Abstract

Hypotheses were tested about how moment-by-moment variation in mothers' negative emotion predicts harsh and lax discipline. Mother–toddler dyads interacted in a task designed to elicit challenging child behavior. Mothers viewed videotapes of their interactions and continuously rated their experienced emotion. Harsh discipline was associated with mothers' greater negative emotion intensity, greater dependence of mothers' emotion on toddlers' negative affect, and lower serial predictability of mothers' emotion. Laxness was also associated with greater emotion dependence on negative toddler affect and lower serial predictability but not with negative emotion intensity. The dependence of mothers' emotion on toddlers' rule violations was not associated with discipline. Dynamic emotion variables were not redundant with emotion intensity and therefore enhance our understanding of the role of emotion in discipline.

As our theories of parenting and its determinants have become more sophisticated, the role of emotion has at times been offered as a central focus (e.g., Dix, 1991). Despite the recognized conceptual importance of emotion, the empirical database on emotion in parenting has remained scant. This article represents an attempt to further develop the theoretical and empirical basis for our understanding of parental emotion and its relation to discipline.

The perspective offered here draws on the functionalist view of emotion, currently the dominant view in emotion theory (Consedine, Strongman, & Magai, 2003). From this perspective, emotions are thought to motivate behavior, preparing individuals for action (Izard, 1991; Levenson, 1994). Negative emotions—the focus of this investigation—are elicited when circumstances are at odds with the concerns of the individual. When negative emotion is activated, the resultant action is typically directed at ending aversive stimulation or righting perceived wrongs.

To the extent that emotions motivate parental behavior, an understanding of individual differences in mothers' emotion is key to a better understanding of their behavior. Parents' emotional functioning “must be organized to a large extent around concerns and outcomes related to children's well-being and development” (Dix, 1991, p. 9). Yet mothers, particularly those of toddlers, are faced with a great deal of unpleasant child behavior that has the potential to elicit mothers' negative emotions. Normal toddlers average several episodes of misbehavior an hour, and episodes of crying, including tantrums, can occur several times a day (Roberts & Strayer, 1987). The maternal emotion states caused by aversive child behavior may, in turn, cause dysfunctional parenting behavior (e.g., overreactive discipline; E. H. Arnold & O'Leary, 1995). Therefore, the study of emotion in mothers challenged by aversive child behavior has great potential to increase our knowledge of why some parents are able to direct their behavior in service of the developmental interests of their children more so than other parents.

Most often, studies of parental emotion have focused on emotion that is expressed toward the child. Research suggests that frequent or intense displays of negative maternal affect are incompatible with effective parenting. In fact, because of their association with problematic child behavior (e.g., Denham et al., 2000), such displays of negative affect have themselves become part of the definitions of ineffective parenting. Far fewer studies have been concerned with emotion experienced by parents. This distinction is important because research suggests that emotion experienced and expressed by parents during interactions with their children tap distinct components of emotion, components that are often only modestly related (e.g., Martin, Clements, & Crnic, 2002). Further, expressed emotion has the potential to directly affect the child, whereas experienced emotion can only affect the child through its impact on parents' behavior. Because emotion expression and experience can operate somewhat independently, it is likely that the impact of emotion experience on parenting behavior is complex, with emotion experiences potentiating or inhibiting a variety of behaviors in addition to the straightforward expression of the experience.

In the literature on maternal emotion experience, investigations have focused primarily on emotion level or intensity (e.g., Dix, Ruble, Grusec, & Nixon, 1986; Smith & O'Leary, 1995). Too much emotion, too little emotion, or emotion that is incompatible with parenting tasks and child needs is thought to be problematic (Dix, 1991). Individual differences in the intensity of experienced negative emotion elicited by standard child stimuli are positively related to individual differences in harsh discipline (e.g., Smith & O'Leary, 1995) and child abuse (e.g., Frodi & Lamb, 1980). In fact, an experiment conducted by E. H. Arnold and O'Leary (1995) demonstrated that negative emotion experienced by mothers, induced by exposure to child negative affect, mediates the relation between child negative affect and overreactive discipline (E. H. Arnold & O'Leary, 1995). Also, negative emotion that is not specifically child related, such as depressed mood, is associated with poor parenting (e.g., Dumas & Wekerle, 1995).

Although research has established links between aversive child behavior and negative maternal emotion, and between negative maternal emotion and discipline, little existing research (Dowdney & Pickles, 1991; Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999) has addressed the dynamic interplay between child behavior and maternal emotion in parent–child interaction. None has examined relations between mothers' emotion dynamics and discipline. Understanding parents' emotions in relation to discipline might be useful, as discipline is critical in the development and modification of children's externalizing behavior problems (Kendziora & O'Leary, 1993). Because emotion changes from moment to moment in response to a multitude of stimuli (Ekman, 1992), incorporating dynamic emotion variables into our explanatory models of discipline might enhance them.

Given the lack of research on discipline and the dynamics of mothers' experienced emotion, this article focuses on how discipline is related to mothers' experience of negative emotion, with an emphasis on how it changes over time and in response to child behavior (i.e., emotion dynamics). Hypotheses were tested with regard to how mothers' harsh and lax discipline relates to (a) moment-to-moment variation in their experience of negative emotion and (b) the dependence of that variation on aversive toddler behavior. Although the focus of the investigation was on emotion dynamics, it also provided an opportunity to re-evaluate relations between mothers' discipline and a static measure of negative emotional intensity.

Harsh discipline comprises power assertion and irritation directed at a misbehaving child; not following through and giving in to child misbehavior characterize lax discipline. Both are associated with children's problem behavior, and thus both are major clinical targets (Kendziora & O'Leary, 1993). It was hypothesized that both harsh and lax discipline would be linked to the intensity of mothers' negative emotion, although only the emotion–harshness link has empirical support (e.g., E. H. Arnold & O'Leary, 1995; Dix et al., 1986; Smith & O'Leary, 1995). Intense negative emotion may (a) motivate mothers to give in when faced with aversive child behavior (to get the child to stop) and (b) overwhelm problem-solving skills, making lax discipline more likely (Dix, 1991). Although an earlier study did not find this link (Smith & O'Leary, 1995), the rationale outlined previously gives sufficient reason to re-evaluate this hypothesis.

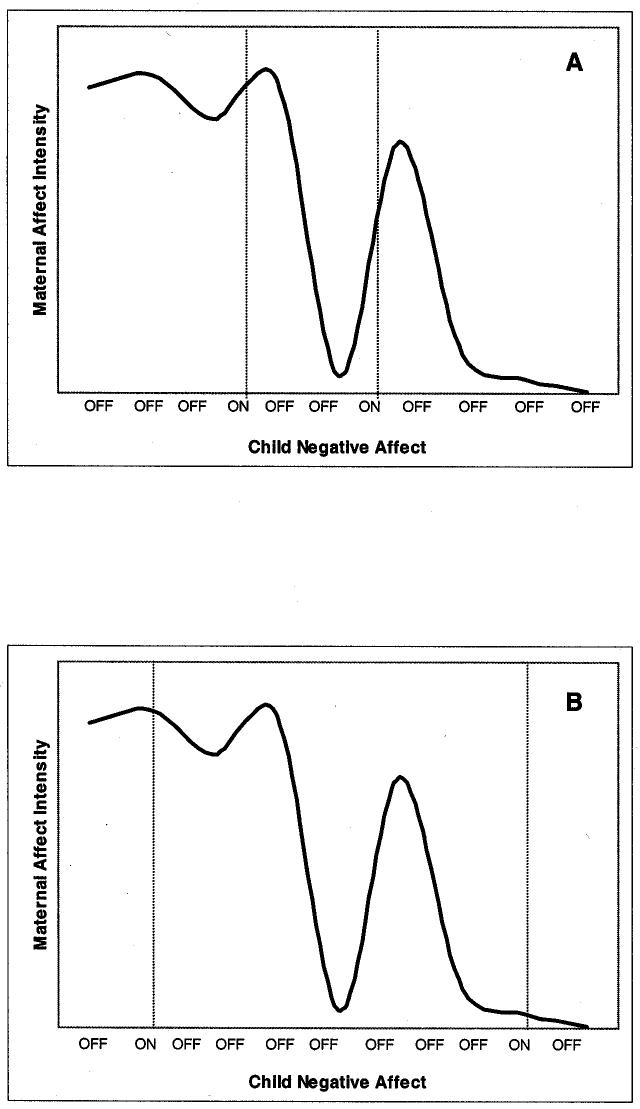

It was also hypothesized that mothers' discipline would relate to the degree to which moment-by-moment change in their experienced emotion was accounted for by moment-by-moment changes in two types of aversive child stimuli: children's rule breaking and negative affect. This dimension—the degree to which mothers' emotion dynamics are predicted by moment-by-moment changes in child behavior—is labeled emotion dependence. It was further hypothesized that the degree of this emotion dependence would predict discipline independent of mothers' average intensity of emotion. The dimension of emotion dependence is conceptually distinct from typical indexes of emotion, such as average intensity or reactivity to specific stimuli, because it is a dynamic variable that captures the degree to which maternal emotion (from very negative to very positive) rises and falls with the rise and fall of child behavior. Hypothetical patterns of high and low emotion dependence are depicted in Figure 1 (panels A and B, respectively).

Figure 1.

Illustrations of high (panel A) and low (panel B) maternal emotion dependence on negative child affect.

These hypotheses were based on a central tenet of the functionalist view of emotion—emotions serve to motivate adaptive behavior. Because negative emotion is typically associated with action directed at ending aversive stimulation or righting perceived wrongs, mothers whose feelings are extremely dependent on their children's aversive behavior might be most at risk to impulsively give in (lax) or lash out (harsh) to try to stop the unpleasant input. For these mothers, control of their negative feelings may become the central focus, with discipline responses selected for this purpose rather than for optimal socialization. Mothers whose feelings are less dependent on aversive child behavior may be less motivated to “turn off” their own negative feelings by ending children's aversive behavior. Although employing others to help regulate one's negative emotions has not been the focus of empirical study with adults, it is acknowledged in emotion-regulation theory (e.g., Gross, 1998).

It was also hypothesized that the degree of regularity in the moment-by-moment movement in mothers' emotion would be associated with discipline. This dimension—the degree to which a mother's emotion is predictable from earlier, systematic variations in her emotion—is labeled serial predictability. Serial predictability is a conceptual label for the autocorrelation of experienced emotion. Although autocorrelation is usually computed as a preliminary step in time-series analyses and controlled for in longitudinal analyses, it may have untapped substantive meaning, providing an important window on mothers' emotion-regulation resources. At the low end of this dimension, a mother's affective experience is random, indicative of erratic and potentially ineffective or maladaptive emotion regulation. At the high end, her emotion is highly patterned and predictable, indicative of more regulation. If serial predictability is viewed as the output of the process of regulating emotion, predictability from moment to moment is evidence of a regulatory process. Predictable emotion seems necessary for organized behavior. Random emotion fluctuations may undermine organized responses to unpleasant toddler behavior, making both overly harsh and permissive responses more likely.

The view of emotion regulation offered here views emotion dynamics as resulting from internal processes and environmental inputs that, taken together, account for moment-by-moment changes in emotion. To the extent that changes in emotion are predictable, there is evidence that regulation is occurring. Following Thompson's (1994) view, regulation does not need conscious control. This differs from conceptualizations that view emotion regulation as a conscious process (e.g., Dix, 1991). Instead, emotion regulation in this article refers to the product of biological, psychological, or social-regulatory processes operating on components of emotion (Thompson, 1994). Thus, predictable patterns in how mothers' emotion changes over time would evidence emotion being regulated by likely multiple processes, including basic biologic ones.

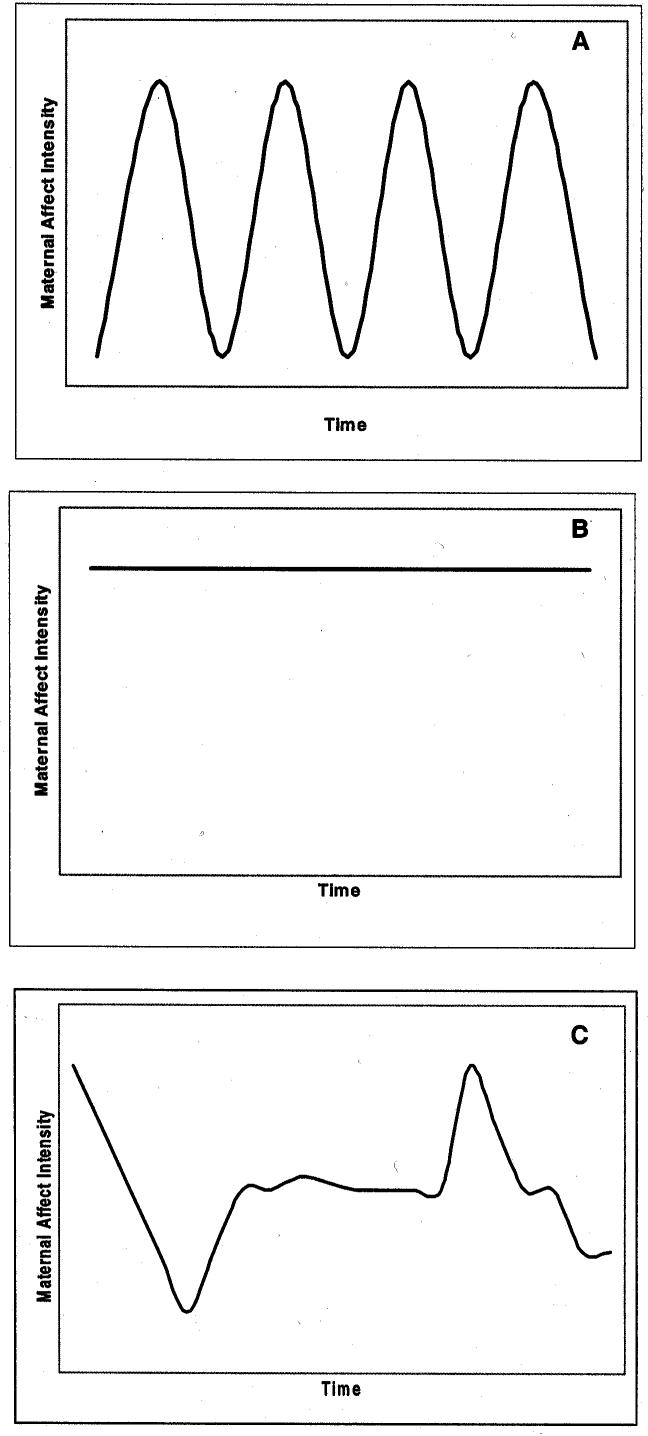

Like emotion dependence, serial predictability is conceptually independent of dimensions such as intensity and stability of emotion. Given that it represents the degree to which emotion valence and intensity at one point in time is predictable from its past, highly predictable emotion can take many different forms. For example, if a maternal emotion time series takes the shape of a sine wave (Figure 2, panel A), then each measurement point is perfectly predictable from its past. The same is true of maternal emotion that falls along a flat line over time, regardless of its level (Figure 2, panel B). Emotion with little evidence of an identifiable repeating pattern over time (Figure 2, panel C), however, is low in serial predictability.

Figure 2.

Illustrations of high (panels A and B) and low (panel C) serial predictability of maternal emotion.

In summary, four hypotheses (H) were evaluated:

H1. Emotion dependence on aversive child behavior is positively associated with harsh and lax discipline.

H2. Inverse relations exist between serial predictability of emotion and harsh and lax discipline.

H3. Negative emotion intensity is positively associated with harsh and lax discipline.

H4. Emotion dependence and serial predictability of emotion predict variance in discipline that is nonredundant with variance predicted by negative emotion intensity.

Method

Participants

To maximize the chances of observing a wide range of child behavior in the laboratory interaction, mothers were recruited via two advertisements: one targeted “mothers of toddlers,” the second targeted “mothers of hard-to-manage toddlers.” Given the well-replicated correlation between child behavior and parenting and the correlational nature of our analyses, we were concerned that recruiting a strictly “normal” sample would result in restricted range in child behavior and, therefore, discipline. The following results suggest little to no evidence of two underlying populations. The final sample's resulting distribution of externalizing scores was wide and approximately normal. Further, there were no significant differences by recruitment method for any study variable (ps > .28). Finally, only 1 of the 15 correlations examined here (6.70%) differed by recruitment method at p < .05. This proportion of significant correlation comparisons is roughly what one would expect by chance using an alpha of .05.

Forty mothers and their toddlers (20 boys) ages 17 to 36 months (M = 26.15, SD = 5.60) participated. Mothers mean age was 30.10 years old (SD = 3.93), with an average family income of $53,925 (SD = $22,454), and an average of 14.13 years of education (SD = 1.98). All mothers self-identified as Caucasian, and most (95%) were married. Externalizing factor T scores on the Child Behavior Checklist for 2- to 3-year-olds (Achenbach, 1991) ranged from 32 to 81 (M = 53.28, SD = 12.27). The income of this sample was comparable to the median family income in the county from which the sample was drawn.

Procedure

After giving written informed consent, mothers completed all questionnaires. The mother was then videotaped interacting with her child for approximately 30 min, following an established protocol for studying maternal responses to challenging toddler behavior (e.g., Lorber, O'Leary, & Kendziora, 2003; Slep & O'Leary, 1998). This interaction took place in a small room containing a chair for the mother and three low tables. Objects that are attractive to young children but are not typically considered toys (e.g., a manual typewriter; a sealed, glass jar of hard candy) were on the tables, and a mobile hung from the ceiling. The mother was instructed that her child was not to touch these objects. The interaction consisted of three tasks that presented typical but challenging situations for the mother and child. First, the mother was instructed to supervise her child cleaning up a set of toys for a maximum of 10 min. Then the mother gave the child other toys and was instructed to have the child play independently while she talked on the phone for 10 min with the experimenter. Finally, the mother was told to have the child play quietly and independently on a mat while she completed questionnaires for 10 min. The mother was told to manage her child's behavior however she usually would. The mother wore a bug-in-the-ear device to allow communication between herself and the experimenter. The experimenter cued the mother when to proceed to the next situation but offered no advice or instruction about how to manage her child.

Following the interaction, mothers watched the videotapes of their interactions and made continuous ratings of their experienced emotion using a dial apparatus similar to that used by Levenson and Gottman (1983) for the self-rating of emotion in couples. The dial was divided into three parts, with negative to the left of center, positive to the right, and neutral as the notched position in between. Ratings are expressed on a scale from −100 to +100.

Observational Measures

Discipline. Global ratings of discipline, in contrast to interval, event, or frequency approaches, were used to capture the overall quality of mothers' discipline. Such coding allowed for the joint consideration of frequency, intensity, and duration of constituent behaviors. The advantages of global coding are particularly pronounced with respect to lax parenting, which includes the absence of behavior (e.g., not following through), as behavioral omissions are difficult to capture in event-based coding approaches. Global discipline coding relates to self-reports of discipline (D. S. Arnold, O'Leary, Wolf, & Acker, 1993) and experimental manipulations of parental emotion (E. H. Arnold & O'Leary, 1995) and cognition (Slep & O'Leary, 1998).

Maternal harshness and laxness were rated for each of the three interaction tasks by trained coders blind to the hypotheses. Harshness was rated on a 7-point scale reflecting the degree and frequency of responding to child misbehavior in a hostile or power-assertive way either verbally (e.g., yelling) or nonverbally (e.g., pushing or pulling). Laxness was rated on a 7-point scale reflecting the frequency and extremity of mothers' permissive responses to child misbehavior (e.g., not following through, giving in). One set of coders coded both harshness and laxness, with 50% of the interactions coded by both coders. Reliability was excellent (Finn's rs = .99 and 1.00 for harshness and laxness, respectively). Finn's r is an alternative to the intraclass correlation for judging interobserver agreement that is less sensitive to skew (Whitehurst, 1984). The harsh and lax scores used in the analyses were the average of the ratings for each interaction task (Cronbach's alphas = .86 and .78, respectively).

Child behavior. The presence of child rule-breaking and negative affect was coded in 5-sec intervals over the entire interaction by a second set of blind coders. Rule-breaking was a summary misbehavior code, defined as violations of the rules for the interaction (e.g., touching forbidden objects, noncompliance with mother commands). Negative affect was coded if the child whined, whimpered, cried, screamed, or tantrummed. Twelve dyads (30% of the total N) were coded by both coders to determine code reliabilities. The mean Cohen's kappa was .84 for rule violations (ranging from .70 to .95), and .86 for negative affect (ranging from .72 to .94). Because the interactions had variable lengths (depending on how long the child took to clean-up the toys in the first task), the negative affect and rule violations variables reported in Table 1 were the proportion of 5-sec intervals in which each code was observed.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harshness | 40 | 1.000 | 5.330 | 2.180 | 1.110 |

| Laxness | 40 | 1.670 | 5.000 | 3.240 | 0.740 |

| Negative Maternal Emotion Intensity | 37 | −135.370 | 298.690 | −20.580 | 107.580 |

| Negative Affect | 40 | 0.000 | 0.650 | 0.310 | 0.160 |

| Rule Violations | 40 | 0.310 | 0.880 | 0.610 | 0.160 |

| Emotion Dependence on Negative Affect | 30 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| Emotion Dependence on Rule Violations | 37 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Serial Predictability of Emotion | 37 | 0.730 | 0.980 | 0.880 | 0.060 |

Maternal emotion. During video playback, mothers rated the moment-by-moment intensity of their affective experience, from extremely positive to extremely negative, using a video-mediated dial-rating procedure. The dial position was monitored and recorded by computer. For each successive 5-sec interval, the number of seconds the dial was in the negative, neutral, and positive regions, and the average position of the dial for the time it was in the negative and positive regions, were recorded. Affect scores for each interval were calculated by subtracting (a) the time the dial was in the positive region × average dial position during that time from (b) the time the dial was in the negative region × average dial position during that time. Thus, the index ranges from intensely positive emotion at the low end to intensely negative emotion at the high end. Emotion intensity scores for successive 5-sec intervals were used in the time-series analyses (described later). Overall average emotion intensity scores were the mean of all 5-sec interval scores. Higher scores indicate more intensely negative emotion.

Assessment of moment-by-moment variations in emotion experience cannot occur during the interaction without significantly disrupting it. Thus, video-mediated recall procedures have been developed and validated. This postinteraction rating procedure was developed by Gottman and Levenson (1985), who had participants rate positive to negative subjective emotion intensity, suggesting this general dimension captured the majority of variance in emotion experience and resulted in more reliable reports than assessing specific emotions. Gottman and Levenson reported a number of findings supportive of the validity of video-mediated recall-based moment-by-moment reports of experienced emotion: (a) spouses exhibit nearly the same physiological reactions during the video-recall procedure as they did during the actual couple interaction and at essentially at the same times (convergent validity), (b) experienced negative emotion was higher in a conflict discussion than in an events-of-the-day discussion and for unhappy versus happy couples (discriminant validity), (c) husbands' and wives' ratings corresponded significantly across time (convergent validity), and (d) topographical observational coding was associated with the experienced negative emotion intensity (convergent validity).

Dynamic (Time Series) Variables

We derived two variables to capture the dynamic influence of child negative affect and rule violations on maternal emotion: emotion dependence on negative affect and emotion dependence on rule violations. These variables were based on within-dyad time-series regression analyses in which maternal emotion in each 5-sec interval was predicted by past maternal emotion and then by negative affect or rule violations (considered separately).

The time-series analyses, based on Warner's (1992) methodological evaluation, involved several steps. First, linear and quadratic trends were removed from each time series (i.e., maternal emotion, child rule violations, child negative affect). This was done by saving the residuals of the regression of each time series on time and time-squared. Detrending each time series prior to analysis is necessary prior to assessing lagged relations between two series. A trend in a dependent variable over time can appear as the impact of an independent variable where none exists (McDowall, McCleary, Meidinger, & Hay, 1980) and can also obscure true relations. Thus, dynamic variables must be detrended prior to analysis by time-series methods.

Then, autoregressive effects were removed. Each residualized maternal emotion series was examined to see how many lagged terms were needed to account for autoregressive effects (serial correlation of mothers' present emotion from past emotion). Lagged emotion terms were added in sequence beginning with t – 1 (i.e., the mother's emotion from the previous 5-sec interval). Lagged maternal emotion terms were entered as predictors until the next higher order term was statistically nonsignificant (i.e., the significance of the t test for the regression coefficient exceeded .05). The number of significant lagged emotion terms ranged from two to five (mode = 2). A squared multiple correlation was calculated from the time-series regression containing lagged mother emotion terms to determine the degree to which a mother's emotion was predicted by systematic variation in her past emotion. In addition to being a required step in the time-series analyses, this served as our index of serial predictability of emotion in later analyses.

Next, one or more lagged child terms were added following the method used for mother emotion terms. Squared multiple correlation increments were calculated to determine how much the prediction of maternal emotion increased when lagged child terms were added to the equation that already included past maternal emotion. The “influences” of negative affect and rule violations were determined in separate series of regressions. The squared multiple correlation increments derived from these analyses served as emotion dependence variables in subsequent analyses. They represented the degree to which variations in prior negative affect and rule violations predicted variations in maternal emotion, controlling for prior systematic variations in maternal emotion. Although not a use of R2 that is typical in psychology, Warner's (1992) work suggests this use is sound.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Harshness, negative affect, emotion dependence on negative affect, and emotion dependence on rule violations were positively skewed. A log transformation of harshness and a square root transformation of negative affect successfully normalized them. Transformations did not normalize emotion dependence on negative affect and rule violations. We used S+ (version 6.1; Insightful Corporation, 2002) to screen these data using a test of bias resulting from the use of ordinary least squares estimation for each of the planned analyses. All bias tests were nonsignificant (ps > .324). Therefore, we used ordinary analyses throughout.

Means, standard deviations, ranges, and Ns for all variables in the analyses are reported in Table 1. Two mothers were dropped from analyses involving emotion due to technical difficulties with the rating dial. A third mother was dropped from these analyses because her dial data appeared to be random, as judged by an extremely low autoregressive R2 (.10); the next lowest was .73. Further, an additional seven dyads were omitted only from analyses involving emotion dependence on negative affect (remaining N = 30) because the children had fewer than 5 episodes (out of approximately 120 intervals) of negative affect. The near-zero variability of negative affect across the interaction in these children's data made it impossible to validly assess dynamic relations between negative affect and maternal emotion within the interaction. All children showed evidence of variability in rule violations. Basing all analyses on only these 30 dyads did not substantially change the pattern of results (i.e., two associations that are statistically significant at p < .05 with 37 dyads drop to marginal significance at p = .06 and .07; all other relations did not change). Therefore, the maximum number of possible participants was used in each analysis. Finally, reflecting the directionality of our hypotheses, zero-order and partial correlations were evaluated via one-tailed significance tests.

H1: Emotion Dependence on Aversive Child Behavior Is Positively Associated With Harsh and Lax Discipline

We hypothesized that mothers' emotion dependence is related to differences in their discipline. To test this, correlations of harshness and laxness with emotion dependence on (a) negative affect and (b) rule violations were calculated (see Table 2). The hypotheses were supported with respect to dependence on negative affect, r(30) = .36, p = .025, but not rule violations. Harshness had a marginally significant association with emotion dependence on rule violations, r(37) = .26, p = .062. A similar pattern was obtained with regard to laxness, which was positively associated with emotion dependence on negative affect, r(30) = .39, p = .016, and not significantly associated with emotion dependence on rule violations, r(37) = .04, p = .397. Thus, the emotion of mothers who practiced worse discipline, compared to other mothers, was influenced to a higher degree by their toddlers' negative affect.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Variables in the Analyses

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Harshnessa | — | 40 | ||||

| 2. Laxness | .66** | — | 40 | |||

| 3. Negative Maternal Emotion Intensity | .43** | .27 | — | 37 | ||

| 4. Emotion Dependence on Negative Affect | .36* | .39* | −.02 | — | 30 | |

| 5. Emotion Dependence on Rule Violations | .26 | .04 | .04 | .33* | — | 37 |

| 6. Serial Predictability of Emotion | −.31* | −.38* | .06 | −.52** | −.34* | 37 |

Log transformed; one-tailed significance reported.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

H2: Harsh and Lax Discipline Are Inversely Related to Serial Predictability of Emotion

Next, we tested our hypothesis that mothers' serial predictability of emotion is related to individual differences in discipline. The significant negative correlations of serial predictability with harshness, r(37) = −.31, p = .031, and laxness, r(37) = −.38, p = .010, supported this hypothesis. Thus, worse discipline was associated with maternal emotion experience that was less predictable from moment to moment.

The temporal pattern of emotion in mothers' who exhibited similar levels of serial dependency of emotion could theoretically take on many forms (see our earlier discussion). Therefore, the shapes of emotion plots with different amounts of serial dependency were qualitatively analyzed to identify predominant patterns. The emotion plots of mothers high in serial dependency were roughly shaped like high amplitude sine waves (Figure 2, panel A), though the speed of the oscillations varied among individuals. The plots of mothers low in serial dependency evidenced more random flutter. However, even these were not without evidence of regularity, as even the most random series had an R2 of .73. The oscillations of these mothers' emotion series were also fairly large and of variable speed.

H3: Negative Emotion Intensity Is Positively Associated With Harsh and Lax Discipline

We hypothesized that lax and harsh discipline is associated with negative maternal emotion intensity. Average negative maternal emotion was significantly correlated with harshness, r(37) = .43, p = .004, and marginally significantly associated with laxness, r(37) = .27, p = .055. Thus, mothers displaying more harsh and, tentatively, lax discipline experienced more negative emotion.

H4: Emotion Dependence and Serial Predictability of Emotion Predict Variance in Discipline That Is Nonredundant With Negative Emotion Intensity

Last, we hypothesized that emotion dependence and serial predictability predict discipline independent of the average intensity of negative maternal emotion. This was tested via partial correlations. Holding negative maternal emotion intensity constant, harsh and lax discipline (respectively) were associated with serial predictability, rps (37) = −.37 and −.41, ps < .05, and with emotion dependence on rule violations, rps (37) = .27 and .03, ns, and negative affect, rps (30) = .46 and .41, ps < .05, only in cases in which a significant correlation had been detected between each predictor and criterion. These results underscore the independence of mothers' emotion dynamics and intensity of negative emotion as predictors of discipline.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that laxness and harshness are greater in mothers whose emotion is more dependent on their children's negative affect during discipline encounters than mothers whose emotion is less dependent on children's negative affect, independent of average emotion intensity. It is perhaps not surprising that being on the affect schedule of a toddler is associated with poor discipline, given the relatively high rate of negative affect displays in toddlers during discipline encounters and the lability of their affect. It may be that the more dependent mothers' feelings are on their children's affect, the more their discipline is selected to control child affect (and therefore, their own emotion) rather than shape more appropriate behaviors.

Our own clinical observation of highly lax mothers is that many report feeling highly influenced by their children's affect. When their children are happy, they are happy. When their children are upset, they are upset. Their discipline strategies prioritize reducing their children's negative affect, perhaps in service of making themselves feel better.

With respect to harsh discipline, the link with mothers' emotion dependence on child negative affect may be a factor that contributes to the coercive, escalating process characteristic of behavior-problem boys and their mothers (Snyder, Edwards, McGraw, Kilgore, & Holton, 1994). Snyder et al. found that aggressive children's conflicts were characterized by both the mother and the son matching or exceeding the other's behavioral intensity, with the conflict ending via escalating behavior, whereas nonaggressive children's mothers did not respond to escalated behavior with their own escalation. Perhaps these comparison mothers' own experiences were not as driven by the changes in their sons' negativity.

Interestingly, although emotion dependence on child negative affect contributes to both harsh and lax discipline, emotion dependence on child rule violations was unrelated to either harsh or lax discipline, both in zero-order correlations and after controlling for average intensity of mothers' experienced emotion. Thus, mothers' emotional reactions to children's negative affect appear to have greater implications for their discipline style than their emotions in response to breaking rules. Humans appear to be biologically programmed to respond to infants' cries (Murray, 1979). Perhaps this results in child negative affect being a more aversive stimulus than rule violations, even though rule violations are seemingly more closely tied to discipline than child negative affect. It is also possible, however, that because rule violations were defined, in part, by the rules of the protocol, mothers' emotion reactions to these rule violations may not perfectly capture their emotion reactions to violations of their own rules at home. Therefore, conclusive interpretation of these potentially differential findings awaits extension.

Our data suggest that the serial predictability of mothers' emotion may also be important for competent discipline. Higher levels of apparently random fluctuation in maternal emotion are suggestive of poorer emotion regulation. Regulation of emotion is viewed as essential for parenting (Dix, 1991). Less patterned emotion changes may undermine organized responses to aversive toddler behavior, making both harsh and lax responses more likely. Qualitatively, highly predictable emotion showed evidence of regular rises and falls over a wide range of emotion. Thus, highly regulated emotion was not “stable” per se but predictable. Furthermore, serial predictability was not associated with emotion intensity. Thus, highly predictable emotion appears to be adaptive for discipline, even if its mean level is negative.

Serial predictability is likely the end result of multiple regulatory processes influencing mothers' experiences at a variety of points in the temporal chain of emotion reactions (see Thompson, 1994). Its inverse associations with child influence variables suggest that a portion of the variance in serial predictability is likely internally regulated, perhaps via consciously controlled attempts to lessen negative emotion triggered at certain thresholds in some mothers or automatic and cyclical biochemical or metabolic processes. Both of these possibilities would result in the regular wave-like patterns noted in the plots. However, high serial predictability of emotion does not necessarily imply that the source of the emotion regulation is internal. For example, a highly predictable temperature pattern could be due to a working mechanical thermostat (internal control) or to the fact that a person is turning heating and cooling off and on in response to temperature changes (external control). Given that the serial predictability seems to be a nonspecific factor in adaptive discipline, efforts to further unpack this variable seem warranted.

Replicating previous findings (e.g., Smith & O'Leary, 1995), our findings suggest that the intensity of mothers' experienced negative emotion over the course of a discipline encounter is linked with harsh discipline. A more equivocal picture emerges with respect to laxness because the bivariate laxness–emotion association reported herein was marginal, and laxness and experienced emotion were not significantly associated in a previous study (Smith & O'Leary, 1995). Thus, maternal negative experienced emotion does not appear to be a strong or consistent correlate of laxness. Perhaps the laxness–negative emotion relation might be expected to be weak if lax parenting reflects a reaction to negative emotion (as hypothesized) for some parents and emotional disengagement for others.

Limitations

The video-mediated recall method of assessing mothers' experience of emotion used in this investigation relied on mothers' accurate reliving or recollection and reporting of emotions they experienced during the interactions with their toddlers. Although there are data from the marital literature supporting the validity of this type of measure (Gottman & Levenson, 1985), it is likely that these procedures introduce some error. Assessing emotion experience on a moment-by-moment basis during an interaction would substantially disrupt the interaction, thereby reducing the validity of both the observed behavior and the emotion experienced. Other channels of emotion (e.g., physiology) could potentially be assessed with less impact on the interaction. Integrating both physiology and video-mediated recall ratings could perhaps provide the strongest design, as these two experience measures could address the validity of each other.

Sample composition is another limitation. The sample comprised a small group of Caucasian, middle-class, volunteer mothers who responded to print advertisements. The demographic characteristics of this sample were fairly typical of the suburban county in which they resided. Notwithstanding, unmeasured differences related to reading and responding to print advertisements, and being willing to volunteer for the study, could have influenced the findings. Certainly, the generalizability of the findings to other populations (e.g., lower socioeconomic status, non-Caucasian families) is also questionable and merits further study. These factors, combined with the small sample size, suggest caution when generalizing the findings.

Finally, this is a novel, and we think promising, method for studying emotion dynamics. Time-series approaches, although rare in psychology, are very typical in other social sciences, and their applicability to understanding social interaction has been the subject of quantitative evaluation (Warner, 1992). That said, the analytic approach we used is sensitive to not only the generalizability of the sample, but also to the behavioral observations analyzed. Thus, the proportions of variance accounted for in the time-series variables and their relations should not be generalized to other contexts and samples without further study. Further, as with all relatively new applications of techniques, its strengths and weaknesses are probably not currently fully understood. As the use of time series to study dyadic processes becomes more widespread, we should take care to further evaluate this application of time-series techniques.

Theoretical Implications

Our findings indicate the usefulness of considering emotion dynamics in models of emotion and discipline. Importantly, emotion dynamics provide prediction of discipline that is independent of average negative affect intensity, tapping distinct aspects of mothers' emotional functioning. Thus, these variables contribute uniquely to models of discipline. Emotion dynamics might also relate to other parenting constructs of interest, thereby contributing to more global multivariate models of parenting. Perhaps, outside of discipline encounters, high levels of maternal emotion dependence enhance maternal warmth and responsivity, as a mother's attention is directed at maintaining her child's happiness.

Despite Dix's (1991) call for a transactional approach to the study of parents' emotion, emotion dynamics in parent–child interaction are understudied, and we believe that ours is the first study to include both experienced emotion and discipline. A transactional approach suggests microlevel bidirectional influence between parent and child emotions. Because we focused on mothers' experience of emotion, our data only examined one direction of influence: from child to parent. Other studies suggest that young children's expressed emotion can be influenced by mothers' outward reactions (e.g., Feldman et al., 1999). Optimally, models of emotion dynamics in parent–child dyads should strive to incorporate both directions of influence.

Further, placing our findings within the context of the existing literature suggests that it may be important to consider both affective expression and experience in our models of emotion and parenting, as they may operate somewhat independently (Martin et al., 2002). Future studies in which the dynamics of mothers' emotion expressions are investigated might answer questions about the generalizability of our findings to different channels of emotion, perhaps increasing our understanding of emotion in parenting.

Our results also suggest that emotion dependence on different types of aversive child behavior may not be equally important to discipline. Mothers' emotion dependence on children's rule violations did not relate to discipline, whereas dependence on children's negative affect did. These findings suggest that emotion dependence should not be considered outside of the context of what the emotions are dependent on. As work in this area progresses, isolating important matches between type of input (e.g., child negative affect) and behavioral correlates (e.g., discipline) will likely be critical to our efforts at understanding the role of parents' emotion dynamics. Finally, ideas about emotion dynamics of the type explored in this article may be relevant to understanding how specific emotions (e.g., sadness, happiness) function during parent–child interactions and relate to other important parenting practices and child outcomes.

As we progress in this area, it is critical that we carefully consider what other variables may contribute to parents' emotion dynamics. It seems likely that factors we know relate to parents' emotion and behavior, such as perceptions of child behavior (e.g., Lorber et al., 2003) and attributions of child intent (e.g., Slep & O'Leary, 1998), may account for additional variance in emotion dynamics or even moderate the relation between child behavior and emotion dynamics. Further, it seems likely that contextual factors might affect emotion dynamics by increasing dependence on child negative affect (e.g., time pressure, competing demands).

Ultimately, understanding the role of emotion dynamics in dysfunctional behavioral processes between parents and children (e.g., Snyder & Patterson, 1995) may enable the field to enhance the impact of parenting interventions. In contrast to the great deal of literature on parent–child interaction sequences that are the cornerstone for behavioral parenting interventions, how emotion functions to facilitate or inhibit these sequences is a relatively new area of inquiry. As theory and the empirical database on maternal emotion dynamics grow, the links between dysfunctional behavior and maladaptive emotion regulation may prove to be fruitful intervention targets.

Footnotes

Michael Lorber is now at the Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota. Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH67043. Portions of this article were presented at the 36th Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy Convention in Reno, NV, November 2002.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EH, O'Leary SG. The effect of child negative affect on maternal discipline behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:585–595. doi: 10.1007/BF01447663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O'Leary SG, Wolff L, Acker MM. The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Strongman KT, Magai C. Emotions and behaviour: Data from a cross-cultural recognition study. Cognition and Emotion. 2003;17:881–902. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Workman E, Cole PM, Weissbrod C, Kendziora KT, Zahn-Waxler C. Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:23–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Ruble DN, Grusec JE, Nixon S. Social cognition in parents: Inferential and affective reactions to children of three age levels. Child Development. 1986;57:879–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdney L, Pickles AR. Expression of negative affect with disciplinary encounters: Is there dyadic reciprocity? Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:606–617. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Wekerle C. Maternal reports of child behavior problems and personal distress as predictors of dysfunctional parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P. Are there basic emotions? Psychological Review. 1992;99:550–553. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Greenbaum CW, Yirmiya N. Mother–infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:223–231. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodi AM, Lamb ME. Child abusers' responses to infant smiles and cries. Child Development. 1980;51:238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Levenson RW. A valid procedure for obtaining self-report of affect in marital interaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:151–160. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. The psychology of emotions. Plenum; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kendziora KT, O'Leary SG. Dysfunctional parenting as a focus for prevention and treatment of child behavior problems. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;15:175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW. Human emotions: A functional view. In: Ekman P, Davidson RJ, editors. The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1994. pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Gottman JM. Marital interaction: Physiological linkage and affective exchange. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:587–597. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.45.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, O'Leary SG, Kendziora KT. Mothers' overreactive discipline and their encoding and appraisals of toddler behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:485–494. doi: 10.1023/a:1025496914522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SE, Clements ML, Crnic KA. Maternal emotions during mother–toddler interaction: Parenting in an affective context. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall D, McCleary R, Meidinger E, Hay RA. Interrupted time series analysis. Sage; London: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Murray AD. Infant crying as an elicitor of parental behavior: An examination of two models. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:91–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WL, Strayer J. Parents' responses to the emotional distress of their children: Relations with children's competence. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Insightful Corporation. (2002). S+ (Version 6.1) [Computer software]. Seattle, WA: Author

- Slep AMS, O'Leary SG. The effects of maternal attributions on parenting: An experimental analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, O'Leary SG. Attributions and arousal as predictors of maternal discipline. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19:459–471. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Edwards P, McGraw K, Kilgore K, Holton A. Escalation and reinforcement in mother–child conflict: Social processes associated with the development of physical aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JJ, Patterson GR. Individual differences in social aggression: A test of a reinforcement model of socialization in the natural environment. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 59. 1994. pp. 25–52. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner RM. Sequential analysis of social interaction: Assessing internal versus social determinants of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ. Interrater agreement for journal manuscript reviews. American Psychologist. 1984;39:22–28. [Google Scholar]