Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the neoadjuvant use of a herpes simplex viral (HSV) amplicon vector expressing the murine interleukin-12 (IL-12) gene.

Summary Background Data

Surgery is the most effective therapy for hepatic malignancy. Recurrences, which are common, most often occur in the remnant liver and are due partly to growth of residual microscopic disease in the setting of postoperative host cellular immune dysfunction. The authors hypothesized that engineering tumors to secrete IL-12 in vivo would elicit an immune response directed at residual tumor and would reduce the incidence of recurrence after resection.

Methods

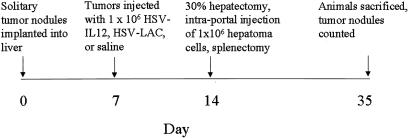

Solitary hepatomas were established in Buffalo rat livers and directly injected with 106 particles of HSV carrying the gene for IL-12, lacZ (β-galactosidase) or with saline. One week after injection, the animals were challenged with an intraportal injection of 106 tumor cells, with subsequent resection of the hepatic lobe containing the previously established macroscopic tumor nodule, recreating the clinical scenario of residual microscopic cancer.

Results

Hepatoma cells transfected with HSV–IL-12 produced high levels of IL-12 in vitro and in vivo. A significant local immune response developed, as evidenced by a progressive increase in the number of CD4(+) and CD8(+) lymphocytes in the tumor. Treatment of established hepatomas with HSV–IL-12 protected against growth of microscopic residual cancer after hepatic resection. Sixty-four percent of the animals treated with HSV–IL-12 had zero or one tumors compared with 30% of HSVlac-treated and 24% of saline-treated animals.

Conclusions

This neoadjuvant immune strategy may prove useful in reducing the incidence of cancer recurrence after hepatic resection.

Primary and secondary hepatic malignancies are responsible for more than 1 million deaths worldwide each year. 1,2 Hepatic resection remains the most effective therapy for selected patients, with long-term survival in one third. 1–4 However, even after complete resection, recurrent disease develops in nearly two thirds of patients, most often in the liver remnant and arising from residual microscopic cancer undetected at surgery. 5 There is also experimental evidence that postoperative changes, such as suppression of host cellular immune function, may stimulate growth of residual tumor cells. 6,7 Attempts to reduce the incidence of recurrent disease with adjuvant chemotherapy have had mixed results. 8,9 Stimulation of host immune effector mechanisms is a novel and potentially important method of eliminating microscopic residual disease and reducing the incidence of tumor recurrence after resection. 10–12

The most consistently successful immunotherapeutic strategy involves the use of immunostimulatory cytokine gene transfer to solid tumors. 13–16 Production of cytokines in proximity to putative tumor antigens has been shown experimentally to result in antitumor immunity that prevents subsequent development of cancer 14,16–23 and, in some studies, to eradicate established tumors. 14,16,19–24 The cytokines most often used in such strategies include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 10,18,23 interleukin 2 (IL-2), 14,16,19,20 and IL-12. 25,26 IL-12 is a heterodimeric protein that is a potent stimulator of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. 27–29 Most cytokine gene transfer approaches are limited by inefficient gene delivery to the tumor. The current studies used herpes simplex viral (HSV) amplicons as the vehicle for IL-12 gene transfer. These viral vectors are extremely efficient gene transfer vehicles for a variety of tumors, can accommodate a relatively large gene insert, and can achieve high levels of gene expression by direct injection into the tumor. 30,31

In the current experiments, HSV amplicon vectors carrying the IL-12 gene were used to treat established hepatic tumors before resection to determine whether such neoadjuvant therapy may inhibit the growth of microscopic tumors. This strategy was chosen for its potential clinical applicability. Administration of HSV vectors to gross tumors can be accomplished with ease, and the consequent immune reactions can potentially proceed unimpeded by the immunosuppressive effects of subsequent hepatectomy. Removal of the gross disease leaves only microscopic tumor targets in the liver remnant, thus simulating the actual clinical situation and providing the greatest likelihood of success for such immunotherapeutic strategies.

METHODS

Animals

Male Buffalo rats were housed in individual cages in a temperature-controlled (22°C) and humidity-controlled room with a 12-hour day/night cycle. Animals had free access to food and water. Animal weights were recorded at the beginning of each experiment and then at least every other day thereafter. All animals received care under approved protocols in compliance with Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Tumors

Morris hepatoma McA-RH7777 (ATCC No. CRL 1601, Rockville, MD), a syngeneic hepatoma cell line, was maintained in culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 4,500 g/L glucose, supplemented with 100 cc/L donor horse serum, 5% fetal calf serum, 50,000 units penicillin, and 50,000 units streptomycin. Cells were periodically implanted subcutaneously into rat flanks to ensure tumorigenicity. Portal injection of Morris hepatoma cells is a well-established model and reliably produces 10 to 20 hepatic tumors within the liver 3 weeks after injection.

HSV Vectors

The genes encoding the m35 and m40 fragments of murine IL-12 were directionally cloned into HSV/PRPUC 25 using appropriate restriction enzymes and packaged as previously described. 31–33 The m35 and m40 fragments are separated by an internal ribosome entry site, which allows intracellular translation of the intact molecule. HSV carrying the gene for β-galactosidase (HSVlac) was used as a control. The HSV vectors used in these experiments are replication-incompetent; the constructs have been previously characterized and described. 10,25

Surgical Procedures

All procedures were performed under pentobarbital anesthesia (25 mg/kg, given intraperitoneally) through an upper midline incision and under sterile conditions.

Establishment of Solitary Hepatic Tumors

Cultured Morris hepatoma cells were trypsinized and implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of rats (106 cells). Once the tumors had reached approximately 2 to 3 cm in diameter, they were harvested and cut into 2- to 3-mm pieces, which were then implanted under the capsule of the left hepatic lobe. The tumors were allowed to incorporate into the hepatic parenchyma for 1 week before additional investigations were performed, at which time the tumors generally measured 3 to 5 mm.

In Vivo β-Galactosidase Expression

Solitary hepatic tumors were established as described above and injected with 106 HSVlac in 50 μL calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The injections were made through a single puncture but with multiple passes to maximize viral dispersion. The tumors were harvested 48 hours after injection and placed in paraffin blocks. Sections 4 μm thick were cut and mounted on glass slides. The paraffin was then removed and the sections were hydrated and stained for β-galactosidase expression (X-Gal) as previously described. 34

In Vitro IL-12 Expression

To assess in vitro IL-12 production, 106 hepatoma cells/2 mL were placed in six-well plates, irradiated with 10,000 rad, and rested for 1 hour. Cells were then exposed to HSV–IL-12, HSVlac, or medium for 20 minutes at a multiplicity of infection equal to 1 (ratio of viral particles to target cells). The cells were then washed twice with media, and supernatants were harvested on days 1 through 7. IL-12 levels were measured using an m70 Quantikine Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) specific for the intact murine IL-12 molecule.

In Vivo IL-12 Expression

Solitary hepatic tumors were established in the liver and injected with HSV–IL-12, HSVlac, or saline (50 μL volume) 1 week later, as described above. Tumors were then harvested on days 0, 1, 2, 5, and 7 after injection and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. On the day of the assay, tumor samples were weighed and homogenized in 100 μL PBS. Specimens were then centrifuged in a Sorvall Discovery 100 ultracentrifuge (Sorvall Inc., Newtown, CT) at 35,000 rpm. All work was performed either on ice or at 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatants were harvested and assayed for IL-12 using the m70 Quantikine Kit specific for the intact murine IL-12. The results are expressed as picograms of IL-12/mg tissue.

Tumor Challenge After Partial Hepatectomy

The experimental protocol is summarized in Figure 1. The implanted tumors were injected with 106 particles of HSV–IL-12 or HSVlac in 50 μL calcium- and magnesium-free PBS or 50 μL saline. Injections were made through a single puncture but with multiple passes through the tumor to maximize viral dispersion. Animals with no evidence of tumor in the liver or those with peritoneal metastases were excluded from the experiment (approximately 5% of animals). One week after tumor injection, the animals were reexplored and underwent resection of the tumor-bearing left hepatic lobe (30% partial hepatectomy), followed by intrasplenic injection of 106 Morris hepatoma cells in 100 μL culture medium. The cells were injected during a period of at least 1 minute; the spleens were left in situ for 20 minutes after injection and were then resected. Care was taken to avoid spilling tumor cells into the peritoneal cavity. The animals were then weighed every other day and were killed approximately 3 weeks later, at which time the livers were harvested and the number of tumor nodules was recorded.

Figure 1. Experimental protocol, beginning with tumor implantation into the liver.

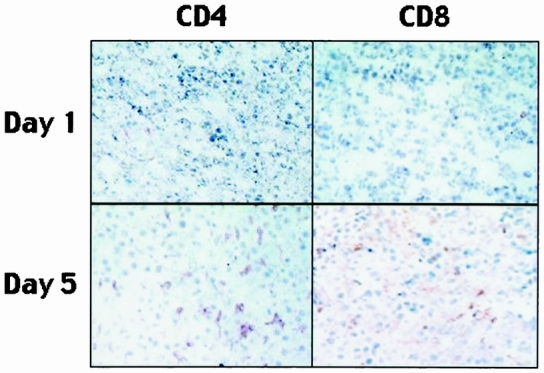

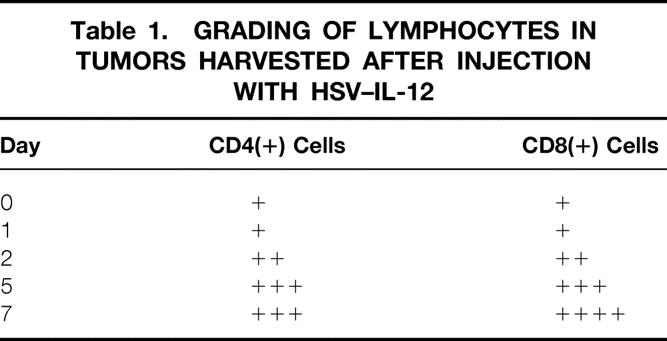

Immunohistochemical Staining for Intratumoral CD4(+) and CD8(+) Lymphocytes

Solitary hepatic tumors were established and injected with HSV–IL-12 and harvested at 0, 1, 2, 5, and 7 days after injection, as described above. The tumors were snap-frozen, embedded in Tissue-Tek (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) and stored at −20°C. The slides were then sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm and were used for immunoperoxidase staining for CD4(+) and CD8(+) lymphocytes. Sections of rat spleens served as positive controls. The anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody was obtained from Serotec (Raleigh, NC) and was used at a dilution of 1:20,000; the anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Caltag (Burlingame, CA) and was used at a dilution of 1:2,000. Briefly, the slides were washed in running water for 2 to 5 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with a 5-minute incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide and then washed in distilled water followed by PBS (pH 7.2). The slides were then placed in 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 minute followed by 2% BSA in PBS for 10 minutes. One hundred fifty microliters of the diluted primary antibody was then added and left overnight at 4°C. The primary antibody was then removed and the slides were washed three times in PBS for a total of 30 minutes. A 1:500 dilution of the secondary antibody (biotinylated antimouse, rat adsorbed; Vector Corp., Burlingame, CA) in 1% BSA in PBS was then added for 40 minutes at room temperature. After three washes in PBS (10 minutes each), a 1:500 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA) in 1% BSA in PBS was added for 30 minutes at room temperature. After further washing as above, the slides were transferred to a bath of diaminobenzidine in PBS for 15 minutes. The sections were then counterstained using Harris modified hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Atlanta, GA), decolorized, dehydrated, and permanently mounted.

The final stained sections were then reviewed by a pathologist (SM) masked to the experimental protocol, and each was scored for positive staining on a scale of 1+ to 4+.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean, unless otherwise indicated. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square analysis, continuous variables using the Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Establishment of Solitary Hepatic Tumors

Solitary hepatic tumors were established successfully in Buffalo rats (Fig. 2A). At the time of tumor injection (1 week after implantation), the tumors measured approximately 3 to 5 mm in diameter and were fully incorporated in the hepatic parenchyma. Animals with no obvious hepatic tumor and those with evidence of peritoneal tumor seeding were not used. The death rate related to the surgical procedures was 5% to 10%.

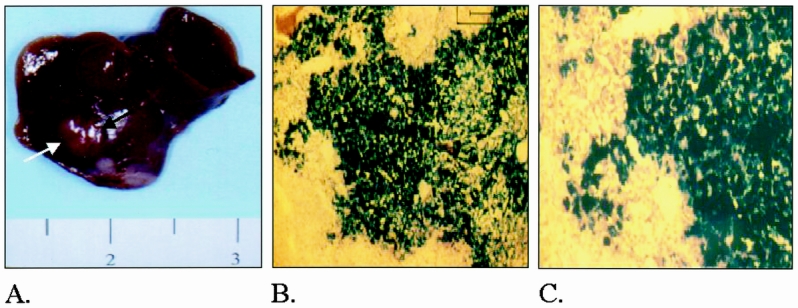

Figure 2. (A) Photograph illustrating a typical subcapsular tumor nodule 1 week after implantation. (B) Photomicrograph of tumor injected with HSVlac, fixed and stained for β-galactosidase expression. Low-power view (×10), 48 hours after direct injection. (C) Higher-power view (×20) of B.

In Vivo Expression of β-Galactosidase

Preliminary experiments had shown that HSVlac could transfect Morris hepatoma cells in vitro at a low multiplicity of infection and with high levels of gene expression. Direct injection of 106 particles of HSVlac into established hepatic tumors resulted in diffuse gene expression throughout the tumor (Figs. 2B and 2C).

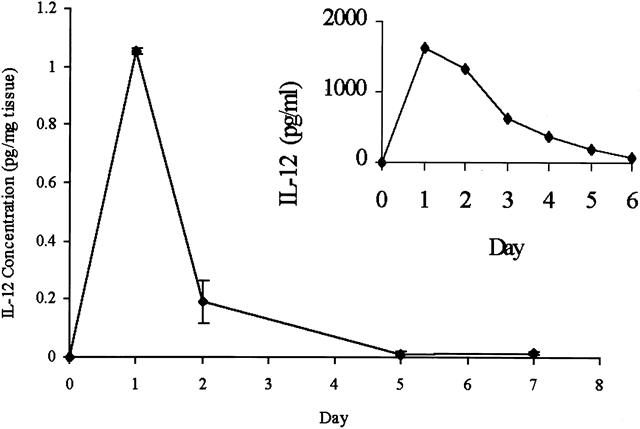

In Vitro and In Vivo IL-12 Expression

Peak secretion of IL-12 in vitro by irradiated hepatoma cells was observed 1 day after transfection (1,637 ± 248 pg/mL), with a gradual decline and return to baseline by day 6 (Fig. 3, inset). In vivo, a similar peak in IL-12 expression was observed at day 1, with a measurable return to baseline levels by day 5. Tumors injected with HSVlac or saline had no detectable levels of IL-12. Moreover, assays of serum in treated animals revealed no detectable change in circulating IL-12 levels (limit of detection = 2.5 pg/mL). IL-12 concentration in vivo was normalized to milligrams of tumor tissue; that in vitro is expressed as pg/mL medium.

Figure 3. Time course of in vivo interleukin-12 (IL-12) expression after tumor injection. Tumors injected with saline or HSVlac had no detectable levels of IL-12. (Inset) In vitro IL-12 expression in irradiated hepatoma cells over time.

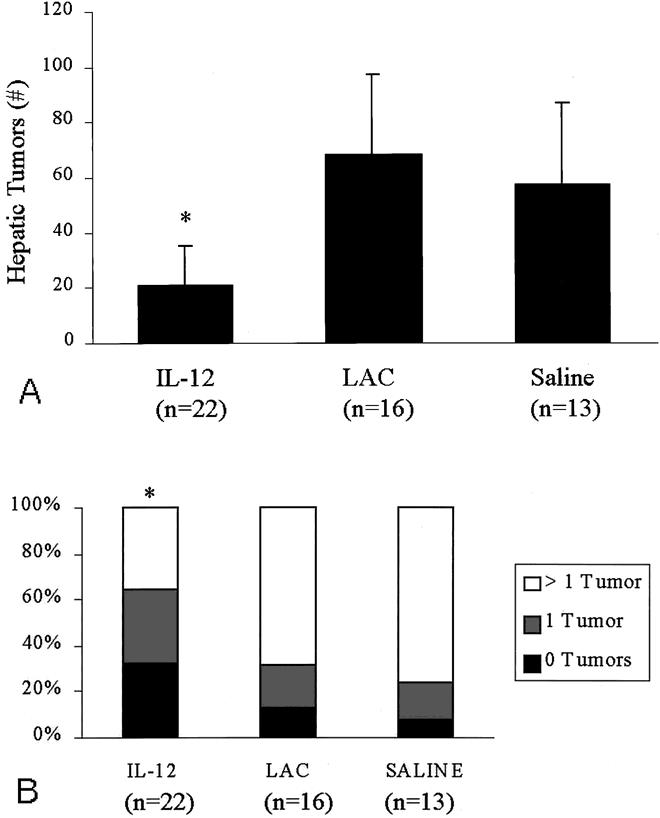

Tumor Challenge After Partial Hepatectomy

The number of hepatic tumors in the liver after partial hepatectomy and tumor cell challenge is summarized in Figure 4, which represents the combined results of three separate experiments. In animals treated with HSV–IL-12 before partial hepatectomy and tumor challenge, 21 ± 14 tumors developed (median = 1), which was significantly lower than in control animals treated with HSVlac (68 ± 29, median = 8, P < .05) or saline (57 ± 30, median = 10, P < .03;Fig. 4A). No tumors developed in 7 of 22 (32%) animals in the IL-12 group, compared with only 2 of 16 (12%) in the HSVlac group and 1 of 13 (8%) in the saline group. Overall, one or two tumors developed in 64% (14/22) of the animals in the IL-12 group compared with 30% of the HSVlac group (P < .05 vs. IL-12) and 24% of the saline-treated animals (P < .02 vs. IL-12;Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. (A) Number of hepatic tumors after pretreatment with HSV–IL-12, HSVlac, or saline, partial hepatectomy, and tumor cell challenge. The graph represents the combined results of three separate experiments. *P = .05 vs. HSVlac, P = .03 vs. saline. (B) Proportion of animals in each treatment group in which zero, one, or more than one hepatic tumors developed. The graph represents the combined results of three separate experiments. *P = .05 vs. HSVlac, P = .02 vs. saline.

Immunohistochemistry

Established tumors were harvested on days 0, 1, 2, 5, and 7 after injection with HSV–IL-12 and analyzed for changes in intratumoral lymphocytes using antibodies to CD4 and CD8. Representative stained sections from tumors 1 and 5 days after injection are shown in Figure 5. Grading of the stained sections by a pathologist masked to the experimental protocol revealed few CD4(+) and CD8(+) lymphocytes on days 0 and 1. However, both lymphocyte populations increased progressively beginning on day 2 and continuing through day 7 (Table 1).

Figure 5. Representative sections of tumor stained for CD4(+) and CD8(+) cell populations at 1 and 5 days after injection with HSV–IL-12. The positively stained cells appear light brown.

Table 1. GRADING OF LYMPHOCYTES IN TUMORS HARVESTED AFTER INJECTION WITH HSV–IL-12

DISCUSSION

Immunotherapy for cancer is based on the assumption that the host immune system can be manipulated to overcome tumor-related immunosuppressive mechanisms and to allow the host to recognize tumor-associated antigens. 35,36 Generation of antitumor immunity and host eradication of tumor are dependent on the consequent immune response. Cytokines are endogenous immunostimulatory proteins, many of which have potent experimental anticancer properties, 36 but their utility in eliciting antitumor immunity clinically is incompletely established. Systemically administered cytokines can result in significant tumor regression in a few patients, 36–38 but this is associated with serious side effects and also ignores the paracrine nature of these agents. Local production of cytokines at the site of tumor therefore may be a more appealing approach, potentially both more effective and less toxic. The current study used such an approach by eliciting local tumor production of IL-12, and it resulted in a reduction of tumor growth in a model simulating a commonly encountered clinical scenario.

Many previous experimental attempts at eliciting high local concentrations of cytokines at sites of tumor have used ex vivo gene transfer because of practical limitations imposed by gene transfer technology. Tumor cells thus modified in vitro are administered as tumor vaccines. Using relatively inefficient gene transfer techniques, ranging from physical to retroviral vectors, 39–46 tumor vaccines secreting cytokines such as IL-2, 14,16,19,20 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 23 IL-4, 21,47,48 and IL-12 25,26 have been investigated and have had varying degrees of success. Recently, more efficient viral vectors such as adenovirus, 49 vaccinia virus, 50–52 and HSV have made simple in vitro and in vivo gene transfer feasible. 25,53,54 Indeed, HSV vectors have particular advantages for use in the production of tumor vaccines because of their high gene transfer efficiency, the relatively large insert size that they can accommodate, and the transient nature of expression of the transferred gene. 10 The current data confirm these theoretical advantages by demonstrating the efficiency of HSV-mediated in vivo gene transfer and the resultant biologic effects, as well as the beneficial effects of local transient expression of the gene products in preventing high systemic levels of a potentially toxic cytokine. HSV vectors are highly efficient vehicles for in vivo transduction of established liver tumors: compared with other viral vectors, 10 to 1,000 times less HSV is usually required to achieve comparable levels of transduction and gene expression. 55 Further, recent data demonstrate that despite a relatively large particle size, HSV-derived viral particles transgress the tumor vascular endothelium with ease and can potentially be delivered by vascular perfusion. The practicality of percutaneous delivery of HSV-based viral vectors, either by direct tumoral injection or transcutaneous vascular perfusion, makes these vectors an enticing choice in neoadjuvant cytokine gene delivery to established tumors.

The choice of microscopic tumor targets in the current model of adjuvant therapy results from pessimism regarding the utility of a purely immune strategy against macroscopic solid tumors. Indeed, only a few prior experimental studies have found tumor vaccines to be effective against macroscopic tumors, 14,16,19,20,22,23 and no human study has clearly demonstrated effectiveness of tumor vaccines against any solid tumor other than melanoma. There is much greater enthusiasm for using immunotherapeutic strategies as an adjuvant to resection of all gross disease. Patients with hepatic malignancies who are candidates for resection are an ideal group for such adjuvant therapy for several reasons. First, these patients have a high likelihood of residual microscopic disease. Second, hepatic tumors are readily accessible percutaneously, which would allow facile delivery of viral vectors for tumor transduction and in situ tumor vaccine production. Third, the tumor vaccine strategy would be used to treat residual microscopic tumor cells as an adjuvant to resection, where such an approach is more likely to be successful than as treatment for macroscopic tumors. In addition, delivery of the immunostimulatory cytokine would be done before liver resection, thus avoiding the potential problem of postoperative immunosuppression. The favorable results in the current study support this proposed strategy of neoadjuvant use of cytokine-secreting tumor cells in vivo.

Interleukin-12 was chosen as the therapeutic cytokine because it is one of the key cytokines involved in the development of an antitumor response. 27–29 IL-12 mediates several important immunologic processes, including stimulation of interferon-γ synthesis and natural killer cell function, 56 as well as stimulation of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte effector functions. 27,57,58 Some studies have documented impaired production of IL-12 in patients with a variety of malignancies, and this appears to be associated with an impaired T-helper cell 1 (Th1)-mediated tumor response and to correlate with extent of disease. 59,60 In animal models, IL-12–secreting tumor vaccines have been shown to cause regression of established tumors and to suppress the growth of parental tumor cells. 25,27 Further, Rakhmilevich et al, 61 using gene gun technology, transfected dermal tumors with a variety of immunostimulatory cytokine genes and found that IL-12 was the most effective in causing tumor regression and was the only cytokine investigated that was capable of causing tumor regression at distant sites. In addition, data from our laboratory have suggested that IL-12–secreting tumor vaccines produced by ex vivo gene transfer can induce lasting, tumor-specific immunity. 25 The current data would indicate that in vivo IL-12 gene transfer to tumor is also effective in generating biologically relevant immunologic effects. In the present study, we documented a marked increase in both CD8(+) and CD4(+) lymphocytes in the tumor beginning 24 hours after the peak in IL-12 expression. These results are consistent with those of other studies that have demonstrated a dependence of IL-12–mediated immunostimulation on CD8(+) and CD4(+) cells. 62,63 Even more importantly, treatment with HSV–IL-12 significantly altered growth of the microscopic residual tumor.

The observed antitumor effects appear to be specifically the result of IL-12 expression in the tumor and not merely the result of the presence of HSV, because injection of HSVlac did not offer similar protection, even though transduction by HSVlac was documented diffusely throughout the tumor. Moreover, the biologic effects appear to have resulted mainly from increased local levels of IL-12, because no increase in circulating IL-12 levels was observed. Although HSV–IL-12 treatment in the current study produced a significant number of cures, cure was not universal. Future studies are needed to determine whether additional immunostimulatory strategies may improve on these results. A combination of chemokines to attract immune effector cells to sites of putative tumor antigens, 64 along with adhesion molecules or costimulatory molecules to bind such effector cells at these sites 24,65 may complement local expression of immunostimulatory cytokines to enhance antitumor efficacy. HSV vectors would also be promising vehicles for such multigene transfer strategies. Already, there are data from ex vivo gene transfer studies that HSV vectors rapidly effect multigene transfer to produce tumor vaccines secreting multiple cytokines and result in highly synergistic actions. 25 The high likelihood that such multigene transduction may be accomplished for synergistic actions in vivo awaits experimental evaluation.

In conclusion, HSV vectors can efficiently and effectively transduce established hepatic tumors. In this clinically relevant model of liver cancer, treatment of established tumors with HSV–IL-12 resulted in high local levels of protein expression and increased intratumoral CD8(+) and CD4(+) lymphocyte populations. Treatment of tumors with HSV–IL-12 significantly reduced the growth of residual microscopic cancer at the time of resection of the parental tumor, suggesting a tumor-specific memory response. Because of its ease of use and apparent efficacy, such a neoadjuvant strategy may have clinical applications. These data, therefore, encourage examination of such a neoadjuvant strategy in conjunction with hepatic resection for tumor in humans.

Discussion

Dr. Timothy J. Eberlein (St. Louis, Missouri): Hepatic resection remains the most effective treatment for patients with metastatic disease confined to the liver. However, even after complete resection with negative margins, the overwhelming majority of these patients will have recurrence, both in and out of the liver parenchyma. Systemic chemotherapy has had limited success, and perioperative regional chemotherapy is still under active investigation, although with promising results. Therefore, utilization of a process to stimulate the host immune response might represent a promising alternative strategy.

This elegant study by Dr. Jarnagin and colleagues uses a unique approach to attempt to stimulate a host antitumor response. The current study employs herpes simplex amplicons as the vehicle for IL-12 gene therapy. This approach has several theoretical advantages, the first of which is that there is a high gene transfer efficiency that allows for in vivo transduction of established tumor, and thus, delivery can be accomplished by percutaneous delivery or transcutaneous vascular perfusion, both of which may have human applicability.

The second is that these vectors can accommodate relatively large insert size. And while this study looks at IL-12 alone, the combination of cytokines or other genes could be utilized. These vectors are replication-competent vectors. My first question, therefore, is what is the long-term consequence of injecting these vectors into humans, especially for repetitive treatments?

In the present study, a simple tumor mass was percutaneously injected with the vector, then underwent resection, followed by injection of hepatoma cells intersplenic. The animals were then splenectomized and 3 weeks later sacrificed, and the liver tumor nodules were recorded. My second question: Why was the splenectomy performed, and what potential impact on host immune response might it have? Obviously, in our patient population, we will most likely not be performing splenectomies after the gene therapy.

There was an impressive reduction in tumor nodules in the animals, and in fact, there are even some animals who have “cures.” However, in the experimental group, there is residual significant tumor burden. My third group of questions are: Have the authors studied similar animals over a longer term, that is, longer than the 3-week follow-up in the present study? While they have clear reduction in tumor burden in the liver from this gene therapy, is the antitumor effect truly systemic? This is particularly important because most patients who recur will do so with some disease outside the liver.

In the paper’s discussion, the authors speculate they may be able to improve results with the HSV vectors containing multiple cytokines as well as adhesion molecules or costimulatory molecules. How would this technically be accomplished?

Finally, the mechanism of the tumor reduction suggested by the authors appears to be the level of production locally of IL-12, which causes influx of host CD-4 and CD-8 lymphocytes into the tumor nodule. My question is: Have the authors looked at the local immune response to the tumor nodules after the intersplenic tumor injection?

As I read the manuscript, the authors induced the lymphocyte infiltration over time after the HSV IL-12 injection in the singular tumor nodule that was then, in the further experiments, resected. Have you looked at the immune response of the animals who were cured compared to the animals that still have tumor nodules in the treatment group? Is there a difference in the quality or quantity of the immune response?

Once again, I want to congratulate the authors for an excellent and innovative study and for providing us with their well-written manuscript beforehand. We will look forward to further innovative approaches of this difficult clinical problem from this group.

Dr. A. Osama Gaber (Memphis, Tennessee): I congratulate the authors on a very novel means of trying to prevent tumor recurrences after hepatic resections. I have two questions, but I have not been privy to the manuscript, so maybe the authors can enlighten us on it.

The first is that they talk about the degree to which the tumor secretes the IL-12 after the HSV virus vector insertion, and I wondered if that is measurable and are there degrees to which the recurrence rates are not going to happen, based on how much IL-12 has been secreted? How do we do that clinically? Because clearly, in the hepatic nodules, it’s the idea of being able to get enough infiltration of the vector into the tumor cells. It will be a little bit more complex than a smaller tumor in the animals.

Secondly, the authors say that the mechanism is by induction of some sort of immune response to the tumor, and I realize that there was infiltration in the liver tumors themselves by the CD-4 and CD-8, but was there an actual systemic increase in the immune response? Did they measure anything in the animals that were cured that differentiates them from the animals that were not?

Dr. C. Wright Pinson (Nashville, Tennessee): One has to admire the goal the authors have pursued in this project, namely, an alternative form of adjuvant therapy. The concept of developing a tumor vaccine is very attractive.

The issue of sustained adequate copies of the transvected gene, which I think is what Dr. Gaber was just getting at, is in question. Do you think repetitive injection into the tumors would help to stimulate IL-12 production, and would longer sustained periods of IL-12 production be of benefit here?

The next question I have is why does the expression of IL-12, a relatively generic cytokine here, by the tumor cells make them an effective vaccine? I really would like to have that point clarified.

Finally, I am very interested in where you see your next steps. I presume you are not ready to start injecting HSV into patients just yet, but tell us where you think this is going clinically.

Dr. Yuman Fong (Closing Discussion): Let me answer Tim’s questions first. As related to the vectors themselves, Tim asked whether these were replication-competent viruses and what the long-term consequences would be. In fact, these are replication-incompetent. In my laboratory, we use three types of herpes-based viruses for therapy. These are the amplicon vectors. We also use disc vectors, which replicate once and can no longer replicate after that, and replication-competent herpes viruses for oncolysis, which are competent viruses that seek out tumor cells and kill them. The class that we used for these particular experiments today are amplicon vectors. They are incompetent in terms of replication. They are just meant as gene transfer vehicles, and they have no long-term consequences whatsoever. That’s what makes these so attractive as gene transfer vehicles for immunotherapy. That’s because of their potential safety compared to the other classes of vectors.

Secondly, he asked why we did the splenectomy. The reason is because the model we used of challenging the animals by intersplenic injection of tumor is actually one that was popularized by Drs. Rosenberg and Lafreniere in their publication in the JNCI, where they injected tumor cells in the spleen, and it seeds the liver beautifully. Unfortunately, there is always residual tumor inside the spleen, and if you leave the spleen intact, what happens is that it overgrows the spleen and causes other problems for the animals. And so the standard procedure for this model is to do a splenectomy and, unfortunately, that does limit our ability to do CTL assays and other assays that require splenocytes to evaluate the systemic response. At times, we do direct portal injections to be able to save the splenocytes for that reason.

In terms of long-term effects of such therapies and whether they are truly systemic, we believe so. The study design here is for resection of a macroscopic tumor, and therefore, there are no residual tumor cells that can be producing IL-12. Effects on the residual microscopic disease have to be something residual in the animal and systemic. In addition, in animals with multiple flank tumors, we have treated a single flank tumor with HSV carrying various cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules, and have seen other tumors, not treated, shrink in size. So we believe such an approach can generate a systemic response that is seen at other tumor sites.

In terms of the questions about IL-12 secretion, the approach here is actually not to generate sustained IL-12 secretion. If that were the goal, we would be thinking about putting IL-12 into infusion pumps to give interarterially or some other way. The whole theory behind the immunotherapy by making tumor vaccines that generate cytokines is to put cytokines at high levels near putative tumor antigens for just a brief period of time. That’s why these amplicon vectors are so great, because they have a high gene transduction efficiency; local cytokine levels and other levels are very high for a brief period of time, but then they disappear because the genes that are transferred remain episomal. They are not incorporated into the genome of the cell, and therefore, potential future toxicities are eliminated from that standpoint.

In terms of the questions about why IL-12, IL-12 is a cytokine that has been shown to generate various systemic immune responses that are important for tumor rejection, including generation of gamma interferon and stimulation of CTLs. In addition to IL-12, however, we also have an entire armamentarium of other cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules that we have put into these same vectors, ranging from IL-2 to IL-12, to GM-CSF and other chemokines. We believe that ultimately there is a combination of these that will probably be clinically useful. In fact, some of those experiments using combinations of chemokines to attract immune cells to sites of tumor, adhesion molecules to bind those immune cells at sites of putative tumor antigen, and activating cytokines in those local areas to try to stimulate immune cells, are the combinations we are currently trying. I hope to have some of those results to show you in the near future.

Footnotes

Correspondence: William R. Jarnagin, MD, Dept. of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave., New York, NY 10021.

Presented at the 111th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 5–8, 1999, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Supported in part by grants RO1CA72632–01A1, RO1CA/DK80982–01, and RO1CA76416–01 from the National Institutes of Health and MBC-99366 from the American Cancer Society.

E-mail: jarnagiw@mskcc.org

Accepted for publication December 1999.

References

- 1.Fan S, Lai ECS, Lo C, Ng IOL, Wong J. Hospital mortality of major hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with cirrhosis. Arch Surg 1995; 130:198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun R, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 1999; 230:309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Paul M. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg 1995; 19:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. Cancer 1996; 77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Cohen AM. Surgical treatment of colorectal metastases to the liver. CA 1995; 45:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher ER, Fisher B. Experimental studies of factors influencing hepatic metastases. Cancer 1959; 12:929–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karpoff HM, Tung C, Ng B, Fong Y. Interferon gamma protects against hepatic tumor growth in rats by increasing Kupffer cell tumoricidal activity. Hepatology 1996; 24:374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenz M, Muller HH, Schramm H, et al. Randomized trial of surgery versus surgery followed by adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid for liver metastases of colorectal cancer. German Cooperative on Liver Metastases (Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen). Ann Surg 1998; 228:756–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemeny N, Huang Y, Cohen AM, et al. Randomized study of hepatic arterial infusion and systemic chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy alone as adjuvant treatment following resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:2039–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karpoff HM, D’Angelica M, Blair S, Brownlee MD, Federoff H, Fong Y. Prevention of hepatic tumor metastases in rats with herpes viral vaccines and gamma-interferon. J Clin Invest 1997; 99:799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fidler IJ. Systemic macrophage activation with liposome-entrapped immunomodulators for therapy of cancer metastasis. Res Immunol 1996; 143:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawata A, Une Y, Hosokawa M, et al. Adjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Adriamycin, interleukin-2, and lymphokine-activated killer cells versus Adriamycin alone. Am J Clin Oncol 1995; 18:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavallo F, Giovarelli M, Gulino A, et al. Role of neutrophils and CD4+ T lymphocytes in the primary and memory response to nonimmunogenic murine mammary adenocarcinoma made immunogenic by IL-2 gene. J Immunol 1991; 149:3627–3635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor J, Bannerji R, Saito S, Heston W, Fair W, Gilboa E. Regression of bladder tumors in mice treated with interleukin-2 gene-modified tumor cells. J Exp Med 1993; 177:1127–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allione A, Consalvo M, Nanni P, et al. Immunizing and curative potential of replicating and nonreplicating murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells engineered with interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor alpha, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, and gamma-interferon gene or admixed with conventional adjuvants. Cancer Res 1994; 54:6022–6026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito S, Bannerji R, Gansbacher B, et al. Immunotherapy of bladder cancer with cytokine gene-modified tumor vaccines. Cancer Res 1994; 54:3516–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gansbacher B, Zier K, Daniels B, Cronin K, Bannerji R, Gilboa E. Interleukin-2 gene transfer into tumor cells abrogates tumorigenicity and induces protective immunity. J Exp Med 1990; 172:1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo MP, Ferrari G, Stoppacciaro A, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor gene transfer suppresses tumorigenicity of a murine adenocarcinoma in vivo. J Exp Med 1991; 173:889–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porgador A, Tzehoval E, Vadai E, Feldman M, Eisenbach L. Immunotherapy via gene therapy: comparison of the effects of tumor cells transduced with the interleukin-2, interleukin-6, or interferon-lambda genes. J Immunother 1993; 14:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieweg J, Rosenthal FM, Bannerji R, et al. Immunotherapy of prostate cancer in the Dunning rat model: use of cytokine gene modified tumor vaccines. Cancer Res 1994; 54:1760–1765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golumbek PT, Lazenby AJ, Levitsky HI, et al. Treatment of established renal cancer by tumor cells engineered to secrete interleukin-4. Science 1991; 254:713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porgador A, Tzehoval E, Katz A, et al. Interleukin 6 gene transfection into Lewis lung carcinoma tumor cells suppresses the malignant phenotype and confers immunotherapeutic competence against parental metastatic cells. Cancer Res 1992; 52:3679–3686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90:3539–3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Angelica M, Tumg C, Allen P, et al. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-mediated ICAM-1 gene transfer abrogates tumorigenicity and induces anti-tumor immunity. Mol Med 1999; 5:606–616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karpoff HM, Kooby D, D’Angelica M, et al. Efficient cotransduction of tumors by multiple herpes simplex vectors: implications for tumor vaccine production. Cancer Gene Ther (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Tahara H, Zeh HJ III, Storkus WJ, et al. Fibroblasts genetically engineered to secrete interleukin 12 can suppress tumor growth and induce antitumor immunity to a murine melanoma in vivo. Cancer Res 1994; 54:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruna MJ, Lusitro L, Warrier RR, et al. Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of interleukin-12 against murine tumors. J Exp Med 1993; 178:1223–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vagliani M, Rodolfo M, Cavallo F, et al. Interleukin 12 potentiates the curative effect of a vaccine based on. Cancer Res 1996; 56:467–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao JB, Chamberlain RS, Bronte V, et al. IL-12 is an effective adjuvant to recombinant vaccinia virus-based tumor vaccines: enhancement by simultaneous B7–1 expression. J Immunol 1996; 156:3357–3365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramm CM, Chase M, Herrlinger U, et al. Therapeutic efficiency and safety of a second-generation replication-conditional HSV1 vector for brain tumor gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 1997; 8:2057–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Federoff HJ. Growth of replication defective herpes virus amplicon vectors and their use for gene transfer. In: Spector DL, Leinwand L, Goldman R, eds. Cell Biology: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1996.

- 32.Geller AI, Keyomarsi K, Bryan J, Pardee AB. An efficient deletion mutant packaging system for defective herpes simplex virus vectors: potential applications to human gene therapy and neuronal physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:8950–8954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geller AI, Breakefield XO. A defective HSV-1 vector expresses Escherichia coli B-galactosidase in cultured peripheral neurons. Science 1988; 241:1667–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong Y, Federoff HJ, Brownlee M, Blumberg D, Blumgart LH, Brennan MF. Rapid and efficient gene transfer in human hepatocytes by herpes viral vectors. Hepatology 1995; 22:723–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ley V, Langlade-Demoyen P, Kourilsky P, Larrson-Sciard E. Interleukin 2-dependent activation of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. Eur J Immunol 1991; 21:851–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin JT. Interleukin-2: its biology and clinical application in patients with cancer. Cancer Invest 1993; 11:460–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Sci Am 1990; 262:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Yang JC, et al. Prospective randomized trial of high-dose interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with lymphokine-activated killer cells for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. J NCI 1993; 85:622–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahara H, Zitvogel L, Storkus WJ, et al. Effective eradication of established murine tumors with IL-12 gene therapy using a polycistronic retroviral vector. J Immunol 1995; 154:6466–6474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahuja SS, Mummidi S, Malech HL, Ahuha SK. Human dendritic cell (DC)-based anti-infective therapy: engineering DCs to secrete functional IFN-γ and IL-12. J Immunol 1998; 161:868–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers JN, Mank Seymour A, Zitvogel L, et al. Interleukin-12 gene therapy prevents establishment of SCC VII squamous cell carcinomas, inhibits tumor growth, and elicits long-term antitumor immunity in syngeneic C3H mice. Laryngoscope 1998; 108:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsumoto G, Sunamura M, Shimamura H, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy using fibroblasts genetically engineered to secrete interleukin 12 prevents recurrence after surgical resection of established tumors in a murine adenocarcinoma model. Surgery 1999; 125:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirkwood JM, Ernstoff MS. Interferons in the treatment of human cancer. J Clin Oncol 1984; 2:336–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reinhart JJ, Malspeis L, Young D, Neidhart JA. Phase I-II trial of human recombinant beta-interferon serine in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 1986; 46:5364–5367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vadhan-Raj S, Al-Katib A, Bhalla R, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant interferon gamma in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1986; 4:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbruzzese JL, Levin B, Ajani JA, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant human gamma-interferon and recombinant human tumor necrosis factor in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Res 1989; 49:4057–4061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tepper RI, Pattengale PK, Leder P. Murine interleukin-4 displays potent anti-tumor activity in vivo. Cell 1989; 57:503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tepper RI, Coffman RL, Leder P. An eosinophil-dependent mechanism for the antitumor effect of interleukin-4. Science 1992; 257:548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen L, Chen D, Block E, O’Donnel M, Kufe DW, Clinton SK. Eradication of murine bladder carcinoma by intratumor injection of bicistronic adenoviral vector carrying cDNAs for the IL-12 heterodimer and its inhibition by the IL-12 p40 subunit homodimer. J Immunol 1997; 159:351–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lattime EC, Lee SS, Eisenlohr LC, Mastrangelo MJ. In situ cytokine gene transfection using vaccinia virus vectors. Semin Oncol 1996; 23:88–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogan SP, Foster PS, Tan X, Ramsay AJ. Mucosal IL-12 gene delivery inhibits allergic airway disease and restores local antiviral immunity. Eur J Immunol 1998; 28:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson BW, Mukherjee SA, Davidson A, et al. Cytokine gene therapy or infusion as treatment for solid human cancer. J Immunother 1998; 21:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D’Angelica M, Karpoff H, Halterman M, et al. In vivo interleukin-2 gene therapy of established tumors with herpes simplex amplicon vectors. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1999; 47:265–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breakefield XO. Gene delivery into the brain using virus vectors. Nature Gen 1993; 3:187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tung C, Federoff HJ, Brownlee M, et al. Rapid production of IL-2 secreting tumor cells by HSV-mediated gene transfer: implications for autologous vaccine production. Hum Gene Ther 1996; 7:2217–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunda MJ. Interleukin-12. J Leukocyte Biol 1994; 55:280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gately MK, Wolitzky AG, Quinn PM, Chizzonite R. Regulation of human cytolytic lymphocyte responses by interleukin-12. Cell Immunol 1992; 143:127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams NJ, Harvey JJ, Booth RF, Knight SC. Interleukin-12 restores dendritic cell function and cell-mediated immunity in retrovirus-infected mice. Cell Immunol 1998; 183:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Hara RJ, Greenman J, MacDonald AW, et al. Advanced colorectal cancer is associated with impaired interleukin 12 and enhanced interleukin 10 production. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4:1943–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Hara RJ, Greenman J, Drew PJ, et al. Impaired interleukin-12 production is associated with a defective anti-tumor response in colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41:460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rakhmilevich AL, Janssen K, Turner J, Culp J, Yang NS. Cytokine gene therapy of cancer using gene gun technology: superior antitumor activity of interleukin-12. Hum Gene Ther 1997; 8:1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott P. IL-12: initiation cytokine for cell-mediated immunity. Science 1993; 260:496–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, OGarra A, Murphy KM. Development of TA1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science 1993; 260:547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liao F, Rabin RL, Yannelli JR, Koniaris LG, Vanguri P, Farber JM. Human Mig chemokine: biochemical and functional characterization. J Exp Med 1995; 182:1301–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Townsend SE, Allison JP. Tumor rejection after direct costimulation of CD8+ T cells by B7-transfected melanoma cells. Science 1993; 259:368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]