Abstract

Haloferax volcanii, a halophilic archaeon, synthesizes three different proteins (α1, α2, and β) which are classified in the 20S proteasome superfamily. The α1 and β proteins alone form active 20S proteasomes; the role of α2, however, is not clear. To address this, α2 was synthesized with an epitope tag and purified by affinity chromatography from recombinant H. volcanii. The α2 protein copurified with α1 and β in a complex with an overall structure and peptide-hydrolyzing activity comparable to those of the previously described α1-β proteasome. Supplementing buffers with 10 mM CaCl2 stabilized the halophilic proteasomes in the absence of salt and enabled them to be separated by native gel electrophoresis. This facilitated the discovery that wild-type H. volcanii synthesizes more than one type of 20S proteasome. Two 20S proteasomes, the α1-β and α1-α2-β proteasomes, were identified during stationary phase. Cross-linking of these enzymes, coupled with available structural information, suggested that the α1-β proteasome was a symmetrical cylinder with α1 rings on each end. In contrast, the α1-α2-β proteasome appeared to be asymmetrical with homo-oligomeric α1 and α2 rings positioned on separate ends. Inter-α-subunit contacts were only detected when the ratio of α1 to α2 was perturbed in the cell using recombinant technology. These results support a model that the ratio of α proteins may modulate the composition and subunit topology of 20S proteasomes in the cell.

Proteasomes are large, energy-dependent proteases. These enzyme structures form nanocompartments within the cell (2, 27) that degrade proteins into oligopeptides of 3 to 30 amino acids in length by processive hydrolysis (1, 24). The catalytic core responsible for this proteolytic activity is a 20S particle, universally distributed among the Archaea, Eucarya, and gram-positive actinomycetes (10, 12). The 20S proteasome particle (11 to 12 nm in diameter and 15 nm in length) is a cylindrical bundle of four-stacked, heptameric rings. This barrel-shaped structure includes a central channel with narrow (1.3 nm) openings on each end which limits substrate access (32). Each opening is connected to a central chamber responsible for the hydrolysis of peptide bonds (20, 21, 25). “Unfoldases” such as the eucaryal 19S cap and archaeal PAN protein associate with 20S proteasomes and stimulate the energy-dependent degradation of proteins (17, 34, 37, 39).

The subunits that form 20S proteasomes have been classified into two related superfamilies (α and β) (9). The α proteins form the outer rings (18) and are required for the β proteins to be processed during formation of inner rings which harbor the active-site N-terminal threonine (13, 25, 26, 31, 38). The number of subunits forming 20S proteasomes varies. Many lower eucaryotes such as yeast produce a single symmetrical 20S proteasome of 14 different subunits (i.e., two copies each of α1 to α7 and β1 to β7) (20). Higher eucaryotes express additional subunits (e.g., β1i, β2i, β5i) that form auxiliary 20S proteasomes (e.g., the immunoproteasome) (19). Bacterial 20S proteasomes are typically much simpler, being composed of a single α-type and a single β-type subunit (12). The bacterium Rhodococcus erythropolis, however, is an exception and synthesizes a 20S proteasome composed of two α and two β subunits (36). Interestingly, genome analysis suggests that increased 20S proteasome complexity may actually be widespread among the Archaea, with several Creanarchaeotes and Euryarchaeotes encoding three proteasomal proteins (typically a single α-type and two β-type open reading frames [ORFs]) (27).

To date, Haloferax volcanii is the only archaeon that has been shown to synthesize three different proteins (α1, α2, and β) that are classified in the 20S proteasome superfamily (33). The α1 and β proteins form active 20S proteasomes; however, prior to this study, it was not clear whether α2 formed 20S proteasomes, and if so, with which proteins it associated. To further examine the unusual nature and topology of H. volcanii 20S proteasomes, α1, α2, and β were separately expressed with an epitope tag and purified from H. volcanii. Recombinant Escherichia coli was used to analyze the apparent flexibility of α subunit associations. In addition, 20S proteasomes purified from wild-type and mutant cells were analyzed by native gel electrophoresis and cross-linking. This series of approaches provided a model for how the composition and topology of 20S proteasomes may be modulated by the ratio of α subunits in the cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Biochemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.). Other organic and inorganic analytical grade chemicals were from Fisher Scientific (Atlanta, Ga.). Restriction endonucleases and DNA-modifying enzymes were from New England BioLabs (Beverly, Mass.). SnakeSkin dialysis tubing was from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). Desalted oligonucleotides were from Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, Tex.). Hybond-P membranes used for immunoblot were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.).

Strains, media and plasmids.

Bacterial strains, oligonucleotide primers, template DNA, and plasmids are summarized in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (37°C, 200 rpm). H. volcanii strains were grown in complex medium (ATCC 974) (42°C, 200 rpm). Media were supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin, 50 mg of kanamycin, or 0.1 mg of novobiocin per liter as needed.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used for this study

| Strain or plasmid (protein) | Phenotype or genotype (oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Life Technologies |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F−ompT [lon]hsdSB(rB−mB−) (an E. coli B strain) with DE3, a λ prophage carrying the T7 RNA polymerase gene | Novagen |

| E. coli GM2163 | F−ara-14 leuB6 fhuA31 lacY1 tsx78 glnV44 galK2 galT22 mcrA dcm-6 hisG4 rfbD1 rpsL 136 dam13::Tn9 xylA5 mtl-1 thi-1 mcrB1 hsdR2 | New England Biolabs |

| H. volcanii WFD11 | Cured of plasmid pHV2 | 6 |

| H. volcanii psmC-1 | WFD11 psmC disrupted using gyrB-gyrA′ (Nvr) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Apr; cloning vector | |

| pET24b | Kmr; expression vector | Novagen |

| pBAP5010 | Apr Nvr; 11-kb shuttle expression vector derived from pBAP5009 by insertion of citrate synthase gene; includes P2 promoter of the rRNA operon of H. cutirubrum | M. J. Danson (23) |

| pMLH3 | Nvr; includes gyrB-gyrA′ operon | 22 |

| pJAM202 (β-His) | Apr Nvr; 1,152-bp XbaI-to-DraIII fragment of pJAM621 blunt end ligated with a 9.9-kb BamHI-to-KpnI fragment of pBAP5010;psmB-H6 oriented with rRNA P2; β-His expressed in H. volcanii | This study |

| pJAM204 (α1-His) | Apr Nvr; 1,179-bp XbaI-to-DraIII fragment of pJAM622 blunt end ligated with a 9.9-kb BamHI-to-KpnI fragment of pBAP5010; psmA-H6 oriented with rRNA P2; α1-His expressed in H. volcanii | This study |

| pJAM205 (α2-His) | Apr Nvr; 1,170-bp XbaI-to-DraIII fragment of pJAM623 blunt end ligated with a 9.9-kb BamHI-to-KpnI fragment of pBAP5010; psmC-H6 oriented with rRNA P2; α2-His expressed in H. volcanii | This study |

| pJAM600 (α2, α1-His) | Kmr; 0.89-kb XbaI (blunt)-to-BlpI fragment of pJAM622 ligated into the HindIII (blunt) and BlpI sites of pJAM619; α2 and α1-His expressed in E. coli | This study |

| pJAM601 (α1, α2-His) | Kmr; 0.88-kb XbaI (blunt)-to-BlpI fragment of pJAM623 ligated into the HindIII (blunt) and BlpI sites of pJAM618; α1 and α2-His expressed in E. coli | This study |

| pJAM618 (α1) | Kmr; 795-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from the H. volcanii genome ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmA and 27 bp of genomic DNA downstream; α1 expressed in E. coli 5′-CTGCCCTCATATGCAGGGACAAGCG-3′ and 5′-CTGCCAAGCTTGCGAGAACGGGAAC-3′ (NdeI and HindIII sites in bold) | This study |

| pJAM619 (α2) | Kmr; 806-bp fragment from pJAM653 ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmC and 31 bp of genomic DNA downstream; α2 expressed in E. coli | This study |

| pJAM620 (βΔ-His) | Kmr; 594-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from the H. volcanii genome ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmBΔH6 which has a deletion of the codons encoding amino acids 2 through 49; βΔ-His expressed in E. coli (5′-CTGCCCTCATATGACGACCACCGTC-3′ and 5′-TTTGAAGCTTTTCGAGGCCTTCGAAG-3′ (NdeI and HindIII sites in bold) | This study |

| pJAM621 (β-His) | Kmr; 738-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from the H. volcanii genome ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmB-H6;β-His expressed in E. coli (5′-CTTACCTCATATGCGTACCCCGACTC-3′ and 5′-TTTGAAGCTTTTCGAGGCCTTCGAAG-3′)(NdeI and HindIII sites in bold) | This study |

| pJAM622 (α1-His) | Kmr; 765-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from the H. volcanii genome ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmA-H6; α1-His expressed in E. coli (5′-CTGCCCTCATATGCAGGGACAAGCG-3′ and 5′-TTTGAAGCTTCTCTTCGGTCTGTTC-3′)(NdeI and HindIII sites in bold) | This study |

| pJAM623 (α2-His) | Kmr; 756-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from pJAM653 ligated into pET24b using NdeI and HindIII; carries psmC-H6; α2-His expressed in E. coli (5′-TT CATATGAACCGAAACGACAAGCAGG-3′ and 5′-AATTAAGCTTCTCCTCGCGTTCGTC-3′)(NdeI and HindIII sites in bold) | This study |

| pJAM653 | Apr; 784-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification from the H. volcanii genome ligated into pUC19 using HincII; carries psmC and 31 bp of DNA downstream; intermediate cloning step for generation of pJAM619 and pJAM623) (5′-TTCATATGAACCGAAACGACAAGCAGG-3′ and 5′-TGTTACCGTCGGTCGGGCTCCCGTCTG-3′)(NdeI site in bold) | This study |

| pJAM201 | Apr Nvr; 2.8-kb BstBI fragment of H. volcanii DNA carrying psmC flanked by 1 kb of genomic DNA blunt end ligated into AatII site of pUC19; psmC disrupted at AatII by gyrB-gyrA′ operon | This study |

PCR was used to introduce restriction enzyme sites for directional cloning of psmA, psmB, and psmC into plasmid pET24b for expression in E. coli. The fidelity of all PCR-amplified products was confirmed by DNA sequencing using the dideoxy termination method (30) and a LICOR automated DNA sequencer (DNA Sequencing Facility, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida). The start codons of psmA, psmB, and psmC were positioned 8 bp downstream of the ribosome binding sequence of pET24b using NdeI. For epitope tagging, the 3′ end of the gene was modified by PCR to remove the stop codon and provide an in-frame C-terminal addition of residues (KLAAALEHHHHHH) to the protein. For coexpression of α1 and α2 in E. coli, the psmA-H6 and psmC-H6 genes were positioned downstream of psmC and psmA, respectively, using DNA fragments isolated from the pET24b-based plasmids.

For expression of epitope-tagged proteins in H. volcanii, the modified proteasomal genes (psmA-H6, psmB-H6, and psmC-H6) were isolated from the pET24b-based plasmids by restriction enzyme digestion (Table 1) and were blunt end ligated into the BamHI and KpnI sites of plasmid pBAP5010. The DNA fragments used for ligation included not only the modified gene but also the ribosome binding sequence and T7 terminator of the original pET24b. The start codon of each modified gene was positioned 75 bp downstream of the Halobacterium cutirubrum rRNA P2 promoter. This resulted in the generation of shuttle expression plasmids pJAM202, pJAM204, and pJAM205 for the synthesis of β-, α1-, and α2-His proteins, respectively. For the generation of H. volcanii psmC-1, strain WFD11 was transformed with a suicide plasmid (pJAM201) and selected for growth in the presence of novobiocin. Colonies were screened for the absence of α2 by immunoblotting using anti-α2 antibodies (described below). Strains which did not produce detectable levels of α2 were further screened for double recombination by PCR using the oligonucleotides 5′-TTCATATGAACCGAAACGACAAGCAGG-3′ and 5′-TGTTACCGTCGGTCGGGCTCCCGTCTG-3′, with genomic DNA as a template.

DNA purification and transformation.

Genomic DNA was isolated from H. volcanii strains as previously described (33). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a Quantum Prep plasmid miniprep kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). DNA fragments were eluted from 0.8% SeaKem GTG agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) gels with 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.5) using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). H. volcanii WFD11 cells were transformed according to the method of Cline et al. (8) using plasmid DNA isolated from E. coli GM2163 strains.

Protein synthesis and purification.

Expression of heterologous genes was induced from plasmids in E. coli BL21(DE3) as previously described (26). Epitope-tagged proteasome proteins were synthesized from plasmids in recombinant H. volcanii strains grown to late stationary phase. Protein purification steps were done at room temperature unless otherwise indicated. Buffers typically included high salt (2 M) to mimic the ionic strength of the cytosol of this halophilic archaeon. For non-histidine-tagged proteins, buffers were supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol. For all purifications, centrifugations were done at 16,000 × g (20 to 30 min, 4°C). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −70°C. Cells were resuspended in 2.5 to 6 volumes (wt/vol) of lysis buffer and lysed by passage through a French pressure cell at 20,000 lb/in2 followed by centrifugation. Dialysis was at 4°C for 16 h followed by centrifugation. Samples were filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size filter) prior to column application. Fractions were monitored for peptidase activity using N-Suc-LLVY-Amc (N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) or by staining with Coomassie blue R-250 after separation by reducing 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (33). Molecular mass standards for SDS-PAGE included phosphorylase b (97.4 kDa), serum albumin (66.2 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (31 kDa), trypsin inhibitor (21.5 kDa), and lysozyme (14.4 kDa) (Bio-Rad). Samples were stored at 4°C. Native molecular masses were determined by applying samples to a calibrated Superose 6 HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia) as previously described (33). Molecular mass standards included serum albumin (66 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), β-amylase (200 kDa), apoferritin (443 kDa), and thyroglobulin (669 kDa) (Sigma).

(i) Purification of α1 and α2 from recombinant E. coli.

The α1 and α2 proteins were purified from E. coli strains carrying plasmids pJAM618 and pJAM619, respectively. Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.2 containing 150 mM NaCl (buffer A). Lysate was dialyzed into 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.2 containing 2 M NaCl (buffer B). The supernatant was dialyzed into 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer at pH 7.2 containing 1.5 M NaCl-2.2 M (NH4)2SO4 (buffer C). The supernatant (6 mg of protein per ml) was applied to a DEAE-cellulose (Sigma) column (2.6 cm by 10 cm) equilibrated with buffer C. The column was washed with buffer C, and protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris-Cl buffer, pH 7.2, containing 2.1 M NaCl-1.6 M (NH4)2SO4 (buffer D). Sample was dialyzed into buffer B, concentrated (5 to 10 mg ml−1) by dialysis against PEG 8000, and applied to the Superose 6 column equilibrated in buffer B.

(ii) Purification of histidine-tagged proteasomal proteins.

The histidine-tagged α1, α2, β, and βΔ proteins were purified from E. coli strains carrying plasmids pJAM622, pJAM623, pJAM621, and pJAM620, respectively. Cells were lysed in buffer B containing 10 mM imidazole. Sample was applied to a Ni2+-Sepharose column (4.8 by 0.8 cm) (Pharmacia) equilibrated in lysis buffer and washed with buffer B (10 ml) containing 60 mM imidazole. Protein was eluted in buffer B containing 500 mM imidazole. Sample was applied to a Superose 6 HR 10/30 column equilibrated in buffer B containing 10% glycerol. Similar procedures were used for coexpression of the α proteins in E. coli, with the following modifications. E. coli strains carrying plasmids pJAM600 and pJAM601 were lysed in buffer A. Supernatant was dialyzed into buffer B with 5 mM imidazole. Aliquots were heated (15 min, 37°C), chilled (15 min, 0°C), and centrifuged. Heat-treated and unheated samples were applied to the Ni2+-Sepharose column. Similar procedures were used for purification of the His-tagged α1, α2, and β proteins from H. volcanii carrying plasmids pJAM204, pJAM205, and pJAM202, with the following modifications. Buffers were supplemented with 10% glycerol. Cell lysate was directly subjected to Ni2+-Sepharose chromatography for analysis of proteasomal subunit associations and ratios. For specific activity measurements (Table 2), 20S proteasomes were purified to homogeneity by treating cell lysate with PEG8000 and heat, as previously described (33), prior to affinity and gel filtration chromatography.

TABLE 2.

Subunit ratios of 20S proteasomes purified from H. volcanii strains

| Strain | Subunit | Molar ratioa | Sp actb |

|---|---|---|---|

| WFD11c | α1 | 0.304 | 238 ± 8 |

| α2 | 0.190 | ||

| β | 0.505 | ||

| psmC-1 | α1 | 0.538 | 280 ± 2 |

| β | 0.462 | ||

| WFD11(pJAM204) | α1 ± His | 0.416 | 208 ± 10 |

| α2 | 0.124 | ||

| β | 0.460 | ||

| WFD11(pJAM205) | α1 | 0.201 | 236 ± 10 |

| α2 ± His | 0.184 | ||

| β | 0.615 | ||

| WFD11(pJAM202) | α1 | 0.313 | 231 ± 21 |

| α2 | 0.158 | ||

| β ± His | 0.530 |

20S proteasomes were purified from the strain indicated and separated by SDS-PAGE. H. volcanii WFD11 (pJAM205) purified proteins were detected by chemiluminescence after immunoblotting. All others were stained with Coomassie blue R-250 and analyzed by densitometry. Bovine serum albumin and α1-His, α2-His, and β-His from recombinant E. coli were used as standards. Molecular mass was calculated based on GenBank accession numbers AF126260, AF126261, and AF126262. The additional C-terminal residues of the modified proteins were included in the calculations as needed.

Specific activity of N-Suc-LLVY-Amc hydrolysis measured as nanomoles of 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin produced per minute per milligram of protein at 60°C. Results are means ± SEM.

Fraction A was used for analysis of strain WFD11. This fraction appears as 20S proteasomes when visualized by TEM, migrates as a single band on a native gel, and is composed of α1, α2, and β subunits.

(iii) Purification of 20S proteasomes from H. volcanii.

20S proteasomes were purified from H. volcanii strains WFD11 and psmC-1 as previously described (33), with the following modifications. Protein was eluted from the DEAE-cellulose column using a linear gradient of 1.5 to 2.1 M NaCl and 2.2 to 1.6 M (NH4)2SO4 in 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.2. Sample was dialyzed against 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 with 2 M NaCl and applied to a Bio-scale hydroxyapatite type I column (Bio-Rad) equilibrated in the same buffer. 20S proteasomes were eluted with a linear sodium phosphate gradient (10 to 500 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.2) supplemented with 2 M NaCl.

Antibody preparation and immunoanalysis.

Proteins (βΔ-His, α1, and α2) purified from recombinant E. coli were separated by SDS-PAGE, excised from the gel, and used as antigens to raise polyclonal antibodies in rabbits (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, Pa.). For chromogenic Western blots, antigens were detected using primary antibodies (1:10,000) and alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody raised in goat (1:20,000) (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.). For quantitative Western blots, antigens were detected using primary antibodies (α1, 1:10,000; α2, 1:1,000; β, 1:4,000) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody raised in goat (α1, 1:10,000; α2, 1:2,000; β, 1:4,000) by chemiluminescence with ECL Plus according to the supplier's recommendations (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The β-His, α1-His, and α2-His proteins purified from recombinant E. coli were included on these blots as quantitative standards (2 to 80 ng per lane).

RESULTS

Synthesis of epitope-tagged α1, α2, and β in H. volcanii.

To determine whether α2 is involved in the formation of active 20S proteasomes, the α2 protein was expressed with an epitope tag (α2-His) from plasmid pJAM205 in H. volcanii. This plasmid was designed for constitutive transcription of the modified proteasome gene (psmC-H6) from the H. cutirubrum rRNA P2 promoter. The T7 terminator and ribosome binding sequence from pET24b were included to facilitate protein synthesis. Although leaderless transcripts have been described for the haloarchaea (3, 4, 7, 11, 28, 29), the 3′-end 16S rRNA sequences of E. coli and H. volcanii are highly related (HO-AUUCCUCCACUAGGUUGG for E. coli [5] and HO-UCCUCCACUAGGUCGG for H. volcanii [accession no. AB074566]). Thus, it was predicted that the pET24b-based ribosome binding site used for protein synthesis in E. coli would function in H. volcanii.

For comparison to α2-His, the genes encoding α1 and β proteins were similarly modified (psmA-H6 and psmB-H6 encoding α1-His and β-His) and separately synthesized in vivo using plasmids pJAM204 and pJAM202. The epitope tag (His) consisted of a seven-amino-acid linker followed by six histidine residues at the C terminus of the protein to enable Ni2+-affinity purification. Based on three-dimensional modeling (33), this type of modification was expected to result in minimal, if any, perturbation to 20S proteasome structure. This modeling approach also suggested that the C termini of all three subunits would be located on the surface of the 20S proteasome cylinder and, thus, would be accessible for binding during affinity chromatography. In contrast, the N termini of α-type proteasomal subunits are essential for auto-assembly into the heptameric rings of 20S proteasomes (38). Furthermore, the β subunit of 20S proteasomes purified from H. volcanii is processed at its N terminus to expose the presumed active-site threonine (33).

Quantitative immunoblotting was used to analyze the levels of 20S proteasome proteins produced in the recombinant and parent strains of H. volcanii. Cell lysate was prepared from stationary-phase cultures and probed with polyclonal antibodies specific for each of the proteasomal proteins (see Materials and Methods). This approach revealed that cells transformed with the expression plasmid pJAM204 synthesized α2 (with or without His) at four times the level of the parent strain. Similarly, α1 (with or without His) was elevated five- to sevenfold when homologously expressed with an epitope tag. When β-His was synthesized with the 49-residue propeptide, the overall levels of β were enhanced only twofold. Accumulation of unprocessed forms of β-His was not observed (detection limit of 1.2 × 10−13 mol per cell). Modification of operon structure and/or amplified copy number of the proteasomal genes is the likely reason for the observed increases in the levels of the proteasomal proteins in the recombinant strains. The basis for the differences in the overexpression levels of β compared to α1 or α2 remains to be determined. It is possible that posttranscriptional differences influenced synthesis, since similar genetic elements were used during plasmid construction (i.e., P2 promoter, T7 terminator, and ribosome binding sequence) and the positioning of the ORFs with respect to these elements was identical. However, differences in native genetic elements located within the ORFs that may drive transcription or translation cannot be ruled out. Interestingly, the observed perturbations in the levels of the individual proteasomal proteins had no apparent influence on the growth rate or cell yield based on comparison of recombinant and parent strains grown on rich medium under microaerobic conditions (200 rpm, 42°C) (data not shown).

α2 protein is a 20S proteasome subunit.

Ni2+-affinity and gel filtration chromatography were used to purify and analyze the epitope-tagged protein complexes from the recombinant H. volcanii strains. Initial analysis of α2-His by Coomassie blue staining revealed that the 1,519-Da epitope tag resulted in its comigration with α1 on SDS-PAGE gels. Therefore, Western blots using antibodies specific for each proteasomal protein were included for comparison.

An analysis of proteins purified from H. volcanii(pJAM205) expressing the α2-His protein (Fig. 1) revealed two α2-specific polypeptides with molecular masses consistent with α2 and α2-His. An additional, unexpected α2-specific polypeptide was observed (fractions 35 and 44) which had a molecular mass of 800 Da less than that of α2-His but greater than that of the wild-type α2 protein. The reason for this third α2-specific antigen has not been determined. It is possible that α2-His is susceptible to cleavage, either in the cell or during purification. It is also possible that an internal start codon is recognized which results in the synthesis of an α2-His polypeptide with a shortened N terminus. This second explanation, however, is less likely based on the sequence of psmC (33).

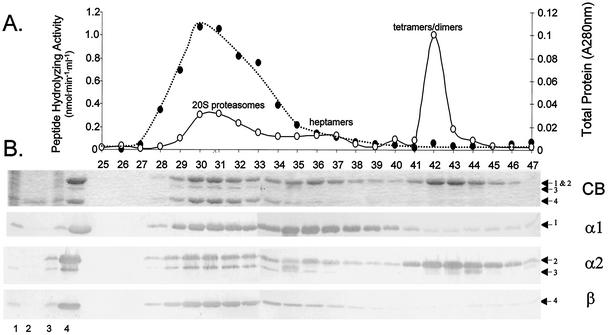

FIG. 1.

Association of the α1, α2, and β proteasomal proteins as demonstrated by purification of α2-His-containing complexes. (A) Proteins were purified from recombinant H. volcanii(pJAM205) using Ni2+-Sepharose and Superose 6 gel filtration. Gel filtration fraction numbers are indicated on the x axis. Total protein measured by A280 (○) and N-Suc-LLVY-Amc-hydrolyzing activity (•) are indicated. (B) Proteins were separated by reducing 12% PAGE with SDS and analyzed by Coomassie blue (CB) staining or Western blotting using antibodies raised against α1, α2, and β as indicated on the right. H. volcanii(pBAP5010) cell lysate (lane 1) and Ni2+-purified fractions (lane 2) were included as controls. H. volcanii(pJAM205) cell lysate (lane 3), Ni2+-purified fractions (lane 4), and Superose 6 gel filtration fractions 25 to 47 are shown. Arrows to the right indicate α1 (band 1)-, α2 (bands 2 and 3)-, and β (band 4)-specific proteins.

Further analysis by gel filtration revealed that α2-His was associated with high-molecular-mass complexes of 600 kDa (fractions 29 to 33) (Fig. 1). The complexes were comparable in structure to 20S proteasome particles when analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (data not shown). Likewise, their chymotrypsin-like activity was similar to that of 20S proteasomes purified from wild-type H. volcanii (Table 2) (33). The recombinant 20S proteasomes were composed of α1, α2 (with or without His), and β in a molar ratio of approximately 1:1:3 (Table 2). The reason for the less-than-1:1 ratio of α to β subunits is unclear and contrasts with the 1:1 ratio observed for the other H. volcanii 20S proteasomes described in this study (Table 2). It may be a reflection of the methods employed for analysis, since the α2-His-containing 20S proteasomes were the only complexes requiring quantitative immunoblotting for estimating the molar ratio of subunits (due to the comigration of α2-His and α1 on SDS-PAGE gels).

Complexes containing α2-His with molecular masses of less than 600 kDa were also purified; however, these had no apparent peptidase activity (Fig. 1). These inactive fractions were composed of α1 and α2-His in varying ratios, with the predominant protein peak estimated to be dimers to tetramers of the α proteins. Unmodified α2 was not detected in these low-molecular-mass fractions.

Together, these results reveal that α2 can associate with α1 and β to form active 20S proteasomes in H. volcanii. The presence of a second β subunit (i.e., β2) which comigrates with the β subunit on SDS-PAGE cannot be ruled out at this time. However, this speculative β2 protein is not detected when sequencing the N terminus of the β subunit. Furthermore, Southern blotting using a degenerate probe based on the N-terminal sequence of β (33) and the partial genome sequence of H. volcanii (V. G. DelVecchio, personal communication) do not predict a second β protein. Based on the results presented above, altering the C terminus of α2 by the addition of a poly-His tag did not inhibit 20S proteasome formation or peptidase activity. However, the preferential accumulation of unmodified α2 in the 20S proteasome fractions suggests that this modification influenced the affinity of α2 for 20S proteasome complex formation.

For comparison, α1-His-containing proteins were purified from H. volcanii(pJAM204) and analyzed using similar methods (Fig. 2). Western blotting with α1-specific antibody revealed that a significant portion (10 to 25%) of the α1-His polypeptide was cleaved to generate a protein slightly (500 Da) smaller than α1-His but larger than the wild-type α1 protein. This α1-specific antigen was present in the majority of α1-His complexes (fractions 31 to 41). Internal start codons are not predicted to generate this shortened form of the α1-His protein. Whether a related protease is involved in cleavage of both α1- and α2-His remains to be determined.

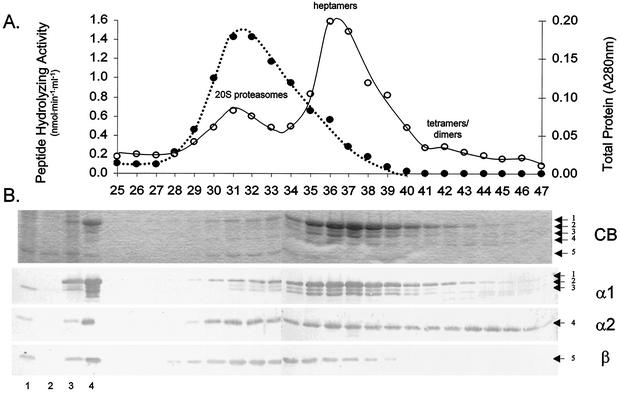

FIG. 2.

Association of the α1, α2, and β proteasomal proteins as demonstrated by purification of α1-His-containing complexes. The figure is similar to Fig. 1, except plasmid pJAM204 was substituted for pJAM205. (A) Proteins purified by gel filtration. (B) Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. Arrows to the right indicate α1 (bands 1 to 3)-, α2 (band 4)-, and β (band 5)-specific proteins.

Similar to α2-His, the α1-His protein was purified in high-molecular-mass (600 kDa) complexes. These complexes contained all three proteasomal proteins (α1, α2, and β) in a molar ratio of approximately 4:1:5 (Table 2). This high-molecular-mass fraction had biochemical properties similar to the H. volcanii wild-type 20S proteasomes (33), including chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (Table 2) and architecture (as visualized by TEM). Interestingly, a large portion of α1-specific antigen purified as heptamers in association with α2 (fractions 36 to 41). In fact, the ratio of heptamers to 20S proteasomes was almost 4:1 as estimated by A280. Low levels of α1-His and α2 were also detected in complexes smaller than heptamers. Both heptamers and fractions of lower molecular mass had no measurable N-Suc-LLVY-Amc hydrolyzing activity. Thus, when the ratio of α1 to α2 was modified by overproduction of α1-His, the rate-limiting step in assembly of α1 into proteasomes appeared to be after the formation of heptamers. In contrast, high-level production of α2-His resulted in the accumulation of low-molecular-mass dimers to tetramers, suggesting that heptamerization limits incorporation of α2 into proteasomes. These results reveal that α1 and α2 are capable of interacting, since these two proteins were found as dimeric to heptameric complexes that did not contain β-specific proteins.

Overproduction of unprocessed β-His in H. volcanii(pJAM202) facilitated purification of 20S proteasomes that were composed of α1-, α2-, and β-specific proteins in a molar ratio of approximately 3:1.5:5 (Table 2). The complexes had typical 20S proteasome structures and were fully active in hydrolyzing N-Suc-LLVY-Amc (Table 2). In contrast to the α proteins, when unprocessed β protein was overproduced in the cell the majority of β protein was processed and purified as 20S proteasomes (data not shown). However, about a third of the β protein purified as dimers to monomers. Based on N-terminal sequence analysis of these low-molecular-mass fractions, the β protein was processed to expose the same N-terminal threonine described previously for H. volcanii 20S proteasomes (33). These low-molecular-mass fractions were β specific, with no other proteins detected by Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE gels. Although further investigation is needed, these results reveal that not all processed β protein is associated with 20S proteasomes in these recombinant cells.

Overall, these findings are consistent with the current model for archaeal 20S proteasome assembly (2, 38) and provide evidence that α2 associates in 20S proteasomes with active β subunits. The results also substantiate the finding that α1 is the predominant α-type subunit incorporated into 20S proteasomes. The α2 protein was only about one-third of the total α protein incorporated into the β-His-containing 20S proteasomes (Table 2). Together, these results demonstrate that 20S proteasomes composed of all three subunits (α1, α2, and β) can assemble in H. volcanii.

Association of α1 and α2.

To further address the interactions of the α-type subunits, E. coli strains were modified to independently synthesize α1 and α2 with and without C-terminal histidine tags. Salt was included in the purification buffers at high concentrations to mimic the unusually high ionic strength of the H. volcanii cytosol. Based on TEM, the α1 and α2 proteins produced separately in recombinant E. coli formed rings after dialysis into buffer supplemented with 2 M salt (Fig. 3). E. coli strains were also constructed that (i) coexpressed α1-His and α2 and (ii) coexpressed α1 and α2-His. Affinity and gel filtration chromatography of these proteins after dialysis into high salt (2 M) revealed that α1 and α2 were able to associate as heterogeneous dimers to heptamers in recombinant E. coli (data not shown). These results suggested that there was flexibility in the types of α1 and α2 interactions that were possible. Modifying the ratios of α1 to α2 during expression in E. coli directly influenced the composition of the α-type heptamers that were formed (i.e., homo- to hetero-oligomers).

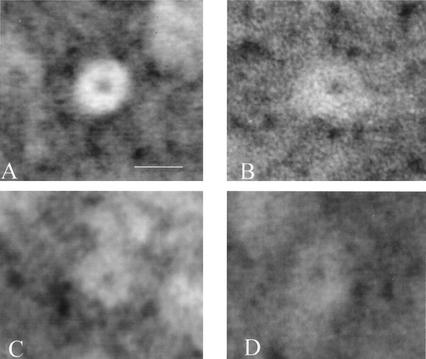

FIG. 3.

Recombinant α1 and α2 proteins form ring structures. Transmission electron micrographs of negatively stained proteins are shown. An end-on view of a 20S proteasome (A) purified from H. volcanii(pJAM204) is included for comparison. (B and C) Typical end-on view of α1 (B) and α2 (C) purified from recombinant E. coli. (D) Typical end-on view of ring observed for the 200-kDa fraction purified from H. volcanii(pJAM204) which contains α1-His, α1, and α2 proteins. Bar, 12 nm. Samples were prepared and viewed on a Zeiss EM-10CA transmission electron microscope as previously described (33).

Flexibility in complex formation has been observed for other α-type proteasomal subunits. Often when eucaryal α-type proteins are independently expressed in recombinant E. coli, the proteins self-associate, even though this type of interaction is not evident in purified 20S proteasomes. For example, the human α7 (HsC8) and Trypanosoma brucei α5 self-assemble into single, double, and even four-stacked protein rings when synthesized in recombinant E. coli (16, 35). In addition, the human α7 protein forms hetero-oligomeric rings when coexpressed with α1 (PROS27) and α6 (PROS30), both of which are adjacent to α7 in the outer rings of wild-type 20S proteasomes (15). Likewise, four different 20S proteasomes can be synthesized by expressing different combinations of R. erythropolis α1, α2, β1, and β2 in recombinant E. coli (36). However, only a single 20S proteasome containing all four subunits has been purified from R. erythropolis.

Association of α1 and α2 in 20S proteasomes from H. volcanii.

Previous work revealed that the 20S proteasomes of H. volcanii dissociate into monomers when exposed to low-salt buffers (33). Similar results have recently been observed for the 20S proteasome purified from Haloarcula marismortui (14). During this study it was discovered that low levels of CaCl2 (10 mM) stabilized the H. volcanii 20S proteasomes in the absence of salt without influencing peptide (N-Suc-LLVY-Amc)-hydrolyzing activity. This enabled 20S proteasomes purified from H. volcanii to be separated by native gels pre-equilibrated in the presence of CaCl2.

To directly address the type of α1-α2 subunit interactions present in H. volcanii, a protein fraction (A) was purified from stationary-phase wild-type cells that contained all three subunits in an α1-α2-β molar ratio of 1:1:2 (Table 2). For comparison, 20S proteasomes composed of α1 and β in an equimolar ratio were purified from a mutant strain (psmC-1) that did not produce α2. Both the α1-α2-β proteasome (fraction A) and α1-β proteasome migrated as distinct bands on native gels, suggesting that each formed a separate complex (Fig. 4). These two complexes were responsible for the majority of chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (N-Suc-LLVY-Amc-hydrolyzing activity) detected in the cell lysate (data not shown), and both 20S proteasomes hydrolyzed N-Suc-LLVY-Amc at comparable rates (Table 2). This suggests that the α1-α2-β proteasome identified in this study is the prevalent ancillary 20S proteasome in stationary-phase H. volcanii.

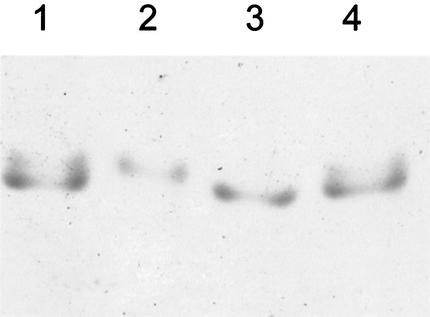

FIG. 4.

Native gel of H. volcanii 20S proteasomes reveals two distinct complexes. Lanes 2 and 3, α1-α2-β and α1-β proteasomes purified from H. volcanii WFD11 and psmC-1, respectively; lanes 1 and 4, equimolar mixture of the two proteasomes. Native gels containing 5% polyacrylamide were pre-equilibrated and run with 25 mM Tris-192 mM glycine buffer (pH 8.3) supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2. Proteins were stained with Coomassie blue R-250.

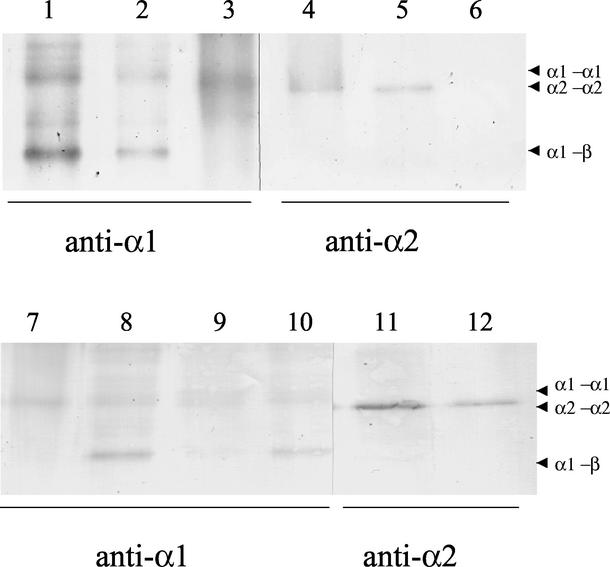

To further define the subunit topology of these wild-type 20S proteasomes, the enzymes were separately cross-linked with glutaraldehyde using conditions optimized for dimer formation. In addition, β-His-containing 20S proteasomes were included, since these are likely to be a mixture of 20S proteasomes with all possible α subunit interactions. The α1 and α2 proteins purified separately from recombinant E. coli were included as controls. The cross-linked products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for each proteasomal protein (Fig. 5). Probing with the anti-α2 antibody revealed a distinct band (63 kDa) which was present for the α1-α2-β and β-His proteasomes but was not detected for the α1-β proteasomes. This antigen appeared to be an α2-specific dimer, since it was readily separated from all α1- and β-specific products and migrated analogously to the α2 dimer from recombinant E. coli. A separate α1-specific band (65 kDa) was identified for all three of the 20S proteasomes examined. This common α1-specific band migrated similarly to the α1 dimer from recombinant E. coli. In addition, α1-β dimers were observed for all three proteasomes and α2-β dimers were detected for all but the α1-β proteasomes (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Cross-linking of H. volcanii 20S proteasomes reveals α1-α1 and α2-α2 contacts. The 20S proteasomes (300 nM) and α proteins (10 μM) were incubated (10 to 60 min, 37°C) in buffer B containing 10% glycerol and 0.22% glutaraldehyde. The cross-linking reaction was quenched with 1× 2 M Tris-Cl at pH 8.5 followed by precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Products and molecular mass standards (see Materials and Methods) were separated by reducing 7.5% PAGE with SDS. Specific antigens were detected by chromogenic Western blotting using antibodies raised against α1 (lanes 1 to 3 and 7 to 10), α2 (lanes 4 to 6 and 11 and 12), and βΔ-His (data not shown). Samples included the α1-β proteasome from H. volcanii psmC-1 (lanes 1, 6, and 8), the α1-α2-β proteasome from H. volcanii WFD11 (lanes 2, 5, 10, and 11), α1 (lanes 3 and 7) and α2 (lane 4) from recombinant E. coli(pJAM618) and E. coli(pJAM619), and β-His-containing proteasomes from H. volcanii(pJAM202) (lanes 9 and 12). Arrowheads indicate putative dimers.

Although α1-α2 interactions cannot be ruled out, these results strongly support the existence of an α1-α2-β proteasome in stationary-phase cells which is composed primarily of α1-α1, α2-α2, α1-β, and α2-β contacts. Thus, based on our current understanding of 20S proteasome structure, it is likely that this proteasome is formed from four homoheptameric rings with two inner β-rings and two outer α-rings of different subunit composition (α1 and α2). This would be the first example of a 20S proteasome with this type of asymmetry.

Although heterogeneous heptamers of α1 and α2 were observed in recombinant E. coli as well as recombinant H. volcanii, it is possible that these intermediate complexes were formed as a result of perturbations in the ratio of α1 to α2. Alternatively, it may be that α1-α2 associations do exist in 20S proteasomes but were not detected by our cross-linking methods. It is also possible that the 20S proteasome complexes purified from stationary-phase cells are a snapshot of those synthesized in the cell. The interactions between α1 and α2 may actually be dynamic; the cell may generate assembly intermediates composed of α1-α2 contacts that enable it to rapidly transition from α1-β to α1-α2-β proteasomes during growth.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that H. volcanii synthesizes at least two 20S proteasomes that differ in α subunit composition and topology. Why H. volcanii would synthesize more than one type of 20S proteasome remains to be determined. Since the α1 and α2 proteins share only 55.5% identity, there are significant structural differences in the homoheptameric rings formed by these two proteins. These differences are predicted to include residues preceding the N-terminal α-helix HO, located at the ends of the cylinder, as well as the loop restricting the 13-Å channel opening (based on comparison to the Thermoplasma acidophilum 20S proteasome crystal structure [25]). Thus, it is proposed that by modulating the levels of α1 and α2 proteins H. volcanii may control distinct structural domains at the ends of the 20S proteasome cylinder. This in turn may influence the gating and/or type of ATP-dependent unfoldases that interact with the 20S proteasome and, potentially, the type of substrate recognized for destruction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Francis Davis and Jack Shelton for DNA sequencing. We thank Henry Aldrich and Donna Williams for help with transmission electron micrographs. We also thank James Lee, Ainsley Davis, and Andy Calhoun for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the NIH (GM57498-03) and the Florida Agricultural Experiment Station (Journal Series R-09097).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopian, T. N., A. F. Kisselev, and A. L. Goldberg. 1997. Processive degradation of proteins and other catalytic properties of the proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1791-1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister, W., J. Walz, F. Zühl, and E. Seemüller. 1998. The proteasome: paradigm of a self-compartmentalizing protease. Cell 92:367-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betlach, M., J. Friedman, H. W. Boyer, and F. Pfeifer. 1984. Characterization of a halobacterial gene affecting bacterio-opsin gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:7949-7959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanck, A., and D. Oesterhelt. 1987. The halo-opsin gene. II. Sequence, primary structure of halorhodopsin and comparison with bacteriorhodopsin. EMBO J. 6:265-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius, J., M. L. Palmer, P. J. Kennedy, and H. F. Noller. 1978. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:4801-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlebois, R. L., W. L. Lam, S. W. Cline, and W. F. Doolittle. 1987. Characterization of pHV2 from Halobacterium volcanii and its use in demonstrating transformation of an archaebacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8530-8534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung, J., K. J. Danna, E. M. O'Connor, L. B. Price, and R. F. Shand. 1997. Isolation, sequence, and expression of the gene encoding halocin H4, a bacteriocin from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax mediterranei R4. J. Bacteriol. 179:548-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cline, S. W., W. L. Lam, R. L. Charlebois, L. C. Schalkwyk, and W. F. Doolittle. 1989. Transformation methods for halophilic archaebacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 35:148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coux, O., H. G. Nothwang, I. S. Pereira, F. R. Targa, F. Bey, and K. Scherrer. 1994. Phylogenic relationships of the amino acid sequences of prosome (proteasome, MCP) subunits. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245:769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlmann, B., F. Kopp, L. Kuehn, B. Niedel, G. Pfeifer, R. Hegerl, and W. Baumeister. 1989. The multicatalytic proteinase (prosome) is ubiquitous from eukaryotes to archaebacteria. FEBS Lett. 251:125-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DasSarma, S., U. L. RajBhandary, and H. G. Khorana. 1984. Bacterio-opsin mRNA in wild-type and bacterio-opsin deficient Halobacterium halobium strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:125-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Mot, R., I. Nagy, J. Walz, and W. Baumeister. 1999. Proteasomes and other self-compartmentalizing proteases in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol. 7:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenteany, G., R. F. Standaert, W. S. Lane, S. Choi, E. J. Corey, and S. L. Schreiber. 1995. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science 268:726-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzetti, B., G. Schoehn, D. Garcia, R. W. H. Ruigrok, and G. Zaccai. 2002. Characterization of the proteasome from the extremely halophilic archaeon Haloarcula marismortui. Archaea 1:53-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerards, W. L., W. W. de Jong, H. Bloemendal, and W. Boelens. 1998. The human proteasomal subunit HsC8 induces ring formation of other α-type subunits. J. Mol. Biol. 275:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerards, W. L., J. Enzlin, M. Haner, I. L. Hendriks, U. Aebi, H. Bloemendal, and W. Boelens. 1997. The human α-type proteasomal subunit HsC8 forms a double ring-like structure, but does not assemble into proteasome-like particles with the β-type subunits HsDelta or HsBPROS26. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10080-10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glickman, M. H., D. M. Rubin, O. Coux, I. Wefes, G. Pfeifer, Z. Cjeka, W. Baumeister, V. A. Fried, and D. Finley. 1998. A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell 94:615-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grizwa, A., W. Baumeister, B. Dahlmann, and F. Kopp. 1991. Localization of subunits in proteasomes from Thermoplasma acidophilum by immunoelectron microscopy. FEBS Lett. 290:186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groettrup, M., S. Khan, K. Schwarz, and G. Schmidtke. 2001. Interferon-γ inducible exchanges of 20S proteasome active site subunits: why? Biochimie 83:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groll, M., L. Ditzel, J. Löwe, D. Stock, M. Bochtler, H. D. Bartunik, and R. Huber. 1997. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 386:463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegerl, R., G. Pfeifer, G. Pühler, B. Dahlmann, and W. Baumeister. 1991. The three-dimensional structure of proteasomes from Thermoplasma acidophilum as determined by electron microscopy using random conical tilting. FEBS Lett. 283:117-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes, M., F. Pfeifer, and M. Dyall-Smith. 1994. Improved shuttle vectors for Haloferax volcanii including a dual-resistance plasmid. Gene 146:117-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jolley, K. A., R. J. Russell, D. W. Hough, and M. J. Danson. 1997. Site-directed mutagenesis and halophilicity of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. Eur. J. Biochem. 248:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kisselev, A. F., T. N. Akopian, K. M. Woo, and A. L. Goldberg. 1999. The sizes of peptides generated from protein by mammalian 26 and 20 S proteasomes. Implications for understanding the degradative mechanism and antigen presentation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3363-3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Löwe, J., D. Stock, B. Jap, P. Zwickl, W. Baumeister, and R. Huber. 1995. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 Å resolution. Science 268:533-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maupin-Furlow, J. A., H. C. Aldrich, and J. G. Ferry. 1998. Biochemical characterization of the 20S proteasome from the methanoarchaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. J. Bacteriol. 180:1480-1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maupin-Furlow, J. A., S. J. Kaczowka, M. S. Ou, and H. L. Wilson. 2001. Archaeal proteasomes: proteolytic nanocompartments of the cell. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 50:279-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price, L. B., and R. F. Shand. 2000. Halocin S8: a 36-amino-acid microhalocin from the haloarchaeal strain S8a. J. Bacteriol. 182:4951-4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruepp, A., and J. Soppa. 1996. Fermentative arginine degradation in Halobacterium salinarium (formerly Halobacterium halobium): genes, gene products, and transcripts of the arcRACB gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 178:4942-4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seemüller, E., A. Lupas, D. Stock, J. Löwe, R. Huber, and W. Baumeister. 1995. Proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum: a threonine protease. Science 268:579-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenzel, T., and W. Baumeister. 1995. Conformational constraints in protein degradation by the 20S proteasome. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson, H. L., H. C. Aldrich, and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 1999. Halophilic 20S proteasomes of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii: purification, characterization, and gene sequence analysis. J. Bacteriol. 181:5814-5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson, H. L., M. S. Ou, H. C. Aldrich, and J. A. Maupin-Furlow. 2000. Biochemical and physical properties of the Methanococcus jannaschii 20S proteasome and PAN, a homolog of the ATPase (Rpt) subunits of the eucaryal 26S proteasome. J. Bacteriol. 182:1680-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao, Y., C. R. Toth, L. Huang, M. L. Wong, P. Dias, A. L. Burlingame, P. Coffino, and C. C. Wang. 1999. α5 subunit in Trypanosoma brucei proteasome can self-assemble to form a cylinder of four stacked heptamer rings. Biochem. J. 344:349-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zühl, F., T. Tamura, I. Dolenc, Z. Cejka, I. Nagy, R. De Mot, and W. Baumeister. 1997. Subunit topology of the Rhodococcus proteasome. FEBS Lett. 400:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zwickl, P., W. Baumeister, and A. Steven. 2000. Dis-assembly lines: the proteasome and related ATPase-assisted proteases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:242-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwickl, P., J. Kleinz, and W. Baumeister. 1994. Critical elements in proteasome assembly. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1:765-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zwickl, P., D. Ng, K. M. Woo, H.-P. Klenk, and A. L. Goldberg. 1999. An archaebacterial ATPase, homologous to ATPases in the eukaryotic 26S proteasome, activates protein breakdown by 20S proteasomes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26008-26014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]