Abstract

Objective

To compare the impact of staging systems on the survival of 1,038 patients with gastric cancer undergoing resection for cure in a North American center.

Summary Background Data

In 1997, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer redefined N stage in gastric cancer. The number of involved nodes rather than their location defines N, and a minimum of 15 examined lymph nodes is recommended for adequate staging. In the 1988 AJCC N-staging system, N1 and N2 node metastases were defined as within 3 cm or more than 3 cm of the primary; the 1997 AJCC N stages were defined as N1 = 1 to 6 positive nodes, N2 = 7 to 15 positive nodes, and N3 = more than 15 positive nodes.

Methods

Between 1985 and 1999, 1,038 patients underwent an R0 resection. Median and 5-year survival rates were compared and the Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate median survival.

Results

The location of positive nodes did not significantly affect median survival when analyzed by the number of positive nodes. In contrast, the number of positive lymph nodes had a profound influence on survival. The new N categories served as a better discriminator of median survival when 15 or more nodes were examined. Survival estimates for stages II, IIIA, and IIIB were significantly influenced by examining 15 or more nodes.

Conclusion

The number of positive nodes best defines the prognostic influence of metastatic lymph nodes in gastric cancer. Survival estimates based on the number of involved nodes are better represented when at least 15 nodes are examined.

The need for a simple, accurate, and reproducible system of staging is of paramount importance when comparing and evaluating results. The TNM system, first published largely as a clinical classification by the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) in 1966, has been modified to meet this end. 1 In 1970, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) applied the TNM system using histopathologic data for the staging of stomach cancer. 2 Although the three main staging systems for this disease (UICC, AJCC, and Japanese Committee on Cancer) differed in some respects from the TNM classification, the UICC and AJCC reached complete agreement in their definitions of TNM and stage groupings as of 1982. The Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC), although more detailed, was until recently similar to the UICC/AJCC classification. 3

In the past, all staging systems used for this disease defined N stage by the location of lymph node metastases relative to the primary. Metastatic lymph nodes within 3 cm of the primary were considered N1; lymph node metastases more than 3 cm from the primary were N2. However, in North America, compliance with this staging system has been low, so results cannot be meaningfully compared with those from centers in Japan, other Asian countries, and specialist centers in Europe. In 1997, the UICC and AJCC 4,5 redefined the pathologic nodal status based on the number of involved nodes rather than their location. In an effort to improve staging accuracy, it was recommended that a minimum of 15 lymph nodes be examined to define N0. In this study, we compare the impact of this change on the survival rates of 1,038 patients with gastric cancer undergoing resection for cure in a North American center.

METHODS

Between July 1, 1985, and June 30, 1999, 2,286 patients were admitted to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center with a diagnosis of gastric cancer and were entered into the Department of Surgery’s prospective database. Of the 2,041 admitted for treatment of primary disease, 1,038 patients underwent an R0 resection (defined by the UICC 6 and AJCC 4 as no residual gross or microscopic tumor) and were included in this study. 1 The operating surgeon indicated the extent of lymphadenectomy. Seventy-five percent of patients undergoing resection had a D2 or greater lymphadenectomy, with lymph node stations 1 to 11 removed in accordance with the rules of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. 7

TNM Classification

Because there is no difference between the UICC and AJCC TNM classification, we will refer to this as the AJCC for brevity. N stage was defined according to the 1988 AJCC staging system (nodal metastases within 3 cm of the primary were N1; lymph node metastases greater than 3 cm from the primary were N2) or by the 1997 AJCC stage (N1 = 1–6 positive nodes; N2 = 7–15 positive nodes; N3 = >15 positive nodes). The 1997 classification requires that a minimum of 15 lymph nodes be examined to determine whether a patient is N0.

Survival

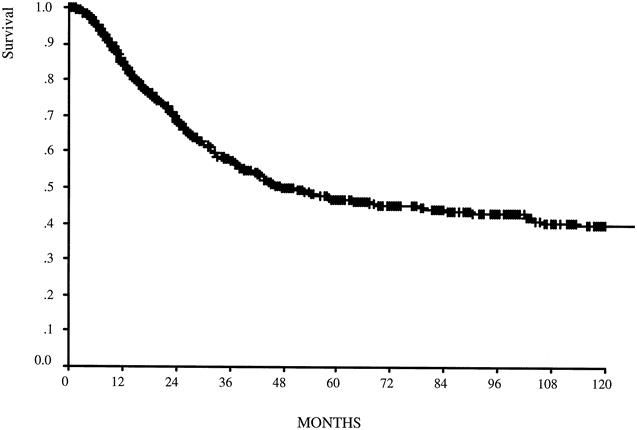

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival. 8 Differences in survival were determined by the log-rank test. The event used was death of disease such that all survival curves represent disease-specific survival. All other events were treated as censored. Follow-up status was entered as death of disease (n = 416; 40.1%), death of other causes (n = 137; 13.2%), alive with disease (n = 51; 4.9%), or no evidence of disease (n = 434; 41.8%).

The median follow-up from the date of surgery was 23.0 months (range 0.23–164) for all patients and 36 months (range 0.29–164) for survivors. Follow-up status was available for all patients.

Cox regression was used to analyze multiple variables and determine relative risk. 9 The SPSS for Windows Release 9.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) statistical package was used to generate these analyses. In the multivariate analysis, 22 patients with site = whole stomach, 16 patients with T stage Tis, 45 patients with unknown type of lymphadenectomy, and 7 patients with missing N stage (1997) status were omitted. The number of patients entered into the final regression model was 995. Differences in the distribution of variables were determined by the chi-square test.

RESULTS

Clinicopathologic Data

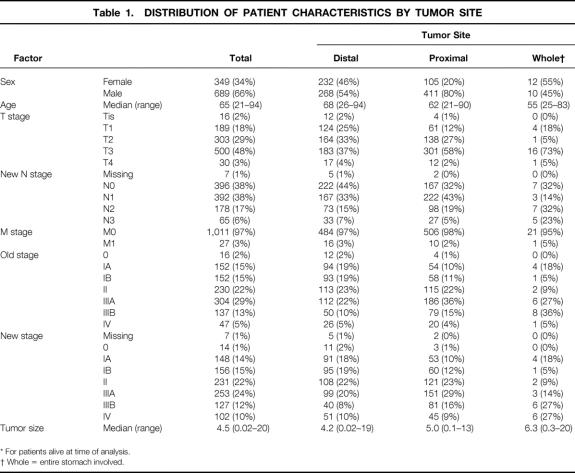

Patient and pathologic characteristics for all 1,038 patients are shown in Table 1 by tumor site. The gender ratio was 2:1 for men, with men making up a significant percentage of those with proximal tumors. The median age was 65 (range 21–94). Eighty-three percent of patients were white, 7% Asian, 6% Hispanic, and 4% black.

Table 1. DISTRIBUTION OF PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS BY TUMOR SITE

* For patients alive at time of analysis.

† Whole = entire stomach involved.

T Stage

More than half the patients had T3 or greater tumors (51%). The percentage increased to 60% for proximal tumors and 78% for tumors involving the whole stomach. Tumor site was as follows: antrum, n = 276; body, n = 224; proximal third, n = 161; and gastroesophageal junction, n = 335. Median tumor size was 4.5 cm (range 0.02–20.0) for the 1,003 patients in whom measurements were available.

N Stage

The median number of lymph nodes examined was 21 (mean 23.9). Overall, 635 (61.8%) of patients had lymph node metastases. Of these patients, the median number of involved nodes was 4.0 (mean 6.87). It is assumed in the 1997 TNM classification that 15 or more nodes will be examined. Twenty-seven percent of patients in this study did not meet this criterion. Seven patients did not have a specified number of lymph node metastases.

M Stage

Three percent of patients had M1 tumors on the basis of distant nodal metastases according to the 1988 TNM definition. This increased to 6% using the 1997 TNM definition.

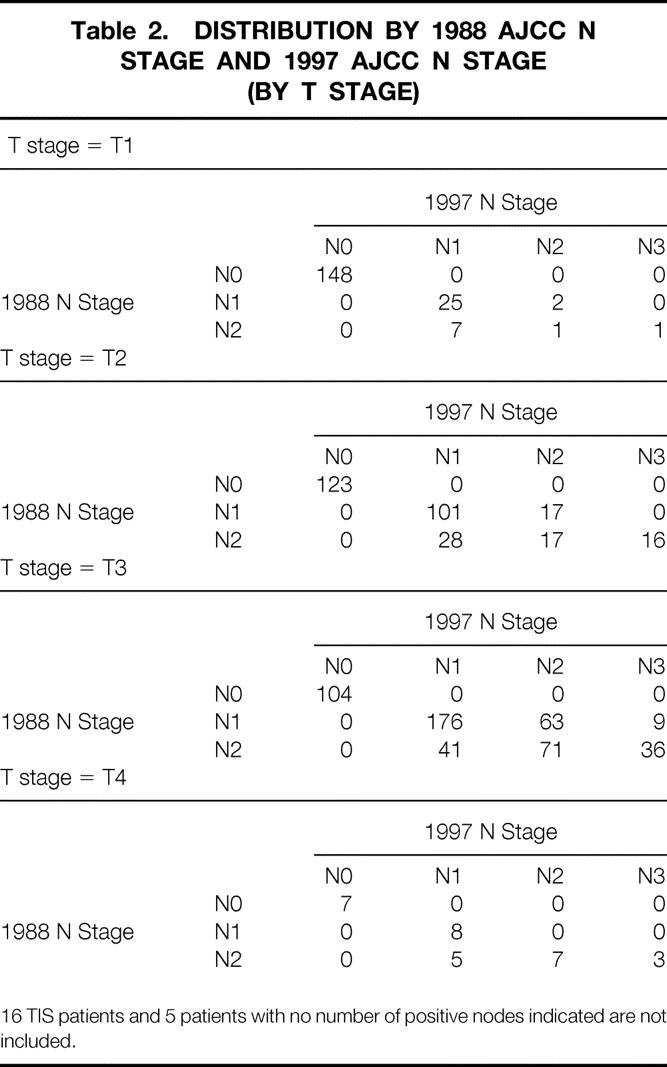

Patient Distribution by N Stage

The N-stage distribution by T stage for both the 1988 and 1997 TNM classifications is shown in Table 2. The number of patients whose N stage changed when reclassifying from the old AJCC N stage (site) to the new one (number) was 91 (22.6%) for N1 and 137 (58.7%) for N2. The biggest change in N classification was seen in the T3 tumors. The distribution of patients for each TNM stage did not change significantly when defined by the 1988 or 1997 N-stage classification (see Table 1).

Table 2. DISTRIBUTION BY 1988 AJCC N STAGE AND 1997 AJCC N STAGE (BY T STAGE)

16 TIS patients and 5 patients with no number of positive nodes indicated are not included.

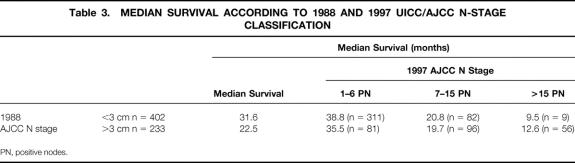

Survival by N Stage

The median survival and the 5-year survival rate of patients staged by the 1988 N stage were 31.6 months and 31% for N1 and 22.5 months and 20% for N2. The new N stage further divided the 402 N1 patients and 233 N2 patients into three groups, with significantly different median survivals (Table 3). In contrast, the location of positive nodes (≤3 cm or >3 cm from the primary) had no impact on median survival when determined by the number of positive nodes.

Table 3. MEDIAN SURVIVAL ACCORDING TO 1988 AND 1997 UICC/AJCC N-STAGE CLASSIFICATION

PN, positive nodes.

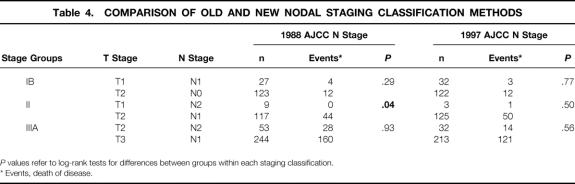

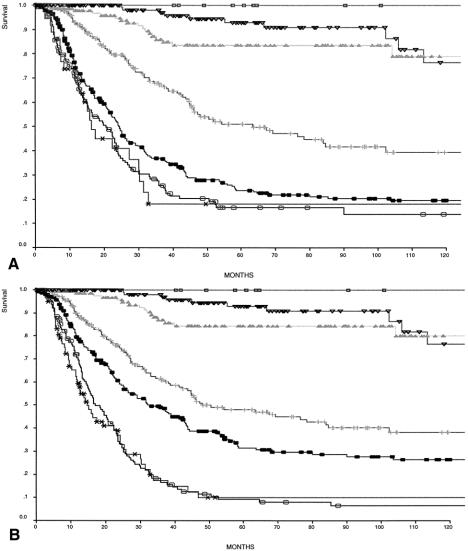

Survival By TNM Stage

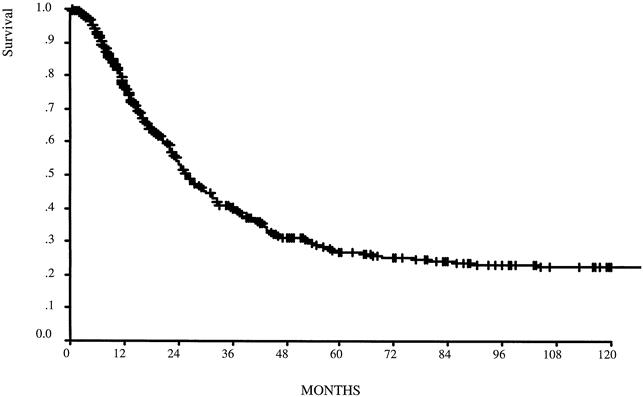

The 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 49% for the 1,038 patients overall and 27% for the 635 node-positive patients (Figs. 1, 2). In Table 4, comparisons of survival by TNM for stages IB, II, and IIIA show a more homogeneous relationship in each stage group when defined by the 1997 TNM classification. Five- and 10-year survival rates are shown for TNM stage as defined by the two classification systems (Fig. 3). Both classifications significantly stratify survival but differ for stage III patients. The Kaplan-Meier curves for stages IIIA and IIIB are clearly better separated when the number of lymph node metastases defines pN.

Figure 1. Disease-specific survival for the entire group (n = 1,038). Median follow-up was 23 months for the entire group and 36 months for survivors.

Figure 2. Disease-specific survival for the node-positive group (n = 635). Median follow-up was 17 months for the entire group and 28.5 months for survivors.

Table 4. COMPARISON OF OLD AND NEW NODAL STAGING CLASSIFICATION METHODS

P values refer to log-rank tests for differences between groups within each staging classification.

* Events, death of disease.

Figure 3. Comparison of disease-specific survival by (A) 1988 staging (N defined by the site of lymph node metastases) and (B) 1997 staging system (N defined as the number of involved nodes). □, Stage 0; ▿, Stage IA; ▴, Stage IB; +, Stage II; ○, Stage IIIA; •, Stage IIIB; ∗, Stage IV.

Influence of Number of Examined Nodes on Staging

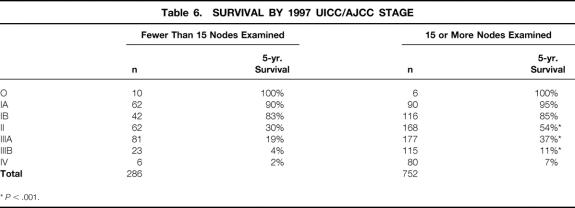

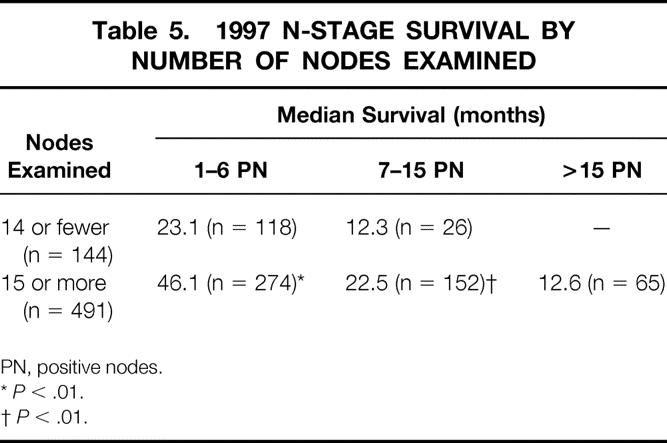

Applying all aspects of the 1997 AJCC TNM classification requires that the number of lymph nodes examined be at least 15. Two hundred eighty-six (27%) of our patients had fewer than 15 nodes examined. We sought to determine what impact, if any, this had on the quality of staging. The overall distribution of patients staged by the 1997 AJCC classification did not change significantly if 15 or more lymph nodes were examined, but median survival for N1, N2, and N3 by the 1997 classification increased significantly when 15 or more lymph nodes were examined (Table 5). AJCC staging-based survival estimates were significantly influenced in stages II, IIIA, and IIIB when determined by the 1997 AJCC staging (Table 6).

Table 5. 1997 N-STAGE SURVIVAL BY NUMBER OF NODES EXAMINED

PN, positive nodes.

*P < .01.

†P < .01.

Table 6. SURVIVAL BY 1997 UICC/AJCC STAGE

*P < .001.

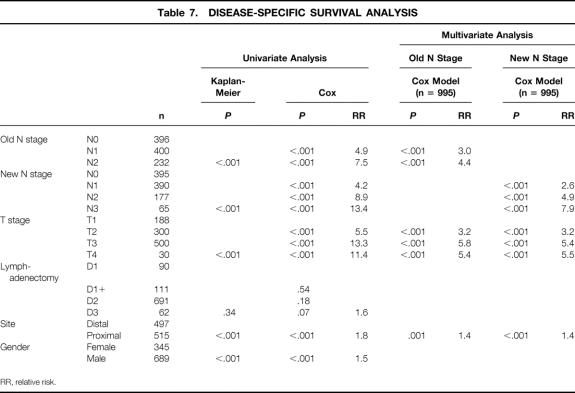

Multivariate Analysis

Univariate analyses were performed for pT stage, pN stage (1988 and 1997 definitions), tumor site, gender, and extent of lymphadenectomy. All but lymphadenectomy were found to be significant factors. Significant factors were then entered into a Cox regression analysis (Table 7). Depth of tumor invasion, N stage (1988 and 1997), and tumor site were all independent predictors of survival. The relative risk determination for any one factor was not significantly influenced by which definition of pN was entered into the Cox model.

Table 7. DISEASE-SPECIFIC SURVIVAL ANALYSIS

RR, relative risk.

DISCUSSION

The AJCC formally adopted the TNM classification of gastric cancer in 1970. A task force made up of seven institutions from North America and Hawaii demonstrated that the depth of tumor invasion (T), the location of perigastric lymph node metastases (N), and the presence or absence of distant metastases (M) significantly predicted outcome in 1,241 patients with resected gastric cancer. 2 The definitions of T and M have remained fairly consistent, but universal acceptance of the TNM system has been stifled, primarily by disagreement over the definition of N stage. The Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer defined perigastric and regional lymph nodes by a numbering system (1 to 16) first published in 1962 in the General Rules for Gastric Cancer Study. These rules, based on careful documentation of stomach cancer progression, have not been widely applied in North America 9 and were first published in English in 1995. 3 An attempt to simplify the Japanese system by Japanese surgeons has not caught on in Japan. 10 In 1982, the UICC and AJCC agreed to define pN1 as 3 cm or less from the primary and pN2 as greater than 3 cm from the primary or nodal metastases along named blood vessels, in keeping with the JCGC. It was proposed in 1995 during the first International Gastric Cancer Congress in Kyoto that pN stage be defined by the number of metastatic lymph nodes to achieve a single uniform staging system.

The 1997 revision of the UICC 5 and AJCC 4 TNM classification changed the definition of N stage to reflect the number of involved nodes: N1 has 1 to 6 metastatic regional nodes, N2 7 to 15, and N3 more than 15. In the present study, we compare the accuracy of this new TNM staging system on a large cohort of North American gastric cancer patients treated at a single institution.

Six hundred thirty-five of our patients had lymph node metastases (61%). This is higher than some have reported 11,12 and probably reflects the greater percentage of tumors located in the proximal and whole stomach (51.8%), which are more likely to be node-positive.

We found that the new 1997 TNM system resulted in better homogeneity of survival than the old 1988 system. Of the 402 patients classified as N1 by the 1988 TNM, 23% were upstaged to either N2 (n = 82; 7–15 positive nodes) or N3 (n = 9; >15 positive nodes) by the new system. Of the 233 patients in the 1988 N2 group, 59% were changed to either N1 (n = 81; 1–6 positive nodes) or N3 (n = 56; >15 positive nodes). Median survival of the 402 1988 N1 patients was subdivided into three significantly distinct groups when redefined according to the 1997 N stage. Similar findings have been reported from Germany 12 and Japan, 13–15 where the new 1997 N classification was clearly superior to either the UICC/AJCC 1992 N or JCGC N systems, which both rely on the location of lymph node metastases.

Combining T and N to form the AJCC stage had remarkably little effect on the stage distribution of our patients, regardless of which classification system was used. Differences between the two systems became apparent only when survival was analyzed for the later stages. Stage IIIA 5-year survival rates increased with the new 1997 AJCC staging system compared with the 1988 system from 23.7% to 31.7%. Stage IIIB decreased from 16.7% to 9%, resulting in a better stratification of stage III survival by the new system.

Five- and 10-year survival rates were essentially unchanged between the two systems for stages IA to II, although within stage II, the rate of death from disease was significantly higher for T2N0 patients than for T1N2 patients when N was defined by the 1988 TNM definition. This difference was not apparent when the 1997 TNM stage was applied, resulting in better homogeneity between the stage II TNM subgroups.

Several centers have begun to apply and compare the 1997 staging system with earlier versions of the AJCC, UICC, and JCGC classifications. 11,12–16 Roder et al 12 published a careful analysis of 477 node-positive patients treated in the German Gastric Cancer Study and found that N-stage survival, when defined by the number of nodes, was not altered when the location of the nodes was considered. Hayashi et al 11 compared the new 1997 UICC TNM staging system with the 1993 Japanese system, which classifies N into four groups by site. They found, as we did, that survival as determined by the location of perigastric nodes was further stratified into three distinct groups by the number of positive nodes. Kodera et al 16 also applied the 1997 TNM classification to 493 Japanese patients who had all undergone D2 or D3 resections, and they concluded that the number of nodes was a strong prognostic indicator that should replace the N categories in the JCGC. The number of studies concluding that N staging based on the number of positive nodes is superior to N staging based on number is growing.

The prognostic significance of assessing the number of involved nodes has been appreciated for some time. 17–21 Because the positive-node number is a continuous variable, defining significant prognostic cutoff points varies from one center to the next, given the unique characteristics of the patient population. Shiu et al 22 found that more than three positive nodes significantly lowered median survival and independently predicted a poor outcome after curative resection. We recently also found that survival decreases significantly when more than three positive nodes are involved (data not shown). Jatzko et al 23 suggested one to three as a cutoff for N1, four to six for N2, and more than six for N3. Lee et al 24 determined that more than 4 was a significant cutpoint and recommended that 1 to 3 positive nodes designate N1, 4 to 10 for N2, and more than 10 for N3. Using two-sample log-rank test statistics to identify the optimal cutpoint values for the number of involved regional lymph nodes, Roder et al 12 found the three homogeneous subgroups that currently define the UICC/AJCC N-stage definition. Our findings support the strong prognostic value of using 1 to 6 positive nodes as N1, 7 to 15 as N2, and greater than 15 as N3.

The quality of N staging, from the standpoint of both surgical technique and handling of the specimen by the pathologist, has varied. Counting the number of positive nodes seems less complex and straightforward, but compliance with the rules of the 1997 UICC/AJCC TNM classification will still require major changes. Several Western centers do not report the number of positive lymph nodes, and many fall short of the new minimum lymph node requirement. In fact, 23% of our patients had fewer than the required 15 nodes examined, although many of them had undergone resection before 1991.

The impact of examining 15 nodes or more lymph nodes on the 1997 AJCC stage was striking. Survival significantly increased for stages II, IIIA, and IIIB. The stage IIIA survival rate increased from 19% to 31.4% when grouped by the number of lymph nodes examined; stage IIIB increased from 4% to 11%. Because 36% of patients in the study were stage IIIA or IIIB, changes in survival of this magnitude will significantly influence the interpretation of treatment results. This probably indicates stage migration, because 52% of those with 14 or fewer examined nodes had a D2 or greater lymphadenectomy, and another 17% had a D1 plus parts of a D2 dissection. Bunt et al 25 emphasized that the extent of lymph node dissection and the thoroughness of the pathologist’s examination of the specimen together determine the number of lymph nodes ultimately retrieved. It is clear that techniques such as fat clearing 26 can increase the number of nodes and that an increase in the number of nodes will increase the number of positive nodes, which will alter stage. Kodera et al 16 tried to illustrate the effect of performing less than a D2 lymphadenectomy on the new TNM classification by applying the new classification to JCGC level 1 nodes retrieved after a D2 or D3 lymphadenectomy, disregarding information from level 2 nodes. Five-year survival rates deteriorated for all three N stages. The 13 patients classified as N0 had skip metastases to level 2 that would have been missed had a D1 dissection been done, indicating the influence of stage migration. Because any survival benefit afforded by the D2 lymphadenectomy was offset by the increase in surgical deaths, it is unlikely that surgeons currently performing a D1 lymphadenectomy are going to change. Establishing a minimum number of nodes to examine begins to address this issue.

The overall survival rate for this group of patients was 47% at 5 years. The survival based on the 1997 TNM classification resulted in survival results that more closely approximate those reported from Japan and specialty centers in Europe. Multivariate analysis confirmed that after an R0 resection, T and N stage and the site of the tumor are powerful independent predictors of survival.

In conclusion, the 1997 pN stage definition is a more homogeneous and more widely applicable classification of AJCC stage than past classifications. The number of involved nodes more accurately reflects the burden of disease and should be more reproducible, provided that the number of examined nodes is standardized. North American centers should endeavor to ensure that all patients undergoing an R0 resection for gastric cancer should undergo histopathologic examination of at least 15 lymph nodes. Accurate staging can then be achieved and comparative analysis of outcomes should be possible.

Discussion

Dr. J. Rudiger Siewert (Munich, Germany): This is a very careful analysis of the prognostic impact of the lymph node metastases. I think such type of analysis is absolutely necessary to realize that the new UICC classification is better than the older one.

You have to realize that the TNM classification is a strict prognostic classification and should be used worldwide. Such a classification must be simple, easy to perform, and reproducible. You can draw no observational consequences from the TNM classification, in contrast to the Japanese classification, which tends to give information about the anatomical extent of lymph node metastases. The problem is that if you want to have an anatomical classification, the surgeon has to do this classification like in Japan. In the Western hemisphere, we have the feeling that the pathologists have to do it, and this is something like a quality control of the surgery. Then the numerical classification is much more appropriate. It is good to see that this new TNM classification gives better prognostic information also in the United States.

May I ask you some small questions? First, the information regarding the number of involved lymph nodes is coming from the pathological analysis. So our analysis has an important impact on this classification. Can you tell us a little bit more in detail how your pathologist is separating the lymph nodes from the specimen and how he is counting the lymph nodes? Is he doing this microscopically or macroscopically? What is the way to do it?

The second question: As you have stressed, the requested number of 15 lymph nodes as a precondition for the new classification is also a contribution to the quality of surgery and control of lymphadenectomy possible. You have stressed the survival benefit. Do you have any information how many patients are resected adequately—they have a resection of >15 lymph nodes—in the United States?

Last but not least, the most independent and important prognostic factor is the lymph node ratio. That means the ratio between the number of excised and the number of involved lymph nodes. A lymph node ratio below .2 indicates a good prognosis. Do you have any information from your great databases about the lymph node ratio in your group of patients?

Presenter Dr. Murray F. Brennan (New York, New York): Prof. Siewert and ourselves have been small voices in the wilderness about gastric cancer. If you think that there are over 20,000 cases in the United States, rarely do we hear discussions of gastric cancer. Compare that to the way in which we have dissected pancreatic cancer, a problem of similar magnitude, and the contrast is obvious. It is an epidemic, as Dr. Siewert has emphasized, that the fastest increasing cancer in the United States behind melanoma is proximal gastric cancer. So it is a problem that is increasing rather than decreasing.

To answer his questions specifically: We began this because of our total failure to be able to reproduce the results seen in Japan. The results in the United States are clearly far inferior, stage for stage. We believe that is predominantly a stage migration phenomenon. We did not have a system that we could commit to that anyone would follow. I think the >15 nodes is a system that can be followed and I would hope that you all go away from here today saying that it is a requirement for quality assurance in gastric carcinoma that 15 nodes must be examined.

Dr. Siewert, the pathologists obviously are important—the majority of these patients have advanced disease, and so most of the detection of the nodes are by gross macroscopic dissection. We know that there are large numbers of nodes even <5 mm that contain carcinoma, but once we have established 15 nodes being identified, there is a relative reluctance to pursue that. We performed a study previously using a fat-clearing technique. With a fat-clearing technique you can double or triple the number of identified nodes, and certainly triple the number <2 mm, some of which will have malignancy.

Regarding the lymph node ratio, the median number of nodes sampled was 21 and the median number positive is four, so it is about 19%, which would be adequate, I would think.

Dr. Michael G. Sarr (Rochester, Minnesota): I think we all would agree that the Japanese system is theoretically very attractive but impractical. And your data confirms what others have published on the use of the number of involved nodes, say, from Germany as well as from Japan. It is reassuring to see that this same concept is true in a North American trial.

I will ask three short questions and offer one potential response. The questions relate to the use of this classification. First, should we be doing a D2 or D3 lymphadectomy? Can you use your data to support an extended lymphadenectomy in light of the recently published English and Dutch trials?

Second, with the interest in micrometastases as determined with immunocytochemistry or with the new molecular techniques, how will the recognition of micrometastases (and thus a larger number of “positive” nodes) affect this classification of N staging? And third, is there a role for a sentinel lymph node biopsy with this lesion? In your manuscript you talked about the possibility of skipped nodes—will that affect this concept?

But I will offer one response to my challenge of “What is the use of this?” As you are probably well aware, the InterGroup Study is going to present an abstract at ASCO this year that finally shows in a large enough number of patients a statistical benefit to adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after “curative” resection. This is at least one response to my question of, “What is the use of this new classification?”

Dr. Brennan: I think the demonstration that you have a staging system that can provide results in experienced hands that parallels the experience in other countries is valuable both for the patient and the physician.

Secondly, to claim therapeutic results from adjuvant therapy of any kind, radiation or chemotherapy, precise classification is essential. It is very easy to show a benefit to a therapy that doesn’t need to be done. If the patient truly is N zero, as characterized by no cancer in 15 nodes, then obviously you cannot benefit them by taking more out.

I am certainly on record as saying that the trials, as described in the New England Journal by the Netherlands group, do not show a benefit to extended (D2) dissection. Any of you who read that paper and the editorial appreciate that there were large numbers of problems with that very difficult study. However, the current data does not support extended node dissection in improving survival. I believe we will continue to do it because the argument against it is increased morbidity and mortality, and we have published that we do not have an increased morbidity or mortality by an extended node dissection, and we do have accurate staging data and accurate outcome, and we will then be able to evaluate adjuvant studies.

I have very limited experience with immunohistochemistry and gastric cancer. As with all other studies, I expect it will increase the number of positive nodes. But as the vast majority of these people already have T3, N1, or N2 stage 3 gastric cancer, the finding of a few more nodes, whether it be by immunohistochemistry or fat-clearing technique, is unlikely to change things.

For that reason, I think until we have diagnostic tools that are likely to identify a greater incidence of early gastric cancer or early GE junction cancer, the concept of sentinel lymph node biopsy has very little to offer. It does identify drainage routes, but they have been well characterized by multiple studies in multiple institutions beginning in this country in the 1930s.

Dr. Frederick L. Greene (Charlotte, North Carolina): I think the discussion underlines the dynamic nature of the TNM system since it was first introduced in the 1940s. The American Joint Committee on Cancer will be using this paper and other presentations in developing the Sixth Edition of our manual, which is due for publication in 2002. As chairman-elect of the AJCC, I want to thank all of the members of the Association who will be helping with that.

My question, Dr. Brennan, relates to studies, especially using laparoscopic staging of abdominal tumors, showing that it may not be the number of nodes or location of nodes, but peritoneal cytology that is directly proportional to nodal involvement. In your institution, are you looking at peritoneal cytologic involvement of the abdomen in relationship to nodes?

Dr. Brennan: We have been proponents of laparoscopy for a number of staging systems both pancreatic and gastric. I personally believe it is actually of more value in gastric cancer than it is in pancreatic cancer.

We continue to be impressed with radiologically resectable gastric adenocarcinoma, particularly proximal lesions, which make up more than half. We continue to find greater than 20%, closer to 30%, of patients who have unidentified positive M1 disease. In those patients who have cytological washings that are positive, they act as if they are in M1 disease.

So I would think in any forward-going staging protocol and any forward-going preoperative neoadjuvant approach, it would be paramount for the patient to be laparoscoped and have cytological washings, or you will include patients inappropriately in such studies.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Martin S. Karpeh, MD, Gastric & Mixed Tumor Service, Dept. of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave., New York, NY 10021.

Presented at the 120th Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 6–8, 2000, The Marriott Hotel, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Supported by a grant from the Lawrence M. Gelb Foundation.

Accepted for publication April 2000.

References

- 1.Rohde H, Gebbensleben B, Bauer P, Stutzer H, Zieschang J. Has there been any improvement in the staging of gastric cancer? Findings from the German Gastric Cancer TNM Study Group. Cancer 1989; 64: 2465–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy BJ. TNM classification for stomach cancer. Cancer 1970; 26: 971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., 1995.

- 4.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

- 5.Sobin LH, Fleming ID. TNM classification of malignant tumors. Cancer 1997; 80: 1803–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermanek P, Wittekind C. News of TNM and its use for classification of gastric cancer. World J Surg 1995; 19: 491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanebo HJ, Kennedy BJ, Chmiel J, Steele G Jr, Winchester D, Osteen R. Cancer of the stomach. A patient care study by the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg 1993; 218: 583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B 1972; 34: 1870–220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi Y, Oshiro T, Okuyama T, et al. A simple classification of lymph node level in gastric carcinoma. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Suzuki T, et al. Superiority of a new UICC-TNM staging system for gastric carcinoma. Surgery 2000; 127: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roder JD, Bottcher K, Busch R, Wittekind C, Hermanek P, Siewert JR. Classification of regional lymph node metastasis from gastric carcinoma. German Gastric Cancer Study Group. Cancer 1998; 82: 621–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nio Y, Tsubono M, Kawabata K, et al. Comparison of survival curves of gastric cancer patients after surgery according to the UICC stage classification and the General Rules for Gastric Cancer Study by the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg 1993; 218: 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikura T, Tomimatsu S, Uefuji K, et al. Evaluation of the New American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against Cancer classification of lymph node metastasis from gastric carcinoma in comparison with the Japanese classification. Cancer 1999; 86: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii K, Isozaki H, Okajima K, et al. Clinical evaluation of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer defined by the fifth edition of the TNM classification in comparison with the Japanese system. Br J Surg 1999; 86: 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Shimizu Y, et al. The number of metastatic lymph nodes: a promising prognostic determinant for gastric carcinoma in the latest edition of the TNM classification. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187: 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JP, Jung S-E. Patients with gastric cancer and their prognosis in accordance with number of lymph node metastases. Scand J Gastroenterol 1987; 22: 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino M, Moriwaki S, Yonekawa M, Oota M, Kimura O, Kaibara N. Prognostic significance of the number of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 1991; 47: 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CW, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Tsay SH, Lui WY, P’eng FK. Relation of number of positive lymph nodes to the prognosis of patients with primary gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut 1996; 38: 525–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon SJ, Kim GS. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis in advanced carcinoma of the stomach. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 1600–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isozaki H, Okajima K, Kawashima Y, et al. Prognostic value of the number of metastatic lymph nodes in gastric cancer with radical surgery. J Surg Oncol 1993; 53: 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiu MH, Moore E, Sanders M, et al. Influence of the extent of resection on survival after curative treatment of gastric carcinoma. A retrospective multivariate analysis. Arch Surg 1987; 122: 1347–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jatzko GR, Lisborg PH, Denk H, Klimpfinger M, Stettner HM. A 10-year experience with Japanese-type radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer outside of Japan. Cancer 1995; 76: 1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee WJ, Lee PH, Yue SC, Chang KC, Wei TC, Chen KM. Lymph node metastases in gastric cancer: significance of positive number. Oncology 1995; 52: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunt AM, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ, et al. Lymph node retrieval in a randomized trial on Western-type versus Japanese-type surgery in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 2289–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Candela FC, Urmacher C, Brennan MF. Comparison of the conventional method of lymph node staging with a comprehensive fat-clearing method for gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer 1990; 66: 1828–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]