Abstract

Objective

To assess long-term outcomes after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) for chronic ulcerative colitis (CUC) with specific emphasis on patient sex, childbirth, and age.

Summary Background Data

Childbirth and the process of aging affect pelvic floor and anal sphincter function independently. Early function after IPAA is good for most patients. Nonetheless, there are concerns about the impact of the aging process as well as pregnancy on long-term functional outcomes after IPAA.

Methods

Functional outcomes using a standardized questionnaire were prospectively assessed for each patient on an annual basis.

Results

Of the 1,454 patients who underwent IPAA for CUC between 1981 and 1994, 1,386 were part of this study. Median age was 32 years. Median length of follow-up was 8 years. Pelvic sepsis was the primary cause of pouch failure irrespective of sex or age. Functional outcomes were comparable between men and women. Eighty-five women who became pregnant after IPAA had pouch function, which was comparable with women who did not have a child. Daytime and nocturnal incontinence affected older patients more frequently than younger ones. Incontinence became more common the longer the follow-up in older patients, but this was not found in younger patients. Poor anal function led to pouch excision in only 3 of 204 older patients.

Conclusions

Incontinence rates were significantly higher in older patients after IPAA for CUC compared with younger patients. However, this did not contribute to a greater risk of pouch failure in these older patients. Patient sex and uncomplicated childbirth did not affect long-term functional outcomes.

Early reports of function after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) for chronic ulcerative colitis (CUC) have indicated favorable outcomes, with an excellent quality of life for more than 90% of patients. 1–3 Areas of concern remain, however, regarding long-term functional outcome after vaginal delivery and the natural aging process, which may affect pelvic floor function regardless of sex. 4,5

Chronic ulcerative colitis has a bimodal distribution of incidence based on age, with a peak at 25 years and a second peak at 60 years. 6 A selected group of older patients choose, in the absence of contraindications, to undergo IPAA. Short-term follow-up has shown that such patients may have comparable or only marginally worse functional outcomes compared with younger patients. 7–9

Our aim was to assess long-term outcomes after IPAA for CUC with specific reference to the impact of age, aging, and childbirth to determine how these factors affect the incidence of pouch failure.

METHODS

Between January 1981 and December 1994, 762 men and 692 women were identified from the Mayo Ileal Pouch Registry as having undergone proctocolectomy, endoanal mucosal resection, and hand-sewn ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis for CUC. Ethical permission to review patient records was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. All patient data, demographics, preoperative status, surgical details, and postoperative functional outcomes and satisfaction were recorded prospectively. Patients were asked to complete a detailed questionnaire before surgery and annually after surgery. The operations were performed by seven consultant surgeons. Postoperative follow-up for at least 5 years was available in 1,386 of the patients.

Incontinence was reported as never, occasional (spotting of mucus less than twice per week), and frequent (more frequent spotting or actual fecal incontinence). Pouchitis was defined by the clinical findings of fever, chills, and crampy abdominal pain accompanied by bloody diarrhea, which responded promptly to treatment with oral antibiotics. Pouch failure was defined as the need for pouch excision or for a defunctioning ileostomy for more than 12 months with the pouch in situ.

Results are expressed as median values with ranges. For the age comparison, patients were grouped according to their age at the time of IPAA. Proportions of events were compared between the two groups by the chi-square or the Fisher exact test. Comparison of ordinal variables and changes over time were assessed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Cumulative probabilities of pouchitis and pouch failure were calculated using the Kaplan-Maier method. Statistical significance was attributed at the 5% level.

RESULTS

Of the patients with complete follow-up, 1,310 had a J pouch, 57 an S pouch, and 17 a W pouch, and 2 had another pouch configuration. The median age at the time of IPAA was 32 (range 5–65) years. There were 1,182 patients younger than 45 years (median age 31 years) and 204 patients more than 45 years (median age 46 years) at the time of surgery. The median length of follow-up was 8 (range, 5–17) years. Follow-up for 12 years or more was available in 413 patients (198 women). Thirty-three of these patients (15 women) were older than 45 years and 380 (170 women) were younger than 45 years at the time of IPAA.

Preoperative Function

The number of stools per 24 hours before IPAA was 10 (range 1–35). Occasional preoperative incontinence affected 99 patients (8%), whereas frequent incontinence affected 79 patients (7%).

Functional Outcomes

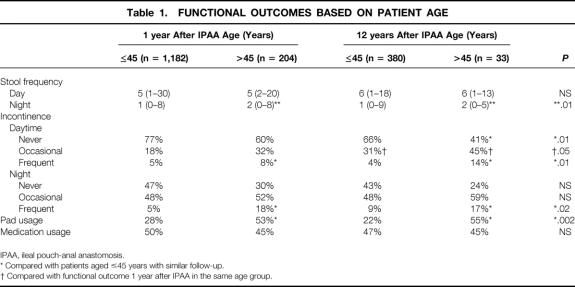

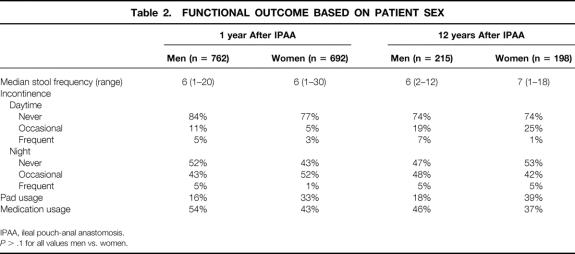

These results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Nocturnal stool frequency, fecal incontinence, protective pad use, and constipating medication requirements were higher in patients who were older than 45 at the time of IPAA. Spotting and frequent incontinence became more common among older patients as follow-up lengthened. As they grew older, occasional incontinence became more common among patients who were 45 years or younger at the time of IPAA. Functional outcomes were comparable between men and women.

Table 1. FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMES BASED ON PATIENT AGE

IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

* Compared with patients aged ≤45 years with similar follow-up.

† Compared with functional outcome 1 year after IPAA in the same age group.

Table 2. FUNCTIONAL OUTCOME BASED ON PATIENT SEX

IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

P > .1 for all values men vs. women.

Risk of Pouchitis

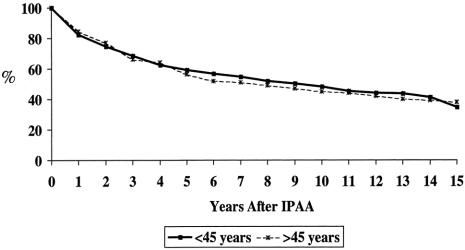

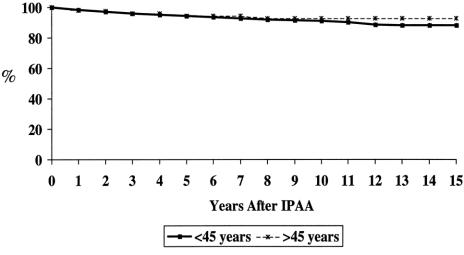

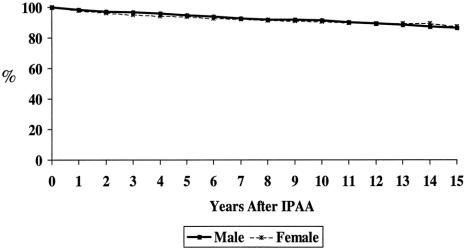

The cumulative risk of developing pouchitis in older versus younger patients is shown in Figure 1; the risk in men versus women is shown in Figure 2. This risk increased with length of follow-up irrespective of patient age or sex. Most episodes of pouchitis were self-limiting; overall, chronic pouchitis affected 10% of all patients.

Figure 1. Probability of no pouchitis: older patients versus younger patients.

Figure 2. Probability of no pouchitis: men versus women.

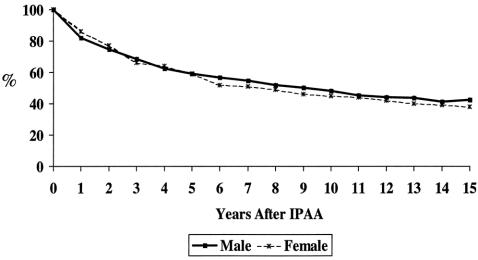

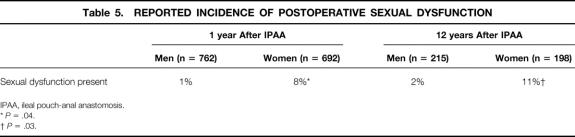

Pouch Failure

The cumulative probability of developing pouch failure after IPAA for CUC based on patient age is shown in Figure 3; the probability based on patient sex is shown in Figure 4. Reasons for pouch failure are shown in Table 3. Pelvic sepsis and its primary sequela, pouch fistula, were the most common causes of pouch failure. The poorer functional outcomes in older patients did not translate into a higher late risk of pouch failure, however. Sex was not a significant risk factor for the development of pouch failure.

Figure 3. Probability of success: older patients versus younger patients.

Figure 4. Probability of success: men versus women.

Table 3. REASONS FOR POUCH FAILURE

There were no differences between groups.

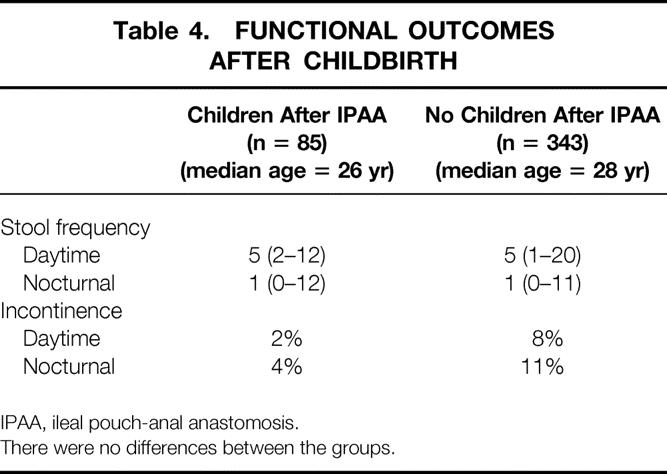

Impact of Childbirth on Pouch Function

Among the 692 women, data regarding pregnancy after IPAA was available for 546. Of these, 85 had a pregnancy and vaginal delivery after IPAA. The median age at surgery of women who did not have children after IPAA was 33 (range 11–63) years compared with 26 (range 5–39) years for women who did have children (P < .0001). Functional outcomes were compared between the 85 women who became pregnant and 343 women younger than 40 years of age at the time of IPAA who did not have children (Table 4). Functional outcomes were similar between these two groups, and childbirth did not appear to have a deleterious impact on subsequent pouch function.

Table 4. FUNCTIONAL OUTCOMES AFTER CHILDBIRTH

IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

There were no differences between the groups.

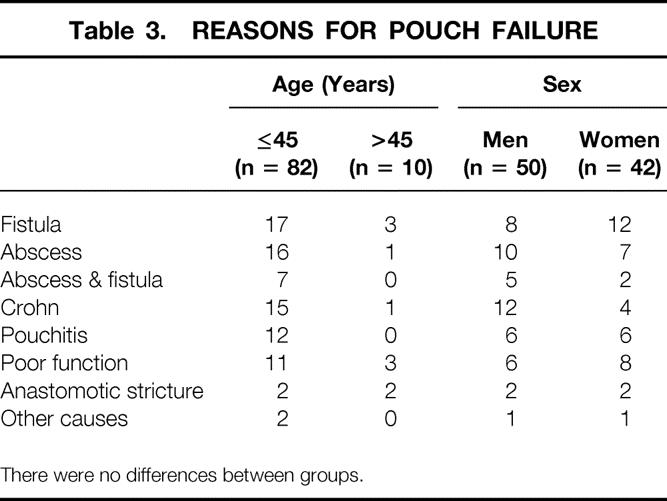

Sexual Dysfunction

Before surgery, 16% of patients reported complete abstinence from sexual activity and 20% had reduced sexual activity. After IPAA, 25% reported an improvement in the quality of their sexual life, 56% believed that surgery had not affected this aspect of their personal life, 16% indicated that sexual activities were mildly restricted, and 3% reported severe restrictions. Ten years after IPAA, retrograde or no ejaculation was reported by 3% of men. Among women, dyspareunia affected 8% early and 11% late, whereas fecal leakage during intercourse affected 3% (Table 5).

Table 5. REPORTED INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.

*P = .04.

†P = .03.

DISCUSSION

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is an established surgical option for the treatment of CUC principally because the complication rate is reasonable, a stoma is avoided, fecal continence is preserved, and long-term outcomes are good. 1–3,10 The use of an annual postoperative patient questionnaire, which is independent of the surgeon’s influence, has previously been reported from this institution 1 and allows long-term assessment of outcomes after IPAA in a standardized manner. This methodology has been recommended as a way to obtain realistic postoperative long-term assessment of large numbers of patients in the community. 2

Perioperative anal physiology was not routinely performed to predict postoperative function because it cannot consistently predict postoperative outcomes. 11 Change in pelvic floor and anal sphincter physiology have nevertheless been demonstrated in older patients, attributed to the aging process. 4,5,12 Little is known about the impact of this aging process on long-term functional outcomes after IPAA. In this study, patients who were younger than 45 years at the time of surgery had increased frequency of spotting as they grew older, but incontinence remained uncommon. The need for perineal pads and for constipating/stool-bulking medication did not change with longer follow-up.

We 1 and others 7,9 have consistently found older patients (older than 50 years) to have a marginally worse functional outcome on short-term follow-up after IPAA. Other problems, however, including pouchitis, perianastomotic stricture, and overall failure, did not occur more frequently in older patients. Transient impairment of internal anal sphincter function after IPAA 13 has been described and is considered to affect patients older than 50 more severely than younger patients. 14 We found that older patients had a higher frequency of nocturnal stool and more episodes of fecal incontinence compared with younger patients. These observations became more pronounced in patients with more than 12 years of follow-up after IPAA. (Although functional outcomes were poorer in older patients, pouch failure directly attributable to incontinence and poor anal function was uncommon.)

Functional outcomes were comparable between men and women. The impact of childbirth on continence may be considerable: several authors have reported that up to 30% of women in the general population undergoing vaginal delivery have an occult anal sphincter injury. 15,16 Pelvic floor denervation may also accompany childbirth and may contribute to incontinence at an older age. 17 Previous reports from the Mayo Clinic found that functional outcome after childbirth in women after IPAA was not compromised. 18 The present study confirms these earlier reports in a larger number of women with longer follow-up. A more complete understanding of delivery-related complications and functional outcomes awaits analysis.

Perioperative occlusion of the fallopian tubes has previously been described and was thought to contribute to postoperative subfertility after IPAA. 19 Eighty-five of 428 women younger than 40 in this study conceived after IPAA, but the intent to conceive was not prospectively assessed in this study. Proctocolectomy and restoration of well-being has been associated with improved sexual function. 20,21 Half of the patients in this study reported no change in libido after surgery, and a quarter reported some improvement. Of the 19% who reported some postoperative restriction of sexual activity, most were women, and this may merit preoperative counseling. 22 Pelvic pain and fear of soiling during intercourse were the primary concerns. These symptoms have previously been attributed to postoperative deformation of the adnexa 23,24 and alterations in the nature of vaginal secretions. 20,22 We documented previously that the incidence of sexual dysfunction in women was the same whether or not they had experienced pelvic sepsis. 25

Pelvic sepsis alone or with pouch fistula was the primary cause of pouch failure, irrespective of patient age or sex. Sepsis accounted for 45% of all pouch failures within 2 years after IPAA but for less than 2% of all subsequent failures. Overall patterns of late pouch failure were similar to those reported by others. 3,10 Subsequent diagnosis of small bowel Crohn disease was the primary cause of late failure in younger patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Stool frequency and continence are similar between men and women after IPAA for CUC. Childbirth is feasible after IPAA and does not result in subsequent poor pouch function. The aging process has not as yet resulted in an increase in the number of pouch failures from poor function. Older patients generally have more frequent pouch evacuations, and incontinence is more common. Pelvic sepsis, pouch fistulas, and Crohn disease are the primary causes of pouch failure irrespective of patient age or sex. The cumulative risk of pouch failure is similar between younger and older patients but remains gratifyingly low.

Discussion

Dr. Harvey J. Sugerman (Richmond, Virginia): This is another impressive large series of ileoanal pouch procedures from the Mayo Clinic. With this large volume of patients, they have been able to show that the operation is very effective on long-term follow-up. Of special interest, they noted that women who become pregnant can safely deliver their baby vaginally without damage to the function of their ileoanal pouch. Was this universally true? Did no patient develop pouch dysfunction after vaginal delivery?

The authors also did not present data regarding the percent of women who could not become pregnant after the pouch procedure. We have had several patients from our earlier experience with a handsewn mucosectomy procedure who have required complicated and expensive in vitro fertilization procedures because of infertility.

We also noted an increased risk of incontinence in our older patients, yet they still state that they would prefer their ileoanal pouch to an ileostomy. You found no difference in pouch failure rate between your patients older than 45 versus the younger group. According to this report, the Mayo Clinic does not offer this operation to patients older than 65. We have performed a one-stage triple-stapled ileoanal pouch procedure without temporary ileostomy in 194 patients, of whom 16 were 60 years or older, 8 were older than 66, and 3 older than 70, with excellent results.

The data presented admit that 53% of the patients need to wear a perineal pad at 1 year and 55% at 12 years after a mucosectomy and handsewn ileoanal pouch procedure in patients over 45, and 28% and 22% need to wear a pad in patients younger than 46 because of problems with incontinence, especially at night. Less than 10% of our patients with a triple-stapled ileoanal pouch procedure admit to nocturnal incontinence episodes in the absence of pouchitis symptoms, or the need to wear a perineal pad. Your previous randomized prospective study with a limited number of patients confirmed our data of an increased resting anal sphincter pressure after a stapled versus mucosectomy and handsewn pouch procedure, and the data had a trend toward improved continence with the stapled approach. I was concerned that the lack of significance in your study was secondary to both a type II statistical error, that is, it might have become significant had you entered more patients into the study. And furthermore, I wondered that the patients with the stapled procedure may have had pouchitis that would have caused incontinence, but the presence of pouchitis might not have been detected with the questionnaire-type survey used by the Mayo Clinic.

The authors list several criteria for the diagnosis of pouchitis in their manuscript, but they exclude the two symptoms that we believe to be most important: new onset of watery diarrhea without bleeding and problems with urgency and incontinence. So I wondered if your incidence and frequency of recurrent pouchitis might actually be higher than 4% on a recurrent basis. It certainly seems to be in most other series, including ours.

Approximately 7% of the patients not lost to follow-up developed pouch failure. With the triple-stapled procedure, our pouch failure rate is 3%, one half due to unsuspected Crohn’s disease at the original operation, and one half due to intractable pouchitis.

Therefore, my other questions are:

One, why don’t you offer this operation to patients older than 65?

Two, do you offer this procedure to severely obese patients, that is, those with a body mass index greater than 30?

Three, was there a significant difference in your stapled versus mucosectomy handsewn patients in this study in terms of incontinence or other functional aspects?

Four, are you doing the one-stage procedure in patients who have the stapled operation without a temporary ileostomy?

Five, are you missing patients with pouchitis with your rather rigid definition of the problem?

And, lastly, have you ever intentionally offered this operation to a patient with Crohn’s disease confined to the large intestine, after providing informed consent to the patient that there still will be a 50% pouch failure rate?

Dr. Edward M. Copeland III (Gainesville, Florida): Dr. Farouk, in your pie chart all the pouchitis patients were in the less-than-45-years-old age group. Why was there no pouchitis in the older age group?

Dr. Ridzuan Farouk (Closing Discussion): I thank Dr. Sugerman and Dr. Copeland for their very incisive questions. In relation to the safety of vaginal delivery, we reviewed the series of women who had pouch failure and none of them had undergone childbirth postoperatively. Interestingly, if we compared the women who had complications during childbirth to those women who had children but had no complications, the incidence of incontinence, the need to use constipating medication, and the need to use a protective perineal pad are exactly the same. Additionally, when we looked at the women who did not have children after pouch surgery and compared them to the women who did, the requirement for constipating medication in both groups of women went down after 1 year. So as far as we can tell, there is no detrimental impact of vaginal delivery on pouch function.

In relation to fertility, it is often difficult to separate the woods from the trees. We did not look specifically at fertility problems preoperatively or postoperatively in terms of the intent to become pregnant, but we agree with you that that is an important point. My training is British, but I am told that the incidence of subfertility in American women is approximately 30%, and it is, I think, difficult to separate those who are infertile because of their pouch surgery from those who are infertile for other reasons. This needs to be looked at prospectively.

In relation to age, we do not disagree in the least with the operation being performed in older patients. We offer the patient a pouch based on their physiologic age rather than their chronologic age. But we think you would agree, based on the data that you presented in your question, that these patients are really few and far between. Additionally, we have some concern in terms of offering this operation to elderly women, who we feel are particularly compromised in terms of anal sphincter function.

In relation to the double-stapled procedure compared to a mucosectomy, we acknowledge your significant contribution in this area in terms of this debate. There have been four prospective trials showing no difference between stapled and mucosectomy patients. We agree with you that the number of patients in those trials was small; however, metaanalysis of 180 patients from the four series showed there was no difference in outcomes comparing mucosectomy patients and double-stapled patients. Additionally, results from the Cleveland Clinic Florida comparing younger and older patients at 2 years after stapled IPAA, are exactly the same as our patients’ results at 10 years after mucosectomy. Eighty-five percent of patients have either good or satisfactory outcomes, irrespective of whether they have a double-stapled or mucosectomy procedure.

We agree that the diagnosis is difficult to make accurately. Specifically, in specific relation to the question as to patients who have diarrhea without bleeding and/or sudden onset of urgency and incontinence, this is probably irritable bowel rather than pouchitis. Denis Nyam from our institution presented data to the AGA about 3 years ago regarding IBS and IPAA. He looked at patients preoperatively and postoperatively and found that 25% of patients with symptoms of IBS prior to pouch surgery still had symptoms of IBS after pouch surgery. Given that 25% to 30% of people in the general population have IBS, it is likely that some patients with CUC also have IBS, and therefore, we feel these patients fall into that category.

In relation to your pouch failure rate, this is a very impressive 3%. Last year, I looked at the pouch failure at Mayo in relation to pelvic sepsis, and found that the pouch failure rate at Mayo in the last 10 years is only 2%. The higher figure presented today relates to the relatively high pouch failure rate that was experienced in the first 5 years of this operation at Mayo.

In summary, we do offer the patient the pouch operation irrespective of age, providing patients are fit. Secondly, in terms of obese patients, we have operated on people with a very high BMI. We do not, however, specifically know what their results are in relation to people who are thinner.

Do any of the attending surgeons at Mayo currently double-staple? The answer is yes, but the operation is still performed nearly always in two stages.

Have we intentionally offered this operation to a patient with Crohn’s disease? The short answer is no. There is a randomized trial being formulated at Mayo at the moment to offer this type of surgery to patients with Crohn’s disease within a prospective trial.

In answer to Dr. Copeland’s question about pouchitis, it is very interesting: we don’t know why older patients seems to have fewer episodes of pouchitis. The other interesting thing is that pouch failure did not occur in older patients after 5 years’ follow-up, whereas there was still a continuing drop in the number of successful pouches over a longer period of time in the younger patients. We don’t know why that is, but most younger patients who have pouch failure over a long period of time have pouch failure because of Crohn’s disease; this does not seem to happen in older patients. We don’t know why pouchitis is not that common in older patients.

Footnotes

Correspondence: John H. Pemberton, MD, Mayo Clinic, E6A, 200 First St. SW, Rochester MN 55905.

Presented at the 111th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 5–8, 1999, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

E-mail: pemberton.john@mayo.edu

Accepted for publication December 1999.

References

- 1.Pemberton JH, Kelly KA, Beart RW, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Long-term results. Ann Surg 1987; 206:504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michelassi F, Stella M, Block GE. Prospective assessment of functional results after ileal J pouch-anal restorative proctocolectomy. Arch Surg 1993; 128:889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church J, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg 1995; 222:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannister JJ, Abouzekry L, Read NW. Effect of aging on anorectal function. Gut 1987; 29:353–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauberg S, Swash M. Effects of aging on the anorectal sphincters and their innervation. Dis Colon Rectum 1989; 32:737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stonnington CM, Phillips SF, Melton LJ III, Zinsmeister AR. Chronic ulcerative colitis: incidence and prevalence in a community. Gut 1987; 28:402–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis WG, Sagar PM, Holdsworth PJ, et al. Restorative proctocolectomy with end-to-end anastomosis in patients over the age of fifty. Gut 1993; 34:948–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keighley MRB. The role of pouch-anal anastomosis in the elderly. Perspectives Colon Rectal Surg 1996; 7:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reissman P, Teoh TA, Weiss EG, et al. Functional outcome of the double-stapled ileoanal reservoir in patients more than 60 years of age. Am Surg 1996; 62:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ, et al. Long-term results of the ileoanal pouch procedure. Arch Surg 1993; 128:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church JM, Saad R, Schroeder T, et al. Predicting the functional result of anastomoses to the anus: the paradox of preoperative anal resting anal pressure. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36:895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHugh SM, Diamant NE. Effect of age, gender and parity on anal canal pressures: contribution of impaired anal sphincter function to faecal incontinence. Dig Dis Sci 1987; 29:353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farouk R, Duthie GS, Bartolo DCC. Recovery of the internal anal sphincter after restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg 1994; 81:1065–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorge JMN, Wexner SD, James K, et al. Recovery of anal sphincter function after the ileoanal reservoir procedure in patients over the age of 50 years. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37:1002–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burrnett SJ, Spencer-Jones C, Speakman CT, et al. Unsuspected sphincter damage following childbirth revealed by anal endosonography. Br J Radiol 1991; 64:225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, et al. Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:1905–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snooks SJ, Swash M, Mathers SE, Henry MM. Effect of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor: five-year follow-up. Br J Surg 1990; 77:1358–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juhasz EJ, Fozard B, Dozois RR, Ilstrup DM. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis function following childbirth: an extended evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asztely M, Palmblad S, Wikland M, Hulten L. Radiological study of changes in the pelvis in women following proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 1991; 6:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scaglia M, Bronsino E, Canino V, Hulten L. The impact of conventional proctocolectomy on sexual function. Minerva Chir 1993; 48:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metcalf AM, Dozois RR, Kelly KA. Sexual function in women after proctocolectomy. Ann Surg 1986; 204:624–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ambrick M, Fazio VW, Hull TL, Pucel G. Sexual function after restorative proctocolectomy in women. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oresland T, Palmblad S, Ellstrom, et al. Gynaecological and sexual function related to anatomical changes in the female pelvis after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 1994; 9:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wikland M, Jansson I, Asztely M, et al. Gynaecological problems related to anatomical changes after conventional proctocolectomy and ileostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 1990; 5:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farouk R, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH. Incidence and subsequent impact of pelvic abscess after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41:1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]