Abstract

Objective

To study factors influencing complications and death after operations for small bowel obstruction (SBO) using multifactorial statistical methods.

Summary Background Data

Death after surgery for SBO is believed to be influenced by factors such as old age, comorbidities, bowel gangrene, and delay in treatment. No studies have been reported in which adverse factors related to death and complications have been systematically investigated with modern statistical methods.

Methods

The authors studied retrospectively 877 patients who underwent 1,007 operations for SBO from 1961 to 1995. Patients with paralytic ileus, intussusception, and abdominal cancer were excluded. Odds ratios for death, complications, postoperative hospital stay, and strangulation were calculated by means of logistic regression analyses.

Results

Death and complication rates decreased during the study period. Old age, comorbidity, nonviable strangulation, and a treatment delay of more than 24 hours were significantly associated with an increased death rate. The rate of nonviable strangulation increased markedly with patient age. Major factors increasing the complication rate were old age, comorbidity, a treatment delay of more than 24 hours, and the need for repeat surgery.

Conclusion

Death and complication rates after SBO decreased from 1961 to 1995. Major factors influencing the rates were age, comorbidity, nonviable strangulation, and treatment delay. Nonviable strangulation was more common in old patients.

There is limited information on the factors causing death and complications after surgery for bowel obstruction. Studies have shown that death is influenced by patient-related factors such as age, comorbidity, bowel gangrene, and delay in treatment. 1–8 However, a major problem with all these studies is that interrelated variables may be a confounding factor in studies of the cause-and-effect type—for instance, old age increases the death rate. Comorbidity (e.g., cardiovascular or pulmonary disease) also contributes to the increased death rate after surgery. However, comorbidity occurs more commonly in old patients. Interrelations between individual factors can be studied only by multifactorial statistical methods, which have not been used in any of the previously published studies focusing on death and complications after surgery for small bowel obstruction (SBO).

The purpose of this study was to investigate complications and death after surgery for SBO during a 35-year period in a large institutional retrospective patient series. Multifactorial statistical methods were used to determine individual factors influencing major outcome variables. We also sought time trends from 1960 to 1995.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We retrospectively studied 877 patients who underwent 1,007 operations for mechanical SBO at Haukeland University Hospital from 1961 to 1995. The hospital had a relatively stable catchment area during this time period. All patients admitted every other year in this period were investigated (5 years per decade, 2 years in the period 1990–95). Each operation was entered as a separate “case” in the study, although 107 patients underwent surgery more than once (130 second or later operations). Only when calculating the frequency of previous operations were patients, not cases, counted. The diagnosis of mechanical SBO was confirmed at surgery. In a few situations in which operative notes were missing, operation codes (national coding system) and diagnostic codes (ICD-based) were used to establish the diagnosis of SBO. Patients with large bowel obstruction and paralytic ileus, intussusception, and abdominal cancer (primary and secondary) were excluded.

Before 1972, a manual recording system was used to identify patients who underwent surgery; after this, a computerized system was used. The following information was retrieved: patient demographics; previous abdominal surgery; comorbidity; time of onset of symptoms, admission, and surgery; preoperative radiologic investigations; number of operations for SBO; cause of obstruction; presence of strangulated bowel (viable or nonviable); type of operation; length of postoperative hospital stay; number and type of complications; and death.

In this study, “hospital death” means death before discharge. Patients dying were also included in the complication group; most had a well-defined complication, but some died as a direct result of the SBO (mainly as a result of massive bowel gangrene).

Separate analyses were performed for the total patient group and for the two major subgroups (SBO caused by adhesions and by hernias). Chi-square tests were used to compare different groups (e.g., with or without premorbid illness; with viable, nonviable, or no strangulation). Odds ratios for death, complications, postoperative hospital stay, and nonviable strangulation were calculated in a logistic regression analysis. In these analyses, age, sex, and other relevant factors expected to have an influence on the independent variables were included.

RESULTS

Of 1,007 operations for mechanical SBO, 877 were first operations for SBO and 130 were second, third, or up to seventh (one patient only) procedures for SBO. The cause of obstruction is shown in Table 1. Adhesions accounted for 526 operations (54%). Obstructions caused by adhesions increased in this time period. In some patients, the cause of obstruction was considered to be a combination of adhesions and another factor (e.g., Crohn disease or foreign body). Such patients were categorized as having, for instance, Crohn disease or foreign body, not as having adhesions. The second most common cause of obstruction was incarceration of bowel in hernias, dominated by inguinal and femoral hernias. The percentage of obstructions caused by hernias decreased from 41% in the 1960s to 26% in the 1990s. The incidence of SBO caused by radiation injury and Crohn disease tended to increase with time, but the numbers were small.

Table 1. CAUSES OF OBSTRUCTION RELATED TO YEAR OF ADMISSION

* Meckel diverticulum, diverticular disease, others.

† Definite cause of obstruction not established for 32 cases, which were excluded from analyses.

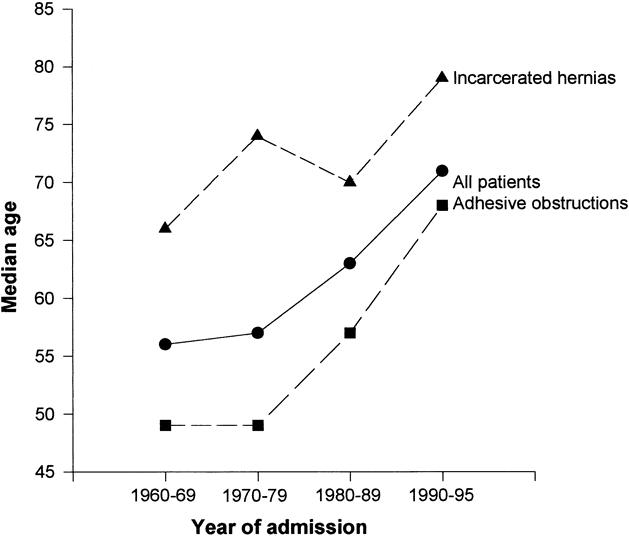

Figure 1 shows the median age by time period of admission for all patients. The median age increased during the study period for all patients and in the two subgroups. Women represented 39% of the whole study group, 44% of those with adhesive obstructions, and 32% of those with incarcerated hernias. The proportion of women increased from 29% in the 1960s to 43% in the 1970s, and then stabilized around 42%.

Figure 1. Median age by year of admission, overall and in two subgroups of patients: all patients, n = 1007; adhesive obstructions, n = 526; incarcerated hernias, n = 293.

Thirty-eight percent of the patients (335/877) had undergone no previous abdominal operation before their first operation for SBO, 44% (386/877) had undergone one previous abdominal operation, and 18% had undergone two or more previous abdominal operations. In patients with adhesive obstructions, 85% had undergone at least one previous laparotomy, as opposed to 30% of patients with incarcerated hernias. In the 386 patients who had undergone only one previous abdominal operation, 101 (26%) were gynecologic operations, 96 (25%) appendectomies, 53 (14%) operations on the stomach, 55 (14%) operations on the small or large bowel, and 81 (21%) others (including operations on the urinary and vascular systems, the liver, spleen, gallbladder, and pancreas).

Comorbidity is shown in Table 2. An associated premorbid illness was present in 30% of patients, with cardiovascular disease dominating (14%). Premorbid illness was related to patient age; in patients 50 years or younger, the frequency of comorbidity was 11%. This figure increased to 36% in patients 50 to 75 years and to 52% in those older than 75 years (P < .001).

Table 2. COMORBIDITY IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING SURGERY FOR SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Many patients had more than one disease and are thus registered in two disease groups.

Information on comorbidity was not available for all patients. The numbers therefore differ somewhat from those given in Table 1.

* Percentage of all cases in each group in which premorbid illness was registered.

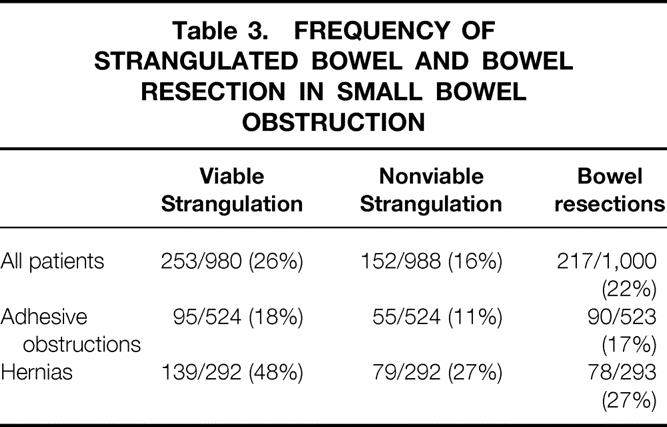

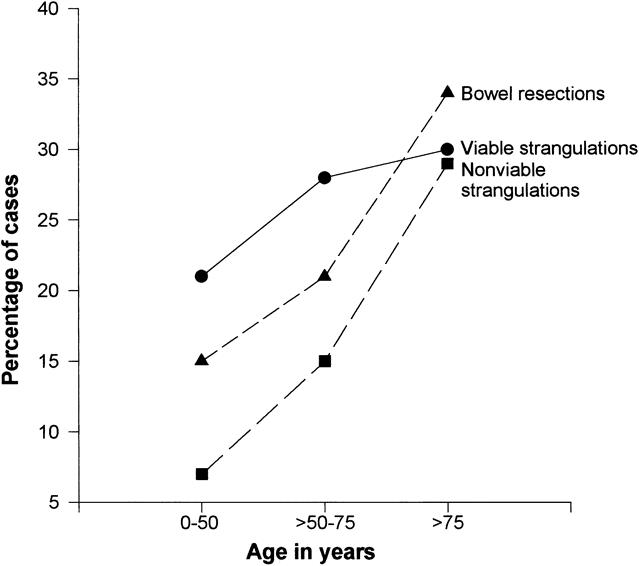

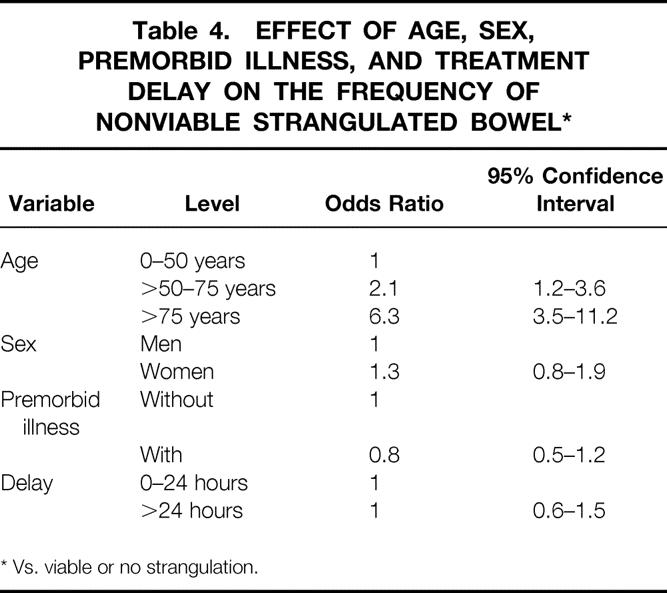

Table 3 shows the frequency of strangulated bowel and bowel resections. In 26% of all cases, a viable strangulated bowel loop was found; nonviable strangulation occurred in 16%. Bowel resection was carried out in 152 patients with nonviable strangulation and also in 65 patients with massive adhesions or perforation (accidental or caused by the obstruction). The proportion with strangulation was smaller in those with adhesive obstructions than in those with incarcerated hernias. Figure 2 shows strangulation and resection rates related to patient age. The rate of viable and nonviable strangulation and bowel resection increased significantly with increasing patient age (P < .001 for all three variables). However, because patient age is related to premorbid illness, a logistic regression analysis was undertaken to determine the individual effect of each variable (Table 4). This shows that only age had a significant effect on the rate of nonviable strangulation, with patients older than 74 years of age having a sixfold increase in the risk of nonviable strangulation compared with those younger than 50. Sex, premorbid illness, and in particular treatment delay did not influence the rate of nonviable strangulation.

Table 3. FREQUENCY OF STRANGULATED BOWEL AND BOWEL RESECTION IN SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Figure 2. Strangulation and bowel resection in three age groups: viable strangulation, n = 253; nonviable strangulation, n = 152; bowel resections, n = 216.

Table 4. EFFECT OF AGE, SEX, PREMORBID ILLNESS, AND TREATMENT DELAY ON THE FREQUENCY OF NONVIABLE STRANGULATED BOWEL*

* Vs. viable or no strangulation.

<./>

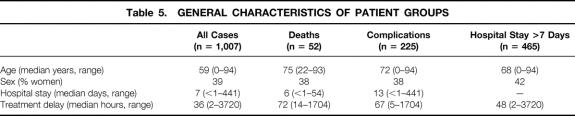

Characteristics of the patients who had complications, who died, or who had a prolonged postoperative hospital stay are shown in Table 5. Age and treatment delay were significantly higher among patients who died. The median postoperative hospital stay was relatively low in the patients dying, demonstrating that death occurred soon after the operation for SBO. Patients with complications spent more time in the hospital.

Table 5. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENT GROUPS

Fifty-two patients died (5%). The causes of death were massive bowel infarction (n = 15), pulmonary disease (n = 11), heart disease (n = 8), thrombosis/embolism (n = 3), postoperative peritonitis (n = 3), renal failure (n = 1), stroke (n = 1), and others (cause of death unknown in 2 patients).

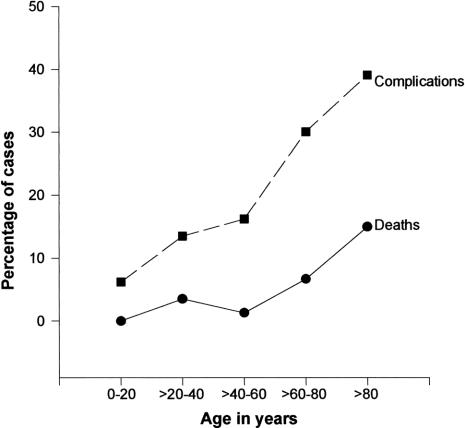

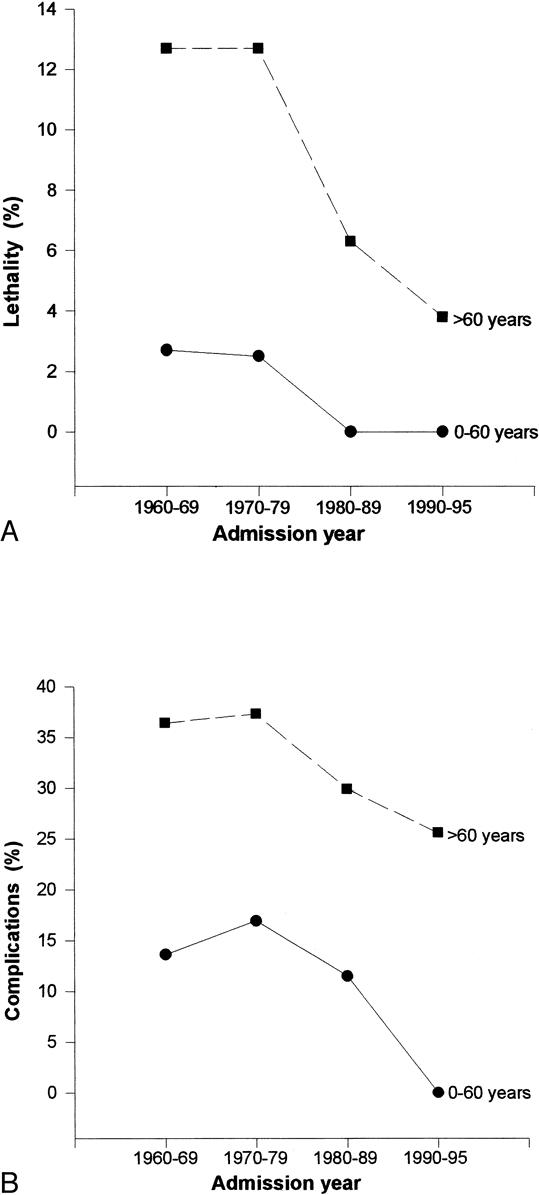

Death and complication rates by year of admission in two age groups are shown in Figure 3. There was a substantial reduction in the death rate since the 1970s. Few deaths occurred in patients 0 to 60 years of age (four patients in the 1960s [2.7%] and four in the 1970s [2.5%]). Most deaths occurred in patients older than 60 years, but the death rate decreased significantly with time in these patients (P = .04, chi-square test). Similarly, the complication rate was higher among patients older than 60 years and decreased for both age groups during the study period. Figure 4 shows death and complication rates by age. A marked increase in death and complications is seen for patients older than 60 years.

Figure 3. (A) Death by year of admission in two age groups: age 0 to 60 years, n = 508; age older than 60 years, n = 490. (B) Postoperative complications by year of admission in two age groups: age 0 to 60 years, n = 505; age older than 60 years, n = 488.

Figure 4. Death and complication rates by patient age: deaths, n = 52; complications, n = 225.

Figure 5 shows the influence of premorbid illness on the rates of death and postoperative complications. The death rate was much higher among patients with premorbid illness than in healthy ones. There was, however, an increase in the death rate with increasing age in both patient groups. The risk of death after surgery for SBO in healthy patients younger than 50 years is almost zero, but premorbid illness increases markedly the complication rate in these patients.

Figure 5. (A) Deaths by age according to premorbid illness: with premorbid illness, n = 270; without premorbid illness, n = 615. (B) Complications by age according to premorbid illness: with premorbid illness, n = 269; without premorbid illness, n = 613.

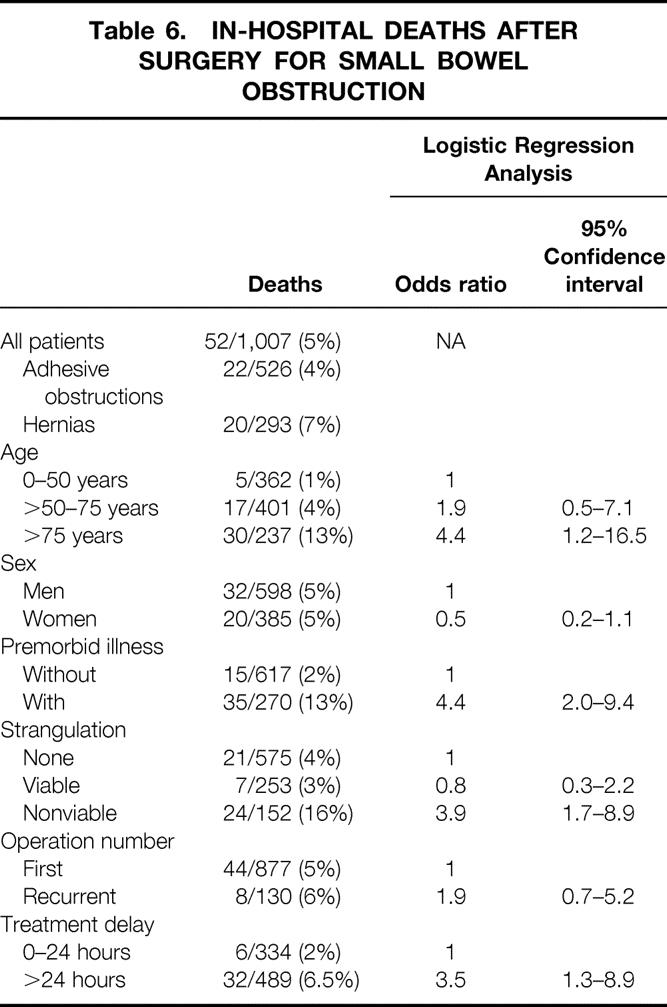

The effect of individual factors on the death rate is shown in Table 6. Patient age, premorbid illness, and nonviable strangulation significantly influenced the death rate (odds ratio ∼4 for each of these factors). A treatment delay of more than 24 hours was also significantly associated with an increased risk of death. Year of admittance and the number of previous abdominal operations (none vs. one or more) did not influence the risk of death.

Table 6. IN-HOSPITAL DEATHS AFTER SURGERY FOR SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

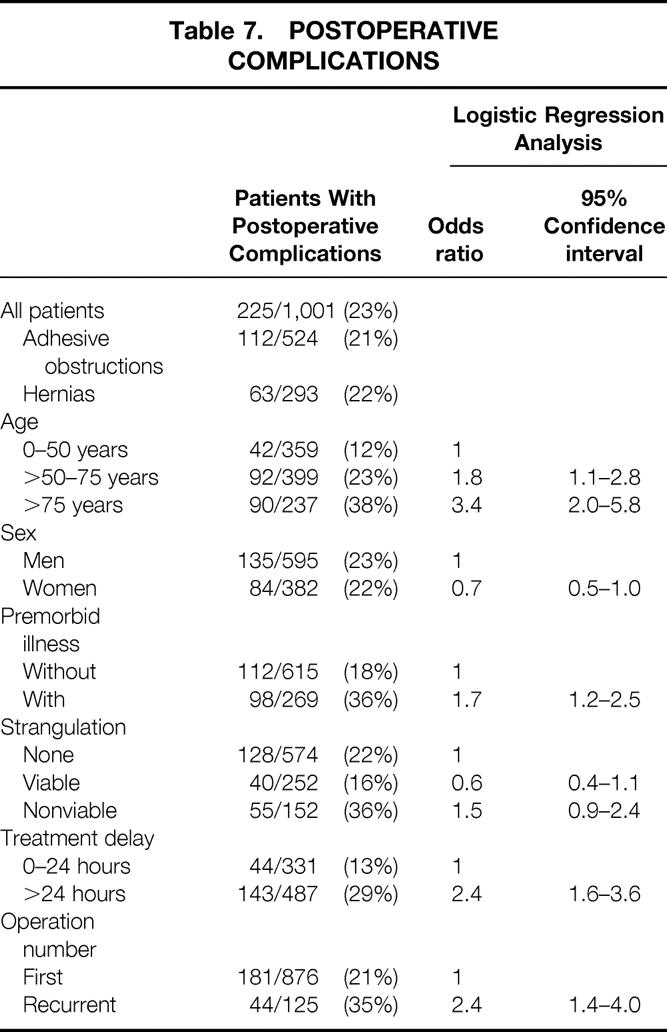

Table 7 shows the frequency of and factors influencing postoperative complications. In 23% of the cases, the patient had one or more complications (pulmonary, cardiac, urinary, or neurologic complications; thrombosis/embolism; major hemorrhage; wound infection or rupture; abdominal abscess; fistulas; and septicemia). The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that odds for complications increased significantly with age, the presence of premorbid illness, and a treatment delay of more than 24 hours. It was also higher after recurrent operations versus the first operation for SBO. The presence of strangulation had no significant effect on the complication rate.

Table 7. POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

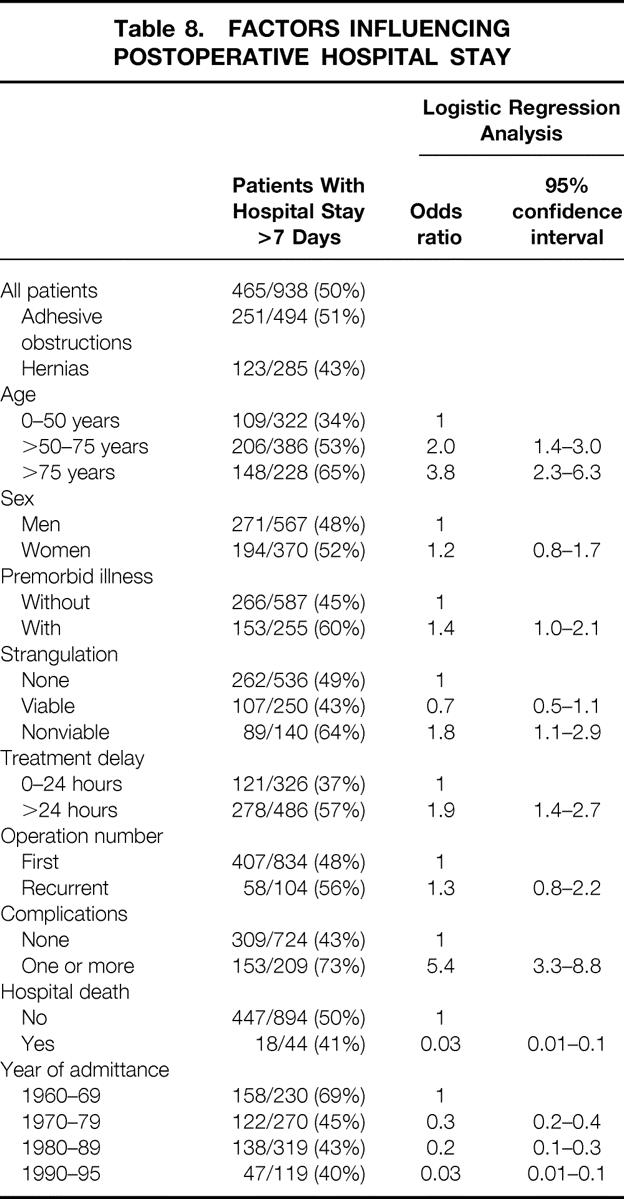

The median hospital stay was 7 days for the whole patient group, 7 days for the hernia group, and 8 days for the adhesive obstruction group. Table 8 demonstrates the odd ratios for having a postoperative stay of more than 7 days. Old age, nonviable strangulation, and a treatment delay of more than 24 hours were significantly associated with a long stay. The length of stay decreased over the period studied. Patients dying in the hospital had a significantly shorter postoperative stay.

Table 8. FACTORS INFLUENCING POSTOPERATIVE HOSPITAL STAY

DISCUSSION

The causes of obstruction reported here correspond well with those found in earlier studies, 1,9–11 despite the fact that obstructions caused by malignant diseases were excluded from our study. Adhesions accounted for 54% of the obstructions, incarcerated hernias 30%. The percentage of hernias dropped and the percentage of adhesive obstructions rose during the past three decades (see Table 1).

Age appears to be the major factor increasing death and complication rates. The median age of patients undergoing surgery for SBO increased from 56 years in the 1960s to 71 in the 1990s. Even so, the death and complication rates decreased.

The incidence of associated illness was 30% in this study. In a 1966 study by Lo et al, 2 the incidence was 55%, although obstructions caused by tumors were included in that study. As expected, we found a significant correlation between age and associated illness: 52% of patients older than 75 years had associated illness compared with 36% of those 50 to 75 years old and 11% of those 50 or younger (P < .001). Therefore, it is important to separate the effects of age and premorbid illness on death and complication rates when comparing studies on complications after SBO. Old age, irrespective of associated disease, is a significant risk factor.

The incidence of nonviable strangulation was 16%. Interestingly, age was the only factor that significantly influenced the rate of strangulation. Bizer et al 12 demonstrated a similar association between bowel strangulation and age older than 70 years. They found no correlation between duration of symptoms before admission and the incidence of strangulation, nor did the time from admission to surgery correlate with the incidence of strangulation. This corresponds well with our finding that delayed surgical treatment had no significant effect on the rate of nonviable strangulation. Similarly, Tanphiphat et al 13 in 1987 found that patients who underwent surgery more than 48 hours after admission had a significantly lower incidence of nonviable and borderline bowel viability than those who underwent surgery within 12 hours of admission. In an older study, 2 a delay in treatment was shown to increase the rate of bowel resection. The reason why we found no such correlation must be that patients with strangulation have more severe symptoms (even if this cannot easily be shown), leading to early admission and surgery.

The overall death rate in the present study was 5%. The death rate from SBO has decreased from approximately 60% in 1908 14 to approximately 20% in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s and 13% in 1955. 3 Death rates of 4%15 to 28%16 have been reported for the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In the present study, the death rate decreased markedly during the study period of 35 years (see Fig. 3), especially for patients aged 60 years or older.

The distribution of cases in a study population is, of course, essential when death rates are considered. In some studies, the death rate is given for both those who do and do not undergo surgery combined, resulting in rates of 1% to 7%. 12,13,15 Greene 16 included only patients 65 years or older, which would produce a higher death rate. The inclusion of large bowel obstructions and obstructions caused by cancer also produces higher death rates (14–28%) 4,16,17 than in studies where these groups were excluded, such as the present study.

A major purpose of this study was to elucidate individual factors influencing the complication and death rates by eliminating the confounding effect of interrelated variables. Using logistic regression analysis, we found that old age, comorbidity, nonviable strangulation, and a treatment delay of more than 24 hours all increased the death rate. Age older than 75 years and comorbidity increased the risk of death four to five times compared with younger and healthy patients. Whether the operation was a primary or recurrent operation did not significantly affect the death rate. The fact that the complication rate was influenced by a repeat operation makes it probable that it also may affect the death rate, even if this could not be shown in this study.

Only a few studies have systematically investigated factors that increase the rates of death and complications, calculating the relative effect of each separate factor. Nevertheless, many of the results reported previously agree with ours. In 1955 Smith, 3 in a study of 1,252 instances of intestinal obstruction, found that bowel gangrene, perforation, severe prolonged intestinal distention, and the extremes of age reduced the survival rate. Ti and Yong 4 found that extremes of age, comorbidity, bowel gangrene, large bowel obstruction, and malignancy increased the death rate. The adverse effect of bowel strangulation on survival has been known for many years. We found a death rate of 16% in patients with nonviable strangulation, compared with 4% in patients without strangulation. Deutsch et al 5 found a significant relation between strangulation and death: the death rate was 13% in the nonstrangulated group versus 29% in the strangulated group. Similar results were obtained in a study by Shatila et al, 6 and the relation between old age and death has been reported in several studies. 2–4 Deutsch et al 5 found a statistically significant correlation between age and death as well as between bowel strangulation and death.

The adverse effect of delayed treatment was discussed in a 1970 article by Playforth et al. 1 They found an increase in complication and death rates with an increased interval between the onset of symptoms and admission and between admission and surgery, as well as higher death and complication rates in patients who underwent bowel resection. However, no statistical analysis was presented. In a 1978 study by Ulvik et al 7 of 103 patients with adhesive SBO, the risk of death was doubled in patients with a duration of symptoms of more than 24 hours. No statistics was given and the study population was small, but the results were much the same as those of our study. We found a threefold increase in the risk of death with a treatment delay of more than 24 hours.

The overall complication rate in this study was 23%, with almost no difference between the two major subgroups. Asbun et al 15 found a complication rate of 21% overall but 31% in patients who underwent surgery. Their study included patients with cancer, which could account for their high rate of complications. Davis and Sperling 18 reported a complication rate of 19.8%, but 15% of the patients did not undergo surgery. The most common complications in that study were wound infections and peritonitis. In our study, the major complications were cardiovascular and pulmonary ones; this may be due to old age followed by a high frequency of comorbidity.

Old age, premorbid illness, treatment delay, and recurrent operations were all each associated with high complication rates. For patients older than 75 years, the odds of experiencing postoperative complications were 3.4 that of patients 0 to 50 years. Other factors influencing the rate of complications were treatment delay of more than 24 hours and recurrent operation; both these factors more than doubled the risk of complications. A relation between delayed surgical treatment and increased complication rates has been shown in other studies. 9,19 Comorbidity also increased the risk of postoperative complications, although this factor had less effect on the complication rate than on the death rate. The reason for this must be that many patients (especially old patients) have complications, but those who are already ill and weak are more likely to die of their complications. Playforth et al 1 found a connection between increased complication frequency and delayed treatment. They also found a higher complication rate among patients who underwent bowel resection.

The median length of stay for all patients was 7 days (see Table 5). The average stay found by Tanphiphat et al 13 was 13 days among patients who underwent surgery; however, they included the preoperative stay as well. A complication is an important factor contributing to a long stay. 19 In our study, the median postoperative stay was 13 days for patients with complications. Patients who died had a short hospital stay (5.5 days), obviously as a result of severe complications occurring soon after surgery (see Table 8). Complications, old age, and an early year of admission were the most important factors contributing to a prolonged hospital stay. The regression analysis disclosed a marked effect of the year of admission, showing a trend in health care policy toward shorter stays. Other factors significantly affecting the postoperative stay were a treatment delay of more than 24 hours and nonviable strangulated bowel. Hofstetter 9 showed that a delay of more than 24 hours (delay from admission to surgery) increased the hospital stay by 1 week.

In conclusion, we found that rates of death and complications and the length of stay decreased significantly from 1961 to 1995. Old age, comorbidity, nonviable strangulation, and a treatment delay exceeding 24 hours were significantly associated with an increased death rate. The rate of nonviable strangulation was significantly increased in older patients. Major factors increasing complication rate were old age, comorbidity, a treatment delay of more than 24 hours, and recurrent operations. A postoperative stay of more than 7 days was significantly correlated with complications, old age, nonviable strangulation, and a treatment delay of more than 24 hours.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Knut Svanes, MD, PhD, Dept. of Surgery, Haukeland Hospital, 5021 Bergen, Norway.

Supported by grants from The Research Council of Norway.

Accepted for publication June 28, 1999.

References

- 1.Playforth RH, Holloway JB, Griffen WO. Mechanical small bowel obstruction: a plea for earlier surgical intervention. Ann Surg 1970; 171:783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo AM, Evans WE, Carey LC. Review of small bowel obstruction at Milwaukee County General Hospital. Am J Surg 1966; 111:884–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith GA. Mechanical intestinal obstruction: a study of 1252 cases. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1955; 100:651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ti TK, Yong NK. The pattern of intestinal obstruction in Malaysia. Br J Surg 1976; 63:963–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutsch AA, Eviatar E, Gutman H, Reiss R. Small bowel obstruction: a review of 264 cases and suggestions for management. Postgrad Med J 1989; 65:463–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shatila AH, Chamberlain BE, Webb WR. Current status of diagnosis and management of strangulation obstruction of the small bowel. Am J Surg 1976; 132:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulvik NM, Qvigstad E. Mechanical small bowel obstruction due to adhesions. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1978; 67 (1):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mucha P Jr. Small intestinal obstruction. Surg Clin North Am 1987; 67:597–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofstetter SR. Acute adhesive obstruction of the small intestine. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1981; 152:141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewardson RH, Bombeck CT, Nyhus LM. Critical operative management of small bowel obstruction. Ann Surg 1978; 187:189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEntee G, Pender D, Mulvin D, et al. Current spectrum of intestinal obstruction. Br J Surg 1987; 74:976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bizer LS, Liebling RW, Delany HM, Gliedman ML. Small bowel obstruction. Surgery 1981; 89:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanphiphat C, Chittmittrapap S, Prasopsunti K. Adhesive small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg 1987; 154:283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scudder CL. Principles underlying treatment of acute intestinal obstruction. Trans NH Med Soc 1908:234. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asbun HJ, Pempinello C, Halasz NA. Small bowel obstruction and its management. Int Surg 1989; 74:23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene WW. Bowel obstruction in the aged patient. Am J Surg 1969; 118:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sufian S, Matsumoto T. Intestinal obstruction. Am J Surg 1975; 130:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis SE, Sperling L. Obstruction of the small intestine. Arch Surg 1969; 99:424–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bender JS, Busuito MJ, Graham C, Allaben RD. Small bowel obstruction in the elderly. Am Surg 1989; 55:385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]