Abstract

Objective

The clinical usefulness of preoperative localization and intraoperative PTH assay (QPTH) in primary hyperparathyroidism have been established. However, without the use of QPTH, the parathyroidectomy failure rate remains 5% to 10% in large reported series and is probably much higher in the hands of less experienced parathyroid surgeons. Persistent hypercalcemia requires another surgical procedure. The authors compared the outcomes in 50 consecutive patients undergoing more difficult secondary parathyroidectomy with and without the adjunctive support of QPTH.

Methods

Two groups of similar patients underwent reoperative parathyroidectomy for failed surgery or recurrent disease. The successful return to normocalcemia in group I, with QPTH used to localize and confirm complete excision of all hyperfunctioning glands, was compared with group II, who did not have this intraoperative adjunct.

Results

In 31/33 patients in group I, calcium levels returned to normal. With good preoperative localization studies, 17 patients underwent successful straightforward parathyroidectomies as predicted by QPTH. In the other 14 patients, QPTH assay proved extremely beneficial by facilitating localization with differential venous sampling; measuring the increase in hormone secretion after massage of specific areas; recognizing suspicious nonparathyroid tissue excised without a decrease in hormone levels, avoiding frozen-section delay; and correctly identifying the excision of abnormal tissue despite false-positive/false-negative sestamibi scans. In group II, who underwent surgery before QPTH was available, 4 of 17 patients (24%) remained hypercalcemic after extensive reexploration.

Conclusion

With the intraoperative hormone assay used to facilitate localization and confirm excision of all hyperfunctioning tissue, the success rate of reoperative parathyroidectomy has improved from 76% to 94%.

Reoperative parathyroidectomy, for patients remaining hypercalcemic after previous neck exploration or in those in whom recurrent hyperparathyroidism develops years after an initial surgical procedure, is often difficult and unsuccessful. Recent technical advances for the preoperative localization of these hypersecreting parathyroid tumors has improved our ability to find and excise obscure and previously overlooked glands. At present, the most widely used methods for localization are ultrasonography and Tc-99m-sestamibi nuclear scanning. Unfortunately, interpretation using these methods is often unsuccessful or misleading in the postoperative neck, where tissues can be distorted by scar and the offending gland(s) can be in unusual locations.

The purpose of this study is to report the use of a quick intraoperative parathyroid hormone assay (QPTH) as a surgical adjunct in identifying and confirming excision of hypersecreting glands in patients with persistent or recurrent primary hyperparathyroidism undergoing an initial reoperative parathyroidectomy.

METHODS

Fifty consecutive patients with persistent or recurrent primary hyperparathyroidism underwent initial reoperative exploration in an attempt to control their symptomatic hypercalcemia. Of the 50 patients, 34 had persistent hypercalcemia after a failed initial parathyroidectomy, and a late recurrence of disease occurred in 14. Two patients could not be categorized because the time of recognized hypercalcemia after initial parathyroidectomy was not known. In recent years, the percentage of patients with persistent hypercalcemia after a failed first surgical procedure has increased.

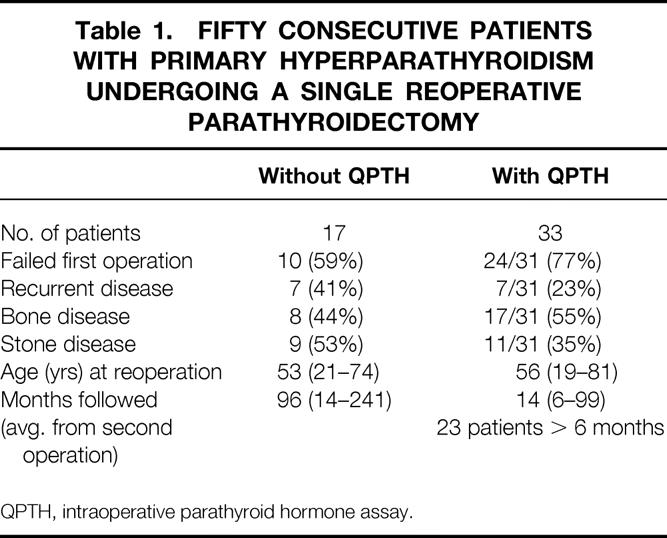

As shown in Table 1, these patients were divided into two groups. Seventeen patients underwent surgery between 1974 and 1990, before QPTH was available. In the more recent group, 33 patients underwent intraoperative hormone monitoring as a surgical adjunct during the reoperative parathyroidectomy. Both groups were similar in age and symptoms.

Table 1. Fifty Consecutive Patients with Primary Hyperparathyroidism Undergoing a Single Reoperative Parathyroidectomy

The methods used to measure the intact parathyroid hormone and the results of using this intraoperative adjunct in patients undergoing first-time parathyroidectomy have been published. 1–4 Briefly, plasma from a peripheral vein or a vein in the surgical field is obtained before or just after the cervical incision is made and later at specified intervals during parathyroidectomy. The intact parathormone molecule has a half-life of 3.5 to 4 minutes. If the hormone level falls >50% from the previous preoperative or preexcision level and is less than the starting value, the assay predicts postoperative normocalcemia.

The QPTH assay is a nonradioisotopic, immunochemiluminescent methodology (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, CA) performed in the operating room. This allows close communication between the surgeon and the technician, which is important when multiple samples are needed to localize an obscure gland. The assay has a 10-minute turnaround time.

All patients had attempts at preoperative localization. These studies varied over time with improving sensitivity; since 1993, our choice has been Tc-99m-sestamibi (DuPont Merck Pharmaceutical, Billerica, MA) tomographic reprojection (SPECT) nuclear scanning. 5

In addition to preoperative localization studies, several manipulations using QPTH have been developed for locating hard-to-find parathyroid glands in these previously explored necks. Differentiated venous sampling of the left and right jugular veins, using a small-gauge needle to obtain 6 cc of blood from each vein, can indicate which side of the neck to explore by showing an increase in the hormone level. This can be done before or soon after the incision is made. Another technique that has proved useful is that of stimulation by manual massage of a specific area, such as the upper pole of a lobe of thyroid gland or along the esophagus in the posterior mediastinum. Pressure on a concealed parathyroid gland in this way increases the gland’s output of hormone, resulting in a measured increase in the peripheral blood. This directs further dissection in the stimulated area.

The most useful function of this intraoperative surgical adjunct is its ability to confirm quantitatively when all hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue has been removed. When the surgeon is unsure of the excised tissue, a significant decrease in the hormone level indicates removal of a hyperfunctioning parathyroid gland. If the QPTH level remains high, more hypersecreting tissue must be found. This is often accomplished in less time than it takes for histologic confirmation of the questionable tissue by frozen section.

Before 1990, the normal calcium range was 9 to 11 mg/dl. Since then, it has been progressively lowered; now the normal range of total serum calcium is 8.4 to 10.2 mg/dl in our hospitals. A successful reoperation in the early group of patients without the benefit of QPTH was defined by having all serum calcium levels <11.0 mg/dl for 6 months or longer after parathyroidectomy. The 17 patients in this group have been followed for an average of 96 (range 14 to 241) months since their initial reoperative parathyroidectomies.

In the more recent group, where a return to a calcium level of 10.2 mg/dl or less is considered to be a successful outcome, five patients had a significant drop in calcium level (7.6 to 9.9 mg/dl) but were followed in the immediate postoperative period only. Five patients with normal calcium levels have been followed from 2 to 5 months after surgery. Twenty-three patients in this group have been followed for ≥6 months, with an average of 14 (range 6 to 99) months.

The results are reported from a single surgical procedure performed for persistent or recurrent hypercalcemia after initial parathyroidectomy and are not from multiple reoperative attempts to control the hyperparathyroidism.

RESULTS

Twenty-six patients scheduled for reoperative parathyroidectomy had Tc-99m-sestamibi scans for localization. If planar views from outside hospitals were inconclusive as to the location of the overactive parathyroid gland, sestamibi scans with SPECT were obtained. In this group of reoperative hyperparathyroid patients, the prediction of anatomic location of the hyperfunctioning parathyroid gland(s) by sestamibi scanning had a sensitivity of 78%, a specificity of 86%, and an overall accuracy rate of 83%. In these patients with previous cervical explorations, sestamibi scans had a false-positive/false-negative rate of 19%.

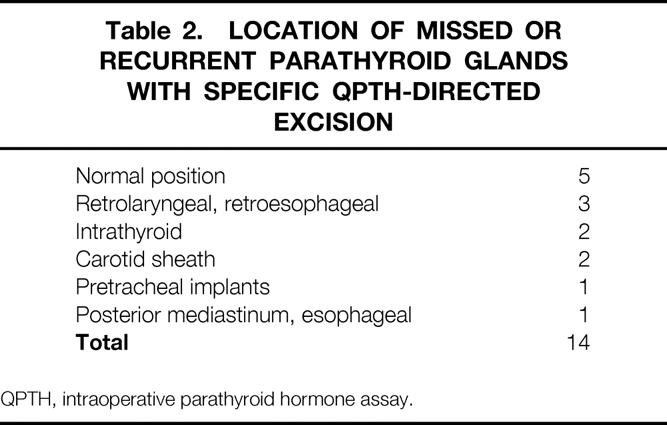

In the group of 33 patients who underwent QPTH monitoring during their initial, and only, reoperative parathyroidectomy, 31 returned to normal serum calcium or hypocalcemic levels. The intraoperative assay confirmed complete excision of all hyperfunctioning glands in 17 straightforward patients. In addition, intraoperative hormone measurements were found to be very useful in 14 (42%) patients by helping the surgeon identify and excise obscurely located or overlooked hyperfunctioning glands. Table 2 shows the location of these parathyroid glands found at the reoperative parathyroidectomy. QPTH assays were helpful in identifying these difficult-to-find parathyroid glands by facilitating localization with differential venous sampling (nine patients), measuring increase in hormone secretion after stimulation by local massage (three patients), correctly identifying abnormal tissue after false-positive/false-negative sestamibi scans (four patients), and providing quantitative assurance that excised tissue was or was not hypersecreting parathyroid tissue (nine patients).

Table 2. Location of Missed or Recurrent Parathyroid Glands with Specific QPTH-Directed Excision

In the group with QPTH, there were two (6%) surgical failures.

The first was a 52-year-old woman with symptomatic bone disease, a serum calcium level of 11.5 mg/dl, and a PTH of 141 (10–65) pg/dl. She had one parathyroid gland removed at age 21. At reexploration, three enlarged glands were excised, with no decrease in her circulating hormone level. Although her bone pain improved, hypercalcemia was present 1 month after her second operation. A persistent calcium level of 10.7 mg/dl with a PTH measurement of 127 (10–65) pg/ml 22 months later suggests the presence of a fifth parathyroid gland. QPTH predicted the surgical failure.

The second was a 49-year-old woman with multiple kidney stones. Her original parathyroidectomy was performed in 1976; at that time, two glands were removed. Before her reoperation, she had a serum calcium level of 10.7 mg/dl and a PTH level of 106 (10–65) pg/ml. One enlarged parathyroid gland was removed, and the QPTH suggested that all hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue had been excised. She remained hypercalcemic at 3 months, with a calcium measurement of 10.6 mg/dl and a PTH level of 82 pg/ml. There was a technical error with the intraoperative assay, giving the surgeon a false-positive reading. This was proven later by testing the control serum samples with a standard assay.

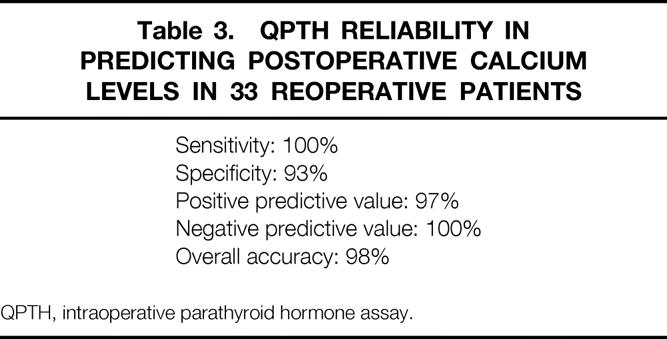

The reliability of the QPTH assay in predicting postoperative calcium levels in these reoperative patients is shown in Table 3. Except for the one technical error leading to a false-positive result, the predictability of the intraoperative test has an overall accuracy rate of 98%.

Table 3. QPTH Reliability in Predicting Postoperative Calcium Levels in 33 Reoperative Patients

Although the follow-up period is short, all patients in the QPTH group have normal calcium levels (≤10.2 mg/dl), with the exception of the two surgical failures mentioned above and three patients requiring calcium supplements. One of these patients had familial hyperparathyroidism and three normal-size gland “biopsies” in 1989. At age 29, with symptomatic bone disease, an intrathyroid hyperfunctioning gland was excised with a significant QPTH drop. She remains hypocalcemic, requiring supplementation 2 years after her second parathyroidectomy. Another patient underwent surgery in 1982, at which time two enlarged glands were excised. Over the years, he developed stones and mild renal failure. At his reoperative parathyroidectomy, a single hypersecreting gland was excised with a significant drop in QPTH. He has remained hypocalcemic for the past year. The third hypocalcemic patient had three normal parathyroid glands removed without resolution of her hypercalcemia or symptomatic stone disease. She was referred to our institution for reoperation, and a missed parathyroid adenoma was excised from her anterior mediastinum. She has remained hypoparathyroid despite two attempts at transplantation of fresh and cryopreserved pieces of her tumor. A preoperative attempt at QPTH localization showed no differential level of hormone because the venous drainage of the intrathymic adenoma was inferior to the needle placement in the internal jugular vein. The intraoperative hormone assay helped resolve hypercalcemia in 94% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism undergoing a single, reoperative parathyroidectomy.

Four patients remained hypercalcemic after extensive neck dissection in the group without QPTH. The reoperative failure rate in these patients was 24%. Seven of these 17 patients had late recurrence of hypercalcemia after a successful first parathyroidectomy, and calcium levels were still abnormal after surgery in only one patient. This patient, with familial hyperparathyroidism, had two glands removed and underwent a biopsy of one normal-sized gland at age 17 in 1976. At the time of his reoperation in 1988, the previously biopsied gland was removed and no other parathyroid tissue was recognized. His serum calcium level was 12 mg/dl 3 months later. He was later diagnosed with multiple endocrine neoplasia with an adrenal carcinoma and pancreatic insulinoma. In 10 patients with persistent hypercalcemia after their failed original operations, 2 had multiglandular disease and 5 patients had mediastinal tumors. Three of these patients with failed reoperations had subsequent thoracotomies to remove the offending glands. Had preoperative localization revealed these mediastinal tumors, thoracotomy with excision of the adenomas confirmed by QPTH would have precluded cervical exploration. In the entire series of patients who underwent reoperative parathyroidectomy, there was one postoperative death from comorbid disease and one laryngeal nerve palsy from excision of a missed retrolaryngeal tumor.

DISCUSSION

Reoperative parathyroid surgery has met with varying success rates, usually depending on the size of the reported series and the definition used to gauge the outcome. Recent studies have reported success rates of 65% to 98% 6–8 after the initial reoperative parathyroidectomy. However, because normal serum calcium ranges have changed in the last few years, it is important when evaluating these results to establish biochemical definitions. In addition, the length of follow-up and the number of reoperations per patient should be considered when reporting success rates. Outcomes reported in this study followed strict biochemical guidelines and are from a single, initial reoperation.

Although it is difficult to follow many of these patients after surgery because most have marked improvement of symptoms and a visit to the doctor for blood work is expensive, we have attempted to look at the 6-month surgical success rates and longitudinal outcomes. In the group of patients studied with QPTH monitoring, 10 have been followed from the immediate postoperative period to 5 months and have not yet been proven to be normocalcemic for 6 months. All of these patients had a marked drop in postoperative calcium levels and will probably remain at normal or hypocalcemic levels for the necessary study period. If we assume that these 10 short-term patients had successful revision surgery, the initial reoperative parathyroidectomy success rate based on a return to a normal serum calcium level of ≤10.2 mg/dl is 94%. Twenty-three patients in the QPTH group have been followed for an average of 14 (range 6 to 99) months, and all have had serum calcium levels of ≤10.2 mg/dl during this short follow-up period.

Three patients became hypoparathyroid, requiring exogenous calcium and vitamin D supplements to maintain normocalcemia, after the reoperative excision of a single gland in each case. Assuming that all initial surgical procedures were thorough and the extensive dissection, with or without biopsies, may have left some glands with a tenuous blood supply, more patients would be at risk of hypoparathyroidism if subjected to extensive bilateral reexploration. Thus, a limited dissection to remove the hypersecreting gland at reoperative parathyroidectomy would be desirable. This can occasionally be accomplished with a good preoperative localization study, dissection limited to the area of the overactive parathyroid gland, and excision followed by assurance that all hyperfunctioning glands have been removed, as proven by the intraoperative assay. Without extensive further exploration through scar tissue, the possibly tenuous blood supply to any remaining normally functioning parathyroid gland is in less jeopardy, thus decreasing the risk of hypoparathyroidism. This was possible in a small number of our patients. Seven patients had obvious missed glands that stood out on the localization scans and were easily removed with limited neck dissection in less than 1 hour of operative time. A significant drop in QPTH assured the surgeon that all hypersecreting parathyroid tissue had been removed, predicting a return to normocalcemia. Six of the patients went home the afternoon of surgery without an overnight stay in the hospital.

The other extreme of reoperative parathyroidectomy consists of patients with persistent or recurrent hyperparathyroidism who have difficult-to-find glands. In this series, QPTH played a significant role in the search pattern for these parathyroid glands. In trying to locate the hypersecreting parathyroid gland, 42% of our patients were helped directly by the use of QPTH. Differential venous sampling determined the lateral location of the offending parathyroid gland in 9/10 patients. In four patients with false-positive/false-negative sestamibi scans, the QPTH differential venous sampling technique localized the hypersecreting gland. This localizing technique, performed perioperatively, has replaced the invasive preoperative venous differential sampling by femoral catheter unless the suspected tumor is in the mediastinum. We also found that direct massage of a specific area containing an obscure gland caused a significant rise in the hormone level in plasma samples taken from a peripheral vein. This manipulation was helpful to the surgeon in three patients with glands in unusual locations.

The most helpful use of QPTH in these reoperative patients is its ability to give the surgeon quantitative assurance when all hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue has been removed. If the PTH level does not drop sufficiently after removal of suspected tissue, this indicates that further dissection is required to find all hypersecreting glands. However, if the excised tissue contains all of the hypersecreting parathyroid gland, the hormone level drops, predicting control of hypercalcemia and surgical success. This “biochemical frozen section” measures hyperfunction of the parathyroid glands and gives surgeons a timely and more accurate assessment of their surgical intervention than the histopathology of any excised tissue.

When reoperative parathyroidectomy is necessary, the surgeon needs as much help as possible to be assured of a successful return to normocalcemia. The intraoperative QPTH assay can be a direct contributor to improving the success rate in patients requiring a second operation for primary hyperparathyroidism.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Matthew Ruel for his data collection and excellent technical assistance.

Discussion

Dr. Arnold G. Diethelm (Birmingham, Alabama): The subject of parathyroid reoperation is important, as the operations may be technically difficult and intellectually challenging. The technique proposed by Dr. Irvin allows intraoperative confirmation of the parathyroid hormone and then confirms that this hormone level has returned to normal after you remove the offending gland.

The goal of the operating surgeon is to achieve a normal or near-normal postoperative calcium in an intact parathyroid hormone. But this may not always be possible and, on occasion, the operating surgeon needs to compromise. Certainly, the more information the surgeon has before the reoperation, the more likely the reoperation will be a success.

I’d like to ask several questions of Dr. Irvin. First, do you ever use selective preoperative venous sampling for parathyroid hormone to localize the abnormal levels of parathyroid prior to the operation and allow one to focus their attention initially on one side of the neck, thereby avoiding a bilateral neck exploration?

The second question is, what levels of calcium and intact PTH do you require for a patient who is asymptomatic to undergo a reoperation?

And, third, how does the intraoperative PTH sampling help the surgeon if the lesion is in the mediastinum? In other words, if you have a mediastinal parathyroid adenoma, how would you make that diagnosis intraoperatively in terms of sampling the jugular vein? In our experience, it has really been the superior caval sample that would tell you if the tumor is in the mediastinum, because most intrathymic parathyroid adenomas will drain into the superior cava.

Dr. Colin G. Thomas, Jr. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina): Since 1990, Dr. Irvin and colleagues have been refining and reporting on a methodology that, in their earlier papers, identified hyperfunctioning parathyroid glands with a sensitivity of 88%. When combined with an intraoperative test for PTH, complete excision of hyperfunctioning glands was accomplished in 98% of 85 unselected patients, as reported in 1996. Problems related to multiglandular disease, the incidence of 5% of secondary lesions, and the presence of false-negative or false-positive scans. They now bring this approach to the more complicated problems of reoperative parathyroid surgery.

You will recall that recurrence of disease is not unusual. The first patient, Albert Johnye, operated on by Felix Mandel in 1925, had recurrence of the disease. The tumor was never found. Furthermore, Capt. Martel required seven operations before the mediastinal tumor was found.

Dr. Irvin reports an improvement in his patients who were undergoing reoperative parathyroid surgery from 72% without intraoperative PTH to 94% with the availability of this test. I doubt, however, if there can be a valid comparison between 17 patients in the first group and 32 in group II, which would eliminate the confounding variables such as experience of the surgeon and improved imaging techniques. Regardless, the current results are very impressive, and congratulations are to be extended to him and his colleagues. I have several questions.

Could you be more explicit in describing your precise approach after finding an unsatisfactory or false-negative or false-positive scan? How many aspirates are usually required to localize the lesion and what are your criteria for massaging a particular area? Is this based on intuition, prior operative surgery, or other criteria?

Have you considered aspiration of a suspected mass and determination of the IPTH level in the aspirate? This should give you a clue as to the site of the tumor.

Are you concerned about the relatively short follow-up of 14 months? Whereas, in the first group of patients, 17 patients had late recurrence even though they had an immediate success rate after their initial parathyroidectomy.

Overall, Dr. Irvin and his colleagues should be saluted for their creativity and tenacity in developing an approach that would give a success rate of 94% in reoperative surgery and 98% in the virgin neck in the treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism. We should all pay attention and learn from this report.

Dr. Collin J. Weber (Atlanta, Georgia): Dr. Irvin and his colleagues are due congratulations for what I believe is a landmark observation in parathyroid physiology, namely, that the level of circulating intact PTH does in fact fall dramatically within 5 minutes of the resection of a parathyroid adenoma. Nobody knew that before George’s work.

I am rising to ask a question of Dr. Irvin, based on some data that we have obtained. Our hospital has not yet agreed to purchase these one-use item expensive kits nor to provide the on-call laboratory technician to operate them. And, therefore, in conjunction with Dr. James Ritchie of our division of laboratory medicine, over the past year and a half I have been collecting serum samples intraoperatively and having them assayed for free the next day by Jim Ritchie, and we have therefore been able to retrospectively analyze the impact these tests might have had.

We have found that in 49 of 50 parathyroid adenomas, the assay was extremely accurate. However, in more than 50% of double adenomas or primary or tertiary hyperplasias, George, it has been inaccurate. Primarily, it has been falsely positive. I hope you can all see. In the upper left-hand corner are the PTH values during the time course of the procedure. This happens to be a tertiary case, but it has also been true in primaries, Dr. Irvin. Here, the left lower is excised. And you will notice that the PTH falls to 66 very promptly. While I was looking at these three large glands, I did a subtotal resection leaving these remnants in place, and here was the final PTH.

I would appreciate it if you could comment on this, Dr. Irvin. At the present time, I am unwilling to leave enlarged glands in the neck and do continue, in primary cases, to explore both sides of the neck. But I also believe that your observation is extremely important regarding the pathophysiology, the functional characteristics of each of these parathyroid lesions.

I would also just like to echo Dr. Diethelm’s and Dr. Thomas’s comments, that in our experience preoperative localization has been extremely valuable in reoperative cases, particularly venous sampling.

Dr. Larry C. Carey (Tampa, Florida): Dr. Irvin, I just wanted to ask you, if you can rub the neck in the operating room and find the side the tumor is on, couldn’t you rub the neck before you got to the operating room and find which side the tumor is on? And wouldn’t that help you with your exploration?

Dr. George L. Irvin III (Closing Discussion): Dr. Diethelm, the selected PTH sampling is usually done after the patient is asleep. Luke Young, our anesthesiologist, has gotten pretty good with that little small needle, and he slips it right in either one of the jugular veins, and in 10 minutes, I will know which side to go on. This essentially has taken over from the older way of doing it in which we used to put a catheter preoperatively in these patients up the femoral vein and take differential samples. We don’t do that anymore, unless we think that it is in the mediastinum.

You can also do that after you have made your cervical incision. You can go right to the jugular vein on either side and take your sample right there at the operating table, if you cannot do it in an obese patient or somebody that they are having difficulty with through the skin.

The other thing is that it only works if the tumor, obviously, is upstream from where you put your needle. You notice that we have nine of these patients out of ten. The one that had the tumor found in the thymus and the anterior mediastinum, of course, was below where the needle was drawing the blood and, obviously, that is a negative finding.

The question of calcium and PTH levels in the asymptomatic patients—you know if the calcium is very high and is rising, obviously, you get concerned. And if the calcium is going to be up over 12 in these reoperative patients, yes, I think they should be operated on.

All of the patients here, except maybe two, I think, in the whole series, were actually symptomatic and had significant bone disease or recurrent stone disease. And so I think the indications for operation on these people were pretty clear-cut. So as far as the asymptomatic patient in reoperative parathyroidectomy, I think those people who have a moderate rise in their calcium can be watched.

We have mentioned the mediastinum. As far as the intraoperative PTH not being of much help, we also go with the sestamibi scan. If it is in the mediastinum, we have elected to go straight to where we think the tumor is, either thorascopically or through—in the case of one which was down in the aortic window—through a thoracotomy, and take out that tumor. If the PTH dropped, you know you got it, you don’t have to do the neck exploration.

Dr. Thomas asked about the short-term follow-up in these patients. And, yes, we don’t really know—and that’s one of the things we will have to watch very carefully—we don’t know whether the late recurrence rate in these patients which have a limited dissection will be higher than those that have bilateral neck dissections.

The massage and the scan are, I think, only used when we have trouble finding the tumor. In other words, if it is a very clear-cut patient where you know that the first surgeon just happened to miss it and you happen to go right in directly to it and you take it out—and these patients do quite well postop. We had seven patients in this series just like this. Direct excision—the operation took less than an hour in the reoperative case. Six of these patients went home without even an overnight admission to the hospital. So, occasionally, it is easy. The scan is very helpful in these patients, and I would agree with that.

On the other hand, you have this patient that I showed you the long graft on, where the operative procedure took about five-and-a-half hours. And this patient had been done by two of our ex-residents, and they were very, very careful. They had been from the angle of the mandible, including taking out everything in the neck just about, except the vital structures, and including the thymus. We couldn’t find it in all that scar, and that’s where the massage really helps you, if you get to an area where you think it might be and you massage, it does help by making the hormone go up. This patient did have a cyst involving a small parathyroid adenoma behind the esophagus way down in the posterior mediastinum, and it helped us to find the thing.

The size of the gland is not necessarily correlated with the amount of hormone that it puts out. To answer Dr. Weber’s last question, we don’t really know. You can’t correlate the size of the lesion found at surgery with the amount of isotope in the scan. What we are looking at here is simply an amount of hypersecreting tissue which we can take out and be sure that it is removed completely at the time of surgery. And that, in our hands, helps us assure success in these patients.

Footnotes

Correspondence: George L. Irvin III, MD, University of Miami School of Medicine, Dept. of Surgery (M-875), P.O. Box 016310, Miami, FL 33101.

Presented at the 110th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 6–9, 1998, The Breakers, West Palm Beach, Florida.

Accepted for publication December 1998.

References

- 1.Irvin GL, Prudhomme DL, Deriso GT, et al. A new approach to parathyroidectomy. Ann Surg 1994; 219: 574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irvin GL, Deriso GT. A new practical intraoperative parathyroid hormone assay. Am J Surg 1994; 168: 466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irvin GL, Sfakianakis G, Yeung L, et al. Ambulatory parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg 1996; 131: 1074–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carty SE, Worsey J, Virji MA, et al. Concise parathyroidectomy: the impact of preoperative SPECT 99m-Tc-sestamibi scanning and intraoperative quick parathormone assay. Surgery 1997; 122: 1107–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sfakianakis GN, Irvin GL, Foss J, et al. Efficient parathyroidectomy guided by SPECT-MIBI and hormonal measurements. J Nucl Med 1996; 37: 798–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low RA, Katz AD. Parathyroidectomy via bilateral cervical exploration: a retrospective review of 866 cases. Head Neck 1998; 20: 583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen W, Duren M, Morita E, et al. Reoperation for persistent or recurrent primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg 1996; 131: 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Järhult J, Nordentröm J, Perbeck L. Reoperation for suspected primary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]