Abstract

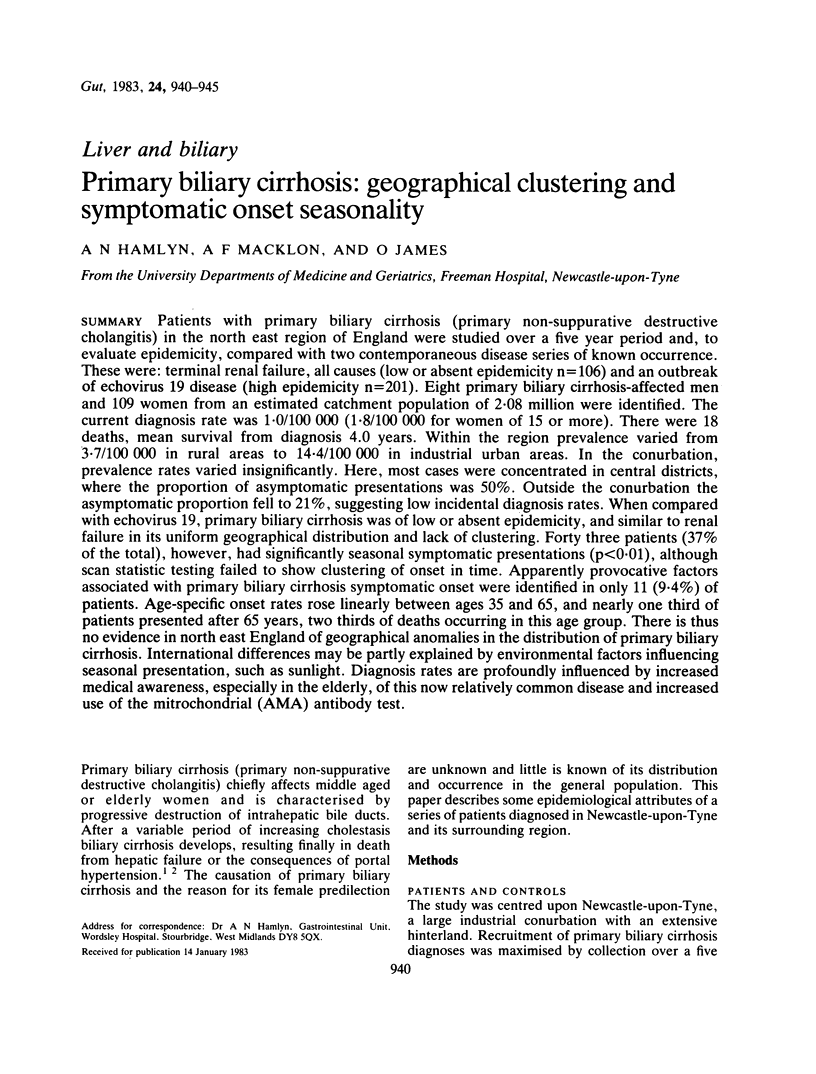

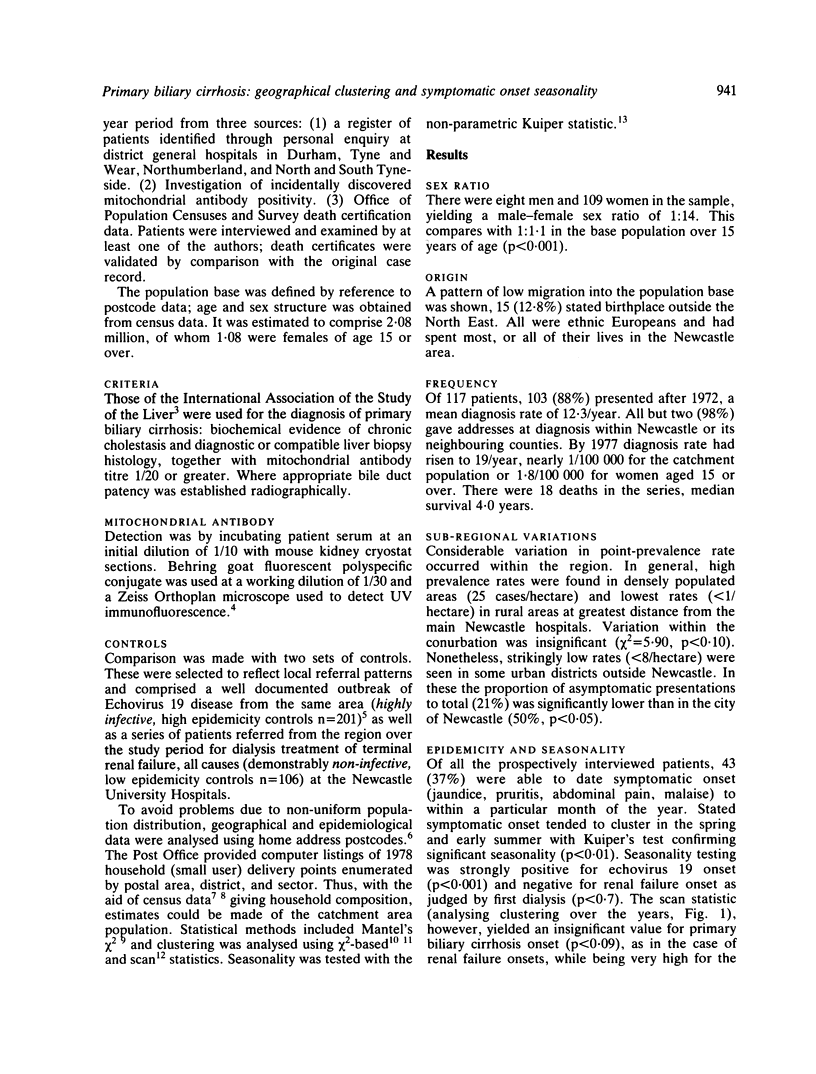

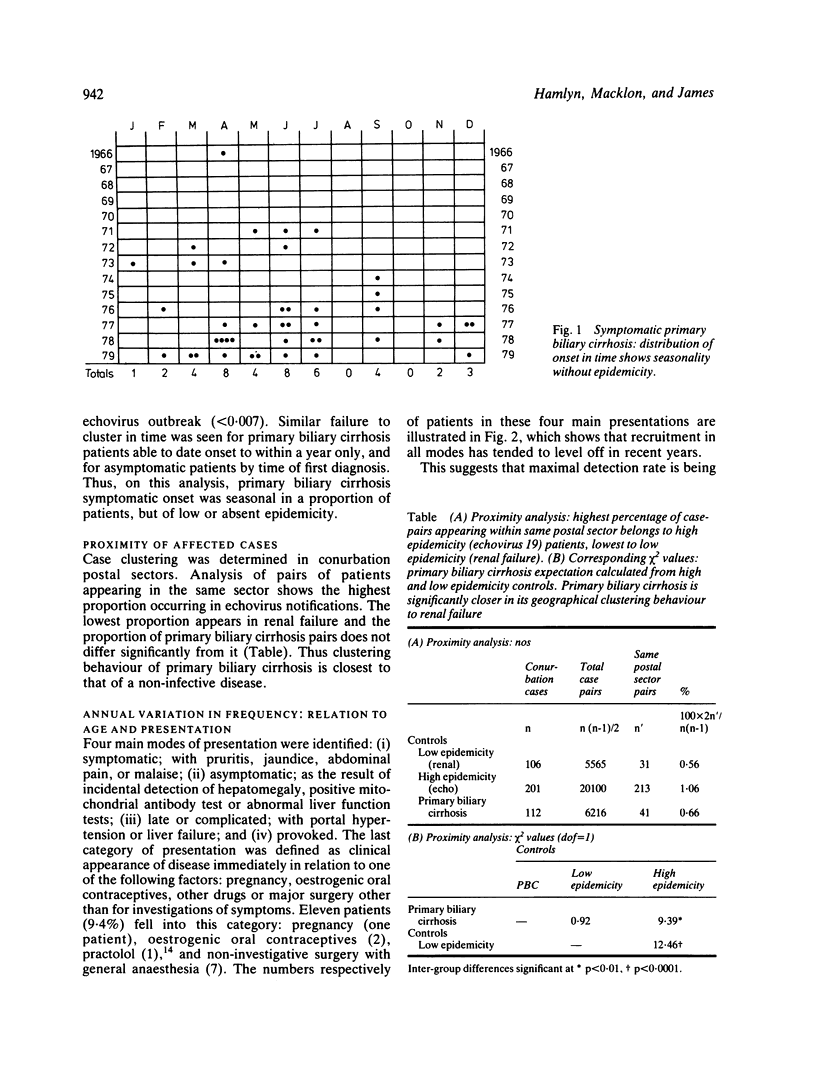

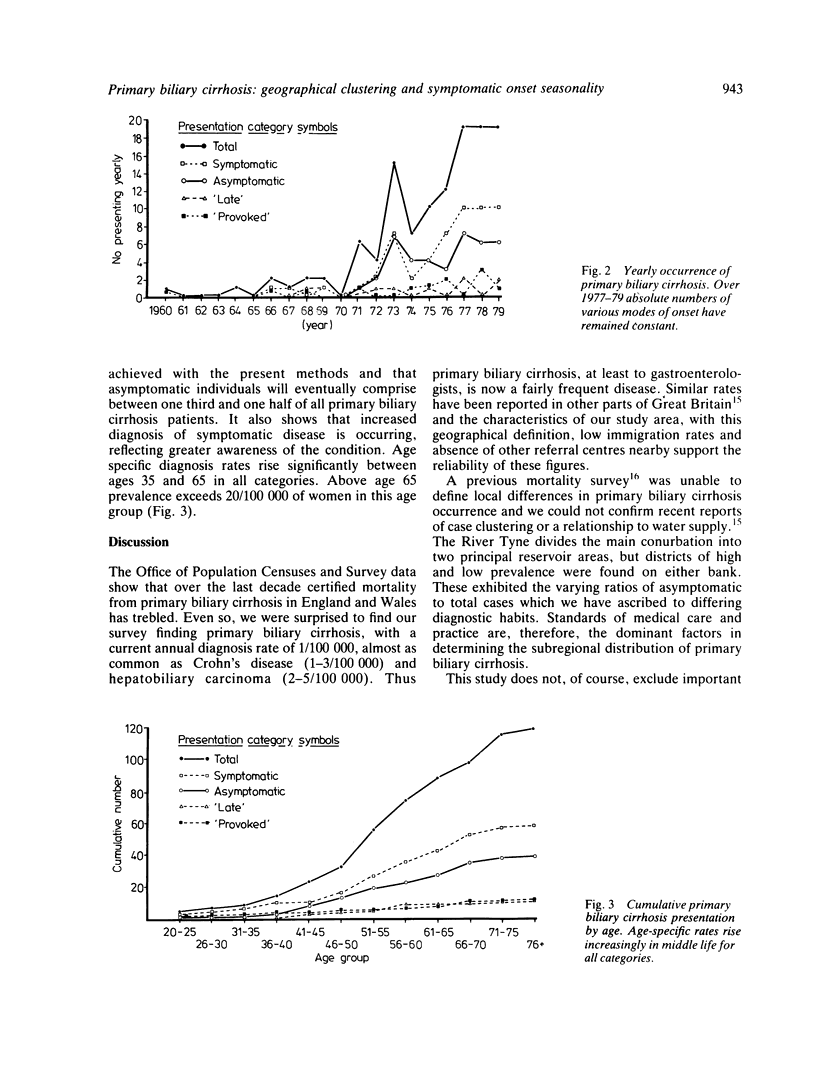

Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (primary non-suppurative destructive cholangitis) in the north east region of England were studied over a five year period and, to evaluate epidemicity, compared with two contemporaneous disease series of known occurrence. These were: terminal renal failure, all causes (low or absent epidemicity n = 106) and an outbreak of echovirus 19 disease (high epidemicity n = 201). Eight primary biliary cirrhosis-affected men and 109 women from an estimated catchment population of 2.08 million were identified. The current diagnosis rate was 1.0/100 000 (1.8/100 000 for women of 15 or more). There were 18 deaths, mean survival from diagnosis 4.0 years. Within the region prevalence varied from 3.7/100 000 in rural areas to 14.4/100 000 in industrial urban areas. In the conurbation, prevalence rates varied insignificantly. Here, most cases were concentrated in central districts, where the proportion of asymptomatic presentations was 50%. Outside the conurbation the asymptomatic proportion fell to 21%, suggesting low incidental diagnosis rates. When compared with echovirus 19, primary biliary cirrhosis was of low or absent epidemicity, and similar to renal failure in its uniform geographical distribution and lack of clustering. Forty three patients (37% of the total), however, had significantly seasonal symptomatic presentations (p less than 0.01), although scan statistic testing failed to show clustering of onset in time. Apparently provocative factors associated with primary biliary cirrhosis symptomatic onset were identified in only 11 (9.4%) of patients. Age-specific onset rates rose linearly between ages 35 and 65, and nearly one third of patients presented after 65 years, two thirds of deaths occurring in this age group. There is thus no evidence in north east England of geographical anomalies in the distribution of primary biliary cirrhosis. International differences may be partly explained by environmental factors influencing seasonal presentation, such as sunlight. Diagnosis rates are profoundly influenced by increased medical awareness, especially in the elderly, of this now relatively common disease and increased use of the mitochondrial (AMA) antibody test.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- AHRENS E. H., Jr, PAYNE M. A., KUNKEL H. G., EISENMENGER W. J., BLONDHEIM S. H. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1950 Dec;29(4):299–364. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195012000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. J., Lesna M., Hamlyn A. N., Record C. O. Primary biliary cirrhosis after long-term practolol administration. Br Med J. 1978 Jun 17;1(6127):1591–1591. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6127.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codd A. A., Hale J. H. Epidemic of echovirus 19 in the north-east of England. J Hyg (Lond) 1976 Apr;76(2):307–317. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400055200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniach D., Walker G. Mitochondrial antibodies (AMA). Gut. 1974 Aug;15(8):664–668. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.8.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman L. S. The use of a Kolmogorov--Smirnov type statistic in testing hypotheses about seasonal variation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1979 Sep;33(3):223–228. doi: 10.1136/jech.33.3.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLIAM A. G., MACMAHON B. Geographic distribution and trends of leukaemia in the United States. Acta Unio Int Contra Cancrum. 1960;16:1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith R. M., Eddleston A. L., Smith M. G., Williams R., McSween R. N., Watkinson G., Dick H., Kennedy L. A., Batchelor J. R. Histocompatibility antigens in active chronic hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis. Br Med J. 1974 Sep 7;3(5931):604–605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5931.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlyn A. N., Adams D., Sherlock S. Primary or secondary sicca complex? Investigation in primary biliary cirrhosis by histocompatibility testing. Br Med J. 1980 Aug 9;281(6237):425–426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6237.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlyn A. N., Morris J. S., Sherlock S. ABO blood groups, Rhesus negativity, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 1974 Jun;15(6):480–481. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.6.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlyn A. N., Sherlock S. The epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis: a survey of mortality in England and Wales. Gut. 1974 Jun;15(6):473–479. doi: 10.1136/gut.15.6.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNOX G. DETECTION OF LOW INTENSITY EPIDEMICITY: APPLICATION TO CLEFT LIP AND PALATE. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1963 Jul;17:121–127. doi: 10.1136/jech.17.3.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNOX G. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD LEUKAEMIA IN NORTHUMBERLAND AND DURHAM. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1964 Jan;18:17–24. doi: 10.1136/jech.18.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock S., Scheuer P. J. The presentation and diagnosis of 100 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1973 Sep 27;289(13):674–678. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197309272891306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triger D. R. Primary biliary cirrhosis: an epidemiological study. Br Med J. 1980 Sep 20;281(6243):772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6243.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenstein S. A test for detection of clustering over time. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Mar;111(3):367–372. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]