Abstract

Objective

To assess the surgical risk of additional mitral valve repairs in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Summary Background Data

Severe mitral regurgitation in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy increases the death rate and symptomatic status. The 1-year survival rate for medical therapy in this subset of patients is less than 20%. Transplantation is usually not feasible because of donor shortage and death while on the waiting list.

Methods

To assess additive risk, a retrospective chart review from 1993 to 1998 was performed comparing patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ejection fraction [EF] <25%) and severe mitral regurgitation undergoing mitral valve repair and coronary artery bypass graft operations with patients with an EF of <25% undergoing coronary artery bypass graft alone. These groups were also compared with 140 patients receiving heart transplants since 1993 (group 3).

Results

The overall hospital death rate for group 1 was 6.3%. The one death occurred 2 weeks after surgery secondary to sepsis. This was not significantly different from the death rate of 4.1% in group 2. In group 1, there were two deaths at 1 year (87% survival rate), one related to heart failure. One patient was New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV at 1 year; the remainder of patients were NYHA class I–II. These results were not significantly different than the 8% death rate noted with transplantation. There was no change in EF and minimal residual mitral regurgitation in group 1 based on postoperative transesophageal echocardiography, whereas group 2 had an average 11.7% improvement in EF.

Conclusions

Previously, severe mitral regurgitation in the setting of ischemic cardiomyopathy has been associated with poor survival. In these authors’ experience, repairing the mitral valve along with coronary artery bypass grafting does not increase the surgical risk, yields improvement in symptomatic status, and compares favorably to coronary artery bypass grafting alone and cardiac transplantation. However, the lack of change in EF in these patients probably represents an overestimation of the EF before surgery secondary to severe mitral regurgitation.

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is often a complication of end-stage cardiomyopathy. It can result from dilation of the mitral annular-ventricular apparatus with altered ventricular geometry and ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction. 1,2 This process leads to a cycle of more volume overload, which can lead to progressive annular dilation, worsened MR, and more severe symptoms of congestive heart failure. 3

Severe MR in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy is a difficult management entity. Not only do these patients have worsened symptoms, but they also have an increased death rate. The reported 1-year survival rate for medical therapy in this subset of patients is less than 20%. 4 Although transplantation is a viable option for this group of patients, donor shortage remains a serious issue.

Recent studies have shown that mitral valve repair in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy is not only feasible but also improves ventricular function and overall survival. 4–7 Most of these studies, however, have dealt with mitral valve repairs in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Patients with severe MR secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy have two separate pathophysiologies that not only augment pump failure, but also need to be each dealt with separately surgically. To explore this issue in further detail, we retrospectively assessed the surgical risk of additional mitral valve repairs in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and severe MR undergoing concomitant coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).

METHODS

A retrospective chart review was performed at the University of Virginia from 1993 to 1998. A total of 16 consecutive patients with severe MR (3–4+) and chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy underwent mitral valve repair with concomitant CABG. MR was assessed by color-flow Doppler ultrasonography and cardiac catheterization and interpreted by a cardiologist. Severity of MR was graded as mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe. Ischemic cardiomyopathy was defined as severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction (EF) of less than 30%, also based on ultrasonography and cardiac catheterization, with coexisting significant coronary artery disease. Patients were excluded from the study if they had evidence of primary valvular disease or required emergency surgery for acute coronary occlusion. Acute myocardial revascularization in cases of acute occlusion could result in markedly improved ventricular function and thus not be truly representative of patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. 8 Patients revascularized after thrombolytic therapy were excluded for similar reasons. 9 Patients diagnosed with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy were not included in this study. Exclusion criteria from being revascularized were the same for all patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy undergoing CABG. Patients were not considered candidates for revascularization if they lacked graftable coronary arteries. In addition, patients had to have evidence of viable ischemic myocardium that would have been amenable to a revascularization procedure. To assess this potential for myocardial functional improvement after surgery, all patients at our institution undergo a preoperative thallium scintigraphy perfusion scan. There was no minimal level of left ventricular function required in terms of EF unless, however, patients had severely decreased left ventricular function to the point where a ventricular assist device was likely to be required. These patients were excluded and referred for cardiac transplantation.

Death rates, patient demographics, and preoperative and postoperative EFs were obtained from a second group of patients (group 2) with ischemic cardiomyopathy undergoing CABG alone (these patients, however, did not have significant MR). We also performed a retrospective medical record review of 121 consecutive patients with a left ventricular EF of less than 30% who underwent isolated CABG at the University of Virginia between 1994 and 1997.

The University of Virginia cardiac transplant registry was used to obtain 30-day and 1-year survival rates for 140 patients undergoing cardiac transplantation from 1993 through 1998.

Data Collection and Follow-Up

All preoperative, surgical, and postoperative data were obtained from hospital and clinical charts, anesthesia records, surgical reports, and perfusion records. Long-term follow-up was obtained from outpatient medical records. Telephone interviews of the patients themselves confirmed their symptomatic status.

Statistical Analysis

Ejection fraction, age, and number of CABGs between groups were compared using the Student t test, with a critical value of .05. All other patient parameters were compared using the Fisher exact analysis, with a critical value of .05.

Surgical Technique

All procedures were performed through a median sternotomy. The left internal mammary artery was harvested in 15/16 (94%) patients, followed by systemic heparinization. Bicaval venous cannulas and an ascending aortic cannula were used for cardiopulmonary bypass. All coronary anastomoses using the left internal mammary artery or saphenous vein grafts were performed in the standard fashion. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography was routinely used to evaluate the specific anatomy of the MR. The mitral valve was exposed through an incision anterior and parallel to the entrance of the right pulmonary veins, followed by development of the Waterston groove. Repair of the mitral valve included some form of annuloplasty involving a flexible or a rigid annuloplasty ring. In cases that involved a prolapse of the middle portion of the anterior leaflet, the “edge-to-edge” technique, as previously described, 10 was used, creating a double mitral orifice. Intraoperative valve function was assessed by forceful injection of cold saline into the left ventricle before atrial closure and by transesophageal echocardiography after cardiopulmonary bypass was terminated.

RESULTS

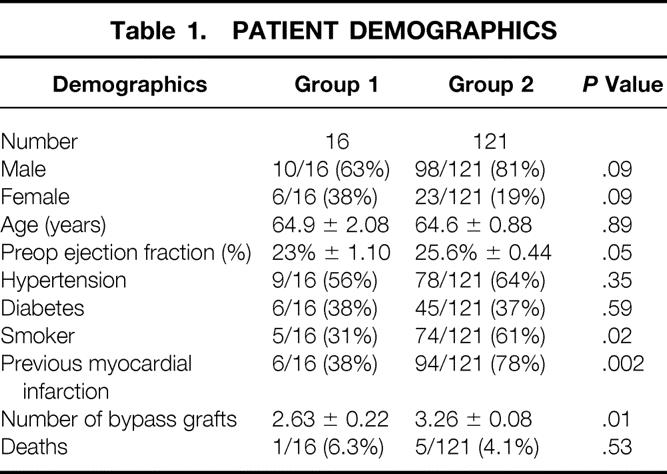

Patient demographics are depicted in Table 1. There were 16 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and severe (3–4+) MR who underwent mitral valve repair and concomitant CABG. Their ages ranged from 56 to 84 (mean 64.9) years. There were 10 men (62.5%) and 6 women (37.5%). One patient had undergone a four-vessel CABG through a median sternotomy 14 years before the current procedure. Six patients (38%) had a documented previous myocardial infarction, three (50%) less than 3 months before surgery. Eight patients (50%) were experiencing unstable angina at the time of surgery.

Table 1. PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS

The preoperative EF by echocardiography or cardiac catheterization was 15% to 30% (mean 23%). Ten patients (62.5%) had 4+ MR consistent with “severe MR” by our cardiology colleagues; the remaining six patients had 3+ MR consistent with “moderately severe MR.”

All patients underwent mitral valve repair with concomitant CABG in this series. No mitral valve replacements were performed. The average number of coronary artery anastomoses was 2.6 (range 1–4), with all but one patient receiving an internal mammary artery graft. Five patients underwent an additional procedure: three underwent a tricuspid valve repair (one of these patients also had an atrial septal defect closed) and two other patients underwent aortic valve replacements. Five patients required temporary insertion of an intraaortic balloon pump at the conclusion of surgery. All five of these were removed in the intensive care unit after hemodynamic stabilization.

The overall hospital death rate for group 1 was 6.3% (1/16). The one death occurred in a patient with a 15% EF and a recent (within 3 months) myocardial infarction. Postoperative renal failure and overwhelming sepsis developed in this patient, who died on postoperative day 17. This overall hospital death rate was not significantly different from the death rate of 4.1% (5/121) in group 2 (P = .44). These rates were not significantly different than the 8% rate for patients undergoing cardiac transplantation at the University of Virginia.

One-year follow-up of group 1 revealed a cumulative total of two deaths, for an 87% survival rate. The single late death was related to congestive heart failure 8 months after surgery. One patient was New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV at 1 year and was on the heart transplant list. The rest of the patients have had significant improvement with regard to their symptoms, and all were NYHA class I or II. This survival rate is similar to the 89% 1-year survival rate for heart transplant recipients at the University of Virginia.

There was no change in EF and minimal residual MR in group 1 based on postoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Conversely, the patients in group 2 had an average postoperative EF improvement of 11.7%.

DISCUSSION

In the setting of end-stage cardiomyopathy, MR has been a difficult entity to manage and leaves minimal treatment options. Patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and MR have a 2-year survival rate of 20%. 4 The surgical management of these patients, particularly those requiring both mitral valve surgery and concomitant CABG, has traditionally been associated with an increased surgical risk. 11 Clearly, these patients represent a substantially increased surgical risk compared with patients undergoing CABG alone or mitral valve surgery alone. 6 Fortunately, with the advances in myocardial protection and surgical techniques, some of these more difficult patients are now not only at lower surgical risk, but also are experiencing improvements in their symptomatic status. Given the donor shortage for cardiac transplantations, this has important implications as a surgical alternative to orthotopic heart transplantation.

Several studies have examined the surgical management of patients with MR and cardiomyopathy. Although dealing exclusively with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, Bolling et al 7 demonstrated that mitral valve repair in patients with end-stage heart failure improves not only survival but also cardiac function and symptomatic status. Chen et al 5 showed that open mitral valve repair in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy improves left ventricular function, symptoms, and overall survival.

The results of this study are consistent with previous work in this challenging subset of patients. However, unlike the previous studies, all patients in this study underwent both a mitral valve repair and concomitant CABG. In two studies by Bolling et al, 7,12 incidental CABG was performed in only 25% and 15% of patients, respectively, although none of these patients were thought to have ischemic cardiomyopathy. In the study by Chen et al, 5 77% of patients underwent concomitant CABG. In addition to the 100% concomitant CABG rate in our series, five of the patients in group 1 underwent an additional cardiac procedure. Despite the increased number of procedures and prolonged surgical time, this did not increase the surgical death rate. These results are also not significantly different from the group of patients in our study undergoing CABG alone in the setting of ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Several studies have demonstrated an improved functional status after mitral valve repair in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy. 12,13 Similarly, the majority of patients in this study had significant symptomatic improvement. However, this symptomatic improvement was not correlated with improvement in left ventricular function on transesophageal echocardiography performed immediately after surgical repair of the mitral valve. Conversely, in the patients in group 2 with ischemic cardiomyopathy who underwent CABG alone, there was an 11.7% EF improvement. Patients with poor preoperative ventricular function and predominately viable myocardium have a better outcome after bypass surgery. 14 However, we should not assume that the patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and severe MR have less viable myocardium. Given the presence of severe MR before surgery, the preoperative EF may have been overestimated and the left ventricular function was actually worse than originally thought.

The age range of patients in this study was 56 to 84 years, making it safe to conclude that this procedure is an excellent alternative for elderly patients who otherwise would not be candidates for cardiac transplantation. Conversely, 7 of the 16 patients (44%) were ages 56 to 61 years and would be candidates for the cardiac transplant list. Given the continued shortage of cardiac transplants and the significant costs associated with cardiac transplantation, this alternative seems all the more appealing. 15

The purpose of this study was to assess the surgical risk of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and severe MR undergoing mitral valve repair and concomitant CABG. We conclude that this procedure does not increase surgical risk and yields improvement in symptoms. The death rates compare favorably to both CABG alone and cardiac transplantation, thus offering a reasonable alternative for this patient population. Certainly the results of this study add to the increasing evidence that mitral valve repair in patients with cardiomyopathy, specifically those with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy, is not a prohibitive risk and is associated with improvement in symptoms.

Discussion

Dr. Harry A. Wellons, Jr. (Springfield, Illinois): Dr. Kron and his associates are to be complimented for focusing on a treatment strategy for a very severely ill group of patients that we, in our group, have intuitively accepted as a standard practice, although we have not documented those outcomes, as he has done here.

I had a short period of time to access our database to see what our results were, and I found that we had 109 patients for whom we had done coronary artery bypass grafting and mitral valve repair. It’s interesting that 16 of these patients had ejection fraction of less than 30%, which is similar to what is reported here. Now, I can’t say that these patients are comparable, because we didn’t look at the severity of mitral regurgitation and some of the other factors, but we did have one death in that group of patients. Because of this, we would agree that this approach is preferable to that of cardiac transplantation, and we don’t really have that option available to a lot of these patients. These are short-term results, however, and it would be interesting to know what the results are out 5 years or beyond.

I think as a treatment strategy it’s reasonable to compare these results to that of transplantation, as it’s the only reasonable option for these patients. In our area we have found that such treatment interventions plus improvement in management of heart failure have decreased the demand for cardiac transplantation.

Just reviewing our experience, it was of interest to us that the patients who had mitral valve repair plus coronary artery bypass grafting with ejection fractions of over 30% had pretty much the same mortality, and I wonder if that’s the experience that you have had at the University of Virginia.

Secondly, I’d like to ask this question: all patients in this series had severe mitral regurgitation, and I wonder what your treatment strategy would be in those patients that have mitral valve repair plus coronary bypass grafting but only have moderate mitral regurgitation.

Dr. Walter H. Merrill (Nashville, Tennessee): The authors are to be commended for presenting a stimulating and well-done report documenting their results in a difficult, high-risk group of patients. Their outcomes were excellent and are probably not exceeded by any other surgical experience. Clearly, through a retrospective analysis, they have been able to demonstrate that in their institution a small number of patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy accompanied by at least moderately severe mitral regurgitation have undergone revascularization and mitral valve repair with excellent survival and improvement in functional status.

It’s interesting to speculate as to whether or not these results can be maintained in a larger group of patients and maintained over a longer period of time and whether or not the excellent results could be duplicated in other institutions.

I have several questions for the authors:

How are patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy and mitral regurgitation evaluated and selected for operation? Presumably, some undergo revascularization and valve repair and some undergo transplantation. In other words, what are your exclusion criteria for revascularization and valve repair?

Secondly, have you utilized any form of physiologic assessment preoperatively, such as left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, dobutamine stress, thallium scintigraphy, or PET scanning to help determine patient suitability for revascularization and valve repair?

Finally, I note in your report that the number of bypass grafts performed was significantly lower in the revascularization plus valve repair group than in the group that underwent revascularization alone. Did you purposefully reduce the number of grafts in the study group in order to shorten the ischemia time?

Dr. Lenox D. Baker, Jr. (Norfolk, Virginia): I also enjoyed this retrospective analysis of this quite challenging group of patients, and I appreciate Dr. Gangemi sending me a copy to review, but I didn’t get it in time to look at what our results were. I’m probably glad I didn’t, because I echo Dr. Merrill—I think it would be hard to compare and do as well as this group has done.

With the millions of people having undergone either interventional or operative myocardial revascularization over the past two decades, it’s getting harder to die from ischemic heart disease acutely. And, therefore, the presentation of this type of patient presented in this study is clearly increasing in all of our practices.

I was surprised that only one patient had had previous bypass surgery in your group of 16, and wondered if you looked to see how many had previous interventional procedures. One of the things I have noticed in looking at patients who had multiple angioplasties and stents: as you watch the series of interventional cases go along, the ventricular ejection fraction goes down, and I’m wondering if some of these patients are not in your study.

Until Dr. Mancini and her colleagues working in immunobiology and genetics can perfect pig heart transplants, we are going to be increasingly challenged with these high-risk, very ill patients. Dr. Kron and his colleagues have done a service to expose the myth that these patients have an unacceptable mortality. I think the hesitancy to attempt to fix the mitral insufficiency of these patients reflects the inordinate mortality that we saw in the early and mid-1980s when we tried mitral valve replacement in these patients and especially with a poor ejection fraction.

Clearly, the advances made in mitral valve repair over the last decade have made this approach feasible, and the data presented here today certainly supports that. I have basically two questions.

One is, was there any attempt to stratify these patients looking at the presence, level, or reversibility of pulmonary hypertension? And did the patients who died or had poor results have more pulmonary hypertension than those with better results?

And, two, as the previous discussants have commented, you presented basically 1-year results in a small group of patients, which are not statistically significant. But have you looked at how these patients in the early years of this series have done over the past 3 to 4 years? I suspect that they will not compare favorably to patients fortunate enough to get a heart, either in quality of life or in mortality. Clearly, however, successfully repairing mitral regurgitation in these patients should allow them to have a better chance to survive long enough to get a transplant.

Dr. James J. Gangemi (Closing Discussion): I will try to be very concise with my answers. I appreciate the reviewers’ comments and questions for, again, this very difficult group of patients to deal with.

In terms of Dr. Wellon’s questions, unfortunately, we do not have the 5-year results of these patients. At this point we just have 1-year results; however, I do, fortunately, like most telecommunicators, have their phone numbers and in the upcoming years would like to follow these patients out and contact them to find out exactly their NYHA status and how they are doing clinically.

In terms of those patients who undergo mitral valve repair and concomitant CABGs with ejection fractions greater than 30%, obviously, for the focus of this study and our definition of ischemic cardiomyopathy, we kept the ejection fraction below 30%. However, we feel that in those patients with severe mitral regurgitation undergoing mitral valve repair with ejection fractions greater than 30%, we suspect our mortality is less than 4%.

In terms of those patients with mild to moderate mitral regurgitation, mitral valve repairs and concomitant CABGs, all patients undergo an intraoperative TEE preoperatively. And if these patients have mild to moderate or 1 to 2+ mitral regurgitation, these patients will not undergo a mitral valve repair. Generally, it’s for patients with 3 to 4+ mitral regurgitation.

In terms of Dr. Merrill’s questions, as far as our exclusion criteria, we generally will operate on patients in terms of doing CABGs on patients with good distal vessels. We also use thallium routinely on all of our patients preoperatively to assess who has true ischemia. We did not purposely reduce the number of CABGs performed in this group. Based on our retrospective studies, these are the numbers that we received.

In terms of Dr. Baker’s questions, we did have one patient out of those 16 patients who had a redo CABG.

As far as those patients who have had prior angioplasty, we do not know the specific results of those patients offhand. And we do not have any correlation at this point with respect to pulmonary hypertension and outcome.

Footnotes

Correspondence: James J. Gangemi, MD, MR 4 Building, Rm. 3116, Thoracic and Cardiovascular Research Laboratory, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville, VA 22903.

Presented at the 111th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 5–8, 1999, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

E-mail: jjg5d@virginia.edu

Accepted for publication December 1999.

References

- 1.Izumi S, Miyatake K, Beppu S, et al. Mechanism of mitral regurgitation in patients with myocardial infarction: a study using real-time two-dimensional Doppler flow imaging and echocardiography. Circulation 1987; 76:777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kono T, Sabbah HN, Rosman H, et al. Left ventricular shape is the primary determinant of functional mitral regurgitation in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:1594–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoran C, Yellin EL, Becker RM, et al. Dynamic aspects of acute mitral regurgitation: effects of ventricular volume, pressure, and contractility on the effective regurgitant orifice area. Circulation 1979; 60:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blondheim DS, Jacobs LE, Kotler MN, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy with mitral regurgitation: decreased survival despite a low frequency of left ventricular thrombus. Am Heart J 1991; 122:763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen FY, Adams DH, Aranki SF, et al. Mitral valve repair in cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1998; 98:II124–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn LH, Rizzo RJ, Adams DH, et al. The effect of pathophysiology on the surgical treatment of ischemic mitral regurgitation: operative and late risks of repair versus replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1995; 9:568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolling SF, Deeb GM, Brunsting LA, Bach DS. Early outcome of mitral valve reconstruction in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995; 109:676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanhaeke J, Flaemeng W, Sergeant P, et al. Emergency bypass surgery: late effect of size of infarction and ventricular function. Circulation 1985; 72:II179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kereiakes DJ, Topol EJ, George BS, et al. Emergency coronary bypass surgery preserves global and regional left ventricular function after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator therapy for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988; 11:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fucci C, Sandrelli L, Pardini A, et al. Improved results with mitral valve repair using new surgical techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1995; 9:621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn JH, Couper GS, Kinchla NM, Collins JJ Jr. Decreased operative risk of surgical treatment of mitral regurgitation with or without coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 16:1575–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolling SF, Pagani FD, Deeb GM, Bach DS. Intermediate-term outcome of mitral reconstruction in cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Surg 1998; 115:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay GL, Kay JH, Zubiate P, et al. Mitral valve repair for mitral regurgitation secondary to coronary artery disease. Circulation 1986; 74:I88–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagley PR, Beller GA, Watson DD, et al. Improved outcome after coronary bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and residual myocardial viability. Circulation 1997; 96:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Votapka TV, Swartz MT, Reedy JE, et al. Heart transplantation charges: status 1 versus status 2 patients. J Heart Lung Transpl 1995; 14:366–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]