Abstract

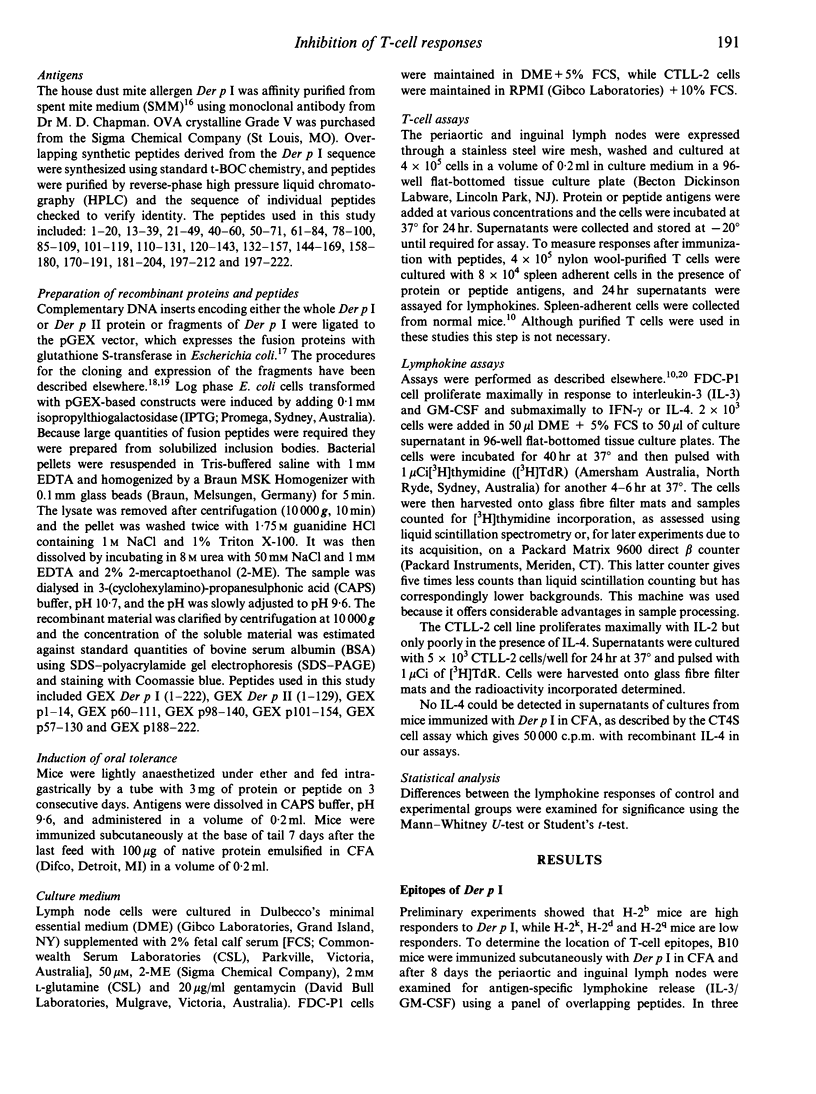

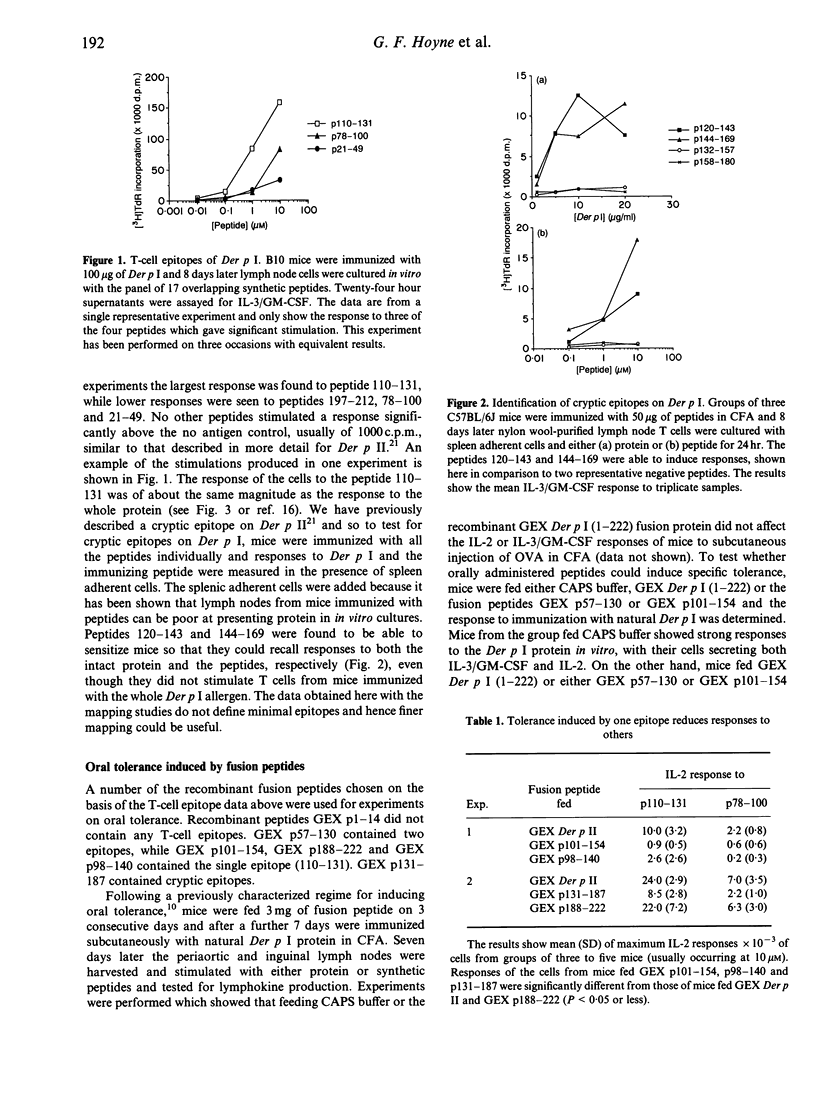

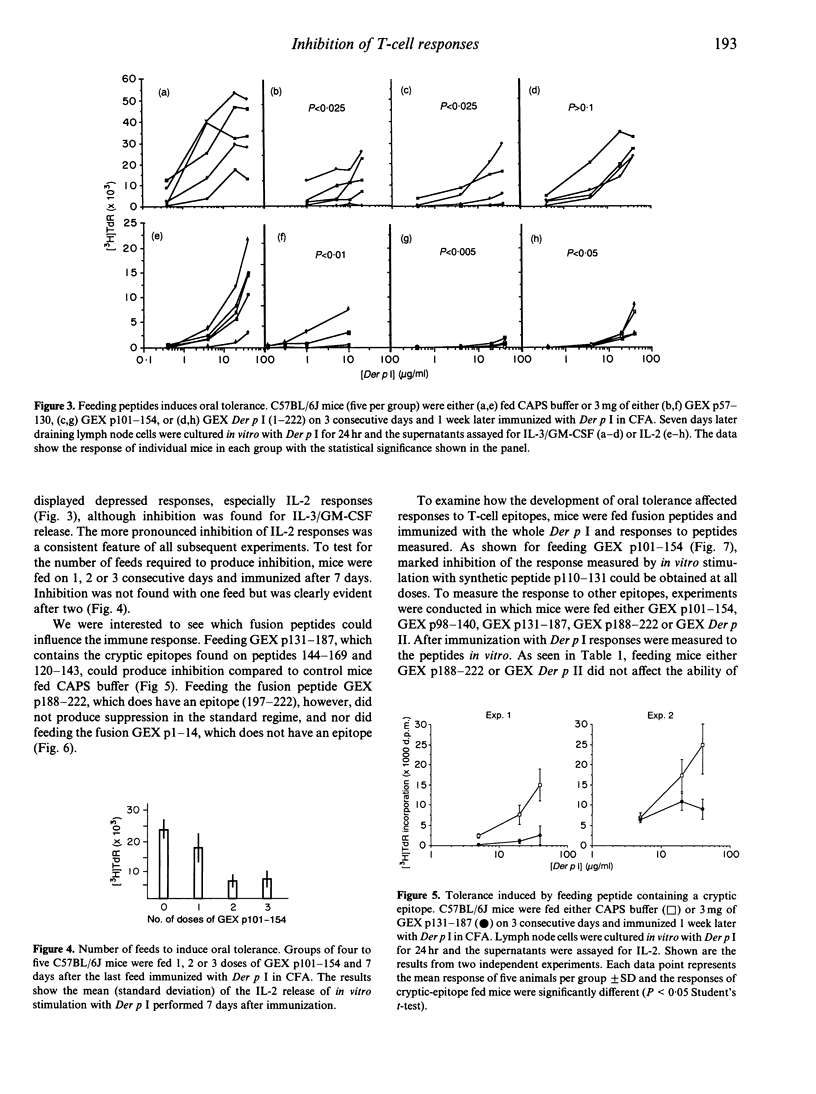

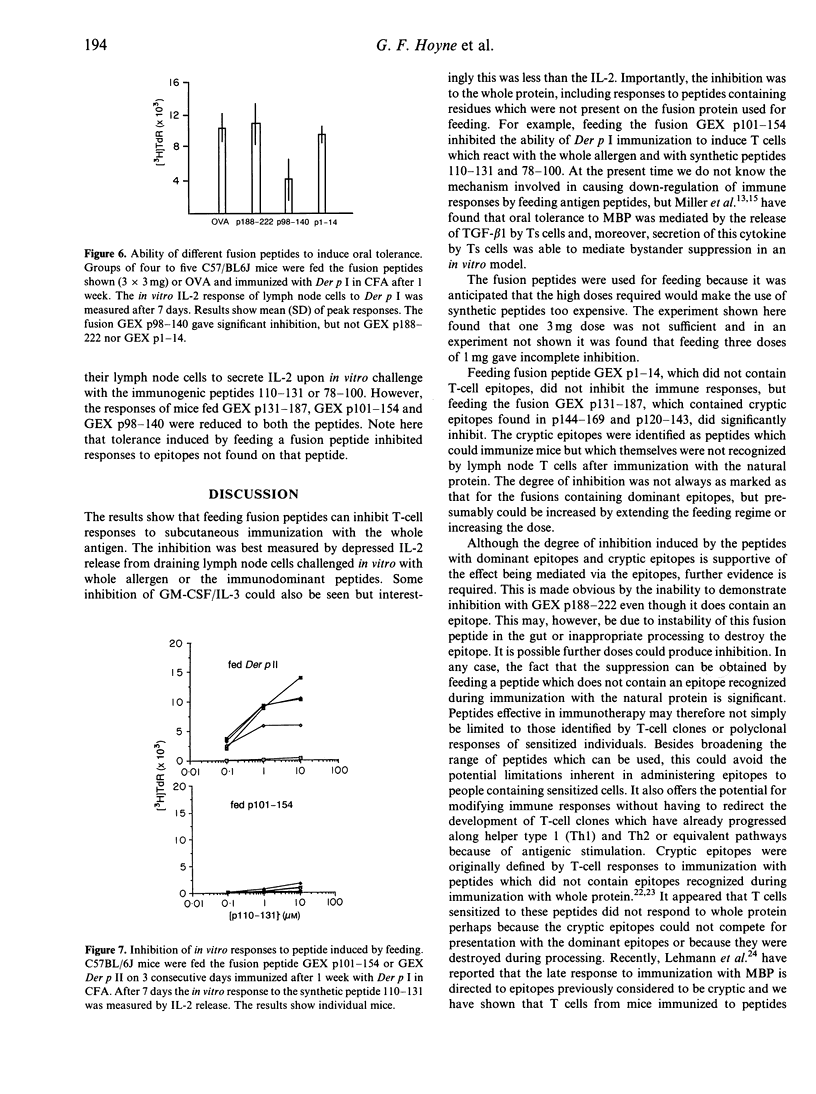

H-2b mice respond to the 222 residue allergen Der p I by producing T cells sensitized to the dominant epitopes encompassed in peptides 21-49, 78-100, 110-131 and 197-212. Immunization with the synthetic peptides 120-143 and 144-169, however, revealed cryptic epitopes which could sensitize T cells for responses to the respective peptides and, providing splenic adherent cells were added to lymph node cultures, to the whole allergen. It is shown that feeding recombinant fusion peptides can markedly inhibit the ability of the whole antigen to immunize mice, as measured by the in vitro interleukin-2 (IL-2) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)/IL-3 release on stimulation with protein or peptides, although inhibition measured by IL-2 release was more marked. The inhibition extended to epitopes other than those in the fusion peptides used for feeding. Thus feeding peptide 101-154 inhibited responses to 110-131 and 78-100. Fusion peptides 1-14 and 188-222 did not inhibit responses, although 188-222 did contain an epitope. Inhibition was also obtained when mice were fed a fusion containing the cryptic epitope 144-169. The ability of peptides containing the cryptic epitopes to inhibit responses has significant implications for peptide-based immunotherapy.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ametani A., Apple R., Bhardwaj V., Gammon G., Miller A., Sercarz E. Examining the crypticity of antigenic determinants. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):505–511. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asherson G. L., Perera M. A., Thomas W. R. Contact sensitivity and the DNA response in mice to high and low doses of oxazolone: low dose unresponsiveness following painting and feeding and its prevention by pretreatment with cyclophosphamide. Immunology. 1979 Mar;36(3):449–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asherson G. L., Zembala M., Perera M. A., Mayhew B., Thomas W. R. Production of immunity and unresponsiveness in the mouse by feeding contact sensitizing agents and the role of suppressor cells in the peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues. Cell Immunol. 1977 Sep;33(1):145–155. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(77)90142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M. G., Ferguson A. Oral tolerance to ovalbumin in mice: studies of chemically modified and 'biologically filtered' antigen. Immunology. 1986 Apr;57(4):627–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challacombe S. J., Tomasi T. B., Jr Systemic tolerance and secretory immunity after oral immunization. J Exp Med. 1980 Dec 1;152(6):1459–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.6.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua K. Y., Dilworth R. J., Thomas W. R. Expression of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus allergen, Der p II, in Escherichia coli and the binding studies with human IgE. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;91(2):124–129. doi: 10.1159/000235102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammon G., Sercarz E. E., Benichou G. The dominant self and the cryptic self: shaping the autoreactive T-cell repertoire. Immunol Today. 1991 Jun;12(6):193–195. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90052-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene W. K., Cyster J. G., Chua K. Y., O'Brien R. M., Thomas W. R. IgE and IgG binding of peptides expressed from fragments of cDNA encoding the major house dust mite allergen Der p I. J Immunol. 1991 Dec 1;147(11):3768–3773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyne G. F., Callow M. G., Kuhlman J., Thomas W. R. T-cell lymphokine response to orally administered proteins during priming and unresponsiveness. Immunology. 1993 Apr;78(4):534–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso A. Frequency analysis of lymphokine-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells activated in a graft-versus-host reaction. J Immunol. 1990 Oct 1;145(7):2167–2176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont A. G., Gordon M., Ferguson A. Oral tolerance in protein-deprived mice. II. Evidence of normal 'gut processing' of ovalbumin, but suppressor cell deficiency, in deprived mice. Immunology. 1987 Jul;61(3):339–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann P. V., Forsthuber T., Miller A., Sercarz E. E. Spreading of T-cell autoimmunity to cryptic determinants of an autoantigen. Nature. 1992 Jul 9;358(6382):155–157. doi: 10.1038/358155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Lider O., Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Weiner H. L. Suppressor T cells generated by oral tolerization to myelin basic protein suppress both in vitro and in vivo immune responses by the release of transforming growth factor beta after antigen-specific triggering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jan 1;89(1):421–425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Lider O., Weiner H. L. Antigen-driven bystander suppression after oral administration of antigens. J Exp Med. 1991 Oct 1;174(4):791–798. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat A. M., Strobel S., Drummond H. E., Ferguson A. Immunological responses to fed protein antigens in mice. I. Reversal of oral tolerance to ovalbumin by cyclophosphamide. Immunology. 1982 Jan;45(1):105–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat A. M. The role of antigen recognition and suppressor cells in mice with oral tolerance to ovalbumin. Immunology. 1985 Oct;56(2):253–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan J., Kind L. S. Suppressor T cells for IgE and IgG in Peyer's patches of mice made tolerant by the oral administration of ovalbumin. J Immunol. 1978 Mar;120(3):861–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. B., Johnson K. S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988 Jul 15;67(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel S., Mowat A. M., Drummond H. E., Pickering M. G., Ferguson A. Immunological responses to fed protein antigens in mice. II. Oral tolerance for CMI is due to activation of cyclophosphamide-sensitive cells by gut-processed antigen. Immunology. 1983 Jul;49(3):451–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. S., Staines N. A. Could specific oral tolerance be a therapy for autoimmune disease? Immunol Today. 1990 Nov;11(11):396–399. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre C. C., Gienapp I. E., Orosz C. G., Bitar D. M. Oral tolerance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. III. Evidence for clonal anergy. J Immunol. 1991 Oct 1;147(7):2155–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]