Abstract

Objective

To present the survival results for patients with colorectal carcinoma metastases who have undergone liver resection after being staged by [18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).

Summary Background Data

Hepatic resection is standard therapy for colorectal metastases confined to the liver, but recurrence is common because of the presence of undetected cancer at the time of surgery. FDG-PET is a sensitive diagnostic tool that identifies tumors based on the increased uptake of glucose by tumor cells. To date, no survival results have been reported for patients who have actually had liver resection after being staged by FDG-PET.

Methods

Forty-three patients with metastatic colorectal cancer were referred for hepatic resection after conventional tumor staging with computed tomography. FDG-PET was performed on all patients. Laparotomy was performed on patients not staged out by PET. Resection was performed at the time of laparotomy unless extrahepatic disease or unresectable hepatic tumors were found. Patients were examined at intervals in the preoperative period.

Results

FDG-PET identified additional cancer not seen on computed tomography in 10 patients. Surgery was contraindicated in six of these patients because of the findings on FDG-PET. Laparotomy was performed in 37 patients. In all but two, liver resection was performed. Median follow-up in the 35 patients undergoing resection was 24 months. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival at 3 years was 77% and the lower 95% confidence limit of this estimate of survival was 60%. This figure is higher than 3-year estimate of survival found in previously published series. The 3-year disease-free survival rate was 40%.

Conclusions

Preoperative FDG-PET lessens the recurrence rate in patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal metastases to the liver by detection of disease not found on conventional imaging.

Hepatic resection is a standard treatment for a subset of patients with colorectal carcinoma metastatic to the liver. Strict selection criteria for resection are mandatory because recurrences are common and there is no survival benefit if any residual disease remains after hepatic resection. 1 The selection criteria are that the primary colorectal cancer must be resectable with negative margins or must have been resected with negative margins. There can be no extrahepatic metastases, with the possible exception of one or a few resectable lung metastases, and it must be possible to resect hepatic tumors completely while still leaving enough hepatic parenchyma to provide adequate postoperative liver function.

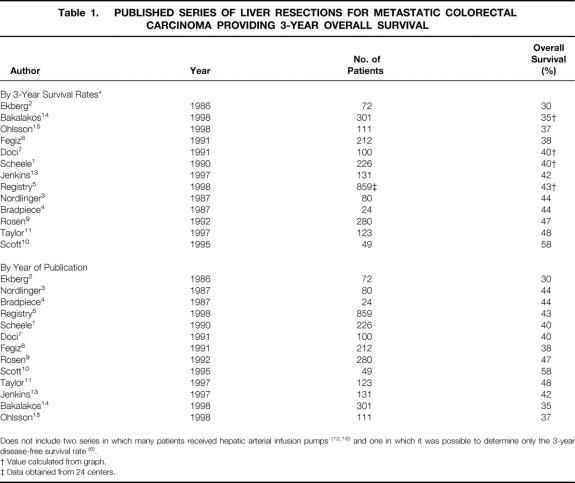

Several staging tools have been used to assess whether these criteria have been met before hepatic resection. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and CT or radiography of the chest are standard preoperative investigations. A colonoscopy is performed if it has not been recently done. During surgery, manual exploration of the abdomen is performed, and intraoperative ultrasonography of the liver is commonly used to search for additional metastases. Despite this careful preoperative and intraoperative search for subclinical disease, most patients have recurrence after liver resection. Three-year survival rates after resection have ranged from 30% to 64%1–16 in reported series. In two of these series, hepatic arterial infusion pumps were inserted as part of the treatment in some patients. 12,16 In another series, only disease-free survival rates were noted. 6 Three-year overall survival rates in the other series ranged from 30% to 58% (Table 1); 5-year survival rates ranged from 16% to 45%. Recurrence was equally frequent in the liver and in extrahepatic sites. Therefore, a means of detecting disease not appreciated by current staging tools is a priority to reduce the frequency of futile resections.

Table 1. PUBLISHED SERIES OF LIVER RESECTIONS FOR METASTATIC COLORECTAL CARCINOMA PROVIDING 3-YEAR OVERALL SURVIVAL

Positron emission tomography (PET) with the radiolabeled glucose analog [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) is a sensitive diagnostic tool that images tumors based on increased uptake of glucose by tumor cells. Several recent publications have shown that FDG-PET is much more sensitive than CT in detecting colorectal cancer. Valk et al 17 reported on a group of 115 patients with recurrent colorectal cancer. The sensitivity and specificity for FDG-PET were 93% and 98%, respectively, compared with 69% and 96% for CT. Abdel-Nabi et al 18 reported sensitivities of 88% and 38% for the detection of colorectal metastases by FDG-PET and CT, respectively. Delbeke et al 19 found that FDG-PET was more sensitive than CT or CT portography for detecting intrahepatic and extrahepatic recurrences of colorectal cancer. We studied 58 patients with suspected recurrent or advanced primary colorectal cancer. The sensitivity and specificity of FDG-PET were 91% and 100%, respectively, for detecting local pelvic recurrence and 95% and 100% for hepatic metastases. By comparison, CT had a sensitivity and specificity of 52% and 80% for detecting pelvic recurrence and 74% and 85% for detecting hepatic metastases. 20 Fong et al 21 reported that FDG-PET directly altered management in 23% of patients with hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer being considered for liver resection. Several other centers have reported similar results. 22–24 We and others have also reported that FDG-PET often detects recurrent colorectal cancer in patients with increasing carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels and no evidence of recurrent disease on CT. 17,25 In all, patient management seems to be changed in approximately 25% of patients who undergo FDG-PET in addition to standard staging procedures.

These encouraging results suggest that FDG-PET might reduce or eliminate futile resections and lead to better outcomes after hepatic resections for metastatic colorectal tumors. However, no survival results have been reported for patients who have actually undergone liver resection after being staged by FDG-PET. The purpose of this report is to present such results from a single institution in which all patients with colorectal carcinoma metastases were staged by FDG-PET and entered into a prospective database.

METHODS

From April 1995 to February 1999, 43 patients with colorectal carcinoma metastatic to the liver were evaluated and were considered to have resectable disease after the completion of conventional staging. All patients underwent staging by abdominal CT and either chest radiography or CT scan. In a few patients, magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen was performed. In many instances, these investigations were performed in an outside institution, and when the CT scan was not recent or of acceptable quality, CT was repeated before FDG-PET. FDG-PET was performed in all patients. In a few cases of synchronous metastases, the presence of metastatic colorectal cancer in the liver was detected by examination of the liver at the time of resection of the colon primary rather than from information obtained by preoperative imaging.

All FDG-PET studies were performed at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University School of Medicine. The protocol has been described previously in detail. 20 Patients fasted for at least 4 hours before the study. To minimize interference from urinary tract activity, a urinary catheter was placed in the bladder, approximately 1,500 mL of 0.9% saline was infused intravenously, and 20 mg furosemide was administered intravenously 20 minutes after FDG administration (except when contraindicated). All studies were interpreted in routine clinical fashion by an experienced nuclear radiologist. PET images were interpreted by subjective visual assessment. In most instances, an antecedent CT scan or report was available to the radiologist at the time of FDG-PET interpretation. All imaging results were correlated with the subsequent final diagnosis, which was established by histology, by findings at surgery, or by at least 6 months of clinical observation from the time of FDG-PET.

In patients with disease deemed to be operable after FDG-PET, laparotomy and abdominal exploration, including intraoperative ultrasonography of the liver, were performed. Liver resection was then performed in patients still found to have operable disease. In three patients with synchronous metastases, the liver resection was performed at the same sitting as the resection of the colorectal primary.

Postoperative follow-up was performed at regular intervals after surgery. Serial CEA measurements and CT scans were performed. In some patients, FDG-PET was used in the postoperative period to search for residual tumor when this was suspected on the basis of other test results.

Analyses of overall survival and disease-free survival were performed by the Kaplan-Meier method using SAS version 7 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The 95% confidence limits of the means of the Kaplan-Meier estimates were also calculated.

RESULTS

The patient population consisted of 26 men and 17 women, ranging in age from 45 to 77 years (mean 61.2). The hepatic metastases were synchronous in 17 patients (40%). Synchronous lesions are defined as those discovered before resection of the primary colorectal cancer or during that procedure. In the remaining 26 patients (60%), the metastases were metachronous and were diagnosed from a few months to 7 years after resection of the primary tumor.

Investigations performed before FDG-PET identified one hepatic tumor in 28 patients, two to four tumors in 9 patients, and more than four tumors in 3 patients. Three patients who had an increasing CEA level did not have a tumor localized by CT. Four patients had concomitant single pulmonary metastases; in three of these there was a single hepatic lesion, and in the other patient there were two hepatic lesions.

By comparison with the conventional staging, FDG-PET identified additional disease in 10 patients (25%). In the three patients with an increasing CEA level and a negative CT scan, single hepatic lesions were found by FDG-PET. In another patient thought to have one hepatic lesion, a second true hepatic lesion was identified by PET. Surgical resection was not contraindicated by the new PET findings in these four patients, and resection was performed. In six patients, the disease newly identified by FDG-PET rendered the patients inoperable. In two patients each thought to have a single hepatic metastasis and a single pulmonary metastasis, additional disease was identified in the paraaortic nodes in one patient; in the other patient, five additional hepatic metastases involving both sides of the liver were discovered. In the other four patients, additional disease was identified in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic sites. Also, in four of these six patients it had been thought that metastases were confined to one hemiliver, but FDG-PET revealed bilateral disease. In one other patient, two lesions in the right hemiliver were reported on CT. Only one lesion was observed by FDG-PET and only one malignant lesion was present at surgery, the other tumor being focal nodular hyperplasia. Thus, overall, the findings on FDG-PET differed from those on CT in 11 of the 43 patients; in 6 of these, planned surgery was aborted directly as a result of the findings on FDG-PET.

FDG-PET did not detect all hepatic lesions. In five patients new lesions were found at surgery, by palpation in four patients and by intraoperative ultrasonography in one patient. Palpation resulted in detection of five lesions in four patients, ranging from 0.2 to 1.6 cm. Except for the smallest lesion, all these tumors were close to other larger lesions that had been detected by FDG-PET. It seems likely that these “twin” tumors in one hepatic segment appeared as single lesions on FDG-PET because of their proximity. Although FDG-PET was not completely accurate in these instances, the closeness of the twin tumors meant that the originally intended resection would encompass both tumors. In the other patient, intraoperative ultrasonography detected a metastasis 0.7 cm in diameter that was located in the right posterior section of the liver, away from two other lesions detected by FDG-PET. This finding changed the surgical strategy, and a larger resection was performed. Both FDG-PET and CT were negative in a patient who was known from laparotomy findings at the time of colon resection to have a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon with a hepatic metastasis, 0.9 cm in diameter. In two patients, tumors 0.4 cm and 0.7 cm in diameter were not detected by any means until the specimen was cut by the pathologist. These tumors were also close to known tumors. Therefore, except for the one patient who had an additional lesion discovered by intraoperative ultrasonography, the surgical strategy was not altered by false-negative PET findings in the liver.

Laparotomy was performed in 37 patients deemed to have resectable disease after preoperative staging, including FDG-PET. A single small metastatic peritoneal implant was found in each of two patients, one on the diaphragm and one on the intestine. Liver resection was aborted in these patients. No lesions were identified on intraoperative ultrasonography that prevented complete resection of the hepatic metastases. Liver resection was performed in 35 patients. Therefore, 95% of patients who had a laparotomy after staging by FDG-PET actually had resectable disease.

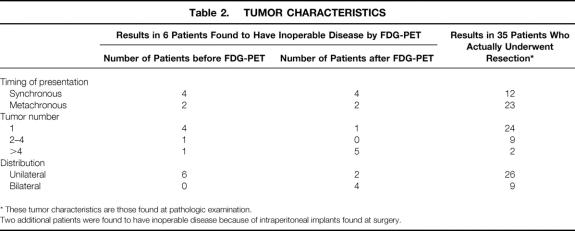

The tumor characteristics of the six patients whose procedure was canceled as a result of findings on FDG-PET and those of the 35 patients who had liver resection are shown in Table 2. The liver tumors of the patients who were eliminated were more often synchronous, bilateral, and multiple. These characteristics are known to be associated with a poorer prognosis after resection. Furthermore, five of the six patients were also found to have extrahepatic disease. In the 35 patients whose tumors were resected, the hepatic lesions were synchronous in 12 (34%) and metachronous in 23 (66%). Single lesions were present in 24 patients, including one patient with a single lung lesion resected at a separate procedure. Two to four lesions were treated in another nine patients, one of whom had a single lung lesion that also was resected at a separate procedure. Two patients had more than four lesions. In 26 of 35 patients, the tumor was confined to one hemiliver, although some tumors abutted the midplane of the liver. The largest lesion resected was 12.5 cm in diameter; the smallest was less than 1 cm.

Table 2. TUMOR CHARACTERISTICS

* These tumor characteristics are those found at pathologic examination.

Two additional patients were found to have inoperable disease because of intraperitoneal implants found at surgery.

Hemihepatectomy or extended hemihepatectomy was performed in 24 patients by the following techniques: right hemihepatectomy in 9 patients, left hemihepatectomy in 7 patients, and extended right hemihepatectomy in 8 patients. More localized resections were performed in 11 patients, and in 2 of these the resection was a nonanatomical wedge resection.

In 23 patients, the resection margin exceeded 1 cm, and in 12 it was less than 1cm. There were no patients with positive resection margins, but one patient was discovered to have a positive lymph node in the tissues adjacent to the specimen. There were no postoperative deaths (defined as any death before discharge or any death within 30 days whether still in the hospital).

The median length of follow-up since hepatic resection was 24 months (range 6 months to 4.5 years). Six patients died of disease recurrence 3, 6, 11, 11, 19, and 21 months after surgery. There were no other deaths. Cancer recurred in the liver, lung, and brain in four, three, and two patients, respectively, three patients having recurrence in two sites. Five of the six patients who died had poor prognostic factors at the time of resection. Two had multiple tumors (five and more than five), two had large tumors (9.5 and 12.5 cm in diameter), and one patient was discovered to have metastatic cancer in a lymph node adjacent to the resected liver.

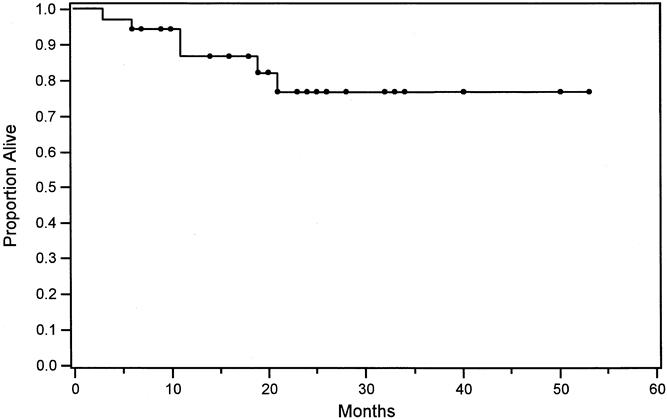

The Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival at 3 years for all patients who underwent resection was 77% (Fig. 1). The 95% confidence limits of the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 3-year survival were 60% to 94%. The lower confidence limit of 60% exceeded the mean Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival at 3 years from any previously reported comparable case series (see Table 1).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival in 35 patients undergoing liver resection after staging with positron emission tomography.

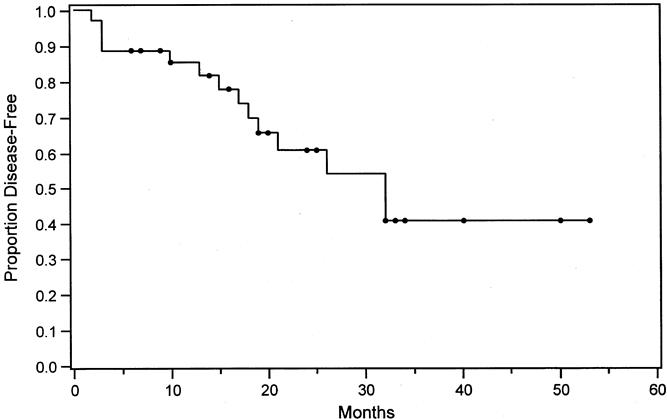

Eight patients who were still alive as of this writing had recurrence of cancer in the liver (n = 3), lung (n = 4), and bone (n = 2). One of these patients had recurrence in both the liver and lung. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of disease-free survival at 3 years was 40% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimate of disease-free survival in 35 patients undergoing liver resection after staging with positron emission tomography.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study is that the 3-year actuarial overall survival of patients screened by FDG-PET before liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer was very high, at 77%. This appears to be an improvement over past results. Comparison between this series and previously published series requires not only the results of 3-year overall survival but an estimate of how well these results represent the true or population results of patients undergoing resection with and without preoperative FDG-PET. To do this for patients screened by FDG-PET, we determined the 95% confidence limits of the 3-year survival for patients in this series. Based on those values, it can be said that the true or population result for patients screened by FDG-PET probably is at or above, but not below, 60%, the lower confidence limit of the estimate of 3-year survival. Confidence limits of survival estimates are rarely published and are not available for previously published series. However, there are many such case series, some with large numbers of patients (see Table 1). The 3-year overall survival results fluctuate from 30% to 58%, but most results cluster around 40%; the median result is actually 42.5%. Nine of the 12 case series reported 3-year survival results between 37% and 47%. The Registry series, with more than 800 patients, reported a 43% overall 3-year survival. 5 Therefore, a value of 40% to 45% is the best current estimate of the true value. The 3-year overall survival results are not related to year of publication (see Table 1), making it unlikely that a comparison between the results of the present series and the results of those previously published is biased by an improvement in results that has occurred gradually over time.

Two other case series have been reported in which many patients also underwent intraarterial chemotherapy with hepatic infusion pumps. 12,21 These showed 3-year overall survival rates of 57% and 64%, respectively. This therapy has recently been shown to prolong overall survival when used in combination with systemic adjuvant therapy after liver resection. 26 It was not used in our patients and is not therefore included in these tables.

The preceding analysis suggests that true 3-year survival results of patients undergoing liver resection without hepatic artery infusion pumps for colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver is approximately 45%, and that the comparable figure for patients screened by FDG-PET is at least 60%. The preceding analysis does not provide the certainty of a randomized comparison and cannot take its place, but it provides compelling evidence that FDG-PET can improve survival after liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver.

A subtle but important point is that the use of FDG-PET is not improving survival by itself, but is allowing surgical techniques to be applied with greater likelihood of benefit to patients. The result is better survival of patients who do undergo surgery because the target population for surgery has changed, rather than because FDG-PET and surgery produce longer survival times for the same sort of patients represented in previously published studies. There was no selection of patients entering this series: all patients referred were staged for resection as in the comparable trials. However, it appears that the patients who actually underwent laparotomy had fewer negative prognostic factors than did the patients who presented for staging. In other words, FDG-PET probably improves survival by changing the target population to one that has a better prognosis at the time of actual resection. This is in contrast to the use of adjuvant therapy with hepatic artery infusion pumps, which seems to be improving survival without changing the target population. 26

We calculated the 3-year disease-free survival rate, a value infrequently reported in case series of this type. Of those we have been able to find, the 3-year disease-free survival rate ranged from 15% to 28%5–7,11 as opposed to 40% for this series. Therefore, although FDG-PET is probably a valuable tool, most patients selected for surgery by FDG-PET will still have recurrence of disease because of the presence of disease that cannot be detected even by FDG-PET. It will be of interest to determine whether the use of adjuvant therapy with hepatic artery infusion pumps will have special relevance in this group of patients.

Another apparent advantage of PET is that it improves resectability rates. In our series, 95% of patients who underwent laparotomy actually underwent a hepatic resection. Again, it does so by changing the population of patients who undergo surgery rather than altering the disease, for instance by downstaging using neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Jarnagin et al 27 recently examined a large series of patients to investigate this point. In more than 400 patients who underwent exploration between 1992 and 1997, 21% were found to have unresectable disease at the time of surgery, largely because of the presence of unsuspected intrahepatic or extrahepatic metastases. By comparison, the 95% resectability rate in our series is similar to that achieved by John et al, 28 who used staging laparoscopy to detect unresectable tumors before laparotomy.

This study has shown once again that FDG-PET is limited by its poor sensitivity for detecting small lesions (<1 cm in diameter) and its inability to discriminate between lesions close to one another. Mucinous tumors are also less sensitively detected, as we recently reported. 29 In this study, the additional lesions detected at laparotomy prevented resection in only two patients.

In summary, FDG-PET appears capable of fulfilling its promise as a diagnostic tool that will improve patient selection and increase the overall survival rate after liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases. Although our results are encouraging, recurrence of tumor after liver resection will still be common if this is the only strategy. It is possible that the sensitivity of the technique can still be improved. Larger controlled trials are required to define more precisely the role and utility of PET in this clinical setting.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Kim Trinkaus for statistical assistance.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Dr. Steven M. Strasberg, Box 8109, Suite 17308 West Pavillion Tower, 1 Barnes Hospital Plaza, St. Louis, MO 63110.

E-mail: strasbergs@msnotes.wustl.edu

Accepted for publication August 30, 2000.

References

- 1.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg 1990; 77: 1241–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekberg H, Tranberg KG, Andersson R, et al. Determinants of survival in liver resection for colorectal secondaries. Br J Surg 1986; 73: 727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordlinger B, Quilichini MA, Parc R, et al. Hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Influence on survival of preoperative factors and surgery for recurrences in 80 patients. Ann Surg 1987; 205: 256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradpiece HA, Benjamin IS, Halevy A, et al. Major hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 1987; 74: 324–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resection of the liver for colorectal carcinoma metastases: a multi-institutional study of indications for resection. Registry of Hepatic Metastases. Surgery 1988; 103:278–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Schlag P, Hohenberger P, Herfarth C. Resection of liver metastases in colorectal cancer: competitive analysis of treatment results in synchronous versus metachronous metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 1990; 16: 360–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doci R, Gennari L, Bignami P, et al. One hundred patients with hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer treated by resection: analysis of prognostic determinants. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fegiz G, Ramacciato G, Gennari L, et al. Hepatic resections for colorectal metastases: the Italian multicenter experience. J Surg Oncol 1991; 2 (supp):144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Taswell HF, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and determinants of survival after liver resection for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 1992; 216: 493–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott S, Carty N, Anderson L, et al. Liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 1995; 21: 33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M, Forster J, Langer B, et al. A study of prognostic factors for hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Am J Surg 1997; 173: 467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jourdan JL, Cannan R, Stubbs R. Hepatic resection for metastases in colorectal carcinoma. NZ Med J 1999; 112: 91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins LT, Millikan KW, Bines SD, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Am Surg 1997; 63: 605–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakalakos EA, Kim JA, Young DC, et al. Determinants of survival following hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Surg 1998; 22: 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohlsson B, Stenram U, Tranberg KG. Resection of colorectal liver metastases: 25-year experience. World J Surg 1998; 22: 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valk PE, Abella-Columna E, Haseman MK, et al. Whole-body PET imaging with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in management of recurrent colorectal cancer. Arch Surg 1999; 134: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Nabi H, Doerr RJ, Lamonica DM, et al. Staging of primary colorectal carcinomas with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose whole-body PET: correlation with histopathologic and CT findings. Radiology 1998; 206: 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delbeke D, Vitola JV, Sandler MP, et al. Staging recurrent metastatic colorectal carcinoma with PET. J Nucl Med 1996; 38: 1196–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogunbiyi OA, Flanagan FL, Dehdashti F, et al. Detection of recurrent and metastatic colorectal cancer: comparison of positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Ann Surg Oncol 1997; 4: 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong Y, Saldinger PF, Akhurst T, et al. Utility of 18F-FDG positron emission tomography scanning on selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Am J Surg 1999; 178: 282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flamen P, Stroobants S, Van Cutsem E, et al. Additional value of whole-body positron emission tomography with fluorine-18–2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in recurrent colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitola JV, Delbeke D, Meranze SG, et al. Positron emission tomography with F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose to evaluate the results of hepatic chemoembolization. Cancer 1996; 78: 2216–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai DT, Fulham M, Stephen MS, et al. The role of whole-body positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in identifying operable colorectal cancer metastases to the liver. Arch Surg 1996; 131: 703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flanagan FL, Dehdashti F, Ogunbiyi OA, et al. Utility of FDG-PET for investigating unexplained plasma CEA elevation in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemeny N, Huang Y, Cohen AM, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of chemotherapy after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 2039–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, Ky A, et al. Liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: assessing the risk of occult irresectable disease. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 188: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.John TG, Greig JD, Crosbie JL, et al. Superior staging of liver tumors with laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 711–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger KL, Nicholson SA, Dehdashti F, et al. FDG-PET evaluation of mucinous neoplasms: correlation of FDG uptake with histopathologic features. Am J Roentgenol 2000; 174: 1005–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]