Abstract

The magnitude of mental health problems in children and adolescents has not been recognized sufficiently by many governments and decision-makers. This paper reviews the epidemiology of these problems as a basis for planning of services; the situation of mental health services for children and adolescents in the various regions of the world; the principles and strategies of intervention for mental health disorders in children and adolescents; and the role of international organizations and advocacy groups. It is concluded that old myths, treatments and policies are no longer to be tolerated and that there is now the opportunity to develop and implement evidence-based interventions, modern training programs and effective policies.

Keywords: Children, adolescents, mental health care, systems of care, global interventions

Children and adolescents have to be respected as human beings with clearly defined rights. These rights and the standards that all governments should fulfil in implementing them are fully articulated in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child. This Convention is universally applicable to children living in all cultures and societies, and has particular relevance to those living in conditions of adversity. Two additional documents have to be mentioned in connection with the convention: the Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflicts, and the Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography. All these documents provide comprehensive guidance on the human rights needs of children, adolescents and their families.

In article 3, paragraph 3, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child states: "States parties ensure that the institutions, services, and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision".

Children with mental health problems are entitled to profit from the guarantees of the Convention as stated in that paragraph. However, this is not the case in many parts of the world. The magnitude of mental health problems has not yet been recognized sufficiently by many governments and decisionmakers. They include not only welldefined mental disorders, but also the mental health problems of children exploited for labor and sex, orphaned by AIDS, or forced to migrate for economic and political reasons (1). These problems are increasing and are now quantifiable. It is estimated that in 26 African countries the number of children orphaned for any reason will more than double by 2010 and 68% of these will be as a result of AIDS. 14 million children in 23 developing countries will lose one or both parents by 2010 (2).

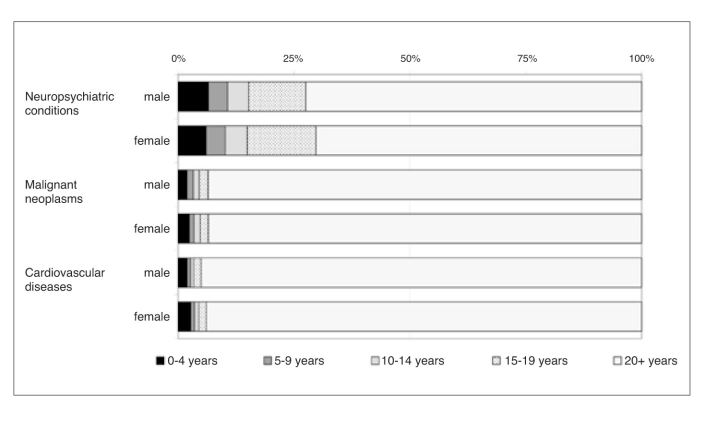

A disproportionately large percentage of the "burden of disease", as calculated by the World Health Organization (WHO), falls in the category of "neuropsychiatric conditions in children and adolescents", as shown in Figure 1. This estimate of the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) actually under-represents the burden related to these disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorders, learning disorders, mood disorders, pervasive developmental disorders and mental retardation (3). The WHO report "Caring for Children and Adolescents with Mental Disorders" (1) highlights that: a) worldwide, up to 20% of children and adolescents suffer from a disabling mental illness (4); b) worldwide, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents (5); c) major depressive disorder often has its onset in adolescence, across diverse countries, and is associated with substantial psychosocial impairment and risk of suicide (6); d) conduct disorders tend to persist into adolescence and adult life and are frequently associated with delinquency, adult crime and dissocial behavior, marital problems, unemployment and poor physical health (7).

Figure 1.

Percentage of burden of disease in disability-adjusted life years attributable to specific causes by age and sex in the year 2000 (according to the World Health Organization, 1)

The cost to society of the various mental disorders in children can now be calculated. Leibson et al (8) reported that, over a nine-year period, the median medical costs for children with ADHD were 4,306.00 USD as compared with 1,944.00 USD for children without ADHD. These data suggest that: a) mental health disorders in children represent a huge burden for the children themselves, their families, and society, and b) a rights framework is necessary for children to get appropriate, good-quality care and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AS A BASIS FOR PLANNING OF SERVICES

Epidemiological data are important for the development of public policy and programs to improve mental health in children and adolescents. Epidemiological research can provide answers to the following questions (9): a) How many children and adolescents in the community have mental health problems? b) How many children and adolescents make use of mental health services? c) What is the distribution of mental health problems and services across age, sex, and ethnic groups? d) Are there historical trends in the frequency of child and adolescent mental health problems? e) What is the developmental course of mental health problems from childhood into adulthood? f) What etiological factors can be identified to inform the design of prevention and treatment programs? g) How cost effective are child and adolescent mental health services? h) What are the outcomes for children and adolescents who received services? The answers to these questions can be used as a strong basis for planning and implementation of services.

The 6-month prevalence rates of all mental disorders in the general population (for boys and girls together) are 16.3% in 8 year olds, 17.8% in 13 year olds, 16% in 18 year olds, and 18.4% in 25 year olds. If a measure of severity is taken into account, the most severe disorders vary between 4.2% in 8 year olds and 6.3% in 25 year olds (10). Table 1 gives an overview of the prevalence of mental disorders in the general population, split up into five groups, classified according to developmental features and course of illness (11,12).

Table 1.

Prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents based on population studies in Europe and the United States (from 11,12)

| Early-onset disorders with lasting impairment | |

| Mental retardation 2% | Autism ~ 0.5‰ |

| Atypical autism 1.1‰ | Receptive language disorder 2-3% |

| Expressive language disorder 3-4% | Dyslexia 4.5% |

| Developmental disorders | |

| Disorders of motor development 1.5% | Nocturnal enuresis (in 9-year olds) 4.5% |

| Encopresis (in 7-year olds) 1.5% | Oppositional defiant disorder ~ 6.0% |

| Disorders of age-specific onset | |

| Mutism (in 7-year olds) 0.8% | Stuttering 1.0% |

| Specific phobias 3.5% | Obsessive-compulsive disorder 1.0-3.5% |

| Anorexia nervosa 0.5-0.8% | |

| Developmentally dependent interaction disorders | |

| Feeding disorder (at age 2) 3.0% | Physical abuse and neglect ~ 1.5% |

| Sibling rivalry (in 8-year olds) 14.0% | |

| Early-onset adult-type disorders | |

| Depressive episode 2.0-4.0% | Agoraphobia 0.7-2.6% |

| Panic disorder (in adolescents) 0.4-0.8% | Somatoform disorders 0.8-1.1% |

| Schizophrenia (in adolescents) 0.1-0.4% | Bipolar disorder (in adolescents) <0.4% |

| Alcohol abuse (in adolescents) ~10.0% | Alcohol dependence (in adolescents) 4.0-6.0% |

| Personality disorders (in 18-year olds) ~1.0% | |

These epidemiological data, based on studies in Europe and the United States, can be used for the planning of services in these regions of the world. They may not be applicable for the planning of services in other parts of the world, because it is important for planners to have locally relevant, culture specific data.

SYSTEMS OF CARE: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

A system of care implies that there is a range of services, from the least restrictive (community and familybased) to the most restrictive (hospitalbased). The concept of a "system" does not necessarily dictate a theoretical orientation or the therapies to be utilized. Implementation may also lack uniformity depending on the specific setting. The geographic area covered by a "system" can be as small as a local community or as large as a metropolitan city or a country. In a system, it is assumed that there is some form of facilitated transfer of the patient between the components of the continuum of care. Ensuring this facilitated flow between components of a system and ensuring good communication are difficult challenges.

Systems of care in Europe

Systems of care in Europe are very much connected with the development of child and adolescent psychiatry as a medical specialty. Child and adolescent psychiatry has its roots in the disciplines of neurology, psychiatry, pediatrics and psychology among others. Those working in the field have learned in recent decades that interdisciplinary cooperation is an absolute necessity for scientific and clinical progress. The number of child psychiatrists, as well as other child mental health workers, has dramatically increased over the last decades in nearly all European countries. The situation in the various countries, however, remains very heterogeneous with regard not only to the number of child psychiatrists, but also to the organization of departments and services, and to the research, training and continuing medical education which take place within them.

To the extent that the development of services in Europe can be seen as a model to be emulated in other parts of the world, the following conclusions can be drawn: a) the main focus of service delivery is no longer on inpatient care, but on outpatient services, day patient facilities, and complementary services based on a community level (Table 2); b) specialized services for certain disorders are provided with highly qualified personnel and pragmatic, effective and efficient treatment programs; c) programs need to be evaluated; d) the private practice of child and adolescent psychiatry varies depending on country and local circumstances; e) the coordination of the different services is too often insufficient, which represents an obstacle for the patients and affects the delivery of effective interventions.

Table 2.

Types of mental health services for children and adolescents available in most European countries

| Outpatient services | |

| • | Child and adolescent psychiatrists in private practice |

| • | Analytical child and adolescent psychotherapists in private practice |

| • | Outpatient departments at hospitals |

| • | Child psychiatric services at public health agencies |

| • | Child guidance clinics and family counselling services |

| • | Early intervention centers, social pediatric services |

| Day patient services | |

| • | Day patient clinics (two types: integrated into inpatient settings or independent) |

| • | Night clinic treatment facilities |

| Inpatient services | |

| • | Inpatient services at university hospitals |

| • | Inpatient services at psychiatric state hospitals |

| • | Inpatient services at general community hospitals or pediatric hospitals |

| Complementary services | |

| • | Rehabilitation services for special groups (e.g. children with severe head injuries, epilepsy) |

| • | Different types of residences |

| • | Residential groups for adolescents |

The Section of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry within the Union of European Medical Specialists (UEMS) has developed guidelines for training program development for child and adolescent psychiatrists. The program has been introduced in several countries of the European Union and can serve as a global model. The program identifies specific requirements and provides guidance on monitoring and quality assurance.

Systems of care in North America

After a long period of fragmented service development, the US federal government sponsored the Child and Adolescent Service System Program (CASSP), which was established in 1984 (13) and additionally supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Mental Health Service Program for Youth (MHSPY) (14). The most successful of these initiatives were based on the so-called CASSP principles (13).

According to Grimes (14), four phases in the development of services for mental disorders in children and adolescents can be distinguished: a) infrastructure (the development of better coordination and communication between service providers and the fostering of an institutionalized awareness for the necessity of a responsible infrastructure within the community); b) wrap around (the development of the means to identify needs across a set of life domains, and the shift from a focus on deficits to an emphasis on the child's and families' strengths in building interventions); c) blended funding, shared governance (the establishment of a consortium of private and public funders to support a comprehensive care program, with an adequate evaluation of efficacy and cost effectiveness); d) integrated care (the integration of mental health care with all the other care systems: medical, social and educational).

Systems of care in South America

There are no sufficient data to describe appropriately the existing systems of care in South America. The situation is different from country to country. There are excellent services in some academic centers and newly formed private clinics and hospitals. Too often nearly no services exist outside urban areas. According to WHO guidelines, at least two child psychiatrists should work full-time for each 60,000 children. South America does not meet this standard but, in some cases, this is due to an inadequate distribution of resources. The estimated number of child psychiatrists was 51 in Venezuela in 1997, and 85 in Chile in 2003 (15).

Systems of care in Asia

Hong et al (16) report on systems of care in China, Japan, Korea and the Philippines. Each of these countries has a special history concerning child mental health and related service development, but there are some common features of the status and development of child psychiatry (mental health services) in the Asian region: a) many countries still face serious problems of general health and even survival; b) child psychiatry is a newly emerging subspecialty for many countries; c) most disorders classified in DSM-IV and ICD-10 are also found in Asian countries, but there is a need for a better understanding of cultural issues; d) the breakdown of the traditional family system and the reduction in number of children is a focus of mental health concern; e) working mothers' and women's equal rights movements are becoming increasingly powerful; f) child rearing practices vary greatly and are sometimes now viewed as inappropriate; confusing and often contradictory advice is given by professionals on child rearing and behavioural management; g) mental health intervention methods are limited.

Only in recent years national and international child psychiatry organizations have been established in the Asian region. The Asian Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions (ASCAPAP) was established in 1996.

Systems of care in Australia

The vast size of Australia and its large non-urban population requires innovative service development. The main problems of mental health care for children and adolescents include (17): a) the inadequate funding for public mental health services; b) the resistance of adolescents to using mental health services; c) the irrational separation between mental health and alcohol/ substance abuse services; d) the disastrous mental health of minority populations (aboriginal families); e) a lack of understanding of the needs of children in immigrant families; f) the inadequate training of many non-psychiatric mental health staff; g) the relatively high prevalence of adolescent suicide; h) the long distance between rural patients and urban mental health services; i) the paucity of emergency, residential, partial hospital and in-home services; j) the poor coordination of services; k) the lack of funding for preventive programs; l) the high prevalence of disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety/depression, eating disorders and trauma-spectrum disorders, and m) the need to assess the quality and effectiveness of services. Important research in the field of child mental health has been carried out in Australia, and effective prevention and treatment programs have been implemented.

Systems of care in Africa

Basic needs such as nutrition, water and sanitation are the major needs in Africa, where half of the population is represented by children (18). Difficult circumstances are found in many African countries, affecting most of the basic rights of children (19), such as: a) armed conflicts and forced recruitment of children as soldiers; b) child abuse, prostitution, and trafficking; street living and homelessness child labor; HIV/AIDS pandemic; c) societies which do not provide for children's basic needs; and d) societies which allow discrimination.

Systems of care in Africa are either formal or informal (18). Informal systems include those provided by families and their support network, but also natural healers and faith-based organizations. Formal systems are provided either by the state or the emerging private sector. There are no reliable data on services in the different countries, except South Africa. A key problem is the provision of education and training programs in child and adolescent mental health not only for doctors and psychologists, but for all other health and mental health workers.

PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES OF INTERVENTION

All interventions for mental health disorders in children and adolescents should observe at least the following four principles (20):

Specificity. The most appropriate and effective treatment technique will have to be chosen for each particular disorder. In many cases, treatment will comprise a combination of those treatment techniques most likely to be specific and effective.

Age- and developmentally appropriate approach. Children at different ages and developmental stages need different types of intervention.

Variability and practicability. Ideally, one should be able to adapt a therapeutic technique to suit the setting in which the treatment is undertaken, e.g. outpatient or inpatient treatment, individual or group treatment. The treatment approach obviously needs to be practicable under the different circumstances.

Evaluation and assessment of effectiveness. The effectiveness of an intervention needs to be proven and compared with other interventions. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of empirical studies concerning many interventions in child and adolescent mental health.

Modern types of intervention for children and adolescents with mental disorders usually comprise several components. In planning and implementation of treatment, it is crucial to select the appropriate components and to integrate them into a coherent treatment plan.

Table 3 summarizes the intervention possibilities for the major mental disorders seen in children and adolescents.

Table 3.

Therapeutic interventions for priority mental disorders of children and adolescents (according to the World Health Organization, 1)

| Disorder | Dynamic | Cognitive- | Pharmaco- | Family | School | Counselling | Specialized | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| psychotherapy | behavioural | therapy | therapy | intervention | interventions | |||

| therapy | ||||||||

| Learning disorders | X | X | X | X | ||||

| ADHD | X | X* | X | |||||

| Tics | X | X | X | |||||

| Depression (and suicidal | X | X | X* | X | ||||

| behaviors) | ||||||||

| Psychoses | X | X | X | X |

ADHD - Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

*Specific treatment depends on the age of the child or adolescent

THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND CURRENT GLOBAL INITIATIVES

International organizations such as the WHO, the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), the World Federation of Mental Health, the International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions (IACAPAP), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) play an important role with regard to all aspects of child and adolescent mental health. The predominant goals and activities of these organizations are: a) to raise the awareness for child mental health; b) to facilitate the establishment of appropriate services in different parts of the world; c) to establish training programs for all mental health workers in all parts of the world; d) to fight for the rights of children and to take care that the Convention on the Rights of the Child is observed in every country. Bearing in mind these general principles, the following current global initiatives have to be mentioned.

The Atlas project

The WHO has started a series of initiatives that should enhance the capacity of countries to develop systems of care for mentally ill children and adolescents. Prime among these initiatives is the Atlas project. This project is one of the first systematic attempts to gather country-wide data on treatment resources for children and adolescents with mental disorders. The survey, using key informants, collects data on demographic health policy and legislation, mental health financing, mental health services, human resources for care, data collection capacity, care for special populations, and the use of medication. So far, 64 countries have participated.

The child and adolescent mental health Atlas follows on Atlas projects for general mental health services, neurological disorders, epilepsy, and others. The findings related to children and adolescents are striking in comparison to the data obtained for adult mental health services:

In less than 1/3 of all countries it is possible to identify an individual or governmental entity with sole responsibility for child mental health programming.

Public education about child mental health issues lags significantly behind other health related problems in all but the wealthiest countries.

The gap in meeting child mental health training needs worldwide is staggering, with between one half and two thirds of all needs going unmet in most countries of the world.

School-based consultation services for child mental health are not regularly employed in both the developing and developed world to the degree possible. This gap leads to a failure to reach children who otherwise might be helped to avoid many of the problems associated with school drop-out and other significant consequences.

Child and adolescent mental health services funding is rarely identifiable in country budgets and in low income countries services are often "paid out of pocket".

While the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is identified by most countries as a significant document, rarely are the child mental health related provisions of the Convention exercised.

The work of non-governmental organizations in the provision of care rarely is connected to ongoing country level programs and too often lacks sustainability.

The development and use of "selfhelp" or "practical help" programs, not dependent on trained professionals, in developing countries appears to be more a myth than a reality.

In 62% of the countries surveyed there is no essential drug list for child psychotropic medication. In 53% of the countries there are no specific controls in place for the prescription of medications.

Although worldwide there is a great interest in ADHD, in 47% of countries psychostimulants are either prohibited or otherwise not available for use.

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Policy Module

The Atlas project is complemented by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Policy Module, which is part of a larger mental health policy and service guidance package project. This effort comes with the recognition that there is a virtual worldwide absence of mental health policy for children and adolescents, which has hindered service development (21). The document is aimed toward ministers of health and other policy developers, and provides precise guidance on policy development to support child and adolescent mental health services. The module recognizes that, without policy at the country level, there is little likelihood of priority setting, financing, and accountability.

The WPA Presidential Global Program on Child Mental Health

The objectives of this program, supported by an unrestricted grant by Eli Lilly, are:

To increase the awareness of health decision makers, health professionals, and the general public about the magnitude and severity of problems related to mental disorders in childhood and adolescence and about possibilities for their resolution.

To promote the primary prevention of mental disorders in childhood and adolescence and foster interventions that will contribute to the healthy mental development of children and adolescents.

To offer support for the development of services for children and adolescents with mental disorders and facilitate the use of effective methods of treatment.

The program was an initiative of Ahmed Okasha, as President of the WPA, and is coordinated by an International Steering Committee, chaired by him. There are three task forces within the program: the Task Force on Awareness, the Task Force on Primary Prevention, and the Task Force on Mental Health Services, Management and Treatment. The program has led to several worldwide initiatives, e.g. field trials on school drop-out carried out in Alexandria (Egypt), Nishnij Novgorod (Russia) and Porto Alegre (Brazil). Results of the program have been presented at the World Congress of Psychiatry in Cairo.

Advocacy for services

It is a constant challenge to develop and sustain programs to support the care of children and adolescents with mental disorders.

Advocacy seeks to keep the needs of these populations on the agenda of nations and communities. Parental advocacy has been a force for the development and maintenance of programs. Professional organizations of all types have also advocated for care, but often in a manner serving the particular needs of their profession. It should be the aim of all international organizations devoted to mental health of children to facilitate broader advocacy efforts everywhere in the world.

Advocacy for child and adolescent mental health should not be the sole domain of mental health professionals or those impacted by mental disorders and their families. The health, social service, juvenile justice and education sectors also have key roles in providing advocacy for child and adolescent mental health services.

Training seminars for mental health professionals

The IACAPAP, together with the European Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (ESCAP) and the Italian Foundation CHILD, has developed a series of research seminars for child and adolescent psychiatrists and others. This movement started in Europe and is now extended to the Eastern Mediterranean region. The major aims of these seminars are to enable child psychiatrists and others to learn about and apply the most advanced diagnostic and intervention methods, to carry out high-quality research studies and to function in their region as scientific and clinical resource persons for the development and application of evidence-based diagnostic and treatment measures as well as for the establishment of appropriate services.

LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES

The main cornerstone for the improvement of child and adolescent mental health, as well as general health, is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. This convention is a powerful tool for use with governments to support the development of care for children and adolescents everywhere in the world. Other important documents and conventions of great importance are: a) the Declaration of Helsinki (1984), revised in Tokyo (1995) and in Edinburgh (2000), codifying the ethical principles of research in medicine; b) the Bioethics Convention of the European Union; c) the Belmont Report proposed by the US National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects in Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978); d) the Declaration of Madrid of the WPA (2002), containing the ethical principles of research with human beings.

The IACAPAP is an umbrella for child and adolescent mental health organizations throughout the world and has paid special attention to the promotion of the rights of children. Ethical issues have always been a major concern of the association and form an important part of its training activities.

The association has been an advocate for mentally handicapped and disabled children all over the world. In the legal sphere, its advocacy has focussed on the promulgation of declarations addressing major issues related to care, treatment and prevention, and research in child and adolescent populations impacted by mental disorders. These declarations are widely circulated as advocacy documents to ministries of health and education, key decision-makers, professionals and others, with the aim to improve the situation of mentally and behaviorally impaired children and their families.

The recent Declaration of Berlin, released on the occasion of the 16th IACAPAP World Congress in August 2004, advocates for: a) informing governments about child and adolescent mental health in the development of post-conflict programs; b) the support of national policies to foster mental health, independent of political philosophies, and to ensure continuity in programs; c) the inclusion of a provision to support child and adolescent mental health services in treaties of reconciliation, as part of essential guarantees at the cessation of hostilities; d) the initiation of sustainable mental health programs for children and adolescents.

CONCLUSION

Child and adolescent psychiatry and child and adolescent mental health services have evolved in remarkable ways in the past few decades. Old myths, old treatments and old policies are no longer to be tolerated. In this new era there is the opportunity to develop and implement evidencebased interventions, modern training programs and effective policies. Advocacy for these initiatives is the responsibility of many. The reward will be to see a healthier and happier population of children and adolescents and more productive and stable societies.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Caring for children and adolescents with mental disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster G. Supporting community efforts to assist orphans in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1907–1910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb020718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fayyad JA. Jahshan CS. Karam EG. Systems development of child mental health services in developing countries. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2001;10:745–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. World health report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. World health report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman MM. Wolk S. Goldstein RB, et al. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA. 1999;281:1707–1713. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson GR. DeBaryshe BD. Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am Psychol. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leibson CL. Katusic SK. Barbaresi WJ, et al. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2001;285:60–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhulst FC. Epidemiology as a basis for the conception and planning of services. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt MH, et al. Epidemiologie und Ätiologie psychischer Störungen im Kindesund Jugendalter. In: Blanz B, editor; Remschmidt H, editor; Schmidt MH, et al., editors. Psychische Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Stuttgart: Schattauer; (Ger). in press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remschmidt H. Schmidt MH, et al. Disorders in child and adolescent psychiatry. In: Henn F, editor; Sartorius N, editor; Helmchen H, et al., editors. Contemporary psychiatry. Berlin: Springer; 2001. pp. 60–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanz B, editor; Remschmidt H, editor; Schmidt MH, et al., editors. Psychische Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter. Stuttgart: Schattauer; (Ger). in press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroul B. Friedman R. A system of care for children and youths with severe emotional disturbance. CASSP Technical Assistance Center. Washington: George Washington University; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimes KE. Systems of care in North America. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohde LA. Celia S. Berganza C. Systems of care in South America. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong KM. Yamazaki K. Banaag CG, et al. Systems of care in Asia. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurcombe B. Systems of care in Australia. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson B. Mandlhate C. Seif El-Din A, et al. Systems of care in Africa. In: Remschmidt H, editor; Belfer M, editor; Goodyer I, editor. Facilitating pathways: care, treatment and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Nations Children's Fund. Children and development in the 1990s. New York: United Nations; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remschmidt H. Definition, classification, and principles of application. In: Remschmidt H, editor. Psychotherapy with children and adolescents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shatkin J. Belfer M. The global absence of child and adolescent mental health policy. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2004.00090.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]