Abstract

Objective

To determine the success of a clinical pathway for outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in an academic health center, and to assess the impact of pathway implementation on same-day discharge rates, safety, patient satisfaction, and resource utilization.

Summary Background Data

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is reported to be safe for patients and acceptable as an outpatient procedure. Whether this experience can be translated to an academic health center or larger hospital is uncertain. Clinical pathways guide the care of specific patient populations with the goal of enhancing patient care while optimizing resource utilization. The effectiveness of these pathways in achieving their goals is not well studied.

Methods

During a 12-month period beginning April 1, 1999, all patients eligible for an elective LC (n = 177) participated in a clinical pathway developed to transition LC to an outpatient procedure. These were compared with all patients undergoing elective LC (n = 208) in the 15 months immediately before pathway implementation. Successful same-day discharges, reasons for postoperative admission, readmission rates, complications, deaths, and patient satisfaction were compared. Average length of stay and total hospital costs were calculated and compared.

Results

After pathway implementation, the proportion of same-day discharges increased significantly, from 21% to 72%. Unplanned postoperative admissions decreased as experience with the pathway increased. Patient characteristics, need for readmission, complications, and deaths were not different between the groups. Patients surveyed were highly satisfied with their care. Resource utilization declined, resulting in more available inpatient beds and substantial cost savings.

Conclusions

Implementation of a clinical pathway for outpatient LC was successful, safe, and satisfying for patients. Converting LC to an outpatient procedure resulted in a significant reduction in medical resource use, including a decreased length of stay and total cost of care.

Since its introduction, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallbladder disease. 1 Rapid recovery after LC and increasing experience with its postoperative course have led to progressively shorter postoperative stays. Most recently, true outpatient LC, without an overnight admission, has been advocated. Although initially reported in 1990 2 and subsequently supported by others, 3–10 this practice has not been universally adopted. Others have urged caution and raised questions regarding the safety of the outpatient approach. 11–13 The factors contributing to successful outpatient LC are poorly defined. Potential barriers to this process are medical, attitudinal, and institutional. Medical barriers such as patient comorbidities and postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting are common issues preventing same-day discharge. 6–8 Consensus protocols and comprehensive patient and health professional education can overcome multiple barriers by managing expectations and providing a uniform plan and timeline for care. These “clinical pathways” incorporate a multidisciplinary approach to streamline patient care at the institutional level and provide enhanced team communication and coordination, leading to improved efficiency of care and patient satisfaction.

Stimulated by patient interest, questions regarding the feasibility and safety of outpatient LC were raised at our institution in early 1998. Prior, isolated attempts at outpatient LC by individual surgeons proved difficult because this was contrary to standard practice at that time, and implementation was stifled by several barriers, including physician and patient concerns regarding safety and the difficulties inherent in changing complex institutions. Reports up to that time, mainly from ambulatory surgery facilities or small groups of surgeons in practice, suggested that routine outpatient LC was feasible. 2–10 The ability to replicate these successes in a complex organization such as an academic health system was uncertain. Consequently, in February 1998 we developed a clinical pathway tool for patients undergoing elective LC. This initiative provided an institutionalized plan of care to overcome these barriers to facilitate the outpatient performance of LC. We hypothesized that successful pathway implementation would result in a predictable, high rate of same-day discharge for patients having elective LC. Our goals were to assess the feasibility, safety, and acceptability of providing this procedure on a true outpatient basis. Finally, we predicted that successful implementation would result in decreased institutional resource utilization and real cost savings.

METHODS

Pathway, Patients, and Care

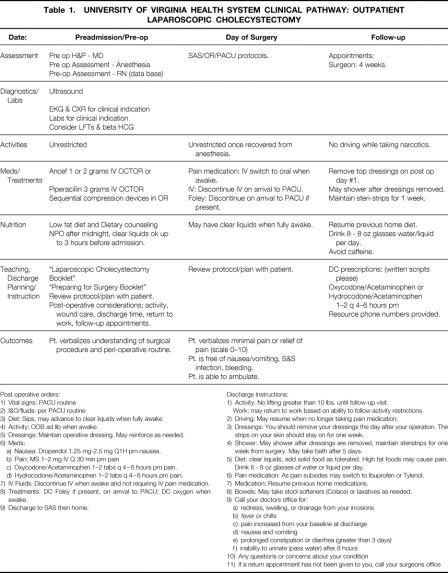

Table 1 shows the clinical pathway developed by consensus (surgery, anesthesiology, and nursing) for outpatient LC. The nursing units (clinic, preadmissions, ambulatory surgery [SAS], operating room [OR], and postanesthesia care unit [PACU]) provided care guidelines for their areas; pharmacists provided drug use guidelines. Guidelines were based on data from the current literature, where available. Few specific physician practice guidelines were stipulated. Before pathway implementation, participating staffs were educated about the pathway and its structure and goals.

Table 1. UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA HEALTH SYSTEM CLINICAL PATHWAY: OUTPATIENT LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY

Post operative orders: 1) Vital signs: PACU routine 2) I&O/fluids: per PACU routine 3) Diet: Sips, may advance to clear liquids when fully awake 4) Activity: OOB ad lib when awake. 5) Dressings: Maintain operative dressing. May reinforce as needed. 6) Meds: a) Nausea: Droperidol 1.25 mg-2.5 mg Q1H prn nausea. b) Pain: MS 1–2 mg IV Q 30 min prn pain c) Oxycodone/Acetaminophen 1–2 tabs q 4–6 hours prn pain. d) Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen 1–2 tabs q 4–6 hours prn pain. 7) IV Fluids: Discontinue IV when awake and not requiring IV pain medication. 8) Treatments: DC Foley if present, on arrival to PACU; DC oxygen when awake. 9) Discharge to SAS then home. Discharge Instructions: 1) Activity: No lifting greater than 10 lbs. until follow-up visit. Work: may return to work based on ability to follow activity restrictions. 2) Driving: May resume when no longer taking pain medication. 3) Dressings: You should remove your dressings the day after your operation. The strips on your skin should stay on for one week. 4) Shower: May shower after dressings are removed, maintain steristrips for one week from surgery. May take bath after 5 days. 5) Diet: clear liquids, add solid food as tolerated. High fat foods may cause pain. Drink 8 - 8 oz glasses of water or liquid per day. 6) Pain medication: As pain subsides may switch to Ibuprofen or Tylenol. 7) Medication: Resume previous home medications. 8) Bowels: May take stool softeners (Colace) or laxatives as needed. 9) Call your doctors office for: a) redness, swelling, or drainage from your incisions b) fever or chills c) pain increased from your baseline at discharge d) nausea and vomiting e) prolonged constipation or diarrhea (greater than 3 days) f) inability to urinate (pass water) after 8 hours 10) Any questions or concerns about your condition 11) If a return appointment has not been given to you, call your surgeons office

The pathway was implemented April 1, 1999, and all consecutive patients undergoing elective LC were evaluated during a 12-month period ending April 31, 2000. The transition and postpathway groups were created to gain measures of system performance during the initial period of pathway implementation and acceptance. Pathway eligibility was based on the surgeon’s judgment. Preoperative evaluations were noted in the pathway. Other requirements included a responsible adult to escort the patient home and to be present the night of surgery, access to medical care within 30 minutes of their lodging, and use of a telephone. Hotel accommodations adjacent to our hospital were offered for the night of surgery if needed.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed using a standard four-trocar technique with carbon dioxide insufflation. Residents from surgery and anesthesiology participated in all cases, which were performed by the faculty physicians. Patients had perioperative antibiotics, sequential compression devices on their lower extremities, and trocar site infiltration with bupivacaine before incision, because this was our standard before the pathway. All other perioperative medications and interventions were performed according to each individual surgeon’s and anesthesiologist’s practice. Patients recovered in the PACU according to standard protocols, with regular assessments for pain and nausea. When patients were stable and discharge criteria were met, they were transferred to SAS. When able to take liquids, ambulate freely, and void spontaneously, patients were discharged. Initial postoperative follow-up by phone was done through the physician’s office. If discharge criteria were not met or at the physician’s discretion, patients were admitted.

Database and Statistical Analysis

Patient clinical and financial data were obtained from charts and the Clinical Data Repository, an electronic database that stores all digital records generated within the institution. All records were searched for LC and cross-referenced with accounting records. Data were reviewed by a trained independent observer and verified by a physician reviewer. A random sample of patients in the pre- and postpathway groups were surveyed by telephone to verify the reliability of our electronic records. A structured interview (five-point Likert scale) was done to address overall satisfaction, time to return to daily activities, adequacy of the length of stay, and any specific problems they encountered during their care. Details from the OR, PACU, and charts were collected to account for the details of all unplanned admissions and readmissions.

Differences between groups were assessed using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests of independence for categorical variables. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for proportions were calculated using exact binomial distributions. Analyses were done that adjusted for potential confounding factors (sex, age, race, indication for surgery), and there were no meaningful changes in results seen from unadjusted analyses. Patient survey group mean scores on each item were compared using t tests for independent samples. Total and per-patient costs were calculated by summing service-specific costs. During the study period, internal central service (supply) costs increased without any increase in products or services provided, as a result of changes in accounting methods. In-depth analysis confirmed no change in vendors, vendor charges, or actual supply utilization. To allow comparison, we adjusted the price for central services, using the hospital consumer price index for the postpathway period (6.1%), so that pre- and postpathway central service costs were based on prepathway dollars.

RESULTS

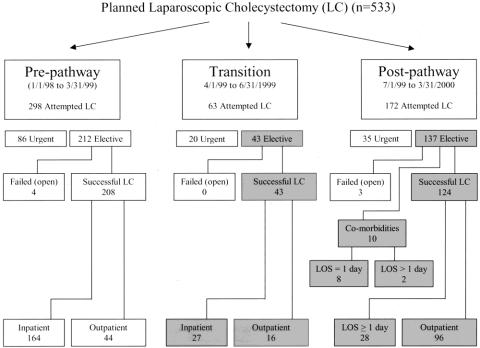

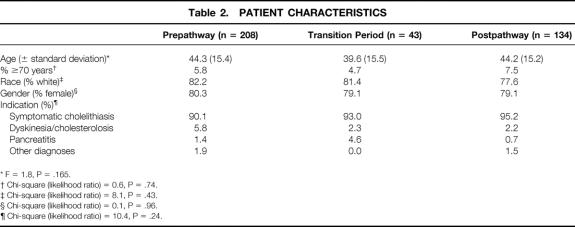

Patients undergoing successful, elective LC (January 1998 to March 2000; n = 385) were reviewed (Fig. 1). The study population included patients during the first 3-month trial of the pathway (transition period, April to June 1999; n = 43) and those during the 9 months after the transition period (postpathway, July 1999 to March 2000; n = 134). An historical population of patients undergoing LC during the 15 months immediately preceding pathway implementation (prepathway, January 1998 to March 1999; n = 208) served as the comparison. Patients who underwent conversion to an open procedure (n = 7) and those who underwent an urgent or emergent LC (n = 138) or a primary open procedure (n = 31) were not included in this analysis. Patient characteristics did not differ between groups for any category (Table 2). Patient ages ranged from 18 to 83 years.

Figure 1. Distribution of patients by study period. Shaded areas refer to patients who were eligible for the clinical pathway and are included in the analysis. LOS, length of stay.

Table 2. PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

* F = 1.8, P = .165.

† Chi-square (likelihood ratio) = 0.6, P = .74.

‡ Chi-square (likelihood ratio) = 8.1, P = .43.

§ Chi-square (likelihood ratio) = 0.1, P = .96.

¶ Chi-square (likelihood ratio) = 10.4, P = .24.

Feasibility of Same-Day Discharge, Pathway Noncompliance, and Safety

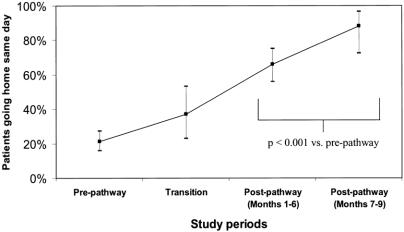

The average length of stay for prepathway patients was overnight (0.92 hospital days). This decreased during the transition (0.63 days) and postpathway periods (0.34 days). A significantly greater same-day discharge rate occurred after elective LC for the entire postpathway period (72%). This increased to 88% in the final 3 months (Fig. 2). The proportion of patients staying 2 or more days declined between the pre- and postpathway periods from 9% to 5%.

Figure 2. Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Data points represent the proportion of patients going home on the day of surgery, with error bars signifying 95% confidence intervals. “Pre-pathway” refers to patients who received care before clinical pathway implementation (n = 208). “Transition” refers to patients who received care during the 3-month adjustment period immediately after pathway implementation (n = 43). “Post-pathway (Months 1–6)” refers to the first 6 months of the pathway after the transition period (n = 99). “Post-pathway (Months 7–9)” refers to the group of patients receiving care during months 7 through 9 after the transition period (n = 35). A significantly higher proportion of patients receiving care during postpathway months 1 to 9 had a “true” outpatient procedure compared with prepathway patients (P < .001).

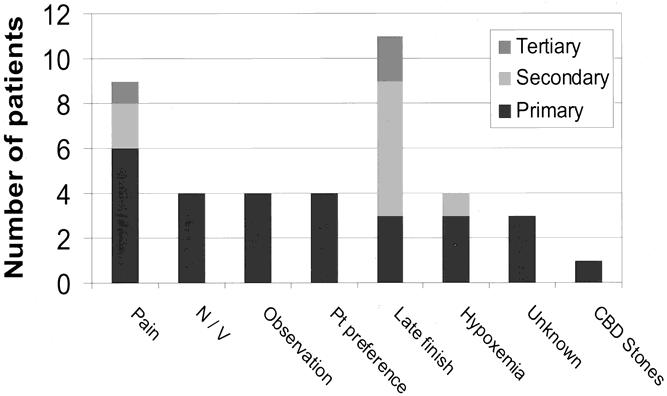

Based on preoperative decisions, 10 (7.5%) of the 134 patients who underwent elective LC in the postpathway period were admitted for comorbidities; thus, 124 “pathway-eligible” patients received care using the clinical pathway. Twenty-eight (23%) of these pathway-eligible patients had unplanned admissions for the reasons noted in Figure 3. Of these, 25 were admitted during the first 6 months of the postpathway period. Postoperative pain (n = 6) occurred in 5% of all pathway-eligible patients and accounted for 21% of unplanned admissions. Four patients (3%) were admitted because the operating surgeon believed they required overnight observation, accounting for 14% of all primary reasons for admission. These included one patient with bleeding from the liver bed, another with bleeding from a liver biopsy site, one with a gangrenous gallbladder associated with a difficult dissection, and one with a difficult dissection around the cystic duct. All patients admitted for nausea and vomiting had rescue antiemetic therapy in the PACU before admission. Four patients desired postoperative admission.

Figure 3. Reasons for pathway noncompliance. Patients eligible for the pathway who had an unplanned admission are shown (n = 28). Reasons were scored as the primary, secondary, or tertiary cause for unplanned admission. Pain was the most common primary cause for unplanned admission, but suboptimal procedure scheduling contributed to the largest number of unplanned admissions when all reasons were summed. N/V, nausea and vomiting; Pt Preference, patient preference; CBD Stones, choledocholithiasis.

Of the unplanned admissions, 23 (82%) patients were discharged home the next day without complications, and none required subsequent readmission. Five required longer hospital stays for the following indications (one patient each): hypoxemia, acute cholecystitis with a gangrenous gallbladder, choledocholithiasis requiring endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, nausea and vomiting, and severe pain. Of those patients admitted for comorbidities, 80% were discharged after an overnight stay without complications or subsequent readmission. Only one patient with comorbidities (congestive heart failure and asthma) had a perioperative complication (dyspnea not requiring intubation).

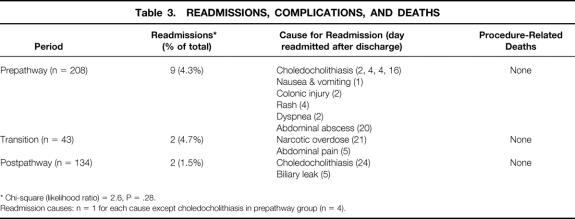

Readmission after LC was not statistically different among the study periods (Table 3), decreasing from 4.3% to 1.5% between the pre- and postpathway periods. For the two patients readmitted after going home the same day, neither would have avoided readmission by remaining in the hospital the night of surgery. No postoperative procedure-related deaths occurred, based on a review of our institutional records and death certificates from the Virginia Department of Health.

Table 3. READMISSIONS, COMPLICATIONS, AND DEATHS

* Chi-square (likelihood ratio) = 2.6, P = .28.

Readmission causes: n = 1 for each cause except choledocholithiasis in prepathway group (n = 4).

Patient Satisfaction

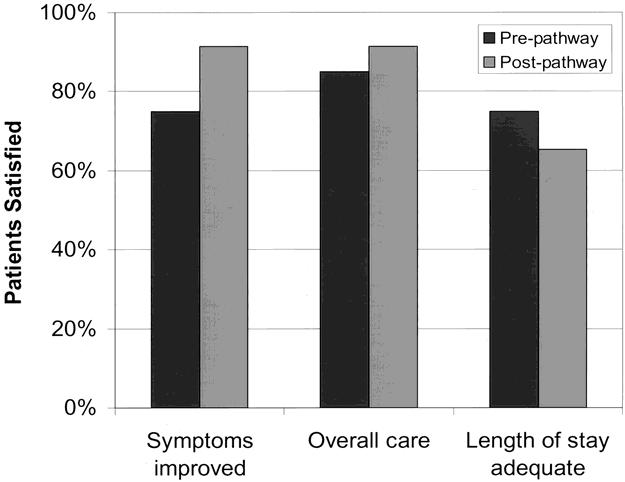

In the patient survey, there were no significant differences in the responses of pre-and postpathway groups in any of the question categories (Fig. 4), although small sample sizes may have limited the ability to detect differences. Twenty-five percent of patients in the prepathway group would have preferred a longer hospital stay, versus 35% in the postpathway group (P = .48). There were no differences between the groups in time out of work, or average time required for return to “normal” activities of daily living (16 days).

Figure 4. Patient satisfaction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pre-pathway (n = 20) and post-pathway patients (n = 23) completed a structured telephone interview ranking the listed items on a five-point Likert scale. The number of patients indicating the highest two scores were summed and reported as the percentage satisfied. There was no difference in scores between the periods by chi-square analysis.

Resource Utilization

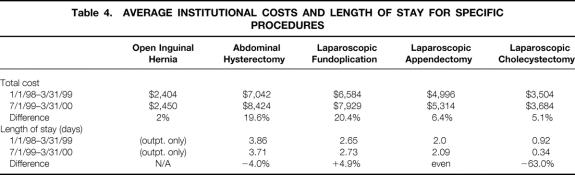

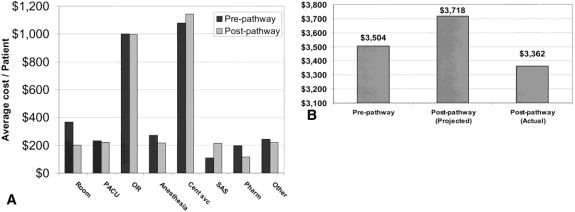

The transition of LC to an outpatient procedure resulted in the availability of an additional 89 bed-days during the course of a year. Unadjusted LC costs increased during the study period (5.1%), which was less than the national hospital consumer price index (6.1%). To review cost changes at our institution, the average unadjusted costs and percentage change between the pre- and postpathway periods for other procedures were calculated (Table 4). To understand these costs, a detailed analysis was performed on comprehensive categorical cost data. Compared with prepathway costs, crude costs in most categories were unchanged or decreased (Fig. 5 A). PACU costs (which are time-based) did not change with outpatient LC. Conversely, SAS costs increased 99% (from $108 per patient to $215). Internal central service (supply) costs appeared to increase without a change in products or services, as described above. Figure 5 B shows the average total costs for all patients undergoing LC during the pre- and postpathway study periods based on prepathway dollars. The average total inflation-adjusted cost savings per case was $356, for overall annualized savings of $62,300. Average cost for pathway-eligible, “true” outpatients ($3,567) was approximately $651 less than the average cost for pathway-eligible patients staying overnight ($4,128).

Table 4. AVERAGE INSTITUTIONAL COSTS AND LENGTH OF STAY FOR SPECIFIC PROCEDURES

Figure 5. (A) Costs for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Average costs per patient were broken down into the major cost categories for all patients cared for in the pre- and post-pathway implementation periods. PACU, postanesthesia care unit; OR, operating room; Cent svc, central services (supplies); SAS, ambulatory surgery unit; Pharm, pharmacy. (B) Average overall costs per patient. Pre-pathway cost denotes the average cost for all patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy before implementation of the clinical pathway. Projected post-pathway costs were calculated by multiplying the pre-pathway cost by the hospital consumer price index (6.1%) during the study period. Actual post-pathway costs were observed costs adjusted for changes in accounting methods that coincided with pathway implementation.

DISCUSSION

Pathway Development and Introduction: Feasibility, Safety, and Noncompliance

Motivated by patient interest, we investigated the feasibility and safety of outpatient LC beginning in February 1998. Until that time, a 23-hour stay was our standard for LC. Although the feasibility and safety of outpatient LC had been reported, 2–10 this practice did not appear to be widespread, and its applicability to a large academic setting was unclear. Essentially all of these reports were from small groups of surgeons in community hospital ambulatory surgery units or freestanding outpatient facilities. Most were done without the apparent involvement of residents (surgery or anesthesia). In addition, the factors necessary for successful outpatient care were uncertain. Several authors used strict selection criteria for patient inclusion, 3,5,6,8,9 whereas others reported no exclusion criteria in considering patients for outpatient LC. 2,4,7,10 Likewise, some authors described detailed intraoperative and postoperative strategies to minimize postoperative problems, 3,4,6–8 whereas others specifically avoided any such strategies. 2,5,9,10

With the limitations and lessons of these studies in mind, the clinical pathway for elective outpatient LC described in this report was developed and implemented. Our results show that pathway implementation led to similar rates of same-day discharge for our patients as those reported in the literature. By the end of the study period, 88% of all patients were successfully discharged home on the day of surgery, with an average length of stay of 0.34 days. These data also confirm the feasibility of outpatient LC without sacrifices in patient safety. The readmission rate was low, and a postoperative admission would not have prevented readmission in either case. Likewise, rates of surgical death and complications were not different after institution of outpatient LC.

Successful implementation of this pathway is notable for several points. First, it was accomplished in the context of a moderate-sized academic medical center with residents of varying levels (postgraduate year 1 to fellow) participating in all of the cases. Second, 12 faculty surgeons and more than 15 faculty anesthesiologists or nurse anesthetists participated. Thus, this implementation strategy and the transition of LC to an outpatient procedure are feasible in a large institution that trains residents. Similarly, success is possible with a large, diverse group of physicians, many with individual differences in their practice styles. At the outset of our study, it was uncertain whether the successes reported by practicing surgeons for outpatient LC could be translated to an institutional setting such as ours. Our results, combined with those of several recent reports, 14,15 confirm the efficacy and safety of outpatient LC in large academic training programs.

Third, these results were achieved in unselected patients. All patients who had an elective LC during the postpathway period were a part of this analysis, including those older than 70 and those with comorbidities. Initially during development, we considered several exclusion criteria, but no consensus on uniform guidelines for pathway participation could be defined. In addition, there was little support for one exclusion criterion over another, particularly those based on age or physiologic status. 16–18 Thus, a patient’s eligibility for pathway participation was left to each surgeon’s clinical judgment. Our results support offering outpatient LC to all patients eligible for elective LC, without the use of specific screening protocols to exclude patients before surgery. It appears that increased institutional experience with this pathway was associated with a greater rate of same-day discharge, evidenced by the increase in the last 3 months of the study. Age was not a specific contraindication to successful outpatient LC: 5.2% of participating patients were older than 70, and 63% were treated as outpatients. To maximize the success and safety of outpatient LC, some groups advocate selecting only “healthy” patients. 3,5,6,8,9 We agree that some selection criteria are prudent for freestanding outpatient surgery centers to ensure that appropriate patients are treated at these facilities. However, patients potentially eligible for outpatient LC who do not meet these criteria should be considered for surgery in another venue. Our approach was feasible because our ambulatory surgery unit is within the context of the main hospital and operating suites. Our data reflect those from other studies, confirming the feasibility and safety of outpatient LC in unselected patients, 4,7,10 including those older than 70 or with comorbidities. 16 Several patients were excluded from pathway participation before surgery by their surgeon on the basis of comorbidities; no patient was excluded during the last 3 months of the study. Despite reports in the literature indicating the safety of outpatient surgery in these patients, this suggests that surgeon or institutional experience leading to a comfort level with these patients is an important factor in the successful completion of LC as an outpatient procedure.

The final point of note is the clinical pathway design. Our results call into question the need for an explicit pathway that dictates all aspects of the patient’s care, including individual physician practices. Because postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting have been reported as significant problems in ambulatory surgical patients, several authors have developed and advocated the use of detailed strategies to combat these problems during LC. 3,4,6–8,14,15,19,20 Although they have been mostly successful, equivalent results have been observed without using specific perioperative techniques. 5,9,10 Thus, the utility of these specific interventions in facilitating successful outpatient LC remains unclear and is the subject for further studies.

In designing our pathway, we chose an intermediate position. We sensed that the major change required to make the transition to an outpatient procedure involved addressing the culture (attitudes) surrounding the care of this patient population. Because the expected care typically included a 23-hour overnight admission at our institution, we focused on addressing the feasibility and safety of LC as an outpatient procedure, primarily by educating physicians and other healthcare professionals involved in the process. Once the pathway was implemented, these educational initiatives were expanded to include the patients. We anticipated that these educational efforts would reset the expectations for what was perceived as a normal postoperative course after LC. We also believed that education about this initiative would be critical to its success. This cultural change was supported by the development of the clinical pathway itself. As outlined in the pathway, this document primarily details an administrative structure that provides a common, institution-wide template for the care of these patients. This pathway details the aspects of care that we sought to standardize across the institution and was directed at minimizing variance in the care provided by rotating healthcare providers who may interact with these patients only intermittently (e.g., residents, nurses, students). Few other physician-specific guidelines, such as anesthetic, antiemetic, analgesic, or procedural details, were included in the pathway. In meetings with participating surgeons and anesthesiologists, there were clear sentiments that several techniques were amenable to and successful in the ambulatory surgery setting. Most individuals desired leeway to practice in the fashion to which they were accustomed and that they believed was optimal for each patient. One part of the pathway that specified details of physician care was the postoperative orders. Again, because residents rotating through our services wrote most of these instructions, we sought to minimize variance in the orders. In particular, promethazine was eliminated in favor of droperidol or ondansetron to avoid its sedating side effects and to eliminate this as a potential source of unplanned admissions. Standardized discharge criteria were developed and patients had to meet these before being discharged. Finally, this pathway provided suggested guidelines, not mandates, for care, and its use was strictly voluntary on both the attending surgeons’ and patients’ parts.

Although we had a high rate of same-day discharge after elective LC, a detailed analysis of patients admitted after surgery suggests room for improvement. The largest group was patients with comorbidities thought to preclude outpatient LC, based on their preoperative evaluation. Most (80%) were discharged home the first postoperative day without complications or readmissions, suggesting they might have been candidates for outpatient LC. Thus, by determining the need for admission after surgery rather than before surgery, more of these patients may have been treated on an outpatient basis. Postoperative pain was the largest primary cause for unplanned admission, and documentation of local anesthetic administration before incision could not be found in some of these patients. Local anesthetic administration and other analgesic strategies could reduce admission for this reason. 21,22 However, this is not universally accepted: some authors report high same-day discharge rates (90–97%) without the use of local anesthetic at the port sites. 5,6 Nonetheless, use of a local anesthetic is associated with minimal risks and may reduce the incidence of unplanned admission for postoperative pain. The number of admissions for patient preference is likely to decrease with patient education and as this procedure is performed more routinely on an outpatient basis. The admission rate for postoperative nausea and vomiting was low and comparable to published data for patients receiving routine prophylactic antiemetics. 3,6,8,14,20 We do not believe that our low rates or those reported by others not using prophylactic antiemetics justify the routine use of these medications during outpatient LC. Although not a significant primary cause for unplanned admission, OR scheduling contributed to unplanned admissions in several instances. In general, if the procedure was completed too late in the day to allow adequate recovery, the patient was admitted. Scheduling these cases earlier in the day will prevent this reason as a primary cause for unplanned admission. It also may allow patients with self-limited problems such as nausea, vomiting, or hypoxemia to become eligible for same-day discharge by allowing a longer postoperative recovery time. Together, these data suggest that increasing institutional experience, better patient education, and strategies to eliminate common postoperative problems can lead to greater same-day discharge rates after LC.

Several lessons are inherent based on our data and those of others. First, LC can be successfully and safely performed as an outpatient procedure in an unselected population of patients. It can be performed in a variety of practice settings, whether they are single-surgeon practices, large academic training programs, freestanding ambulatory surgery centers, or outpatient units within the main hospital. Second, universal participation at the institutional level can be achieved but requires a substantial front-end commitment to staff and patient education. Our experience mirrors that of other authors: that is, education is a common, critical component contributing to the success of this process. We used a formal pathway document, but this clearly is not required for successful implementation in all circumstances. Several successful reports of outpatient LC used no formal pathway, although the care outlined in those reports constitutes de facto pathways. Some of these informal pathways, in fact, had elaborate plans for perioperative care. We chose to formalize our pathway for the reasons noted above and the likelihood that it would decrease errors associated with the care of these patients. Third, successful implementation of outpatient LC is possible with only a few specific practice guidelines, without significantly restricting individual physician practices. This should promote the general acceptance and success of these pathways by allowing clinicians flexibility in the care of their patients. Finally, time and experience, whether for an individual or a large organization, appear to be essential for attaining optimal outcomes after pathway introduction. This is apparent in our experience and that of others, with increasing rates of same-day discharge as experience with outpatient LC increases.

Patient Satisfaction

As noted previously, the primary impetus for exploring outpatient LC at our institution was patient requests. We were interested, therefore, in patients’ perceptions about LC as an outpatient procedure. Overall, patients were highly satisfied with their medical care, which was not altered by use of the clinical pathway. Although these results can be criticized for the small sample size, they confirm anecdotal impressions relayed by patients during their postoperative visit and are similar to other reports. 2,7,14–16 Interestingly, a large minority of our patients in both the pre- and postpathway groups stated they would have preferred a longer hospital stay. This has not been reported in most series. In one study of patients undergoing outpatient LC in a model setting, 71% stated they required an overnight admission. 19 Subsequently, this group reported that 20% of patients undergoing true outpatient LC would have preferred an overnight stay. 14 In another study, 95% of patients reported overall satisfaction with the outpatient experience, although 89% stated they could not return to work the same day as their surgery and 77% stated they could not return to work on the first postoperative day. 15 Thus, we would concur with other authors that outpatient LC is highly acceptable to patients, even though many desire some convalescence in a hospital setting.

Resource Utilization

Although our primary interest was not resource utilization or cost savings, we sought to understand the impact of pathway implementation on these issues. As anticipated, institution of the pathway was associated with decreased resource utilization and overall cost savings. An important resource saving for us was bed utilization, because we are frequently over capacity in terms of available beds. However, cost savings were not immediately apparent in our initial analysis. In the most conservative estimate, based on unadjusted bulk average costs, pathway implementation blunted the expected rise in costs predicted by the consumer price index and by comparison with other procedures. Another moderate estimate, in light of the accounting change, showed cost savings of $356 per patient. These savings were modest compared with those estimated by other authors. 3,5,14,19 This may reflect costs that already have been pared to a minimum for a 23-hour stay, with the possible exception of room costs. Cost analysis confirmed that most of the savings resulted from decreased room costs, but this was partially offset by increases in other areas. A second potential reason for the modest savings was the inclusion of all patients undergoing elective LC during the postpathway period in the analysis, including those admitted for one or more nights. Unadjusted costs for postpathway patients discharged the same day ($3,567 per patient) compared with patients admitted for a single night ($4,128 per patient) showed a cost savings of $651 per patient. A third reason for limited savings was the use of our main operating rooms for outpatient LC. Hospital costs typically are more than those in freestanding outpatient surgery centers. The average cost of LC at our outpatient surgery facility was $1,700 per patient compared with $3,567 per patient for procedures performed on an outpatient basis in the hospital’s ambulatory unit. Thus, we could improve cost savings by moving eligible patients to our outpatient facility.

In conclusion, clinical pathway implementation for LC effecting conversion from an inpatient to an outpatient procedure is feasible, safe, cost-effective, and not associated with sacrifices in patient satisfaction. Its implementation can be successful in an academic training center. Success depends on extensive education of the healthcare professionals providing the care and the patients undergoing this care. Outpatient LC is feasible for all patients being considered for elective LC. These successes are facilitated by the construction of guidelines for the overall care of these patients. Finally, pathway implementation and outpatient LC result in the decreased use of hospital resources and consequent cost savings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ken Scully, Robert Pates, James McGowan, Catherine Burns, William Wilson, and Evangeline Calland, without whom this manuscript would not have been possible.

Discussion

DR. KEITH D. LILLEMOE (Baltimore, Maryland): I’d like to congratulate Dr. Adams and his co-authors for presenting an excellent paper and thank them for the opportunity to review the manuscript and discuss this paper.

The authors have demonstrated that true outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed safely and efficiently in an academic health center, with both a low rate of postoperative admission and subsequent need for readmission for problems after return to home.

The authors also demonstrated a high rate of patient satisfaction as well as a modest cost savings. Another advantage not emphasized in their presentation is the preservation of two of our most valuable resources – hospital beds and house staff hours.

The authors also emphasize the importance of a critical pathway, albeit, not too rigid, in the importance of implementing their fine results.

Two years ago at the SSAT we presented and subsequently published in the Journal of GI Surgery, our initial results with true outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy at our own academic health center. The current paper essentially mirrors our results with a low rate of admission, 6%, a low rate of readmission, 5%, high patient satisfaction, and substantial cost savings.

In our study we found also that a critical clinical pathway and patient education were keys in obtaining the results. One major difference in the two studies, however, was the strong emphasis in our study on a very set, rigid anesthetic management protocol, specifically using new agents designed to minimize postoperative pain, sedation, nausea, and vomiting. Specifically, newer and perhaps somewhat more expensive agents such as Propofol or Toradol, as well as local and topical application of Marcaine were felt to be important in contributing to our results.

My questions for Dr. Adams is, do you feel, although not described as a rigid protocol, that anesthetic management for outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy needs to be different than those procedures performed as inpatients?

Secondly, we also follow an essentially all-comer philosophy with respect to attempting outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. But, like you, have the safety net of being immediately adjacent to our main hospital. Do you feel that a different philosophy is necessary for the true free-standing outpatient surgery center?

Thirdly, I note that a significant number of your admissions were contributed to by late-in-day starts, which did not allow the normal PACU recovery. What was the average length of your PACU stay? In our series, the average length of PACU stay was 3 hours. This is also important because most PACU’s charge on a per minute basis.

Finally, the authors emphasize the importance of clinical pathways in their results, maintaining that the diverse group of surgeons, house staff, nurses and anesthesiologists involved in the care of these patients makes this important. We at Hopkins are also advocates of clinical pathways and, at our institution, these measures have not been instituted only for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but for major abdominal, thoracic and vascular procedures. We feel this aids in not only guiding the healthcare professionals but also provides a step-by-step outline for the patients to help set their own goals and objectives in their recovery.

I would therefore ask Dr. Adams, have they at UVA implemented clinical pathways for other procedures other than laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Again, I’d like to thank the Southern and the authors for the opportunity to discuss the paper.

C. RANDLE VOYLES (Jackson, Mississippi): I also echo the sentiment of Dr. Lillemoe in that this is an extremely well done study that outlines the safety of performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy on a complete ambulatory basis. We initiated same-day discharge in our practice several years ago and then we took the additional step in 1997 of moving a selected number of our patients to a completely free-standing ambulatory surgery center. Common sense suggests that a low-risk operations not only could be but should be performed in low-cost environment if safety could be assured. As of last Friday, 230 cholecystectomies have been performed in our ambulatory center; this figure amounts to 35% of all cholecystectomies performed by me in just over two and a half years. In this selected group of patients, there has been no need for immediate conversion to open operation. In one patient, we abandoned laparoscopy after finding a scarred and calcified gallbladder and transferred the patient to the hospital for open cholecystectomy. Another patient required relaparoscopy several hours post-op for a port site bleeder and was discharged the next morning; no transfusions were required and she was discharged the next morning. Of the balance, 77% were discharged the same day and the following the next morning – numbers that are comparable to the authors’. Our facility provides overnight stay which is essential to allow us to operate later into the day, particularly on patients who live significant distances from our center.

I echo the authors’ opinion that safety can be maintained but would suggest that cost savings may be even more substantial. For example, the authors reported a total cost – not charge – of $3300 with over $1000 of the cost going to supplies (i.e., disposable instruments). These numbers are fairly typical for cholecystectomy in large institutions. By contrast, our cost in the free-standing ambulatory center is less than $1000. We use no disposable instruments and, indeed, our cost for all disposables as reported last year is only $99 and those disposable items include gowns, gloves, drapes, q-tips, bandaids and one packet of clips to be used with a reusable applier.

The same practice pattern is applicable to selected patients having anti-reflux operations. Since August of last year, I have performed 41 laparoscopic Nissens in the ambulatory surgery center. This amounts to just over half of the patients in this time frame. Instrument choice is similar to cholecystectomy, except we use the bipolar electrosurgery to take down the short gastric vessels. We have not used the harmonic scalpel in over two years and feel that it is oversold, over-rated and over-priced.

After a period of attitudinal adjustment, we accepted that some of these patients can also go home on the afternoon of their operation. Indeed, 45% of my ambulatory center patients went home on the same day. The remaining went home the next morning.

I would like to ask the authors to comment on the following: the biggest bang for the buck comes not from the critical pathway, unless that pathway leads to an ambulatory surgery center with careful selection of cost-effective instruments. Would you outline your plans to increase utilization of the ambulatory facility?

Finally, shouldn’t the ambulatory surgery center be a financially distinct entity from the mother center to avoid inevitable cost shifting and a progressive loss of cost-competitiveness from our academic centers for our most common operations?

Thank you very much.

DR. HIRAM C. POLK, JR. (Louisville, Kentucky): Ladies and Gentlemen, I’d like to make a couple of comments about this paper and describe a somewhat similar effort with a broader base.

Number one, I think it is always smart when you can get in front of a nationally developing trend, and that is clearly what the authors have done with this, and I congratulate them on that.

There is another very soft touch in the manuscript that I think came through in the presentation: they talk about guidelines but not mandates. The group psychology involved in taking on something like this is very, very important, and surgeons do especially poorly when they are told ‘you must.‘ So this has been a significant undertaking.

The gain of 89 bed days presumably has some real value to this if it carries over and lets the surgical staff do some other cases. If it does not, it may or may not be of value.

The patient satisfaction studies were impressive. One of the later slides showed very briefly that most of those savings are actually in bed utilization. And I agree with Dr. Voyles that there is a broader area for savings beyond simple bed utilization.

Finally, the pace of innovation in university hospitals is going to have to match that which is going on in ambulatory surgery centers. If you don’t do that, you are going to be holding the bag in every sense of the word.

Let me describe an experience we have had that parallels this and reinforces most of the points that the Charlottesville group have made. First of all, we addressed four major issues: one, broaden the concept to a larger number of doctors and a larger number of hospitals. The second issue that I think is perhaps overridingly important is returning some of these savings to benefit the beleaguered surgical practice and the beleaguered surgical department in which most of us work today. We need to put some of those savings back in a way that it means something to the surgeon in question.

Finally, these things all need to be surgeon-led, and we certainly developed some simple protocols under the leadership of Neal Garrison, a fellow of this Association, which have now been refined and helped a lot with this. Let me tell you, we have a group of 70 surgical specialists. That’s ENT, orthopedics, urology, and general surgeons, working in teaching and nonteaching hospitals. We have done 35 CPT codes along this line. The average savings of these patients in all that setting is of the same magnitude, a little better than that presented today, but of the same magnitude. You can accomplish that. That has been done on the basis of 7,000 patients with 2 deaths and 1.2 percent complications. So you can do this. The trick is how to get people onboard and taking part in it.

We have found, when we identify a better practice, that it can be rapidly assimilated, particularly since the surgeons are benefitting somewhat financially from the better medical management of these patients. A good example of that is an expensive antiemetic which we were able to pass around to a lot of people and essentially end its use in everybody’s practice on a voluntary basis, just because of its very expense.

So when you begin to look at this scenario, your partners here need to be the hospital. They need to share benefits with the surgeon group or the surgical department, and the opportunity to move with major national health plans that are similarly interested in this is really important.

This is a key issue and a key place for surgeons to be working today. I enjoyed the paper. Thank you very much.

DR. THOMAS R. GADACZ (Augusta, Georgia): I’d like to ask just two really simple questions.

One, did you review any of the patients that were not included in the pathway? Because it really is critical to define exclusion, and so I think this is a group that you really should take a look at to identify those patients where this would not apply.

The second question is: what survey tool did you use for your satisfaction? Was this a standard tool, or was this a survey tool that your group composed?

Thank you very much.

DR. REID ADAMS (Charlottesville, Virginia): I’d like to thank everybody for their kind comments.

Dr. Lillemoe, in reference to your questions, we did not use a strict anesthetic protocol as we outlined in the paper and as you noted. We did discuss a strict anesthetic protocol as part of the pathway development with our anesthesia colleagues. And their feeling was that there were many ways to give an ambulatory anesthetic and they wanted the leeway to do what they felt comfortable with in their own practice, so we left it at that. It turns out that that was successful. We didn’t know before we started the study whether that would indeed be the case.

I suspect that most of them have their favorite ambulatory protocols, because they all rotate through our free-standing ambulatory center and give ambulatory anesthesia on a routine basis. Thus, they have developed things that work in their own practice and that have been translated into success in this pathway.

In terms of what we would do different for patients if we were going to move them to our free-standing ambulatory center, we have actually already begun to do that. It is not just simply a matter of moving those patients; there are some logistic problems at our own institution. That facility is quite full, and moving those patients wholesale would be difficult. I do think that you probably need some more stringent guidelines, at least in our own instance, where there are not inpatient-stay facilities associated with that unit. If they needed an overnight stay, they would have to be transferred back to the main hospital, which would incur additional cost and possibly safety issues.

I think that those patients that have co-morbidities or that you suspect may not do well based upon your clinical judgment, should be done in the center that you have and that we have adjacent to our main operating facilities.

We did not look at PACU time, but our PACU costs were no different between the pre- and postpathway groups, which I think is a reasonable surrogate to suggest that our PACU time was not increased by moving these patients to the outpatient setting.

On the other hand, in a slide that I did not show and was illustrated in the manuscript, we did incur an increased cost in our ambulatory unit, and that is simply because the intensity of care in that unit was increased by moving these patients to that facility. That offset our savings in room charges, and that is why the difference in the pre- and postpathway cost does not equal a room charge because of this additional charge that we incurred in our ambulatory unit.

In terms of other clinical pathways, we also are advocates of pathways throughout our practice. We have pathways for thyroid, pathways for colon, among others, so we use these freely in our own institution.

Dr. Voyles, how do you move patients to the outpatient center? I mentioned that briefly, and again, in our own instance, it is limited by the size of our facility at this point. And unlike your center, we don’t have an overnight stay capacity. I think if we incorporated that into our center, that would allow us to extend the ability to provide care for these patients in a more cost-effective manner.

Should our ambulatory unit be a separate facility? Yes, it should be, both administratively and financially if you want to maximize your cost savings. Our free-standing unit is a separate entity. The ambulatory unit that we used in this study is not a separate entity; it is incorporated into the operating administrative and financial entity included in our main hospital. And so it incurs some of the higher costs that are required for the overhead of the institution.

Dr. Polk, I want to thank you for your kind comments.

Dr. Gadacz, in reviewing patients, we did look at all patients that were eligible for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and they are all accounted for in the manuscript. We did not include patients that had urgent or emergent cholecystectomies. Those that had open cholecystectomies were those that were converted to an open procedure when the intent was to have an elective laparoscopic procedure. So they are all accounted for, and they are in that slide of those patients that fell out. Ten patients fell out because of comorbidities. And, as I said, 80% of those were discharged the next day without any problems and probably could have been done on an outpatient basis. Likewise, the patients that I outlined on the previous slide show that most of the patients had presumably treatable problems such as pain, nausea, and an educational issue of simply desiring to stay overnight.

In terms of what survey tool we used, we used one that we developed in-house that was a simple 5-question survey on a 5-point Likert scale to try to assess whether the patients were satisfied, whether their symptoms were resolved, and whether or not they wished to have additional hospitalization to what they had received.

I thank the Association for the opportunity to present this paper and to provide comments.

Footnotes

Presented at the 112th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 4–6, 2000, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Reid B. Adams, MD, FACS, HSC, Dept. of Surgery, Box 800709, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908-0709.

E-mail: rba3b@virginia.edu

Accepted for publication December 2000.

References

- 1.Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new gold standard? Arch Surg 1992; 127: 917–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddick EJ, Olsen DO. Outpatient laparoscopic laser cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 1990; 160: 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narain PK, DeMaria EJ. Initial results of a prospective trial of outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiorillo MA, Davidson PG, Fiorillo M, et al. 149 ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc 1996; 10: 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farha GJ, Green BP, Beamer RL. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a freestanding outpatient surgery center. J Laparoendosc Surg 1994; 4: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam D, Miranda R, Hom SJ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as an outpatient procedure. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 185: 152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mjaland O, Raeder J, Aasboe V, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephenson BM, Callander C, Sage M, et al. Feasibility of “day case” laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1993; 75: 249–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor E, Gaw F, Kennedy C. Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy feasibility. J Laparoendosc Surg 1996; 6: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voitk AJ. Establishing outpatient cholecystectomy as a hospital routine. Can J Surg 1997; 40: 284–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berci G. Editorial comment. Am J Surg 1990; 160: 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders CJ, Leary BF, Wolfe BM. Is outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy wise? Surg Endosc 1995; 9: 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer TW, Morris JB, Lowenstein A, et al. The consequences of a major bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lillemoe KD, Lin JW, Talamini MA, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a “true” outpatient procedure: initial experience in 130 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willsher PC, Urbach G, Cole D, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic surgery. Aust NZ J Surg 1998; 68: 769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voitk AJ. Is outpatient cholecystectomy safe for the higher-risk elective patient? Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 1147–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meridy HW. Criteria for selection of ambulatory surgical patients and guidelines for anesthetic management: a retrospective study of 1553 cases. Anesth Analg 1982; 61: 921–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, et al. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA 1989; 262: 3008–3010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleisher LA, Yee K, Lillemoe KD, et al. Is outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy safe and cost-effective? A model to study transition of care. Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 1746–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberman MA, Howe S, Lane M. Ondansetron versus placebo for prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 2000; 179: 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehlet H. Acute pain control and accelerated postoperative surgical recovery. Surg Clin North Am 1999; 79: 431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaloliakou C, Chung F, Sharma S. Preoperative multimodal analgesia facilitates recovery after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 1996; 82: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]