Abstract

Zonula occludens (ZO)-1 was the first tight junction protein to be cloned and has been implicated as an important scaffold protein. It contains multiple domains that bind a diverse set of junction proteins. However, the molecular functions of ZO-1 and related proteins such as ZO-2 and ZO-3 have remained unclear. We now show that gene silencing of ZO-1 causes a delay of ∼3 h in tight junction formation in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells, but mature junctions seem functionally normal even in the continuing absence of ZO-1. Depletion of ZO-2, cingulin, or occludin, proteins that can interact with ZO-1, had no discernible effects on tight junctions. Rescue of junction assembly using murine ZO-1 mutants demonstrated that the ZO-1 C terminus is neither necessary nor sufficient for normal assembly. Moreover, mutation of the PDZ1 domain did not block rescue. However, point mutations in the Src homology 3 (SH3) domain almost completely prevented rescue. Surprisingly, the isolated SH3 domain of ZO-1 could also rescue junction assembly. These data reveal an unexpected function for the SH3 domain of ZO-1 in regulating tight junction assembly in epithelial cells and show that cingulin, occludin, or ZO-2 are not limiting for junction assembly in MDCK monolayers.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelia form the archetypal polarized tissue of the Metazoa (Knust and Bossinger, 2002; Gibson and Perrimon, 2003; Nelson, 2003). Typically, they create a barrier between the extracellular environment and the interior of the organism. Epithelia organize into layered sheets of cells with apical-basal polarity and strong cell-cell adhesions. The tight junction is the most apical adhesion between epithelial cells and is a complex structure that functions both as a barrier to the paracellular diffusion of ions and molecules and as a fence to separate the apical plasma membrane from the basolateral domain in polarized epithelia (D'Atri and Citi, 2002; Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003; Matter and Balda, 2003). Tight junctions are fine-tuned to perform specific functions in different tissues and respond dynamically to changes in the environment and cell density (Tsukita and Furuse, 2002). The junctions between epithelial cells bear structural and functional relationships to endothelial cell junctions, neuromuscular junctions, and both immune and neural synapses. Similar proteins are present in all of these structures, and the same conserved groups of polarity proteins drive their formation. It is therefore important to understand the fundamental structural basis for tight junction formation and to learn the rules for their assembly.

Tight junctions contain at least 40 different proteins (Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003). Some of these proteins, such as the claudins and occludin are transmembrane proteins that form intercellular homophilic and heterophilic adhesions, whereas others such as ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, cingulin, MAGI-1, Pals1, and PATJ are intracellular plaque proteins that form a scaffold between the transmembrane proteins and the actin cytoskeleton. Certain of these proteins also engage in feedback regulation of gene expression. For example, ZO-1 can bind through its Src homology 3 (SH3) domain to a transcription factor called ZONAB, which controls epithelial cell proliferation (Balda and Matter, 2000; Balda et al., 2003). As epithelial cells differentiate and become more polarized, ZO-1 levels at the junctions increase, sequestering more ZONAB to the junctions and away from the nucleus, thereby repressing proliferation.

Polarity proteins such as Par-3, Par-6, aPKC, and Pals1 also localize to tight junctions, and in some cases, they have been shown to be essential for their normal assembly (Ohno, 2001; Chen and Macara, 2005; Shin et al., 2005). These same proteins are required for the polarization of diverse cell types, including neurons and astrocytes, the nematode zygote, fly neuroblasts and oocytes, endothelial cells, and T-lymphocytes (Nelson, 2003; Macara, 2004). Nonetheless, almost nothing is known about the basic steps in tight junction assembly. We do not know what most of the polarity proteins do, which proteins define the location of the junctions, or the order of assembly of the various junction components, or the structure of a junctional unit, or how these units link into a concatenated chain that encircles each epithelial cell. One problem is that many of the structural components of the tight junction are large, complex proteins with diverse domains of uncertain function. Junctions contain many MAGUK proteins, each of which possesses PSD-95, Discs large, ZO-1 (PDZ), SH3, and guanylate kinase-like (GUK) domains (Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003; Funke et al., 2004). ZO-1, for example, contains three PDZ domains, which have been reported to bind to claudins, ZO-2, connexin36, and the junctional adhesion molecule-1 (Itoh et al., 1999; Ebnet et al., 2000; Li et al., 2004). The SH3 domain binds an unknown protein kinase, and to a transcription factor, ZONAB (Balda et al., 1996; Balda and Matter, 2000). An acidic sequence adjacent to the SH3 domain has been reported to bind to heterotrimeric G proteins; the GUK domain binds occludin (Furuse et al., 1994; Fanning et al., 1998); and the C terminus can bind actin, cortactin, and protein 4.1 (Fanning et al., 1998; Katsube et al., 1998; Meyer et al., 2002). ZO-1 can also associate with a coiled-coil protein called cingulin (Cordenonsi et al., 1999). However, it is unclear which, if any, of these domains and binding partners are important for the biological functions of ZO-1. Disruption of the occludin and cingulin genes in embryoid bodies derived from embryonic stem cells did not prevent tight junction formation (Saitou et al., 1998; Guillemot et al., 2004). Moreover, a comprehensive analysis of junctional complexes using density gradient fractionation found little association of ZO-1 with either occludin or claudins (Vogelmann and Nelson, 2005).

A knockout of ZO-1 in mouse epithelial cells recently demonstrated that ZO-1 is not essential for tight junction formation but that loss of ZO-1 causes a pronounced delay in junction assembly, as measured after withdrawal and replacement of calcium in the medium (Umeda et al., 2004). We now show that gene silencing of ZO-1 in canine MDCK epithelial cells by RNA interference (RNAi) causes the same phenotype and that the delay occurs at least in part during the initial spreading phase after the calcium switch, and during remodeling of the apical ring as cells form contacts with one another. We used rescue experiments with mouse ZO-1 to demonstrate that the SH3 is a key determinant for junction assembly, whereas the PDZ1 domain and C-terminal region seem to be nonessential. Several ZO-1 binding proteins, including occludin, ZO-2, and cingulin, lack detectable function in tight junction assembly, under the conditions of our experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of ZO-1 Mutants

Point mutations were introduced into the α- isoform of murine ZO-1 using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). To create the PDZ domain mutation, R28 was mutated to a glutamate. The SH3 domain mutation was introduced into the ligand binding pocket by changing W557 and L558 to glycine and alanine, respectively. An EcoRV site is present at base 1999, close to the beginning of the GUK domain; so point mutations were introduced near the 3′ end of the sequence that encodes the domain to create a second EcoRV restriction site that would retain the correct frame after digestion to remove the intervening sequence. The mutations were CGATT→ATATC (residues 2366-2370). Each of the mutant ZO-1 constructs was generated in pBluescript and then subcloned into the pK-YFP vector (Du and Macara, 2004). A C-terminal fragment of ZO-1, encoding residues 893-1666, was obtained by PCR and ligated into pKH3. The 1523 amino acid C-terminal truncation of ZO-1 was produced by digesting pK-YFP-ZO-1 with ClaI and inserting a linker that contained a stop codon. The presence of a unique Cla1 site 3′ to the ZO-1 open reading frame (ORF) allowed removal of the C-terminal tail of ZO-1. Sequences encoding the isolated SH3 domains of ZO-1 and p120RasGAP were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pK-YFP. (A schematic of the mutants is shown in Figure 6A.)

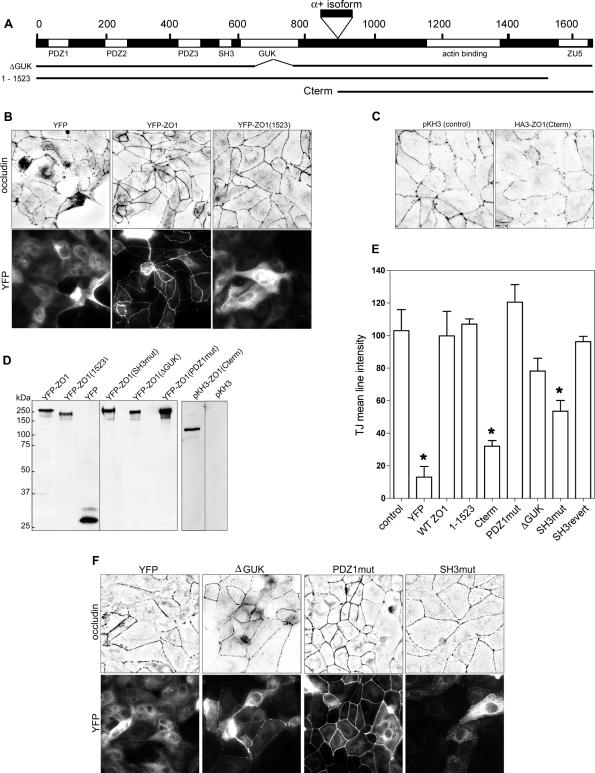

Figure 6.

Rescue of tight junction assembly by mutants of murine ZO-1. (A) Schematic of ZO-1 showing domains and deletion mutants. (B) Cells were transfected with shRNAs against the canine ZO-1 together with vectors that express YFP, YFP-mZO-1, or YFP fusions of murine ZO-1 fragments. Calcium was withdrawn after 2 d and then readded 18 h later. After a further 3 h, the cells were fixed and stained with antibodies to occludin and GFP. Images were processed as described in Figure 2. (C) Cells were transfected as described in B but with a vector encoding the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged C terminus of ZO-1, subjected to calcium switch as described in A, and stained for occludin. (D) Cell lysates were blotted with anti-GFP or anti-HA antibodies. (E) Images were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods to quantify the pixel intensity along cell-cell boundaries. Mean pixel values are shown for each treatment ± 1 SD (n = 3 fields). Asterisks show values that are significantly different (p < 0.05) from both the control and the wild-type rescue, as evaluated using an unpaired, two-tailed t test. (F) Cells were transfected as described in A but together with mutant versions of YFP-mZO-1 and were analyzed as described in A and D.

Cell Culture and Transfection

The MDCK canine epithelial cells (T-23 line) used in these experiments were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin, streptomycin, and 1% sodium pyruvate. Gene silencing was performed using the pSUPER vector as described previously (Chen and Macara, 2005). Canine DNA data were obtained from GenBank, and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting sequences were chosen using the Dharmacon Web site (http://dharmacon.com/siDESIGN/). Two shRNAs were designed for each gene (Table 1). Cells were transiently transfected using an electroporation technique (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD). In total, 3-5 μg of DNA was electroporated into 2 × 106 cells.

Table 1.

Small interfering RNA sequences used for knockdowns

| Gene name | pSUPER vector | Target sequence |

|---|---|---|

| ZO-1 | pS-ZO1a | AACGGTCACTCCAGCATAT |

| pS-ZO1b | GATATTGTTCGGTCTAATC | |

| ZO-2 | pS-ZO2a | GCAGCAGTATTCCGACTAT |

| pS-ZO2b | GCAGGATCCGAGAAATCTA | |

| Occludin | pS-OCCa | TGGTAAAGTGAATGACAAG |

| pS-OCCb | AGAGGAATTATTGCAAGCA | |

| Cingulin | pS-CINGa | GAACAAGGATGAACTTAGA |

| pS-CINGb | GCAACATGAGGTCAATGAA |

For calcium switch experiments, the cells (∼1 × 106/35-mm dish) were allowed to grow for 2 d posttransfection. Cells were then rinsed with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the medium was changed to minimum essential medium lacking calcium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated FCS that had been dialyzed against the same medium, plus penicillin and streptomycin. The following morning, the calcium-free medium was replaced by normal medium with serum.

Immunofluorescence/Immunoblotting

Transfected cells were plated on eight-well Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL). Approximately 4 × 105 cells were plated in each well. The remaining transfected cells were plated on 35-mm tissue culture dishes (Corning, Corning, NY) and used for immunoblotting to determine expression levels.

Cells were fixed using a 1:1 mixture of ice-cold methanol/acetone for 3 min, blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 3% bovine serum albumin/phosphate-buffered saline followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature with anti-occludin monoclonal (1:500 dilution from 1 mg/ml; Invitrogen), and anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) polyclonal antibodies (1:500, 2 mg/ml; Invitrogen). ZO-1 was stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:500, 0.25 mg/ml; Invitrogen). After a brief wash in PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa 594 anti-mouse and Alexa 488 anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:2000, 2 mg/ml; Invitrogen) for 1 h. The slides were mounted using 22 × 50-mm coverglasses (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and gel/mount aqueous mounting medium (Biomeda, Foster City, CA) and sealed with a coat of clear nail polish. Slides were viewed on a Nikon Eclipse inverted microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu Orca charge-coupled device camera (C4742-95-12NRB) and a 60× water immersion lens (numerical aperture [N.A.] 1.2). Images were collected at 12-bit depth with 1 × 1 binning, using Openlab software (Improvision, Boston, MA), and processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0. Confocal images were collected using a Zeiss LSM510 META microscope, with a 100× oil-immersion lens (N.A. 1.3) and rendered with Volocity software (Improvision).

For immunoblotting, cells were scraped into 250 μl of lysis buffer (0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and brought to a final volume in PBS). A fraction was removed for protein quantification by the Bradford assay, and then Laemmli buffer was added to the remainder, and they were boiled for 3 min. Proteins were separated by SDS PAGE on an 8% gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. Primary antibodies were rabbit polyclonals for ZO-1, ZO-2, claudin1, (1:1000, 0.25 mg/ml; Invitrogen), cingulin anti-serum (1:1000; Invitrogen), anti-E-cadherin monoclonal (1:2500, 0.25 mg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), anti-GFP polyclonal (1:500, 2 mg/ml; Invitrogen), and cortactin hybridoma supernatant (clone 4F11; a kind gift of Tom Parsons, University of Virginia, Charlottesville,VA). After incubation with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:20,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), bands were visualized using chemiluminescent reagents (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD).

Image Processing

To improve the visualization of junction formation, images were processed in Adobe Photoshop by enhancing the contrast, and then inverting the pixel values, so that the junctions show up as black lines on a white background. To provide a more objective measure of junction assembly rescue, we developed a measure of junction staining integrity. Briefly, cell-cell boundaries were traced for a series of the images showing occludin staining, using ImageJ, which generates a value between 0 and 255 for each pixel along the traced line. We found it easiest to track cell boundaries in a continuous line from one edge of the image field to the other. We traced at least three such lines for each image, which collects data on the junctions for ∼10-15 cells. The mean pixel value was then calculated for all the traces in each image. In the absence of any detectable occludin at the boundaries, or at gaps in the junctions, the mean intensity value was close to zero (white pixels). For control cells with intact junctions, with no gaps, it was close to 140. Values from multiple images and experiments were pooled to obtain means and SEs and were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed t test.

Transepithelial Resistance Measurements

Cells (∼1 × 106) were plated and grown for 2 d on 12-mm Costar Transwell filters (0.4-μm pore size) to form confluent monolayers. They were depleted of calcium overnight. The resistance across the monolayers was measured, after readdition of calcium-containing medium, using an EVOM (WPI, Sarasota, FL). An empty filter was used to determine the background resistance. Three separate filters were used for each condition, and the mean resistance was calculated after background subtraction, in ohms · cm2 (Matter and Balda, 2003).

Time-Lapse Microscopy

Cells were transfected with pK-YFP-occludin or pK-YFP-ZO-1 and plated on Lab-Tek 4-well coverglasses. They were switched to calcium-free medium after 2 d, and then mounted on a Zeiss Axiophot inverted microscope and maintained at 37°C with a Nevek incubator system. The cells were switched to F-12 medium (with calcium) plus 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, plus Oxyrase (0.3 units/ml) to reduce phototoxicity. F-12 has lower background fluorescence than DMEM. Images (12-bit grayscale) were collected using a 40× objective lens (N.A. 0.95), with the mercury lamp at 50% power, and with a 34% neutral density filter in the excitation path. The frame-rate was 1/min. The YFP-ZO-1 cells were also imaged using a PerkinElmer spinning disk confocal microscope, at a frame rate of 0.5/min. Stacks of 10 images were collected at each time point, and each stack was flattened and processed using Volocity software. The movies were then converted to 8-bit and processed in Photoshop to enhance contrast.

RESULTS

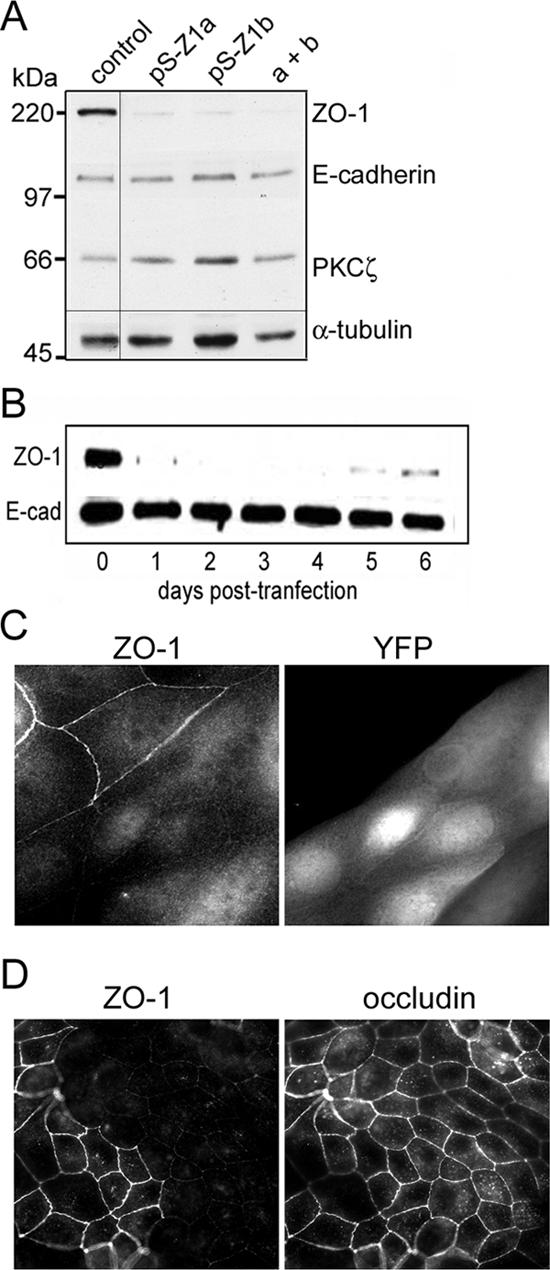

Efficient and Persistent Gene Silencing of ZO-1 in MDCK Cells

Gene silencing was performed by transient transfection using the pSUPER vector to express shRNAs targeting the canine ZO-1 open reading frame (Brummelkamp et al., 2002). Two distinct sequences were chosen, each of which differs from the corresponding DNA sequence of murine ZO-1 by at least two nucleotides. Both shRNAs efficiently knocked down expression of the endogenous ZO-1 in MDCK cells, without altering the expression of other proteins, including E-cadherin and atypical protein kinase C (PKC)ζ (Figure 1A). The ZO-1 level was reproducibly reduced by at least 90%. Gene silencing was most efficient with a mix of the two pSUPER constructs and so was used for most of the experiments described below. Loss of ZO-1 was apparent within 24 h, and persisted for almost a week (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Efficient gene silencing of ZO-1 in MDCK cells using shRNAs. (A) Immunoblot showing depletion of ZO-1 protein by two unrelated shRNAs targeting canine ZO-1 mRNA. Cell lysates were prepared 3 d posttransfection, and equal amounts of protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Blot was probed sequentially for ZO-1, E-cadherin, and PKCζ, and for tubulin as a loading control (note all lanes were from the same gel and blotted together; an intervening empty lane was deleted from the final image). (B) Silencing of ZO-1 is rapid and persists for at least 5 d posttransfection. E-cadherin was used as a loading control. (C) Depletion of ZO-1 does not cause obvious tight junction defects. Cells were cotransfected with the mixed pSUPER vectors (pS-Z1a and pS-Z1b) against ZO-1 plus YFP as a marker. After 3 d, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde and stained for ZO-1, or were fixed in methanol and stained for ZO-1 and occludin (D, bottom). Regions were selected that contained a mix of transfected and untransfected cells. Images were collected using a 63× water immersion objective (N.A. 1.2), and processed in Adobe Photoshop.

Cells were next transfected with the pSUPER constructs together with a plasmid that expresses yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), as a transfection marker. After 3 d, cells were fixed and examined by immunofluorescence for ZO-1. Staining was greatly reduced from the cell junctions specifically in those cells that expressed the YFP marker (Figure 1C). Some residual staining in the nucleus and cytoplasm seems to be nonspecific. In agreement with the observations by Umeda and colleagues of murine epithelial cells that lack ZO-1 (Umeda et al., 2004), the silencing of ZO-1 expression did not cause any apparent defect in the tight junctions of polarized MDCK cells, as determined by staining for occludin (Figure 1D). Confocal z-stacks showed that the occludin remained apical and was indistinguishable in location between cells depleted of ZO-1 and control cells (Supplemental Figure S1).

Loss of ZO-1 Causes a Delay in Junction Assembly after Calcium Switch or Replating

To determine whether ZO-1 is required for normal junction assembly, cells were cotransfected with pSUPER or with the pSUPER-ZO-1 constructs plus the YFP vector, and then after 2 d were switched to a medium lacking calcium. Under these conditions, the E-cadherin interactions are lost, and the cells withdraw from one another (Matter and Balda, 2003). The next day, the cells were switched back to medium containing normal medium and then were fixed at intervals and stained for either occludin or claudin-1 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

ZO-1 depletion causes a delay in tight junction assembly and function. (A) Cells were transfected with empty pSUPER or with vector that expresses shRNAs against ZO-1 and plated on eight-well Lab-Tek slides. After 2 d, the cells in all but one well of each slide (NS) were switched to a calcium-free medium and incubated overnight. After readdition of normal medium containing calcium, cells were fixed at intervals and stained for occludin or claudin-1. Images were collected as in Figure 1. They were postprocessed to emphasize the junctions by performing an unsharp mask to reduce haze and then inverting pixels to make the junctions black-on-white, and enhancing the contrast. (B) Images were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods to quantify the pixel intensity along cell-cell boundaries. Occludin staining at the boundaries increases the mean pixel values. Three lines were traced along boundaries from edge to edge. The boundary length for each line was ∼3000 pixels. A high mean value corresponds to strong occludin staining. (C) Cells were transfected as described in A and plated onto 12-mm filters (0.4-μm pores). Calcium switch was performed as described in A, and the transepithelial resistance (TER) was measured at intervals. (D) Cells were transfected as described in A and then grown on 100-mm plates for 3 d. The cells were then trypsinized and replated onto collagen-coated coverglasses. At intervals, the cells were fixed and stained for occludin. Images were obtained and processed as described in B.

In the control cells, occludin and claudin are initially concentrated in spots (presumably vesicles) within the cell bodies (Ivanov et al., 2004b), but they localize to the boundaries and form unbroken lines within 120 min after calcium replacement (Figure 2A). In cells lacking ZO-1, however, there is a pronounced delay in the accumulation of these proteins at boundaries, and they accumulate as broken lines that do not fuse into a continuous border around each cell. A similar phenotype was reported by Umeda et al. (2004) for Eph-4 cells from which the ZO-1 gene has been deleted. The quantitation of occludin at the cell boundaries showed, however, that once the junctions have started to form, the rate of assembly seems to be similar to that of control cells (Figure 2B).

To determine the functional consequences of the delay in junction assembly caused by loss of ZO-1, we measured the transepithelial resistance of MDCK cell monolayers grown on filters. Typically, our MDCK II cells exhibit a rapid increase in resistance, which peaks at ∼6-8 h. The resistance then gradually falls until it reaches a stable value of ∼100 ohms (Figure 2C). The molecular basis for this behavior is unknown. Interestingly, however, the silencing of ZO-1 expression abolishes the initial peak in transepithelial resistance, although by 6 h postcalcium switch the tight junctions seem to be morphologically almost normal as judged by staining for occludin (Figure 2C). By 24 h the resistance is the same irrespective of ZO-1 expression.

It seemed possible that the defect in cells lacking ZO-1 might be specific to the effects of calcium depletion, rather than to a fundamental change in the kinetics of junction assembly. Therefore, we trypsinized cells and replated them at high density onto collagen-coated slides. As shown in Figure 2D, within 6 h of replating, the normal cells had established junctions as assessed by occludin staining, whereas the cells lacking ZO-1 had not. Thus, the defect caused by silencing of ZO-1 expression is independent of the technique used to disrupt and permit junction assembly.

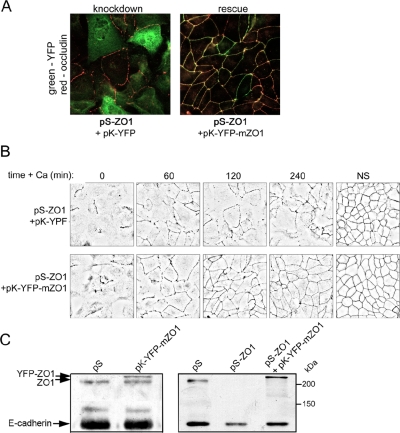

Junction Assembly Can Be Rescued by Expression of Murine ZO-1

To confirm that the delay in tight junction assembly is caused by loss of ZO-1 rather than by off-target effects of the shRNAs, we coexpressed murine ZO-1 as a YFP fusion protein together with the pSUPER-ZO-1 constructs. We used the α- isoform of ZO-1 that lacks a 240-base pairs insert at position 2713 (see diagram, Figure 6A) (Willott et al., 1992; Balda and Anderson, 1993). This YFP-ZO-1 was targeted correctly to cell boundaries and efficiently rescued the formation of tight junctions as assessed by occludin staining (Figure 3A). Additionally, the presence of murine YFP-ZO-1 restored the normal time course for junction assembly (Figure 3B). When expressed in normal MDCK cells, the level of YFP-ZO-1 was comparable with that of the endogenous protein (Figure 3C). Note that the transfection efficiency was ∼75%, for visible expression of the fluorescent fusion protein. Importantly, the rescue of junction assembly was not caused by reexpression of the endogenous ZO-1 in cells transfected with the pK-YFP-ZO-1 vector (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Murine ZO-1 tagged with YFP can rescue junction formation in MDCK cells depleted of endogenous ZO-1. (A) Cells were transfected with the pSUPER constructs against canine ZO-1 plus vectors that express either YFP alone or a YFP-mZO-1 fusion protein. After 2 d, calcium was withdrawn from the medium for 18 h and then added back for 3 h before fixation with methanol and staining with antibodies against GFP and occludin. (B) Cells were prepared as described in A and then calcium was added back for the indicated times before fixation and staining for occludin. Images were processed as in Figure 2. (C) Cells were transfected and grown on filters as in Figure 2B and then subjected to a calcium switch. The transepithelial resistance was measured at intervals after calcium readdition. (D) The level of YFP-ZO-1 expression was estimated by transfecting cells with the appropriate vector and then immunoblotting cell lysates for ZO-1. The top band is the YFP fusion and the bottom band is the endogenous ZO-1 protein. E-cadherin was used as a loading control. Immunoblotting was also performed on lysates from cells transfected with shRNAs against ZO-1.

Time-Lapse Imaging of Junction Assembly Using YFP-Occludin and YFP-ZO-1

To identify more precisely the defect in junction formation caused by depletion of ZO-1, we used a YFP-occludin fusion as a junction marker. The YFP-occludin localizes correctly to tight junctions and has no apparent effect on the development of transepithelial resistance after a calcium switch. A similar construct has been used previously to follow junction formation in murine epithelial cells (Ando-Akatsuka et al., 1999). We think, therefore, that it is a suitable marker to track junction assembly. Cells were cotransfected with the control pSUPER or ZO-1 pSUPERs together with the YFP-occludin vector. After 2 d, calcium was withdrawn. Sixteen hours later, the cells were mounted on a microscope and imaged at a rate of 1 frame/min.

As shown in Figure 4 and Supplemental Video 1, the YFP-occludin in most cells is initially organized into a ring, within which are multiple spots. This ring coincides with actin and ZO-1, in fixed cells stained with phalloidin or anti-ZO-1 antibodies (our unpublished data). The structure is very similar to the apical ring observed in intestinal epithelial cells that express high levels of active LKB1 (Baas et al., 2004). Similar rings are also observed during the disassembly of junctions after calcium withdrawal from T84 epithelial cells (Ivanov et al., 2004a). It likely defines an apical surface that survives even when the cells do not contact one another. Interestingly, upon addition of calcium, the cells quickly begin to extend lamellipodia-like extensions. When these touch neighboring cells, the YFP-occludin ring disintegrates. The spots are no longer corralled and can spread throughout the cytoplasm. Also, shortly after the loss of the apical ring, broken lines of YFP-occludin occur between adjacent cells, which spread and consolidate into continuous junctional lines. (A diagram of these events is shown in Figure 8.) We did not observe the bright spots fusing with the junctions, but over the longer term, we assume that this material is incorporated into the junctions, because in cells with mature junctions such spots are no longer visible.

Figure 4.

Time-lapse imaging of YFP-occludin during tight junction assembly. Cells were transfected with pK-YFP-occludin and plated on Lab-Tek coverglass chambers. After 2 d, the cells were switched to a calcium-free medium. After a further 16 h, the cells were mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert fluorescence microscope and imaged using a 40× (N.A. 0.95) objective. An incubator maintained the cells at 37°C. The medium was replaced by prewarmed F-12 medium containing calcium, 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, and Oxyrase (to reduce phototoxicity). Images were collected at a rate of 1 frame/min for ∼1 h and processed in Photoshop to increase contrast.

Figure 8.

A model for tight junction assembly after calcium switch. This model is based on the time-lapse images shown in Figure 4. In control cells actin and tight junction components such as occludin are concentrated in an apical ring, and in vesicles that seem to be corralled within the ring. On addition of calcium the cells extend lamellipodia. The ring remains intact for ∼10-30 min, until cells make contact with one another, after which it suddenly disintegrates, and the vesicles spread throughout the cytoplasm. Junctional spots begin to form at the cell-cell boundaries and rapidly become consolidated into bands that encircle each cell. In cells depleted of ZO-1, these events occur more slowly, and usually the apical ring does not disintegrate.

To confirm that this behavior was not peculiar to YFP-occludin, we also made movies of YFP-ZO-1 in MDCK cells after a calcium switch. As shown in Supplemental Figure S2, the ZO-1 is organized into apical rings at early times, with several bright spots corralled within the rings. Within 8-20 min after calcium addition, the rings disintegrate and begin to reform at the cell periphery, where contact has been made with neighboring cells. The ZO-1 patches at the periphery spread and fuse to form a continuous band around each cell.

The behavior of YFP-occludin in cells depleted of ZO-1 is quite different (Figure 4 and Supplemental Video 2). The cells seem much less dynamic. They do not spread as rapidly, and the apical ring usually remains intact or begins to disintegrate much later than is usual in the control cells. Often, the ring slowly expands until it seems to make contact with neighboring cells. Because cell spreading requires extensive actin remodeling, we speculate that gene silencing of ZO-1 might cause an early defect in actin dynamics when the cells respond to calcium readdition. However, this defect is likely specific to apical ring disassembly and junction assembly, because no significant differences were observed in the overall spreading rate of ZO-1-depleted cells when plated onto collagen-coated coverglasses, compared with the spreading rate of control cells (our unpublished data).

Gene Silencing of Occludin, Cingulin, or ZO-2 Has No Effect on Tight Junction Assembly

We were concerned that the phenotype induced by ZO-1 knockdown might be a nonspecific or general effect induced by the loss of any junction protein. Therefore, we tested the response to silencing of occludin expression. Occludin has been shown to be dispensable for tight junction formation in mice, although it is essential for gastric epithelial differentiation (Saitou et al., 1998, 2000; Schulzke et al., 2005). Silencing by RNAi in MDCK cells has been shown previously to have little effect on tight junction integrity (Yu et al., 2005).

We designed pSUPER vectors targeted against two distinct sequences within the canine occludin ORF. Each vector knocked down the level of the endogenous protein by >90%, without effecting the levels of ZO-1, E-cadherin, or β-catenin (our unpublished data). Immunofluorescence showed a clear reduction of occludin staining at the cell boundaries, but there was no apparent defect in ZO-1 localization, either in normal medium or 60 min after a calcium switch (our unpublished data). This result confirms previous data (Yu et al., 2005) that occludin expression is not required for the normal assembly of tight junctions in MDCK cells. Moreover, when the transepithelial resistance was measured after a calcium switch, the control and occludin-knockdown cells generated a similar profile, confirming that tight junctions lacking occludin are functionally intact, as has been concluded from studies in knockout mice (Saitou et al., 2000; Schulzke et al., 2005). Together, these data support the conclusion that the phenotype of cells lacking ZO-1 reflects a specific requirement for ZO-1 in junction assembly. Additionally, they suggest that the reported interaction of ZO-1 with occludin is not important for ZO-1 localization or for junction assembly.

We next tested the effects of silencing expression of two other known ZO-1 binding partners, ZO-2 and cingulin. Efficient silencing of ZO-2 expression had no discernible phenotype and did not potentiate the inhibition of junction assembly caused by knockdown of ZO-1 (Figure 5, A and C). Cingulin does not localize correctly in murine epithelial cells that lack ZO-1 (Umeda et al., 2004), so it seemed reasonable that this protein might play a role in junction assembly. However, disruption of the cingulin gene in murine embryoid bodies did not cause a loss of tight junctions (Guillemot et al., 2004), and, consistent with these data, knockdown of cingulin in MDCK cells did not alter ZO-1 localization nor did it inhibit junction reassembly after a calcium switch (Figure 5, B and C). Knockout of the cingulin gene did cause changes in the levels of gene expression for several junction proteins (Guillemot et al., 2004). The occludin protein in particular was dramatically increased in cingulin -/- cells. We therefore blotted for a number of junction proteins in cells depleted of cingulin, occludin, ZO-1, or ZO-2 (Figure 5D) but found no significant changes in level, compared with the control MDCK cells. Moreover, we observed no effects of knocking down any of the proteins on the paracellular diffusion of [3H]inulin (Figure 5E). We conclude that wild-type levels of cingulin, occludin, or ZO-2 are not required for the normal formation of tight junctions in MDCK cell monolayers.

Figure 5.

Tight junction assembly is not inhibited by silencing of ZO-2 or cingulin expression. (A) Cells were transfected with shRNAs targeted against canine ZO-1 and/or ZO-2, and after 3 d, lysates were blotted for ZO-1, ZO-2, and β-catenin (as a loading control). (B) Cells were transfected with shRNAs targeted against canine cingulin and after 3 d, lysates were blotted for cingulin and occludin (as a loading control). (C) Cells transfected as described in A and B were subjected to a calcium switch and then fixed 3 h after calcium readdition and stained for occludin. Images were processed as described in Figure 2. (D) Cells were transfected with a control shRNA or with shRNAs targeting ZO-1, ZO-2, occludin, or cingulin. For ZO-1, occludin, and cingulin, a mix of two shRNAs against each target was used. After 3 d, lysates were collected, and equal amounts of protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. (E) Cells were transfected as described in D and then grown on Transwell filters to form confluent monolayers. [3H]Inulin (0.5 μCi) was added to the top well, and the ratio of 3H in the top/bottom wells was measured after 30 min. The experiment was performed in triplicate and values are ± 1 SD.

Rescue of Tight Junction Assembly by Mutants and Fragments of ZO-1

ZO-1 is a multidomain protein, but the requirement for individual domains in junction assembly is not known. To address this issue, we used gene rescue with various mutants of the murine ZO-1. Initially, we tested several deletion mutants (Figure 6, A and B). We removed the C-terminal region of ZO-1 that contains the ZU-5 domain, and, as shown in Figure 7B, when YFP-ZO-1(1-1523) was cotransfected into cells with the pSUPER-ZO-1 constructs, it was able to rescue tight junction reassembly after calcium switch to an extent similar to that of the full-length protein. Surprisingly, however, it did not localize efficiently to the cell boundaries. This result suggests that localization might not be essential for the function of ZO-1 in forming tight junctions. In contrast, the isolated C-terminal region, HA3-ZO-1(893-1666), which contains both the actin binding domain and the ZU5 domain, did not rescue junction assembly (Figure 6, A and C). The fragments were expressed at similar levels to the full-length ZO-1 (Figure 6D).

Figure 7.

Rescue of junction assembly by the isolated SH3 domain of ZO-1. (A) Cells were transfected with shRNAs against ZO-1 together with pKGFP or a PKGFP-mZO-1 containing either the mutated SH3 domain or a revertant in which the mutation in the SH3 domain had been repaired. (B) Cells were transfected with either an empty pSUPER vector or with shRNAs against ZO-1, together with YFP or YFP fused to the isolated, wild-type SH3 domain of ZO-1, the inactive mutant SH3 domain, or to the SH3 domain of the p120 RasGAP. Images were analyzed as described in Figure 6. Mean pixel values are shown for each treatment ± 1 SD, and asterisks show values that are significantly different either from the control or from the knock-down plus YFP (p < 0.01).

The data were analyzed quantitatively, using the mean line intensity as a measure of junction intactness. For each condition, fields of cells were analyzed from multiple experiments, and the mean and SD were calculated. Differences were assessed by a t test. A histogram of these values is shown in Figure 6E, for occludin staining 3 h postcalcium switch. Gene silencing of ZO-1 reduces the line intensity by ∼90% and full-length YFP-ZO-1 restores the intensity to the control value. Transfection of the C terminus raises the value only to ∼30% of control, whereas the N-terminal fragments can rescue junction formation by 80-100% of the control value.

To determine the role of distinct domains in junction assembly, we constructed several further mutants. A ΔGUK mutant, in which most of the GUK domain has been deleted, was able to localize quite well to cell boundaries, but it did show a partial assembly defect (Figure 6, D and F). A point mutant in the N-terminal PDZ domain (PDZ1) was constructed that replaces the positively charged residue in the ligand binding site (Arg) with a negatively charged residue (Glu). The Arg normally forms a salt-bridge to the C-terminal carboxyl group on peptides that bind to PDZ domains (Doyle et al., 1996). A Glu is therefore expected to substantially reduce the affinity of the PDZ1 domain for its binding partners. This mutant was recruited to the cell boundaries even more efficiently than the wild-type YFP-ZO-1 and was able to rescue junction formation (Figure 6, D-F), indicating that the PDZ1 domain is not essential for ZO-1 function.

We next mutated the SH3 domain, converting the conserved Trp residue to Gly and the adjacent Leu to Ala. These residues are within the binding pocket of SH3 domains and are essential for interaction with PxxP ligands (Pawson and Gish, 1992). This mutant form of YFP-ZO-1 was only poorly localized to cell boundaries, and it did not efficiently rescue tight junction assembly, giving a mean occludin intensity value ∼55% compared with control cells (Figure 6, D-F; p = 0.01). Importantly, each of the mutants tested was of the predicted size and showed no evidence of proteolytic degradation (Figure 6C). However, the requirement for a functional SH3 domain was unexpected, because no known binding partners for this domain have been implicated in junction assembly. We were therefore concerned that we had introduced a spurious mutation elsewhere in the ZO-1 open reading frame. To test this possibility, we replaced the mutant SH3 domain with the wild-type version and retested the YFP-ZO-1. This revertant was capable of rescuing junction assembly with ∼90% efficiency (Figures 6E and 7A). Therefore, we are confident that the observed requirement for an intact SH3 domain is correct.

Finally, we wondered whether the isolated SH3 domain of ZO-1 might be sufficient to rescue junction assembly in cells depleted of endogenous ZO-1. To this end, we expressed a fusion of the SH3 domain and YFP. Surprisingly, junction assembly seemed to be relatively normal in knockdown cells that expressed this fusion protein (Figure 7B), even though this construct was diffuse within the cytoplasm (our unpublished data). The mutated SH3 domain, however, did not efficiently rescue junction assembly. In addition, as a control for specificity, we tested an SH3 domain from the p120 RasGAP. This domain did not rescue junction assembly (Figure 7B). Together, these data suggest that the SH3 domain of ZO-1 can regulate the formation of tight junctions even when it does not localize correctly to the junctions, perhaps by sequestering an assembly inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

The MAGUK proteins, including ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, have long been assumed to be essential components of the tight junctions in epithelial cells and to be linked to tumor progression. For example, the ectopic expression of various fragments of these proteins can interfere with tight junction assembly and function; ZO-2 expression is reduced in many breast and pancreatic adenocarcinomas (Chlenski et al., 2000), and it is a target for the adenovirus type 9 E4 oncogenic protein (Glaunsinger et al., 2001); and ZO-1 expression is also lost in some breast tumors (Hoover et al., 1998). Nonetheless, the changes in expression level might be an effect of neoplastic transformation rather than a cause, and overexpressed proteins can mistarget and sequester binding partners away from their normal location in the cell, leading to defects unrelated to their normal function. Suppression of expression by RNAi can potentially avoid these concerns, and, when coupled with gene rescue and a quantitative assay, it can provide valuable information on structural requirements for function. Off-target effects and incomplete knockdown can complicate the interpretation of RNAi data (Jackson et al., 2003). In ZO-1, we have eliminated the concern about off-target effects by showing that expression of a human YFP-ZO-1 can reverse the phenotype caused by depletion of the endogenous protein. Moreover, ZO-1 RNAi phenocopies a homozygous disruption of the ZO-1 gene in Eph4 cells, suggesting that the knockdown is effectively eliminating ZO-1 function (Umeda et al., 2004).

The defect caused by loss of ZO-1 is kinetic—normal tight junctions do form in the absence of ZO-1, but the initial steps in assembly are unusually slow. Once initialization is complete, however, assembly proceeds at a similar rate to that seen in control cells, although the transepithelial resistance never peaks in ZO-1-depleted cells. Presumably, therefore, the event that triggers this overshoot in resistance occurs during the first 3 h. By time-lapse imaging, tight junction components were observed to be partially retained in an apical ring and also to be present in bright spots, presumably vesicles, which were corralled within this ring structure. The ring is reminiscent of a similar structure observed in isolated intestinal epithelial cells that ectopically express active LKB1. These cells possess an intrinsic apical/basal polarity, even though they are not in contact with neighboring cells (Baas et al., 2004). The same polarity seems to exist in the MDCK cells subjected to calcium withdrawal. This interpretation is supported by recent evidence that the apical marker gp135/podocalyxin is also confined to a “pre-apical” domain in MDCK cells plated onto coverslips (Meder et al., 2005). The apical ring rapidly disintegrates upon cell-cell contact and reassembles at these contacts, as some of the fragments form “primordial spot junctions,” which spread into a tight junction belt that encircles each cell (Figure 8) (Ando-Akatsuka et al., 1999).

Interestingly, in the cells lacking ZO-1, the lamellipodia-like extensions induced by calcium addition were observed to be smaller than in control cells, and the apical ring remained intact and spread slowly to the cell periphery (Figure 8). We speculate that this behavior indicates a possible defect in actin dynamics. However, the mechanisms by which ZO-1 might regulate actin dynamics remain unclear. YFP-ZO-1 is also present in the apical ring and undergoes the same morphological transitions as were observed for YFP-occludin, so it is possible that the ZO-1 directly modulates actin in this ring or acts indirectly to do so through one of its binding partners. However, depletion of known partners for ZO-1, such as occludin, cingulin, and ZO-2, had no detectable effects on tight junction assembly.

The key regions of ZO-1 involved in junction assembly were, unexpectedly, the SH3 and (to a marginal extent) the GUK domain. These two domains are thought to interact and may regulate one another (Wu et al., 2000). What is their function? The GUK domain has been reported to bind occludin (Fanning et al., 1998; Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003), but occludin is not required for junction assembly. The SH3 region of ZO-1 can bind G protein α subunits, but these actually interact with an acidic region C-terminal to the domain, and the interaction is unlikely to be perturbed by the point mutations we introduced into the ligand binding site (Gonzalez-Mariscal et al., 2003). Finally, the SH3 domain can bind ZONAB, but this transcription factor seems to regulate cell proliferation rather than junction assembly (Balda et al., 2003). Overexpression of ZONAB did not alter the dynamics of junction assembly in our hands (our unpublished data). Therefore, we speculate that other binding partners exist, and the key to understanding ZO-1 function will be to determine their identity. The observation that the isolated SH3 domain of ZO-1 can rescue assembly even though it does not localize correctly suggests that the binding partner for the SH3 domain might not be a junction component but can interfere with assembly unless it is sequestered by ZO-1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dirk Hunt (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) for the canine ZO-1 cDNA, Tom Parsons for the cortactin antibody, and Anne Spang (Friedrich Miescher Laboratory, Tübingen, Germany) and members of the Macara laboratory for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by Grants GM-070902 and CA-040042 from the National Institutes of Health Department of Health and Human Services.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0650) on January 25, 2006.

Abbreviations used: GUK, guanylate kinase-like; PDZ, PSD-95, Discs large, ZO-1; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Ando-Akatsuka, Y., Yonemura, S., Itoh, M., Furuse, M., and Tsukita, S. (1999). Differential behavior of E-cadherin and occludin in their colocalization with ZO-1 during the establishment of epithelial cell polarity. J. Cell. Physiol. 179, 115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas, A. F., Kuipers, J., van der Wel, N. N., Batlle, E., Koerten, H. K., Peters, P. J., and Clevers, H. C. (2004). Complete polarization of single intestinal epithelial cells upon activation of LKB1 by STRAD. Cell 116, 457-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda, M. S., and Anderson, J. M. (1993). Two classes of tight junctions are revealed by ZO-1 isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. 264, C918-C924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda, M. S., Anderson, J. M., and Matter, K. (1996). The SH3 domain of the tight junction protein ZO-1 binds to a serine protein kinase that phosphorylates a region C-terminal to this domain. FEBS Lett. 399, 326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda, M. S., Garrett, M. D., and Matter, K. (2003). The ZO-1-associated Y-box factor ZONAB regulates epithelial cell proliferation and cell density. J. Cell Biol. 160, 423-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda, M. S., and Matter, K. (2000). The tight junction protein ZO-1 and an interacting transcription factor regulate ErbB-2 expression. EMBO J. 19, 2024-2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp, T. R., Bernards, R., and Agami, R. (2002). A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296, 550-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., and Macara, I. G. (2005). Par-3 controls tight junction assembly through the Rac exchange factor Tiam1. Nat. Cell Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chlenski, A., Ketels, K. V., Korovaitseva, G. I., Talamonti, M. S., Oyasu, R., and Scarpelli, D. G. (2000). Organization and expression of the human zo-2 gene (tjp-2) in normal and neoplastic tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1493, 319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordenonsi, M., D'Atri, F., Hammar, E., Parry, D. A., Kendrick-Jones, J., Shore, D., and Citi, S. (1999). Cingulin contains globular and coiled-coil domains and interacts with ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, and myosin. J. Cell Biol. 147, 1569-1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Atri, F., and Citi, S. (2002). Molecular complexity of vertebrate tight junctions (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 19, 103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, D. A., Lee, A., Lewis, J., Kim, E., Sheng, M., and Mackinnon, R. (1996). Crystal structures of a complexed and peptide-free membrane protein-binding domain-molecular basis of peptide recognition by PDZ. Cell 85, 1067-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q., and Macara, I. G. (2004). Mammalian Pins is a conformational switch that links NuMA to heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell 119, 503-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnet, K., Schulz, C. U., Meyer Zu Brickwedde, M. K., Pendl, G. G., and Vestweber, D. (2000). Junctional adhesion molecule interacts with the PDZ domain-containing proteins AF-6 and ZO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27979-27988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning, A. S., Jameson, B. J., Jesaitis, L. A., and Anderson, J. M. (1998). The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29745-29753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke, L., Dakoji, S., and Bredt, D. S. (2005). Membrane-associated guanylate kinases regulate adhesion and plasticity at cell junctions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 219-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse, M., Itoh, M., Hirase, T., Nagafuchi, A., Yonemura, S., and Tsukita, S. (1994). Direct association of occludin with ZO-1 and its possible involvement in the localization of occludin at tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1617-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, M. C., and Perrimon, N. (2003). Apicobasal polarization: epithelial form and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaunsinger, B. A., Weiss, R. S., Lee, S. S., and Javier, R. (2001). Link of the unique oncogenic properties of adenovirus type 9 E4-ORF1 to a select interaction with the candidate tumor suppressor protein ZO-2. EMBO J. 20, 5578-5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mariscal, L., Betanzos, A., Nava, P., and Jaramillo, B. E. (2003). Tight junction proteins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 81, 1-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot, L., Hammar, E., Kaister, C., Ritz, J., Caille, D., Jond, L., Bauer, C., Meda, P., and Citi, S. (2004). Disruption of the cingulin gene does not prevent tight junction formation but alters gene expression. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5245-5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, K. B., Liao, S. Y., and Bryant, P. J. (1998). Loss of the tight junction MAGUK ZO-1 in breast cancer: relationship to glandular differentiation and loss of heterozygosity. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1767-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, M., Furuse, M., Morita, K., Kubota, K., Saitou, M., and Tsukita, S. (1999). Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J. Cell Biol. 147, 1351-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A. I., McCall, I. C., Parkos, C. A., and Nusrat, A. (2004a). Role for actin filament turnover and a myosin II motor in cytoskeleton-driven disassembly of the epithelial apical junctional complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2639-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A. I., Nusrat, A., and Parkos, C. A. (2004b). Endocytosis of epithelial apical junctional proteins by a clathrin-mediated pathway into a unique storage compartment. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 176-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, A. L., Bartz, S. R., Schelter, J., Kobayashi, S. V., Burchard, J., Mao, M., Li, B., Cavet, G., and Linsley, P. S. (2003). Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 635-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsube, T., Takahisa, M., Ueda, R., Hashimoto, N., Kobayashi, M., and Togashi, S. (1998). Cortactin associates with the cell-cell junction protein ZO-1 in both Drosophila and mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29672-29677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knust, E., and Bossinger, O. (2002). Composition and formation of intercellular junctions in epithelial cells. Science 298, 1955-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Olson, C., Lu, S., Kamasawa, N., Yasumura, T., Rash, J. E., and Nagy, J. I. (2004). Neuronal connexin36 association with zonula occludens-1 protein (ZO-1) in mouse brain and interaction with the first PDZ domain of ZO-1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 2132-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara, I. G. (2004). Parsing the polarity code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 220-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter, K., and Balda, M. S. (2003). Functional analysis of tight junctions. Methods 30, 228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meder, D., Shevchenko, A., Simons, K., and Fullekrug, J. (2005). Gp135/podocalyxin and NHERF-2 participate in the formation of a preapical domain during polarization of MDCK cells. J. Cell Biol. 168, 303-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. N., Schwesinger, C., and Denker, B. M. (2002). Zonula occludens-1 is a scaffolding protein for signaling molecules. Galpha(12) directly binds to the Src homology 3 domain and regulates paracellular permeability in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24855-24858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, W. J. (2003). Adaptation of core mechanisms to generate cell polarity. Nature 422, 766-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, S. (2001). Intercellular junctions and cellular polarity: the PAR-aPKC complex, a conserved core cassette playing fundamental roles in cell polarity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 641-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, T., and Gish, G. D. (1992). SH2 and SH3 domains: from structure to function. Cell 71, 359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, M., Fujimoto, K., Doi, Y., Itoh, M., Fujimoto, T., Furuse, M., Takano, H., Noda, T., and Tsukita, S. (1998). Occludin-deficient embryonic stem cells can differentiate into polarized epithelial cells bearing tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 141, 397-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, M., Furuse, M., Sasaki, H., Schulzke, J. D., Fromm, M., Takano, H., Noda, T., and Tsukita, S. (2000). Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4131-4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke, J. D., Gitter, A. H., Mankertz, J., Spiegel, S., Seidler, U., Amasheh, S., Saitou, M., Tsukita, S., and Fromm, M. (2005). Epithelial transport and barrier function in occludin-deficient mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1669, 34-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K., Straight, S., and Margolis, B. (2005). PATJ regulates tight junction formation and polarity in mammalian epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 168, 705-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita, S., and Furuse, M. (2002). Claudin-based barrier in simple and stratified cellular sheets. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 531-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda, K., Matsui, T., Nakayama, M., Furuse, K., Sasaki, H., Furuse, M., and Tsukita, S. (2004). Establishment and characterization of cultured epithelial cells lacking expression of ZO-1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44785-44794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmann, R., and Nelson, W. J. (2005). Fractionation of the epithelial apical junctional complex: reassessment of protein distributions in different substructures. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 701-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott, E., Balda, M. S., Heintzelman, M., Jameson, B., and Anderson, J. M. (1992). Localization and differential expression of two isoforms of the tight junction protein ZO-1. Am. J. Physiol. 262, C1119-C1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H., Reissner, C., Kuhlendahl, S., Coblentz, B., Reuver, S., Kindler, S., Gundelfinger, E. D., and Garner, C. C. (2000). Intramolecular interactions regulate SAP97 binding to GKAP. EMBO J. 19, 5740-5751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A. S., McCarthy, K. M., Francis, S. A., McCormack, J. M., Lai, J., Rogers, R. A., Lynch, R. D., and Schneeberger, E. E. (2005). Knockdown of occludin expression leads to diverse phenotypic alterations in epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 288, C1231-C1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.