Abstract

Objective

To evaluate prospectively the effect of bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy on pancreatic pain and function.

Summary Background Data

Severe pain is often the dominant symptom in pancreatic disease, despite a wide variety of methods used for symptom relief. Refinement of thoracoscopic technique has led to the introduction of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy in the treatment of pancreatic pain.

Methods

Forty-four patients, 23 with pancreatic cancer and 21 with chronic pancreatitis, were included in the study and underwent bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. Effects on pain (visual analogue scale) and pancreatic function (standard secretin test, basal serum glucose, plasma insulin, and C-peptide) were measured.

Results

Four patients (9%) required thoracotomy because of bleeding. There were no procedure-related deaths. The mean duration of follow-up was 3 months for cancer and 43 months for pancreatitis. Pain relief was evident in the first postoperative week and was sustained during follow-up, the average pain score being reduced by 50%. All patients showed a decrease in consumption of analgesics. Neither endocrine nor exocrine function was adversely affected by the procedure.

Conclusions

Bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy is beneficial in the treatment of pancreatic pain and is not associated with deterioration of pancreatic function.

Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer are both associated with severe pain and impaired pancreatic function. Ideal treatment options would have a limited risk of drug addiction and would leave the functional capacity of the gland unaffected. Recent advances in laparoscopic technique also include developments in the field of thoracoscopy. The first report on successful thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy for pancreatic pain was published as recently as 1993. 1 The rationale for neurotomy in this symptom is based on the fact that sensory nerves from the pancreas run along the hepatic, splenic, and superior mesenteric arteries to the semilunar ganglion, where they become incorporated in the greater and lesser splanchnic nerves, which arise from the 5th to the 11th thoracic ganglia on both sides of the vertebrae. Afferent sympathetic fibers follow the same route, whereas extrinsic parasympathetic innervation is supplied by the vagus. Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy has targeted the greater splanchnic nerve. 1

It is well established that exocrine pancreatic secretion is under neurohormonal control. 2 Neurotransmitters and hormones interact in a complex manner, so it is difficult to differentiate the relative influence of each factor. Truncal vagotomy and the administration of atropine dramatically decrease the pancreatic bicarbonate and enzyme responses to hormonal stimulation and to intraduodenal fat, protein, or acid. 3 There are suggestions that the sympathetic nervous system inhibits pancreatic exocrine secretion. 4,5 Splanchnicectomy by retroperitoneal, intraperitoneal, and transhiatal approaches, transthoracic left splanchnicectomy combined with truncal vagotomy, and percutaneous celiac block have been used in the past to treat pancreatic pain. 6 Pain relief of 70% to 90% has been reported, although the duration of the effect has been limited generally to 3 to 4 months. 7–9 This prospective study was designed to evaluate the effect of bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy (BTS) on pancreatic pain and function in patients with pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between December 1993 and December 1998, 44 patients, 21 with chronic pancreatitis and 23 with pancreatic cancer, underwent BTS because of pain.

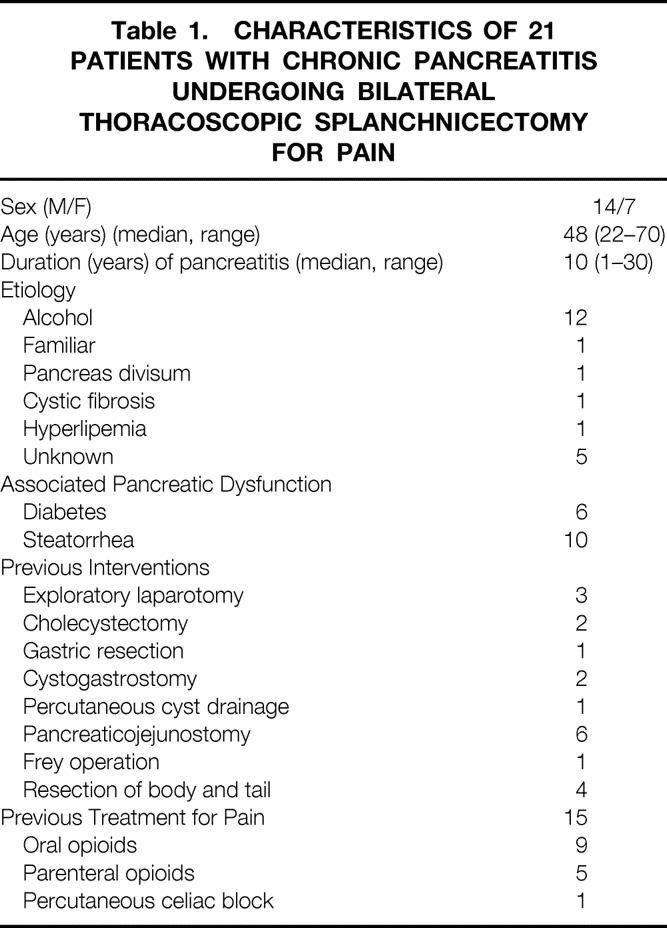

The patients with chronic pancreatitis had a median age of 48 years. All required pancreatic enzyme substitution. In most of them the disease was caused by alcohol, and the mean duration of pancreatitis before BTS was 10 years. Two thirds of the patients required opioid treatment, mostly oral, but 5/21 received parenteral opioids (Table 1). The diagnosis was verified by ultrasonography, computed tomography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, a secretin test, or histologic examination of pancreatic tissue. Previous surgical treatments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. CHARACTERISTICS OF 21 PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC PANCREATITIS UNDERGOING BILATERAL THORACOSCOPIC SPLANCHNICECTOMY FOR PAIN

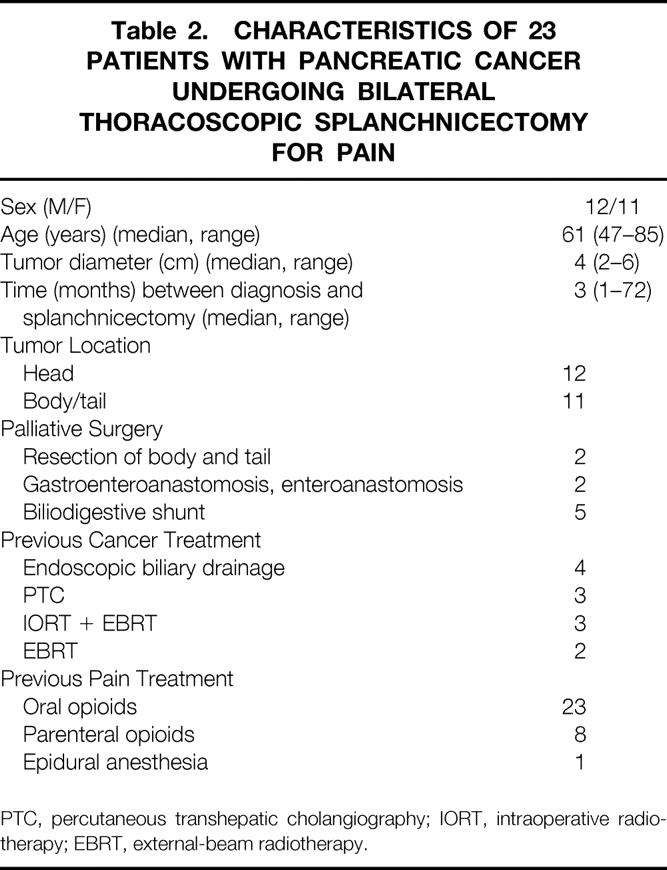

The median age of the patients with pancreatic cancer was 61 years. In all patients the diagnosis was verified histologically or cytologically. In 11/23 patients, the lesion was located in the body/tail part of the gland, with a mean tumor diameter of 4 cm. The median time from diagnosis to BTS was 3 months. None of the patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy, but two had had palliative resection of the body and tail. Other preoperative interventions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF 23 PATIENTS WITH PANCREATIC CANCER UNDERGOING BILATERAL THORACOSCOPIC SPLANCHNICECTOMY FOR PAIN

PTC, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography; IORT, intraoperative radiotherapy; EBRT, external-beam radiotherapy.

The reason for performing BTS was the presence of intractable pain resistant to all other treatment modalities available in our department. Morphologic data such as diffuse or segmental pancreatitis, dilated ducts, tumor location, or nutritional status were not considered to be determining criteria.

Surgical Technique

The BTS procedure was performed with the patient in prone position on the operating table, without support beneath the epigastric and upper sternal regions, to enable respiratory excursion of the chest walls. Double-lumen endotracheal intubation was used for general anesthesia, allowing single-lung ventilation. A small trocar was introduced through a stab incision in the intercostal space immediately below the inferior angle of the scapula (usually the fifth intercostal). Air was allowed to leak in to create a pneumothorax, and ventilation of that lung was stopped. Carbon dioxide was insufflated, if necessary, to provide an adequate working space inside the thoracic cavity. Only two ports on each side were used. The optical cannula (10.0 mm) replaced the first trocar, and another 5.5-mm operating cannula was inserted under direct vision in the next or second-next intercostal space below the optical cannula. A 30° forward oblique telescope was chosen. A duck-bill grasper and an electrosurgical hook were used through the operating cannula.

Adhesions between the lung and the parietal pleura were cut with the electrosurgical hook. The sympathetic nerves and their branches were identified. The hook was used to make a small incision in the parietal pleura on both sides of the nerves or their branches, ≥10 mm from the sympathetic chain. The nerves or their branches were then lifted up with the hook, mobilized and freed for a distance of approximately 10 mm, and then transected so that the ends were seen to be well retracted from each other. The uppermost branch was usually found on the neck of the sixth rib. Because this branch was the easiest to identify, the procedure usually started at this level, and then the other branches were transected, one by one, along the sympathetic trunk. The trunk itself was not transected to minimize the risk of extensive visceral denervation. After completing the transection down to the costophrenic recess and ensuring there was no bleeding, a small chest tube (12F) was inserted through the lower cannula incision. The procedure, which usually lasted 15 to 20 minutes, was repeated on the other side. A chest x-ray was performed during recovery from anesthesia. In most patients the chest tubes were removed after 6 to 8 hours. In uncomplicated cases, the patient was discharged from the hospital on the first postoperative day.

Assessment of Pain

The effects on pain relief were assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS). The patients were asked to assess the severity of pain on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 = no pain at all, 10 = unbearable pain). Pain intensity was measured before BTS and 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, and 2, 3, and 4 years after BTS. (The intensity of pain is given as the mean of VAS points per day during the previous week.) Consumption of analgesics was documented at the same intervals. The patients with chronic pancreatitis were assessed by one of the authors; a specially assigned nurse assessed the patients with pancreatic cancer.

Assessment of Pancreatic Function

Exocrine pancreatic function was studied by a standard secretin test with a tube placed in the third part of the duodenum for collection of intestinal juice. 10 After a 10-minute basal period, 1 CU/kg of secretin (Ferring AB, Malmö, Sweden) was administered intravenously, and the sampling was continued for two 15-minute periods. Bicarbonate in the duodenal juice aliquots was determined titrimetrically. In our laboratory, the normal bicarbonate concentration is >80 mmol/l, 50 to 80 mmol/l is equivocal, and <50 mmol/l is consistent with pancreatic insufficiency. Serum amylase and lipase activities were measured. Basal serum values of glucose, insulin, 11 C-peptide, 12 glucagon, 13 gastrin, 14 and pancreatic polypeptide 15 were measured by radioimmunoassay (Euro-Diagnostica AB, Malmo, Sweden; RIA kit) at the same time intervals as for the secretin test. Fifteen patients (10 chronic pancreatitis, 5 pancreatic cancer) were studied by the secretin test, 1 day before and 2 weeks after BTS.

Statistical Analysis

Statistically significant differences between paired laboratory results were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Correlations were calculated by the chi square test. Probability values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

No patient was lost to follow-up. For patients with pancreatic cancer, the median duration of follow-up was 4 months and the mean was 3 months. The corresponding figures for patients with chronic pancreatitis were 42 and 43 months.

The median number of cut nerves was 7 (range 3 to 13). There was no correlation between the number of cut nerves and pain relief as analyzed at 1 week (p = 0.61), 1 month (p = 0.21), or 3 months (p = 0.51).

The hospital death rate was 0%. Four patients (9%) required thoracotomy for bleeding the afternoon of the day of surgery, two from arteries close to a splanchnic nerve and two from the larger port incision. All four patients recovered uneventfully. Another patient had transient pain at the incision site for the larger thoracoscopy port.

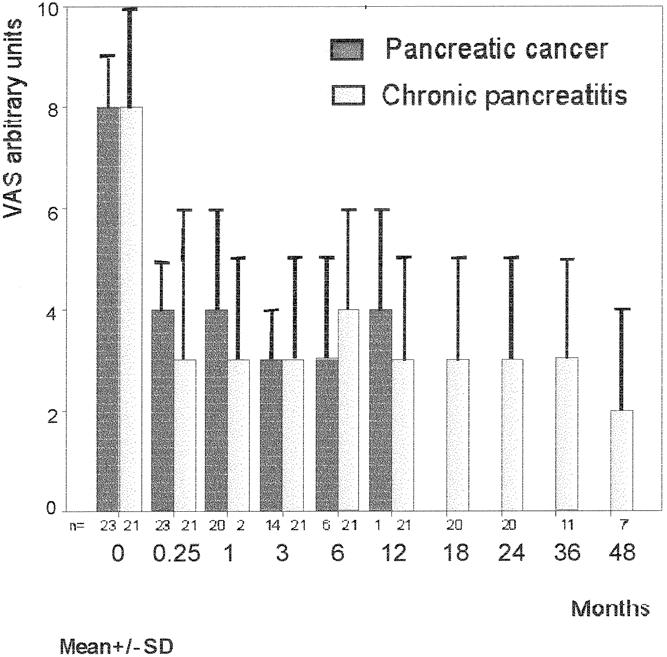

The average pain score was reduced by ≥50% in both patient groups (Fig. 1). The improvement was already obvious at the first evaluation—that is, 1 week after BTS, at which time 7 patients were pain-free and 17 patients scored ≤2 on the VAS. In fact, all patients reported lower scores—the average was 3, compared with 8 before BTS. Those who still felt pain after 1 week said the characteristics of the pain had changed. The pain-relieving effect was retained over time in both groups. Only four patients have returned to their preoperative VAS scores, two with pancreatic cancer and two with chronic pancreatitis. All seven patients with chronic pancreatitis under evaluation after 4 years indicated a continued decrease in their VAS scores, from a mean of 7 to 2.

Figure 1. Pain relief after bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy as evaluated by a visual analogue scale.

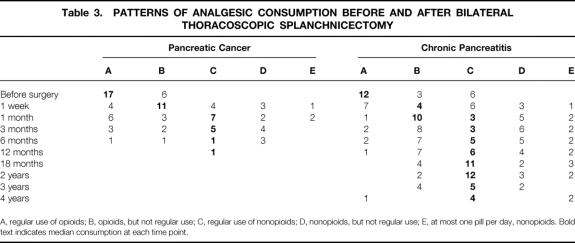

In both groups, the consumption of analgesics decreased (Table 3). After 1 month, >50% of the patients with pancreatic cancer were satisfied with nonopioids on a regular or irregular basis. The same was true for patients with chronic pancreatitis after 3 months and more.

Table 3. PATTERNS OF ANALGESIC CONSUMPTION BEFORE AND AFTER BILATERAL THORACOSCOPIC SPLANCHNICECTOMY

A, regular use of opioids; B, opioids, but not regular use; C, regular use of nonopioids; D, nonopioids, but not regular use; E, at most one pill per day, nonopioids. Bold text indicates median consumption at each time point.

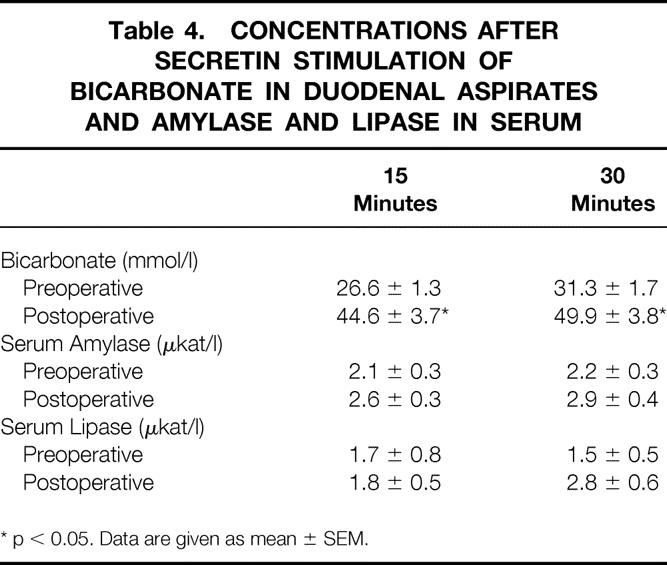

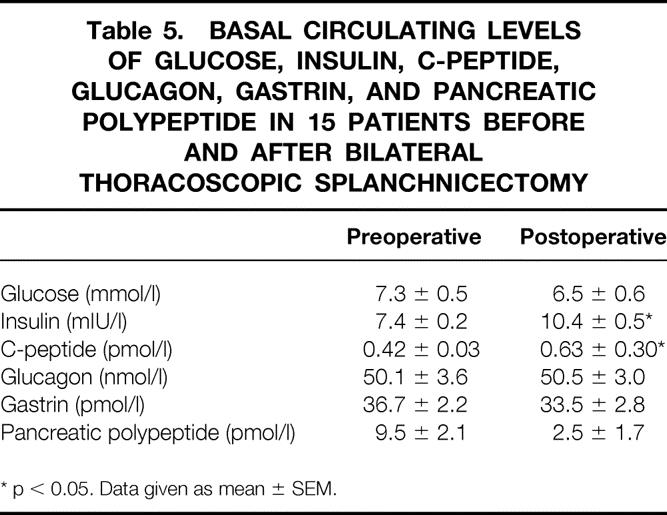

The secretin test showed a significantly increased secretory response of bicarbonate, whereas amylase and lipase concentrations were unaffected (Table 4). Basal plasma insulin and C-peptide values were also elevated. However, these changes were not reflected in any altered blood glucose levels (Table 5). Circulating basal glucagon, gastrin, and pancreatic polypeptide concentrations did not differ statistically.

Table 4. CONCENTRATIONS AFTER SECRETIN STIMULATION OF BICARBONATE IN DUODENAL ASPIRATES AND AMYLASE AND LIPASE IN SERUM

* p < 0.05. Data are given as mean ± SEM.

Table 5. BASAL CIRCULATING LEVELS OF GLUCOSE, INSULIN, C-PEPTIDE, GLUCAGON, GASTRIN, AND PANCREATIC POLYPEPTIDE IN 15 PATIENTS BEFORE AND AFTER BILATERAL THORACOSCOPIC SPLANCHNICECTOMY

* p < 0.05. Data given as mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

During the past two to three decades, an increasing number of treatment modalities have been used in the management of pancreatic pain. New pharmacologic and anesthesia approaches have been elaborated 16 and new surgical and radiotherapeutic techniques presented. 17–19 Most reports do not include either quantitative measures of pain assessment or serial evaluation of pain relief at regular intervals. Few series have provided randomized comparison of treatment results. Madsen and Hansen 20 reported a controlled randomized study comparing celiac plexus block and pancreaticogastrostomy for pain in chronic pancreatitis. In patients with pancreatic cancer pain, Lillemoe et al 9 used a similar study design in a comparison of intraoperative splanchnic block by 50% alcohol with placebo injections of saline. In a recent randomized study, 21 Polati et al evaluated the clinical benefit of neurolytic celiac plexus block compared with pharmacologic therapy. In these three controlled studies, chemical splanchnicectomy had significantly better pain-relieving effects than placebo, 8 whereas there was no difference between the other compared treatments, even if all four of them were beneficial. 20,21

Despite the reported progress, pancreatic pain remains a significant clinical problem. The recent promising results after chemical celiac block 8,9,20,21 and the refinement of the thoracoscopic technique have led to the introduction of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy in the treatment of pancreatic pain. 1 The present report is the largest prospective study, with longer follow-up than previous publications, on the pain-relieving effect of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy in pancreatic disease. 22–24 We used a bilateral approach, supported by the recent experience of Maher et al, 24 who found a need for repeat contralateral procedures 4 to 6 weeks after initial unilateral splanchnicectomy in half the patients.

Vagotomy has been advocated as an additional procedure to thoracic splanchnicectomy, because some pain fibers may run along this nerve. 25 Formerly, bilateral vagotomy was thought to reduce pancreatic pain. 26 However, because this benefit of vagotomy has not been properly demonstrated, and because delayed gastric emptying is reportedly common, 25,26 at present there are no grounds to include it.

Other authors have not mentioned the number of cut nerves or branches. We noted them in an attempt to find a possible relation to the degree of pain relief. We found a considerable variation in the number of identifiable nerves and branches. It is possible that at times the main greater and lesser splanchnic nerve trunks were sectioned and at other times their branches, which helps to explain the lack of correlation found between the number of cut nerves and the degree of pain relief.

In our series, the rate of bleeding complication was high (4/44 patients [9%]). In two cases, bleeding originated from arteries close to the transected nerves. These complications could have been avoided, perhaps, if each nerve had been clipped and divided instead of just being transected by diathermy, the technique we used in this series. However, we do not believe that the use of more ports would have reduced the risk of bleeding complications, because our two-port technique provided favorable working conditions. In addition, Maher et al, 24 using a four-port technique, reported that many of their 15 patients “complained of significant transient intercostal neuralgia.” We registered only one such complication in our 44 patients. Further, two of our bleeding complications emanated from a thoracic wall port. Thus, we believe that the number of ports should be minimized, considering that the surgery—at least in patients with cancer—is palliative, and a quick postoperative recovery is desirable. None of our patients had chylothorax, as has been reported by other authors. 24

This prospective study suggests that BTS may be useful in patients with pancreatic pain. VAS scores showed a mean pain relief of 50% throughout the whole study period (mean of 4 months for patients with pancreatic cancer and 43 months for those with chronic pancreatitis). The pain-relieving effects were recorded after the first postoperative week and were still present after 4 years in the seven patients with chronic pancreatitis under evaluation,. There was a marked average pain reduction in patients with cancer, although the pain pattern was not as clear because of malnourishment, nausea, and general malaise. Pain relief was accompanied by decreased consumption of analgesics.

Our results are in agreement with those of Cuschieri et al, 23 who found good short-term outcome in all their patients with pancreatic cancer and in 60% of those with chronic pancreatitis. Maher et al 24 reported significant improvement in pain, as measured by the VAS, after a median follow-up of 18 months. Of their 15 patients, all with chronic pancreatitis, 3 had no significant pain relief and were classified as having poor results.

In the patients evaluated before and after BTS, there were no signs of impaired pancreatic function that could be attributed to the procedure. Indeed, the results of the classic secretin test, showing pancreatic insufficiency before surgery, suggested improved exocrine secretion 2 weeks later. In addition, basal insulin and C-peptide levels were increased after BTS. These findings are in accordance with our previous studies of experimental selective microsurgical denervation of the rat pancreas, in which we found improvement after surgery in both exocrine 5 and endocrine 27 parameters, supporting the hypothesis that the sympathetic nervous system exerts inhibitory effects on the pancreas. 4,5 Basal hyperinsulinemia without hypoglycemia has been observed in studies of patients with pancreas transplants. The elevation of insulin is attributed to impaired insulin–insulin feedback inhibition mediated by the sympathetic system. 28,29 The results of the present clinical study indicate that BTS has no deleterious effect on either exocrine or endocrine pancreatic function.

In summary, we have shown a beneficial effect of BTS on pain in both pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Other smaller studies with shorter follow-up time support our findings. 1,23,24 The procedure is reasonably safe, and the hospital stay should be short. Further evaluation is warranted, but the procedure seems to be an option that should be considered in patients with pancreatic pain in whom drug therapy and surgical treatment have failed.

Discussion

PROF. C. RUSSELL (London, United Kingdom): Thank you very much indeed. I enjoyed listening to this study and I am indeed fascinated by the concept of splanchnicectomy. Mallet-Guy 40 years ago had done this procedure, and indeed François Dubois described transhiatal splanchnicectomy. One of the concerns that I have about this technique, which Mallet-Guy studied in patients over a period of 20 to 30 years and was relatively unconvinced by its long-term efficacy, is to determine what has changed with the new operation. I would like you firstly to comment on the long-term results of the procedure, particularly in chronic pancreatitis because this is not of concern in cancer.

Secondly, the actual way that the operation is performed seems to vary every time I hear the technique presented by enthusiastic thoracoscopists. I do not know why surgeons just do not divide the main greater splanchnic nerve. Actually, dividing the individual branches can be quite difficult, and on occasions they are difficult to see. In the paper, which I had the privilege of seeing, I think you did on one or two occasions actually divide the greater splanchnic nerve. I think you need to comment on what we are actually doing in this operation and what way is the best to standardize the procedure. I think that is important.

Thirdly, regarding the results of the various studies you have done on the biochemical and hormonal parameters, these are complex to interpret because you get different results whether you stimulate the alpha- or the beta-adrenergic receptors. The assessment is further affected by the way that the vagus nerve, which has both inhibitory and stimulatory effect on the celiac plexus, is damaged by the tumor or not. I wonder whether you would dissect those areas a little more for us.

DR. E. ZOUCAS (Lund, Sweden): I agree it is quite difficult at times to identify all the nerves arising from the thoracic ganglia. The easiest way is to start from the upper area, the sixth or the seventh ganglion, dissect there and work your way down. Obviously all surgeons have problems with identifying the nerve in the costophrenal margins, and maybe there is a rationale of going direct to the greater splanchnic nerve, but this is the problem. We have had difficulties when we tried to identify four nerves on either side in all cases. Sometimes we were lucky enough to identify five, but we have not been able to correlate the number of nerves to the effect. So it is a gray zone there; I cannot give you an exact answer.

Regarding the biochemical results, in the pancreas we have the vagus, as you said, and the sympathetic nerve fibers, but that’s not the whole truth. Today we know that we have nonadrenergic, noncholinergic nerves, and from a number of experimental data, it is my personal belief that they play a large role. We have been working with animal models and have been trying to affect the non-A, non-C, part of which, or rather a large part of which, use nitric oxide as a transmitter. And there is obviously an interaction between the sympathetic stimulus and the nitric oxide-mediating nerves. To what extent this affects pain I do not know, but it certainly affects function. The biochemical results seen here are only an indication that pancreas is insufficient, and no one claims that it is rendered sufficient by sympathectomy, but there is an indication that there is a regulatory role, the exact role to be identified in the future. Does that answer your questions?

PROF. O. GARDEN (Edinburgh, United Kingdom): Thank you for a clear presentation on a technique which appears to be a significant advantage in the management of pancreatic pain. I would like to follow on from the previous comments by asking for further details on one or two points of technique. The disadvantage of using an open thoracotomy technique was the fact that this approach swapped the patient’s abdominal pain for chest pain. You are unfortunate in this study in having a number of patients who have required to go on and undergo open thoracotomy for complications of bleeding. Was this part of the learning curve, and have you identified specific problems of technique which you would share with us? Have you eliminated these particular problems? In relation to this, it is clear from the experience of others who have been using this technique that there is considerable debate about whether there is a need to undertake bilateral splanchnicectomy. A number of workers have found that an approach on one side of the chest is sufficient, and again, I would just like you to comment on this issue.

Going on to longer-term management, I think that one of the more devastating consequences of a pancreatic malignancy is the progressive weight loss these patients have from their cancer cachexia. You indicated that you have not seen any deterioration in the physiological function of the pancreas, but I wondered if, in the cancer patients, you observed any effects on appetite, or indeed any stabilization or reversal of weight loss.

Finally, I would be grateful if you could give us a bit of guidance on the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Where does this particular technique fit in your overall armamentarium of surgical treatment for patients with chronic pancreatitis? When do you select this technique rather than an approach which involves a direct attack on the pancreas?

DR. ZOUCAS: First, the unilateral contra the bilateral technique. The results of the unilateral technique have been reported as transient, and I believe that transient results are more likely to occur when the nerves on one side are divided, leaving the other side to grow, and possibly to cover, the neurotomes of the other area which is already dissected.

The patients with bleeding complications certainly came in the beginning of the development of the operation technique. We have had four patients. Two of them had bleeding due to intercostal artery injury, and that can be avoided. You have to learn where to go into the intercostal space. Two patients had bleeding from an intercostal artery in the region of the splanchnic nerve, which was electrocoagulated. One of them was also undergoing a pulmonary biopsy, so it was a bit complicated as such. In the later stages we did not have any bleeding complications. There was only one patient with intercostal neuralgia. Increased numbers of such cases have been reported in the earlier literature. No cachectic patients did turn around to be anabolic. Maybe they could eat a bit better, but the nausea is there and the malaise due to the cancer is there, so I cannot see any difference.

PROF. L. FERNANDEZ-CRUZ (Barcelona, Spain): I enjoyed your presentation very much and I think it is a very interesting paper. I would like you to explain for us the criteria for selection of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Were there patients with left-sided chronic pancreatitis? Patients with big duct chronic pancreatitis? Patients with small duct chronic pancreatitis? This is the first question.

The second question is: Who made the interview with these patients? This is something very important in order to believe that patients answered in a proper manner to this very difficult question of pain.

The third question concerns the functional results. It is very striking that the insulin level and C-peptide levels were modified or altered after the operation, yet there were no changes in blood glucose. How do you explain this?

DR. ZOUCAS: Well, the patients with chronic pancreatitis were a quite large cohort of patients that had been followed up for several years. As I showed, they had at least 10 years of disease behind them. They had been treated with various other procedures, such as injection of alcohol in the semilunar ganglion and so on. As far as I know, only two patients in the group had dilated ducts. No other surgical procedures were done, and in our hands, surgical procedures for alleviation of pain in chronic pancreatitis are not so encouraging.

The interviews were made by one of the authors in a very systematic way, including all patients.

For the insulin—I have no explanation. The only thing I can say is that I believe that the sympathetic fibers are acting as a brake on the secretion of the beta cells, but today I am not able to explain why. As the values are in the normal range, probably the differences are too small for the body to respond to a decrease in blood glucose.

PROF. T. LERUT (Leuven, Belgium): In Belgium this is an operation not without learning curve, and not completely without complications. Perhaps I missed it, but I would like to have your comments on where this technique stands versus the nonsurgical methods such as alcohol infiltration, especially in the cancer patients. They, of course, have a very short life expectancy, and I think the nonsurgical methods can offer a very good perspective in terms of pain control. If so, would it not be interesting to randomize the surgical techniques versus the nonsurgical techniques such as alcohol infiltration?

DR. ZOUCAS (Closing Discussion): Alcohol infiltration has not been used so much in recent years in Lund. Obviously it has a role in pancreatic cancer patients with short life expectancy. Once the thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy has come over the learning curve, it is a quite easy method. What is striking is that immediately after the operation, these patients describe it as a different pain which is easier to suffer. Some of them even claimed not to have pain. That is striking. You do not often get that with infiltration of the celiac ganglion.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Ingemar Ihse, MD, PhD, FRCS, Dept. of Surgery, Lund University Hospital, S-221 85 Lund, Sweden.

Presented at the Sixth Annual Meeting of the European Surgical Association, at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, London, United Kingdom, April 23–24, 1999.

Accepted for publication July 1999.

References

- 1.Worsey J, Fersion PF, Keenan RJ, et al. Thoracoscopic pancreatic denervation for pain control in irresectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 1051–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holst JJ. Neural regulation of pancreatic exocrine function. In: Go VLW, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, et al, eds. The pancreas: biology, pathobiology, and disease. New York: Raven Press; 1993: 381–402.

- 3.Moreland HJ, Johnson LR. Effect of vagotomy on pancreatic secretion stimulated by endogenous and exogenous secretin. Gastroenterology 1971; 60: 425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer MV. Neurohormonal control of pancreatic enzyme secretion in animals. In: Go VLW, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, et al, eds. The pancreas: biology, pathobiology, and disease. New York: Raven Press; 1993: 425–448.

- 5.Nilsson C, Zoucas E, Sternby B, Ihse I. The effect of selective sympathetic denervation on pancreatic exocrine secretion. Res Exp Med 1997; 197: 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihse I, Andrén-Sandberg Å, Kobari M. Chronic pancreatitis: other procedures including pain relief operations. In: Carter D, Dussell DCG, Pitt HA, Bismuth H, eds. Rob & Smith’s operative surgery, hepatobiliary surgery. London: Chapman & Hall Medical; 1996: 566–569.

- 7.Mallet-Guy PA. Late and very late results of resection of the nervous system in the treatment of chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Am J Surg 1983; 145: 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengtsson M, Löfström JB. Nerve block in pancreatic pain. Acta Chir Scand 1990; 156: 285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Kaufman HS, et al. Chemical splanchnicectomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective randomised trial. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen H, Myren J. Secretin dose-response in health and chronic pancreatic inflammatory disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1975; 10: 851–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torell JJ, Larsson SM. Radioimmunoassays and related techniques. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co; 1978:205–211.

- 12.Polonsky KS, Rubinstein AH. Secretin and metabolism of insulin, pro-insulin and c-peptide. In: de Groot LT, ed. Endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989: 1304–1317.

- 13.von Schenck H, Nilsson OR. Radioimmunoassays of extraction of glucagon compared with three non-extractional assays. Clin Chem Acta 1981; 109: 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuigan JE. Hormones of the gastrointestinal tract. In: De Grott LJ, ed. Endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989: 2742–2747.

- 15.Chance RE, Moon NE, Johnson MC. Human pancreatic polypeptide (HPP) and bovine pancreatic polypeptide (BPP). In: Jaffe BM, Behlman HR, eds. Methods of hormone radioimmunoassay. New York: Academic Press; 1979: 657–672.

- 16.Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. Pain management in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 1996; 78: 639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beger HG, Büchler M, Bittner R, et al. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in severe chronic pancreatitis. Early and late results. Ann Surg 1989; 209: 273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey CF, Schmith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 1987; 2: 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittington R, Dobelbower RR, Mohiuddin M, et al. Radiotherapy of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a six-year experience with 104 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1981; 7: 1639–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madsen P, Hansen E. Celiac plexus block versus pancreaticogastrostomy for pain in chronic pancreatitis. A controlled randomised study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1985; 20: 1217–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polati E, Finco G, Gottin L, et al. Prospective randomised double-blind trial of neurolytic celiac plexus block in patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chien-Chih L, Lein-Ray MD, Yie-Wen L, Man-Pun Y. Bilateral thoracoscopic lower sympathetic-splanchnicectomy for upper abdominal cancer pain. Eur J Surg 1994; 572: 59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuschieri A, Shimi SM, Crosthwaite G, Joypant V. Bilateral endoscopic splanchnicectomy through a thoracoscopic approach. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1994; 39: 44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maher JW, Johlin FC, Pearson D. Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy for chronic pancreatitis pain. Surgery 1996; 120: 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone HH, Chwain EJ. Pancreatic denervation for pain relief in chronic alcohol associated pancreatitis. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone HH, Mullins RJ, Scovill WA. Vagotomy plus Billroth II gastrectomy for the prevention of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Ann Surg 1985; 201: 684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nilsson C, Zoucas E, Lundquist I, Ihse I. The effect of selective pancreatic denervation on pancreatic endocrine function. (In press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Boden G, Chen X, DeSantis R, et al. Evidence that suppression of insulin secretion by itself is neurally mediated. Metabolism 1993; 42: 786–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luzi l, Battezzatti A, Perseghin G. Lack of feedback inhibition of insulin secretion in denervated human pancreas. Diabetes 1992; 41: 1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]