, and the duration of follow-up lend credence to a conclusion that the online IPV program, which is available for distribution and for scrutiny by physicians, healthcare organizations, and other educators, was effective in improving important educational outcomes in those physicians who were motivated to complete the CME program. This study overcomes many of the limitations Regehr22 describes of studies of medical education.

Another weakness was that the change in physician self-reported IPV management practices (behaviors) following the CME program was not independently verified by chart audits, referral rates, or other patient-related measures. Such data are useful and valuable, but increasingly difficult to obtain in community settings because of the recognized burden of compliance with federal privacy requirements.23,24 In general, we have found a good correlation between physician self-reported IPV behaviors and overall office practices.20 Others also report good correlation between reported and measured physician behavior in other settings.25 Moreover, the presence of a control group that did not report a change in practices lends credence to a belief that the CME program positively affected actual IPV management.

While effective and easily distributed educational programs such as this may contribute to improving the physician management of IPV, they are probably not sufficient to improving IPV health outcomes on their own.26,27 As noted by others, improvement in IPV health outcomes almost certainly includes changes in law enforcement policies, improved advocacy services, and multi-disciplinary treatment approaches,28,29 in addition to practitioner training and education.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the expert consultant team who helped develop the online curriculum: Elaine Alpert MD, MPH (Boston University); Denise M. Dowd, MD, MPH (Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City MO); Christine Fiore, PhD (University of Montana); Jennifer Gunter, MD (University of Colorado); Randa M. Kutob, MD (University of Arizona); Penny Randall, MD; Patricia Salber, MD; and Ellen Taliaferro, MD. The authors also thank Stephen Buck, PhD, for his assistance with data preparation and analysis.

Footnotes

Funding/Support

The development of the online CME program and the research study were supported by a Small Business Innovation and Research (SBIR) Grant, R44-MH62233 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

IRB Review

This project was determined to be exempt from the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, pursuant to 45 CFR 46.101(b), by NIH Scientific Review Group ZRG1 SSS-D (10) on November 2, 2002.

No financial conflict of interest was reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kramer A, Lorenzon D, Mueller G. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson M, Elliott BA. Domestic violence among family practice patients in midsized and rural communities. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–746. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Department of Justice . Surgeon General's Workshop on Violence and Public Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Washington, DC: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt EN., Jr. Curricular principles for health professions education about family violence. Acad Med. 1997;72(SupplJan):S51–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Short LM, Johnson D, Osattin A. Recommended components of healthcare provider training programs on intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohn F, Salmon ME, Stobo JD, editors. The Education and Training of Health Professionals on Family Violence. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC, et al. Identification and management of domestic violence – A randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short LM, Hadley SM, Bates B. Assessing the success of the WomanKind program: an integrated model of 24-hour health care response to domestic violence. Women Health. 2002;35:101–119. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis DA, O'Brien MAT, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education - Do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior and health outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on the Training Needs of Health Professionals to Respond to Family Violence . Confronting Chronic Neglect: The Education and Training of Health Professionals on Family Violence. Institute of Medicine National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris JM, Novalis-Marine C, Harris RB. Women physicians are early adopters of online CME. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:221–228. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fordis M, King JE, Ballantyne CM, et al. Comparison of the instructional efficacy of Internet CME with live interactive CME workshops – A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris JM, Kutob RM, Surprenant ZJ, Maiuro RD, Delate TA. Can Internet-based education improve physician confidence in dealing with domestic violence? Fam Med. 2002;34:287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpert E, Tonkin A, Seeherman A, et al. Family violence curricula in U.S. medical schools. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCaw B, Berman WH, Syme SL, Hunkeler EF. Beyond screening for domestic violence: a systems model approach in a managed care setting. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:170–176. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casebeer LL, Strasser SM, Spettell CM, et al. Designing tailored Web-based instruction to improve practicing physicians' preventive practices. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5.3.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alessi SM, Trollip SR. Multimedia for Learning: Methods and Development - Third Edition. Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 2001. Learning principles and approaches; pp. 16–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Gordon DL, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27:10–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590500046924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Short LM, Alpert E, Harris JM, Surprenant ZJ. PREMIS: A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage IPV. Am J Prev Med. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.009. xxxx;yy:zz-zz (companion article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carney PA, Nierenberg DW, Pipas CF, Brooks WB, Stukel TA, Keller AM. Educational epidemiology: Applying population-based design and analytic approaches to study medical education. JAMA. 2004;292:1044–1050. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regehr G. Trends in medical education research. Acad Med. 2004;79:939–947. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulynych J, Korn D. The new HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) Medical Privacy Rule: help or hindrance for clinical research? Circulation. 2003;108:912–914. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080642.35380.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong D, Kline-Rogers E, Jani SM, et al. Potential impact of the HIPAA privacy rule on data collection in a registry of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1125–1129. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. Determinants of physician use of an ambulatory prescription expert system. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74:711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell JC, Coben JH, McLoughlin E, et al. An evaluation of a system–change training model to improve emergency department response to battered women. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, Peterson R, Saltzman LE. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers: Barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:230–237. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalk R, King P. Assessing family violence interventions. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women. JAMA. 2003;289:589–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]