Abstract

In bacteria the biosynthetic pathways for purine mononucleotides and the hydroxymethyl pyrimidine moiety of thiamine share five reactions that result in the formation of aminoimidazole ribotide, the last metabolite common to both pathways. Here we describe the characterization of a Salmonella enterica mutant strain that has gained the ability to efficiently use exogenous aminoimidazole riboside (AIRs) as a source of thiamine. The lesion responsible for this phenotype is a null mutation in a transcriptional regulator of the GntR family (encoded by stm4068). Lack of this protein derepressed transcription of an associated operon (stm4065-4067) that encoded a predicted kinase. The stm4066 gene product was purified and shown to have AIRs kinase activity in vitro. This activity was consistent with the model presented to explain the phenotype caused by the original mutation. This mutation provides a genetic means to isolate the synthesis of the hydroxymethyl pyrimidine moiety of thiamine from the pathway for purine mononucleotide biosynthesis and thus facilitate in vivo analyses.

Characterization of biochemical pathways in vivo is facilitated by exogenously providing metabolic intermediates that can both be taken up by the cell and be fed into the appropriate pathway. Such an approach can be used to direct flux, overcome regulation, and dissect the biochemical details of a pathway. Exogenously feeding metabolites can also bypass the need for enzymatic steps and thus serves as a means to isolate specific parts of a pathway for in vivo study. This strategy can be particularly useful for isolating parts of branched pathways such as those for thiamine and purine biosynthesis.

The purine and thiamine biosynthetic pathways in Salmonella enterica as they are currently understood are shown in Fig. 1. These two biosynthetic pathways share five reactions that result in the formation of aminoimidazole ribotide (AIR), the last metabolite common to both pathways. AIR is the precursor of the pyrimidine moiety of thiamine, 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine phosphate (HMP-P). The synthesis of HMP-P involves a complex intramolecular rearrangement and requires the product of at least the thiC gene (for reviews see references 4 and 12). Metabolites that would be helpful to dissect the AIR-to-HMP-P pathway in vivo are unstable, commercially unavailable, or poorly taken up by S. enterica.

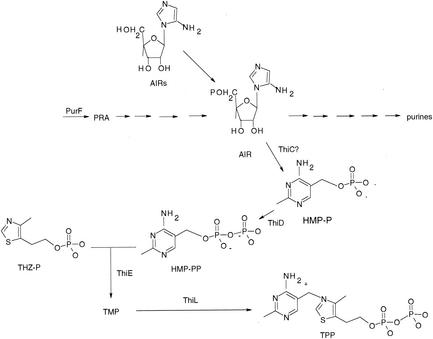

FIG. 1.

Purine mononucleotide and thiamine pyrophosphate biosynthetic pathways in S. enterica. Shown is a schematic representation of the biosynthetic pathways for purine mononucleotides and thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP). Relevant intermediates are indicated. The phosphorylation of AIRs to AIR by STM4066, allowing it to enter the pathway as an intermediate, is shown. When present, the gene products responsible for the various reactions are indicated near the step they catalyze. Abbreviations: PRA, phosphoribosylamine; THZ-P, thiazole phosphate; HMP-PP, 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine pyrophosphate.

In the historic work that identified the branched nature of the purine and thiamine pathways, Newell and Tucker took advantage of a metabolite feeding approach (21). These authors described derivatives of S. enterica strain LT2 that were able to use exogenous aminoimidazole riboside (AIRs) to satisfy the cellular requirement for both purines and thiamine (21). The mechanism by which this strain was able to incorporate this compound was not investigated, and further characterization of these mutants was not described.

We have previously reported the isolation of a spontaneous mutant derived from a purF mutant strain that had a 94-fold reduction of the amount of AIRs required to satisfy the cellular thiamine requirement (23). The use of this mutant strain has allowed us to nutritionally isolate the steps required for AIR-to-HMP-P conversion from the steps common to the purine and thiamine pathways (1). Neither this mutant nor any we have isolated in fairly exhaustive screens was able to use AIRs to satisfy a purine requirement, suggesting that the strain described by Newell and Tucker carried multiple lesions.

Here we report the characterization of an S. enterica strain that has the ability to efficiently use exogenous AIRs as a source of thiamine. The causative lesion in this strain is a null mutation in a transcriptional regulator of the GntR family. We show that loss of this regulator increased expression of an operon containing three genes. The nutritional phenotype described for this mutant required the overproduction of a single gene in this operon (stm4066) that encoded a kinase able to phosphorylate AIRs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and chemicals.

All strains used in this study are derivatives of S. enterica LT2 and are listed with their genotypes in Table 1. MudJ refers to the Mud1734 insertion element (8), and Tn10d(Tc) refers to the transposition-defective mini-Tn10 described by Way et al. (28). No-carbon E medium supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 (9, 27) and glucose (11 mM) was used as a minimal medium. When present in media, these compounds were used at the following concentrations: thiamine, 500 nM; adenine, 0.4 mM; AIRs, 1 mM. Difco nutrient broth (8 g/liter) with NaCl (5 g/liter) and Luria-Bertani broth (LB) were used as rich media. Difco BiTek agar (15 g/liter) was added for solid medium. Antibiotics were added as needed to the following concentrations in rich and minimal media, respectively: tetracycline, 20 and 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 and 125 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 and 4 μg/ml; ampicillin, 37 and 19 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strain and plasmid list

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or vector and insert | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| LT2 | Wild type | Laboratory strain |

| TT13270 | pnuE84::MudJ | SGSCa |

| DM1936 | purF2085 | Laboratory strain |

| DM2253 | purF2085 stm4068-1b | Laboratory strain |

| DM5999 | purF2085 zxx-9122::Tn10d(Tc) | |

| DM6000 | purF2085 stm4068-1 zxx-9122::Tn10d(Tc) | |

| DM6126 | purF2085 (pMD6) | |

| DM6127 | purF2085 (pMD7) | |

| DM6140 | purF2085 (pSU19) | |

| DM6180 | purF2085 stm4068-1 (pMD6) | |

| DM6317 | stm4066-3::Kn | |

| DM6483 | purF2085 stm4065-2::MudJ stm4068-1 | |

| DM6484 | purF2085 stm4065-2::MudJ | |

| DM6527 | purF2085 stm4068-1 (pMD10) | |

| DM6528 | purF2085 stm4068-1 (pMD11) | |

| DM6592 | purF2085 stm4065-4::Tn10d(Tc) (pMD6) | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD6 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4066c | 2 |

| pMD7 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4066d | |

| pMD8 | pT77 (Apr); stm4066c | 26 |

| pMD10 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4068c | |

| pMD11 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4068d | |

| pMD12 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4067c | |

| pMD13 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4067d | |

| pMD14 | pSU19 (Cmr); stm4065c |

SGSC, Salmonella Genetic Stock Center.

The stm gene designations are based on the annotated S. enterica genome.

Insert amplified by PCR from LT2 chromosomal DNA.

Insert amplified by PCR from DM2253 chromosomal DNA.

5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICARs) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc. (North York, Ontario, Canada). AIRs was synthesized from AICARs by the method of Bhat et al. without modification (5). IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was purchased from Fisher Biotech. [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from NEN Life Science (Boston, Mass.). [carbonyl-14C]NAD, DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow, and a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative grade column were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Restriction enzymes and DNA ligase were purchased from Promega (Madison, Wis.). Cloned Pfu DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.).

Genetic methods. (i) Transduction methods.

The high-frequency generalized transducing mutant version of bacteriophage P22 (HT105/1 int-201) (25) was used in all transductions. The methods for transduction and subsequent purification of transductants have been previously described (10).

(ii) Isolation of linked insertions.

Transposons [Tn10d(Tc) or MudJ] that were genetically linked to the lesion, allowing use of AIRs as a source of thiamine in strain DM2253, were isolated by standard genetic techniques (19). The chromosomal locations of the relevant insertions were determined by sequencing with a PCR-based protocol (7, 29). A DNA product was amplified with degenerate primers and primers derived from the Tn10d(Tc) or MudJ insertion sequences as described and sequenced by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center-Nucleic Acid and Protein Facility. Specifically, the MudJ insertion in stm4065 was located ∼400 nucleotides 3′ of the start codon.

(iii) Phenotypic analysis.

Nutritional requirements were assessed on solid medium with soft agar overlays and by quantification of growth in liquid media. Protocols for each have been previously described (3, 24).

Molecular biology techniques.

Open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified by PCR using Cloned Pfu DNA polymerase, and the appropriate primers are listed in Table 2. The resulting PCR products were purified and ligated into SmaI-cut pSU19. Plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α and screened for vectors containing inserts. Analysis of restriction digest patterns for the resulting plasmids was performed, and the identity and orientation of the inserts in these plasmids were confirmed by sequencing (Table 1). For DM2253, stm4066 was amplified from the chromosome eight independent times to confirm the identify of the causative mutation.

TABLE 2.

Primer list

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| STM4065-forward | CTCTCTTCATAGCCTCCA |

| STM4065-reverse | GGGCATTTCAGATAGCTG |

| STM4066-forward | TTTGGCGGCATCCTCTTC |

| STM4066-reverse | CACCAGGCATCCCAGTAT |

| STM4067-forward | GGACTGTTGTTCACCCTT |

| STM4067-reverse | AAGCGGAGTAAAGCTCGT |

| STM4068-forward | CGATTTGGCAGAACTGGC |

| STM4068-reverse | GGAACAGAGGATGGGACA |

| STM4066-forward-NdeI | GCGCATATGAAGGCCATGA |

| STM4066-reverse-stop | ATCAACGTGCATGATGACT |

Protein purification.

A plasmid (pMD8) containing stm4066 ligated into the NdeI and PstI sites of pT77 was constructed (26). The construct was confirmed by demonstration of the plasmid's ability to allow strain DM1936 (purF) to use AIRs as a source of thiamine. Cultures (25 ml) of E. coli strain BL21/λ(DE3) containing pMD8, grown overnight in LB with ampicillin (LB-AP), were used to inoculate 2 liters of LB-AP. The resulting culture was grown at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.8 (∼2 × 108 CFU), and IPTG (0.4 mM) was added. After 5 h at 30°C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and 7,500 × g for 15 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 30 ml of buffer A (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted with a French pressure cell (24,000 lb/in2). The crude extract was clarified by centrifugation at 4°C and 39,000 × g for 30 min. To remove the DNA, protamine sulfate was added over 20 min to a final concentration of 0.12%; after the solution was stirred for an additional 15 min, the precipitate was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was adjusted to 30% saturation by the addition of solid ammonium sulfate over 20 min, and the solution was stirred another 15 min and centrifuged to remove the precipitate. The supernatant was then adjusted to 50% saturation by the addition of solid ammonium sulfate over 20 min, and the solution was stirred another 15 min and centrifuged to remove the precipitate. The pellet was dissolved in 25 ml of buffer B (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) and desalted by passage through a Sephadex G-25 column (40 by 2.6 cm) equilibrated in buffer B. The fractions containing protein were pooled and loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow column (20 by 1.6 cm) equilibrated in buffer B. The column was washed with buffer B, and the protein was eluted with a 400-ml linear gradient from 0 to 500 mM NaCl in buffer B. STM4066 eluted at 250 mM NaCl. The fractions containing STM4066 were pooled, concentrated in an Amicon stirred cell, exchanged into buffer C (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl), and loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 preparative grade gel filtration column (60 by 1.6 cm). The protein was eluted with 180 ml of buffer C. The fractions containing the STM4066 protein were pooled, concentrated to 2 mg/ml, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)-20% glycerol overnight with two buffer changes, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Western blotting.

Western blot analysis was performed as described by Harlow and Lane (16). Strains were grown to 75 Klett units, pelleted, resuspended in 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and disrupted by sonication. Crude extracts were clarified by centrifugation, and 7 μg of total protein was loaded for each strain. Polyclonal rabbit antibodies against STM4066 and YggX were generated at the University of Wisconsin Animal Care Unit. Proteins were visualized by using horseradish peroxidase conjugated to an antirabbit secondary antibody (Promega) and the ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Enzyme assays. (i) AIRs kinase.

Mixtures for assaying AIRs kinase contained 100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM ATP containing 3 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, and various concentrations of AIRs in a final volume of 50 μl. The reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme: various amounts of extract or 2 μg of pure protein. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and 5 μl was spotted on a polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer chromatography plate (Selecto Scientific). Plates were developed with 0.7 M NH4Cl, pH 2.8, and analyzed by phosphorimagery (Molecular Dynamics).

(ii) NAD pyrophosphatase.

Strains to be analyzed (20 ml) were grown to 60 Klett units in minimal medium, centrifuged to pellet cells, and resuspended in 0.6 ml of 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0. The cells were disrupted with a Fisher Scientific 550 Sonic Dismembrator, divided into 200-μl samples, quickly frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. NAD pyrophosphatase assays were performed by a modification of the protocol described by Falconer et al. (13). The reaction mixture contained 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 3 mM NAD containing 0.1 μCi of [carbonyl-14C]NAD, and crude extract (25 to 50 μg of protein) in a final volume of 50 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and 5 μl was spotted on an LHPK Silica Gel 60 A thin-layer chromatography plate (Whatman). The plate was developed with a mobile phase of methanol-acetonitrile-tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (20:55:20) as described by Heard (17) and analyzed by phosphorimagery.

(iii) β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed by the method of Miller (20) as previously reported (11). β-Galactosidase units are defined as nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per minute.

RESULTS

Genetic mapping of the mutation allowing use of AIRs as a source of thiamine.

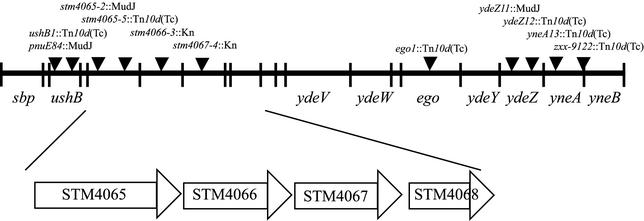

A mutation that allows mutants blocked in any of the first five steps in purine biosynthesis to use AIRs as a source of thiamine was previously described (23). For clarity, and based on results presented here, this mutant allele has been designated stm4068-1. Multiple transposon insertions linked to stm4068-1 were identified. A P22 lysate grown on a pool of cells containing transposon insertion Tn10d(Tc) or MudJ was used to transduce DM2253 (purF2085 stm4068-1) to tetracycline or kanamycin resistance, respectively. Approximately 200,000 antibiotic-resistant transductants were screened for those no longer able to grow on minimal glucose medium supplemented with adenine and AIRs. Genetic reconstruction experiments confirmed that eight independent transposons [six Tn10d(Tc) and two MudJ] were linked to the causative mutation. The chromosomal location of each transposon insertion was determined by sequencing with a PCR-based protocol using degenerate primers (see Materials and Methods). Additional linkage analyses and three-factor cross data generated with these strains focused attention on a small region of the chromosome at 88 min, containing five open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 2). The only insertion mutations shown in Fig. 2 that prevented the efficient use of AIRs were those in stm4065 and those in stm4066. This region is not present in the E. coli K-12 genome, and only one of the five genes (ushB, which encodes a UDP-sugar hydrolase) has a close homolog in E. coli (15). While four of the relevant ORFs were not annotated, one (the STM4066 ORF) encoded a putative kinase. The presence of this ORF stood out since AIRs must be phosphorylated prior to incorporation into the purine and thiamine biosynthetic pathways. In addition to the putative kinase, sequence analyses suggested the presence of a permease (STM4065), an ADP-ribosyl glycohydrolase (STM4067), and a GntR family transcriptional regulator (STM4068).

FIG. 2.

Relevant chromosomal region of the S. enterica chromosome. Presented is a representation of the chromosomal region of interest. Positions of the insertions that were linked to the lesion allowing utilization of AIRs in DM2253, as determined by sequencing, are indicated. The only insertions that eliminated the ability of DM2253 to utilize AIRs were those located in stm4065 or stm4066. The surrounding genes, as annotated (genome.wustl.edu/gsc/Projects/S.typhimurium), are indicated. STM designations are used for the products of ORFs that are not found in E. coli and that have not been annotated.

STM4066 in multicopy confers the ability to use AIRs as a source of thiamine.

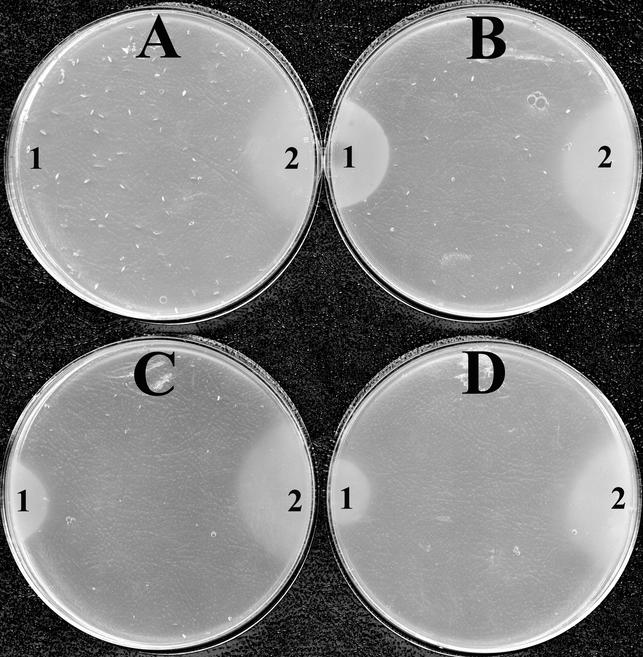

Three ORFs (the STM4065, STM4066, and STM4067 ORFs) were individually amplified by PCR from both wild-type and mutant backgrounds and ligated into the mid-copy-number vector pSU19 (2). The resulting six plasmids were electroporated into both DM1936 (purF2085) and DM2253 (purF2085 stm4068-1), and the resulting 12 strains were tested for their ability to use AIRs as a source of thiamine. The plasmids containing STM4065 or STM4067 ORFs produced no phenotypic change in either recipient strain. In contrast, when the plasmid carrying the STM4066 ORF from either genetic background was present, DM1936 (purF2085) was able to use AIRs as a thiamine source. The resulting growth compared to that of relevant control strains is shown in Fig. 3. The growth phenotype detected on solid medium was confirmed with liquid growth analyses. In this case the specific growth rates for strains grown in minimal glucose medium supplemented with adenine and AIRs were as follows: DM6140, 0.122; DM6126, 0.203; DM6127, 0.231; DM6180, 0.324. The same strains when provided with thiamine had the following specific growth rates: DM6140, 0.216; DM6126, 0.390; DM6127, 0.439; DM6180, 0.354. These results led to the conclusions that (i) STM4066 was involved in the ability of the cell to use AIRs as a thiamine source and (ii) the causative mutation did not affect the function of this protein. A simple model predicted that the causative mutation affected the level of STM4066.

FIG. 3.

Nutritional phenotype caused by overexpression of stm4066. Soft agar overlays on minimal glucose adenine medium were prepared as described previously (24). Strains contained in the soft agar are DM6140 (purF2085 [pSU19]) (A), DM6180 (purF2085 stm4068-1 [pSU19]) (B), DM6126 (purF2085 [pMD6]) (C), and DM6127 (purF2085 [pMD7]) (D). On each plate 100 nmol of AIRs in 3 μl (1) and 300 pmol of thiamine in 3 μl (2) were spotted.

A null allele of the STM4068 gene allows S. enterica to use exogenous AIRs as a source of thiamine.

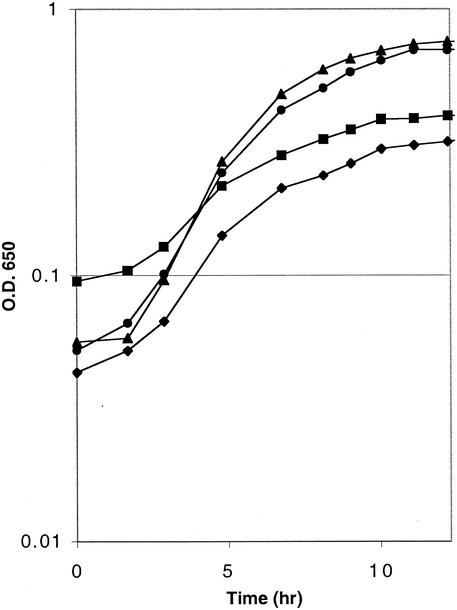

The transcriptional regulator in this region (STM4068) was a likely target for the causative mutation since it could affect the level of STM4066. To test this possibility, plasmids containing the STM4068 genes from both mutant (DM2253) and wild-type (DM1936) strains were generated. As the growth data shown in Fig. 4 demonstrate, a plasmid containing the STM4068 gene from a wild-type strain reduced the growth of strain DM2253 (purF stm4068-1) on medium containing adenine and AIRs (i.e., this plasmid complemented the mutant defect). The clone carrying the STM4068 gene from the mutant strain (DM2253) had no effect on the phenotype of either recipient. These results suggested that the causative mutation that allowed efficient use of AIRs as a source of thiamine was a lesion in stm4068 that eliminated its function.

FIG. 4.

Plasmid carrying the wild-type STM4068 gene reduces AIRs-dependent growth of purF mutant. Growth analyses were performed at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. Glucose minimal medium was supplemented with 0.4 mM adenine and 1 μM AIRs. Shown is the growth of strains DM6140 (purF2085 [pSU19]) (diamonds), DM6180 (purF2085 stm4068-1 [pSU19]) (circles), DM6527 (purF2085 stm4068-1 [pMD10]) (squares), and DM6528 (purF2085 stm4068-1 [pMD11]) (triangles). O.D.650, optical density at 650 nm.

The inserts from plasmids carrying the wild-type and mutant alleles of stm4068 were sequenced, as were the products of eight independent PCR amplifications of stm4068 from the chromosomes of wild-type and mutant strains. In each case, a single base pair was different between the two sequences, with the mutant allele of stm4068 carrying an AT-to-CG transversion relative to the wild type. In the context of the coding sequence, this base substitution generated a stop codon, truncating the final 67 amino acids of the 240-amino-acid gene product.

The STM4068 gene product acts as a repressor.

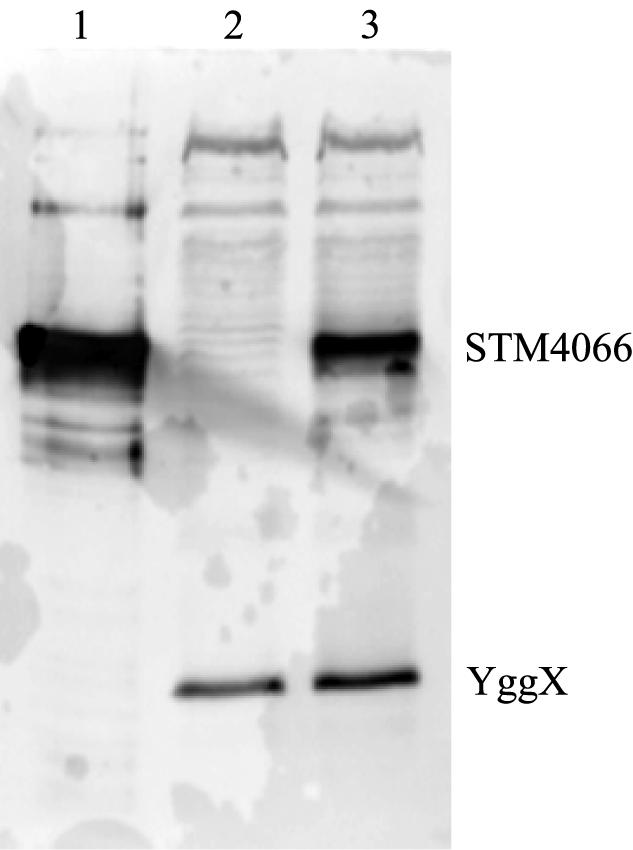

Isogenic strains containing a MudJ in stm4065 and either the wild-type or null allele of stm4068 were constructed. Sequence data indicated that the MudJ insertion was oriented such that transcription of lacZ was driven by the promoter for stm4065. Strains DM6483 (purF2085 stm4068-1 stm4065-2::MudJ) and DM6484 (purF2085 stm4065-2::MudJ) were grown in glucose medium supplemented with adenine and thiamine and then assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Under these growth conditions, transcription of the fusion in the wild-type strain was almost undetectable (0.26 ± 0.01 Miller units). However, the strain carrying the null allele of stm4068 increased transcription from the reporter more than 100-fold to 83 ± 4 Miller units. Addition of AIRs to the growth medium did not significantly alter these numbers (79 ± 8 and 0.23 ± 0.004 Miller units for DM6483 and DM6484, respectively). This result showed that, in the absence of the regulator, transcription of at least stm4065 was increased. To show that a strain lacking stm4068 overexpressed not only STM4065 but also STM4066, Western blotting was performed. Cell extracts of the wild-type and stm4068-1 null mutant strains were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and probed with polyclonal antibodies raised against the purified STM4066 protein. The results of these experiments, shown in Fig. 5, demonstrated that the stm4068 null mutation increased the accumulation of STM4066. Together these results are consistent with a three-gene operon structure and a regulatory function for STM4068.

FIG. 5.

STM4066 accumulates in a stm4068-1 mutant. Western blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, 50 ng of purified STM4066 protein; lanes 2 and 3, 7 μg of total cell protein from strains DM5999 [purF2085 zxx-9122::Tn10d(Tc)] and DM6000 [purF2085 stm4068-1 zxx-9122::Tn10d(Tc)], respectively. Antibodies to YggX were used as a loading control.

Functional STM4065 is not required for the utilization of AIRs.

The presence of a gene encoding a predicted permease in the same operon as the gene encoding the kinase required to utilize AIRs suggested that this permease might be required for transport of the AIRs prior to phosphorylation. To test the requirement for the permease in this process, a strain containing a Tn10d(Tc) insertion in STM4065 was transformed with a plasmid (pMD6) containing the stm4066 gene. The resulting strain (DM6592) was tested for growth on minimal glucose medium supplemented with adenine and AIRs. Efficient utilization of AIRs as a source of thiamine did not require STM4065, since the wild-type and stm4065-1 mutant strains carrying pMD6 had similar growth rates on this medium (data not shown). This result demonstrated that if STM4065 was a permease for AIRs, it was not the only one.

The STM4066 gene product has AIRs kinase activity.

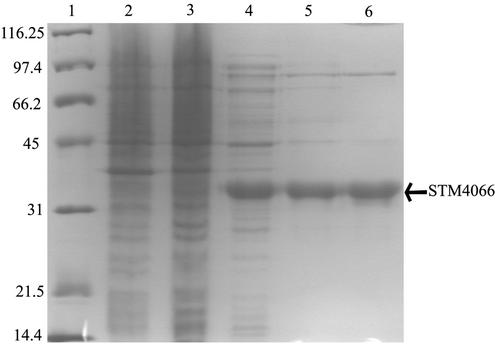

A simple model consistent with all the above data stated that (i) stm4066 encoded a protein with AIRs kinase activity, (ii) the stm4068-1 mutation resulted in increased expression of stm4066, and (iii) increased STM4066 generated sufficient AIR to satisfy the thiamine requirement of a mutant blocked in de novo purine biosynthesis. The STM4066 protein was purified to determine if it had AIRs kinase activity. The stm4066 coding region was cloned into the pT77 expression vector in an orientation for expression of the gene from the T7 promoter. The generated plasmid, pMD8, was electroporated into E. coli strain BL21/λ(DE3), and the resulting strain was used as a source of STM4066 protein for purification. Table 3 and Fig. 6 show the data for the purification of STM4066 as described in Materials and Methods. Analysis of SDS-PAGE data using Gel-Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.) indicated that STM4066 was >90% pure after gel filtration chromatography. Samples from each step of the purification were assayed for AIRs kinase activity as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 3.

Purification of STM4066

| Purification step | Protein amt (mg) | Activity (nmol/ min) | Sp act (nmol/ min/mg) | % Yield | Fold purifi- cation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 240 | 5,832 | 24.3 | 100 | 1 |

| Clarified crude extract | 258 | 5,934 | 23.0 | 102 | 0.95 |

| 30-50% (NH4)2SO4 fraction | 108 | 2,862 | 26.5 | 49 | 1.1 |

| DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow | 10.8 | 844.6 | 78.2 | 14 | 3.2 |

| Superdex 200 preparative grade | 3 | 413.1 | 137.7 | 7 | 5.7 |

FIG. 6.

Purification of STM4066. SDS-PAGE of the active fractions during STM4066 purification is shown. Lane 1, molecular mass standards (broad-range standard; Bio-Rad), with masses indicated in kilodaltons; lanes 2 to 6, crude extract, clarified crude extract, Sephadex G-25 eluate, DEAE-Sepharose eluate, and Superdex 200 eluate, respectively.

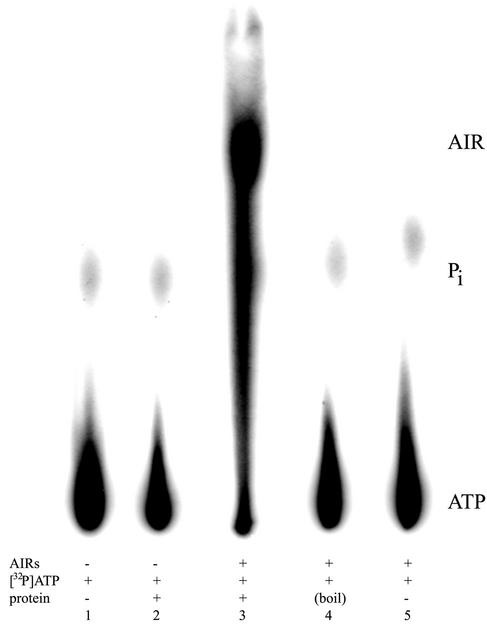

Data shown in Fig. 7 demonstrated that the STM4066 protein is capable of phosphorylating AIRs. This conclusion was supported by demonstration that control experiments lacking substrate (lane 2) or containing boiled protein (lane 4) or no protein (lane 5) failed to generate a phosphorylated compound. Additional experiments showed the expected dependence on protein concentration and incubation time (data not shown). By using data from several experiments similar to that shown in Fig. 7, the maximum velocity of the reaction using AIRs as a substrate was estimated to be 137.7 nmol of AIR formed/min/mg of protein. The presumed lack of AIRs in the natural environment prompted us to assay other potential in vivo substrates for this kinase, based on structural similarities. When the purine nucleosides adenosine, inosine, and guanosine were tested as substrates in concentrations similar to that used with AIRs, no phosphorylation was detected. Additionally, AICARs was not a substrate for STM4066. AICARs, like AIRs, is the nucleoside of a purine intermediate and must be phosphorylated prior to incorporation into the pathway. Further, the pyrimidine nucleosides cytosine, thymidine, and uridine and the pyridine nicotinamide riboside did not serve as a substrate for STM4066.

FIG. 7.

Purified STM4066 has AIRs kinase activity. AIRs kinase reactions were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, [32P]ATP alone; lane 2, no AIRs; lane 3, complete reaction; lane 4, boiled protein; lane 5, no protein.

Probing conditions to induce operon.

Insight about the role of proteins in vivo can sometimes be provided by identifying conditions that induce the respective genes. Because the transcriptional fusion that we had was in a permease that might be required for the inducing compound to enter the cell, Western analyses were used to address regulation. Strain DM5999 was grown in nutrient broth with the addition of ribose, fructose, glucose, and xylose (these sugars were added to a final concentration of 20 mM); AIRs (1 mM); and NAD (1 mM). None of these medium conditions resulted in a detectable accumulation of STM4066 protein.

DISCUSSION

The work described here was initiated to define the genetic lesion that allowed mutants blocked in de novo purine biosynthesis to efficiently use AIRs as a source of thiamine. This mutation was of interest since it provided a means to isolate the AIR to HMP branch of thiamine synthesis for analysis in vivo. Such isolation is critical for the in vivo studies to identify processes that specifically (but indirectly) affect the efficiency of this branch of thiamine synthesis.

Previous work suggested that utilization of AIRs in vivo would be limited by transport and/or the phosphorylation that is required for this metabolite to enter the purine and thiamine synthesis pathways as a ribotide intermediate. Herein we show that the overexpression of a single Salmonella-specific ORF, the STM4066 ORF, is sufficient to allow pur mutants to use ∼100-fold-less exogenous AIRs to satisfy a thiamine requirement than the parent strain. When purified, the STM4066 protein was shown to have AIRs kinase activity, consistent with the requirement that this intermediate enter the thiamine pathway as the ribotide form. The spontaneous mutant analyzed here contained a lesion in the negative regulator of the operon containing stm4066, which resulted in a >100-fold induction of transcription of these genes. Thus the causative mutation acts indirectly to cause the phenotype by altering the expression of the relevant kinase gene.

The mechanism of AIRs transport in Salmonella is not known. A reasonable candidate was the permease (STM4065) found in the operon with the kinase. However, nutritional experiments determined that the function of this permease was not needed for the utilization of AIRs allowed by overexpression of STM4066. It is likely that one of the general systems for nucleosides is a system for transporting AIRs. Thus, it is possible that mutations in the relevant transport system could further reduce the concentration of AIRs needed to satisfy an HMP requirement. Interestingly, we have no evidence for the conversion of the exogenously provided AIRs to purine products. Since the ribotide product is reported to be used in both pathways, we suggest that the amount of ribotide generated is still below the amount needed to make a significant impact on the purine requirement of the cell. The fact that the AIR generated is utilized for thiamine synthesis is consistent with other data suggesting that the branch point is biased toward thiamine synthesis at low levels of flux (1). The description by Newell and Tucker of strains that can utilize AIRs for both purine and thiamine suggests that an additional mutation(s) to increase the incorporation of the exogenous AIRs and allow a purine requirement to be satisfied could be identified (21).

Though a substrate for phosphorylation by STM4066 was identified by this work, the in vivo function of this protein and the others encoded by the operon remains unclear. It is unlikely that the cell has designed a system that scavenges AIRs, since significant concentrations of this metabolite are not expected to be present in the natural environment of Salmonella. It is possible that this operon provides the cell with the means to utilize an uncommon sugar(s) found in the natural environment of Salmonella. This possibility might justify the presence of this operon in Salmonella when it is lacking in E. coli. A role for each of the genes in such a scenario could be envisioned based on the functional predictions made by sequence analyses. For instance, a nucleotide sugar could be hydrolyzed by STM4067 to give a sugar that could be transported into the cell by STM4065, where it could be phosphorylated by STM4066 to enter into catabolism.

In the course of this work, the genetically defined pnuE locus (22) was found to be allelic to the ushB gene, immediately upstream of the stm4065-4068 locus of interest (data not shown). This result indicated that the NAD pyrophosphatase and UDP-sugar hydrolase activities are encoded by the same gene. The gene product has two demonstrated activities, NAD pyrophosphatase (14, 22) and UDP-sugar hydrolase (15). Furthermore, the ushB homolog in E. coli has an additional activity, attributed to genetic locus cdh, which encodes CDP-diglyceride hydrolase (6, 18). It is not clear which, if any, of these activities are physiologically relevant.

The work described here has validated the annotation of STM4066 and STM4068 as a kinase and regulator, respectively. In addition, this work has expanded our ability to probe cellular processes that affect the AIR-to-HMP-PP part of the thiamine biosynthetic pathway specifically. In the past, mutations (or conditions) affecting the common steps in the purine and thiamine pathways, PurF-independent phosphoribosylamine formation, or the conversion of AIR to HMP-PP would have resulted in similar phenotypes. Furthermore, identification of a protein able to phosphorylate AIRs provides a means to generate isotopically labeled AIR for in vitro studies probing the function of ThiC and other components involved in the conversion of AIR to HMP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by competitive grant GM47296 from the NIH. Funds were also provided from a 21st Century Scientist Scholars Award from the J. S. McDonnell Foundation. Michael Dougherty was supported by a Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation Annual Fellowship and a Biotechnology Traineeship from the NIH (T32 GM08349).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, S., J. L. Zilles, and D. M. Downs. 2002. Metabolic flux in both the purine mononucleotide and histidine biosynthetic pathways can influence synthesis of the hydroxymethyl pyrimidine moiety of thiamine in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 184:6130-6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck, B. J., and D. M. Downs. 1998. The apbE gene encodes a lipoprotein involved in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180:885-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begley, T. P., D. M. Downs, S. E. Ealick, F. W. McLafferty, A. P. Van Loon, S. Taylor, N. Campobasso, H. J. Chiu, C. Kinsland, J. J. Reddick, and J. Xi. 1999. Thiamin biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Arch. Microbiol. 171:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat, B., M. P. Groziak, and N. J. Leonard. 1990. Nonenzymatic synthesis and properties of 5-aminoimidazole ribonucleotide (AIR). Synthesis of specifically 15N-labeled 5-aminoimidazole ribonucleoside (AIRs) derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112:4891-4897. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulawa, C. E., and C. R. Raetz. 1984. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli strains defective in CDP-diglyceride hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 259:11257-11264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caetano-Annoles, G. 1993. Amplifying DNA with arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. PCR Methods Appl. 3:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castilho, B. A., P. Olfson, and M. J. Casadaban. 1984. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-Mu bacteriophage transposons. J. Bacteriol. 158:488-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, J. R. Roth, and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 10.Downs, D. M., and L. Petersen. 1994. apbA, a new genetic locus involved in thiamine biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:4858-4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escalante-Semerena, J. C., and J. R. Roth. 1987. Regulation of cobalamin biosynthetic operons in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 169:2251-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estramareix, B., and S. David. 1996. Biosynthesis of thiamine. New J. Chem. 20:607-629. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falconer, D. F., M. P. Spector, and J. W. Foster. 1984. Membrane association of NAD pyrophosphatase in Salmonella typhimurium. Curr Microbiol. 10:237-242. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster, J. W. 1981. Pyridine nucleotide cycle of Salmonella typhimurium: in vitro demonstration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide glycohydrolase, nicotinamide mononucleotide glycohydrolase, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide pyrophosphatase activities. J. Bacteriol. 145:1002-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett, A. R., L. A. Johnson, and I. R. Beacham. 1989. Isolation, molecular characterization and expression of the ushB gene of Salmonella typhimurium which encodes a membrane-bound UDP-sugar hydrolase. Mol. Microbiol. 3:177-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 17.Heard, J. T., Jr. 1983. Thin-layer chromatographic separation of intermediates of the pyridine nucleotide cycle. Anal. Biochem. 130:185-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Icho, T., C. E. Bulawa, and C. R. Raetz. 1985. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the gene for CDP-diglyceride hydrolase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 260:12092-12098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleckner, N., J. Roth, and D. Botstein. 1977. Genetic engineering in vivo using translocatable drug-resistance elements. New methods in bacterial genetics. J. Mol. Biol. 116:125-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Newell, P. C., and R. G. Tucker. 1968. Biosynthesis of the pyrimidine moiety of thiamine. A new route of pyrimidine biosynthesis involving purine intermediates. Biochem. J. 106:279-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park, U. E., J. R. Roth, and B. M. Olivera. 1988. Salmonella typhimurium mutants lacking NAD pyrophosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 170:3725-3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen, L., and D. M. Downs. 1996. Mutations in apbC (mrp) prevent function of the alternative pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:5676-5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen, L., J. Enos-Berlage, and D. M. Downs. 1996. Genetic analysis of metabolic crosstalk and its impact on thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics 143:37-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmieger, H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 119:75-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Way, J. C., M. A. Davis, D. Morisato, D. E. Roberts, and N. Kleckner. 1984. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene 32:369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb, E., K. Claas, and D. Downs. 1998. thiBPQ encodes an ABC transporter required for transport of thiamine and thiamine pyrophosphate in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8946-8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]