Abstract

Objectives

1) To develop and teach a brief intervention (BI) for “hazardous and harmful” (HH) drinkers in the emergency department (ED); 2) to determine whether emergency practitioners (EPs) (faculty, residents, and physician associates) can demonstrate proficiency in the intervention; and 3) to determine whether it is feasible for EPs to perform the BI during routine clinical care.

Methods

The Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI) was developed for a population of HH drinkers. EPs working in an urban, teaching hospital were trained during two-hour skills-based sessions. They were then tested for adherence to and competence with the BNI protocol using standardized patient scenarios and a checklist of critical components of the BNI. Finally, the EPs performed the BNI as part of routine ED clinical care in the context of a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of BI on patient outcomes.

Results

The BNI was developed, modified, and finalized in a manual, based on pilot testing. Eleven training sessions with 58 EPs were conducted from March 2002 to August 2003. Ninety-one percent (53/58) of the trained EPs passed the proficiency examination; 96% passed after remediation. Two EPs left prior to remediation. Subsequently, 247 BNIs were performed by 47 EPs. The mean (±standard deviation) number of BNIs per EP was 5.28 (±4.91; range 0–28). The mean duration of the BNI was 7.75 minutes (±3.18; range 4–24).

Conclusions

A BNI for HH drinkers can be successfully developed for EPs. EPs can demonstrate proficiency in performing the BNI in routine ED clinical practice.

Keywords: alcohol problems, brief interventions, motivational enhancement

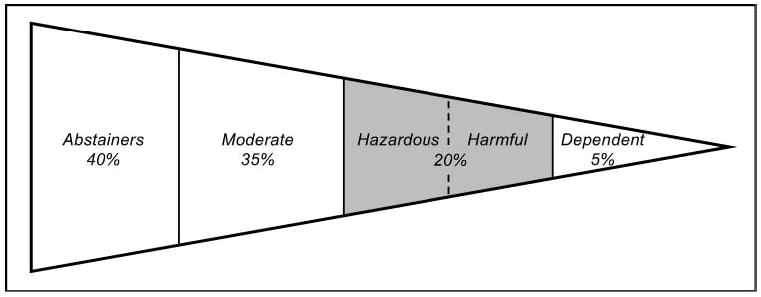

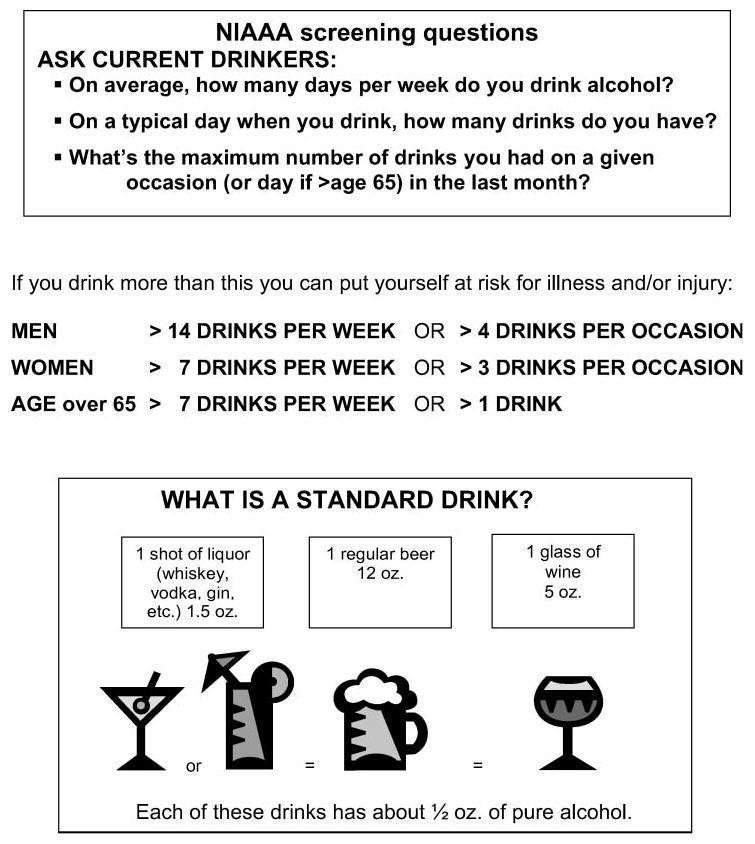

Alcohol-related problems are prevalent in the emergency department (ED) population and cover a wide spectrum of misuse, ranging from at-risk drinking patterns to dependence (Figure 1).1 The cost of these problems to society is more than $185 billion annually,2 with far-reaching implications for the individual, family, workplace, community, and entire health care system. Hazardous, also known as “at-risk,” drinking levels are defined as those exceeding the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines for low-risk drinking identified by the three recommended quantity and frequency screening questions outlined in Figure 2.3 By definition, these drinkers are at risk for future medical, social, or legal consequences. Harmful drinkers are those patients who present with a negative consequence related to alcohol. It is estimated that approximately 20% of the population in the United States over the age of 12 years are hazardous and harmful (HH) drinkers,4 and that they represent approximately 17% of patients seen in primary care practices5 and are a significant proportion of ED patients.6–8

Figure 1.

The Spectrum of alcohol use.

Figure 2.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) screening questions and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Adapted from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems: A Health Practitioner’s Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2004 (NIH publication no. 04-3769).

There is compelling evidence in the literature that brief interventions (BIs) for alcohol-related problems are effective in a variety of settings, including the ED,9–11 primary care,12 and inpatient trauma13 settings. There is some evidence that moderate drinkers may receive the greatest benefit from BI.13

Despite the magnitude of the problem and the compelling evidence that BI is effective, few emergency practitioners screen for alcohol-related problems, much less intervene once misuse is identified.14,15 The chaotic ED environment, lack of sufficient staff and resources, and characteristics of practitioners such as low levels of confidence in their skills and negative attitudes toward patients with drinking problems are often cited as significant obstacles to such screening and intervention.14,16 The interventions used in previous studies were lengthy, lasting 30–60 minutes, and were not performed by existing ED staff, but rather by non-ED staff, including a doctoral-level psychologist13 and social workers or graduate students.9,10 The need for an effective intervention aimed at reducing the deleterious effects of HH drinking, that is feasible for administration by ED staff, is critical. However, in order for this to be translated into practice, the intervention needs to be acceptable to ED staff and feasible for emergency practitioners (EPs) (faculty, residents, and physician associates) to provide in a real-world setting.

The purpose of the current study was to develop and implement a BI for HH drinkers, along with an educational strategy for teaching EPs, that can be delivered in a relatively short amount of time, as part of routine practice. In addition, we evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of both the intervention and the teaching strategy. These efforts were part of a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of a BI versus a minimal-control treatment for reducing alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational study examined the feasibility and acceptability of teaching and implementing an EP-performed brief intervention for ED patients with HH drinking. The EPs involved staffed the ED of an urban, teaching hospital, Level 1 trauma center with an annual census of approximately 64,000 adult patients. The institution’s human investigation committee approved the study protocol.

Selection of Practitioners

All emergency medicine (EM) faculty members, EM senior residents (third-and fourth-year), and physician associates (PAs) working in the ED during the study period from March 2002 to December 2003 were eligible and were invited to participate in the project.

Development of the Brief Negotiation Interview

We developed a brief intervention, entitled the Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI), adapted from an earlier intervention previously described.11,17 Brief interventions are short counseling sessions, ranging from 5 to 60 minutes, that incorporate feedback, advice, and motivational enhancement techniques to assist the patient in reducing his or her alcohol consumption to low-risk guidelines, thereby reducing the risk of illness/injury. In order to be feasible for the ED setting, we developed a BI that can be conducted in less than 10 minutes. Our BNI is a manual-guided patient-centered approach based, in part, on the patient’s motivational readiness to change. Once developed, the BNI was pilot-tested in ED patients with HH drinking and subsequent modifications were made prior to creation of the final manual and physical prompts.

Components of the BNI

The BNI has four major components, which are best described in the following steps: 1) Raise the Subject of alcohol consumption; 2) Provide Feedback on the patient’s drinking levels and effects; 3) Enhance Motivation to reduce drinking; and 4) Negotiate and Advise a plan of action. Each step has specific objectives that can, in most cases, be successfully achieved if the EP adheres to the explicitly scripted procedures shown in Table 1, each of which is discussed in greater detail below.

TABLE 1.

Steps in the Brief Negotiation Interview

| 1. Raise subject | • Hello, I am _____. Would you mind taking a few minutes to talk with me about your alcohol use? |

| <<PAUSE>> | |

| 2. Provide feedback | |

| • Review screen | • From what I understand you are drinking [insert screening data] … We know that drinking above certain levels can cause problems, such as [insert facts] … I am concerned about your drinking. |

| • Make connection | • What connection (if any) do you see between your drinking and this ED visit? |

| If patient sees connection: reiterate what patient has said | |

| If patient does not see connection: make one using facts | |

| • Show NIAAA* guidelines and norms | • These are what we consider the upper limits of low-risk drinking for your age and sex. By low-risk we mean that you would be less likely to experience illness or injury if you stayed within these guidelines. |

| 3. Enhance motivation | |

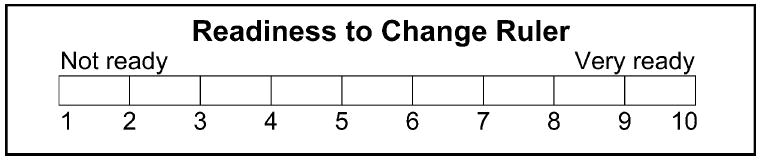

| • Readiness to change | • [Show readiness ruler] On a scale from 1 to 10, how ready are you to change any aspect of your drinking? |

| • Develop discrepancy | • If patient says: |

| ≥2 ask Why did you choose that number and not a lower one? | |

| ≤1 or unwilling, ask What would make this a problem for you? … How important would it be for you to prevent that from happening? … Have you ever done anything you wish you hadn’t while drinking? Discuss pros and cons. | |

| 4. Negotiate and advise | |

| • Negotiate goal | • Reiterate what patient says in step 3 and say, What’s the next step? |

| • Give advice | • If you can stay within these limits you will be less likely to experience [further] illness or injury related to alcohol use. |

| • Summarize | • This is what I’ve heard you say. Here is a drinking agreement I would like you to fill out, reinforcing your new drinking goals. This is really an agreement between you and yourself. |

| • Provide handouts | • Provide: |

| • Drinking agreement [patient keeps 1 copy] | |

| Project ED Health Information Sheet | |

| • Suggest primary care follow-up | • Suggest primary care follow-up to discuss drinking level/pattern |

| • Thank patient | • Thank patient for his or her time |

NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Raise the Subject

In this first step of the BNI, the EP attempts to bring up the issue of alcohol use and its possible consequences in a nonconfrontational, non-stigmatizing, and constructive manner. This is done by having the EP introduce himself or herself and ask permission to discuss the patient’s drinking.

Provide Feedback

The EP reviews the patient’s drinking amounts and patterns, making a connection between drinking and the ED visit or other health consequences/concerns whenever possible. The ED visit offers a potential “teachable moment” due to the possible negative consequences associated with the event.18 Low-risk amounts of alcohol consumption appropriate for the patient’s age and gender are reviewed. The EP explains that staying below these “upper limits” (not “norms” or “safe drinking”) is the best way to avoid future problems related to alcohol consumption, especially injury and illness. If necessary, the EP compares the patient’s current level of drinking with national data. This is an opportunity for the practitioner to state the medical facts and associations between drinking and current, past, or potential injuries or illnesses. If the patient does not make the connection, the practitioner can provide this information. For example, even if a motor vehicle crash (MVC) is not technically the patient’s legal fault, one can state that reaction times are slowed after even one drink, and certain cues on which one relies in order to drive defensively may be lost because of impaired judgment due to effects of the alcohol. Sometimes patients may be unwilling to associate their ED visits with alcohol use. If this occurs, the EP should not force the issue by pressuring the patient to acknowledge a connection, but should be sure that the patient hears that, in the EP’s medical opinion, a connection does exist (i.e., agree to disagree). It may be helpful to try and find some other negative, nonmedical consequence of drinking (e.g., drinking-related tardiness at or absences from work) that the patient can agree is related to alcohol and bothersome enough to consider drinking less.

Enhance Motivation

The primary objective of this step is to elicit and reinforce the patient’s motivational statements regarding change. These motivational statements may come in any number of forms, but usually pertain to one of the following: 1) a desire or need to change, 2) readiness to start changing presently, or 3) a belief that one has the ability to change. The first step in this endeavor is to assess motivation, which, in the BNI, is done simply by asking the following question—“On a scale from 1 to 10, how ready are you to change any aspect of your drinking?”—where 1 is “not ready,” and 10 is “very ready” (Figure 3). The EP is advised to avoid the use of the words “problem” and “abuse” in relation to alcohol. Once a number along the continuum is chosen by the patient, the EP should then ask, “why not less?” For example, if the patient chooses a 4, the EP responds positively, “that’s great, you are 40% ready for change. Tell me why you did not choose a 2 or a 3? In other words, what are some of the reasons you are ready to make a change?” This helps to generate motivational statements that can then be repeated or reflected back to the patient, thereby reinforcing his or her own incentives for change.19 Because patients are often ambivalent about change, developing discrepancies between the patient’s present drinking patterns and his or her own expressed concerns, as identified by the above ruler exercise, may tip the scales toward readiness to change. In order to strengthen or reinforce these motivational statements (e.g., a patient’s listing reasons why he or she should reduce his or her use of alcohol), EPs are trained in the technique of reflective listening. Specifically, the EP reiterates or reflects back to the patient what he or she said and, if helpful, has the patient elaborate briefly on it. This technique is based on an effective method used with a wide range of substance-using individuals to promote change.20 Most often patients choose a number between 2 and 10. Rarely, a patient may choose a 1 or be unwilling to self-identify anywhere along the ruler. There are several strategies for handling this: 1) Make sure the patient understands the question by using words to “anchor,” or give a more concrete meaning to, the numbers on the scale. For example, anchor the numbers with descriptors, such as “1” means “not ready at all” or “0% ready,” and “10” means “completely ready” or “100% ready” to change. 2) Ask “What would make this a problem for you?” (encouraging the patient to think about the future). 3) If the patient gives an appropriate response to the question in strategy 2, then ask, “How ready are you to work toward preventing this?” 4) Discuss the pros and cons of the patient’s current level of drinking. 5) Encourage the patient to think about previous times he or she has cut back on drinking. 6) Praise the patient’s willingness to discuss such a sensitive topic as well as his or her willingness to even consider change.

Figure 3.

The readiness to change ruler.

Negotiate and Advise

The primary aim of this last step of the BNI is to negotiate a realistic and constructive goal with regard to a patient’s drinking amounts and patterns. This is done by asking the patient the open-ended question, “Given what we’ve discussed, what’s the next step with regard to your drinking or what, if anything, might you consider changing about your use of alcohol?” Reinforce that for a patient with a strong family history of alcohol dependence, the goal is to stay within the low-risk guidelines. However, if the patient cannot stay within these limits, abstinence may be necessary. If the goal falls short of the recommended guidelines, the practitioner may push the boundaries a little more by saying something like, “if you could drink even less, as we discussed a few minutes ago, you could potentially have even more protection against those adverse alcohol-related consequences you are concerned about.” Tell the patient that, again in your medical opinion, the best recommendation is to cut back to low-risk drinking limits, but that any step in that direction is a good start.

At this point, the negotiation ends and the patient’s goal is then written on the drinking agreement. Prior research on responding to resistance to setting the most therapeutic goals has suggested that going beyond a neutral but clear statement about the medical appropriateness of the goal, or confronting or pressuring the patient, only leads to an increase (versus a reduction) in resistance—the patient might stop the encounter altogether. Regardless of the individual’s goal, complete and summarize very briefly the drinking agreement and provide the practitioner’s advice on following up with the primary care physician regarding the patient’s efforts to reduce his or her drinking, and provide a handout with information similar to that provided in Figure 2. Finally, thanking the patient for his or her time is essential.

Additional strategies

Sometimes additional motivational strategies are necessary to assist the patient in changing his or her drinking behavior. Some helpful hints in this regard can help the EP from falling into traps that may enhance resistance. They are outlined in Table 2. In addition, common problems encountered during the BNI and potential solutions are outlined in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Motivational Strategies for Use during the Brief Negotiation Interview

| Motivational Strategies | Patient Response | Provider Response |

|---|---|---|

| Refrain from directly countering resistance Statements | “How can I have a drinking problem when I drink less than all my buddies?” | Reply without insisting that there is a problem, but an issue worthy of further assessment and discussion |

| Focus on the less-resistant aspects of the statement | [Patient may be wondering how much drinking causes a problem] | Restate patient concern and ask about his or her level of drinking. Make the statement, “It sounds like you’re confused about how you could have an issue with your drinking if you drink less than all your friends. I’d like to tell you.” |

| Restate positive or motivational statements | “You know, now that you mention it, I feel like I have been overdoing it with my drinking lately; I guess I might have to change my drinking” | “You don’t need me to tell you you’ve been drinking a little too much lately, you’ve noticed yourself; It sounds like you’ve been thinking about changing because (insert patient reasons).” |

| Other helpful hints | Encourage patients to think about previous times they have cut back on their drinking. Praise patients for their willingness to discuss such a sensitive topic, as well as their willingness to even consider change. View the patient as an active participant in the intervention. |

TABLE 3.

Problems Sometimes Encountered during the Brief Negotiation Interview

| Problem | Overview and Solution |

|---|---|

| Refusal to engage in discussion of their drinking | Most patients will agree to discuss drinking, but if someone outright refuses to discuss it at all, tell him or her that you will respect his or her wishes and give him or her 3 pieces of information: |

| 1. His or her drinking exceeds low-risk drinking limits (or is harmful). | |

| 2. Low-risk drinking limits recommended for their age and gender. | |

| 3. You are concerned and the patient should cut down to low-risk drinking limits to avoid future harm. | |

| Refusal to self-identify along the readiness ruler | When this happens, it is usually a problem with understanding the numbers. |

| There are several ways of dealing with this: | |

| 1. Anchor the numbers with descriptors, such as “1” means not ready at all or 0% ready and “10” means completely ready or 100% ready to change. | |

| 2. Ask “What would make this a problem for you?” or “How important is it for you to change any aspect of your drinking?” | |

| 3. Discussion of pros and cons (refer to list). | |

| Unwillingness to associate visit with alcohol use | Don’t force the patient to make the connection, but be sure that he or she hears that in your medical opinion there is a connection. However, this connection may not be the thing that ultimately motivates the patient to change. Therefore, if this happens, try to find some other negative consequence of drinking that the patient can agree is related to alcohol and bothersome enough to consider drinking less. |

| Not ready to change drinking patterns to lower-risk | Tell the patient that the best recommendation is to cut back to low-risk drinking limits, but that any step in that direction is a good start. |

Implementation

Training

Two-hour training sessions were conducted for all practitioners. Training was conducted by the investigators who developed the intervention. All sessions included three faculty members, an emergency physician, a clinical psychologist, and a general internist. Prior to the training session, one pilot session was conducted and videotaped with three EPs: one faculty member, one resident, and one PA. Timing and content were reviewed to enhance the subsequent sessions. Prior to all training sessions, the participants received a written manual including all the information that would be discussed during the training program. The sessions involved: 1) a 30-minute didactic presentation, followed by 2) a 10-minute role-play demonstrating a common ED scenario using the video produced during the pilot, for consistency, 3) a 50-minute skills-based workshop, and 4) reconvening for a question-and-answer period. During the didactics portion, EPs received a broad overview of the scope of the problem of alcohol use in the ED, the spectrum of alcohol-related problems encountered, terminology regarding alcohol use and misuse, and components of the BNI technique. The actual role play is included in Table 4 (available as an online Data Supplement at: http://www.aemj.org/cgi/content/full/12/3/249/DC1) and provides a detailed example of the BNI. In the skills-based portion, EPs were divided into groups of three, each having an opportunity to assume the roles of provider, patient, and observer for three scripted ED scenarios. Each group had an instructor to oversee the practice session and offer guidance and advice. Each participant received a laminated action card listing the intervention steps for use in the clinical area.

Testing

All trained EPs were tested to ensure adherence to and competence with the BNI protocol prior to performing interventions during the randomized controlled trial. The testing occurred at a later date after the training. Residents were tested just prior to their next month’s rotation in the ED. Testing included the use of a standardized patient scenario. All sessions were audiotaped. A tape rater determined whether critical actions were completed using a BNI adherence and competence checklist. If the EP failed the testing station, he or she was given additional instruction and retested at a later date.

Data Collection

A brief, structured exit interview was performed with the EP by study research associates, after their completion of the subject intervention. The interview was designed to identify problems encountered during the intervention and allowed the EP to provide comments regarding the process.

RESULTS

EP Training and Proficiency

Between March 2002 and August 2003, 11 BNI training sessions were offered, including the one pilot session. A total of 58 EPs completed training. Two faculty members were not trained; one was completing a fellowship with only a few months remaining, and the other was on an academic sabbatical. No EP attended more than one BNI training session. Those trained were then tested; 53 (91%) passed initial testing, while five required remediation (one faculty; one resident; three PAs). Of the five needing remediation, two left the institution before the remediation could be completed (one faculty, one resident); all three PAs were successfully remediated and passed subsequent testing.

Feasibility and Acceptability

A total of 250 patients were randomized to receive BNIs during the patient enrollment period in the randomized controlled trial. Three BNIs were not performed due to critical illness: a bowel obstruction leading to surgical intervention, an evolving myocardial infarction, and an altered mental status secondary to abnormal electrolytes with an abnormal head computed tomography (CT) scan. A total of 247 BNIs were performed by 47 EPs. While 58 EPs had been trained to perform BNIs, only 47 worked clinically during subject recruitment shifts and were thus available to perform the intervention. Three interventions were completed in the inpatient unit due to: unexpected rapid admission to the floor (one), inability to find a trained EP at the time (one), and delay due to sedation of a patient received in the ED (one). The mean (±standard deviation) number of BNIs performed by each EP was 5.28 (±4.91; range 0–28). The mean duration of the BNIs was 7.75 minutes (±3.18; range 4–24).

Based on 241 EP exit interviews, 98% of 47 EPs did not encounter any problems while performing the BNI as scripted. Four (2%) reported that the BNI was interrupted due to either consultations or diagnostic testing. In all four cases, the BNI was completed subsequently. One EM resident commented that he wished all of the residents were trained, and two PAs commented that they were uncomfortable discussing drinking limits with any patient under the age of 21 years. Analysis of audiotaped ratings of EPs’ adherence to the BNI manual and competence with its four steps is ongoing.

DISCUSSION

We report the findings from the first study designed to develop, implement, and determine the feasibility of a BNI by EPs in the ED setting. Our results indicate that it is possible to design a BNI, based on the concepts of motivational interviewing, that is tailored toward HH drinkers in the ED. Our results also indicate that this version of the BNI can be taught to a wide range of EPs who subsequently demonstrate acceptable proficiency. Finally, our results demonstrate that EPs will perform the BNI in real-world settings generally within 10 minutes.

Alcohol misuse is a major modifiable public health problem. It is a risk factor in all forms of trauma and a host of medical illnesses. Training ED practitioners to incorporate the BNI into their practice is an important step toward treating a subset of patients who have a high prevalence of ED visits. Alcohol misuse problems are frequently untreated by health professionals until they develop into alcohol abuse or dependence. The ED setting is an ideal opportunity to identify and treat alcohol-related problems as patients with alcohol use disorders are more likely to present to an ED setting than a primary care setting.7

The current study demonstrates that a targeted intervention for non–alcohol-treatment-seeking HH drinkers in the ED setting can be developed, taught, and performed in a busy ED environment. Initial results from the BNI checklist of critical behaviors completed on a random sample of 30 subjects suggest that the primary components of the approach are being administered with good fidelity. While the ED is often a chaotic environment, this study demonstrated that in almost all circumstances, the practicing EP could perform the intervention. On rare circumstances this may not be feasible, such as when the patient is sedated, or the condition of the patient changes so that he or she is too ill to participate. A previous study also found that EM residents exposed to a structured skills-based educational intervention significantly improved their knowledge and practice with regard to patients presenting with alcohol-related problems.21

Successful implementation of a change in clinical practice has been associated with certain strategies, such as presence of opinion leaders, individual feedback, and system changes including innovative methods of screening and use of technology.22 Certainly in this institution there were sufficient role models to act as opinion leaders, and EPs received individual feedback regarding their performance of the intervention. Educational tools for the EP, such as quick-reference laminated action cards, and for the patient, such as show cards (as in Figure 2), handouts, and agreement forms, were provided.

LIMITATIONS

A limitation of this study is that the patients were screened by research associates and directed to the EP. Once identified, the EP performed the intervention. Instruments for identifying ED patients with HH drinking have been developed and validated.6 While the process of identifying patients with HH can add to the complexity of the BNI process, and may add an additional barrier toward the willingness of EPs to participate in the process, others have demonstrated strategies of automated screening or screening performed by ancillary staff.23–26 Finally, the additional observation inherent in a grant-funded clinical trial may have increased the motivation of EPs and helped to produce the high rate of completed BNIs.

CONCLUSIONS

A brief intervention developed for harmful and hazardous drinkers is teachable and acceptable to emergency practitioners, and feasible to perform in an urban, teaching hospital ED in the context of routine clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Patricia Owens, the Project Director, and the entire ED staff, including: the nurses, technicians, and business associates, as well as the physicians and physician associates, without whose support and efforts this study could not have been completed.

Footnotes

Presented at the American College of Emergency Physicians Research Forum, San Francisco, CA, October 2004; and the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse (AMERSA) annual meeting, Washington, DC, November 2004.

Supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA12417-01A1 (GD), National Institute on Drug Abuse grant K23 DA15144 (MVP), and the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar Award (DAF).

References

- 1.Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Report of a Study by a Committee of the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990.

- 2.Harwood HJ. Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods and Data. Report prepared by the Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD, 2000.

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems: A Health Practitioner’s Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2004 (NIH publication no. 04-3769).

- 4.Secretary of Health and Human Services. Tenth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2000 (NIH publication no. 00–1583).

- 5.Manwell LB, Fleming MF, Johnson K, Barry KL. Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use in a primary care sample: 90-day prevalence and associated factors. J Addict Dis. 1998;17:67–81. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherpitel CJ. Screening for alcohol problems in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:158–66. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherpitel CJ. Alcohol consumption among emergency room patients: comparison of county/community hospitals and an HMO. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54:432–40. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteman PJ, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR. Alcoholism in the emergency department: an epidemiologic study. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monti PM, Spirit A, Myers M, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:989–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longabaugh RH, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, et al. Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:806–16. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Levenon S. Project ASSERT: an ED-based intervention to increase access to primary care, preventive services, and the substance abuse treatment system. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;30:181–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers: a randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277:1039–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentilello LM, Rivara FP, Donovan DM, et al. Alcohol interventions in a trauma center as a means of reducing the risk of injury recurrence. Ann Surg. 1999;230:473–84. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenstein SR, Weissberg M, Terry D. Alcohol intoxication, injuries, and dangerous behaviors and the revolving emergency department door. J Trauma. 1990;30:1252–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockett IR, Putnam S, Jia H, Smith G. Assessing substance abuse treatment need: a statewide hospital emergency department study. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:802–13. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham DM, Maio RF, Blow FC, Hill EM. Emergency physician attitudes concerning intervention for alcohol abuse/dependence delivered in the emergency department: a brief report. J Addict Dis. 2000;19:45–53. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Onofrio G, Bernstein E, Rollnick S. Motivating patients for change: a brief strategy for negotiation. In: Bernstein E, Bernstein J. Emergency Medicine and the Health of the Public. Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 1996, pp 51–62.

- 18.Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Nirenberg TD, Clifford PR, Becker B, Woolard RH. Injury as a motivator to reduce drinking. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:817–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide for Practitioners. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Publishers, 1999.

- 20.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior (2nd ed). New York: Guilford Press, 2002.

- 21.D’Onofrio G, Nadel ER, Degutis LC, et al. Improving emergency medicine residents’ approach to patients with alcohol problems: a controlled educational trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:50–62. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.123693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grol R. Improving the quality of medical care: building bridges among professional pride, payer profit, and patient satisfaction. JAMA. 2001;286:2578–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfe SA, Dawson NV, Cebul RD. An automated screening strategy to identify patients with alcohol problems in a primary care setting [comment] Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:895–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barry KL, Fleming MF. Computerized administration of alcoholism screening tests in a primary care setting. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1990;3(2):93–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregor MA, Shope JT, Blow FC, Maio RF, Weber JE, Nypaver MM. Feasibility of using an interactive laptop program in the emergency department to prevent alcohol misuse among adolescents. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:276–84. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, Stocking CB, et al. Better health while you wait: a controlled trial of a computer-based intervention for screening and health promotion in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:284–291. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.110818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.