Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness and safety of low-dose unfractionated heparin and a low-molecular-weight heparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after colorectal surgery.

Methods

In a multicenter, double-blind trial, patients undergoing resection of part or all of the colon or rectum were randomized to receive, by subcutaneous injection, either calcium heparin 5,000 units every 8 hours or enoxaparin 40 mg once daily (plus two additional saline injections). Deep vein thrombosis was assessed by routine bilateral contrast venography performed between postoperative day 5 and 9, or earlier if clinically suspected.

Results

Nine hundred thirty-six randomized patients completed the protocol and had an adequate outcome assessment. The venous thromboembolism rates were the same in both groups. There were no deaths from pulmonary embolism or bleeding complications. Although the proportion of all bleeding events in the enoxaparin group was significantly greater than in the low-dose heparin group, the rates of major bleeding and reoperation for bleeding were not significantly different.

Conclusions

Both heparin 5,000 units subcutaneously every 8 hours and enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once daily provide highly effective and safe prophylaxis for patients undergoing colorectal surgery. However, given the current differences in cost, prophylaxis with low-dose heparin remains the preferred method at present.

There is evidence from clinical and autopsy studies that patients undergoing colorectal surgery are at high risk for developing postoperative venous thromboembolism. 1–13 In fact, their risk for venous thrombosis is among the highest of all general surgery patients. 1,2 Estimates from the control groups of randomized prophylaxis trials show that more than 30% of colorectal surgical patients develop postoperative deep venous thrombosis (DVT) compared with a risk of approximately 20% for all general surgery patients. 3–13 These patients are also at increased risk for developing pulmonary embolism (PE). 2,14 In a cohort of 19,161 patients, Huber et al 2 reported a fourfold greater incidence of symptomatic PE in patients undergoing colorectal surgery than in those having other general surgical procedures. Tongren 14 found fatal PE in 3.1% of colorectal surgery patients and in 0.8% of those having other abdominal surgical procedures.

Prophylaxis of DVT is recommended for patients undergoing general surgical procedures. 15–17 There is level 1 evidence that prophylaxis with low-dose heparin (LDH) reduces the incidence of both DVT and fatal PE. 17,18 In addition to its proven efficacy, LDH is inexpensive and easily administered. However, despite prophylaxis with LDH, approximately 10% to 15% of colorectal surgery patients have residual DVT, a rate twice that of all general surgery patients. 3–13

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) have several pharmacologic advantages over unfractionated heparin, including increased bioavailability, substantially reduced protein binding, and prolonged half-life, making once-daily dosing possible. 19 These agents also have decreased interactions with platelets, which may reduce the risk of bleeding and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. 19 Although LMWHs have been shown to have greater efficacy than LDH as prophylactic agents in high-risk patient groups, 17,20–22 they have not been shown to be superior to unfractionated heparin in meta-analyses of prophylactic use in general surgical patients. 20–22 However, most general surgery trials have included a high proportion of relatively low-risk patients, and therefore these results may not be applicable to the higher-risk colorectal patients. Further, there have been no randomized trials comparing LMWH and unfractionated heparin specifically in colorectal surgery patients.

The primary objective of this multicenter, randomized trial was to compare the efficacy of LDH and LMWH in a large group of colorectal surgical patients using contrast venography as the principal outcome measure. The second objective was to compare the safety of the two interventions.

METHODS

Patients and Study Design

This study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial conducted at 10 university hospitals in Canada. Adult patients undergoing surgery during which part or all of their colon or rectum was resected or in whom a complete rectal dissection was performed (e.g., for rectal prolapse) were potentially eligible for entry, provided the procedure was performed under general anesthesia and was at least 1 hour long. Patients were excluded if they required anticoagulant, antiinflammatory, or antiplatelet therapy that could not be discontinued; had hepatic or renal failure; had a history of a systemic bleeding diathesis or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, uncontrolled hypertension, hemorrhagic stroke or gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the previous 3 months, a major psychiatric disorder, or a systemic allergy to contrast material; or were pregnant or lactating. All study patients provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the ethics review board at each institution.

Before randomization, patients were stratified by institution, nature of the disease (benign or malignant), and the extent of the anticipated dissection (colonic or colorectal/rectal). A central, computer-generated randomization scheme in blocks of four was used to prepare numbered kits of study medication that were provided to the pharmacy departments of the study centers. In no case was the randomization code broken before final closure of the study.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to receive either calcium heparin 5,000 units subcutaneously every 8 hours or the LMWH enoxaparin 40 mg (100 antifactor Xa units per milligram; Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, Montreal, Canada) subcutaneously once daily in the morning plus two placebo injections of 0.9% saline daily to maintain the double-blind nature of the study. The study injections were prepared as 0.2-mL preloaded, consecutively numbered syringes. In both groups, prophylaxis was initiated 2 hours before surgery and one further injection (heparin or placebo) was given at 8 pm on the day of surgery. Thereafter, patients received three injections daily for up to 10 days. Other methods of pharmacologic or mechanical prophylaxis, including graduated compression stockings, were not allowed, nor was the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents.

Assessment of Outcomes

Patients were assessed daily to ensure compliance with the protocol and to review their clinical status. Hemoglobin and platelet counts were obtained daily. On or before postoperative day 9, patients underwent bilateral ascending contrast venography using 75 to 100 mL nonionic contrast for each limb to provide opacification of the deep veins of the calf, thigh, and pelvis, including the common iliac veins. Acute venous thrombosis was defined as a constant intraluminal filling defect in a deep leg vein seen on two or more views or an abrupt cut-off of contrast in a vein associated with absent or poorly developed collaterals. Proximal DVT was defined as thrombosis involving the popliteal or more proximal veins. Bilateral duplex compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity veins (including, if technically possible, the pelvic veins and the femoral and popliteal veins to the calf vein trifurcation) was also obtained on the same day as, but before, venography. The ultrasound criterion for venous thrombosis was noncompressibility of all or part of a proximal deep vein. Although ultrasonography was performed, the results of the venography were used for the outcome assessment.

If DVT was clinically suspected before day 9, the patient underwent duplex ultrasonography, followed by venography if the results were positive. 23,24 Patients with clinical features suggestive of PE underwent ventilation-perfusion lung scanning, followed if necessary by venous ultrasonography, contrast venography, pulmonary angiography, or a combination of these using a prespecified investigation algorithm. A diagnosis of PE was based on the presence of suggestive symptoms and a high-probability lung scan, positive pulmonary angiogram, or the presence of DVT if the lung scan was nondiagnostic.

The primary outcome measure was objectively confirmed venous thromboembolism (DVT or PE). All venograms and other imaging studies for venous thromboembolism were reviewed by a central adjudication committee consisting of two vascular radiologists and a thromboembolism consultant. They were unaware of the treatment allocation and used a detailed coding form and prespecified criteria.

Intraoperative blood loss was recorded from sponge weights and suction aspirates. Blood loss through drains and transfusion requirements were also documented. Postoperative bleeding was classified as major or minor. Major bleeding was defined as intracranial, retroperitoneal, or clinically overt hemorrhage associated with a decrease in the hemoglobin level of more than 20 g/L, the transfusion of 2 or more units of packed cells, or the need for surgical intervention. Minor bleeding included ecchymosis of more than 10 cm, wound hematoma extending more than 5 cm from the incision, unexpected macroscopic rectal bleeding or hematuria, epistaxis of more than 5 minutes duration, or bleeding from other sites associated with a decrease in the hemoglobin level of less than 20 g/L. All bleeding events were adjudicated centrally by a committee of principal investigators who were unaware of the treatment allocation.

Study data were entered into a computerized database at each center and then transferred electronically to the central data collection center. The analysis was performed independent of the sponsor at the Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Mount Sinai Hospital, Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute.

Sample Size Calculation

Before commencing the study, we estimated that the risk of venous thromboembolism in the LDH group would be 12.5%. With a type 1 error of 0.05 (two-tailed) and a power of 0.80, it was determined that 470 patients with adequate outcomes per group would give sufficient power to detect an absolute difference between the groups of 5.5%. 25

Statistical Analysis

All patients who had an eligible surgical procedure and adequate venography or documented PE were included in the analysis for thromboembolism. All randomized patients, except those who did not fulfill the entry criteria, were included in the analysis of blood loss and bleeding events.

The baseline comparability of the treatment groups and comparisons of outcomes were tested using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test for proportions and the Student t test for continuous data. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) for the differences in two proportions were calculated using exact methods when possible and asymptotic methods otherwise. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATXACT for Windows (Cytel Software Corp., Cambridge, MA).

RESULTS

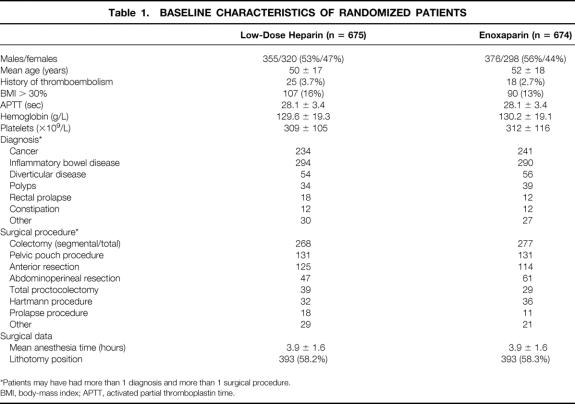

During the study period, 2,490 patients underwent colorectal surgical procedures at the participating institutions. There were 2,354 patients (94.5%) eligible for entry; of these, 1,349 (57.3%) agreed to participate. The characteristics of the two treatment groups were similar (Table 1).

Table 1. BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF RANDOMIZED PATIENTS

*Patients may have had more than 1 diagnosis and more than 1 surgical procedure.

BMI, body-mass index; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time.

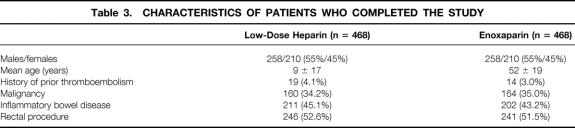

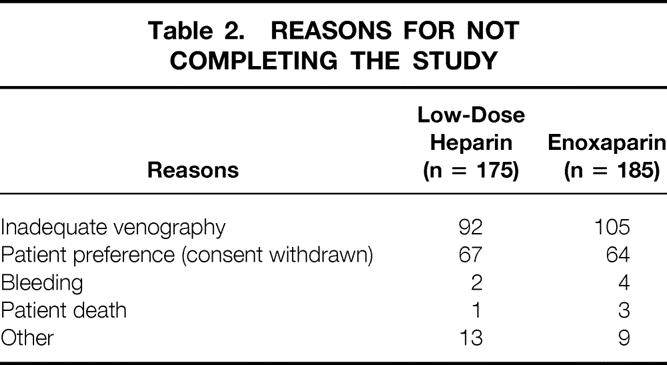

Fifty-three patients (3.9%) (32 in the LDH group, 21 in the LMWH group) were excluded from analysis because they were subsequently found to be ineligible: surgery was canceled in 5 patients, a colonic or rectal resection was not performed in 43, and 5 patients had a history of allergy to contrast. An additional 360 patients (26.7%) did not complete the study for the reasons listed in Table 2. Of the 360 patients, the masked outcomes adjudication committee concluded that 197 patients had venograms that were not adequate for proving or excluding DVT. Four patients died; the cause of death in all four was myocardial infarction. Thus, 936 patients (69.4%) who met the inclusion criteria and successfully completed the study were included in the efficacy analysis. The two groups were well balanced for demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 3).

Table 2. REASONS FOR NOT COMPLETING THE STUDY

Table 3. CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WHO COMPLETED THE STUDY

Compliance in both groups was high. Only 4 of 468 LDH patients and 5 of 468 LMWH patients failed to receive a preoperative dose of study drug. Subsequently, only three and six patients in the two groups, respectively, missed two consecutive or more than three doses of study medication during the study period.

Thromboembolic Events

The venous thromboembolism rate was the same in both groups: 44/468, or 9.4% (95% CI of the difference, 0 ± 3.7%). Of these, five were symptomatic (three in the LDH group, two in the LMWH group). The rate of proximal DVT was 2.6% in the LDH group and 2.8% in the LMWH group. No instances of isolated iliac vein thrombosis were identified by venography or ultrasonography. Only one enoxaparin patient had a symptomatic, nonfatal PE. There were no deaths attributable to thromboembolism.

Patients with a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease who were randomized to LDH had a significantly lower rate of thromboembolism than those receiving LMWH (2.9% vs. 9.0%, P = .037). Obese patients (body-mass index > 30%) receiving LDH had a significantly greater rate of thromboembolism (26.3% vs. 9.4%, P = .001). There were no significant differences in the effectiveness of LDH and LMWH in patients with cancer (16.9% vs. 13.9%, P = .052), in patients older than 50 years (12.4% vs. 13.2%, P = .79), in patients with a history of thromboembolism (31.5% vs. 35.7%, P = 1.0), or in patients undergoing a rectal dissection (8.0% vs. 9.5%, P = .60).

Of the 360 patients who did not complete the study with adequate venography, 237 (65.8%) had bilateral duplex ultrasonography performed between day 5 and 9. No patient in the LDH group but two in the LMWH group had evidence of DVT using this noninvasive test.

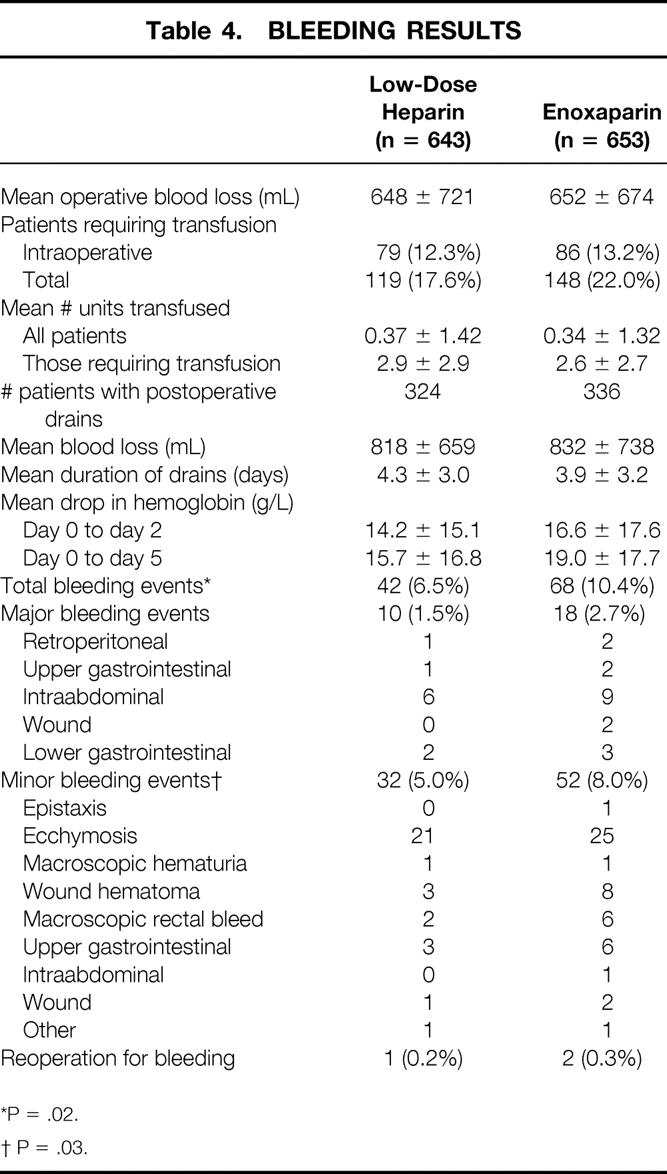

Bleeding Complications and Thrombocytopenia

Intraoperative and postoperative blood loss, transfusion requirements, and hemorrhagic complications are shown in Table 4. The mean intraoperative and postoperative blood loss, the mean number of units of blood transfused, and the proportion of patients requiring transfusions were similar in both groups. The total bleeding event rate was significantly lower in the LDH group than in the LMWH group (6.2% vs. 10.1%, P = .003), primarily because of an excess of minor bleeding episodes in the LMWH patients (P = .03). The rate of major bleeding events was also increased, but not significantly (1.5% vs. 2.7%, 95% CI difference −0.4–2.8%, P = .136). Overall, only three patients required reoperation for bleeding, and no patient died of a bleeding complication. Thrombocytopenia, defined as a 50% or greater drop in platelet count after postoperative day 5, occurred in six patients (0.9%) in each group.

Table 4. BLEEDING RESULTS

*P = .02.

† P = .03.

DISCUSSION

Among general surgery patients, those undergoing colorectal surgical procedures are at a higher-than-average risk for developing postoperative DVT because these procedures tend to be prolonged, patients are often placed in stirrups in the lithotomy position, and a pelvic dissection is commonly performed. Further, the indication for surgery is often cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and these are known to be risk factors for thromboembolism. 26,27 Because of the demonstrated greater efficacy of LMWH versus LDH in high-risk patients, including those having elective orthopedic surgery, we hypothesized that patients undergoing colorectal procedures might benefit from LMWH prophylaxis. 17,20–22 However, our results demonstrated equivalent efficacy both for all DVTs and for the clinically more important proximal thrombi. One possible explanation for this lack of difference between interventions may be the relatively high doses of both the unfractionated heparin (15,000 U daily) and the LMWH (4,000 anti-Xa U daily) used in our trial.

Our results reflect those of previous trials in general surgical patients that have failed to show that LMWH is significantly more effective than LDH. 17,20–22 The event rate was higher in this study (9.4%) than in many other large general surgery trials, 20–22,28–30 probably reflecting the higher thromboembolic rate in colorectal patients as well as our use of contrast venography as the routine test for DVT rather than fibrinogen leg scanning, which has been used in other studies. 31 In orthopedic studies, fibrinogen leg scanning has poor sensitivity for the detection of proximal DVT. 32 In general surgery trials, fibrinogen leg scanning is also likely to lack sensitivity and has been shown to have low specificity, with a false-positive rate of 29% in five studies in which positive leg scans were followed up by confirmatory venography. 28,33–35 Similarly, Doppler ultrasound is less sensitive than venography. In this study, only 5 of the 88 DVTs (5.6%) detected by venography were detected by ultrasonography. There were no DVTs detected by ultrasonography that were not detected with venography.

Only three previous general surgery trials used venography as the primary outcome measure. 36–38 Bounameaux et al 36 compared two LMWHs given once daily to 194 abdominal surgery patients who also used elastic stockings. The venographically proven DVT rate among the patients who received dalteparin 2,500 IU once daily was 32%; the rate in the patients who received nadroparin 3,075 IU was 16%. Both doses were substantially lower than the dose of enoxaparin used in our trial. In the study by Wiig et al, 37 DVT was demonstrated by routine venography in 27% of patients undergoing abdominal surgery who received enoxaparin 20 mg/day. After an interim analysis, the dosage of enoxaparin was increased to 40 mg/day and the observed DVT rate was 12% in cancer patients, supporting the importance of an adequate dose of prophylaxis in these patients. The ENOXACAN study also randomized general surgery patients to LDH 5,000 U three times daily or enoxaparin 40 mg/day, both commencing before surgery, and used routine venography as the primary outcome measure. 38 This study included only patients who underwent elective, potentially curative abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer. Patients in this study were considerably older on average than those in the present study (mean ages 68 vs. 50 years). The DVT rate in the ENOXACAN study was 18.2% in the LDH group and 14.7% in the enoxaparin group. These rates are similar to those in our study, where the overall thromboembolic event rate in patients with cancer was 15.5%.

Although venography has greater accuracy than fibrinogen leg scanning, obtaining a diagnostic study is impossible in 10% to 30% of patients, particularly when the DVT rates are low. In the ENOXACAN study, 40% of patients had inadequate venography. In our study, only 18% of patients had inadequate venography, and overall 69.4% were included in the efficacy analysis. The proportion of patients with inadequate venography was similar in both groups, and therefore the relative efficacy of the interventions should be unbiased. 39 In addition, bilateral ultrasonography was performed in 237 of the patients who did not have venography. Thus, overall 93.9% of randomized patients were evaluated for DVT by at least one objective screening modality.

In our study, there were significantly more bleeding events in patients receiving LMWH. The minor bleeding event rate was significantly increased, although the difference in the rate of major bleeding events was not significant. A similar trend was observed in the ENOXACAN study: major bleeding was seen in 4.1% of patients receiving enoxaparin and 2.9% of those receiving LDH. However, previous meta-analyses have not observed increased bleeding with LMWH in general surgery patients. 20,22,40 Palmer et al, 40 summarizing the results of 33 general surgical trials that compared LDH and LMWH, found significantly lower risk of bleeding in patients randomized to LMWH (relative ratio = 0.75, 95% CI 0.64–0.88). The meta-analysis by Koch et al 20 found that in general surgery trials comparing LDH with high-dose LMWH (>3,4000 U/day), the bleeding rates were greater in the LMWH patients (7.9% vs. 5.3%), whereas at lower doses of LMWH the reverse was true (3.8% vs. 5.4%). In the present trial, both minor and major bleeding rates were lower than those reported previously. In the ENOXACAN study, 38 the overall bleeding rates were 18.7% in the LMWH group and 17.1% in the LDH group. Cohen et al 41 reported that in a randomized controlled trial comparing LMWH and LDH, 8% of 3,809 patients undergoing abdominal surgery had major bleeding and 2% required reoperation. In the present trial, only 2.5% of patients in the LMWH group and 1.2% in the LDH group had a major bleeding event, and only three patients (0.2%) required reoperation for bleeding.

In summary, LMWHs have been advocated for prophylaxis in surgical patients because they are potentially more effective and safer, and with once-daily dosing they are more convenient to administer. In this study, we showed that LDH and LMWH are equally effective for the prevention of thromboembolism in colorectal surgery patients. The lack of superiority in thromboprophylaxis of LMWH over LDH has also been demonstrated among general surgery patients in other, smaller trials as well as in several meta-analyses. 20,22,40 Our results also showed greater bleeding rates with LMWH, although the risk of major bleeding was not significantly increased. Other considerations in deciding which prophylaxis regimen to use are the cost of treatment and the ease of administration. LMWH has the advantage of once-daily dosing versus two or three daily injections for LDH. However, currently in North America, the costs of the LMWHs are substantially higher than for unfractionated heparin. Our group has performed an economic analysis based on the results of the trial using both Canadian and American costs. 42 Not surprisingly, given the efficacy and safety results of this trial, the strategy of prophylaxis with LDH was the more cost-effective option. A strategy of enoxaparin prophylaxis was associated with equal numbers of symptomatic DVTs and PEs and an excess of 12 major bleeding episodes for every 1,000 patients treated, with an additional cost of $86,050 (Canadian data) or $145,667 (U.S. data). Even when sensitivity analyses were performed using optimal assumptions for the efficacy and safety of enoxaparin, the model favored LDH.

In conclusion, our results showed that in patients undergoing major colorectal surgical procedures, thromboprophylaxis with LDH is as efficacious and safe as that with LMWH. Given the differences in cost, prophylaxis with LDH remains the preferred method at present.

INVESTIGATORS

Coordinating Committee: McLeod RS, Geerts WH, Greenwood C, Sniderman KW, Wilson SR; Statistical Analysis: Greenwood C; Venography Adjudication: Sniderman KW, Geerts WH, Jaffer NM, Hynes DM, Fong K, Common A;

Mount Sinai Hospital (Toronto): McLeod RS, O’Connor B, Jaffer N, Salem S; St. Boniface General Hospital (Winnipeg): Silverman R, Carr V, McGinn G, Askew G; St. Francois d’Assise Hospital (Quebec): Gregoire R, Rousseau L, Dionne G, Rioux M; St. Joseph’s Health Centre (Toronto): Burul C, Sinclair J, Hynes D, Leekam R; St. Joseph’s Hospital (London): Taylor B, Moyer L, Bennett J, Dawson W; St. Michael’s Hospital (Toronto): Burnstein M, McDermott G, Common A, Campbell J; St. Paul’s Hospital (Vancouver): Atkinson K, Forshaw S, Marsh I, Wong T; Toronto General Hospital (Toronto): Marshall J, Foster D, Sniderman K, Wilson S Victoria General Hospital (Halifax): Anderson D, Grant B, Campbell RM; Women’s College Hospital (Toronto): Ross T, Coates D, Fong K; Anti-Xa Levels: Leclerc J, Lipman M; Economic Analysis: Etchells E, Detsky A.

References

- 1.Aberg M, Nilsson IM. Fibrinolytic activity of the vein wall after surgery. Br J Surg 1978; 65: 259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huber O, Bounameaux H, Borst F, Rochner A. Postoperative pulmonary embolism after hospital discharge. An underestimated risk. Arch Surg 1992; 127: 310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams HT. Prevention of postoperative deep vein thrombosis with perioperative subcutaneous heparin. Lancet 1971; 2: 950–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakkar VV, Spindler J, Klute PT, et al. Efficacy of low doses of heparin in prevention of deep vein thrombosis after major surgery. A double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaides AN, Kakkar VV, Field ES, et al. Optimal electrical stimulus for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. Br Med J 1972; 3: 756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallus AS, Hirsh J, Tuttle RJ, et al. Small subcutaneous doses of heparin in prevention of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med 1973; 288: 545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahnborg G, Friman L, Bergstrom K, et al. Effect of low-dose heparin on incidence of postoperative pulmonary embolism detected by photoscanning. Lancet 1974; 1: 329–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covey TH, Sherman L, Baue AE. Low-dose heparin in postoperative patients. A prospective coded study. Arch Surg 1975; 110: 1021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strand L, Bank-Mikkelsen OK, Lindewald H. Small heparin doses as prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis in major surgery. Acta Chir Scand 1975; 141: 624–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallus AS, Hirsh J, O’Brien SE, et al. Prevention of venous thrombosis with small subcutaneous doses of heparin. JAMA 1976; 235: 1980–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joffe S. Drug prevention of postoperative deep vein thrombosis. A comparative study of calcium heparinate and sodium pentosan polysulfate. Arch Surg 1976; 3: 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tongren S, Forsberg K. Concentrated or diluted heparin prophylaxis of postoperative deep venous thrombosis. Acta Chir Scand 1978; 144: 283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergqvist D, Hallbrook T. Prophylaxis of postoperative venous thrombosis in a controlled trial comparing dextran 70 and low-dose heparin. World J Surg 1980; 4: 239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tongren S. Pulmonary embolism and postoperative death. Acta Chir Scand 1983; 149: 269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins R, Scrimgeour A, Yusuf S, et al. Reduction in fatal pulmonary embolism and venous thrombosis by perioperative administration of subcutaneous heparin. Overview of results of randomized trials in general, orthopedic, and urologic surgery. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 1162–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) Consensus Group. Risk of and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. Br Med J 1992; 305: 567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clagett GP, Anderson FA, Geerts W, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 1998; 114 (suppl): S531–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bick RL, Haas SK. International Consensus Recommendations. Summary statement and additional suggested guidelines. Med Clin North Am 1998; 82: 613–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weitz JI. Low-molecular-weight heparins. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch A, Bouges S, Ziegler S, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin and unfractionated heparin in thrombosis prophylaxis after major surgical intervention: update of previous meta-analyses. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 750–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leicorovicz A, Haugh MC, Chapuis FR, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin in prevention of perioperative thrombosis. Br Med J 1992; 305: 913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nurmohamed MT, Rosendall FR, Buller HR, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard heparin in general and orthopaedic surgery: a meta-analysis. Lancet 1992; 340: 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koopman MM, van Beek EJ, ten Cate JW. Diagnosis of deep vein thromosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1994; 37: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearon C, Julian JA, Math M, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128: 663–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates & proportions. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981.

- 26.Kakkar VV, Howe CT, Nicolaides AN, et al. Deep vein thrombosis of the leg. Is there a “high-risk” group? Am J Surg 1970; 120: 527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talbot RW, Heppell J, Dozois R, et al. Vascular complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1986; 61: 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurmohamed MT, Verhaeghe R, Haas S, et al. A comparative trial of low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin) versus standard heparin for the prophylaxis of postoperative deep vein thrombosis in general surgery. Am J Surg 1995; 169: 567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergqvist D, Burmark US, Frisell J, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin once daily compared with conventional low-dose heparin twice daily. A prospective double-blind multicentre trial on preventing post-operative thrombosis. Br J Surg 1986; 3: 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leizorovicz A, Picolet H, Peyrieux JC, et al. Prevention of perioperative deep vein thrombosis in general surgery: a multicentre double-blind study comparing two doses of Logiparin and standard heparin. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lensing AW, Hirsh J. 125I-fibrinogen leg scanning: reassessment of its role for the diagnosis of venous thrombosis in post-operative patients. Thromb Haemost 1993; 69: 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agnelli G, Radicchia S, Nenci GG. Diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis in asymptomatic high-risk patients. Haemostasis 1995; 25: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koppenhagen K, Adolf J, Matthes M, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin and prevention of postoperative thrombosis in abdominal surgery. Thromb Haemost 1992; 67: 627–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallus A, Cade J, Ockleford P, et al. Organon (Org 10172) or heparin for preventing venous thrombosis after elective surgery for malignant disease? A double-blind, randomised, multicentre comparison. Thromb Haemost 1993; 70: 562–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergqvist D, Burmark US, Flordal PA, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin started before surgery as prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis: 2500 versus 5000 XaI units in 2070 patients. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bounameaux H, Huber O, Ebrahim K, et al. Unexpectedly high rate of phlebographic deep venous thrombosis following elective general abdominal surgery among patients given prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 326–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiig JN, Solhaug JH, Bilberg T, et al. Prophylaxis of venographically diagnosed deep vein thrombosis in gastrointestinal surgery. Multicentre trials 20 mg. and 40 mg. enoxaparin versus dextran. Eur J Surg 1995; 161: 663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ENOXACAN Study Group. Efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for prevention of deep vein thrombosis in elective cancer surgery: a double-blind randomized multicentre trial with venographic assessment. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1099–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodgers A, MacMahon S. Systemic underestimation of treatment effects as a result of diagnostic test inaccuracy: implications for the interpretation and design of thromboprophylaxis trials. Thromb Haemost 1995; 73: 167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer AJ, Schramm W, Kirchhof B, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin and unfractionated heparin for prevention of thromboembolism in general surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Haemostasis 1997; 27: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen AT, Wagner MB, Mohammed MS. Risk factors for bleeding in major surgery using heparin thromboprophylaxis. Am J Surg 1997; 174: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etchells E, McLeod RS, Geerts W, et al. Economic analysis of low-dose heparin vs. the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after colorectal surgery. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from Rhône-Poulenc Rorer Canada Inc.

Correspondence: Dr. Robin McLeod, Suite 449, 600 University Ave,, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5G 1X5.

E-mail: rmcleod@mtsinai.on.ca

Accepted for publication August 31, 2000.