Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the long-term outcome of aggressive surgery incorporating hepatic resection and systematic nodal dissection for advanced carcinoma involving the hepatic hilus.

Summary Background Data

Few long-term results are available regarding radical surgery incorporating major hepatectomy and nodal dissection.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was undertaken in 107 patients with carcinoma involving the hepatic hilus treated between 1980 and 1997. Resectional surgery was performed in 65 patients, 52 of whom underwent major hepatectomies. The effects of clinical and pathologic factors were assessed by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

Sixty percent of the patients with resectional surgery had stage IVA or IVB disease, and 92.3% of them underwent major hepatectomies. No in-hospital deaths were encountered in the 35 most recent resections, whereas there were six deaths in the early period. Resectional surgery was associated with a survival benefit, especially when resection margins were free from cancerous infiltration. The estimated 5-year survival rate after resection, including all deaths, was 34.8%; this was 51.6% when the margins were clear. Nodal involvement was documented in 44.6% of the resections. However, patients with metastases limited to the regional nodes showed a survival rate similar to that in patients without nodal involvement. Significant predictive factors for survival after resection were extension to the gallbladder, nodal status, resectional margins, histologic type, and gender.

Conclusions

The combination of major hepatectomy with systematic nodal dissection gave a good chance of prolonged survival for patients with carcinoma involving the hepatic hilus, even when the disease was advanced. Less-extensive procedures were also beneficial for less-advanced disease if clear resectional margins were secured.

Since the first description by Klatskin, 1 treatment of cholangiocarcinomas involving the hepatic hilus has been a challenge for surgeons. Due to the difficulty of definitive surgery and the relatively slow progression of the tumor, palliative procedures have long been used to treat cancers involving the hepatic hilus. 2–11 However, the results with palliative treatments have not been satisfactory. Although several reports have suggested the advantage of resectional surgery, 12–40 definitive surgery can be applied only to a minority of patients with well-localized lesions. Most patients have locally advanced disease at diagnosis and are still treated with palliative procedures. Radical surgery including major hepatectomy offers the possibility of curative resection to patients with advanced disease. However, this expected benefit must be weighed against an increased surgical risk.

Hepatic insufficiency is a common cause of postoperative death after major hepatectomy in patients with obstructive jaundice. 12,16,19,22,31–37 We have established two distinct techniques for reducing the risk of postoperative hepatic insufficiency. One is a safe and reliable method for biliary decompression, 41 and the other is a preoperative portal embolization technique. 42 Using these techniques, we have been attempting to treat advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma with radical surgery including major hepatectomy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term outcome of our aggressive approach to advanced carcinoma involving the hepatic hilus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

One hundred seven patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma (76 men, 31 women; mean age 63 years [range 36 to 79 years]) were admitted to the hepatopancreatobiliary surgery unit of the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, from 1980 to 1997. Cholangiocarcinoma was defined as cancer originating in the upper common, right, or left hepatic duct. Tumors involving the hepatic hilar region but predominantly located in the hepatic parenchyma or the gallbladder were excluded.

The treatment strategy was as follows. Initially, the location and extent of the disease were roughly evaluated by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or both. Patients with distant metastases, ascites, and extensive nodal involvement were excluded as candidates for definitive surgery, except for those with a small number of metastatic foci in the resecting liver. In patients with obstructive jaundice, biliary decompression was established principally using ultrasonographically guided percutaneous transhepatic bile drainage, 41 and cholangiograms were obtained to assess the proximal end of the obstruction. The distal end was evaluated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. While waiting for jaundice to disappear, further investigation was carried out using angiography and thin-slice or helical computed tomography with a bolus injection of a contrast medium to obtain detailed information about local extension of the disease. To decrease the risk of postoperative liver insufficiency, preoperative portal embolization was performed in patients who were candidates for major hepatectomies in which >60% of the liver parenchyma was to be resected. Resectional surgery was planned 2 to 3 weeks after portal embolization. All attempts at definitive surgery were carried out when the serum level of total bilirubin decreased to <5 mg/dl.

Our standard resectional procedures consisted of hepatectomy, resection of the extrahepatic bile duct, and dissection of the regional lymph nodes. The following terms were used to describe the extent of hepatectomy—right or left hepatectomy: hemihepatic resection; left trisegmentectomy: left hepatectomy combined with resection of Couinaud segments V and VIII 43; extended right or left hepatectomy: hepatectomies more extended than hemihepatic resection and less extended than trisegmentectomy. Major hepatectomy, in which more than a hemihepatic lobe was resected, was commonly employed. However, either the extent of hepatic resection was restricted to include only the hilar region or no hepatectomy was performed when the patient had profound hepatic dysfunction or was in poor general condition. The hepatic lobe to be resected was principally determined according to the predominant site of the lesion. Extended right hepatectomy including resection of the entire caudate lobe and the inferior part of the left medial segment was carried out when the dominant site of involvement was the right hepatic or upper common bile duct. Extended left hepatectomy including resection of the spigelian lobe and the right hilar region was performed in patients in whom the left hepatic duct was predominantly involved. Lymph nodes and connective tissue in the hepatoduodenal ligament, posterior to the upper portion of the pancreatic head, and around the common hepatic artery were dissected in an en bloc fashion.

Every cut end of the bile duct was submitted for frozen-section examination. If the tissue was positive for cancer cells, an additional resection in an attempt to secure a clear margin was carried out whenever technically possible.Concomitant pancreatoduodenectomy was performed only when the microscopic spread of cancer cells into the intrapancreatic bile duct was the single obstacle to curative resection.

In preparing sections of a fixed specimen, surgeons assisted pathologists for the correct identification of complicated resectional margins. Three pathologists confirmed each histologic judgment. TNM categories and stage of disease were classified according to the criteria of the International Union Against Cancer (fifth edition).

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. The relations among categorical variables were tested with chi square analysis. Survival rate was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, including deaths from all causes. Univariate comparisons of survival curves were made with the log-rank test. Associations were considered significant if p ≤ 0.05. All the variables that were significantly associated with patient survival were included in a subsequent stepwise multivariate analysis. The Cox proportional hazard model with a likelihood ratio test was used for this purpose. Variables were eliminated from the model when significance exceeded 0.05 in a likelihood ratio test. In comparing the effect of nodal involvement, lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament, posterior to the upper half of the pancreatic head, and around the common hepatic artery were considered regional.

RESULTS

Treatments

Surgical intervention was attempted in 89 patients. Of these, resectional surgery was performed in 65 patients (73.0%). Major hepatic resections were performed in 52 patients (80.0% of resections). These consisted of 31 extended left hepatectomies, 2 left trisegmentectomies, and 19 extended right hepatectomies. Limited hepatic resections were performed in five patients, and eight patients underwent resections without hepatectomy. Total or partial resection of the caudate lobe was performed in 50 (96.2%) of the major hepatectomies and 4 (80.0%) of the limited hepatic resections. Concomitant procedures included resection and reconstruction of the portal vein in three patients, that of the right hepatic artery in three, and pancreatoduodenectomy in three. Nonsurgical treatments were selected in 18 patients, and nonresectional surgeries (14 bypass and/or drainage operations, 8 exploratory laparotomies, and 2 intraoperative irradiations) were performed in 24 because of far-advanced disease. The overall resectability rate was 61.2%. Biliary decompression was established in 46 patients (70.8%) before resectional surgery, 87.0% of them with percutaneous transhepatic bile drainage. According to the criteria mentioned above, preoperative portal embolization was used in 100% before left trisegmentectomy, in 78.9% before extended right hepatectomy, and in 9.7% before extended left hepatectomy. Unilobar atrophy of the resecting lobe secondary to obstruction of the lobar portal branch was observed in seven patients. Portal embolization was not carried out in these patients. Surgical time, blood loss, and whole blood transfusion in procedures including major hepatectomy were 648 ± 155 minutes, 1368 ± 860 ml, and 529 ± 789 ml, respectively, and those in the other resectional procedures were 705 ± 245 minutes, 1299 ± 735 ml, and 497 ± 630 ml, respectively. The incidence of intraoperative whole blood transfusion was 46.2% in major hepatectomies and 53.8% in limited resections.

Morbidity and Mortality Rates

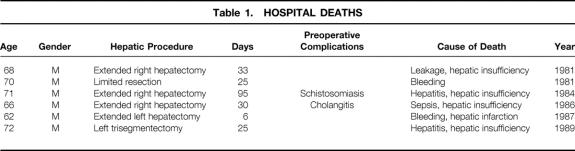

Complications occurred in 24 patients (36.9%) with resectional surgery. Bile or anastomotic leakage was the most common complication (n = 13; 20.0%), followed by hepatic insufficiency (n = 7; 10.8%), intraabdominal abscess (n = 3; 4.6%), liver abscess (n = 3; 4.6%), gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 3; 4.6%), intraabdominal bleeding (n = 3; 4.6%), and sepsis (n = 2; 3.1%). As a result of complications, six patients died in the hospital (four within 30 days) after resectional surgery, accounting for a mortality rate of 9.2% (6.2% within 30 days) (Table 1). All of the hospital deaths occurred in the 1980s. Hepatic insufficiency was a major cause of death. In two patients, the onset of posttransfusion hepatitis altered the uneventful postoperative course. In another patient, this developed as a sequela of a persistent septic state after a rescue operation for uncontrollable cholangitis. However, no hospital death occurred among the 35 consecutive recent resections (31 in the 1990s) including 28 major hepatectomies, despite the increased incidence of advanced disease in the 1990s. The proportion of stage IV disease in patients with resectional surgery was 52.9% (n = 18) in the 1980s and 67.7% (n = 21) in the 1990s.

Table 1. HOSPITAL DEATHS

Overall Survival

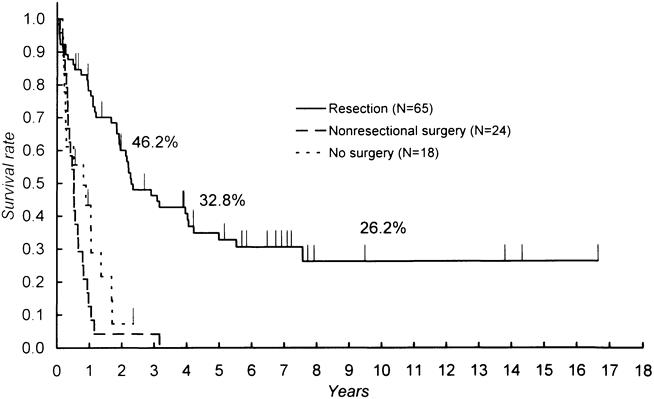

Patient survival with respect to the type of treatment is shown in Figure 1. Survival time was counted from the day of surgery in patients with surgical treatment and from the day of admission in those without surgery. The mean and median durations of survival in patients treated by resectional surgery were 73.6 and 28.0 months, with 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates of 78.2%, 32.8%, and 26.2%, respectively. In contrast, most of the patients without resectional surgery died within 2 years. This difference in the probability of survival was significant between patients treated with resectional surgery and those without resection. Nonresectional surgery did not appear to offer any survival benefit over nonsurgical palliation.

Figure 1. Comparison of survival among patients with resection, nonresectional surgery, and nonsurgical procedures. Survival was counted from the day of admission for nonsurgical procedures and from the day of surgery in others. Significant differences were found between resection and nonresectional surgery (p < 0.0001) and between resection and no surgery (p < 0.0001).

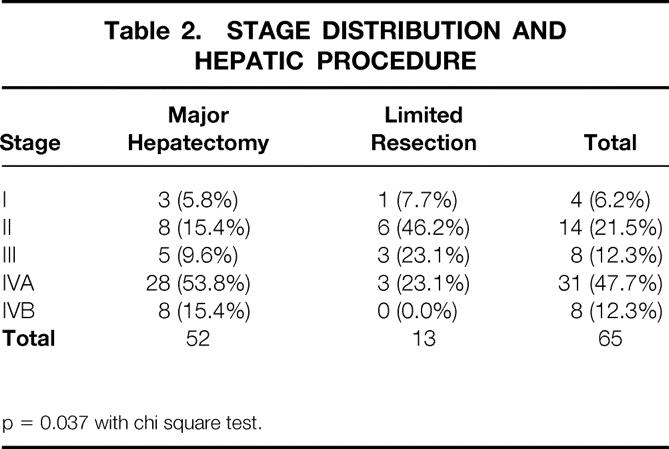

Stage Distribution and Type of Resection

Most of the patients who underwent resectional surgery had advanced disease, and 60.0% were classified as having stage IVA or IVB disease (Table 2). Major hepatic resection was carried out in 92.3% of patients with stage IVA or IVB disease. Limited hepatic resections and resections without hepatectomy were used in patients with less-advanced disease. The stage distribution varied significantly (p = 0.037) with the procedure applied.

Table 2. STAGE DISTRIBUTION AND HEPATIC PROCEDURE

p = 0.037 with chi square test.

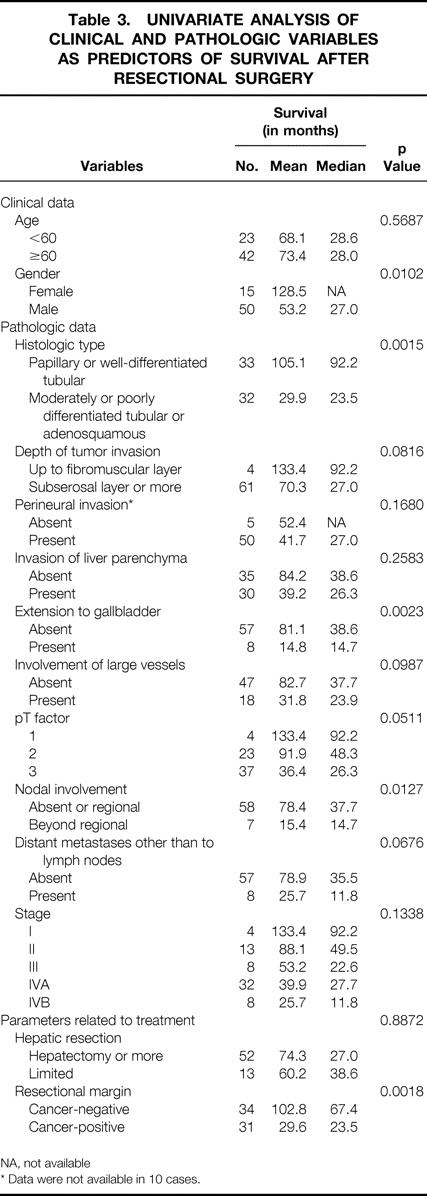

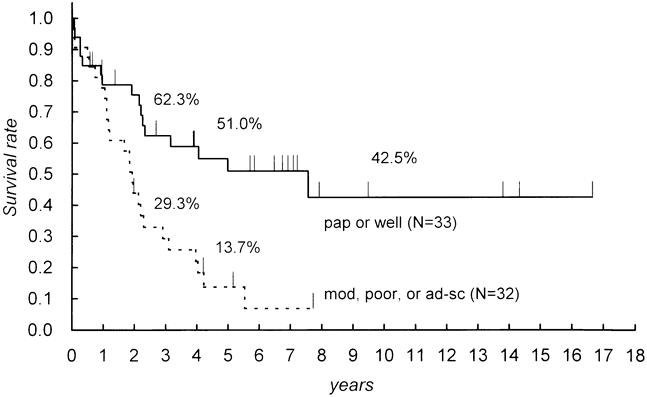

Histologic Type

The histologic type of the lesions reflects the predominant type. One patient (1.5%) had adenosquamous carcinoma, and the other 64 patients (98.5%) with resectional surgery had adenocarcinomas. Papillary adenocarcinomas were found in 9.2% of patients, and the other cases were tubular adenocarcinomas: well differentiated in 41.5%, moderately differentiated in 33.8%, and poorly differentiated in 13.8%. Patients with papillary and well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma had significantly better survival than those with the other histologic types (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 3. UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF CLINICAL AND PATHOLOGIC VARIABLES AS PREDICTORS OF SURVIVAL AFTER RESECTIONAL SURGERY

NA, not available

* Data were not available in 10 cases.

Figure 2. Comparison of survival according to the predominant histologic type. A significant difference was found between papillary or well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and the others (p = 0.0015). pap, papillary; well, well-differentiated tubular; mod, moderately differentiated tubular; poor, poorly differentiated tubular; ad-sq, adenosquamous.

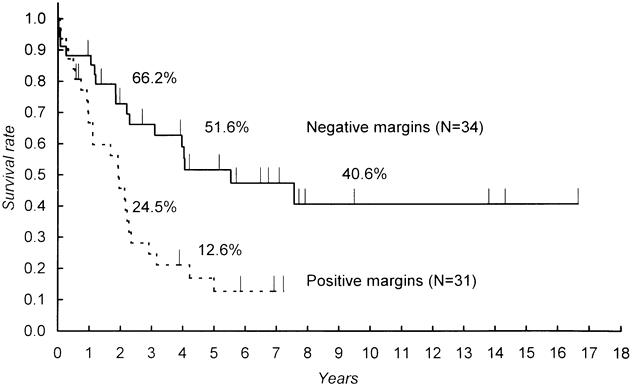

Resectional Margins

An extensive histologic survey frequently found the microscopic extension of tumor cells in and around the cut end of the bile duct and in the dissection margin of major vessels. Only 34 cases (52.3%) were judged to have completely free margins. The incidence of positive margins in major hepatectomies was 44.2%; that in limited resections was 61.5%. However, this difference was not statistically significant. Particularly good results were observed in patients with completely free resectional margins. The 5-year survival rates for patients with negative and positive resectional margins were significantly different (p = 0.0018) at 51.6% and 16.8%, respectively (Fig. 3). Although patients with a positive margin had worse survival rates than those with a negative margin, they were still significantly better than those in patients with nonresectional surgery (p < 0.0001) or nonsurgical procedures (p = 0.045).

Figure 3. Comparison of survival between resections with and without marginal involvement. A significant difference was found (p = 0.0018).

Nodal Status

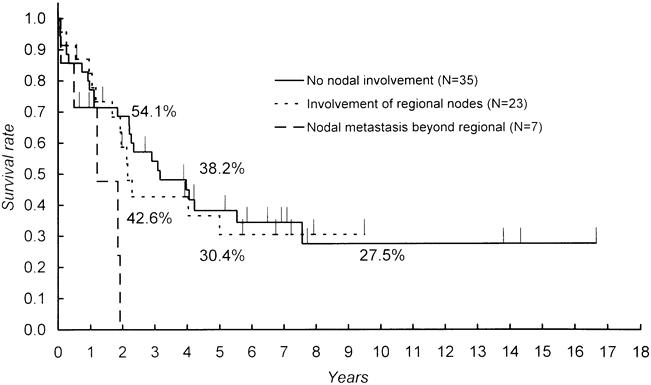

Metastases to lymph nodes were documented in 29 patients, accounting for 44.6% of those with resectional surgery. These were classified as regional (n = 23) or beyond regional (n = 6) according to the definition given above. The mean and median durations of survival were 78.8 and 38.6 months in patients without nodal involvement, 51.7 and 26.3 months in those with metastases limited to the regional nodes, and 15.4 and 14.7 months in those with nodal involvement beyond regional nodes, respectively. Whereas the survival curves of the first two patient groups were similar (Fig. 4), the last group had significantly worse survival than the other groups.

Figure 4. Comparison of survival according to nodal status. Significant differences were found between no involvement and beyond regional (p = 0.0211) and between regional and beyond regional (p = 0.0190).

Distant Metastases Other Than to Lymph Nodes

Eight patients had small metastatic foci in sites other than lymph nodes—five in the liver, two in the lesser omentum, and one in the duplicated intestine. These lesions could not be detected before surgery, and a definitive diagnosis was made after resection. One of the patients with hepatic metastasis lived 3 years 8 months, and one of those with an omental deposit is alive and well 7 years 7 months after surgery.

Univariate Analysis

The results of a univariate analysis for the relations between clinical, pathologic, and interventional variables and patient survival after resectional surgery are shown in Table 3. Based on the result mentioned above, the effect of nodal status was compared between the patient group without nodal involvement or with involvement limited to the regional nodes and that with metastases beyond regional nodes. Factors that significantly predicted survival were histologic type of the lesion, clearance of resectional margins, transmural extension to the gallbladder, patient gender, and nodal status.

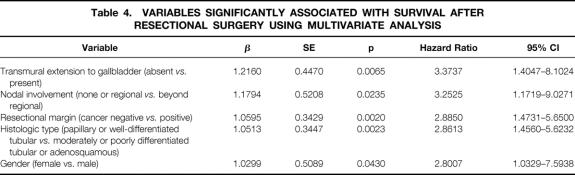

Multivariate Analysis

The variables that were significant by univariate analysis were subsequently analyzed using the Cox proportional hazard model. The factors that were significantly related to patient survival were the same as those indicated by the univariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4. VARIABLES SIGNIFICANTLY ASSOCIATED WITH SURVIVAL AFTER RESECTIONAL SURGERY USING MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

DISCUSSION

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is unique among cancers of the extrahepatic bile duct with regard to the difficulty of radical resection. Recently, many authors have advocated surgical resection instead of palliative procedures. 12–40 However, most of them have provided insufficient information concerning the effect of extensive surgery for the treatment of advanced disease. This report reviews our attempt to treat hilar cholangiocarcinoma with extensive procedures including major hepatectomy, caudate lobectomy, and systematic nodal dissection.

The overall in-hospital mortality rate of 9.2% in resectional surgery was not satisfactory but was comparable to those in previous reports. 31–38 All of the in-hospital deaths occurred in the 1980s. A common cause of death was hepatic insufficiency that developed after complications that were considered to be recoverable, such as cholangitis, hepatitis, and anastomotic leakage. Uncontrolled cholangitis was dangerous for patients with major hepatectomy. Resection of an infected hepatic lobe was attempted to relieve septic cholangitis in two patients; however, a persistent septic state complicated the postoperative course and led to the death of one of these patients. Definitive surgery had to be postponed until the infectious state subsided. In two patients, posttransfusion hepatitis triggered the onset of hepatic insufficiency. No such episodes have been encountered since a system for screening blood products for contamination with hepatitis C virus was established in 1990. It is thought that hepatic functional deterioration provoked by obstructive jaundice continues for a long time even after biliary decompression, and that a perioperative inflammatory episode is hazardous for patients with minimal hepatic functional reserve. However, no hospital deaths were encountered in the 10 most recent years. We have performed a large number of hepatic resections to treat hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. 44 The general improvement of our technique and knowledge concerning hepatic resection for patients with a compromised liver, along with our experience in the early period, has contributed to the enhanced safety of major hepatectomy complicated with obstructive jaundice. This achievement is also reflected in the excellent short-term results reported at Shinshu University, which has a technical background similar to ours. 39,40 Although we might have initially overestimated the advantageous effect of portal embolization, the risk of extensive surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, although not negligible, can be controlled.

In the present study, we compared all resectional surgeries with nonresectional treatments because the judgment of curative intent was ambiguous. Nonetheless, resectional surgery was shown to offer a clear survival benefit. Despite the large proportion of patients with advanced disease, the survival rate was far better in patients who were treated with resectional surgery than in those who received nonresectional treatments. Consequently, the benefit of extensive surgery for patients with advanced disease is estimated. Although previous reports have commonly noted the advantage of resectional surgery, the majority of these have been based on a small number of patients treated with radical resection.

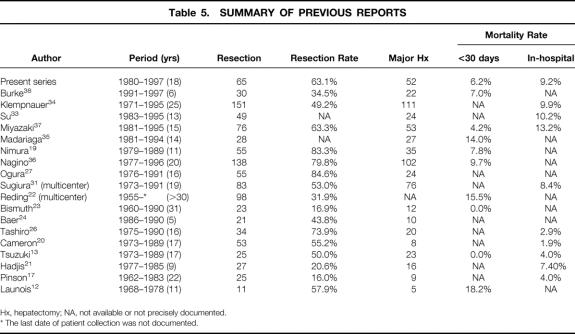

Only four single-center series, including the present study and excluding those with overlapping patients, have included >50 patients treated with major hepatectomy 34,36,37 (Table 5). Klempnauer et al 34 resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in 151 patients, 73.5% of them with major hepatectomy. Stage IV disease constituted 59.6% of their patients. The overall 5-year survival rate was 25.6%, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 9.9%. The relatively good results in treating a large number of patients with advanced disease were consistent with ours. Miyazaki et al 37 reported the results of 76 cases of resectional surgery, 69.7% of which were with major hepatectomy. The in-hospital mortality rate was 13.2% and the 5-year survival rate was 26%. Their results were similar to those of Klempnauer et al. However, the distribution of the stage of disease was not provided. Madariaga et al 35 reported their results with a more aggressive approach—78% of their 28 patients had stage IV disease. However, their results were disappointing: the 5-year survival rate was 8.0% and the mortality rate within 30 days was 14.0%. Considering our experience in the early period, this may be attributable to insufficient experience with extensive surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Table 5. SUMMARY OF PREVIOUS REPORTS

Hx, hepatectomy; NA, not available or not precisely documented.

* The last date of patient collection was not documented.

Three reports have documented 5-year survival rates greater than that in the current series. 17,19,38 In one of these reports, the survival rate was 37.8%. 19 However, only patients with curative resection were included in the calculation. Recently, the results of 124 hepatic resections were reported by the same authors, again with survival rates calculated only after curative resections, 36 and the rate at 5 years fell to 25.8%. In another report, the 5-year survival rate in 30 patients with potentially curative resection was as high as 45%. 38 However, this excellent value will have to be reassessed in the future because of the relatively short study period (6 years). In the other report, the 5-year survival rate in 25 resections was 35%. 17 A low resection rate of 16% and the infrequent application of major hepatectomy (36.0% of resections) suggest that this result reflects the treatment of less-advanced disease.

The present study showed that the independent predictive factors for the survival of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma undergoing resectional surgery were transmural extension to the gallbladder, nodal status, clearance of resectional margins, histologic type of the lesion, and patient gender. Among these, clearance of resectional margins and nodal status were closely related to the strategy of surgical treatment. The extent of hepatic resection was not a significant factor; however, it was closely related to the extent of the disease. Sixty percent of our patients with resectional surgery had stage IV disease, and major hepatectomy was carried out in 92.3% of them. The similar survival and significantly different stage distribution in patients with and without major hepatectomies support the use of major hepatectomies for patients with advanced disease. We consider that caudate lobectomy is also an essential component of radical surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, as mentioned in previous reports, 13,15,18,19,26,31 and we believe that this contributed to the good long-term results in our patients treated with resectional surgery. However, we could not assess the effects of caudate lobectomy because it was incorporated in 92.6% of major hepatic resections.

The particularly good results in patients with clear resectional margins demonstrate the importance of microscopic curative resection to ensure better survival. However, resectional margins were frequently positive for cancer cells despite our intent to enhance curability by incorporating major hepatectomy. Although the extent of the lesion could be estimated with limited accuracy, 45,46 the invasive nature of the lesion and the anatomic complexity of the hilar region hindered us from securing sufficient surgical margins in patients with advanced disease. The frequent involvement of resectional margins was a common problem in most of the previous reports. 12–18,23,24,26,27,31–33,35,47 Although some authors 19,34,36–38 reported an exceptionally high rate of curative resection, their patients with resectional surgery mostly did not show better survival than ours. This suggests the difficulty and wide interinstitutional differences in the histologic evaluation of surgical margins in this disease. Considering that resection with positive margins still offers a significant benefit over nonresectional treatment, attempted macroscopically curative resection would be justified.

Adjuvant treatment is expected to confer a benefit in light of the high possibility of microscopic or occult residue of cancer cells around the resectional margins. Although some authors have recommended adjunctive radiotherapy, 30,47 its effect is controversial. 48

Nodal status was a significant predictive factor for survival, as mentioned in previous reports. 22,25,29,31,32,34 However, in the present study the survival of patients with metastases limited to regional lymph nodes was similar to that in patients without nodal involvement. This result strongly supports the notion that the incorporation of systematic nodal dissection in our resectional procedures is beneficial. A prospective trial that is controlled for technical quality and the accurate localization of metastatic nodes would be required to obtain reliable results. However, our results are encouraging. We believe that systematic nodal dissection should be incorporated in the radical surgery until its value is established.

In the present study, transmural extension to the gallbladder was a significant predictor for survival. However, it is unlikely that involvement of the gallbladder itself is of primary importance for patient survival. We consider that this factor represented the invasive nature of the cancer in our series. Lesions involving the gallbladder were commonly accompanied by the diffuse infiltration of cancer cells into the connective tissue in the hepatoduodenal ligament. Other factors, such as perineural invasion and the involvement of major vessels, may have a similar meaning and have been discussed with various results. 25,27,28,33,34 The pT factor, as a general index of progression of the primary tumor, also correlated with patient survival, although significance was not established. The ability of transmural extension to the gallbladder to represent the invasive nature of the tumor is uncertain because no other reports have focused on it. It would be interesting to evaluate this factor in future investigations.

Better patient survival with more differentiated carcinoma has been commonly noted in previous reports and was reconfirmed in the present study. The proportion of well-differentiated carcinoma was relatively high in the current series, although other factors that reflect the aggressiveness of the tumor were comparable with those in other reports. This might result from the different criteria used by pathologists to classify differentiation of a tumor, because cholangiocarcinoma is commonly composed of components with varying degrees of differentiation.

Different survival rates by gender have not been previously emphasized in cholangiocarcinoma. In the present series, women lived longer than men after resectional surgery. A higher 5-year survival rate in women was also observed in a previous study, 34 but this difference was not significant. The effect of sex hormones on survival has been suggested in various neoplasms, including carcinomas of the digestive tract, 49,50 and trials of hormonal therapy have been undertaken. 51 Our results suggest that a similar approach may be useful in cholangiocarcinoma.

In conclusion, the combination of major hepatectomy with resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and the caudate lobe gives a good chance of prolonged survival for patients with bile duct carcinoma involving the hepatic hilus, even when the disease is advanced. However, care should be taken regarding the latent risk of hepatic insufficiency. Safety would be enhanced with the proper use of precautionary measures such as controlling preexisting cholangitis, biliary decompression, and preoperative portal embolization. Less-extensive procedures are also beneficial for patients with less-advanced disease if clear resectional margins are secured. Systematic dissection of regional lymph nodes should be performed because metastases are frequent and manageable.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Tomoo Kosuge, MD, Dept. of Surgery, National Cancer Center Hospital, 5-1-1, Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan.

Supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

Accepted for publication April 9, 1999.

References

- 1.Klatskin G. Adenocarcinoma of the hepatic duct at its bifurcation within the porta hepatis: an unusual tumor with distinctive clinical and pathologic features. Am J Med 1965; 38:241–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guthrie CM, Haddock G, De Beaux AC, et al. Changing trends in the management of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 1993; 80:1434–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuvshinoff BW, Armstrong JG, Fong Y, et al. Palliation of irresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma with biliary drainage and radiotherapy. Br J Surg 1995; 82:1522–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu CL, Lo CM, Lai EC, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic endoprosthesis insertion in patients with Klatskin tumors. Arch Surg 1998; 133:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Praderi RC. Twelve years’ experience with transhepatic intubation. Ann Surg 1974; 179:937–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terblanche J, Saunders SJ, Louw JH. Prolonged palliation in carcinoma of the main hepatic duct junction. Surgery 1972; 71:720–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan RC, Faris TD. Hepaticojejunostomy. Modified Longmire operation for bile duct carcinoma. Am J Surg 1967; 114:722–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarnagin WR, Burke E, Powers C, et al. Intrahepatic biliary enteric bypass provides effective palliation in selected patients with malignant obstruction at the hepatic duct confluence. Am J Surg 1998; 175:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schima W, Prokesch R, Osterreicher C, et al. Biliary Wallstent endoprosthesis in malignant hilar obstruction: long-term results with regard to the type of obstruction. Clin Radiol 1997; 52:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowling TE, Galbraith SM, Hatfield AR, et al. A retrospective comparison of endoscopic stenting alone with stenting and radiotherapy in non-resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Gut 1996; 39:852–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritz P, Brambs HJ, Schraube P, et al. Combined external-beam radiotherapy and intraluminal high-dose-rate brachytherapy on bile duct carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1994; 29:855–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Launois B, Campion JP, Brissot P, et al. Carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. Surgical management and the case for resection. Ann Surg 1979; 190:151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuzuki T, Ogata Y, Iida S, et al. Carcinoma of the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts. Arch Surg 1983; 118:1147–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumgart LH, Hadjis NS, Benjamin IS, et al. Surgical approaches to cholangiocarcinoma at confluence of hepatic ducts. Lancet 1984; 1:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizumoto R, Kawarada Y, Suzuki H. Surgical treatment of hilar carcinoma of the bile duct. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1986; 162:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bengmark S, Ekberg H, Evander A, et al. Major liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1988; 207:120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinson CW, Rossi RL. Extended right hepatic lobectomy, left hepatic lobectomy, and skeletonization resection for proximal bile duct cancer. World J Surg 1988; 12:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuzuki T, Ueda M, Kuramochi S, et al. Carcinoma of the main hepatic duct junction: indications, operative morbidity and mortality, and long-term survival. Surgery 1990; 108:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatic segmentectomy with caudate lobe resection for bile duct carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. World J Surg 1990; 14:535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Zinner MJ, et al. Management of proximal cholangiocarcinomas by surgical resection and radiotherapy. Am J Surg 1990; 159:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadjis NS, Blenkharn JI, Alexander N, et al. Outcome of radical surgery in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 1990; 107:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reding R, Buard JL, Lebeau G, et al. Surgical management of 552 carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts (gallbladder and periampullary tumors excluded). Results of the French Surgical Association Survey. Ann Surg 1991; 213:236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1992; 215:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baer HU, Stain SC, Dennison AR, et al. Improvements in survival by aggressive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1993; 217:20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhuiya MR, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Clinicopathologic factors influencing survival of patients with bile duct carcinoma: multivariate statistical analysis. World J Surg 1993; 17:653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tashiro S, Tsuji T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Prolongation of survival for carcinoma at the hepatic duct confluence. Surgery 1993; 113:270–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogura Y, Mizumoto R, Tabata M, et al. Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the hepatic duct confluence: analysis of 55 resected carcinomas. World J Surg 1993; 17:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Childs T, Hart M. Aggressive surgical therapy for Klatskin tumors. Am J Surg 1993; 165:554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, et al. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg 1993; 128:871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoenthaler R, Phillips TL, Castro J, et al. Carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. The University of California at San Francisco experience. Ann Surg 1994; 219:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugiura Y, Nakamura S, Iida S, et al. Extensive resection of the bile ducts combined with liver resection for cancer of the main hepatic duct junction: a cooperative study of the Keio Bile Duct Cancer Study Group. Surgery 1994; 115:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washburn WK, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL. Aggressive surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg 1995; 130:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, et al. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1996; 223:384–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, et al. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15:947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, et al. Liver resection for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinomas: a study of 62 cases. Ann Surg 1998; 227:70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagino M, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Segmental liver resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1998; 45:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, et al. Aggressive surgical approaches to hilar cholangiocarcinoma: hepatic or local resection? Surgery 1998; 123:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg 1998; 228:385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawasaki S, Makuuchi M, Miyagawa S, et al. Radical operation after portal embolization for tumor of hilar bile duct. J Am Coll Surg 1994; 178:480–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyagawa S, Makuuchi M, Kawasaki S. Outcome of extended right hepatectomy after biliary drainage in hilar bile duct cancer. Arch Surg 1995; 130:759–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makuuchi M, Bandai Y, Ito T, et al. Ultrasonically guided percutaneous transhepatic bile drainage: a single-step procedure without cholangiography. Radiology 1980; 136:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makuuchi M, Thai BL, Takayasu K, et al. Preoperative portal embolization to increase safety of major hepatectomy for hilar bile duct carcinoma: a preliminary report. Surgery 1990; 107:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Couinaud C. Etude anatomiques et chirugicales. Paris: Masson; 1957:400–409.

- 44.Kosuge T, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, et al. Long-term results after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: experience of 480 cases. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1993; 40:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogura Y, Takahashi K, Tabata M, et al. Clinicopathological study on carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct with special focus on cancer invasion on the surgical margins. World J Surg 1994; 18:778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakamoto E, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. The pattern of infiltration at the proximal border of hilar bile duct carcinoma: a histologic analysis of 62 resected cases. Ann Surg 1998; 227:405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todoroki T, Fukuda Y, Kawamoto T, et al. Long-term survivors after salvage surgery combined with radiotherapy for recurrence of stage IV main hepatic duct cancer—report of two cases. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1993; 40:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pitt HA, Nakeeb A, Abrams RA, et al. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Postoperative radiotherapy does not improve survival. Ann Surg 1995; 221:788–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenway BA. Carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas: a sex hormone-responsive tumour? Br J Surg 1987; 74:441–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Holmberg L, et al. The effect of female sex hormones on cancer survival. A register-based study in patients younger than 20 years at diagnosis. JAMA 1990; 263:2189–2193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenway BA. Effect of flutamide on survival in patients with pancreatic cancer: results of a prospective, randomised, double-blind placebo controlled trial. Br Med J 1998; 316:1935–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]