Abstract

The ciaR-ciaH system is one of 13 two-component signal-transducing systems of the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mutations in the histidine protein kinase CiaH confer increased resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics and interfere with the development of genetic competence. In order to identify the genes controlled by the cia system, the cia regulon, DNA fragments targeted by the response regulator CiaR were isolated from restricted chromosomal DNA using the solid-phase DNA binding assay and analyzed by hybridization to an oligonucleotide microarray representing the S. pneumoniae genome. A set of 18 chromosomal regions containing 26 CiaR target sites were detected and proposed to represent the minimal cia regulon. The putative CiaR target loci included genes important for the synthesis and modification of cell wall polymers, peptide pheromone and bacteriocin production, and the htrA-spo0J region. In addition, the transcription profile of cia loss-of-function mutants and those with an apparent activated cia system representing the off and on states of the regulatory system were analyzed. The transcript analysis confirmed the cia-dependent expression of seven putative target loci and revealed three additional cia-regulated loci. Five putative target regions were silent under all conditions, and for the remaining three regions, no cia-dependent expression could be detected. Furthermore, the competence regulon, including the comCDE operon required for induction of competence, was completely repressed by the cia system.

Bacterial two-component signal-transducing systems (TCSTS) mediate adaptive responses to environmental signals. They typically consist of two modular proteins: a histidine protein kinase that acts as a sensor for external stimuli and a cytoplasmic response regulator that translates the signal into a cellular response by changing the expression profiles of targeted genes (40, 51). The TCSTS ciaRH was the first of 13 such systems identified in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae (19). Two membrane-spanning regions in CiaH are proposed to separate the N-terminal external sensor domain from the cytoplasmic kinase domain. The response regulator CiaR contains a typical DNA binding domain characteristic of this subclass of regulators (35). The two genes are arranged in an operon with a 8-bp overlap (19).

Mutations in the histidine protein kinase ciaH conferred increased resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, revealing a novel pathway for resistance development in this organism and suggesting that ciaR may control genes that are involved in the biochemistry of the bacterial cell wall (19, 60). Other phenotypes in cia mutants have since been described, such as growth defects associated with the tendency for early lysis (17, 22, 27; T. Mascher, M. Merai, and D. Zähner, unpublished results) and attenuation of virulence (53), again indicating that the cia system plays an important role in the maintenance of the overall integrity of the cell wall.

Curiously, ciaH mutants were affected in the development of genetic competence as well (19, 20), an effect which has since been confirmed in several recent publications (14, 34, 58). The comCDE system, which is responsible for the induction of genetic competence, is a complex regulatory network: the CSP peptide, the processed secreted product of comC, is recognized by the histidine protein kinase ComD, and the response regulator ComE is responsible for autoinduction of the comCDE operon and other early genes, among which are the transcriptional activators ComX1 and ComX2, which in turn induce the late competence genes (43). Using crude preparations of so-called competence factor, competence could not be induced in noncompetent ciaH mutants; however, after the identification of the competence factor as a small unmodified peptide, CSP (24), chemically synthesized CSP could be used in higher concentrations and complemented this defect in all ciaH mutants analyzed (60). This suggested that either the export, the stability, or the sensing of CSP is affected in cia mutants.

What are the genes controlled by the ciaRH system, and what is the link between the two TCSTS, ciaRH and comDE? It has been suggested that the cia system is related to the biosynthesis of cell wall components at steps prior to biosynthetic functions of penicillin binding proteins functioning during the final assembly of the peptidoglycan (22). However, neither the molecular nature of the signal sensed by the CiaH kinase nor cia-regulated genes are known. Genes directly controlled by the response regulator CiaR should be located in the vicinity of CiaR binding sites. In order to identify such CiaR target regions, we have used a DNA binding assay based on a method established for the Escherichia coli DNA binding protein DnaA (48). In the solid-phase DNA binding (SPDB) assay, an overexpressed, biotinylated fusion derivative of a DNA binding protein is purified via its interaction with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, and after incubation with DNA fragments, those that show specific interaction with the protein can be isolated and analyzed further. We have modified this procedure for the response regulator CiaR and used an oligonucleotide microarray for identifying the set of DNA fragments obtained from restricted chromosomal DNA of S. pneumoniae.

The results are in agreement with the hypothesis that several cia-regulated genes are involved in the biochemical makeup of the cell envelope, including modifications of peptidoglycan, surface-exposed proteins, and a variety of transport systems. Transcript analysis of cia mutants in comparison with wild-type cells was used to confirm the cia-dependent transcription of such loci. In addition to cia-dependent expression of some of the putative target loci, repression of the entire competence regulon by the cia system could be documented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

S. pneumoniae strains were routinely grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Difco) or in the semidefined C medium (26) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (Difco) at 37°C without aeration. S. pneumoniae R6 is a transformable, unencapsulated laboratory strain derived from the type 2 strain D39 (50). The genomic sequence of the encapsulated type 4 strain KNR.7/87 (1, 52) served as the basis for the oligonucleotide microarray used for this study. R6ciaHC306 is a transformant obtained with the ciaH gene of the mutant C306 which carries the mutation T230>P (19). E. coli WM1704 (46) is a pMC9-cured derivative of strain Y1089 (57). E. coli was routinely grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C; exceptions are stated in the text. pBEX5BA (46) and its derivatives were selected in E. coli with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml.

Construction of lacZ reporter strains and β-galactosidase assay.

To monitor lacZ expression, a β-galactosidase-negative derivative of the S. pneumoniae R6 strain (R6bga::erm) was used (59). The plasmid pXF520 carrying part of the comC leader peptide and upstream sequences, with a fusion to the lacZ reporter gene at the 15th codon of the comC gene, has been described (41). R6 Cmr transformants were isolated, and a blue colony was used for the introduction of cia mutations. Insertion-duplication mutants in ciaR produced dark-blue colonies, whereas introduction of the ciaHC306 allele resulted in white colonies; no mixed populations were observed for the cia mutants as has been described for strains grown under competence-preventing conditions (58). Chromosomal fusion of the lacZ′ gene under the control of the lic and dlt promoter regions was performed using the lacZ reporter plasmid pEVP3 (11). The dlt promoter region was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide pair 5′-AAAGTGTAGATCTTCAGGAAACAGTAGAGG and 5′-GCGGCATTCTAGACAGGATAGCTAGGCTG, covering the region from position −704 to +62 in respect to the A1TG start codon; the lic promoter region was obtained with the primers 5′-CCAATGCATCGGTCCAAGACACGCGCG and 5′-CGGGATCCGCGTGTGCCAGTTCCACC, covering the region −447 to +50. The fragments were transcriptionally fused to the lacZ′ gene of pEVP3, and the resulting plasmids were integrated into the chromosome upstream of the operons by homologous recombination, resulting in strains R6bga::erm,dltA::pEVP3 and R6bga::erm, licA::pEVP3. Correct integration was confirmed by PCR using pairs of oligonucleotides priming within pEVP3 and in the respective promoter region. The β-galactosidase assay was based on the classical procedure (36) and was performed as described previously (41).

Construction of ciaR loss-of-function mutants.

The spectinomycin resistance gene aad9 from pDL278 (29) was used for disruption of the cia genes. The ciaR gene was cloned into the vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). The aad9 gene was amplified with the oligonucleotide pair 5′-gctagcATCGATTTTCGTTCGTGAATAC and 5′-gctagcCCAATTAGAATGAATATTCCC containing flanking NheI sites (lowercase). The gene was then recovered by NheI digestion and ligated into the single AvrII site of pCR2.1 carrying ciaR. The resulting construct, ciaR::aad9, was amplified using the oligonucleotide pair 5′-GCTTTGTTATCCTTCCTGCTC and 5′-cccaagcttGAGAAGGGCCTGAATCCGCAT (the lowercase letters indicate the HindIII site) and transformed into R6 using 80 mg of spectinomycin/ml for selection. Transformation of S. pneumoniae strains was performed essentially according to published procedures, with 30 min of incubation in the presence of DNA at 30°C followed by a 2-h phenotypic-expression period at 37°C (19). All constructs were confirmed by PCR using pairs of oligonucleotide primers flanking the insertion. The resulting mutant was named R6-R1 (ciaR::aad9).

Construction and isolation of bCiaR.

The vector pBEX5BA (46) was used for the construction of a biotinylated derivative of CiaR (bCiaR). The vector contains the gene encoding the 12.5-kDa subunit of the transcarboxylase complex from Propionibacterium shermanii directly upstream from the multiple cloning site. This subunit harbors a target sequence for the E. coli enzyme biotin-apoprotein ligase, which transfers a biotin residue to this peptide (38). The complete ciaR gene of S. pneumoniae was amplified by PCR (nucleotides 219 to 889 according to GenBank accession number X77249) using the oligonucleotide pair 5′-cgggatccATAAAAATCTTATTGGTTGAGG and 5′-cccaagcttACTGAACATCTTTTAAAAGAT (terminal restriction sites [lowercase] were included). The fragment obtained was translationally fused with its 5′ end to the 3′ end of the gene coding for the 12.5-kDa subunit of the transcarboxylase complex of P. shermanii, leading to the fusion gene bciaR. The resulting plasmid, pDZ9, was transformed in E. coli WM1704. The DNA sequence of bciaR was confirmed by DNA sequencing. E. coli WM1704(pDZ9) was grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 2 μM biotin in the presence of 100 μg of ampicillin/ml at 28°C to prevent the formation of inclusion bodies. Expression of bCiaR was induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 100 μM final concentration) at an optical density at 560 nm of 0.7 for 2.5 h. The expression of the CiaR derivative was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomassie staining of the proteins and on Western blots using an anti-CiaR specific rabbit antiserum; biotinylation of bCiaR was confirmed by near-Western blotting with a streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate.

Crude preparation of bCiaR.

After induction with IPTG for 2.5 h as described above, E. coli WM1704(pDZ9) cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 1/20 of the culture volume in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3)-10 mM MgCl2-100 mM KCl; 500-μl aliquots of this suspension were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Immediately before use, the aliquots were thawed on ice and the cells were disintegrated on ice by sonication (three intervals of 1 min each). Intact cells and cell envelope fragments were removed by centrifugation (Heraeus Biofuge 28RS; 24,000 rpm [∼40,000 × g]; 15 min; 4°C), and the supernatant containing bCiaR was used directly in the SPDB assay.

DNA sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequencing was performed using the ABI Prism dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin Elmer-ABI).

Preparation of chromosomal restriction fragments.

Chromosomal DNA of S. pneumoniae KNR.7/87 was prepared as previously described (23) and digested with either HindIII, RsaI, or Sau3A1 in a 200-μl final volume. The enzymes were heat inactivated, and salt was removed by dialysis on a membrane filter (type VS; 0.025-μm pore size; Millipore, Eschborn, Germany).

SPDB assay.

The SPDB assay was performed according to published procedures with modifications (48). Strepavidin-coated magnetic beads (20 μl) (Dynabeads M-280; Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) were washed four times with 40 μl of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3)-100 mM KCl (BB buffer) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor mix (PIM) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) as described by the manufacturer and finally resuspended in 40 μl of BB-PIM. The beads were mixed with 80 μl of crude extract of WM1704(pDZ9) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. No phosphorylation reaction was performed for bCiaR. The protein-coated beads were vigorously washed three times with 40 μl of BB-PIM supplemented with 0.4% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) and five times with 40 μl of BB. Finally, the beads were resuspended in 80 μl of BB, mixed with 20 μl of restricted chromosomal DNA of S. pneumoniae, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Nonspecifically bound DNA was removed by washing the beads with 40 μl of BB (three times). DNA fragments specifically interacting with bCiaR were eluted after incubation of the coated beads with 1.3 M NaCl (40 μl) for 5 min. The eluted DNA was precipitated with ethanol-glycogen and collected by centrifugation before further use. The specificity of binding was verified using 10 ng of the PCR-amplified putative target fragment to be tested together with a mixture of unrelated DNA fragments (125 ng of competitor DNA [DNA molecular weight marker X; Roche]) in the SPDB assay as described above. The eluted DNA fragments were separated on 1% agarose gels and visualized on a Fluorimager (Molecular Dynamics) after being stained with SYBRgreen (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oreg.).

DNA fragmentation and labeling.

The detection limit for DNA fragments used for hybridization on the microarray was tested for five probe sets and estimated to be ∼5 ng per kb. SPDB-derived DNA fragments from 5 to 7 assays (RsaI- and Sau3A-restricted chromosomal DNA) or 20 assays (HindIII-restricted DNA) were combined, and the amount finally used was estimated to represent between 10 and 20 ng per kb of DNA fragmen per assay. The pooled DNA fragments were diluted in 200 μl of water and sonicated on ice three times for 1 min each time, resulting in fragments of an average size of 300 to 500 bp. Using a relatively small amount of hybridizing DNA of low complexity required adjustment of the fragmentation conditions used previously (21). After ethanol precipitation, the DNA was resuspended in 89 μl of water and further fragmented by partial DNase treatment for 10 s at 37°C using 0.005 U of DNase I in RQ1 buffer (Promega) in a final volume of 100 μl. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml), and incubation continued for another 3 min at 37°C. The average size of the resulting fragments decreased during this period to between 50 and 100 bp. The DNA was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 85 μl of H2O, and quantified spectrophotometrically. DNA labeling was performed with biotin-labeled ddATP incorporated at the 3′ end of the fragmented DNA using Terminal-deoxy-Transferase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) as described previously (21).

RNA extraction and cDNA labeling.

The preparation of RNA was done as previously described (13). In brief, 30-ml cultures grown in the absence of antibiotics were harvested in late exponential growth phase by centrifugation, and the cell pellet was frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Each experiment was done in duplicate with two different cultures with all preparation steps performed independently. RNA was isolated using the hot-phenol method (33) and finally purified through Qiagen RNeasy columns as instructed by the manufacturer in order to remove small RNA molecules. The hybridization target was synthesized by an optimized reverse-transcription reaction from total RNA in the presence of random hexanucleotides and biotin-labeled dATP during overnight incubation at 37°C in a 100-μl volume according to the published procedure (13).

Microarray design.

The oligonucleotide microarray used in this study represents the two genomes of S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. It was custom designed by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, Calif.), and details have been described previously (13, 21). In summary, the S. pneumoniae genome of strain KNR.7/87, represented by a total of 2,291 probe sets covering 1,968 predicted open reading frames and 323 intergenic regions larger than 200 bp, was considered in the final analysis. The oligonucleotide probe selection (25-mers) and array fabrication were performed by Affymetrix according to published procedures (31, 56). In general, each gene represented on the ROEZ06a microarray has 25 probe pairs, with at least 20 probe pairs for very short genes. A probe pair consists of a perfect-match probe and a mismatch probe that is identical except for a single base change in the central position. The position of the oligonucleotide on each gene is determined by sequence uniqueness criteria based on empirical rules for the selection of oligonucleotides likely to hybridize with high specificity and sensitivity (31).

Hybridization and staining procedures.

Hybridization and staining of DNA fragments were carried out essentially as described previously (13, 21). The solutions contained 100 mM MES (N-morpholinoethane-sulfonic acid), 1 M Na+, 20 mM EDTA, and 0.01% Tween 20. In addition, unlabeled fragmented yeast RNA (3 mg/ml; Roche Molecular Biochemicals), acetylated bovine serum albumin (1.5 mg/ml), and TOP Block (20 mg/ml; Juro, Lucerne, Switzerland) were used. In brief, the microarrays were washed and prehybridized for 10 min at 40°C. Biotin-labeled DNA fragments were hybridized overnight at 40°C on a rotisserie. After removal of the hybridization mixture, the arrays were rinsed and washed with 6× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7])-0.01% Tween 20 (40°C for 20 min). A stringent wash was then performed with 0.5× SSPE-0.01% Tween 20 for 15 min at 45°C. The hybridized DNA was labeled with streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate (3 μg/ml; Molecular Probes) and acetylated bovine serum albumin (2 mg/ml) in 6× SSPE-0.01% Tween 20 for 10 min at 40°C. Further signal amplification was also performed with a biotinylated anti-streptavidin antibody and subsequent staining with streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate. A final washing step was performed in 6× SSPE-0.01% Tween 20 for 10 min at 40°C prior to scanning. All hybridizations with the microarray were performed at least in duplicate.

Data processing.

The microarrays were scanned at 570 nm (3-μm resolution) with a gene chip scanner (Affymetrix) and analyzed as previously described (31). The signal intensity for each gene is calculated as the average intensity difference, represented by the following expression: (PM MM)/number of probe pairs, where PM and MM denote perfect-match and mismatch probes. Due to the background caused by DNA fragments present in the SPDB assay that are not specifically associated with bCiaR, the minimum average intensity difference for each gene was set to 100, which corresponds to the noise; for the experiments using cDNA, the minimum average intensity difference was set to 20. Probe sets with an average intensity difference of at least fivefold above background were extracted and assembled according to the available genome sequence (http://www.tigr.org).

Computational analysis.

Protein homology and genetic analyses of open reading frames were performed using the ORFfinder and BLAST algorithms (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers are as follows: S. pneumoniae genome KNR.7/87 (TIGR4), AE005672; S. pneumoniae R6 genome, AE007317 (25, 52).

RESULTS

Isolation of CiaR DNA target regions.

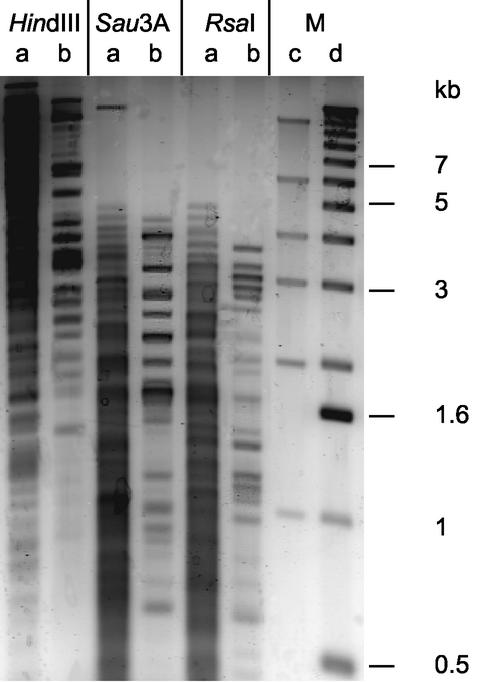

In the SPDB assay for isolation of CiaR DNA target fragments, the derivative bCiaR was expressed in E. coli, where the CiaR DNA binding domain remains free at the C terminus and the N terminus has been fused to a peptide that becomes biotinylated in E. coli (see Materials and Methods for details). The purification of bCiaR was achieved in one step, incubating a crude E. coli cell lysate containing the overproduced, biotinylated bCiaR with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. The carefully washed protein-loaded beads were then incubated with restricted pneumococcal chromosomal DNA, and DNA fragments that remained associated with the beads at elevated salt concentrations were assumed to interact specifically with CiaR. DNA of the S. pneumoniae strain KNR.7/87 was used in the binding assay, since the oligonucleotide microarray was based on the genomic sequence of that strain, which differs from the R6 strain by almost 10% of the genes (21). The ciaR gene of KNR.7/87 is identical to that of the R6 strain and is also highly conserved within the pneumococcal population (our unpublished results). Therefore, the target sequences could also be expected to be conserved. Since it is possible that a CiaR binding site is lost if it is located close to a restriction site, independent assays were performed using three distinct restriction digests. The enzymes RsaI and Sau3A produced relatively small fragments (<5 kb), whereas those generated with HindIII ranged from 1 to approximately 20 kb (Fig. 1). In all three cases, a reproducible pattern of specific fragments eluted from the bCiaR-coated beads with between 11 and 17 bands clearly identifiable (Fig. 1). The size of the targeted fragments ranged from 1 to ∼15 kb for HindIII and from 4.5 kb and smaller for Sau3A and RsaI.

FIG. 1.

Visualization of CiaR target fragments obtained with RsaI-, Sau3A-, and HindIII-restricted chromosomal DNA of S. pneumoniae. DNA fragments obtained after specific elution from bCiaR-coated magnetic beads were separated on a 1% agarose gel, stained with SYBRgreen, and visualized with the help of a fluoroimager. Three different restriction digests were used: Sau3A1, HindIII, and RsaI. Lanes: a, total restricted chromosomal DNA; b, DNA fragments obtained after specific elution in the SPDB assay; c, high-mass DNA ladder marker; d, size ladder marker.

Characterization of CiaR target regions.

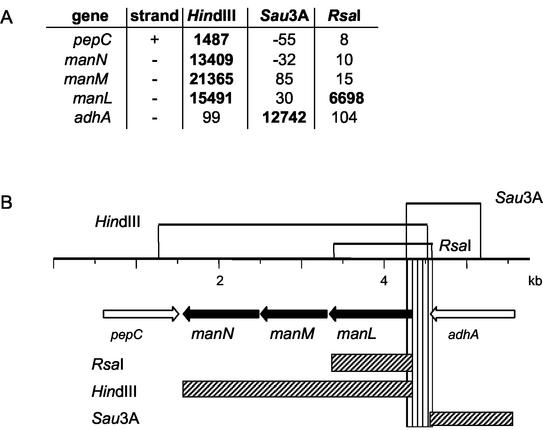

After hybridization to the oligonucleotide microarray, the DNA fragment sequences corresponding to the fluorescent signals resulting from each of the three restriction digests were aligned according to the published KNR.7/87 genome sequence (52). Positive signals that covered exclusively repetitive elements, such as transposons and insertion sequence elements, were not taken into account. The 41 regions detected with at least two or all three sets of restriction fragments were investigated in detail. Using the published genome of strain KNR.7/87 as the basis for a restriction map, the region of interest was examined to see whether the fluorescent signals coincided with the predicted restriction fragments. As an example, the region that includes the manLMN operon encoding an orthologue of the mannose-specific PTS system previously described in Streptococcus salivarius (32) is shown in Fig. 2. The signals obtained with the HindIII and RsaI restriction fragments were located in the man genes, whereas the Sau3A1-derived signal was located upstream of the man operon. One should keep in mind that the probe sets on the microarray do not necessarily cover the full-length gene, and the promoter region of the man operon is not represented on the microarray. The restriction map for HindIII, Sau3A1, and RsaI deduced from the KNR.7/87 genome shows that the fluorescent signals match the predicted restriction fragments and that the only area overlapping in all three fragments covers the entire intergenic region located upstream of the manL gene. It was thus concluded that a CiaR binding site is located in the man operon regions, suggesting that manLMN may be one of the cia-regulated gene loci.

FIG. 2.

Restriction analysis versus microarray hybridization signals of the manLMN region. (A) The numbers in the table indicate fluorescence intensities for each of the probe sets for the manLMN cluster and flanking genes. Positive fluorescent signals are written in boldface. (B) Restriction fragments expected from the map of the S. pneumoniae genome are indicated by lines drawn above the genetic organization of the putative target region. The regions covered by the positive fluorescent probe sets of the microarray are indicated by hatched blocks at the bottom. The vertically hatched area represents the minimal overlapping region of all three deduced restriction fragments. Solid arrows indicate the suggested cia-regulated man operon.

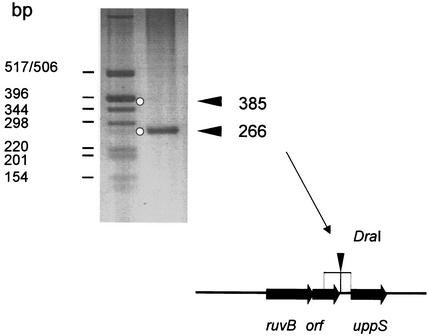

Specificity of binding was confirmed for several fragments by testing them individually in the SPDB assay in the presence of competitor DNA as shown in Fig. 3 for the region upstream of the uppS gene. The Sau3A fragment covering the region upstream of the uppS gene and the gene downstream of ruvB (see Fig. 5) was PCR amplified and shown to contain a unique DraI site. Only the smaller 266-bp DraI fragment immediately upstream of uppS was retained by bCiaR, whereas neither the larger DraI fragment nor the competitor DNA remained bound (Fig. 3). Other regions tested for CiaR binding included those identified on fragments 14 and 15, and in both cases binding specificity could be confirmed in the SPDB assay (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Specificity of the SPDB assay. The region upstream of the uppS gene was PCR amplified and restricted with DraI as shown in the diagram below. Left lane, fragments mixed with competitor DNA (molecular size marker); right lane, fragments retained by bCiaR after elution and concentration by precipitation (see Materials and Methods). The two DraI fragments, I and II, are indicated on the right and are marked by open circles in the agarose gel. The sizes of the fragments are indicated on the left.

FIG. 5.

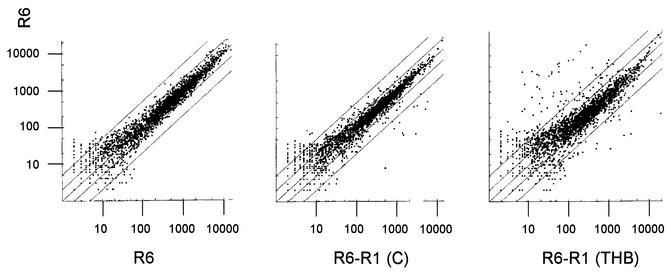

Genes regulated by the cia system. The intensity scatter graph shows the correlation for the intensities of all transcripts obtained for the loss-of-function cia mutant R6-R1 versus those of R6 in C medium (center) and in THB medium (right). A comparison between two independently grown R6 cultures in C medium is included as a control (left). The two lines flanking the diagonal indicate differences of a factor of 2 and 5, respectively. In the center graph, several genes are downregulated in the mutant. In addition, a large set of genes appears to be upregulated in THB medium (right).

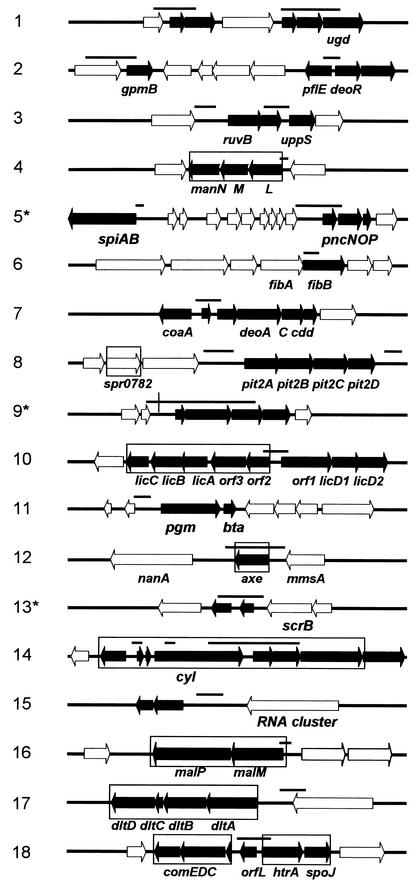

Altogether, 26 of the 41 analyzed fragments with positive hybridization signals for all three restriction digests contained matching restriction sites. The final list of 18 chromosomal locations, 7 of which contain more than one CiaR binding site, is shown in Table 1, and the genetic organization of a 10-kb region covering these sites is presented in Fig. 4. For most regions, the functions of the predicted cia target genes were known or could be inferred from significant sequence homologies (identity in all cases was >40% for the complete coding sequence [Table 1]). Many of the genes, some of which are essential, relate to cell wall polysaccharide metabolism. There are systems required for sugar uptake and utilization (manLMN and malPQ), glycosyltransferases of unknown specificity (region I), and modifying enzymes, such as a homologue of a xylan esterase, Axe. The gene products of deoAC are involved in ribose metabolism and are important for maintaining the nucleotide pool required for activation of sugar compounds in the cytoplasm. The undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthetase UppS is a key enzyme required for translocation of cell wall polysaccharide precursors through the cytoplasmic membrane. FibB (also called MurN) is involved in interpeptide bridge formation in the murein. The lic locus is involved in phosphoryl choline metabolism, with choline being a pneumococcus-specific component of the wall teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid. The dlt cluster is responsible for D alanylation of lipoteichoic acid in Streptococcus mutans. There are several transport systems (regions 8 and 15) and gene clusters involved in the production of biologically active peptides, such as the bacteriocin cluster spi (region 5) and a cluster encoding homologues of the Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin locus cyl (region 14). HtrA functions as an extracellular protease responsible for the degradation of abnormally folded export proteins in the closely related organism Lactococcus lactis. None of these gene products has been related to genetic competence so far, and no obvious link to competence could be deduced from their putative functions.

TABLE 1.

Putative target regions of CiaR

| Region | Gene(s)a | Reference | Position

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNR7./87 | R6 | |||

| 1 | Hypothetical; ugd* | SP0133-SP0137 | spr0135-spr0137 | |

| 2 | gpmB*, pflE*, deoR* | SP0239-SP0247 | spr0218-spr0228 | |

| 3 | ruvB*, uppS | 4 | SP0256-SP0262 | spr0237-spr0241 |

| 4 | manLMN* | 28, 32 | SP0281-SP0285 | spr0258-spr0262 |

| 5 | spiAB, pnc (blp) cluster | 13, 45 | SP0524-SP0533 | spr0461-spr0466 |

| 6 | fibB (murN) | 15, 55 | SP0611-SP0617 | spr0537-spr0542 |

| 7 | deoAC* | 6 | SP0839-SP0845 | spr0741-spr0747 |

| 8 | pit2ABCD | 8 | SP1030-SP1037 | spr0933-spr0939 |

| 9 | Hypothetical | SP1057-SP1067 | Upstream of spr0973 | |

| 10 | orf2 and -3, licABC | 61 | SP1266-SP1274 | spr1143-spr1152 |

| 11 | pgm*, bta* | SP1694-SP1499 | spr1349-spr1352 | |

| 12 | axe* | 12 | SP1694-SP1697 | spr1537-spr1539 |

| 13 | sacA | Downstream of SP1795 | Downstream of spr1617 | |

| 14 | cyl | 60 | SP1945-SP1954 | spr1762-spr1771 |

| 15 | Hypothetical; 23S RNA | 60 | SP2001-SP2005 | spr1815-spr1818 |

| 16 | malPM | 39 | SP2104-SP2108 | spr1914-spr1918 |

| 17 | dltABCD* | 7 | SP2173-SP2178 | spr1979-spr1983 |

| 18 | orfL, htrA*, spo0J* | 16, 41 | SP2234-SP2240 | spr2040-spr2046 |

*, homologue.

FIG. 4.

Putative CiaR target regions. The putative CiaR target regions are listed according to their positions on the S. pneumoniae genome (see Table 1 for details). The regions representing the set of reactive probe sets that are present in the different restricted DNA samples are represented by bars above the genetic organization. Putative cia target genes are represented by solid arrows. The boxed segments indicate cia-dependently regulated genes (see Table 2).

cia-dependent gene expression.

In order to prove that the regions identified above include cia-regulated gene loci, the transcript profiles of cia mutants that had been generated in the laboratory strain R6 were compared to that of the parental R6 strain. In mutant R6-R1, the ciaR gene was disrupted by insertion of a spectinomycin resistance cassette (see Materials and Methods). This mutant produces neither a functional CiaR nor CiaH, since both genes are transcribed as an operon and CiaH-specific antibodies failed to detect the protein (17, 60).

The second mutant, R6ciaHC306, contains a point mutation in CiaH, T230>P, close to the conserved His226 (19); it was obtained by transformation of the ciaHC306 allele into the R6 strain. It has been suggested that this mutation affects the phosphatase activity of CiaH, resulting in overphosphorylation of CiaR (19). Thus, both mutants should allow a comparison of the expression profile of a cia-off situation (R6-R1) to that of a cia-on situation (R6ciaHC306).

In order to also be able to test the effects of cia mutations on the expression of the competence regulon, the experiments were performed in two different growth media. In C medium, which is routinely used in our laboratory, the parental strain, R6, is fully competent whereas the R6ciaHC306 mutant is not; these conditions were therefore used to see whether the competence genes were suppressed by the ciaH mutation and, if so, which of them were affected. In contrast, in THB the R6 strain does not develop competence whereas the off mutant R6-R1 does.

Average intensity difference ratios of >3 were considered significant. The results generated in two or three independent experiments are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, and the observed changes in expression profiles of R6-R1 versus R6 are visualized in the intensity scatter graph in Fig. 5.

TABLE 2.

cia-regulated gene loci

| Clustera | Geneb | SPDBc | Gene expression compared to R6

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R6-R1 | R6ciaHC306 | |||

| 4 | man (3) | + | More | Less |

| 10 | lic (5) | + | Less | Samed |

| 12 | axe (1) | + | Less | More |

| 14 | cyl (7) | + | More | Same |

| 16 | mal (2) | + | Less | More |

| 17 | dlt (4) | + | Less | More |

| 18 | htrA-spo0J (2) | + | Less | More |

| 1 | cia (2) | − | NDe | More |

| 2 | spr0782 (SP0879) | − | Less | More |

| 3 | spr0931 (SP1027) | − | Less | More |

| Manyf | Competence regulon | − | More | Less |

Number refers to nomenclature used in Table 1.

Number in parentheses are numbers of genes in the operons.

Gene identified (+) or not identified (−) an DNA fragments isolated in SPDB assay.

Identical within the threefold threshold (see the text).

ND, not determined; due to the insertion in the ciaR gene, the negative value obtained in R6-R1 is not meaningful.

See table 3.

TABLE 3.

Competence-related cia-regulated genes

| Operon | Genea | Referenceb | Genomic position

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNR.7/87 | R6 | |||

| 1 | ccs1 | 43, 47 | SP0124 | spr0127 |

| ccs15 | SP0125 | spr0128 | ||

| 2 | clpB | SP0338 | spr0307 | |

| 3 | orfA | SP0428 | spr0387 | |

| orfB | SP0429 | spr0388 | ||

| orfC | SP0430 | spr0389 | ||

| 4 | celA (cilE) | 2, 9, 30, 42 | SP0954 | spr0856 |

| celB | 3, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP0955 | spr0857 | |

| orfD | SP0956 | spr0858 | ||

| orfE | SP0957 | spr0859 | ||

| orfF | SP0958 | spr0860 | ||

| 5 | coiA | 3, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP0978 | spr0881 |

| 6 | radC | 47 | SP1088 | spr0996 |

| 7 | smf (cilB) | SP1266 | spr1144 | |

| 8 | pilD | 47 | SP1808 | spr1628 |

| 9 | ssbB (cilA) | 2, 9, 30, 42 | SP1908 | spr1724 |

| 10 | lytA | SP1937 | spr1754 | |

| dinF | SP1939 | spr1756 | ||

| recA | 2, 9, 30, 42 | SP1940 | spr1757 | |

| cinA | 3, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP1941 | spr1758 | |

| 11 | orfG | SP1945 | spr1762 | |

| 12 | comX2 | 5, 43 | SP2006 | spr1819 |

| 13 | CPIP788 | 5, 43 | SP2017 | spr1830 |

| 14 | orf1 | SP2047 | spr1857 | |

| cglE | 3, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP2048 | spr1859 | |

| cglD | SP2050 | spr1861 | ||

| cglC | SP2051 | spr1862 | ||

| cglB | SP2052 | spr1863 | ||

| cglA (cilD) | 2, 3, 9, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP2053 | spr1864 | |

| 15 | cbpD | 43, 47 | SP2201 | spr2006 |

| 16 | comFC (cflB) | SP2207 | spr2012 | |

| comFA (cflA) | 3, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP2208 | spr2011 | |

| 17 | comE | 43 | SP2235 | spr2041 |

| comD | SP2236 | spr2042 | ||

| 18 | comX1 | 3, 5, 30, 37, 41, 42 | SP0014 | spr0013 |

| 19 | orfK | SP0029 | spr0030 | |

| ccs16 | 43 | SP0030 | spr0031 | |

| 20 | comA | 3, 5, 30, 37, 41-43, 47 | SP0042 | spr0043 |

| comB | SP0043 | spr0044 | ||

orfA to orfK encode hypothetical proteins of unknown function.

Competence-related expression studies.

In C medium, 16 genes located in five loci were affected in the R6-R1 mutant compared to the R6 strain. These included the lic operon, the htrA-spo0J homologues, and the cyl region, all of which were isolated in the SPDB assay, as well as two open reading frames of unknown function (Table 2). The two cia genes were not taken into consideration, since the insertion duplication mutagenesis within ciaR obviously affects both ciaR and ciaH transcripts. Both the wild type and the R6-R1 mutant develop competence in C medium, and no change in competence-regulated genes was apparent between the two strains under these growth conditions (Fig. 5, center).

In THB medium, in addition to the genes that were differentially expressed in C medium, another four operons, or 10 genes, were affected in R6-R1 versus R6, all of which were located in the vicinity of putative CiaR target sites: the axe homologue, the malPQ operon, and the dlt operon (Table 2), which were all expressed at lower levels than in the R6 strain, and the manLMN operon, which was apparently upregulated. Furthermore, a large number of genes were upregulated, i.e., derepressed, in the absence of CiaR-CiaH, all of which are listed in Table 3. These genes include known early and late competence genes (Table 3), and all were induced upon addition of CSP (N. Balmelle, unpublished results), i.e., all of them belong to the competence regulon (Fig. 5, right). None of these genes was located in a region close to a putative CiaR target site with the exception of the comCDE operon, which is located approximately 1 kb upstream of the htrA locus.

This data set was complemented by the expression profile of the R6ciaHC306 mutant: genes that were downregulated in the absence of cia were upregulated in this mutant and vice versa (Tables 2 and 3). In addition both, ciaR and ciaH appeared to be upregulated in R6ciaHC306, in agreement with the autoregulation of the cia operon (17). The results clearly confirm that the ciaHC306 allele activates the cia system. All genes of the competence regulon as defined in the previous paragraph were repressed in the mutant in C medium.

The putative CiaR target fragments identified by the SPDB assay were examined further in detail. Four loci (regions 1, 2, 13, and 15) were silent in all experiments; the bacteriocin cluster in region 5 was lacking in the R6 strain. The remaining six loci (3, 6 to 9, and 11) were expressed in all strains but apparently not cia regulated under the conditions used.

In summary, the data suggest that CiaR acts as a positive regulator for most directly cia-regulated genes but as a negative regulator for the man and the cyl genes and that the competence regulon is also—directly or indirectly—controlled by the cia system.

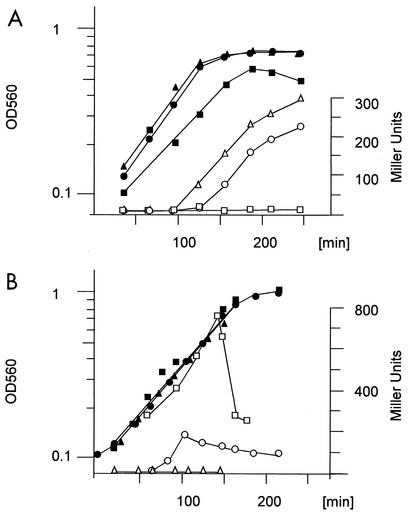

cia-dependent regulation of lic, dlt, and comC promoters.

To confirm the cia-dependent expression, the expression profiles of the lic and dlt promoters were examined in detail during the growth cycle in the wild type versus cia mutants (R6-R1 and ciaHC306). These two promoters were chosen because both are assumed to encode functions related to teichoic acid chemistry, using a lacZ reporter system as described previously (11, 59). The expression of lacZ production was monitored throughout the growth cycle. The lic promoter was induced at the end of the exponential growth phase in the wild-type R6 strain (Fig. 6A), whereas the loss-of-function mutants showed no detectable expression. In contrast, the R6ciaHC306 mutant showed expression at earlier time points and at higher levels than the R6 strain. Similar results were obtained for dlt constructs (not shown).

FIG. 6.

β-Galactosidase assay of the cia-dependent activation of the lic promoter (A) and the comC promoter (B). Construction of the lacZ reporter strains is described in Materials and Methods. Cultures were grown at 37°C in THB (A) or C medium (B). Samples were taken at the time points indicated, and the assay of β-galactosidase activity was performed as described in the text. Circles, R6; squares, R6-R1; triangles, R6TC306; solid symbols, growth (optical density at 560 nm [OD560]); open symbols, LacZ activity (Miller units).

The comC promoter was also investigated in detail in the R6-R1 background, as well as in the ciaHC306 mutant, under conditions where R6 develops competence (Fig. 6B). The expression of comC::lacZ was followed throughout the growth cycle. The R6 strain develops a broad peak of competence under these conditions, whereas the ciaHC306 mutant remains completely noncompetent throughout the growth cycle (11). In the present experiment, transformation efficiency was controlled at two cell densities at which competence in wild-type R6 is high. In the R6 background, comC-dependent LacZ activity remained low early during exponential growth and increased rapidly, consistent with the appearance of competence. Maximal expression was reached after approximately 20 min; it then decreased and remained at an elevated level until the onset of the stationary phase. In the ciaHC306 mutant that remained completely noncompetent, LacZ activity was not detectable throughout the growth cycle. In contrast, the loss-of-function mutant R6-R1, which was as competent as the R6 strain, showed a very high level of lacZ expression even at low cell density, reaching a maximum during late exponential growth.

DISCUSSION

The regulon of the TCSTS ciaR-ciaH was analyzed by a combination of two experimental approaches: DNA target fragments of the response regulator CiaR were isolated in a solid-phase DNA binding assay, and the gene expression pattern of cia mutants representing off and on stages of the cia system were compared to that of the parental R6 strain. In both cases, oligonucleotide microarray technology was used to identify the isolated DNA fragments and the transcripts, respectively. The overall picture revealed that the cia system is part of a complex regulatory network: it not only regulates genes directly in a positive or negative way but also controls the entire competence regulon. The com regulon is composed of the quorum-sensing system comCDE, which not only mediates its own autoregulation but also induces early competence genes, among which are the ComX regulators controlling late competence genes (30).

The method used here for identification of CiaR binding sites—a modified procedure developed for isolating target DNA fragments of DNA binding proteins—is certainly applicable to other response regulators and transcription regulators in general, provided that the protein construct is sufficiently stable during the incubation and washing steps necessary to obtain the desired specificity for DNA binding. The high reproducibility of the DNA fragment pattern obtained after the SPDB assay supports the specificity of the DNA-protein interaction, which was confirmed using isolated target fragments in the presence of competitor DNA (Fig. 3). The number of putative target regions identified after hybridization to the oligonucleotide microarray corresponds well to the number of bands contained in the SPDB-eluted fraction. We used a high level of stringency for discrimination of DNA fragments specifically interacting with the CiaR protein. Due to the presence of nonspecific background after the SPDB assay, the noise level was set relatively high compared to previous studies (21). The use of three distinct restriction digests in the SPDB assay allowed the easy discrimination of apparent positive regions: in some cases, positive signals were restricted to only one of the restriction digests and further discrimination was achieved by comparing the restriction map of the apparent positive fragments with the locations of the positive probe sets.

Although many of the putative cia target loci identified by direct interaction of DNA fragments with CiaR were detected in the transcription-profiling approach, some were not (and seen in the transcription analysis were not revealed as target genes by the SPDB assay). Five of the gene loci were not expressed under any conditions or were absent in the R6 strain. It has been shown recently that different methods employed in studies defining the Bacillus subtilis σW-regulated genes never covered the entire regulon and never overlapped completely (10), and a similar conclusion can be drawn from the present study with the cia regulon. Two gene loci were not detected in the SPDB assay although they were clearly expressed in a cia-dependent manner. It is possible that the putative binding site for CiaR is restricted by all three enzymes used in this assay or that they are indirectly controlled by the cia system. It should also be pointed out that we used nonphosphorylated bCiaR in the assay. Attempts to phosphorylate the protein were unsuccessful due to the instability of the biotinylated fusion derivative bCiaR under these conditions. However, although phosphorylation may result in a higher affinity to the binding sites, the specificity should not be affected, and the fact that cia-dependent expression was observed for targeted loci is in agreement with this conclusion. Computer searches were unsuccessful in identifying a consensus binding site for CiaR for all cia-regulated genes, which may not be surprising given the low level of strictly conserved nucleotides in several known binding sites of response regulators, and one has to await direct binding studies, e.g., footprint analyses.

Loss-of-function mutants are often without significant phenotype, and since they represent constitutive situations, transcription analyses do not distinguish between primary and secondary regulated genes. It required the combination of the two experimental approaches, direct DNA binding and transcript analyses, as well as two sets of mutants, the R6-R1 mutant with a nonfunctional cia system and the kinase mutant R6ciaHC306 reflecting an on situation, in order to be able to distinguish between primary and secondary regulated genes and to confirm gene induction or repression in the cia mutants relative to the wild-type situation. By using two different growth media (C medium and THB), it became apparent that the regulation machinery is also modulated under different environmental conditions and thus perhaps in different in vivo situations as well. This could be the reason for distinct results obtained with loss-of-function cia mutants using two different murine models. In only one case, where the development of pneumonia after intranasal inoculation was tested, was virulence clearly affected in the mutants (53), whereas no effect was detected in an intraperitoneal-infection model (27).

The cia system may also be differentially activated during the growth cycle, as could be seen for the dlt and lic operons, both of which were expressed only during late exponential growth in the wild type. The gene products of both loci are involved in teichoic acid metabolism. Stationary-phase cells are known to have a biochemically distinct cell envelope (18, 54), and it is conceivable that cia is one of the mediators of such changes. This experiment also indicates that detailed kinetic analyses of all the cia-dependent gene loci identified here, preferably in different growth media, would be helpful. It is possible that the failure to detect cia-dependent gene expression for some loci identified as CiaR targets is related to the fact that samples were taken during exponential growth phase and not during stationary phase. The microarray used in the present study is no longer available. Further tests thus have to wait for another generation microarray or will require the isolation of reporter constructs or real-time PCR for the other gene loci.

The putative target genes cover a whole range of functions related to cell wall polysaccharide biochemistry. We do not know yet whether the phenotype of ciaH mutants—increased beta-lactam resistance—is due to one particular gene product or is a reflection of an overall change in cell wall biochemistry mediated by the cia regulon. The twofold increase in the MIC of cefotaxime for ciaH mutants was observed in the wild-type background (from 0.02 to 0.04 μg/ml) and in mutants where pbp2x mutations had already resulted in elevated MICs (from 0.2 to 0.4 μg/ml), and these values are in the range conferred by single point mutations in penicillin binding protein genes (17, 58). Homologues of the enzymes pyrimidine-nucleoside phosphorylase and deoxyribose phosphate aldolase are required for pyrimidine biosynthesis and feed into the precursor pool of XTP-activated sugar compounds. The enzymes phosphoglycerate mutase and pyruvate formate lyase play key roles in the glycolytic pathway. It has been shown that glycolytic intermediates differ in exponential- and stationary-phase growth and that these changes correlate with the production of exopolysaccharide in L. lactis (44). It is curious that two cia-regulated loci encode enzymes involved in teichoic acid biosynthesis or modification: the lic locus is required for phosphoryl choline metabolism, and the dlt locus is involved in D alanylation in related bacteria. No D alanylation of teichoic acids has been observed in S. pneumoniae (W. Fischer, personal communication). The activation of the dlt operon occurred only in certain media and only at the end of exponential growth, and it is possible that the failure to detect D alanylation of teichoic acids is related to analyzing cells grown under conditions where the dlt operon is not active.

What is the link between the directly cia-regulated genes and the cia-mediated effect on competence? None of the competence-regulated gene loci was targeted by CiaR, whereas the transcript analyses clearly documented a complete repression of competence genes in the ciaHC306 mutant background, which was reflected in more detail in the comC promoter-lacZ fusion (Fig. 6B). The competence deficiency mediated by ciaH mutations could be complemented by the addition of CSP, the comC gene product responsible for the induction of the competence regulon (60). It has recently been suggested that HtrA is involved in cia-mediated inhibitory control over the competence pathway (49). However, a loss-of-function htrA mutant did not restore competence in the R6 strain when tested in THB medium, where the cia system appears to be activated (M. Merai, unpublished results), suggesting that it is not the HtrA protease itself that is responsible for the inhibition of competence. The comCDE operon region is located approximately 1 kb upstream of the htrA-spo0J locus, which contains a CiaR binding site. It is possible that the repression of competence under cia-activating conditions is due to interference with ComE binding to the comC promoter region. Alternatively, competence induction might be prevented by cia-mediated altered surface properties that could interfere with sufficient CSP production or recognition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Walter Messer for the gift of plasmid pBEX5BA, Jean-Pierre Claverys for plasmid pEVP3, and Don Morrison for pXF520.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Schwerpunkt für Biotechnologie of the University of Kaiserslautern.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaberge, I. S., J. Eng, G. Lermark, and M. Lovik. 1995. Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae in mice: a standardized method for preparation and frozen storage of the experimental bacterial inoculum. Microb. Pathog. 18:141-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alloing, G., C. Granadel, D. A. Morrison, and J.-P. Claverys. 1996. Competence pheromone, oligopeptide permease, and induction of competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 21:471-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alloing, G., B. Martin, C. Granadel, and J.-P. Claverys. 1998. Development of competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae: pheromone autoinduction and control of quorum sensing by the oligopeptide permease. Mol. Microbiol. 29:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apfel, C. M., B. Takács, M. Fountoulakis, M. Stieger, and W. Keck. 1999. Use of genomics to identify bacterial undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthetase: cloning, expression, and characterization of the essential uppS gene. J. Bacteriol. 181:483-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartilson, M., A. Marra, J. Christine, J. S. Asundi, W. P. Schneider, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2001. Differential fluorescence induction reveals Streptococcus pneumoniae loci regulated by competence stimulator peptide. Mol. Microbiol. 39:126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolotin, A., O. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Marlarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd, D. A., D. G. Cvitkovitch, A. S. Bleiweis, M. Y. Kiriukhin, D. V. Debabov, F. C. Neuhaus, and I. R. Hamilton. 2000. Defects in d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid synthesis in Streptococcus mutans results in acid sensitivity. J. Bacteriol. 182:6055-6065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, J. S., S. M. Gilliland, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenicity island encoding an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40:572-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, E. A., S. Y. Choi, and H. R. Masure. 1998. A competence regulon in Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by genomic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 27:929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, M., P. A. Kobel, M. M. Morshedi, M. F. W. Wu, C. Paddon, and J. D. Helmann. 2002. Defining the Bacillus subtilis σW regulon: a comparative analysis of promoter consensus search run-off transcription macroarray analysis (ROMA), and transcriptional profiling approaches. J. Mol. Biol. 316:443-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claverys, J.-P., A. Dintilhac, E. V. Pestova, B. Martin, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. Construction and evaluation of new drug-resistance cassettes for gene disruption mutagenesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae, using an ami test platform. Gene 164:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degrassi, G., M. Kojic, G. Ljubijankic, and V. Venturi. 2000. The acetyl xylan esterase of Bacillus pumilus belongs to a family of esterases with broad substrate specificity. Microbiology 146:1585-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Saizieu, A., C. Gardes, N. Flint, C. Wagner, M. Kamber, T. J. Mitchell, W. Keck, K. E. Amrein, and R. Lange. 2000. Microarray-based identification of a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae regulon controlled by an autoinduced peptide. J. Bacteriol. 182:4696-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echenique, J. R., S. Chapuy-Regaud, and M. C. Trombe. 2000. Competence regulation by oxygen in Streptococcus pneumoniae: involvement of ciaRH and comCDE. Mol. Microbiol. 36:688-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipe, S. R., and A. Tomasz. 2000. Inhibition of the expression of penicillin-resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae by inactivation of cell wall muropeptide branching genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4891-4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasc, A.-M., P. Giammarinaro, S. Richter, and M. Sicard. 1998. Organization around the dnaA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 144:129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giammarinaro, P., A. M. Sicard, and A.-M. Gasc. 1999. Genetic and physiological studies of the CiaH-CiaR two-component signal-transducing system involved in cefotaxime resistance and competence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 145:1859-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glauner, B., J.-V. Höltje, and U. Schwarz. 1988. The composition of the murein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:10088-10095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guenzi, E., A. M. Gasc, M. A. Sicard, and R. Hakenbeck. 1994. A two-component signal-transducing system is involved in competence and penicillin susceptibility in laboratory mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 12:505-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guenzi, E., and R. Hakenbeck. 1995. Genetic competence and susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 are linked via a two-component signal-transducing system, p. 125-128. In J. J. Ferretti, M. S. Gilmore, T. R. Klaenhammer, and F. Brown (ed.), Genetics of Streptococci, Enterococci and Lactococci. S. Karger AG, Basel, Switzerland. [PubMed]

- 21.Hakenbeck, R., N. Balmelle, B. Weber, C. Gardes, W. Keck, and A. de Saizieu. 2001. Mosaic genes and mosaic chromosomes: intra- and interspecies variation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69:2477-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakenbeck, R., T. Grebe, D. Zähner, and J. B. Stock. 1999. β-Lactam resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: penicillin-binding proteins and non-penicillin-binding proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 33:673-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakenbeck, R., A. König, I. Kern, M. van der Linden, W. Keck, D. Billot-Klein, R. Legrand, B. Schoot, and L. Gutmann. 1998. Acquisition of five high-Mr penicillin-binding protein variants during transfer of high-level β-lactam resistance from Streptococcus mitis to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 180:1831-1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Håvarstein, L. S., G. Coomaraswamy, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11140-11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D. J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P. M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. J. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacks, S. A., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1960. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme activity in pneumococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 39:508-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange, R., C. Wagner, A. de Saizieu, N. Flint, J. Molnos, M. Stieger, P. Caspers, M. Kamber, W. Keck, and K. E. Amrein. 1999. Domain organization and molecular characterization of 13 two-component systems identified by genome sequencing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene 237:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau, G. W., S. Haataja, M. Lonetto, S. E. Kensit, A. Marra, A. P. Bryant, D. McDevitt, D. A. Morrison, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A functional genomic analysis of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40:555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeBlanc, D. J., L. N. Lee, and J. M. Inamine. 1991. Cloning and nucleotide base sequence analysis of a spectinomycin adenyltransferase AAD(9) determinant from Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1804-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, M. S., and D. A. Morrison. 1999. Identification of a new regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae linking quorum sensing to competence for genetic transformation. J. Bacteriol. 181:5004-5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lockhart, D. J., H. Dong, M. C. Byrne, M. T. Follettie, M. V. Gallo, M. S. Chee, M. Mittmann, C. Wang, M. Kobayashi, H. Horton, and E. L. Brown. 1996. Expression monitoring by hybridization to high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:1675-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lortie, L. A., M. Pelletier, C. Vadeboncoeur, and M. Frenette. 2000. The gene encoding IIAB(Man)L in Streptococcus salivarius is part of a tetracistronic operon encoding a phosphoenolpyruvate: mannose/glucose phosphotransferase system. Microbiology 146:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maes, M., and S. Messens. 1992. Phenol as grinding material in RNA preparations. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, B., M. Prudhomme, G. Alloing, C. Granadel, and J.-P. Claverys. 2001. Cross-regulation of competence pheromone production and export in the early control of transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 38:876-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 269:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Mortier-Barrière, I., A. de Saizieu, J.-P. Claverys, and B. Martin. 1998. Competence-specific induction of recA is required for full recombination proficiency during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 21:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murtif, V. L., C. R. Bahler, and D. Samols. 1985. Cloning and expression of the 1.3S biotin-containing subunit of transcarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:5617-5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieto, C., A. Puyet, and M. Espinosa. 2001. MalR-mediated regulation of the Streptococcus pneumoniae malMP operon at promoter PM. Influence of a proximal divergent promoter region and competition between MalR and RNA polymerase proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14946-14954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkinson, J. S. 1993. Signal transduction schemes of bacteria. Cell 73:857-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pestova, E. V., L. S. Håvarstein, and D. A. Morrison. 1996. Regulation of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae by an auto-induced peptide pheromone and a two-component regulatory system. Mol. Microbiol. 21:853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pestova, E. V., and D. A. Morrison. 1998. Isolation and characterization of three Streptococcus pneumoniae transformation-specific loci by use of a lacZ reporter insertion vector. J. Bacteriol. 180:2701-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson, S., R. T. Cline, H. Tettelin, V. Sharov, and D. A. Morrison. 2000. Gene expression analysis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae competence regulons by use of DNA microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 182:6192-6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramos, A., I. C. Boels, W. M. de Vos, and H. Santos. 2001. Relationship between glycolysis and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:33-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reichmann, P., and R. Hakenbeck. 2000. Allelic variation in a peptide-inducible two component system of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richter, S., W. R. Hess, M. Krause, and W. Messer. 1998. Unique organization of the dnaA region from Prochlorococcus marinus CCMP1375, a marine cyanobacterium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:534-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimini, R., B. Jansson, G. Feger, T. C. Roberts, M. de Francesco, A. Gozzi, F. Faggioni, E. Domenici, D. M. Wallace, N. Frandsen, and A. Polissi. 2001. Global analysis of transcription kinetics during competence development in Streptococcus pneumoniae using high density DNA arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1279-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth, A., and W. Messer. 1995. The DNA binding domain of the initiator protein DnaA. EMBO J. 14:2106-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sebert, M. E., L. M. Palmer, M. Rosenberg, and J. N. Weiser. 2002. Microarray-based identification of htrA, a Streptococcus pneumoniae gene that is regulated by the CiaRH two-component system and contributes to nasopharyngeal colonization. Infect. Immun. 70:4059-4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, M. D., and W. R. Guild. 1979. A plasmid in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 137:735-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stock, J. B., M. G. Surette, M. Levit, and P. Park. 1995. Two-component signal transduction systems: structure-function relationships and mechanisms of catalysis, p. 25-51. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 52.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. W. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. R. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Vetern, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Throup, J. P., K. K. Koretke, A. P. Bryant, K. A. Ingraham, A. F. Chalker, Y. Ge, A. Marra, N. G. Wallis, J. R. Brown, D. J. Holmes, M. Rosenberg, and K. R. Burnham. 2000. A genomic analysis of two-component signal transduction in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:566-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warth, A. D., and J. L. Strominger. 1972. Structure of the peptidoglycan from spores of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry 11:1389-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weber, B., K. Ehlert, A. Diehl, P. Reichmann, H. Labischinski, and R. Hakenbeck. 2000. The fib locus in Streptococcus pneumoniae is required for peptidoglycan crosslinking and PBP-mediated beta-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 188:81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wodicka, L., H. Dong, M. Mittmann, M. H. Ho, and D. J. Lockhart. 1997. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:1359-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young, R. A., and R. W. Davis. 1983. Yeast RNA polymerase II genes: isolation with antibody probes. Science 222:778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zähner, D., T. Grebe, E. Guenzi, J. Krauβ, M. van der Linden, K. Terhune, J. B. Stock, and R. Hakenbeck. 1996. Resistance determinants for β-lactam antibiotics in laboratory mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae that are involved in genetic competence. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zähner, D., and R. Hakenbeck. 2000. The Streptococcus pneumoniae beta-galactosidase is a surface protein. J. Bacteriol. 182:5919-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zähner, D., K. Kaminski, M. van der Linden, T. Mascher, M. Merai, and R. Hakenbeck. 2001. The ciaR/ciaH regulatory network of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:211-216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, J. R., I. Idanpaan-Heikkila, W. Fischer, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1999. Pneumococcal licD2 gene is involved in phosphorylcholine metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1477-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]