Abstract

Objective

To examine the relation of financial status and demographics to the outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) in the public hospital setting.

Summary Background Data

Coronary artery bypass surgery is one of the most expensive and frequently performed surgical procedures in the United States. Considerable controversy surrounds the accessibility to quality cardiac care of indigent and minority populations. This study examines the hypothesis that demographics rather than access to care and economics influences outcomes in CABG.

Methods

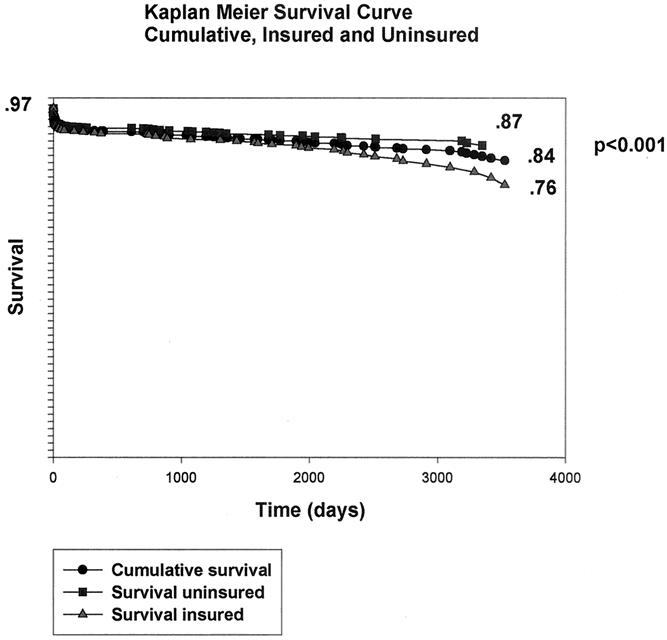

A retrospective review of 1,556 charts of patients who underwent CABG at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, a public hospital, during a 10-year period was performed. The parameters analyzed included sex, age, race, education, ejection fraction, comorbidities, surgical parameters, economics, complications, and cost of care. Comparisons were made between the insured and uninsured groups. Univariate statistical analysis was used to assess differences between groups. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were also generated.

Results

Two thirds of the patients were uninsured. The mean age of the uninsured patients was significantly lower than that of the insured patients. Ejection fractions were comparable. Comorbidities were similar, with a greater percentage of tobacco use in the uninsured population. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that the uninsured group had better overall survival and that the insured group manifested an increased rate of late death.

Conclusions

The financially challenged population appears to present for treatment earlier in life with coronary artery disease. Risk factors between the two groups were similar, except that tobacco use appears to be a significant problem in the disadvantaged population. The disease severity in both populations appeared to be similar; however, the uninsured patients had equivalent early survival with better late survival. Access to care in both groups was equal. In the public hospital setting for the disease state described, the financially challenged are afforded access to the current treatment technology with quality results.

The variations in use and access to medical care and procedures have become the focus of increasing concern from both the public and governmental agencies. It has been reported that lack of health insurance is associated with limited access to medical care, documented by fewer physician visits in the uninsured population, 1–4 and that medical care is delayed or forgone in these patients when serious symptoms occur. 5–7 The lack of medical insurance coverage appears to be associated with a lower access to recommended preventive services, 8,9 an increase in potentially avoidable hospital admissions, 10,11 increased acuity of illness on admission, 12,13 and less access to invasive procedures and technologically advanced treatment. 14,15

An increase in adverse medical outcomes in the newborn population has been associated with the lack of health coverage. 16 In patients who have lost health insurance because of health status or employment transition, studies have shown a measurable decline in health status. 17–19 In the Rand Health Insurance Experiment, financial payments in the form of copayments served as significant barriers to access and resulted in clinically important adverse outcomes. 20,21

Most studies have focused on the poor, insinuating that low income is associated with poor health, limited education, and limited access to healthcare. 22–24 No attempt was made to separate the poor from the uninsured in these studies. Two studies analyzed the relation between insurance and death rate; however, no stratification was performed for disease processes, preexisting conditions, or geographic access to care in the various age groups. 25,26

Recent studies focusing on the access to cardiac services, including coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), have shown that blacks, Latinos, the poor, and the uninsured undergo fewer such procedures than white and insured patients. 27–33 These differences have been attributed to overuse among the paying population and underuse in the disadvantaged setting. 34 Because of the limitations of these studies and the high-profile nature and expense of CABG, we undertook this study to determine outcomes in the uninsured and insured populations for this procedure. The hypothesis we examined was that demographics rather than access to care and economics influences outcomes in CABG.

METHODS

Data Collection

A retrospective chart review of patients undergoing CABG at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport, a public hospital, from 1990 to 2000 was performed. The data abstracted from the medical records included age, gender, ethnicity, insurance status, ejection fraction, comorbidities, complications, and survival. To verify educational status and death rate, attempts were made to contact by telephone all the patients in the study for the entire 10-year period. Contact was made with 86% of each study population at the 10-year point. The uninsured were more difficult to contact, primarily because of lack of direct telephone service. In those instances, family members were contacted and messages left for the subject to call the study center.

Data Analysis

The primary outcome of interest was survival for the uninsured and insured groups with respect to the surgical procedure. Only patients who underwent CABG were included in the study. Stratification for these two groups was performed with respect to the other variables tracked. The results were analyzed for statistical significance using one-way analysis of variance, with the appropriate ad hoc tests performed if statistical significance in the data was noted. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated for the uninsured and insured groups and compared with each other as well as the study population as a whole.

RESULTS

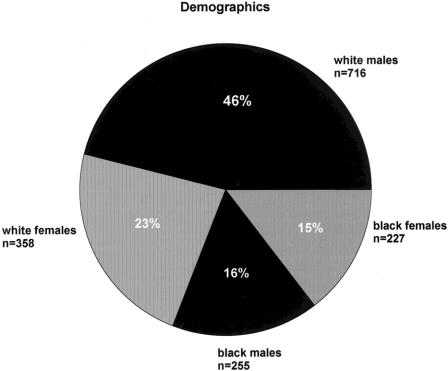

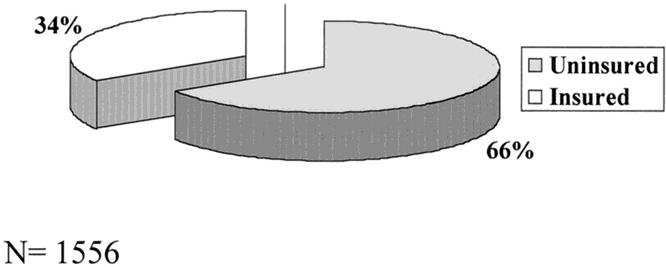

A total of 1,556 charts were reviewed. The population included 716 white men (46%), 358 white women (23%), 255 black men (16%), and 227 black women (15%), (Fig. 1). Sixty-six percent of the study population was uninsured (Fig. 2). The uninsured cohort consisted of 482 white men (47%), 260 white women (25%), 161 black men (16%), and 127 black women (12%). The insured population maintained some form of entitlement coverage: Medicare or Medicare HMO (70%), Medicaid (23%), or some form of indemnity coverage (7%).

Figure 1. Demographic distribution of the study population.

Figure 2. The distribution of the study population with and without health insurance.

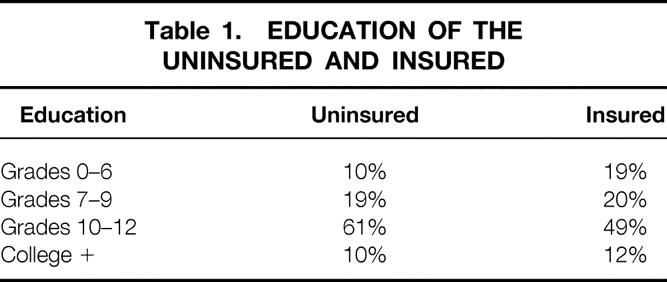

The age difference between the two groups was statistically significant. The mean age was 55 years for the uninsured patients versus 65 years for the insured (P < .001). The ejection fraction in the two groups was comparable at 63% for the uninsured and 57% for the insured. The educational level of the insured and uninsured was similar in both groups (Table 1). A greater proportion of the uninsured had a high school education (10% more), whereas the insured has a slightly higher percentage of college-educated members.

Table 1. EDUCATION OF THE UNINSURED AND INSURED

When comorbidities were examined as independent variables, no one particular disease state prevailed in either population. The incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia was equivalent in both groups. Smoking was more prevalent in the uninsured, but not to a significant degree.

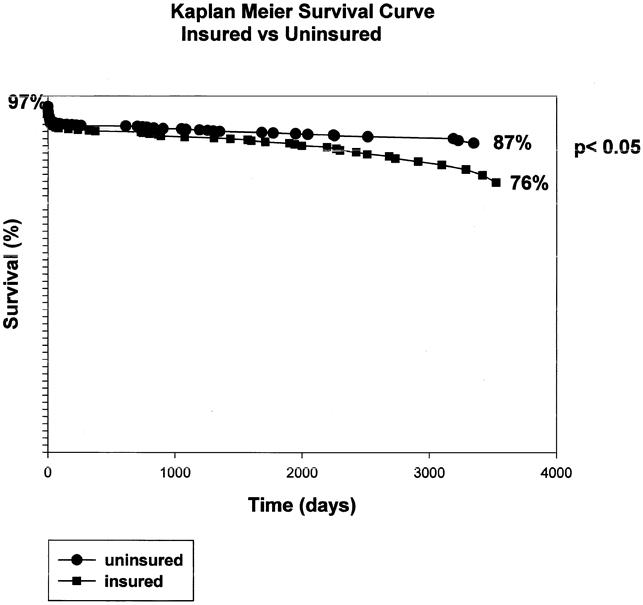

Figure 3 shows the relation between insurance status and 10-year survival. The uninsured had an 87% 10-year survival by Kaplan-Meier analysis. These survival data were statistically significant between the two groups (P < .05). When the two groups were independently compared with the overall study population survival, the uninsured had significantly better survival than the entire patient cohort or the insured group (P < .001) (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, the insured group had a significant rate of late death compared with the uninsured (P < .001).

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier survival curves for the uninsured versus the insured population undergoing CABG. The uninsured demonstrated a statistically significant increase in survival over the other group.

Figure 4. Overall survival for the entire study population. Of note is the late survival of 76% in the insured group.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the first assessment of the survival of patients undergoing CABG in relation to payor status. White men represented most of the uninsured population, with black patients representing a minority of the cohort. Our data are consistent with other published studies regarding the use of technical procedures in minority populations. 27,28 The exact cause of these proportions cannot be determined from this retrospective review because the surgical event had occurred. Whether these results indicate a failure in diagnosis and referral of these patients, an underuse of the procedure, or a failure of these patients to seek medical attention is purely speculative.

Most of the population had no form of health insurance coverage. Most of this population was white and male. These data are not consistent with previous reports indicating that most of the uninsured are ethnic minorities. 5 These differences may represent regional variations in the availability of jobs that provide insurance coverage or personal preference regarding the affordability of health coverage, because most of the population examined was employed in some capacity. The insured population was characterized by some form of entitlement program, be it Medicare, Medicare HMO, or Medicaid. Indemnity or private insurance was found in only 7% of the study population. This finding is reflected in the older age of the insured group. The public nature of the hospital examined may have contributed to this particular patient grouping.

The significant difference in the ages between the two groups would imply that the uninsured present earlier for treatment of coronary artery disease. The question arises whether the disease develops sooner in these patients or whether this group indeed availed themselves of the public hospital facilities earlier. The latter postulate is supported by the similarity in ejection fraction between the two groups. These data contradict previous studies indicating that the uninsured delay seeking medical attention and that their medical illness is more severe at the time of presentation. 7,12

Our data do not support the contention that the uninsured are less educated. 21 Our study groups demonstrated similar education levels. Whether education was related to income was not assessed in this patient cohort.

Diabetes, hypertension, and smoking prevailed in both groups, although there were no significant differences. Smoking appeared to be more prevalent in the uninsured, whereas the incidence of hypertension and diabetes was higher in the insured. The low incidence of hypercholesterolemia may reflect an ineffective screening method for the process.

The uninsured had significantly better survival than the insured after 10 years. This may be due to the younger age of the indigent population presenting for treatment at our facility. It is also obvious that at the 10-year follow-up point, this population is younger and therefore less likely to fall victim to other fatal disease processes prevalent in the older age groups. The insured group was older and the rate of late death was significantly greater, mainly as a result of other disease processes, particularly cancers. These data are not consistent with the contention that the absence of health insurance is necessarily related to a higher death rate. 26

Several limitations are inherent in this study. The retrospective nature of the data carries certain inherent biases. Adverse patient selection can be a factor in these studies as a result of facility bias. The fact that the institution is public, with a mandate to accept all patients regardless of status, influences the population mix. The data collected dealt with therapy after diagnosis. This limitation excludes the possibility of discerning whether diagnostic selection played a role in the outcomes presented.

Well-founded studies support the hypotheses that lack of health insurance may be correlated with limited access to care, increased use once the care is found or sought because the clinical condition is severe, and poorer outcomes. 6,13,26 These contentions are supported within the context of the studies presented. However, most of these studies deal with public health issues. Generalizing these conclusions to all disease states may be premature. This study represents the first attempt to analyze outcomes of the uninsured with respect to CABG. Our results clearly show that the uninsured who undergo CABG in a public hospital setting enjoy similar if not better survival than the insured in our region. It also indicates that analysis of outcomes with respect to healthcare coverage may need to be stratified according to disease process rather than generalized from public health data.

Discussion

DR. ROBERT M. MENTZER, JR. (Lexington, Kentucky): I congratulate Dr. Mancini for her fine presentation and the opportunity to review her manuscript in advance. She addresses a most controversial subject, and in doing so provides data that support her contention that the absence of health insurance does not necessarily relate to a higher mortality rate in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery.

In addition to her presentation, the conclusions expressed in the manuscript strongly contradict views that are generally expressed by epidemiologists and ultimately implemented by health care policy planners. For example, she emphasizes that at LSU-Shreveport, the uninsured patients undergoing cardiac surgery are no less educated than the insured and that these patients seek and have access to the same quality of care. These are, indeed, important observations, for it means that perhaps we need to reconsider many of our previously held views regarding the uninsured and tailor our analyses to more specific subsets of patients before reaching broad-based conclusions.

In this regard I have several questions that I would like to ask Dr. Mancini. Can you help us understand why the uninsured patients seemed to have a better long-term survival? Is this simply a function of age at time of treatment or are there other factors involved, such as a sampling bias introduced by a nonrandomized telephone survey? How many patients were actually lost to follow-up during the study period and did this actually vary between the two cohorts? Since your study represents an analysis of patients who underwent coronary artery bypass surgery over the course of 10 years, have there been any recent changes in your state’s healthcare policies that have impacted favorably or unfavorably on the access to care or the delivery of care? Finally, while certainly not the focus of your paper, at some point in time your hospital, as well as other university hospitals with a high percentage of uninsured patients, will have to determine whether they can afford to continue to provide high-cost specialty care. At your hospital, do you know what this threshold might be for cardiac surgery?

Again, I want to congratulate Dr. Mancini on a fine presentation and the Association for the opportunity to discuss this paper.

DR. BENJAMIN LI (Shreveport, Louisiana): I would like to add my congratulations to Dr. Mancini for her excellent presentation and thank her for the opportunity to review the manuscript beforehand. In these days of escalating influence and regulatory oversight by the federal government and third-party payors on physicians’ practice patterns, studies such as this that attempt to dissect and critically analyze variables that impact on clinical outcomes are most important and poignant. In this study involving close to 1,600 patients who underwent CABG at a state academic hospital, only 34% of the patients had some form of insurance, of which 70% were insured by Medicare. Thus, it may not be surprising to find that the mean age in the insured group, which comprise mostly Medicare patients, to be older than that of the uninsured group.

As this is a retrospective review, I wonder if Dr. Mancini might comment on the possibility of a form of lead-time bias that was introduced, in that the improved survival detected in the uninsured younger patients, who presented at an earlier time for surgery and, therefore, may potentially represent patients whose disease was perhaps identified at a different stage from those who are older Medicare-insured patients. My second question is about the fact that only 7% of the insured patients were by nongovernmental third-party private insurers whereas 70% of the Medicare patients, who may have shared quite similar characteristics with the uninsured group, except that they are not old enough to qualify for Medicare. Thus, would the results be similar if they were performed comparing the uninsured group with the 7% of privately insured group? Finally, since the comorbidities between the insured and the uninsured groups were similar, I wonder what factors lead to the requirement by the uninsured younger group for surgery early in their lives.

Again, I’d like to congratulate and thank Dr. Mancini and the Association for the opportunity to discuss this paper.

PRESIDENT AUST: I have a similar question to Dr. Li’s first question. I wonder how many of the uninsured patients would be insured by Medicare if they just reached 65 and, conversely, how many of the Medicare patients who are already 65 would have been uninsured had they been younger. Please, Dr. Mancini?

DR. MARY MANCINI (Shreveport, Louisiana): I appreciate all your comments. This is a confusing issue, and let me pose one definition with respect to Medicare and coronary artery disease. Patients with coronary artery disease, if they have Medicare, may not necessarily be 65 or over because of a regulation that deals with disability insurance. Therefore, some of these, about a third of the Medicare population, actually fall into a younger age group under this law. So the definition changes from our characteristic definition of Medicare.

Just to go through the questions. The uninsured with better outcomes in their younger presentation clearly presented earlier. Clearly, this study has some adverse selection built into it because it is a retrospective study. What we need to do with this group is, one: follow them out longer, and number two: initiate a prospective trial.

With respect to our return from phone calls, surprisingly enough, we generated over a 75% response rate. So, again, that was surprising based on this patient population. They seemed to be either very well indebted or had a loyalty to our institution, and so they were not hard to track. Not to mention, the group did an amazing job at persistence.

Recent changes in healthcare policy in our state: all I can say is it parallels the national elections. Right now, Medicaid has declined in this state, although there was just an issue in the newspaper that said that they found a $1.2 billion loophole. That word “loophole” in Louisiana makes me very nervous. We’ll see. That is the only answer I have.

In dealing with the economics of the institution: Dr. McDonald, if I’m wrong, correct me now or correct me later. We do have a tremendous amount of outsourcing. We also work outside the institution to help fund the division, and I really don’t think there is a threshold for discontinuing care. The institution has a mission to provide care to these patients. It has been a long-standing mission of the institution, and it won’t go away. The way we try to help is just to become very efficient at it and to decrease our cost as much as possible.

As far as our Medicaid and indemnity situation is concerned, you might as well look at those as the same group. So actually from 7%, you could go up to 30% as far as the total paying customer is concerned. And in cardiac surgery, in some states Medicaid pays better.

Clearly, there is a lead-time bias; that is not deniable. And again, following the longer time period will separate this out one way or the other.

Why did these people present earlier, particularly the uninsured? I have a bias in this data, and that is smoking. I really believe that if we look at this longer and if I could track it a little bit more closely–and we plan on sending out some more questionnaires and hopefully getting some honest answers–that smoking is probably going to be the culprit in this group.

I thank the Association and the discussants for their input.

Footnotes

Presented at the 112th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 4–6, 2000, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Mary C. Mancini, MD, PhD, Professor of Surgery, Dept. of Surgery, LSUHSC-Shreveport, 1501 Kings Highway, Shreveport, LA 71130.

E-mail: mmanci@lsuhsc

Accepted for publication December 2000.

References

- 1.Kleinman JC, Gold M, Makuc D. Use of ambulatory care for poor persons. Health Serv Res 1988; 19: 1011–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newacheck PW. Access to ambulatory care for poor persons. Health Serv Res 1988; 23: 401–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman HE, Aiken LH, Blendon RJ, et al. Uninsured working-age adults: characteristics and consequences. Health Serv Res 1990; 24: 811–823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafner-Eaton C. Physician utilization disparities between the uninsured and insured: comparison of the chronically ill, acutely ill, and well non-elderly populations. JAMA 1993; 269: 787–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aday LA, Andersen RM. The national profile of access to medical care; where do we stand? Am J Public Health. 1984; 74: 1331–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayward RA, Shapiro MF, Freeman HE, et al. Iniquities in health services among insured Americans; do working-age adults have less access to medical care than the elderly? N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, et al. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons and consequences. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolhandler S, Himmerstein DU. Reverse targeting of preventive care due to lack of health insurance. JAMA 1988; 259: 2872–2874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short PF, Lefkowitz DC. Encouraging preventive services for low-income children: the effect of expanding Medicaid. Med Care 1992; 30: 766–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billings J, Teicholz N. Uninsured patients in District of Columbia hospitals. Health Aff 1990; 9: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman JS, Gatsonis C, Epstein AM. Rates of avoidable hospitalization by insurance status in Massachusetts and Maryland. JAMA 1992; 268: 2388–2394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissman JS, Epstein AM. Case mix and resource utilization by uninsured hospital patients in the Boston metropolitan area. JAMA 1989; 261: 3572–3576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hand R, Sener S, Imperato J, et al. Hospital variables associated with quality of care for breast cancer patients. JAMA 1991; 266: 3429–3432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg ER, Chute CG, Stukel T, et al. Social and economic factors in the choice of lung cancer treatment: a population-based study in two rural states. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 612–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenneker MB, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The association of payer with utilization of cardiac procedures in Massachusetts. JAMA 1990; 264: 1255–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braveman P, Oliva G, Miller MG, et al. Adverse outcomes and lack of health insurance among newborns in an eight-county area of California, 1982–1986. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurie N, Ward NB, Shapiro MF, et al. Termination from Medi-Cal. Does it affect health? N Engl J Med 1984; 311: 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lurie N, Ward NB, Shapiro MF, et al. Termination of Medi-Cal benefits; a follow-up study one year later. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 1266–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fihn SD, Wicher JB. Withdrawing routine outpatient medical services; effects on access and health. J Gen Intern Med 1988; 3: 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brook RH, Ware JE Jr, Rogers WH, et al. Does free care improve adult health? Results from a randomized controlled trial. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 1426–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman JJ, Makuc DM, Kleinman JC, et al. National trends in educational differences in mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1989; 129: 919–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold MR, Franks P. The social origin of cardiovascular risk: an investigation in a rural community. Int J Health Serv 1990; 20: 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR. Age, socioeconomic status and health. Milbank Q 1990; 68: 383–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet 1991; 337: 1387–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ, Backlund E, et al. Mortality in the uninsured compared with that in persons with public and private health insurance. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154: 2409–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franks P, Clancy CM, Gold MR. Health insurance and mortality: evidence from a national cohort. JAMA 1993; 270: 737–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford E, Cooper R, Castaner A, et al. Coronary arteriography and coronary bypass surgery in whites and other racial groups relative to hospital-based incidence rates for coronary artery disease: findings from NHDS. Am J Public Health 1989; 79: 437–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg KC, Hartz AJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Racial and community factors influencing coronary artery bypass graft surgery rates for all 1986 Medicare patients. JAMA 1992; 267: 1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadley J, Steinberg SP, Feder J. Uninsured and privately insured patients, condition on admission, resource use and outcome. JAMA 1991; 265: 374–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hannan E, Kilburn H, O’Donnell J, et al. Interracial access to selected cardiac procedures for patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease in New York State. Med Care 1991; 29: 430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberman A, Cutter G. Issues in the national history and treatment of coronary heart disease in black populations: surgical treatment. Am Heart J 1984; 108: 688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valdez RB, Dallek G. Does the health care system serve black and Latino communities in Los Angeles county? An analysis of hospital use in 1987. Claremont (CA): The Tomas Rivera Center; 1991.

- 33.Wenneker MB, Epstein AM. Racial inequalities in the use of procedures for patients with ischemic heart disease in Massachusetts. JAMA 1989; 262: 253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leape LL, Hillborne LH, Bell R, et al. Underuse of cardiac procedures: do women, ethnic minorities, and the uninsured fail to receive needed revascularization? Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]