Abstract

OmpR and PhoB are response regulators that contain an N-terminal phosphorylation domain and a C-terminal DNA binding effector domain connected by a flexible interdomain linker. Phosphorylation of the N terminus results in an increase in affinity for specific DNA and the subsequent regulation of gene expression. Despite their sequence and structural similarity, OmpR and PhoB employ different mechanisms to regulate their effector domains. Phosphorylation of OmpR in the N terminus stimulates the DNA binding affinity of the C terminus, whereas phosphorylation of the PhoB N terminus relieves inhibition of the C terminus, enabling it to bind to DNA. Chimeras between OmpR and PhoB containing either interdomain linker were constructed to explore the basis of the differences in their activation mechanisms. Our results indicate that effector domain regulation by either N terminus requires its cognate interdomain linker. In addition, our findings suggest that the isolated C terminus of OmpR is not sufficient for a productive interaction with RNA polymerase.

Escherichia coli contains 28 histidine kinases and 32 response regulators (43) that couple changes in the environment to changes in gene expression or protein function (for a review, see reference 56). In their simplest form, two-component systems are comprised of a sensor kinase and a response regulator. The sensor kinase, typically a membrane-bound protein, responds to specific environmental signals by modulating its ability to phosphorylate (and in some cases dephosphorylate) its cognate response regulator. Response regulators are usually DNA binding proteins containing two domains separated by a flexible linker. The N-terminal receiver domain modulates the activity of the C-terminal effector domain. Most often, phosphorylation of the N terminus enhances the affinity of its C terminus for specific DNA, resulting in a subsequent change in gene expression.

In E. coli and related enteric bacteria, EnvZ is a membrane-bound histidine kinase (12) that undergoes autophosphorylation by intracellular ATP (EnvZ-P) (1, 13, 20). EnvZ-P transfers the phosphate to its cognate response regulator, OmpR (1, 2, 13, 21, 22). OmpR reciprocally regulates transcription of the outer membrane porin genes ompF and ompC in response to changes in medium osmolarity (14, 18, 32, 47, 53, 54). OmpF is the predominant porin at low osmolarity, whereas OmpC predominates at high osmolarity (4). PhoB is a response regulator in the same subfamily and is highly homologous to OmpR. Under conditions of limiting inorganic phosphate, PhoB activates the transcription of a regulon involved in the metabolism and uptake of phosphorus-containing compounds (33, 51, 63, 64; for a review, see reference 65). Phosphorylation by the inner-membrane-bound histidine kinase PhoR controls the levels of phosphorylated PhoB in response to extracellular inorganic phosphate levels (34, 37, 66).

Response regulators share a conserved, doubly wound α/β fold and phosphorylation site geometry in their N terminus but are grouped into subfamilies based on the structure of their C-terminal domains (31, 55, 62). OmpR and PhoB are members of the winged-helix-turn-helix family of DNA binding proteins (6; for reviews, see references 23, 26, and 38). The major differences between OmpR and PhoB reside in the interdomain linker (15 residues versus 6 residues, respectively) and in the transactivation loop that precedes the DNA recognition helix (45). Apart from these differences, the C-terminal structures of OmpR (39) and PhoB (45) are readily superimposed (23). Despite their significant structural homology, OmpR and PhoB employ different mechanisms to regulate their DNA binding domains and activate transcription. Phosphorylation of OmpR enhances its affinity for specific DNA (2, 16, 17), and substitution of aspartate 55, the site of phosphorylation (10), with glutamine (24) or alanine (V. K. Tran and L. J. Kenney, unpublished data) renders OmpR unable to activate transcription. The isolated C terminus of OmpR (OmpRC) binds to DNA only weakly (25, 57) and is unable to activate transcription (reference 60 and this work). These findings indicate that OmpRC requires its phosphorylated N-terminal domain for activation and suggest that the N terminus of OmpR (OmpRN) may be required for proper interactions with RNA polymerase (RNAP). In contrast, the isolated C terminus of PhoB (PhoBC) is constitutively active for transcription (36) and has a higher affinity for specific DNA than full-length, unphosphorylated PhoB (11). The unphosphorylated N terminus of PhoB (PhoBN) inhibits its DNA binding domain, and genetic evidence suggests that the α5 helix of the N terminus is responsible for the inhibition of PhoBC (3). In summary, phosphorylation of OmpR enhances DNA binding affinity whereas phosphorylation of PhoB results in a relief of the inhibition of DNA binding.

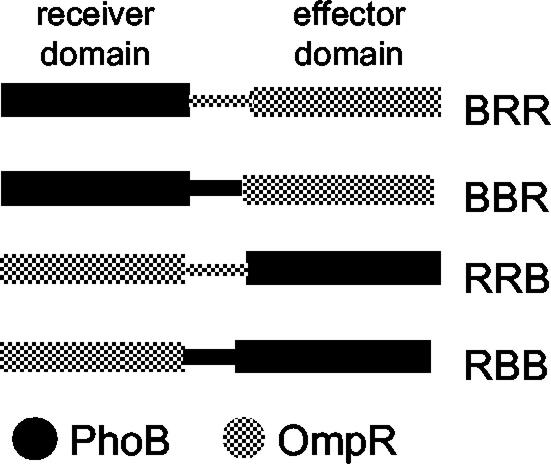

We are interested in the structural basis of the differences with which the highly homologous response regulators OmpR and PhoB regulate their DNA binding domains. Evidence from our laboratory indicates that the OmpR interdomain linker is important for signaling to the C terminus (5, 27, 41). To better understand the functions of the N-terminal domain and interdomain linker in effector domain regulation, we constructed chimeras between OmpR and PhoB that contained either interdomain linker (Fig. 1). In the present work, we emphasize the distinct role of the interdomain linker in the communication between the N terminus and C terminus of response regulators. From the results presented here, it is apparent that structural homology does not always infer functional homology, even among closely related members of the same response regulator subfamily.

FIG. 1.

Structures of the OmpR-PhoB chimeras. The PhoB N terminus, linker, and C terminus are depicted in black. The OmpR domains are shown in grey. The three-letter chimera designations, from left to right, refer to the sources of the N terminus, linker, and C terminus, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of OmpR-PhoB chimeras.

The ompR and phoB genes were subcloned into a Bluescript KS vector (Novagen) by using the XbaI and HindIII restriction sites to create templates for subsequent constructions (pOmpR and pPhoB, respectively). The following oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1. Silent SalI sites were engineered at the 5′ end of the ompR and phoB linkers by site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides OmpR-S and PhoB-S to create pOmpR-Sal and pPhoB-Sal, respectively, following a method described previously (58). XhoI sites were engineered at the 3′ end of the ompR and phoB linkers by using oligonucleotides OmpR-X and PhoB-X to create pOmpR-Xho and pPhoB-Xho, respectively. Domain swapping was carried out by cutting recipient and donor plasmids with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligating the relevant fragments with T4 DNA ligase. For example, the BBR chimera was constructed by replacing the XhoI-HindIII fragment of pPhoB-Xho with that from pOmpR-Xho. The remaining chimeric genes were constructed in a similar manner. The XhoI sites were removed from the BBR and RRB chimeric genes by using oligonucleotides BBR and RRB, respectively. For the alkaline phosphatase assays, the RBB and RRB chimeras were PCR amplified with primers OmpR5 and PhoB3 and subcloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of the arabinose-inducible expression vector pMPM-A6 (42) to create plasmids pARA-RBB and pARA-RRB, respectively. E. coli strain DH5α was used for cloning. Standard cloning techniques were described previously (50). Restriction enzymes were obtained from Life Technologies, T4 DNA ligase was obtained from Roche, and Pfu polymerase was purchased from Stratagene. The correct DNA sequence of the final construct was confirmed by automatic sequencing done by the Molecular Microbiology & Immunology Core Facility at Oregon Health & Science University.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in plasmid constructionsb

| Oligo- nucleotide | Sequence from 5′ to 3′a |

|---|---|

| OmoR-S | GCGGTGCTGCGTCGACAGGCGAAGGAACTGC |

| PhoB-S | GCGGTAATGCGTCGACTTTCGCCAATGGCG |

| OmpR-X | CCGTCACAGGAAGAGGCGCTCGAGGCTTTCGGTAAGTTC |

| PhoB-X | CCAATGGCGGTGGAAGAGCTCGAGGAGATGCAGGG |

| BBR | CCAATGGCGGTGGAAGAGGTCATTGCATTCGGTAAGTTC |

| BRR | CCGTCACAGGAAGAGGCGGTAATTGCTTTCGGTAAGT |

| OmpR5 | GAATTCACCATGCAAGAGAACTACAAGATTCTG |

| PhoB3 | CTGCAGAAGCTTTTAAAAGCGGGTTGAAAAACGA |

Only top-strand sequences are shown.

Engineered restriction sites are underlined.

Expression and purification of the response regulators.

The ompR-phoB chimeras and wild-type phoB were subcloned into pET22b (Novagen) by using the XbaI and HindIII restriction sites. E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was used for protein expression. One liter of cells in Luria-Bertani medium was grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.6 before induction with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were harvested 3 h after induction. The cell pellet was resuspended in TGED (25 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol) containing 1 mM AEBSF [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-sulfonyl fluoride; ICN Biomedicals]. After lysis with a French press (two passages at 10,000 lb/in2) and centrifugation for 1 h at 30,000 × g, the supernatant was dialyzed overnight in TGED before loading onto a Hi-Trap heparin column (Pharmacia). Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 500 mM NaCl. The desired fractions were combined. NaCl (2 M) was added to the pooled fractions before loading onto a phenyl-Sepharose column (Pharmacia) and eluted with a linear gradient of 2 to 0 M NaCl. Pooled fractions were judged to be >90% pure by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). OmpR and OmpRN proteins were purified as described by Kenney et al. (27) with the modifications detailed in reference 16.

DNA binding.

Fluorescence anisotropy was used to measure equilibrium binding, and the experiments were performed as previously described (16). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used were the same as those used in the previous study. The results from the binding curves were fit by nonlinear least-squares regression as described (16). The apparent dissociation constants from the individual binding curves are reported in Table 2. The values shown in Table 2 represent the mean ± the standard deviation.

TABLE 2.

Summary of DNA binding measurements

| Oligonucleotidea |

Kd (nM) ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BRR | BBR | |

| F1 | 108 ± 32 | NSBb |

| F123 | 133 ± 13 | NSB |

| C1 | 73 ± 39 | 295 ± 52 |

| C123 | NSB | NSB |

Neither chimera bound to the low-affinity sites F2, F3, C2, and C3 (data not shown).

NSB, nonsaturable binding.

EnvZ115 and PhoR purification and phosphorylation.

EnvZ115 was expressed and purified as previously described (20), and the kinase assay was conducted as described previously (28, 59). Thioredoxin-tagged PhoR was a gift from William McCleary, and the kinase assays were performed as for EnvZ. Modifications to the kinase assay are listed in the figure legends.

β-Galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase assays.

Wild-type ompR, BRR, and BBR were subcloned into pFR29*, an envZ null derivative of plasmid pFR29 (48). The plasmid was used to transform the ompR deletion strains MH513.101 and MH225.101, which contain chromosomal copies of the ompF-lacZ and ompC-lacZ fusions, respectively (15). β-Galactosidase assays were carried out according to the method of Tran et al. (58). β-Galactosidase activity was expressed in Miller units and calculated by using the formula 1,000 × OD420/(time [min] × culture volume [ml] × OD600).

Plasmids pARA-BBR and pARA-BRR were transformed into strain BW25113 or BW28669 (Barry Wanner, Purdue University) for the phoA assays. BW28669 is an envZ mutant derivative of BW25113 constructed by following a method described previously (9). Alkaline phosphatase assays were performed as follows. Transformants were grown to mid to late log phase, and OD readings were obtained by using a Molecular Devices UVmax microtiter plate reader. A 1-ml volume of cells was resuspended in 1 ml of 1 M Tris (pH 8.2) and lysed with SDS and chloroform, and debris was removed by brief centrifugation. Assays were carried out on microtiter plates with 200 μl of cell extract and 20 μl of 4 mM o-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma). After 15 min at 37°C, 80 μl of 1 M KH2PO4 was added to each reaction mixture before obtaining OD405 readings. Alkaline phosphatase activity (arbitrary units) was expressed as 100 × OD405/OD570.

RESULTS

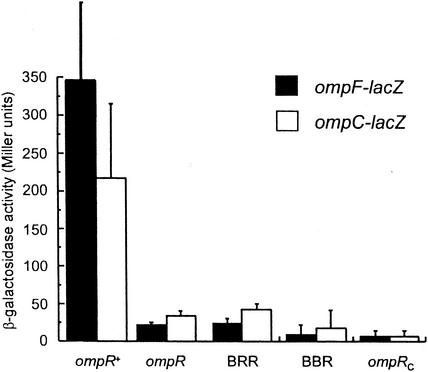

PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras (BRR and BBR) are unable to activate transcription of OmpR-dependent genes.

We were interested in whether or not chimeras containing the OmpR DNA binding domain were able to activate the transcription of ompF or ompC (BBR and BRR [Fig. 1 ]). The chimeras were expressed in multicopy in ompR null strains containing chromosomal copies of ompF-lacZ or ompC-lacZ operon fusions (15). The results of the β-galactosidase assays are depicted in Fig. 2. In rich media, the strains containing a chromosomal copy of ompR expressed both ompF and ompC while transcription of either porin gene was not observed in the ompR mutant strains (Fig. 2). When the chimeras (BRR and BBR) were expressed in the ompR null reporter strains, neither was able to activate transcription of ompF or ompC (Fig. 2). These results indicate that both chimeras are defective in activating the transcription of OmpR-dependent genes. We also tested whether or not OmpRC activated the transcription of single-copy reporter fusions. Overexpression of OmpRC did not result in the activation of either ompF or ompC, indicating that OmpR requires its N terminus for transcriptional activation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional activation by the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Activities of the ompF-lacZ strain MH513.101 and the ompC-lacZ strain MH225.101 are shown. The ompR+ strains are derivatives of MH225.101 and MH513.101 that contain a chromosomal copy of ompR. At least two independent assays were performed on each strain; the error bars indicate +1 standard deviation. ompR, ompR null.

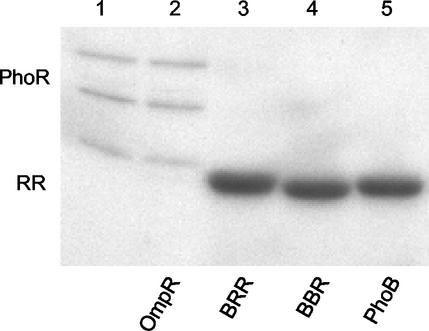

PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras (BRR and BBR) are phosphorylated by PhoR.

One explanation for the inability of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras to activate the transcription of OmpR-dependent genes is that they may not be phosphorylated by PhoR, the cognate kinase for the PhoB N terminus. We used a kinase assay to examine the phosphotransfer between PhoR and the chimeras (Fig. 3). Preincubation of PhoR with [γ-32P]ATP resulted in autophosphorylation (PhoR-P), as shown in lane 1 of Fig. 3. During expression and/or purification of this preparation, PhoR underwent proteolysis, as evident from the three bands of varying size corresponding to phosphoprotein (William McCleary, personal communication). To examine kinase specificity, PhoR-P was mixed with the noncognate response regulator OmpR. No evidence of phosphotransfer between PhoR and OmpR was indicated (Fig. 3, lane 2). We also tested a higher ratio of PhoR to OmpR (1:1) and did not observe phosphotransfer (data not shown). In contrast, when PhoB or either chimera containing PhoBN was incubated with PhoR-P, phosphotransfer occurred (Fig. 3, lanes 3 through 5). The results shown in Fig. 3 also demonstrate that phosphotransfer between PhoR and the chimeras occurs with an efficiency similar to that for the phosphotransfer between PhoR and PhoB, suggesting that the presence of a heterologous C terminus does not affect the phosphorylation of PhoBN when PhoR-P is the phosphodonor. Thus, the lack of transcriptional activation observed in Fig. 2 is not due to an inability of the chimeras to be phosphorylated.

FIG. 3.

Phosphorylation of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras by PhoR. The kinase assay is described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1 contains 2 μg of thioredoxin-tagged PhoR that has been autophosphorylated by [γ-32P]ATP; the three bands correspond to the proteolytic cleavage products of PhoR. The response regulator (RR; 5.5 μg) in each reaction is indicated by the labels under the gel. The reactions were carried out for 30 min at 37°C and stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

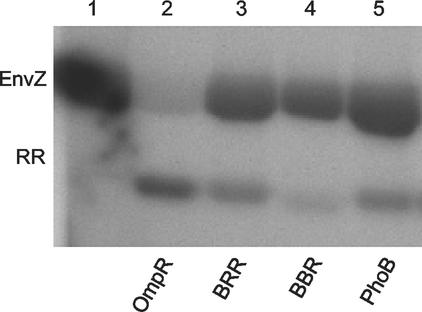

PhoB and PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras (BRR and BBR) are phosphorylated by the noncognate kinase EnvZ.

Although it would not be expected that OmpRC would bind to PhoB-specific DNA, it has been suggested that cross talk occurs at the kinase level (59, 61) (see Discussion). As a result, we examined whether or not wild-type PhoB could be phosphorylated by EnvZ. Lane 1 of Fig. 4 demonstrates that EnvZ underwent autophosphorylation in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (EnvZ-P). When EnvZ-P was mixed with its cognate response regulator, OmpR, phosphotransfer was observed (Fig. 4, lane 2). When PhoB was incubated with EnvZ-P, phosphotransfer was also seen, but to a lesser extent than that with OmpR (Fig. 4, compare lanes 2 and 5). However, the reverse reaction, i.e., phosphorylation of OmpR by the noncognate kinase PhoR, does not appear to have occurred in vitro (Fig. 3, lane 2). Thus, it appears that cross talk is not bidirectional, since EnvZ phosphorylates PhoB (Fig. 4, lane 5), but PhoR does not appear to phosphorylate OmpR in vitro (Fig. 3, lane 2) or requires higher concentrations of PhoR.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylation of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras by EnvZ. The kinase assay is described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1 contains 35 μg of EnvZ that has been autophosphorylated by [γ-32P]ATP. The response regulator in each reaction (RR; 5.5 μg) is indicated by the labels under the gel. The reactions were carried out for 30 min at 37°C and stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

We also tested the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras to determine if they were phosphorylated by the noncognate kinase EnvZ. When BRR was included in a kinase assay with EnvZ-P, phosphotransfer occurred to a level similar to that observed with wild-type PhoB (Fig. 4, compare lanes 3 and 5). This result further demonstrates that the transcriptional activation defect of BBR and BRR is not due to a defect in phosphorylation. Not surprisingly, phosphorylation of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras by EnvZ is less efficient than is phosphorylation by PhoR. Interestingly, BBR, containing the PhoB linker, is phosphorylated less efficiently by the noncognate kinase EnvZ than is wild-type PhoB or BRR (Fig. 4, lane 4). Perhaps the shorter interdomain linker in BBR positions PhoBN in a manner that alters the phosphorylation site, making it less accessible.

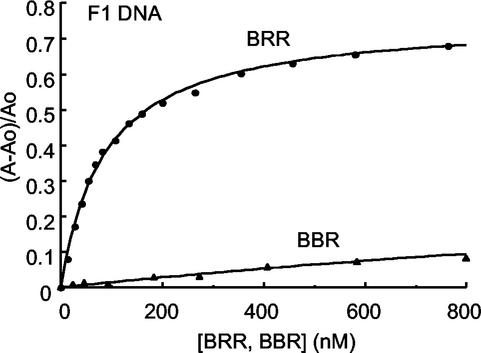

The linker affects the DNA binding properties of OmpRC.

We next examined the DNA binding properties of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras to determine the basis for their defects in transcriptional activation (Fig. 2). Protein-DNA interactions were quantified by fluorescence anisotropy as previously described (16). A representative DNA binding curve is shown in Fig. 5. BRR, containing the OmpR linker, exhibits saturable binding to the high-affinity site F1 (average Kd = 108 nM). In contrast, in the presence of BBR, containing the PhoB linker, no saturable binding was observed. The results of our binding assays are summarized in Table 2. The chimera containing the OmpR linker (BRR) binds to ompF DNA with high affinity. In addition, when it binds to the isolated site, C1, the Kd is 73 nM. Interestingly, BRR does not bind to the composite ompC site C123. Binding at C1, but not C123, has been observed previously (40) (see Discussion). BBR is unable to bind to ompF DNA and only weakly binds to the highest affinity site C1 (Kd = 295 nM). The results from our binding assays indicate that the source of the interdomain linker governs the DNA binding properties of OmpRC. When the PhoB N terminus is linked to OmpRC via the PhoB linker (BBR), DNA binding is prevented. In contrast, the PhoB N terminus is unable to inhibit the DNA binding of OmpRC at ompF when the OmpR linker (BRR) is present. Thus, PhoBN requires its cognate interdomain linker to inhibit the heterologous OmpR C terminus.

FIG. 5.

DNA binding of BRR and BBR to the F1 binding site. BRR (circles) or BBR (triangles) was titrated into the binding reaction in the presence of 3 nM fluorescein-labeled F1 oligonucleotide. The means from five separate measurements performed at each titration point were plotted. The curve illustrates the change in anisotropy (A), where (A−Ao)/Ao represents the difference in anisotropy in the presence of protein minus the anisotropy in the absence of protein divided by the anisotropy in the absence of protein. This value is plotted as a function of the total protein concentration.

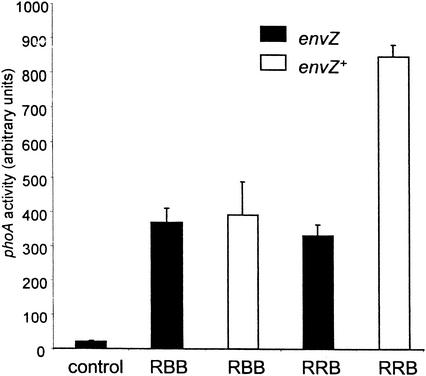

OmpRN-PhoBC (RRB and RBB) chimeras activate transcription of phoA.

The inverse chimeras containing the OmpR N terminus and the PhoB C terminus were constructed to determine how PhoBC behaves when linked to OmpRN via either interdomain linker (RBB and RRB [Fig. 1]). We examined their ability to activate the transcription of a chromosomal copy of the PhoB-specific reporter gene phoA. The chimeric genes were expressed in multicopy in isogenic envZ+ and envZ null backgrounds. The strain containing RRB exhibited a low level of basal phoA activity in the absence of induction (Fig. 6, control). In the absence of the envZ kinase gene, the chimeras activated the transcription of phoA to similar levels (Fig. 6, black bars). Thus, neither OmpRN-PhoBC chimera (RRB nor RBB) requires EnvZ for activity. Because the chimeras were constitutively active in an envZ null background, the results also indicate that OmpRN, unlike PhoBN, cannot inhibit DNA binding by PhoBC. In an envZ+ background, RBB activated transcription to similar levels as in an envZ null background (RBB) (Fig. 6, white bar). Interestingly, the activity of RRB was increased almost threefold in an envZ+ background compared to that in an envZ mutant background (Fig. 6, compare white and black bars of RRB columns). Presumably, OmpRN is phosphorylated by EnvZ, resulting in the activation of PhoBC, whose activation requires the OmpR linker.

FIG. 6.

Transcriptional activation by the OmpRN-PhoBC chimeras. Alkaline phosphatase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The activities of strains BW25115 (envZ+) and BW28669 (envZ null [envZ]) are indicated by the solid and open bars, respectively; the error bars indicate +1 standard deviation. Assays were performed in triplicate on three independent colonies. The control strain was grown with plasmid pARA-RRB without arabinose induction. RBB and RRB refer to strains containing plasmids pARA-RBB and pARA-RRB, respectively.

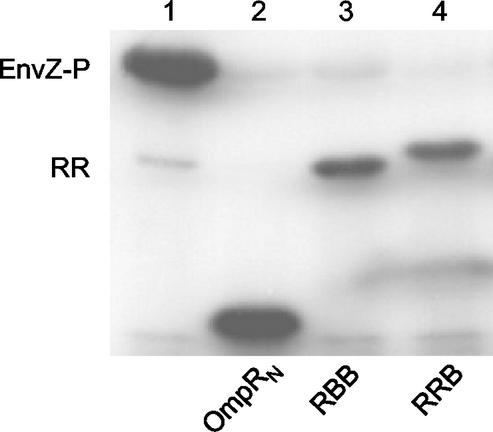

OmpRN-PhoBC chimeras (RRB and RBB) are phosphorylated by EnvZ.

Since RRB was activated by EnvZ in vivo whereas RBB was not (Fig. 6), it was of interest to determine whether EnvZ could phosphorylate the chimeras in vitro. EnvZ was preincubated with [γ-32P]ATP (Fig. 7, lane 1) and then mixed with the indicated response regulator. OmpRN was used as a positive control for phosphotransfer (Fig. 7, lane 2). As shown in Fig. 7, both chimeras were phosphorylated by EnvZ to similar levels in vitro (lanes 3 and 4). The observation that EnvZ can phosphorylate RRB accounts for the enhancement of transcription observed in the presence of the envZ gene (Fig. 6). However, it was surprising that the RBB chimera was also phosphorylated by EnvZ (Fig. 7, lane 4) yet the phosphorylation of RBB did not result in the activation of its PhoB C terminus. In isogenic envZ+ and envZ null strains, expression of RBB resulted in similar levels of phoA activity (Fig. 6). Because the chimeras differ only in the interdomain linker, the result shown in Fig. 7 further demonstrates that the presence of the OmpR linker activates PhoBC. An interesting observation was that a difference of approximately 600 Da between RBB and RRB resulted in a visible difference in mobility on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Phosphorylation of the OmpRN-PhoBC chimeras by EnvZ. The kinase assays are described in Materials and Methods. The phosphotransfer reaction was performed for 1 h at room temperature and stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Lane 1 contains 2 μg of EnvZ autophosphorylated by [γ-32P]ATP. The response regulator (RR; 0.3 μg) in each reaction is indicated by the labels under the gel.

DISCUSSION

OmpR requires its N terminus for transcriptional activation.

The PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras with either linker are unable to activate the transcription of ompF or ompC (Fig. 2). Apparently, PhoBN cannot function as a substitute for OmpRN in order to activate the transcription of OmpR-dependent genes. This requirement for OmpRN is further demonstrated by the inability of an isolated OmpRC fragment to activate transcription (reference 60 and this work) (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with the observation that PhoBN regulates its C terminus by an inhibitory mechanism, whereas OmpRN acts positively on its C terminus. OmpRN may be required to stabilize the OmpRC conformation competent for DNA binding and transcriptional activation. It is noteworthy that OmpR and PhoB interact with different subunits of RNAP holoenzyme in order to activate transcription. PhoB uses the loop between α helices 2 and 3 of its C terminus (i.e., the transactivation loop) to make contacts with σ70 of RNAP holoenzyme to activate transcription (19, 29, 35, 36). In contrast, OmpR interacts with the α subunit of RNAP to activate transcription (19, 49, 52). However, the evidence is less clear whether the transactivation loop of OmpR makes contacts with α to activate transcription or whether contacts outside of this region are required. For example, a screen for positive control mutants of OmpR identified residue R42 of the N terminus as being important for transcriptional activation, which is suggestive that the N terminus is important for interaction with RNAP (46). Evidence exists for an interaction with RNAP via the N terminus of another response regulator, Spo0A. A screen for suppressors of a Spo0F-null phenotype identified a mutation in the N terminus of Spo0A (P60S) that results in enhanced interaction with RNAP (8). The possibility that OmpRN is required for RNAP interactions would account for the inability of the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras to activate transcription at OmpR-dependent promoters.

OmpR requires its linker for activation of its C terminus.

The inverse chimeras containing the PhoB DNA binding domain (RBB and RRB) demonstrate a requirement for the OmpR interdomain linker to stimulate transcriptional activation by PhoBC. In an envZ+ background, RRB displays an enhanced ability to activate transcription, compared to that in an envZ null background (Fig. 6). Clearly, OmpRN can activate a heterologous effector domain. In contrast, in the presence of RBB, alkaline phosphatase activity was independent of EnvZ (Fig. 6). The results shown in Fig. 6 indicate that OmpRN activation of PhoBC is dependent on the OmpR linker. Because OmpRC and the PhoBN-OmpRC chimeras are unable to activate transcription (Fig. 2), our findings indicate that OmpRN and the OmpR linker are both required for the activation of OmpRC. In addition, OmpRN does not contain an inhibitory function, a finding that further distinguishes the activation mechanism of OmpR from PhoB.

One explanation for the lack of phosphorylation-induced activation of RBB is that it is not phosphorylated in vivo. However, direct measurements of phosphorylation by the kinase EnvZ (Fig. 7) demonstrate that RBB is phosphorylatable in vitro. Another, somewhat unlikely possibility is that the phosphorylated form of RBB could be unstable in vivo. Both RBB and RRB display similar phosphorylation properties, yet only RRB is activated by EnvZ in vivo. This observation makes a third possibility likely, that phosphorylation of the RBB chimera in vivo is without consequence. In other words, phosphorylation of the N terminus does not result in enhanced DNA binding by the C terminus. The linkers of PhoB and OmpR differ in both sequence and length. The shorter PhoB linker (6 residues versus 15 residues for OmpR) could alter the interdomain interface of RBB to disrupt signaling. Alternatively, the linkers of OmpR and PhoB could have different roles in signaling phosphorylation-dependent changes in the N terminus to the C terminus.

The OmpR linker is required for DNA binding by OmpRC.

Although BBR and BRR did not activate transcription, DNA binding measurements revealed that their binding properties depend on the source of the interdomain linker. BRR was able to bind to DNA, whereas BBR containing the PhoB linker was not (Fig. 5; Table 2). BRR bound to ompF DNA with high affinity and was able to bind to an isolated ompC site (C1) but not to a composite site (C123 [Table 2]). This binding behavior resembles that of the OmpR mutant T83I (40). The observation that T83I binds to ompF but not to ompC composite sites led to the conclusion that the substitution locks OmpR in a low-osmolarity conformation that can bind to ompF sites (F123) and the high-affinity ompC site C1. The BRR binding data indicate that it is also locked in this low-osmolarity conformation, which prevents binding at ompC (i.e., PhoBN does not inhibit binding to ompC). BBR did not bind to ompF or ompC DNA (Table 2). One explanation for this result is that PhoBN inhibits DNA binding by OmpRC, but only when the PhoB interdomain linker is present. In a previous report, an internal deletion of the PhoB linker resulted in constitutive phoA transcription, suggesting that the linker, in addition to the α5 helix, is required for PhoBC inhibition (3). Our DNA binding results with the chimera containing the PhoB interdomain (BBR) linker could be interpreted as a requirement for the PhoB linker in effector domain inhibition.

OmpR linker length is important for effector domain regulation.

Our results with OmpR and PhoB chimeras demonstrate a role for the interdomain linker and raise the question of which feature of the linker is important for signaling, its length or specific amino acid sequence? This question was directly addressed in a separate study in which linker substitutions (in particular, a polyQ derivative) were used to examine the role of linker length on function. While specific amino acid substitutions resulted in an ompF(Con) ompC null phenotype, changing the linker length had more profound effects on signaling. Increasing the linker length to 20 amino acids (Q20) decreased the level of ompF activation compared to that in the wild type, and its expression was constitutive. Conversely, with a Q10 linker, there was barely any activation of ompF and, at shorter linker lengths, ompF or ompC was not expressed (41).

Determinants of kinase specificity differ between OmpR and PhoB.

Interestingly, we found that EnvZ phosphorylates PhoB yet PhoR does not appear to phosphorylate OmpR in vitro under the conditions tested (Fig. 3 and 4). The in vivo relevance of this unidirectional cross talk is not known, but our data suggest that the determinants of kinase specificity differ between OmpR and PhoB. Our results agree with previous reports suggesting a role for noncognate kinases in the regulation of PhoB-dependent genes under certain conditions. In phoR creC ompR-null mutants, envZ is required for the activation of PhoB (30). However, this process also requires the genes for acetyl phosphate synthesis (ackA and pta) and requires that OmpR, the cognate response regulator for EnvZ, be absent from the cell. OmpR is also subject to phosphorylation by noncognate histidine kinases. The gene for the hybrid kinase EvgA was isolated as a multicopy suppressor of an EnvZ-null phenotype with respect to ompC expression (61). Another report demonstrated that a C-terminal fragment of the hybrid kinase ArcB weakly phosphorylates OmpR in vitro (i.e., compared to phosphorylation of the cognate response regulator ArcA [59]). Thus, noncognate histidine kinases may phosphorylate OmpR and PhoB in vivo. However, between the EnvZ/OmpR and PhoR/PhoB two-component systems, cross talk appears to be unidirectional.

Is there a role for the α5 helix in OmpR signaling?

Because the PhoB α5 helix is involved in signaling (3) and the OmpR α5 helix is highly homologous to that of PhoB (70% identical), it would seem likely that the α5 helix of OmpR has a role in signaling to the C terminus. This prediction is supported by OmpR α5 helix mutants E111K and R115S, which are both defective at the transcriptional activation of ompF and ompC (7, 44). The R115S mutant binds to DNA with similar affinity as unphosphorylated OmpR, but phosphorylation does not stimulate DNA binding. These results suggest that R115S is a true signaling mutant and not simply a DNA binding mutant, in agreement with a role for the α5 helix in postphosphorylation signaling.

Characterization of CheY-PhoB chimeras and N-terminal truncation mutants of PhoB indicate that the α5 helix of PhoB inhibits its effector domain and that phosphorylation relieves this inhibition (3). Thus, we constructed a third OmpRN-PhoBC chimera containing the PhoB α5 helix and the PhoB linker to examine the behavior of the PhoB α5 helix when fused to OmpRN. In the isogenic envZ+ and envZ null strains, this chimera was able to activate the transcription of phoA, suggesting that it does not require phosphorylation by EnvZ for function (data not shown). It is apparent that the PhoB α5 helix behaves differently (i.e., it is unable to inhibit its C terminus) when fused to OmpRN than when present in PhoBN. This result further highlights the mechanistic differences with which OmpRN and PhoBN regulate their C termini. Presumably, the OmpR N terminus is unable to maintain the PhoB α5 helix in an inhibitory conformation, even in the absence of phosphorylation.

Conclusions.

OmpR and PhoB are among the most closely related response regulators of the OmpR subfamily of winged-helix-turn-helix proteins (23, 26), yet they use different mechanisms to regulate their DNA binding domains. Phosphorylation of OmpRN stimulates a basal activity of OmpRC that results in enhanced DNA binding and transcriptional activation. In contrast, phosphorylation of PhoBN relieves inhibition mediated by the α5 helix, which enables DNA binding and transcriptional activation by PhoBC. In OmpR and PhoB, effector domain regulation requires both the N terminus and an interdomain linker of proper length. Clearly, the different properties exhibited by OmpR and PhoB domains indicate that structural homology does not always imply functional homology.

Acknowledgments

We thank William McCleary (University of Utah) for a preparation of thioredoxin-tagged PhoR. Barry Wanner (Purdue University) kindly provided strain BW25115 and its envZ null derivative. We thank Xiuhong Feng, Jack Kaplan, Kirsten Mattison, and Ricardo Oropeza from OHSU for discussion of and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NSF grant MCB-9904658 (to L.J.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., T. Mizuno, and S. Mizushima. 1989. Transfer of phosphoryl group between two regulatory proteins involved in osmoregulatory expression of the ompF and ompC genes in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 264:8563-8567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba, H., F. Nakasai, S. Mizushima, and T. Mizuno. 1989. Phosphorylation of a bacterial activator protein, OmpR, by a protein kinase, EnvZ, results in stimulation of its DNA-binding ability. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 106:5-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, M. P., K. B. Zumbrennen, and W. R. McCleary. 2001. Genetic evidence that the α5 helix of the receiver domain of PhoB is involved in interdomain interactions. J. Bacteriol. 183:2204-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alphen, W. V., and B. Lugtenberg. 1977. Influence of osmolarity of the growth medium on the outer membrane protein pattern of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 131:623-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ames, S. K., N. Frankema, and L. J. Kenney. 1999. C-terminal DNA binding stimulates N-terminal phosphorylation of the outer membrane protein regulator OmpR from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11792-11797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan, R. G. 1993. The winged-helix DNA-binding motif: another helix-turn-helix takeoff. Cell 74:773-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brissette, R. E., K. Tsung, and M. Inouye. 1992. Mutations in a central highly conserved non-DNA-binding region of OmpR, an Escherichia coli transcriptional activator, influence its DNA-binding ability. J. Bacteriol. 174:4907-4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervin, M. A., and G. B. Spiegelman. 1999. The Spo0A sof mutations reveal regions of the regulatory domain that interact with a sensor kinase and RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 31:597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delgado, J., S. Forst, S. Harlocker, and M. Inouye. 1993. Identification of a phosphorylation site and functional analysis of conserved aspartic acid residues of OmpR, a transcriptional activator for ompF and ompC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 10:1037-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellison, D. W., and W. R. McCleary. 2000. The unphosphorylated receiver domain of PhoB silences the activity of its output domain. J. Bacteriol. 182:6592-6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forst, S., D. Comeau, S. Norioka, and M. Inouye. 1987. Localization and membrane topology of EnvZ, a protein involved in osmoregulation of OmpF and OmpC in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 262:16433-16438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forst, S., J. Delgado, and M. Inouye. 1989. Phosphorylation of OmpR by the osmosensor EnvZ modulates expression of the ompF and ompC genes in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:6052-6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forst, S. A., J. Delgado, and M. Inouye. 1989. DNA-binding properties of the transcription activator (OmpR) for the upstream sequences of ompF in Escherichia coli are altered by envZ mutations and medium osmolarity. J. Bacteriol. 171:2949-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, M. N., and T. J. Silhavy. 1981. Genetic analysis of the ompB locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Mol. Biol. 151:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Head, C. G., A. Tardy, and L. J. Kenney. 1998. Relative binding affinities of OmpR and OmpR-phosphate at the ompF and ompC regulatory sites. J. Mol. Biol. 281:857-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, K. J., and M. M. Igo. 1996. Identification of the bases in the ompF regulatory region, which interact with the transcription factor OmpR. J. Mol. Biol. 262:615-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, K. J., J. L. Schieberl, and M. M. Igo. 1994. A distant upstream site involved in the negative regulation of the Escherichia coli ompF gene. J. Bacteriol. 176:1309-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igarashi, K., A. Hanamura, K. Makino, H. Aiba, T. Mizuno, A. Nakata, and A. Ishihama. 1991. Functional map of the α subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: two modes of transcription activation by positive factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8958-8962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igo, M. M., and T. J. Silhavy. 1988. EnvZ, a transmembrane environmental sensor of Escherichia coli K-12, is phosphorylated in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 170:5971-5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igo, M. M., A. J. Ninfa, J. B. Stock, and T. J. Silhavy. 1989. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of a bacterial transcriptional activator by a transmembrane receptor. Genes Dev. 3:1725-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igo, M. M., A. J. Ninfa, and T. J. Silhavy. 1989. A bacterial environmental sensor that functions as a protein kinase and stimulates transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 3:598-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itou, H., and I. Tanaka. 2001. The OmpR-family of proteins: insight into the tertiary structure and functions of two-component regulator proteins. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 129:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanamaru, K., H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 1990. Transmembrane signal transduction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli: I. Analysis by site-directed mutagenesis of the amino acid residues involved in phosphotransfer between the two regulatory components, EnvZ and OmpR. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 108:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato, M., H. Aiba, S. Tate, Y. Nishimura, and T. Mizuno. 1989. Location of phosphorylation site and DNA-binding site of a positive regulator, OmpR, involved in activation of the osmoregulatory genes of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 249:168-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenney, L. J. 2002. Structure/function relationships in OmpR and other winged-helix transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenney, L. J., M. D. Bauer, and T. J. Silhavy. 1995. Phosphorylation-dependent conformational changes in OmpR, an osmoregulatory DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8866-8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenney, L. J. 1997. Kinase activity of EnvZ, an osmoregulatory signal transducing protein of Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 346:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, S. K., K. Makino, M. Amemura, A. Nakata, and H. Shinagawa. 1995. Mutational analysis of the role of the first helix of region 4.2 of the σ70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation by activator protein PhoB. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim, S. K., M. R. Wilmes-Riesenberg, and B. L. Wanner. 1996. Involvement of the sensor kinase EnvZ in the in vivo activation of the response-regulator PhoB by acetyl phosphate. Mol. Microbiol. 22:135-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukat, G. S., B. H. Lee, J. M. Mottonen, A. M. Stock, and J. B. Stock. 1991. Roles of the highly conserved aspartate and lysine residues in the response regulator of bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8348-8354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda, S., and T. Mizuno. 1990. Evidence for multiple OmpR-binding sites in the upstream activation sequence of the ompC promoter in Escherichia coli: a single OmpR-binding site is capable of activating the promoter. J. Bacteriol. 172:501-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makino, K., H. Shinagawa, M. Amemura, S. Kimura, A. Nakata, and A. Ishihama. 1988. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli. Activation of pstS transcription by PhoB protein in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 203:85-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makino, K., H. Shinagawa, M. Amemura, T. Kawamoto, M. Yamada, and A. Nakata. 1989. Signal transduction in the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli involves phosphotransfer between PhoR and PhoB proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 210:551-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makino, K., M. Amemura, S. K. Kim, A. Nakata, and H. Shinagawa. 1993. Role of the σ70 subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation by activator protein PhoB in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 7:149-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makino, K., M. Amemura, T. Kawamoto, S. Kimura, H. Shinagawa, A. Nakata, and M. Suzuki. 1996. DNA binding of PhoB and its interaction with RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 259:15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makino, K., H. Shinagawa, and A. Nakata. 1985. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli K-12: regulation and role of the regulatory gene phoR. J. Mol. Biol. 184:231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 269:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Hackert, E., and A. M. Stock. 1997. The DNA-binding domain of OmpR: crystal structures of a winged helix transcription factor. Structure 5:109-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattison, K., R. Oropeza, N. Byers, and L. J. Kenney. 2002. A phosphorylation site mutant of OmpR reveals different binding conformations at ompF and ompC. J. Mol. Biol. 315:497-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattison, K., R. Oropeza, and L. J. Kenney. 2002. The linker region plays an important role in the inter-domain communication of the response regulator OmpR. J. Biol. Chem. 277:32714-32721. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mayer, M. P. 1995. A new set of useful cloning and expression vectors derived from pBlueScript. Gene 163:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizuno, T. 1997. Compilation of all genes encoding two-component phosphotransfer signal transducers in the genome of Escherichia coli. DNA Res. 4:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakashima, K., K. Kanamaru, H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 1991. Signal transduction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. A novel type of mutation in the phosphorylation domain of the activator protein, OmpR, results in a defect in its phosphorylation-dependent DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 266:10775-10780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamura, H., S. Hanaoka, A. Nagadoi, K. Makino, and Y. Nishimura. 2000. Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J. Mol. Biol. 295:1225-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pratt, L. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1994. OmpR mutants specifically defective for transcriptional activation. J. Mol. Biol. 243:579-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rampersaud, A., S. L. Harlocker, and M. Inouye. 1994. The OmpR protein of Escherichia coli binds to sites in the ompF promoter region in a hierarchical manner determined by its degree of phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12559-12566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russo, F. D., and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. EnvZ controls the concentration of phosphorylated OmpR to mediate osmoregulation of the porin genes. J. Mol. Biol. 222:567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo, F. D., J. M. Slauch, and T. J. Silhavy. 1993. Mutations that affect separate functions of OmpR the phosphorylated regulator of porin transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 231:261-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 51.Shinagawa, H., K. Makino, and A. Nakata. 1983. Regulation of the pho regulon in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetic and physiological regulation of the positive regulatory gene phoB. J. Mol. Biol. 168:477-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slauch, J. M., F. D. Russo, and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. Suppressor mutations in rpoA suggest that OmpR controls transcription by direct interaction with the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 173:7501-7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slauch, J. M., and T. J. Silhavy. 1989. Genetic analysis of the switch that controls porin gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Mol. Biol. 210:281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slauch, J. M., and T. J. Silhavy. 1991. cis-acting ompF mutations that result in OmpR-dependent constitutive expression. J. Bacteriol. 173:4039-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sola, M., F. X. Gomis-Ruth, L. Serrano, A. Gonzalez, and M. Coll. 1999. Three-dimensional crystal structure of the transcription factor PhoB receiver domain. J. Mol. Biol. 285:675-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tate, S., M. Kato, Y. Nishimura, Y. Arata, and T. Mizuno. 1988. Location of DNA-binding segment of a positive regulator, OmpR, involved in activation of the ompF and ompC genes of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 242:27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tran, V. K., R. Oropeza, and L. J. Kenney. 2000. A single amino acid substitution in the C terminus of OmpR alters DNA recognition and phosphorylation. J. Mol. Biol. 299:1257-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuzuki, M., K. Ishige, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Phosphotransfer circuitry of the putative multi-signal transducer, ArcB, of Escherichia coli: in vitro studies with mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 18:953-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuzuki, M., H. Aiba, and T. Mizuno. 1994. Gene activation by the Escherichia coli positive regulator, OmpR. Phosphorylation-independent mechanism of activation by an OmpR mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 242:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Utsumi, R., S. Katayama, M. Taniguchi, T. Horie, M. Ikeda, S. Igaki, H. Nakagawa, A. Miwa, H. Tanabe, and M. Noda. 1994. Newly identified genes involved in the signal transduction of Escherichia coli K-12. Gene 140:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volz, K. 1993. Structural conservation in the CheY superfamily. Biochemistry 32:11741-11753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wanner, B. L., and P. Latterell. 1980. Mutants affected in alkaline phosphatase, expression: evidence for multiple positive regulators of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. Genetics 96:353-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wanner, B. L. 1983. Overlapping and separate controls on the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol. 166:283-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wanner, B. L. 1993. Gene regulation by phosphate in enteric bacteria. J. Cell. Biochem. 51:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamada, M., K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and A. Nakata. 1990. Regulation of the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli: properties of phoR deletion mutants and subcellular localization of PhoR protein. Mol. Gen. Genet. 220:366-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]