Abstract

Objective

To analyze a series of patients treated for recurrent or chronic abdominal wall hernias and determine a treatment protocol for defect reconstruction.

Summary Background Data

Complex or recurrent abdominal wall defects may be the result of a failed prior attempt at closure, trauma, infection, radiation necrosis, or tumor resection. The use of prosthetic mesh as a fascial substitute or reinforcement has been widely reported. In wounds with unstable soft tissue coverage, however, the use of prosthetic mesh poses an increased risk for extrusion or infection, and vascularized autogenous tissue may be required to achieve herniorrhaphy and stable coverage.

Methods

Patients undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction for 106 recurrent or complex defects (104 patients) were retrospectively analyzed. For each patient, hernia etiology, size and location, average time present, technique of reconstruction, and postoperative results, including recurrence and complication rates, were reviewed. Patients were divided into two groups based on defect components: Type I defects with intact or stable skin coverage over hernia defect, and Type II defects with unstable or absent skin coverage over hernia defect. The defects were also assigned to one of the following zones based on primary defect location to assist in the selection and evaluation of their treatment: Zone 1A, upper midline; Zone IB, lower midline; Zone 2, upper quadrant; Zone 3, lower quadrant.

Results

A majority of the defects (68%) were incisional hernias. Of 50 Type I defects, 10 (20%) were repaired directly, 28 (56%) were repaired with mesh only, and 12 (24%) required flap reconstruction. For the 56 Type II defects reconstructed, flaps were used in the majority of patients (n = 48; 80%). The overall complication and recurrence rates for the series were 29% and 8%, respectively.

Conclusions

For Type I hernias with stable skin coverage, intraperitoneal placement of Prolene mesh is preferred, and has not been associated with visceral complications or failure of hernia repair. For Type II defects, the use of flaps is advisable, with tensor fascia lata representing the flap of choice, particularly in the lower abdomen. Rectus advancement procedures may be used for well-selected midline defects of either type. The concept of tissue expansion to increase both the fascial dimensions of the flap and zones safely reached by flap transposition is introduced. Overall failure is often is due to primary closure under tension, extraperitoneal placement of mesh, flap use for inappropriate zone, or technical error in flap use. With use of the proposed algorithm based on defect analysis and location, abdominal wall reconstruction has been achieved in 92% of patients with complex abdominal defects.

Abdominal wall reconstruction may be necessary after failed closure of a celiotomy wound, or when components of the abdominal wall are either injured or absent. Specific criteria used to identify patients who may require special closure techniques for an abdominal wall defect include one or more of the following: 1) large size (>40 cm2); 2) absence of stable skin coverage; 3) recurrence of defect after prior closure attempts; 4) infected or exposed mesh; 5) patient who is systemically compromised (e.g., intercurrent malignancy); 6) compromised local abdominal tissues (e.g., irradiation, corticosteroid dependence); and 7) concomitant visceral complications (e.g., enterocutaneous fistula).

Decisions regarding technique for abdominal wall reconstruction are based on an assessment of the defect by location, extent (layers involved), and etiology. Reconstructive options include direct tissue closure, prosthetic mesh, local advancement or regional flaps, distant flaps, or combined flap and mesh. Although previous studies have examined results with specific techniques for mesh 1–8 or flap 9–11 use, data comparing results of mesh and flaps in a population of patients with complex abdominal hernias is not available. The purpose of this study is to compare flap and mesh closure techniques and to establish a treatment protocol for the reconstruction of complex recurrent or recalcitrant abdominal wall hernias.

METHODS

Patients undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction between 1988 and 2000 who presented with complex abdominal hernias as determined by specific risk factors were reviewed for defect-related data, techniques selected for reconstruction, and outcome. In 104 consecutive patients analyzed (61 female, 43 male), the following information was obtained by record review and patient exam: hernia etiology and size, average time present, technique of reconstruction, and postoperative results, including complications and recurrences. Patients who underwent urgent closure of acute abdominal defects as a temporary measure were not included in this study. Two patients presented with two abdominal wall defects that were treated separately, resulting in 106 total defects for analysis.

The primary etiology for the defects was as follows: incisional hernia (n = 72; 68%); tumor resection (n = 16, 15%); infection (n = 10, 9%); irradiation (n = 4, 4%); and trauma (n = 4, 4%). Defects had been present an average of 12.6 months. Size of the defects ranged from 40 cm2 to 900 cm2 (mean: 217 cm2). Patients were divided into two treatment groups: Type I (n = 50), hernias associated with stable skin coverage, and Type II (n = 56), hernias with absent or unstable skin coverage (e.g., infected or exposed mesh, enterocutaneous fistula, radiation necrosis).

Incisional hernias had frequently failed at least one prior attempt at closure (n = 35; 49%), and 25 of these (71%) had previously undergone attempted mesh repair. Twenty-four of the patients with recurrence (69%) had one prior attempt at reconstruction, three patients (8%) had two prior attempts, and eight patients (23%) had three or more prior attempts at repair (maximum number of prior attempts: 7).

Forty-eight patients (46%) were considered to be compromised hosts, with the following associated problems: 18 patients had active/concurrent malignancies, 14 were steroid-dependent (transplant) patients, 12 patients had a history of radiation therapy to the abdomen, and four patients had recently finished chemotherapy. Four patients had enterocutaneous fistulae and one patient had a vesiculocutaneous fistula.

A zone was assigned based on the location of the abdominal wall defect. Zone designation determines areas that are covered by specific flaps and was used to compare treatment selection and results (Fig. 1). Zones were designated as follows:

Figure 1. Reconstructive zones of the abdomen.

Zone 1A: upper midline defects with extension across the midline;

Zone 1B: lower midline defects with extension across the midline;

Zone 2: upper quadrant defect of the abdomen; and

Zone 3: lower quadrant defect of the abdomen.

Abdominal defects were initially analyzed by zones. When defects included areas of two or more zones, the zone of major involvement was used for comparison of results.

Type I Defects (n = 50)

The distribution of defects by zone was as follows: Zone 1A, n = 6; Zone 1B, n = 15; Zone 2, n = 4; and Zone 3, n = 25. Forty-five (90%) of these defects were incisional hernias, of which 15 (33%) were recurrent. The remaining five defects were secondary to trauma (n = 4) or tumor resection (n = 1). The average time the hernia was present was 17.5 months, and the average size of these defects was 161 cm2. Postoperative follow-up averaged 15 months.

Type II Defects (n = 56)

The distribution of defects by zone was as follows: Zone 1A, n = 12; Zone 1B, n = 20; Zone 2, n = 7; and Zone 3, n = 17. There were 27 incisional hernias, 20 (74%) of which had undergone prior unsuccessful attempt at repair. The remaining defects resulted from en bloc tumor resection (n = 15), infection (n = 10), or radiation necrosis (n = 4). The average time the hernia was present was 8.2 months. Type II defects were larger than Type I, averaging 267 cm2. Mean postoperative follow-up was 12 months.

Entire Population

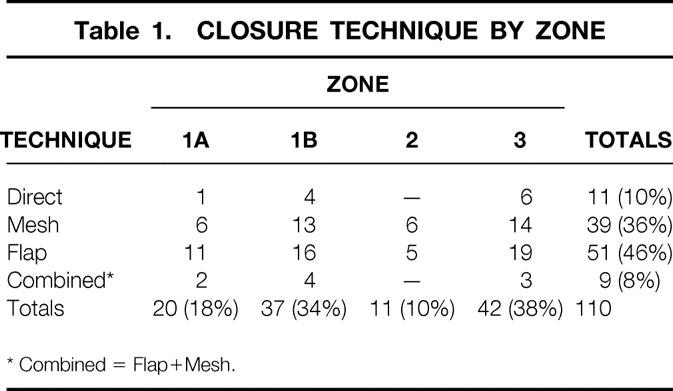

Reconstructive procedures were selected based on defect analysis, including components and location of the defect. The following techniques were used: direct closure (n = 11, 10%), prosthetic mesh (n = 39; 35%); flap closure (n = 51; 47%); or combination of flap and mesh closure (n = 9; 8%) (Table 1). Type I defect closure techniques included direct repair, mesh, advancement flaps, or regional flaps. Type II defects were reconstructed with either regional or distant flaps, combined with prosthetic mesh when fascia was inadequate.

Table 1. CLOSURE TECHNIQUE BY ZONE

* Combined = Flap+Mesh.

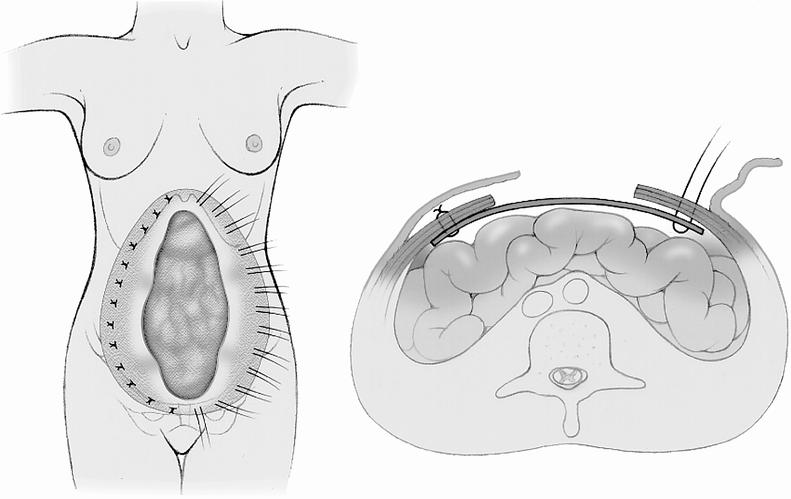

Direct closure was generally used for small defects (<5 cm in width), with adequate soft tissue coverage, and sufficient fascia present to allow for a tension-free closure. Reconstruction with mesh alone used polypropylene (Prolene or Marlex) or polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) mesh, placed either intraperitoneally or extraperitoneally as a fascial substitute, extrafascially as an onlay reinforcement, or combined as a dual-layer interposition with Prolene mesh on the deep surface. Prolene was used in 33 of these repairs (85%), placed intraperitoneally in 19 cases (58%). The technique of intraperitoneal Prolene mesh placement (Fig. 2), represents a modification of mesh technique described by McCarthy and Twiest. 8

Figure 2. Technique of intraperitoneal placement of Prolene mesh (modified from McCarthy and Twiest 8).

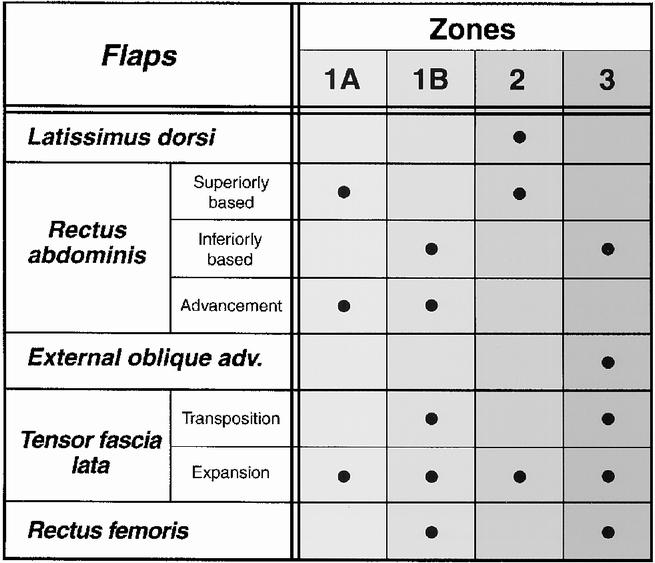

Flaps were selected (Type I defects, n = 12; Type II defects, n = 48) based on their availability and arc of rotation to specific zones of the abdomen as defined by their blood supply 11,12 (Fig. 3). Regional flaps (rectus abdominis, external oblique) were used in 58% (n = 7) and 60% (n = 29) of Type I and II defects, respectively, and represented the most common type of flap used in this study (Table 2). The rectus abdominis is frequently used as a superiorly or inferiorly based muscle or musculocutaneous flap (n = 10). By release of selected attachments to the lateral abdominal musculature, it is possible to advance the rectus muscle as a flap with its anterior fascial sheath for Zone 1A and 1B defects. These advancement modifications (Fig. 4) include the following variations for rectus advancement musculofascial flap: release of both external oblique and posterior rectus sheath (see Fig. 4A), or components separation technique 13; release of external oblique aponeurosis (see Fig. 4B); rectus turnover 14; and rectus musculocutaneous advancement with release of internal oblique (see Fig. 4C).

Figure 3. Flaps used in abdominal wall reconstruction. Vascular pedicles: Latissimus dorsi–thoracodorsal; rectus abdominis–superior and inferior deep epigastrics; external oblique–segmental branches of intercostals; tensor fascia lata–lateral femoral circumflex; rectus femoris–lateral femoral circumflex. 12

Table 2. FLAP SELECTION BY ZONE

Figure 4. Rectus advancement techniques, demonstrating dissection planes.

Distant flap options included the latissimus dorsi, tensor fascia lata (TFL), and rectus femoris muscles (see Fig. 3). In three cases involving very large defects (25×30 cm, 20×30 cm, 5×15 cm) spanning more than one zone, tissue expanders were placed beneath a TFL flap with gradual expansion over 3 to 6 months to increase the fascial surface area and arc of rotation of the flap for subsequent staged reconstruction.

Complications were classified as either major or minor; major complications were defined by the need for reoperation, but did not represent failure of the hernia repair. Analysis of reconstructive success (i.e., hernia recurrence rate) was based on a minimum follow-up period of 2 months. Average time of follow-up was 13.7 months (range 2–133 months).

RESULTS

Closure techniques were analyzed according to location of the defect (see Table 1). Most Type I defects were reconstructed using mesh alone (n = 28; 56%), while the most Type II defects required regional or distant flaps (n = 48; 80%). When flap selection was analyzed by zone, Zone 1A and 1B defects were most commonly reconstructed with rectus abdominis advancement flaps. Zone 3 defects were most commonly reconstructed with the TFL flap (see Table 2).

There were a total of 31 complications (29%), 13 of which required reoperation (12%). Analyzed by type of defect, there were three major complications (6%) after repair of Type I defects and 10 major complications (17%) after repair of Type II defects. Major complications (n = 13) included infection (n = 5), flap-related (n = 5), donor-site–related (n = 2), and seroma (n = 1). The five flap-associated complications involved Type II defects; only one needed further flap coverage for distal skin necrosis of a TFL flap. The partial flap loss was not associated with a hernia recurrence. Minor complications (n = 18) included cellulitis (n = 5), flap-related (n = 4; partial epidermolysis, distal tip necrosis, partial dehiscence of flap inset), systemic (n = 4; prolonged pain, pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolus), donor-site–related (n = 3), and seroma (n = 2).

Overall hernia recurrence rate was 8% (n = 9). Data about subsequent repair of these recurrent hernias are not included in this study. There were five recurrences for Type I defects (10%) and four recurrences for Type II defects (7%). Recurrences were further analyzed according to location of the defect and technique of reconstruction (Table 3). Attempts at direct repair yielded the highest overall recurrence rate (27%), followed by combination repair (11%), flap-only repair (6%), and mesh-only reconstruction (5%).

Table 3. RECURRENCE BY TECHNIQUE

* Combined = Flap+Mesh.

DISCUSSION

Incisional hernia represents the most common wound complication after abdominal surgery, with a reported incidence rate of 2% to 11% and a recurrent herniation rate of 20% to 46%. 15 Careful evaluation of the patient who presents with a complex abdominal defect reveals predisposing factors for herniation, including inadequate local fascial and muscular layers due to prior tissue loss; muscle denervation or vascular insufficiency due to prior irradiation or infection; wound infection; obesity; chronic pulmonary disease; malnutrition; sepsis; anemia; corticosteroid dependency; and/or concurrent malignant process. 15–18 All patients in this series demonstrated one or more risk factors that predispose to problems with abdominal closure. Indeed, 49% of the patients with an incisional hernia had already failed at least one prior attempt at abdominal wall reconstruction.

Direct repair should be limited to patients with small defects (<5 cm in diameter) and few associated risk factors for poor wound healing. The recurrence rate in this study was highest for those defects treated by direct closure, 27% (3/11). With preexisting loss of abdominal wall layers, excessive tension at the closure site results in ischemia 4,16 and eventual failure of the repair. This problem is avoided with the use of mesh alone or combined with a flap.

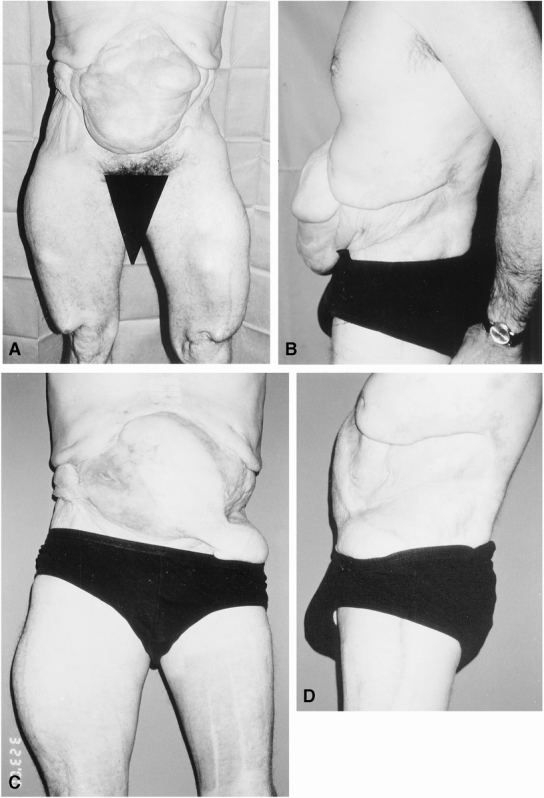

In the noninfected wound with stable overlying skin (Type I), mesh is preferred to restore the integrity of the abdominal wall (Fig. 5). When soft tissue coverage is also inadequate (Type II), regional or distant flaps are necessary, either alone or in combination with mesh (Fig. 6). Although both nonabsorbable polypropylene (Marlex and Prolene) and polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) mesh are advocated for abdominal wall reconstruction, 1,16,17,19 Prolene was the preferred synthetic fascial substitute in this series (75% of all hernia repairs in which mesh was used). Prolene is relatively inert, appears to have adequate strength, and unlike Gore-Tex, allows for tissue incorporation and ingrowth of granulation tissue. 16,17 Placed intraperitoneally, visceral complications have not been observed. If available, however, omentum should be placed between the bowel and mesh.

Figure 5. Mesh repair of Type I hernia. (A) Recurrent Zone 3 traumatic hernia, anterior view. (B) Preoperative lateral view. (C) Mesh repair of Type I hernia (intraperitoneal mesh technique); 1-year postoperative anterior view demonstrates stable coverage over mesh repair. (D) Postoperative lateral view demonstrates restoration of abdominal wall continuity.

Figure 6. Expanded distant flap repair of extensive Type II defect. (A) Anterior view of extensive abdominal wall defect involving Zones 1A, 1B, 2 and 3 with skin graft over viscera; bilateral expanders in place in territory of tensor fascia lata flap. (B) Lateral preoperative view. (C) Postoperative (4 months) anterior view demonstrates stable abdominal wall reconstruction. (D) Postoperative lateral view demonstrates restoration of abdominal wall continuity.

Past studies have demonstrated a complication rate of 18% to 50%1,2 and hernia recurrence of 11%16 with mesh use for complex abdominal wall reconstruction. In this study, the observed complication rate of 9% and failure rate of 5% using mesh alone to reconstruct all types of complex defects compares favorably. In the two repair failures, mesh was used extraperitoneally as a fascial substitute in one case, and as an overlay reinforcement in the other. The advantage of anchoring the mesh intraperitoneally is that U stitches are placed lateral to the defect in normal, innervated layers of the abdominal wall (external and internal oblique musculature), to ensure fixation through well-vascularized tissue (see Fig. 2). Using this method of intraperitoneal placement of Prolene mesh, 8 no hernia recurrence occurred in either group.

Flaps were used in 12 patients with Type I defects (Zone 3, n = 8; Zone 1B, n = 4). The decision to use vascularized flaps in this subset was not related to defect size (mean = 127 cm2) or location, but rather was correlated with associated factors including a history of failed mesh, previous infection, radiation to the abdominal wall, or corticosteroid use. In fact, one or more of these factors was present in 75% of these patients. Flap reconstruction for Type I defects in this series was effective in restoring abdominal wall continuity in 92% of patients.

Patients with Type II defects have a greater risk of infection and mesh extrusion due to absent or unstable skin coverage. Therefore, flap coverage is frequently required for abdominal wall reconstruction. Regional and distant flaps were used in 80% of these patients (13% were combined with mesh). Although minor complications after flap reconstruction were increased compared to Type I patients requiring flaps (Type I, 8%; Type II, 23%), and major complications requiring reoperation were also increased (Type I, 0%; Type II, 17%), the recurrence rate for repair of Type II defects using flaps was 6%.

In this study, the overall hernia recurrence rate after flap reconstruction was 7% (n = 4). Previous studies examining flap reconstruction of abdominal wall defects have reported complication rates of 44%20 and recurrence rates ranging from 5% to 42%. 21,22 Three of the four flap failures in this series were felt to be due to inappropriate flap selection. Attempts to use a specific flap beyond its safe arc of rotation results in excessive tension of the flap pedicle with an increased risk of flap compromise. When flaps were chosen for recommended zones of reconstruction (Fig. 7), only one failure (2%) was noted.

Figure 7. Flap options for abdominal wall reconstruction, by zones.

For Zones 1A and 1B, rectus advancement procedures (see Fig. 4) are particularly useful when operating on severely debilitated patients, or when avoidance of mesh contact with the viscera is preferred due to concurrent fistula closure or visceral radiation injuries. Release of the lateral fascial attachments allows advancement of the rectus abdominis and its anterior fascia to restore central abdominal wall integrity. Rectus advancement techniques also do not require additional dissection at a distant flap donor site. 13,22,23 Because extended release of lateral fascial attachments may result in mild lateral abdominal weakness in the healthy, active patient, intraperitoneal mesh is preferred over rectus advancement techniques in healthy patients with Type I defects.

When a distant flap is required for Zone 1B or 3 full-thickness defect reconstruction, the tensor fascia lata flap is recommended, because it provides both a large area of vascularized fascia and cutaneous coverage. 9–11,19,24–26 It is most useful when removal of infected mesh is required. Further application of the TFL flap to include upper abdominal wall coverage (Zones 1A and 2) has also been possible using tissue expansion. This approach increases the vascular territory 27 and fascial dimensions of the flap, and facilitates donor site closure. This technique, not previously described for fascial expansion, was first used in 1992 in this series for a patient requiring removal of infected Marlex mesh in Zones 2 and 3. Subsequently, the expanded TFL has been successfully used in two other cases (see Fig. 6).

In summary, analysis of the patient who presents with a complex abdominal wall hernia, based on the criteria used in this study, must include an assessment of the components and location of the defect. Adequate tissue for direct closure is generally not available. When stable skin coverage is present, intraperitoneal mesh placement is recommended. When cutaneous coverage is absent or compromised, abdominal wall reconstruction generally requires use of a flap. Regional and distant flaps suitable for abdominal wall reconstruction have been identified based on a reliable vascular pedicle and safe arc of rotation to the specific zone on the abdominal wall.

Careful evaluation of outcomes yielded useful information about potential pitfalls in abdominal wall reconstruction. Causes of failure (n = 9; 8%) included direct closure (n = 3), extraperitoneal use of mesh (n = 2), inappropriate flap selection for recommended zone of defect (n = 3), and technical failure (n = 1). This study identified criteria that predict complexity in abdominal wall reconstruction. Both mesh and flap techniques, when appropriately selected, are safe and effective in the restoration of abdominal wall continuity. Use of the proposed algorithm for defect analysis and technique selection has resulted in successful abdominal wall reconstruction in the majority of patients encountered.

Discussion

Dr. J. Patrick O’Leary (New Orleans, Louisiana): It is very hard for me to put my head around this problem. It is almost as though Dr. Mathes has presented us with 106 spectacular problems in surgery. It is a common problem and all of us have this kind of a problem in our practice. What he has shown us are a number of other options that might be used.

The problem I have always had with the abdominal cavity is the wall of the abdominal cavity is dynamic and it is fixed at a variety of points, at the cartilage of the chest, the pubis, and the iliac crest. It is always hard for me to figure out how actually to close the hernia that is in juxtaposition to those areas.

I would like to ask a couple of questions. When do you use mesh? What went into your decision to use mesh? And better yet, when do you not use mesh? From your data, 71% of your patients had mesh in their previous repair and it had failed. Could you determine from your data why these patients failed? They already had mesh placed—what was the problem with it?

The next question deals with the position of the mesh, intraperitoneal versus extraperitoneal. When do you choose to place it intraperitoneally? It would seem to me from your presentation that you do it all the time.

The final question deals with the potential of an intraabdominal compartment syndrome. My most recent foray in this area ended up with a very nice closure but a marked increase in intraabdominal pressure that ultimately required us to take down our closure. Do you measure intraabdominal pressures? How do you ascertain when the closure is too tight?

Presenter Dr. Stephen J. Mathes (San Francisco, California): Regarding fixation of mesh to bone, this can be difficult. I usually suture directly into bone periosteum or use a metal screw with attached wire suture (Mitek). Fixation of mesh to bone has been effective with these techniques. In the area of the costal margin, placement of suture around the costal margin will fix the mesh.

When do I use mesh? In general, if the abdominal wall skin coverage is stable, this is an excellent time to consider mesh. When do I not use it? Obviously, when the skin is unstable, I worry about lack of skin stability or skin grafts over mesh, so I would then use a flap alone or in conjunction with mesh.

In patients who have infected mesh removed—and that did represent about 14% of our patients—it is better not to use mesh in a chronically infected wound. In this instance, resect infected mesh and use an autogenous flap selected based on the flap arc of rotation to involved zone. Also, in patients who have small bowel or vesicocutaneous fistula closure, flap use for abdominal closure is preferred. When there were no visceral problems requiring repair at the time of the abdominal reconstruction, intraperitoneal mesh has been routinely used for fascial replacements in Type I patients. In these patients, no intraabdominal complications such as fistulae or bowel obstruction due to adhesions have occurred.

Most mesh failures when used as a substitute for fascia occur due to failure to anchor the mesh to healthy fascia in proximity to the hernia defect. You are more likely to fix the mesh distant to the hernia defect where the fascia and muscles are still innervated if you use the technique of the intraperitoneal approach. Certainly there are many reported series that show extraperitoneal mesh effective in hernia repair. Both techniques require preparation of innervated normal musculofascial layers to anchor the mesh in the closure of the abdominal defect.

As far as the abdominal compartment syndrome as a consequence of abdominal closure, I am glad you have commented on this potential complication. One patient in this series appeared to demonstrate the abdominal compartment syndrome when the technique of rectus advancement was used for closure of a 12-cm defect in Zone 1A and in 1B. Although mobilization of both rectus abdominis muscles as advancement flaps allowed defect closure, there was possible visceral compression due to tight closure. This patient also had fluid overload, so it was difficult to determine whether it was fluid overload or compartment syndrome. Nevertheless, the patient was returned to surgery where the advancement flaps were released and a distant flap rather than a direct closure using the advancement techniques corrected the tight abdominal closure.

Dr. R. Scott Jones (Charlottesville, Virginia): Dr. Mathes and his colleagues have described an organized approach to very difficult problems that we all encounter from time to time. I wanted to ask a couple of questions and ask if he could be willing to elaborate on a couple of points.

First, I realize that this presentation was in stable patients and reconstruction. But I would like to ask if you would give us some tips or advice about the acute situation when we are dealing with a patient who has had acute traumatic loss of tissue from the abdominal wall or if we have encountered a severe necrotizing infection, what guiding principles should we use during that time in terms of debridement or staging to allow the techniques that you describe so well to be employed optimally later?

The other question that I wanted to ask you—you have mentioned the different types of prosthetic material that are available. Are there any that you would choose in one circumstance versus another? In other words, if you were doing a definitive construction would you use one thing, if you are doing a staged procedure, for example, would you use something else?

The last question I would like to ask is, is there ever a role for split-thickness skin grafting in managing the skin deficiencies in these problems?

Dr. Mathes: In regard to acute abdominal loss, although this data is not included in this study, we have experience in this problem. Our approach has been to recommend aggressive debridement and mesh closure for wound management in these patients. The temptation is to try, after completion of repair of intraabdominal organ injury, to close the abdominal defect under tension. This tension closure predisposes to further necrosis of tissue with dehiscence and wound infection.

For this reason, our approach is a very wide debridement and then use of a permanent mesh—in this instance Prolene mesh is preferred. Skin is left open with use of frequent dressing changes over the exposed mesh. Over time, as the patient stabilizes, granulation tissue will cover this mesh, allowing either skin grafts if wound is extensive or early mesh removal after edema has resolved and direct abdominal closure using remaining fascial layers.

There are instances when you know multiple debridements will be required. In this situation, the use of the absorbable meshes such as Vicryl or Dexon may be considered. The absorbable meshes, however, are useful if fascial replacement is only temporary. In some instances—and I know Dr. O’Leary has a similar experience—a vacuum dressing can be helpful as another way of controlling the wound during the healing process. As discussed in our report, Prolene remains the mesh of choice based on its smooth surface and absence of visceral complications in our patients.

The second principle for use of mesh is providing adequate tension on the mesh. Many of the patients who present with failed mesh closure have a lot of wrinkling in the mesh and it really isn’t very taut. If mesh is used as a fascial replacement, it should be tight to work well. Although Gore-Tex has also been used effectively for abdominal wall fascial replacement, experimental studies have demonstrated that polypropylene mesh is more resistant to infection and there is superior incorporation of collagen into the mesh as compared to polytetrafluoroethylene.

Lastly, you asked about skin grafts. As you saw, the last patient, who had multiple problems, did have skin grafts used as a temporary coverage on exposed viscera. He survived his synergistic gangrene but has suffered a great deal of morbidity from this enormous hernia defect. The skin graft should be kept in your armamentarium as a useful technique when you want coverage and you are not prepared to commit to a flap or to mesh.

Dr. Carlos A. Pellegrini (Seattle, Washington): I wonder if you have considered approaching the 1A or 1B patients, the patients with a stable coverage of skin, laparoscopically? We started approximately 4 years ago working on these patients using the minimally invasive approach and found that it facilitates, in many ways, the performance of the operation and it follows many of the principles that you pointed out.

We use mesh in all the patients, we place it intraperitoneally, just like you did. Using the tension-free principle, we anchor the mesh as far laterally as needed and we fix it percutaneously. I think it gives you the great advantage of not having a wound to be concerned about. It abolishes infections and other problems related with it. For patients with stable skin coverage, even when they have complex defects, I think it is a good approach. Could you comment?

Dr. Mathes: I would agree, there is definitely a place for the laparoscopic approach, particularly for the 1A and 1B defects. However, I would caution one to reserve this technique for the initial attempt at repair. In the patients with multiple recurrences of the ventral hernia, there are often a number of adhesions that may require direct visualization for release, although with increasing experience in laparoscopic surgery, the laparoscopic still may be a reasonable approach for this type of patient.

Also, in our literature, recent reports have shown that the components separation technique for rectus abdominis advancement flaps can be accomplished using the laparoscopic approach. With laparoscopic visualization of the rectus sheath, attachments of the lateral rectus sheath are released, allowing mobilization of the rectus abdominis bilaterally as an advancement flap for regional flap closure of a complex hernia defect. This technique does have potential for use in selected patients.

Dr. Harvey J. Sugerman (Richmond, Virginia): I would like to bring a word of extreme caution regarding the intraperitoneal placement of Prolene mesh. We have had a number of patients in whom this has been performed by other surgeons who have required another intraabdominal procedure and there are often extremely dense bowel adhesions to the mesh, making the surgery extremely difficult. I would only support this approach if there were enough omentum to completely protect the bowel from coming into contact with the mesh. Furthermore, there is a major risk of intestinal fistulas developing with the intraperitoneal placement of the mesh. Having had a significant experience with incisional hernia repairs in over 400 patients in our morbidly obese population, we have had only a 1% recurrence rate when the Prolene mesh is placed anterior to the fascia (Surg Gynecol Obstet 1985;161:181;Am J Surg 1996;171:80). The mesh is sutured with interrupted Prolene sutures to the anterior fascia on one side; interrupted Prolene sutures are placed in the anterior fascia on the opposite side; the hernia is closed in the midline with running Prolene sutures, and the previously placed sutures are passed through the mesh and tied down. This lays the mesh down smooth and tight on top of the fascia as an onlay graft away from the peritoneum and bowel.

Your advancement flap for the much larger, complicated hernias are outstanding. I commend you that you haven’t had intestinal fistulas with intraperitoneal Prolene mesh. I can tell you that the adhesions of bowel to the intraperitoneal mesh can be devastating.

Dr. Mathes: I appreciate your comments and your extensive experience with this problem. Mine has been a little different in that I have used the Prolene mesh in a number of abdominal wall defects acutely where one would expect the most problem with adhesions. On reexploration on these patients to replace the mesh with a regional or distant flap for abdominal wall reconstruction, extensive adhesions have not been present. I attribute this finding to the fact that there is again a great deal of tension on this mesh and it is not wrinkled and probably there are no rough edges for adhesions of small bowel.

But you are correct that one certainly has to be aware of this potential complication and take extra effort to avoid injury to small bowel both during the time of the abdominal wall reconstruction and on occasion of reexploration.

Dr. Anthony A. Meyer (Chapel Hill, North Carolina): Just one brief question on a patient like the last one you showed who had a large defect, had skin grafted over it. Frequently we have seen patients who have had abdominal compartment syndrome after trauma or infection from necrotizing soft tissue infections wherethey are very edematous, and in order to get coverage, you put on an absorbable mesh, and after that granulates, you skin-graft it. When they come back, they require permanent mesh to close it.

What I have done on several patients is to incise the skin graft up to the middle in a vertical fashion and then by the time you have taken everything down and put the mesh in place and sutured it and tied your stitches, the skin graft has demarcated enough that you can trim away the dead stuff and take the residual healed grafted skin, and just let it lay back down over the mesh, which saves you the flap coverage. It may not be quite as potentially good coverage, but the skin is still viable, and heals. It avoids having to do anything more complex. Have you ever used that or tried to use it?

Dr. Mathes: I would agree that in the patients who have difficult problems immediately after major surgery and have dehiscence or evisceration, all the abdominal layers are really still there but they are retracted apart. During the acute phase, one may elect to use either temporary mesh or simply to use skin grafts for immediate coverage.

Later, when the patient is fully stabilized and edema has resolved, the skin grafts are removed and, as you have noted, you frequently can mobilize the abdominal wall layers and close directly. On the lady with the radiation problem from gastric sarcoma, these principles are demonstrated. Most of her layers were still there, but they were retracted apart due to postoperative dehiscence. Rather than direct closure on her, component separation of bilateral rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flaps were used for closure because of the fibrosis from the prior radiation. But without injury to the lateral abdominal structures, a direct closure is certainly reasonable after skin graft removal.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Stephen J. Mathes, MD, 350 Parnassus Ave., Suite 509, San Francisco, CA, 94143.

Presented at the 120th Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 6–8, 2000, The Marriott Hotel, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Accepted for publication April 2000.

References

- 1.Usher FC. A new plastic prosthesis for repairing tissue defects of the chest and abdominal wall. Am J Surg 1959; 97: 629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs E, Blaisdell FW, Hall AD. Use of knitted Marlex mesh in the repair of ventral hernias. Am J Surg 1965; 110: 897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilsdorf RB, Shea MM. Repair of massive septic abdominal wall defects with Marlex mesh. Am J Surg 1975; 130: 634–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathes SJ, Stone HH. Acute traumatic losses of abdominal wall substance. J Trauma 1975; 15: 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usher FC. New technique for repairing incisional hernias with Marlex mesh. Am J Surg 1979; 138: 740–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voyles CR, Richardson JD, Blank KI, et al. Emergency abdominal wall reconstruction with polypropylene mesh: short-term benefits versus long-term complications. Ann Surg 1981; 194: 219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone HH, Fabian TC, Turkleson ML, Jurkiewicz MJ. Management of acute full-thickness losses of the abdominal wall. Ann Surg 1981; 193: 612–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy JD, Twiest MW. Intraperitoneal polypropylene mesh support of incisional herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 1981; 142: 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wangensteen OH. Repair of recurrent and difficult hernias and other large defects of the abdominal wall employing the iliotibial tract of fascia lata as a pedicles flap. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1934; 59: 766–780. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahai F, Silverton JS, Hill HL, Vasconez LO. The tensor fascia lata musculocutaneous flap. Ann Plast Surg 1978; 1: 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bostwick J, Hill HL, Nahai F. Repairs in the lower abdomen, groin or perineum with myocutaneous or omental flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979; 63: 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Reconstructive Surgery: Principles, Anatomy and Technique. Churchill Livingstone; 1997:565–615, 991–1003, 1043–1083, 1233–1245, 1271–1292.

- 13.Ramirez OM, Ko MJ, Dellon AL. “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990; 86: 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeFranzo AJ, Kingman GJ, Sterchi JM, et al. Rectus turnover flaps for the reconstruction of large midline abdominal wall defects. Ann Plast Surg 1996; 37: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Read RR. Ventral, epigastric, umbilical, spigelian and incisional hernias. In: Cameron JL, ed. Current Surgical Therapy. 5th ed. Mosby; 1995:491–496.

- 16.Larson GM, Vandertoll DJ. Approaches to repair of ventral hernia and full-thickness losses of the abdominal wall. Surg Clin N Am 1984; 64: 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurwitz DJ, Hollins RR. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall and groin. In: Cohen M, ed. Mastery of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Boston: Little, Brown; 1994:1349–1359.

- 18.Lowe JB, Garza JR, Bowman JL, et al. Endoscopically assisted “components separation for closure of abdominal wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105; 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cederna JP, Davies BW. Total abdominal wall reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 1990; 25: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams JK, Carlson GW, deChalain T, et al. Role of tensor fasciae latae in abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;1998; 101:713–718. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Shestak KC, Edgington HJD, Johnson RR. The separations of anatomic components technique for the reconstruction of massive midline abdominal wall defects: anatomy, surgical technique, applications and limitations revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105: 731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson GW, Hester TR, Coleman JJ. The role of tensor fasciae latae musculocutaneous flaps in abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Surg Forum 1988; XI: 151. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas WO, Parry SW, Rodning CB. Ventral/incisional abdominal herniorrhaphy by fascial partition/release. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993; 91: 1080–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White DN, Pearl RM, Laub DR, DeFiebre BK. Tensor fascia lata myocutaneous flap in lower abdominal wall reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 1981; 7: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caffee HH. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall by variations of the tensor fasciae latae flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983; 71: 348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein LP, Kovachev D, Chaglassian T. Abdominal wall reconstruction. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 1986; 20: 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austad ED, Thomas SB, Pasyk K. Tissue expansion: dividend or loan? Plast Reconstr Surg 1986; 78: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]