Abstract

Glanders is a debilitating disease with no vaccine available. Murine monoclonal antibodies were produced against Burkholderia mallei, the etiologic agent of glanders, and were shown to be effective in passively protecting mice against a lethal aerosol challenge. The antibodies appeared to target lipopolysaccharide. Humoral antibodies may be important for immune protection against B. mallei infection.

Glanders, a disease caused by the microorganism Burkholderia mallei, was originally described around 425 B.C. and has been a world problem throughout most of recorded history. Humans can acquire the disease from infected animals by inhalation of the organism or through breaks in the skin. Human disease has been described as “loathsome” (15) and is characterized by purulent abscesses in infected tissues and organs (12). While B. mallei has seemingly been eradicated from many parts of the world today, its classification as a category B biothreat agent suggests that the microorganism could have a significant negative worldwide impact on human health. No vaccines against glanders exist, and current diagnostic tests cannot discriminate between infections caused by B. mallei and those caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, another category B pathogen (8). Antibiotic therapy is usually successful with timely diagnosis of the disease.

The relative importance of humoral antibodies and cell-mediated immune responses in glanders immunity remains to be elucidated. Attempts to passively transfer immunity with immune serum were unsuccessful (10, 17). Published reports appear to suggest a greater role for cell-mediated immunity than humoral immunity in the limitation of the early spread of B. mallei in the host (5, 6). Irradiated B. mallei induced a Th1- and Th2-like cytokine response and a Th2-like subclass immunoglobulin response in BALB/c mice (1). Interleukin-12 (IL-12) has been shown to enhance protective immunity against glanders. Vaccinating mice with irradiated B. mallei plus IL-12, but not irradiated B. mallei alone, appears to induce partial protective immunity against a lethal subcutaneous challenge with B. mallei (K. Amemiya, personal communication). Injecting plasmid DNA encoding IL-12 in mice to induce in vivo expression of the cytokine resulted in a significant protection against aerosol infection with B. mallei (R. Ulrich, personal communication). An attenuated branched-chain amino acid auxotroph mutant of B. mallei was recently shown to partially protect against aerosol infection in mice (16).

In an attempt to generate specific antibodies that could be useful in the specific diagnosis of glanders and in prevention of disease, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were generated in BALB/c mice. In determinations of antibody specificity or efficacy against infection, results were evaluated for statistical significance by linear regression analysis or by analysis of variance. Survival distributions were compared by Kaplan-Meier methods. All tests were at the 95% confidence level (two tailed) (14).

To generate monoclonal antibodies, mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 100 μg of irradiation-killed mid-log-phase B. mallei China 7 strain (ATCC 23344) cells and given a second injection 14 days later. Three days after the booster injection, a splenocyte suspension was prepared from the mouse with the highest enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay titer against B. mallei and fused with the murine myeloma cell line P3X63-Ag8.653 (7). Primary hybridoma culture supernatants were screened for antibody activity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with irradiated B. mallei- or B. pseudomallei-coated microtiter wells, and B. mallei-positive hybridomas were subcloned by limiting dilution. Thirty-two clones reacted with B. mallei antigens and were selected for further specificity screening (data not shown). Of these, four anti-B. mallei clones were finally selected, based on their strong reactivity with B. mallei and absence of reactivity with the closely related B. pseudomallei (8). Antibodies were purified by protein A chromatography; purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Culture supernatants from the four selected hybridomas, designated 1G2-1D3, 1G3-1, 9C1-2, and 8G3-1B11, reacted with B. mallei even at high dilutions of culture supernatants tested (Table 1). At each dilution tested, absorbencies of microtiter wells coated with B. mallei antigens were significantly greater (P < 0.003) than absorbencies of microtiter wells coated with B. pseudomallei antigens.

TABLE 1.

Specificity of anti-B. mallei monoclonal antibodies

| MAb | Isotype | Absorbance at a hybridoma culture supernatant dilution of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1,024 | 2,084 | ||

| 8G3-1B11 | IgG2a | 1.40a | 1.12 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.18 |

| 0.15b | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| 9C1-2 | IgG2b | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.49 |

| 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.16 | ||

| 1G2-1D3 | IgG2a | 1.17 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| 1G3-1 | IgG2a | 1.39 | 1.29 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.38 |

| 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | ||

Absorbance obtained with microtiter wells coated with B. mallei antigens.

Absorbance obtained with microtiter wells coated with B. pseudomallei antigens.

To determine the ability of the anti-B. mallei MAbs to specifically capture B. mallei antigens in solution, B. mallei or B. pseudomallei cell lysates were added to microtiter wells precoated with individual anti-B. mallei MAb. Antigen capture was detected by adding a heterologous anti-B. mallei MAb conjugated to biotin (Table 2). All four anti-B. mallei MAbs were capable of capturing B. mallei, but not B. pseudomallei, antigens in solution (P < 0.0001). The negative control MAb termed F1-04-A-G1, specific for the F1 capsular antigen of Yersinia pestis (2), did not bind to either of the two Burkholderia cell lysates (P > 0.05). The ability of the MAbs to specifically recognize B. mallei and not the closely related B. pseudomallei antigens in solid phase, as well as in solution, suggests their potential value as specific diagnostic tools in differentiating glanders and melioidosis in clinical conditions.

TABLE 2.

Specific antigen capture by anti-B. mallei monoclonal antibodies

| Monoclonal antibody coat | Bacterial antigen addeda (μg/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Burkholderia mallei

|

Burkholderia pseudomallei

|

|||||

| 5.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 | |

| 8G3-1B11 | 0.450b | 0.686 | 0.827 | 0.120 | 0.127 | 0.113 |

| 1G2-1D3 | 0.349 | 0.424 | 0.603 | 0.137 | 0.141 | 0.140 |

| 1G3-1 | 0.351 | 0.450 | 0.698 | 0.110 | 0.116 | 0.118 |

| 9C1-2 | 0.481 | 0.663 | 0.910 | 0.136 | 0.106 | 0.099 |

| F1-04-A-G1 | 0.110 | 0.112 | 0.178 | 0.112 | 0.118 | 0.145 |

B. mallei or B. pseudomallei antigens (100 μl) were added to microtiter wells precoated with various anti-B. mallei MAbs (50 μl of 20 μg/ml).

Average absorbance of triplicate determinations.

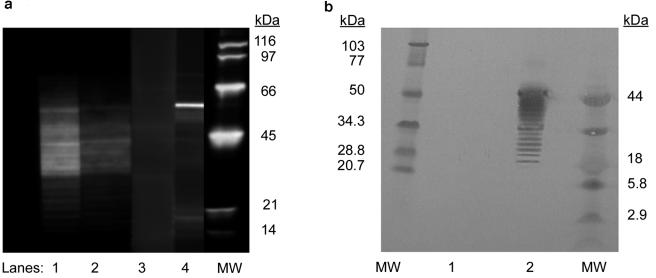

We then determined the antigenic specificity of the four anti-B. mallei MAbs by immunoblot analysis of B. mallei separated by SDS-PAGE with 10 to 20% precast Tricine gels (Invitrogen) (11). The immunoblot reactivity of two representative MAbs (8G3-1B11 and 1G2-1D3) is shown in Fig. 1a. Both MAbs reacted with B. mallei antigens characterized by a typical LPS ladder-banding pattern, ranging from approximately 20 kDa to 50 kDa in molecular mass (Fig. 1a, lanes 1 and 2). No reactivity was detected in immunoblot analyses of irradiated B. pseudomallei separated by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Pretreating the irradiated B. mallei bacterial lysate with proteinase K did not abolish nor alter the immunoblot reactivity or the typical ladder-banding pattern, further supporting the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) nature of the antigens recognized (Fig. 1b, lane 2). Again, no immunoblot reactivity was evident with irradiated B. pseudomallei bacterial lysate (Fig. 1b, lane 1). Ample experimental evidence exists to suggest an important role of bacterial capsules in the virulence of both gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens. The capsular exopolysaccharide of B. mallei and B. pseudomallei was recently demonstrated to play a vital role in enhancing the virulence of the bacteria (4, 13). Whether or not the anti-B. mallei MAbs described herein are specific for LPS associated with the bacterial capsule remains to be determined.

FIG. 1.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of two representative anti-B. mallei MAbs. Lane 1, 8G3-1B11 MAb; lane 2, 1G2-1D3; lane 3, preimmune negative mouse serum control (1:1,000); lane 4, positive anti-B. mallei mouse serum (1:1,000); MW, molecular mass standards. (b) Immunoblot analysis of proteinase K-treated B. mallei and B. pseudomallei. MW, high-molecular-mass standards (103 kDa, 77 kDa, 50 kDa, 34.3 kDa, 28.8 kDa, and 20.7 kDa); lane 1, proteinase K-treated B. pseudomallei; lane 2, proteinase K-treated B. mallei; MW, low-molecular-mass standards (44 kDa, 18 kDa, 5.8 kDa, and 2.9 kDa).

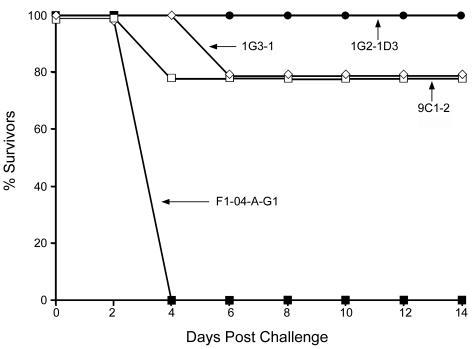

We were interested in determining whether our MAbs could passively protect mice against a lethal aerosol challenge of B. mallei. Groups of six BALB/c mice each were injected i.p. with 1.0-mg/mouse of purified anti-B. mallei MAbs and challenged by whole-body aerosol 18 h thereafter with 20 50% lethal doses (LD50; 1.9 ×104 CFU) of an overnight culture in mid-log phase of B. mallei, strain China 7 (ATCC 23344). Negative control groups were injected with either Hanks' balanced salt solution or MAb F1-04-A-G1 specific for the F1 antigen of Y. pestis. After challenge, the mice were observed daily, and mortalities and the mean time to death were recorded. At the end of the experiment, all survivors were humanely killed. Immunization and challenge experiments were conducted in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) and BSL4 environments, respectively. As expected, the negative control F1-04-A-G1 did not protect the mice from the challenge (Fig. 2). Conversely, the anti-B. mallei MAbs provided significant protection. Monoclonal antibody 1G2-1D3 completely protected the mice against aerosol challenge (100% survival). Significant protection was also observed in mice treated with MAbs 9C1-2 and 1G3-1 (83% survival). All protected mice survived up to 14 days postchallenge, at which time the experiment was terminated. There were no significant differences in the ability of the MAbs to protect from death (P > 0.05). All MAbs were able to significantly protect against death (P < 0.01), compared to the irrelevant MAb control (F1-04-A-G1).

FIG. 2.

Passive protection by anti-B. mallei MAbs against a lethal aerosol challenge of B. mallei. Groups of six mice each were treated i.p. with anti-B. mallei MAbs (□, 9C1-2; •, 1G2-1D3, ⋄, 1G3-1) or a negative control anti-F1 MAb (▪, F1-04-A-G1) 18 h before an aerosol challenge with 20 LD50 (1 LD50 = 1,000 CFU) of B. mallei strain China 7 (ATCC 23344).

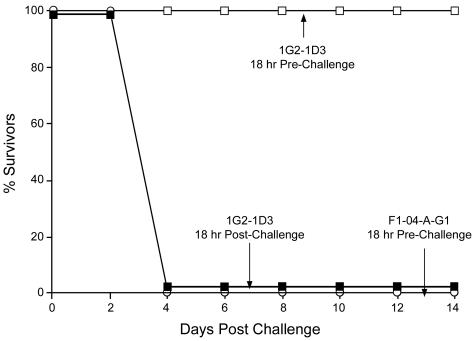

To assess the immunotherapeutic potential of the anti-B. mallei MAbs, groups of six mice each were treated with 1 mg of 1G2-1D3 anti-B. mallei MAb either 18 h before or 18 h after aerosol challenge. Treatment with 1G2-1D3 MAb 18 h before challenge again completely protected the mice against a lethal B. mallei aerosol challenge (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). However, this anti-B. mallei MAb administered 18 h postchallenge was ineffective in providing protection (P > 0.05). All mice in this group, as well as those in the negative MAb (F1-04-A-G1) control group, died 4 days postchallenge.

FIG. 3.

Lack of passive protection by anti-B. mallei MAb 1G2-1D3 given postchallenge. Groups of six mice each were treated i.p. per mouse with 1 mg of either 1G2-1D3 anti-B. mallei MAb (□) or F1-04-A-G1 anti-F1 negative control MAb (○) 18 h before an aerosol challenge with 20 LD50 of B. mallei strain China 7 (ATCC 23344) or challenged and then given per mouse 1 mg of 1G2-1D3 MAb 18 h postchallenge (▪).

This represents, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of passive protection against B. mallei infection in a murine model of aerosolized glanders by MAbs. Note that although significant passive protection was achieved, the spleens of all surviving mice killed at the end of the experiment contained significant numbers of B. mallei cells. Thus, the immune protection mediated by anti-B. mallei MAbs was not sterile but appeared to result from an antibody-induced reduction of the number of infecting pathogens below the lethal threshold. Whether antibody administered <18 h postchallenge would provide protection remains to be determined. It is clear that antibody-mediated protection is most effective during the initial phase of infection, presumably by clearing the pathogens from the circulation and/or limiting or reducing the number of pathogens being internalized by the primary host target cells, the macrophages. A likely explanation for the lack of protection by MAb treatment administered 18 h postchallenge is that once phagocytosed, the intracellular pathogens are protected from and therefore less affected by circulating antibodies, at least at the dose of antibodies (1.0 mg/mouse) used in the experiment. However, our results using an in vitro system of B. mallei infection of J774 murine macrophages suggest that the number of intracellular pathogens decreased in infected cells cultured in the presence of anti-B. mallei MAbs and complement, compared to that in infected cells cultured in the absence of antibodies and complement (unpublished observations). Therefore, it is conceivable that circulating antibodies at sufficient concentrations could have a bacteriostatic or bactericidal effect on intracellular pathogens in vivo. Similar passive protection against i.p. B. pseudomallei infection was previously reported. Polyclonal antisera specific for the polysaccharide of P. pseudomallei LPS were shown to passively protect against an i.p. P. pseudomallei infection in a diabetic rat model of melioidosis (3). Likewise, murine MAbs specific for B. pseudomallei polysaccharide passively protected mice challenged i.p. with B. pseudomallei (9). Thus, the presence of circulating antibodies at the initial stages of infection may contribute to protective immunity against glanders and melioidosis, two clinical conditions caused by the phylogenetically closely related B. mallei and B. pseudomallei, respectively (8). However, as in most diseases caused by intracellular pathogens, in addition to specific humoral immunity, a robust and specific cell-mediated immunity would in all likelihood be necessary for eliminating infected cells and controlling pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency's Joint Science and Technology Office (JSTO) for Chemical and Biological Defense, project number A2_X003_04_RD_B.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

The research described in the manuscript was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statues and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 1996. The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Tran C. Chanh—gifted researcher, caring mentor, and friend.

We thank R. Ulrich and K. Amemiya for critically reading the manuscript and S. Guest for his technical support in producing and maintaining the hybridoma cultures.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

REFERENCES

- 1.Amemiya, K., G. V. Bush, D. DeShazer, and D. M. Waag. 2002. Nonviable Burkholderia mallei induces a mixed Th1- and Th2-like cytokine response in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 70:2319-2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, G. W., Jr., P. L. Worsham, C. R. Bolt, G. P. Andrews, S. L. Welkos, A. M. Friedlander, and J. P. Burans. 1997. Protection of mice from fatal bubonic and pneumonic plague by passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies against the F1 protein of Yersinia pestis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:471-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan, L. E., S. Wong, D. E. Woods, D. A. B. Dance, and W. Chaowagul. 1994. Passive protection of diabetic rats with antisera specific for the polysaccharide portion of the lipopolysaccharide isolated from P. pseudomallei. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 5:170-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeShazer, D., D. M. Waag, D. L. Fritz, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Identification of a Burkholderia mallei polysaccharide gene cluster by subtractive hybridization and demonstration that the encoded capsule is an essential virulence determinant. Microb. Pathog. 30:253-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diadishchev, N. R., A. A. Vorob'ev, and S. B. Zakharov. 1997. The pathomorphology and pathogenesis of glanders in laboratory animals. Zh. Mikrobiol Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1997:60-64. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diadishchev, N. R., A. A. Vorob'eva, and S. B. Zakharov. 1997. The transfer of antibacterial resistance to recipients highly sensitive to glanders. Zh. Mikrobiol Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1997:81-84. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gefter, M. L., D. H. Margulies, and M. D. Scharff. 1977. A simple method for the polyethylene glycol-promoted hybridization of mouse myeloma cells. Somatic Cell Genet. 3:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godoy, D., G. Randle, A. J. Simpson, D. M. Aanensen, T. L. Pitt, R. Kinoshita, and B. G. Spratt. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing and evolutionary relationships among the causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2068-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones, S. M., J. F. Ellis, P. Russell, K. F. Griffin, and P. C. Oyston. 2002. Passive protection against Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in mice by monoclonal antibodies against capsular polysaccharide, lipopolysaccharide or proteins. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:1055-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovalev, G. K. 1971. Glanders. Zh. Mikrobiol Epidemiol. Immunobiol 48:63-70. (In Russian.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehavi, O., O. Aizenstien, L. H. Katz, and A. Hourvitz. 2002. Glanders—a potential disease for biological warfare in humans and animals. Harefuah 141(Special no.):88-91. (In Hebrew.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reckseidler, S. L., D. DeShazer, P. A. Sokol, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Detection of bacterial virulence genes by subtractive hybridization: identification of capsular polysaccharide of Burkholderia pseudomallei as a major virulence determinant. Infect. Immun. 69:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAS Institute. 2004. SAS 9.1. SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

- 15.Steele, J. H. 1979. Glanders, p. 339-362. In J. H. Steele (ed.), CRC handbook series in zoonoses. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 16.Ulrich, R. L., K. Amemiya, D. M. Waag, C. J. Roy, and D. DeShazer. 2005. Aerogenic vaccination with a Burkholderia mallei auxotroph protects against aerosol-initiated glanders in mice. Vaccine 23:1986-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vyshelesskii, S. N. 1974. Glanders (Equinia). Tr. Vsesoiuzyni Inst. Eksp. Veterinari. 42:67-92. (In Russian.) [Google Scholar]