To be elected to membership in the American Surgical Association is a mark of high honor and accomplishment for North American surgeons. But what has always impressed me is the active participation of leading surgeons from countries around the world, making it much more than an American Association. It is, in fact, the leading organization of surgeons, and to be elected President is the dream of every member. Thank you for making that dream come true for me.

Tradition dictates that the President provide his academic pedigree, perhaps to pacify some of the skeptics in the audience. But the importance of recognizing your mentors is not only to give them just credit, but also to remind us of the fundamental importance of mentorship and the opportunity we have to influence others. My personal list includes DeBakey, Morris, and Cooley from Baylor Medical School; Blalock, Bahnson, Spencer, and Kieffer from Hopkins; John Schilling and Rainey Williams, who gave me my first job in Oklahoma, and all my colleagues in the Surgery Departments at the Medical College of Virginia and the University of Michigan, whose accomplishments have allowed me to succeed as a Chairman for 25 years.

This year also marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Department of Surgery at the University of Michigan. Looking back, I can point with pride to the founder of the department, Moses Gunn. He was first in line to sign the roster of the first meeting of this organization in Philadelphia in 1882. That eagerness was quite characteristic of Moses, who came to Ann Arbor as a young surgeon, carrying a cadaver, so that he could teach anatomy and be the prime candidate for the school that was being formed. After the Civil War, he tried to move the medical school to Detroit and when the Regents refused, he moved to Rush Medical School in Chicago. However, when he was elected President of the American Surgical Association in 1885, he was still in Michigan. There have been two other Presidents from the University of Michigan: C. B. deNancrede in 1908 and Frederick A. Coller in 1943, whose endowed Professorship I am privileged to occupy.

Although this seems to be an era of public confession, the topic I have chosen has nothing to do with my marriage since the most important person in my life is my wife, Sharon. Her love, trust, and wise counsel have been a constant source of support and inspiration. Our marriage grows stronger with each passing year, as should any successful partnership. But not all partnerships behave in this way, and there is a particularly troubled one that I have chosen as my theme for this address. It is the traditional partnership between physicians and nurses that has concerned me for some time. The problems I see include failure to communicate effectively and fundamental differences in the perception of what the role of nursing ought to be.

The history of nursing is synonymous with the story of Florence Nightingale and her efforts to improve the care of the wounded in the Crimean War. She established the principles under which women could provide comfort and care in what had been the male-dominated hospital environment. These principles included, first and foremost, that the nurse should carry out the medical officer’s orders. She also insisted that charges or reprimands be made to the nursing superintendent who was responsible for maintaining discipline. This hierarchy of matron or superintendent over sisters or head nurses, who in turn were responsible for ward maids or scrubbers, became the precedent for all European hospitals. To provide consistent quality of nursing, a period of training was required, and Nightingale schools of nursing were established in London and other cities in Europe.

In the United States, the first suggestion for a national nurse training program actually came from our founder, Samuel D. Gross, as a result of his travels to Germany and Britain. He presented his views of a physician- controlled system of schools sponsored by county medical societies to the AMA, and his plan was adopted in 1869. However, no schools were established, and there was not much public support for hospitals or nurses until 1871, when the corruption of Boss Tweed in New York was exposed. Tweed had managed to gain control of the Board of Supervisors in order to control patronage. He and his cronies sold city jobs and tax rebates, controlled all city contracts, and issued bonds at extravagant rates of interest. Thomas Nast’s famous cartoons were instrumental in making the public aware of the scandal despite threats to Nast’s life.

Against the resulting backdrop of public outrage, a remarkable woman named Louisa Schuyler became interested in the deplorable state of patient care at Bellevue Hospital. A great-granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton, she had already played a significant role in founding the Women’s Central Association for Relief during the Civil War, which became the parent of the American Red Cross. She assembled a committee of strong-minded women who visited the hospital and found that the meager nursing care provided came from women who were vagrants or ex-convicts, each assigned to 25 patients; instead of night nurses, there were three night-watchmen who made rounds on 800 patients. The concerned women found an ally there in an intern named Gil Wylie, who later went to London, at his own expense, to learn more about Miss Nightingale’s school. As a result of their efforts, the New York Training School for Nurses was established in 1873 under the direction of Sister Helen Bowden from University College Hospital of London. One graduate of the original class was made Superintendent of the Boston Training School. Other graduates went on to found schools in Baltimore at Hopkins, in Chicago at Cook County and St. Luke’s, in Indianapolis and Washington, and abroad in Turkey, Japan, and China. In 1887, a school for training male nurses was also established at Bellevue. These original schools were connected to public, nonsectarian hospitals, but there was also a great deal of interest in similar programs by Roman Catholic and Anglican sisters and Lutheran deaconesses, who established their own schools in Springfield, Illinois, Brooklyn, and Chicago. Their success was assured by their energetic correction of the filth and disorder, the atmosphere of immorality and irresponsibility, and the tradition of neglect and corruption. This brought nursing to a new level of public respect and began its evolution from a vocation to a profession.

In the South, it was the Civil War that set the stage for the entry of women into military hospitals. My own interest in the Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, was stimulated by its remarkable size of nearly 5000 beds and its experience in treating 76,000 patients during the war. In reviewing the records, I came across the story of a remarkable woman, Phoebe Yates Pember, who was the first woman appointed as administrative matron there in 1862. She was the fourth of six daughters born to a prosperous Jewish family of Charleston, South Carolina. Her husband had died of tuberculosis at the age of 36, and as an energetic supporter of the Confederacy, she welcomed the opportunity to contribute to the care of the wounded. Her reception was less than cordial, with one of the ward surgeons complaining to a friend in disgust that “one of them had come.” 1 But with the support of the surgeon-in-chief, James McCaw (who later became Dean of the Medical College of Virginia), she was able to improve the food and care of the patients, ignoring the opposition and prejudice. Her biggest battle was for control over the most popular medication, whiskey. This commodity was costly and at $4 million, was 20% of the Army Medical Department’s appropriation in 1865. It was also a symbol of authority in the hospital and there was constant friction over its control between male and female contingents. To make matters worse, a few of the patients were contemptible malingerers. One day at the end of the war, one of them tried to force her to give him more whiskey. He called her an indecent name and grabbed her shoulder, but then beat a hasty retreat when he heard the click of a pistol she had concealed in her pocket. She was not very happy about having to ration the supply of alcohol, and as she wrote, “there were some doubts afloat as to whether the benefit conferred upon the patients by the use of stimulants counterbalanced the evil effects they produced on the surgeons”; as she described it, “when the patient was being made ready for an amputation, it was customary for the surgeon to match the patient drink for drink.” There were more unfortunate examples, such as setting the wrong leg in splints, but for the most part, the surgeons did remarkably well considering the limitations under which they worked.

Mrs. Pember was often more than a witness to the surgical limitations of the times. She described her affection for a young man who had convalesced from a hip wound for 10 months, gradually leading to successful walking from one end of the ward to the other. Unfortunately, one night as he turned over in bed, his wound began to bleed profusely, whereupon she stopped the blood flow with her finger and sent for the surgeon. The doctor concluded that the severed artery was too deeply imbedded in the thigh to be repaired. When informed of the hopelessness of his plight, the young man gave the matron his mother’s address and asked, “How long can I live?”

“Only as long as I keep my finger upon this artery,” Mrs. Pember replied.

The silence was broken by a simple remark, “You can let go.”

“But I could not,” wrote Mrs. Pember in her memoir, “not if my own life had trembled in the balance. Hot tears rushed to my eyes, a surging sound to my ears and a deathly coldness to my lips. The pang of obeying him was spared me,” she added. “For the first and last time during the trials that surrounded me for 4 years, I fainted away.”

Today, the Chimborazo Hospital and that unfortunate era are only memories, and the site is a park in which there is a commemorative sign post.

Charles B. deNancrede, who was chair of the Department of Surgery at Michigan and an early President of the ASA, presented a paper at the 1899 meeting entitled “The Effects of Modern Small-Arm Projectiles, as shown by the Wounded of the Fifth Army Corps, during the Campaign Resulting in the Capture of Santiago de Cuba” which reflected his experience in the Spanish-American War. 2 In the discussion, P. S. Conner stated,

“As regards nurses, there needs to be an altogether radical change. The nursing force during our late war was extremely defective in very many respects—in character, in efficiency. The great majority of nurses were male and were of very little value … I am inclined to take exception to one remark made with reference to nurses, and that is that women can never be taken toward the front during a battle … . In Cuba, more than one woman did effective work well at the front, and there is no reason why in many instances with a moving force, women nurses should not be carried along with the force … . It is one of the glories of the American soldier that though there were fifteen or sixteen hundred nurses who attended the sick and wounded in military hospitals, in not a single instance did they complain of any discourtesy shown to them by the men for whom they were caring.”

But there was always some tension, particularly between nursing and physician leaders. At the 1938 meeting of the ASA in Atlantic City, President Arthur Elting of Albany, New York, spoke on “The Relation of the Surgeon and Hospital.” 2 He focused on the problem of nursing education, saying,

“Very important changes are being made in the basic education of the nurse, many of which are excellent and many are not. The great danger to nursing as a profession today … is that its direction and control are largely in the hands of women of great crusading zeal whose minds are filled with fine theories but who often do not possess the practical knowledge and skill required for the training of efficient nurses.”

With great foresight, he also expressed concern about the “national regimentation of medicine … by administrative officials in Washington.” 2

Thirty years later, at the 1968 meeting in Boston, there was much interest in and enthusiasm for the emerging role of computers in patient care. But a very perceptive paper by James Maloney, Jr., pointed out that nurses had begun to watch computers instead of patients, and that actual contact with the patient was decreased. 2 In addition to his concerns about the inability of the computer to render clinical judgment, he was particularly critical of team nursing involving nonprofessionals. He said, “the development of team nursing has, unfortunately, changed the nurse from a professional colleague of the physician to a data-collector at the central nursing station, while nonprofessionals contact the patient.”

The discussion of the papers on computers included the wry comment of J. E. Dunphy that since they had not had the funds to buy expensive computer hardware, they had redesigned the wards to have managers and clerks at the desks and nurses at the bedside. 2 He spoke of a “remarkable revolution” where the chief nurse made rounds every morning with the chief resident. The result was that they were both fully informed as to what was going on and there was a tremendous increase in morale.

One of the societal changes during the 1960s was the political emphasis on quality healthcare as a right for all citizens. Because access to all levels of healthcare services was seen to be the limiting problem, the nurse practitioner, or NP, role was developed to meet the demand for primary care services. The first formal education program for NPs was established at the University of Colorado School of Nursing in 1965. It was designed to prepare nurses to deliver primary care to children in underserved communities. Within 10 years, such programs had proliferated and NPs were being trained in a variety of fields. The programs had moved from 1-year nondegree status to graduate programs leading to a masters degree in nursing. This increase in responsibility stretched the licensure definitions of nursing, requiring changes in state laws. Because medical licensing laws were written long before any other profession, it required both legal and political leverage to introduce a “diagnosing function” to the traditional definition of nursing. Idaho was the first state to do so by legislating an exception to the statute that prohibited unauthorized diagnosis and treatment, but it remained for New York State to actually redefine nursing:

“The practice and profession of nursing … is defined as diagnosing and treating human responses to actual or potential health problems through such services as case finding, health teaching, health counseling and provision of care supportive to and restorative of life and well being.” 3

Notice that the definition uses the term “human response” as the object of treatment rather than “disease,” which is central to medical practice acts. Also, the definition uses the verb “care” rather than “cure.” In a practical sense, it is the difference in what we mean when we say that we are going to “nurse” a cold by improving our comfort and environment, or “doctor” a cold when we use medications.

With the further development of advanced nursing practice, the distinction between NP and physician roles began to become less distinct, because NPs performed interventions to cure acute minor illnesses and injuries on a regular basis. And because optimal primary care involves both caring and curing, the additional provision of teaching for both patient and family by NPs became a very effective combination of professional skills. Of course, the argument can be made that there is potential risk involved if the patient’s apparently minor problem is a more serious disorder that might be detected by a physician. An interesting experiment in this regard was run by the Carondelet St. Mary’s Hospital in Tucson, Arizona. There, nurses were allowed to take on a managed care project and run it themselves. 4 Nurses were the primary care providers, arranging for whatever treatment was needed within or outside their network. This Community Nurse Organization (CNO) was very cost effective, and by 1994 had a demonstration project award from HCFA and was competing successfully with regional HMOs. 5 If you were a primary care physician, this would raise some concerns about job security, but managed care has made job security even more problematic for nurses. As Jane Schweitzer points out in her book Tears and Rage: The Nursing Crisis in America, 5 hospitals usually lay off nurses first as part of the “restructuring” to control rising costs. The shortstaffing that results leads to both patient and the remaining nurses’ dissatisfaction. As the nursing workload increases, error rates increase, especially if nurses were replaced with less well-trained staff. The underlying problem of wasted nursing effort on clerical work, changing linens, removing trash, and picking up meal trays is rarely addressed by hospital administrators. In fact, hospital administrators have become a major focus of nursing antagonism.

Concerns about nurse staffing under managed care ultimately found their way to Washington and led to a congressional mandate to the Institute of Medicine in 1994. The charge was to determine whether there was a need for more nurses in hospitals and nursing homes. The issues were the quality of patient care and work-related stress among nurses. A committee was formed under the leadership of Frank Sloan, an economist from Vanderbilt, and Carolyne Davis, a nurse-educator who subsequently headed HCFA. Their investigation involved literature reviews, public hearings, and site visits. They concluded in 1996 that the number of RNs was sufficient to meet national needs, 6 but they did recommend better staffing patterns and also specific research into the relationship between quality of care and nurse staffing levels. They suggested Congress set as a goal for the year 2000 a requirement that there be 24-hour coverage by RNs in nursing facilities. This was an increase over the existing 8-hour requirement. Most nursing stress, however, is a product of the work environment, and physicians usually get credit as the major source of conflict. Surveys show that as many as two thirds of nurses claim to be verbally abused by physicians at least once every 2 to 3 months, and 12% report having had something thrown at them in anger. It turned out that many of the abusive physicians were victims themselves of protracted verbal abuse during their training.

Much of the conflict is rooted in the historical dominant role of the physician and subservient role of the nurse as envisioned by Nightingale. This relationship has continued to be reinforced by gender, education, and remuneration. There is also the more fundamental issue of how men and women relate to each other. In a fascinating book, Talking from 9 to 5, Women and Men in the Workplace: Language, Sex and Power, Deborah Tannen highlights the behavioral differences that actually originate in childhood. From the time they are little, girls learn that sounding too sure of themselves will make them unpopular with their peers and with adults. They are also discouraged from taking leadership roles to avoid being labeled “bossy” and learn to exert influence on their group by making suggestions rather than giving orders. Boys, on the other hand, are in a different social structure that is clearly competitive and that rewards aggressiveness. Boys learn to state their opinions in the strongest terms and find out if they’re wrong by seeing if others challenge them. This conveys confidence and translates in the workplace into behavior that is an advantage in hiring and promoting. Women are more likely to speak in styles that are less effective in getting recognized and promoted. An aggressive man is usually labeled a “go-getter,” while an aggressive woman usually wins the label “bitch.” As a result, women must learn to modify their behavior to succeed in positions of responsibility. Tannen states that in talking to women physicians, she heard conflicting stories about the problems or positive relationships that they had with nurses. An explanation was provided by a prominent woman surgeon who said that she began her career by adopting a military approach and barking her orders to the nurses. That didn’t work, so she found a way to be firm without sounding authoritarian. Women physicians also speak differently to their patients than men, and women lawyers behave differently in court. In fact, women are often more successful in taking depositions by using a sympathetic approach and charming witnesses into forgetting that the attorney is their adversary. But women in positions of authority generally find it difficult to balance the expectations of being in control and retaining feminine behavior.

As nurses began to improve their education and experience, they wanted to contribute more to patient care, but usually had to be satisfied by making their recommendations in a way that made the physician believe they were his own. This role-playing is similar to the interactions between husband and wife portrayed in television situation comedies in the 1960s. Similarly, Hollywood has not been kind to nurses, tending to portray them as sex objects, or worse, as villains. The classic example is Nurse Ratched from the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Her cold and ruthless behavior was matched by an indifferent psychiatrist as a frightening example of the worst kind of institutional care.

But nursing education was progressing from the apprenticeship model in hospitals to the university setting where women found not only more intellectual stimulation, but the powerful voice of feminism. Further recognition as a scientific profession occurred with the establishment of the National Center for Nursing Research at the NIH in 1986, which in 1993 became the National Institute of Nursing Research with expanded functions and funding.

As medical and nursing science advanced, nurses were required to learn more and do more for the patient, but often with little improvement in their salaries. They encountered considerable resistance when they began to seek improvement in pay and often were not supported by physicians when they challenged hospital administrators. In Denver in the 1970s, they were successful only when they pointed out that they were paid less than tree-trimmers for work that required considerably more education and responsibility. Not all such efforts were successful, however, and in some areas, frustrated nurses found a willing ally in the labor unions. In my own state of Michigan, the nursing union was founded in 1975, and I had a rude introduction to it in 1989 when they went on strike. Such an action seems counter to nursing professionalism in my view, because it indicates a willingness to jeopardize patient care. My testimony in court to obtain an injunction against the strike did not improve my own nurse/physician relationship, but it did restore patient care. Interestingly, the most damaged relationships were between the nurses who had refused to strike and reported to work, and those who walked out. In contrast, the working relationship that we have with the residents, who also are unionized, has allowed us to support their legitimate requests for improved working conditions and pay.

It seems clear that the partnership envisioned by Nightingale is in trouble and that the consequences are potentially deleterious to the patient. Nurses’ frustration with their status has led to the development of more independent behavior and more distancing from the physician. To document their independence, extensive time and effort are expended on chart notations, and a direct nurse-client relationship is cultivated under the concept of primary nursing. With this distancing, suspicion and distrust can flourish and poor patient outcomes deteriorate further into blaming and medicolegal actions (Fig. 1). Some have even accused nurses of “bounty-hunting” by collaborating with plaintiff’s attorneys. Even if the behavior doesn’t reach this level of destructiveness, it certainly detracts from patient care. In the absence of a collegial and collaborative approach, other healthcare providers, such as physician assistants (PAs), and other working relationships such as clinical nurse specialists have been developed. Nurse specialists have been much more successful in physician collaboration because of their advanced knowledge and training. In fact, they characteristically serve as case managers and often take the lead in developing the clinical pathways that facilitate patient care and shorten hospital stays. But at the staff nurse level, problems in communication remain.

Figure 1. Poor nurse/physician communication leads to polarization of efforts to care for patients.

In January 1996, while rounding on one of my patients, a nurse appeared with a syringe to add to the patient’s intravenous fluids. When I inquired what it was, she stated that it was potassium and when I asked further whether she knew what had prompted the order, she shrugged her shoulders and walked out. The patient was no more pleased with this response than I was and pursued it further by asking why it was that the nurses were unable to tell her the reason for a diagnostic test that had been ordered. It was obvious that this was not the model of teamwork that either of us expected. When I went to the Director of Nursing with this issue, I was told that she would look into it. At my subsequent regular meeting with the Head Nurses, they reacted favorably to my suggestion to try to improve communication, and two of them offered to serve as locations for pilot projects. But 4 months went by, and when I pressed the issue, I was told that the decision had been made to consider it as a suitable project for nursing research. Another 6 months went by before a faculty member of the School of Nursing was identified, but at least she had an interest in the problem; in fact, her doctoral dissertation was entitled “Nurse Management of Conflicts with Physicians in Emergency Rooms.” 7 What Gail Keenan found in a study of 36 emergency rooms was that they functioned with traditional hierarchies. The physicians had all the sanctioned authority and the climate was one of aggressive behavior. Now the traditional concept is that this is much less conducive to conflict resolution than a constructive work environment that encourages humanistic behavior. However, nurses were quite able to manage conflicts proactively in the ERs using a variety of constructive negotiating styles. With this background of her experience in the ERs, Dr. Keenan proposed a three-phase study to address my concerns, beginning with a survey to determine issues common to both nurses and physicians. Baseline measures of the perceived quality of nurse/physician communication and attitudes were obtained from two study groups on the Neurosurgery and Vascular Surgery units, along with a patient satisfaction assessment of the nurse/physician collaboration.

In the second phase, four-member task groups were appointed, consisting of two RNs and two MDs who had indicated a willingness to serve. They were charged with selecting an issue and working with an impartial facilitator to resolve it. Expert facilitators were hired for this purpose and were supported by a grant that Dr. Keenan had obtained for the study. Each group met for four 2-hour sessions off-site and all meetings were videotaped for analysis. A comfortable atmosphere with food was provided, and phone-pages were intercepted so as not to disrupt the sessions. The first group in Vascular Surgery worked on a plan to enhance the quality of physician rounds by written communication, and the second in Neurosurgery created a plan for joint walking rounds.

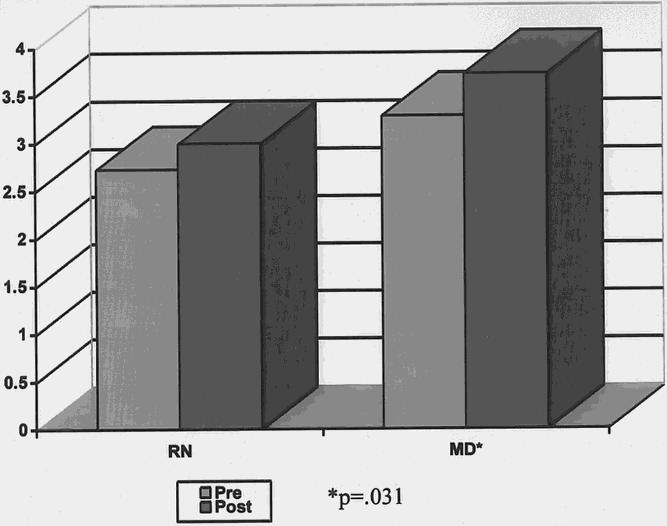

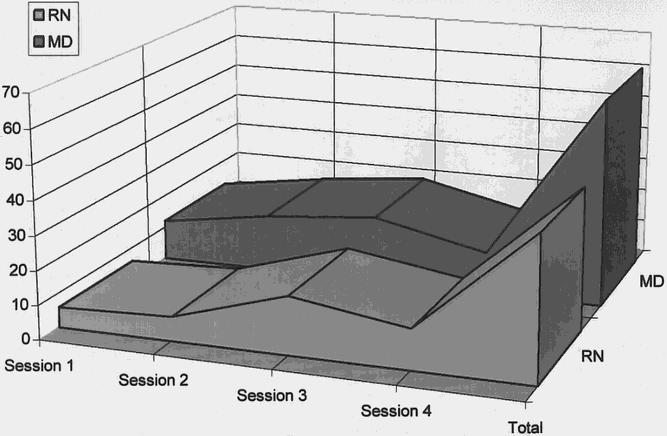

The third phase proceeded with implementation of the plans, and 6 months later, a follow-up survey was conducted to evaluate the intervention. When the data were analyzed, there were no differences between the two specialty work groups, but there were statistically significant differences between nurse and physician perceptions. Physicians considered physician-to-physician communication to be more open and accurate than nurses perceived their own nurse-to-nurse communications. Physicians also believed that communication and conflict management between nurses and physicians was more open and collaborative than nurses perceived it to be (Fig. 2). The videotapes were particularly informative when analyzed for amount and types of verbalizations during the sessions. Again, there were no differences between the two specialty workgroups, but there were major differences between nurses and physicians. As a percentage of the total, nurses used significantly more “support/agreement” messages than physicians, who used more “give opinion” messages than the nurses. Physicians also produced more verbalization “talk-time” than nurses in the first two sessions, with subsequent sessions becoming more evenly distributed (Fig. 3). The proposals were implemented to everyone’s satisfaction and the project was considered a success at the time of final evaluation in October 1998. Both solutions remain in place to date, although the suggestion by Dr. Keenan that the process be extended to other units in the hospital has not occurred. It seems clear that in their reluctance to be seen as subservient to physicians, some nursing administrators resist any change in working relationships that promotes cooperation. Front-line nurses, however, seem much more likely to recognize the need and proved much more willing to support the concept of collaboration.

Figure 2. Comparative nurse (left) and physician (right) responses to questions about conflict management before and after the collaborative project.

Figure 3. Differing levels of talk-time between nurses and physicians in each of sequential sessions. A more balanced relationship was seen in the later sessions.

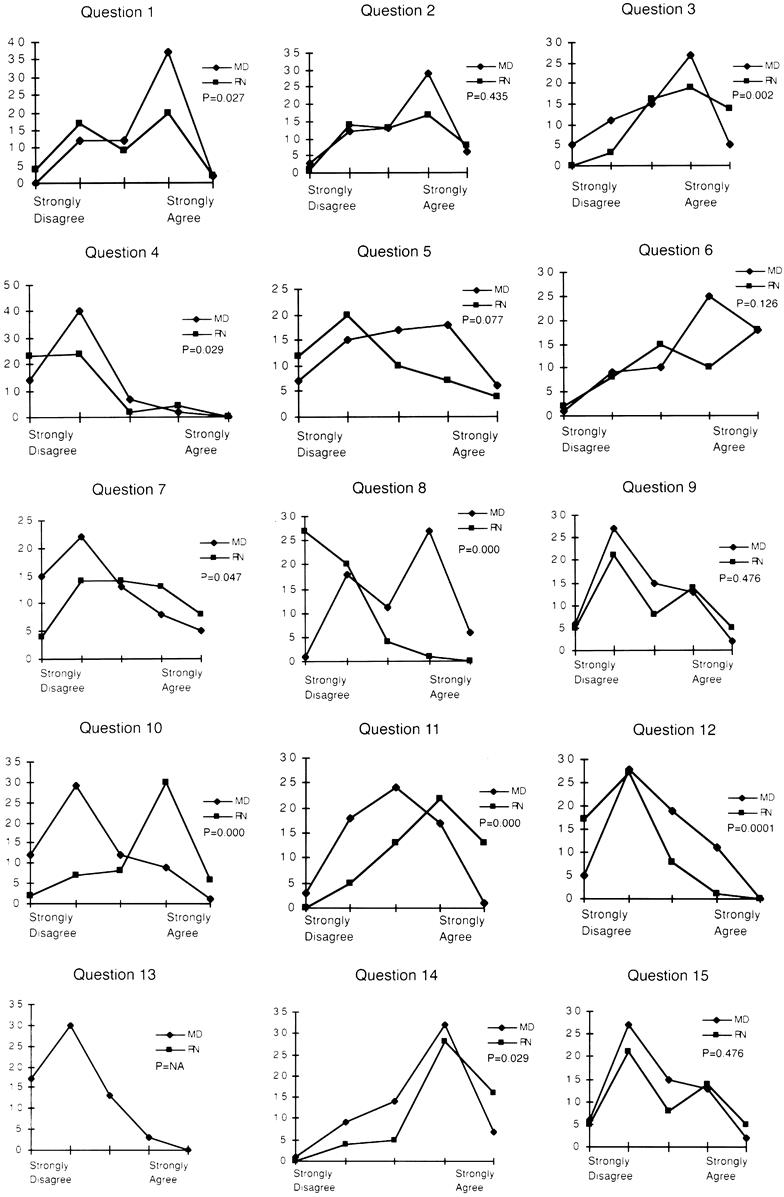

A more recent example of this occurred this year when I decided to sample nurse and physician responses to a series of provocative questions developed with the help of my research associate, Mary Proctor. I wanted to find out just how much difference there was in attitudes and from this learn more about the barriers to communication. I passed out the survey to the faculty of our department and selected a group of vascular surgeons from ten medical centers who I knew were clinically active. I also approached the nursing leadership for their support in circulating the survey to our own staff nurses. The reaction I received can best be characterized as an overreaction. They were upset that I had not consulted them before developing the questionnaire, even though I had involved two nurses in the process. They were concerned that I was raising issues that did not have an easy resolution and that I had no plan to correct the problems. They were particularly concerned about the question related to the nursing unions, which they felt would produce backlash. The first barrier proposed was the lack of IRB approval of the survey, and when I resolved that with a waiver, they insisted that I remove the question regarding unions, which I agreed to do. After all that, these are the results with 53 nurses and 63 surgeons responding (Fig. 4):

Figure 4. Comparison of nurse and physician responses to the survey questionnaire.

• Question 1: Patient care communication between nurses and physicians is open and effective. As shown in the responses, physicians had a much more positive view of the interaction than nurses (p = 0.027).

• Question 2: In the documentation of patient care, there is frequent duplication of effort between nurses and physicians. Nurses and physicians generally agree that there is duplication of effort (p = 0.435). There is probably disagreement, however, on which activities should be discontinued and by whom.

• Question 3: Formal disciplinary action is more likely to be sought by physicians against nurses than against other physicians. There is agreement on this issue, but it is significantly more strongly felt by the nurses (p = 0.002). It represents a predictable outcome to poor communication.

• Question 4: Nurses role in patient care should not go beyond following physicians’ orders. Here, too, there was agreement that nurses should do more, but interestingly, physicians were more strongly supportive of nursing responsibilities going beyond their orders (p = 0.29).

• Question 5: Physicians use nursing evaluation and documentation to plan patient care. There was considerable variation in the responses to this question with what appears to be a more negative view by nurses although not statistically significant (p = 0.077).

• Question 6: The time nurses spend in chart documentation would be better invested in patient care. There was general agreement on this issue which also brought out written comments by nurses expressing their frustration with the required documentation which frequently kept them overtime (p = 0.126).

• Question 7: Communication between male nurses and male physicians is more collegial than between female nurses and female physicians. This question on the gender issue was actually supported more by nurses than by physicians (p = 0.047).

• Question 8: The best nurses practice in specialized areas like the intensive care units. This question struck a nerve among the staff nurses and showed a polarization in attitudes (p = 0.0001). It is probably comparable to a survey of physicians on the premise that the best doctors work in the operating room.

• Question 9: There is no difference in nursing performance attributable to the preparation they received, i.e., hospital-based, associate degree, or baccalaureate. This was the other question of major concern to the nursing administrators, who consider it to be a volatile national problem for nursing. It turned out to produce a mixed response, but we have no way of knowing the educational background of the nurse responders (p = 0.476).

• Question 10: The major responsibility of the nurse is to serve as the patient’s advocate. This was another polarizing question with nurses strongly supportive and the physicians opposed (p = 0.0001). Physicians might be less offended if the object of the advocacy had been more specific, such as to overcome bureaucratic obstacles to care.

• Question 11: Nurses do a better job than physicians in the management of the dying patient. Here again, the nurses see their role and effectiveness in more positive terms than physicians (p = 0.0001). Physician interventions to prolong life are often seen by nurses as futile and discomforting to the dying patient—another area where open discussion would prove beneficial.

• Question 12: Physicians understand the science and scope of the practice of nursing. There was a high level of agreement here on physician’s lack of familiarity with nursing practice (p = 0.0001). We should certainly be more familiar with the changes that have taken place in nursing education and training.

• Question 13: Nursing’s perceived lack of power and respect justify the formation of labor unions. This was the question that had to be deleted from the nursing survey, so only the physician responses are shown, which reflect very little support for unionization.

• Question 14: The education and training of nurses and physicians should be coordinated to allow more professional interaction. There appeared to be general support for this, but it was significantly stronger from nurses (p = 0.029). Until this occurs, we are not likely to be able to achieve coordinated care.

• Question 15: The quality of nursing care has improved significantly during the past 20 years. This question was also subject to variable interpretation. The nurses who disagreed wrote that they felt that their limitations were based on excessive workload. Physicians were less impressed with an improvement in quality (p = 0.026). The nurse administrators also wanted to know why I had not included a question on whether there had been any improvements in physician care in the past 20 years.

In contrast to the pessimism of the nursing administrators, the nurses who provided the responses were supportive of the survey; one wrote: “I have been waiting for this survey all of my life. Thank you!” But it is obvious that there are fundamental differences in viewpoint, especially concerning the nurse’s role as patient advocate and in the care of the dying patient. There is agreement on the potential value of a shared educational experience.

The prospect of collaboration, however, raises serious issues with physicians, many of whom see it as further erosion of their position of authority and power. In particular, the potential for competition and disputes has been viewed with concern by both nurses and physicians, with nurses feeling threatened by responsibility and accountability. Judith Baggs reviewed the status of collaboration between nurses and physicians and found it difficult because of fundamentally different viewpoints of the expected balance of power between nurses and physicians. 8 Physicians expect nurses to act as physician extenders, while nurses expect to use their knowledge to direct patient care.

One of the earliest efforts to promote collaboration was the formation of the National Joint Practice Commission in 1971 by the AMA and the American Nurses Association. They proposed five guidelines, including establishment of a joint practice committee, primary nursing, encouragement of nurses’ individual clinical decision-making, integrated patient records, and joint patient care record reviews. 9 Several model units were established with subjective evidence of increased quality of care, patient satisfaction, and nursing job satisfaction. But this approach evolved to physicians accepting nurses’ input and then making the final decision. Interestingly, most nurses were satisfied with this and did not want more responsibility. An interesting perspective on this was provided by Adele Pike, who described the appealing role of the nurse as victim, with the ability to avoid responsibility and accountability by assigning blame to external forces. 10 This reflection of diminished professional stature has been addressed by calls for nursing leaders to push ahead with their own agendas without waiting for physicians to change. By defining themselves as colleagues, nurses hope to improve their relationships with physicians, but even more to establish their worth to healthcare administrators and to third-party payers. Recently, the Provost at the University of Michigan approved the establishment of a clinical practice plan for the School of Nursing. The lack of any discussion between the Schools of Medicine and Nursing regarding this step convinces me that we had better be a part of this change, rather than continuing to be perceived as part of the problem. It is also important to remember that there are more than 2 million nurses in the country, outnumbering physicians 4 to 1. Without better communication and planning, the relationship is like parents dealing with aggressive adolescents who crave independence but are having difficulty defining it. And so far, no one seems to be paying much attention to the most important individual, the patient, who has much to lose or gain in the resolution of this conflict. In my view, we are carrying far too much baggage of the old hierarchy to expect to resolve the differences easily. There was good reason for Moses to wander in the desert for 40 years until a new generation that had not been raised as slaves could appreciate the possibilities of the Promised Land.

What can we do to improve the situation?

1. We should promote the development of a curriculum of clinical care for both medical and nursing students that can bring to the patient the very best that both disciplines have to offer. The combination of nursing’s approach to the patient’s environment, family needs, and disease education is complementary to the disease-focused approach of the physician.

2. We should promote joint clinical training of nursing and medical students. Until we can bring this approach to fruition, we must establish better communication and help to establish a collegial role for nursing.

3. We should develop guidelines for charting that promote complementary patient assessment and allow nurses to participate in decisions. There are certainly areas where nurses can be granted some independence in decision-making, such as advancing diets and administering analgesics for mild aches and pains. This latitude would not only expedite patient care but would reduce the time spent looking or waiting for physicians. Frankly, it is economically foolish to spend so much on nursing education and compensation and not take full advantage of their training and experience.

4. We should require daily communication between nurses and physicians on all inpatients to improve coordination of patient education and care.

5. Finally, we should develop incentives to reward collegial behavior and discourage the dictatorial behavior that sets the wrong example for trainees.

Nursing’s own view of the future goes well beyond additional responsibilities for patient care. As pointed out by Sullivan in her book Creating Nursing’s Future, nurses might hope for a radical change in the structure of healthcare in which they act as the primary managers of care and physicians report to them.12 Because this is unlikely, nursing leaders anticipate that their holistic approach to patient and family care will finally be recognized as integral to the system. They would like to serve as the first line of care promoting healthy communities and as partners in the health team. The forces tending to favor this view include the increased trust in nurses and loss of confidence in physicians as patient advocates, the growing movement to patient self-determination away from the authoritarian, physician-dominated role in care, and the broader definition of healthcare to include prevention of disease and promotion of healthful behavior. Also, the changing demography with more older people needing chronic care, the recognition of women’s health as a neglected area, and the fears of rationing of services through managed care support a stronger role for nursing.

In 1990, business and community leaders from a rural area of Tennessee approached the Colleges of Nursing and Medicine at East Tennessee State University for assistance. They needed to rebuild after closure of the small local hospital and loss of 9 of the 12 physicians in the county. With unemployment at 35%, they needed to establish a healthcare system to attract new business and build tourism. To satisfy the need, two clinics were opened in Mountain City, Tennessee: one was run by the Family Medicine Department and the other was a primary care practice operated by NP faculty from the College of Nursing. Rather than compete, a family medicine physician agreed to serve as preceptor for the NPs to facilitate mutual referrals, and both were involved in community-based activities. In fact, the community leaders took an active role in guiding the program, which ultimately was funded by a grant from the Kellogg Foundation. Through negotiation and experience, they were able to define a curriculum for rural primary care that was suitable for students in public health, nursing, and medicine. Preconceived notions about the inability of rural people to understand or define their health needs greatly underestimated their interest and political abilities. They not only provided effective leadership of the program, serving as the majority of the Executive Board, but also were successful in obtaining a state appropriation for rural primary care education.

Although it’s a long way from rural primary care and Mountain City, Tennessee, to the sophisticated tertiary and quaternary care environment in which most of us work, the lessons are clear. The development of a community/provider partnership to address teen pregnancy, childhood immunization, cancer care and prevention, women’s health, and other problems will become as important a measure of success as disease management. To facilitate this, we must begin the dialogue with our colleagues in nursing and improve communication now or face increasingly frustrated patients and industry. We must also recognize that collaborative care is essential to cost-effective and high-quality outcomes, and is one of the benchmarks of JCAHO accreditation.

We must do this not because nursing needs us, but because it is the right thing to do. I began this review with considerable pessimism, but I now have a more optimistic view of the potential of our relationship. And the partnership need not result in a shift in power. As Woodrow Wilson stated, “Power consists in one’s capacity to link his will with the purpose of others, to lead by reason and a gift of cooperation.” As this millennium draws to a close, let it also see an end to the stereotypes of the omnipotent physician and subservient nurse. We have the obligation to work together to define the next level of the relationship. The goal should be a synergistic approach to the patient, who stands to gain the most from these efforts. Nursing, in turn, must do more to standardize the educational foundation of their profession, recognizing that the apprenticeship model of hospital-based programs is out of date. It will require patience, persistence, open communications, and a willingness to trust in order to bridge the barriers that have been established for so long, but it is worth the effort, and we are obliged to begin the process.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to express his gratitude to the nurses and physicians who participated in the studies, to Ms. Mary Proctor for her suggestions and contributions, and to Ms. Lucinda Cooke for administrative support.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Lazar J. Greenfield, MD, Dept. of Surgery, The University of Michigan, 2101 Taubman Center/Box 0346, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Presented at the 119th Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association on April 15, 1999, at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, San Diego, California.

References

- 1.Pember P. Southern woman’s story. St. Simon’s Island, GA: Mockingbird Books; 1959.

- 2.Ravitch MM. A century of surgery. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1981.

- 3.Driscoll VM. Legitimizing the profession of nursing: the distinct mission of the New York State Nurses Association. Albany, NY: Foundation of NYSNA; 1976.

- 4.Ethridge P. A nursing HMO: Carondelet-St. Mary’s experience. Nurs Manage 1991; 22: 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweitzer J. Tears and rage: the nursing crisis in America. Fair Oaks: Adams-Blake Publishers; 1995.

- 6.Wunderlich GS, Sloan F, Davis CK, eds. Nursing staff in hospitals and nursing homes: is it adequate? Washington: National Academic Press; 1996. [PubMed]

- 7.Keenan GM. Nurse management of conflicts with physicians in emergency rooms. Chicago: University Microfilms International, University of Chicago Health Science Center; 1994.

- 8.Baggs JG. Collaboration between nurses and physicians: what is it? Does it exist? Why does it matter? In: McCloskey JC, Grace HK, eds. Current issues in nursing, 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1994:519–524.

- 9.National Joint Practice Commission. Guidelines for establishing joint or collaborative practice in hospitals. Chicago; 1981.

- 10.Pike A. Entering collegial relationships: the demise of nurse as victim. In: McCloskey JC, Grace HK, eds. Current issues in nursing. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1994: 532–536.