Traditionally wet-to-dry gauze has been used to dress wounds. Dressings that create and maintain a moist environment, however, are now considered to provide the optimal conditions for wound healing. Moisture under occlusive dressings not only increases the rate of epithelialisation but also promotes healing through moisture itself and the presence initially of a low oxygen tension (promoting the inflammatory phase). Gauze does not exhibit these properties; it may be disruptive to the healing wound as it dries and cause tissue damage when it is removed. It is not now widely used in the United Kingdom.

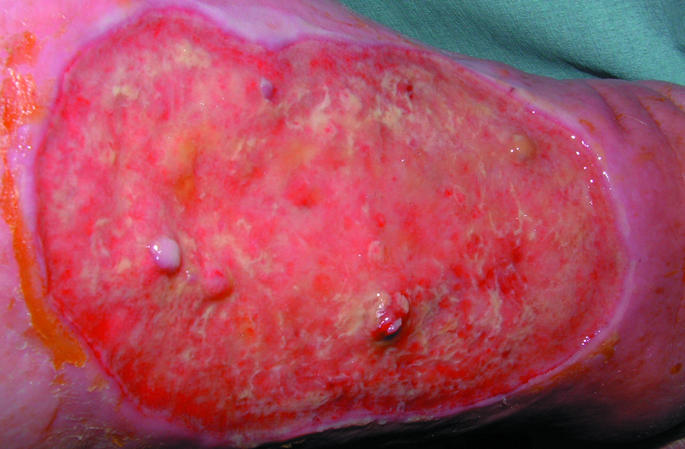

Figure 1.

Left: Healthy venous leg ulcer suitable for dressing with low adherent dressing. Right: Wound suitable for dressing with semipermeable film

Table 1.

Characteristics of the ideal dressing

| • Capable of maintaining a high humidity at the wound site while removing excess exudate |

| • Free of particles and toxic wound contaminants |

| • Non-toxic and non-allergenic |

| • Capable of protecting the wound from further trauma |

| • Can be removed without causing trauma to the wound |

| • Impermeable to bacteria |

| • Thermally insulating |

| • Will allow gaseous exchange |

| • Comfortable and conformable |

| • Require only infrequent changes |

| • Cost effective |

| • Long shelf life |

Occlusive dressings are thought to increase cell proliferation and activity by retaining an optimum level of wound exudate, which contains vital proteins and cytokines produced in response to injury. These facilitate autolytic debridement of the wound and promote healing. Concerns of increased risk of infection under occlusive dressings have not been substantiated in clinical trials. This article describes wound dressings currently available in the UK.

Figure 2.

Venous leg ulcer suitable for dressing with hydrocolloid

Table 2.

Low adherent dressings—suitable for use on flat, shallow wounds with low exudates

| Tulles—Bactigras, Jelonet, Paranet, Paratulle, Tullegras, Unitulle, Urgotul |

| Textiles—Atrauman, Mepilex, Mepitel, NA Dressing, NA Ultra, Tegapore, Tricotex |

Low adherent dressings

Low adherent dressings are cheap and widely available. Their major function is to allow exudate to pass through into a secondary dressing while maintaining a moist wound bed.

Most are manufactured in the form of tulles, which are open weave cloth soaked in soft paraffin or chlorhexidine; textiles; or multilayered or perforated plastic films.

They are designed to reduce adherence at the wound bed and are particularly useful for patients with sensitive or fragile skin.

Semipermeable films

Semipermeable films were one of the first major advances in wound management and heralded a major change in the way wounds were managed. They consist of sterile plastic sheets of polyurethane coated with hypoallergenic acrylic adhesive and are used mainly as a transparent primary wound cover.

Although they are impermeable to fluids and bacteria, they are permeable to air and water vapour, the control of which is dependent on the moisture and vapour transmission rate, which varies depending on the brand. It is through this mechanism that this dressing creates a moist wound environment.

Films are very flexible and are good for wounds on “difficult” anatomical sites—for example, over joints. They are unable to cope with large amounts of exudate, however, and may cause maceration of the skin surrounding the wound bed if they are used injudiciously.

Table 3.

Semipermeable films

| Examples include Bioclusive, Mefilm, OpSite Flexigrid,* OpSite Plus, Tegaderm |

| • Suitable for flat, shallow wounds with low to medium exudates |

| • Promote moist environment |

| • Adhere to healthy skin but not to wound |

| • Allow visual checks |

| • May be left in place several days |

| • Useful as secondary dressing |

| • Provide no cushioning |

| • Not for infected or heavily exuding wounds |

Not available on prescription in UK primary care.

Hydrocolloids

This is the ninth in a series of 12 articles

Modern dressing technology is based on the principle of creating and maintaining a moist wound environment

Sodium carboxymethylcellulose, gelatin, pectin, elastomers, and adhesives are bonded to a carrier of semipermeable film or a foam sheet to produce a flat, occlusive, adhesive dressing that forms a gel on the wound surface, promoting moist wound healing. Cross linkage of the materials used influences the viscosity of the gel under the dressing. This gel, which may be yellow and malodorous, may be mistaken for infection by the unwary. Hydrocolloids are virtually impermeable to water vapour and air and can be used to rehydrate dry necrotic eschar and promote autolytic debridement. They are reported to reduce wound pain, and their barrier properties allow the patient to bathe or shower and continue with normal daily activities without disturbing or risking contamination of the wound. Caution should be exercised when using hydrocolloids for wounds that require frequent inspection—for example, for diabetic foot ulcers.

Figure 3.

Foot wound complicated by heterotopic calcification suitable for dressing with hydrofibres

Table 4.

Hydrocolloid dressings (including hydrofibres)

| Type of dressing | Uses |

|---|---|

| Hydrocolloid sheets: Alione, CombiDERM, CombiDERM N, Comfeel,* Comfeel Plus, Cutinova Thin,* DuoDERM Extra Thin,* Granuflex,* Tegasorb, Tegasorb Thin | Cavity or flat shallow wounds with low to medium exudate; absorbent; conformable; good in “difficult” areas—heel, elbow, sacrum |

| Hydrocolloid paste: GranuGel Paste* | May be left in place for several days; useful debriding agent; may cause maceration |

| Hydrofibre: Aquacel (Hydrofibre), Versiva | Useful in flat wounds, cavities, sinuses, undermining wounds; medium to high exudate wounds; highly absorbent; non-adherent; may be left in place for several days; needs secondary dressing |

Not available on prescription in UK primary care.

Hydrocolloid fibres are now available in the form of a hydrophilic, non-woven flat sheet, referred to as hydrofibre dressings. On contact with exudate, fibres are converted from a dry dressing to a soft coherent gel sheet, making them suitable for wounds with a large amount of exudate.

Figure 4.

Dry, sloughy leg wound suitable for dressing with hydrogel

Table 5.

Hydrogels

| Examples include Aquaform, Intrasite, GranuGel, Nu-Gel, Purilon, Sterigel |

| • Supply moisture to wounds with low to medium exudate |

| • Suitable for sloughy or necrotic wounds |

| • Useful in flat wounds, cavities, and sinuses |

| • May be left in place several days |

| • Need secondary dressing |

| • May cause maceration |

Hydrogels

Hydrogels consist of a matrix of insoluble polymers with up to 96% water content enabling them to donate water molecules to the wound surface and to maintain a moist environment at the wound bed. As the polymers are only partially hydrated, hydrogels have the ability to absorb a degree of wound exudate, the amount varying between different brands. They transmit moisture vapour and oxygen, but their bacterial and fluid permeability is dependent on the type of secondary dressing used.

Figure 5.

Diabetic foot ulcer with maceration to surrounding skin suitable for dressing with alginate

Hydrogels promote wound debridement by rehydration of non-viable tissue, thus facilitating the process of natural autolysis. Amorphous hydrogels are the most commonly used and are thick, viscous gels.

Hydrogels are considered to be a standard form of management for sloughy or necrotic wounds. They are not indicated for wounds producing high levels of exudate or where there is evidence of gangrenous tissue, which should be kept dry to reduce the risk of infection.

Alginates

Alginates are produced from the naturally occurring calcium and sodium salts of alginic acid found in a family of brown seaweed (Phaeophyceae). They generally fall into one of two kinds: those containing 100% calcium alginate or those that contain a combination of calcium with sodium alginate, usually in a ratio of 80:20.

Alginates are rich in either mannuronic acid or guluronic acid, the relative amount of each influencing the amount of exudate absorbed and the shape the dressing will retain. Alginates partly dissolve on contact with wound fluid to form a hydrophilic gel as a result of the exchange of sodium ions in wound fluid for calcium ions in the dressing. Those high in mannuronic acid (such as Kaltostat) can be washed off the wound easily with saline, but those high in guluronic acid (such as Sorbsan) tend to retain their basic structure and should be removed from the wound bed in one piece.

Table 6.

Alginates

| Examples include Algisite, Algosteril, Kaltostat,* Melgisorb, SeaSorb, Sorbsan, Sorbsan SA,* Tegagen, Urgosorb |

| • Useful in cavities and sinuses, and for undermining wounds |

| • For all wound types with high exudates |

| • Highly absorbent |

| • Need secondary dressing |

| • Need to be changed daily |

Not available on prescription in UK primary care

Hydrocolloid fibres (hydrofibres) are often used on wounds where, traditionally, alginates have been used

Alginates can absorb 15 to 20 times their weight of fluid, making them suitable for highly exuding wounds. They should not be used, however, on wounds with little or no exudate as they will adhere to the healing wound surface, causing pain and damaging healthy tissue on removal.

Figure 6.

Venous leg ulceration in background of chronic oedema suitable for dressing with foam

Foam dressings

Foam dressings are manufactured as either a polyurethane or silicone foam. They transmit moisture vapour and oxygen and provide thermal insulation to the wound bed. Polyurethane foams consist of two or three layers, including a hydrophilic wound contact surface and a hydrophobic backing, making them highly absorbent. They facilitate uniform dispersion of exudate throughout the absorbent layer and prevent exterior leakage (strike-through) due to the presence of a semipermeable backing.

Figure 7.

Top left: Sloughy, infected arterial ulcer suitable for dressing with compound antimicrobial dressing (silver or iodine based). Top right: Gangrenous foot suitable for dressing with antimicrobial iodine impregnated dressing. Left: Malodorous malignant melanoma ulcer suitable for treatment with topical metronidazole

Table 7.

Foam dressings

| Type of dressing | Uses |

|---|---|

| Adhesive sheets: Allevyn Adhesive, Allevyn Lite Island, Allevyn Thin, Allevyn Plus Adhesive, Biatain Adhesive, Lyofoam Extra Adhesive, Tielle Plus, Tielle Lite, Tielle | Flat, shallow wounds (control of exudate depending on type of foam); give degree of cushioning; may be left in place for two to three days Need secondary dressing |

| Non-adherent sheets: Allevyn,* Allevyn Lite, Lyofoam,* Lyofoam Extra* | |

| Allevyn Cavity, Allevyn Plus Cavity, Cavi-Care | Cavity wound with medium to high exudate |

Not available on prescription in UK primary care.

Polyurethane foam dressings are also available as a cavity dressing—small chips of hydrophilic polyurethane foam enclosed in a membrane of perforated polymeric film, giving a loosely filled bag.

Table 8.

Antimicrobial dressings

| For use in all locally infected wounds |

| • Acticoat |

| • Actisorb Silver 200 |

| • Aquacel Ag |

| • Arglaes |

| • Avance |

| • Inadine |

| • Iodoflex |

| • Iodosorb |

| • Metrotop Gel |

Silicone foams consist of a polymer of silicone elastomer derived from two liquids, which, when mixed together, form a foam while expanding to fit the wound shape forming a soft open-cell foam dressing. The major advantage of foam is the ability to contain exudate. In addition, silicone foam dressings protect the area around the wound from further damage.

Antimicrobial dressings

Silver, in ionic or nanocrystalline form, has for many years been used as an antimicrobial agent particularly in the treatment of burns (in the form of silver sulfadiazine cream). The recent development of dressings impregnated with silver has widened its use for many other wound types that are either colonised or infected.

Iodine also has the ability to lower the microbiological load in chronic wounds. Clinically it is mainly used in one of two formats: (a) as povidone-iodine (polyvinylpyrrolidone-iodine complex), an iodophor (a compound of iodine linked to a non-ionic surfactant), which is produced as an impregnated tulle; and (b) as cadexomer iodine (a three dimensional starch lattice containing 0.9% iodine). Cadexomer iodine has good absorptive properties: 1 g of cadexomer iodine can absorb up to 7 ml of fluid. As fluid is absorbed, iodine is slowly released, reducing the bacterial load and also debriding the wound of debris. This mode of action facilitates the delivery of iodine over a prolonged period of time—thus, in theory, maintaining a constant level of iodine in the wound bed.

Caution is required in patients with a thyroid disease owing to possible systemic uptake of iodine. For this reason, thyroid function should be monitored in patients who are treated with iodine dressings.

Metronidazole gel is often used for the control of odour caused by anaerobic bacteria. This is particularly useful in the management of fungating malignant wounds. It may be used alone or as an adjunct to other dressings.

Unwanted effects of dressings

Maceration of the skin surrounding a wound may occur if a dressing with a low absorptive capacity is used on a heavily exuding wound. If the dressing is highly absorptive then more frequent dressing changes may be needed, in addition to investigation and management of the cause of the exudate (such as infection).

The ion exchange properties of some alginates make them useful haemostatic agents, and as such they are particularly useful for postoperative wound packing

Inappropriate use of dressings may lead to unwanted effects

The skin surrounding a highly exuding wound may be further protected through the use of emollients (such as 50:50 mix of white soft paraffin and liquid paraffin) or the application of barrier films (such as Cavilon). Conversely, use of a highly absorptive dressing on a dry wound may lead to disruption of healthy tissue on the wound surface and cause pain when removed.

Figure 8.

Abdominoperineal resection wound treated with vacuum assisted closure. The skin edges are protected with a barrier cream to prevent maceration

Allergic reactions are not uncommon: the dressing should be avoided, and the allergy may need to be treated with potent topical steroids. Tapes used to keep dressings in place are common causes of allergy. Many dressings require secondary dressings—for example, padding on highly exuding wounds—which may make them bulky. Secondary dressings should not be too tight, especially on patients with peripheral vascular disease.

Figure 9.

Left: Allergy to dressing used to treat arterial leg ulceration. Note erythematous skin with sharply demarcated edges corresponding to the shape of the offending dressing. Right: Ulceration over the anterior aspect of the ankle caused by inappropriately tight bandage

Competing interests: For series editors' competing interests, see the first article in this series.

The ABC of wound healing is edited by Joseph E Grey (joseph.grey@cardiffandvale.wales.nhs.uk), consultant physician, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust, Cardiff, and honorary consultant in wound healing at the Wound Healing Research Unit, Cardiff University, and by Keith G Harding, director of the Wound Healing Research Unit, Cardiff University, and professor of rehabilitation medicine (wound healing) at Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust. The series will be published as a book in summer 2006.

Further reading and resources

- • Choucair M, Phillips T. A review of wound healing and dressings material. Skin and Aging 1998;6:(suppl): 37-43. [Google Scholar]

- • Hermans MH, Bolton LL. Air exposure versus occlusion: merits and disadvantages of different dressings. J Wound Care 1993;2: 362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Morgan DA. Wound management products in the drug tariff. Pharmaceutical Journal 1999;263: 820-5. [Google Scholar]

- • Thomas S, Leigh IM. Wound dressings. In: Leaper DJ, Harding KG, eds. Wounds: biology and management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998:166-83.

- • Turner TD. Development of wound management products in chronic wound care. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver G, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic wound care: a clinical source book for healthcare professionals. 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: HMP Communications, 2001.

- • Winter G. Formation of scab and the rate of epithelialisation of superficial wounds in the skin of the young domestic pig. Nature 1962;193: 293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Vermeulen H, Ubbink D, Goossens A, de Vos R, Legemate D. Dressings and topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4): CD003554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]