Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the clinical utility of frozen section in patients with follicular neoplasms of the thyroid in a randomized prospective trial.

Summary Background Data

The finding of a follicular neoplasm on fine-needle aspiration prompts many surgeons to perform intraoperative frozen section during thyroid lobectomy. However, the focal distribution of key diagnostic features of malignancy contributes to a high rate of noninformative frozen sections.

Methods

The series comprised 68 consecutive patients with a solitary thyroid nodule in whom fine-needle aspiration showed a follicular neoplasm. Patients were excluded for bilateral or nodal disease, extrathyroidal extension, or a definitive fine-needle aspiration diagnosis. Final pathologic findings were compared with frozen sections, and cost analyses were performed.

Results

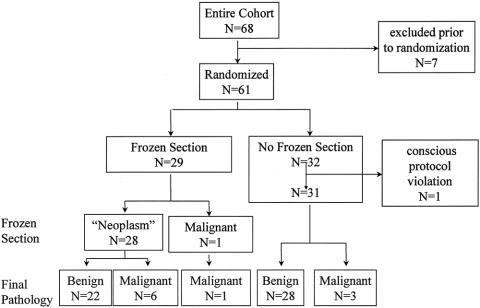

Sixty-one patients met the inclusion criteria. Twenty-nine were randomized to the frozen-section group and 32 to the non-frozen-section group. In the non-frozen-section group, one patient was excluded when gross examination of the specimen was suggestive of malignancy and a directed frozen section was diagnostic of follicular carcinoma. Frozen-section analysis rendered a definitive diagnosis of malignancy in 1 of 29 (3.4%) patients, who then underwent a one-stage total thyroidectomy. In the remaining 28 patients, frozen section showed a “follicular or Hürthle cell neoplasm.” Permanent histology demonstrated well-differentiated thyroid cancer in 6 of these 28 patients (21%). Of the 31 patients in the non-frozen-section group, 3 (10%) showed well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma on permanent histology. Complications were limited to one transient unilateral vocal cord dysfunction. All but one patient had a 1-day hospital stay. There were no significant differences between the groups in surgical time or total hospital charges; however, the charge per informative frozen section was approximately $12,470.

Conclusions

For the vast majority of patients (96.4%) with follicular neoplasms of the thyroid, frozen section is neither informative nor cost-effective.

The term “follicular neoplasm” is broadly applied to a heterogeneous group of thyroid tumors characterized by a proliferation of thyroid epithelial cells growing in a follicular pattern. Because this group encompasses both benign and malignant tumors, treatment decisions and prognosis ultimately rely on more specific classification. Regrettably, further classification is often not possible by fine-needle aspiration (FNA). In the case of follicular and Hürthle cell carcinomas, FNA is ineffectual in recognizing tumor invasion, an obligatory diagnostic feature. 1,2 In the case of the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma, FNA tends to underappreciate specific nuclear alterations because of their focal and random distribution. 3,4 The probability of malignancy in a thyroid lesion demonstrated by FNA to be a follicular neoplasm is approximately 20%. 2,5 Accordingly, excision is recommended for patients harboring this heterogeneous group of nodules.

Confusion surrounding optimal patient management is compounded in the operating room. Many surgeons perform an ipsilateral thyroid lobectomy and isthmusectomy and then rely on intraoperative frozen-section analysis to establish a more precise diagnosis. If the lesion is found to be malignant, a one-stage total thyroidectomy is advocated. If the lesion is benign, most surgeons and endocrinologists believe that an ipsilateral thyroid lobectomy is adequate treatment. 6,7 Unfortunately, intraoperative frozen-section evaluation can rarely distinguish benign from malignant neoplasms. 1,2,5,8–11 The focal nature of tumor invasion may elude detection because of the limited sampling inherent to frozen-section evaluation. Moreover, the artifact and cellular distortion induced by tissue freezing may mask the subtle morphologic atypia that characterizes the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. As a result, some have called into question the standard practice of frozen-section evaluation as a reliable means to guide the surgical management of thyroid nodules. 1,2,8,11,12

In a large retrospective study, we previously showed that intraoperative frozen section failed to render useful information in 87% of patients with follicular neoplasms of the thyroid. 2 Further, frozen section appropriately modified the surgical procedure in only 4 of 120 (3.3%) patients. Likewise, Hamburger and Hamburger 11 showed that only 3 of 359 (0.8%) frozen-section analyses contributed decisively to surgical treatment; Shaha et al 13 reported similar limitations of frozen-section analysis for follicular neoplasms. Based on these results, we questioned the routine use of intraoperative frozen section as a useful and cost-effective diagnostic tool for classifying follicular neoplasms of the thyroid. 2 Although most investigators agree with this recommendation, some believe that this technique is a useful routine intraoperative diagnostic adjunct. 9,14 In addition, clinical factors such as age, sex, and tumor size may not be helpful in differentiating benign from malignant follicular neoplasms. 10

Despite growing concern regarding its efficacy, frozen-section analysis remains entrenched as a standard practice in the surgical management of thyroid nodules. Many surgeons are reluctant to abandon this ritualistic, albeit dubious, exercise in the absence of randomized prospective studies that either confirm or contest retrospective observations. With this in mind, we designed a randomized prospective trial evaluating the clinical utility of intraoperative frozen-section analyses for follicular neoplasms of the thyroid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

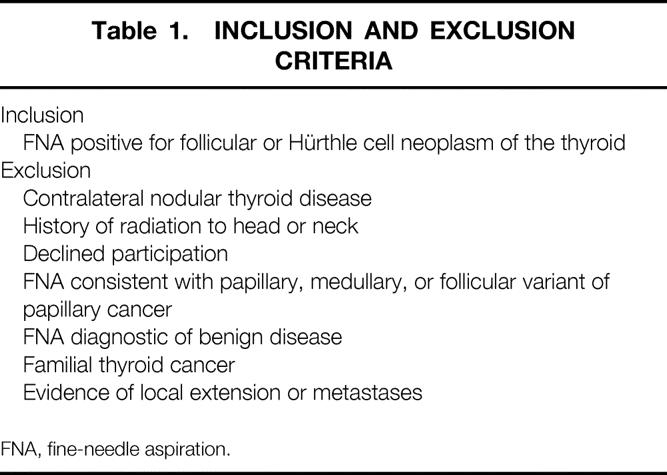

All patients referred to the Johns Hopkins Thyroid Tumor Center were eligible for this trial if they had a dominant thyroid nodule demonstrated by FNA to be a follicular or Hürthle cell neoplasm of the thyroid. All FNA specimens from outside institutions were internally reviewed to ensure specimen adequacy and the accuracy of diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they had contralateral nodular thyroid disease; had received radiation to the head or neck in childhood; declined to participate; had FNA specimens that were clearly diagnostic of either a benign or malignant tumor or suggestive of papillary, medullary, or the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid; had familial thyroid cancer; or had evidence of local extension or metastases (Table 1). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with institutional review board approval. A detailed history and physical examination, including direct or indirect laryngoscopy, was obtained in all patients. Imaging studies including ultrasound, scintigraphy, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging scans were not routinely used.

Table 1. INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

FNA, fine-needle aspiration.

Randomization was not performed until the time of surgical exploration. At that time, the surgeon (R.U.) exposed the ipsilateral thyroid lobe, examined the contralateral thyroid lobe, and palpated the regional lymph nodes. Patients were eliminated from this study if they showed contralateral nodular thyroid disease, direct invasion of tumor into contiguous structures, or evidence of nodal metastases. Patients were then randomized during surgery to the frozen-section group or the non-frozen-section group by a random number code maintained in individual sealed envelopes in the operating room. In all patients, a lobectomy and isthmusectomy was performed and the specimen was evaluated by a pathologist and the surgeon. For each patient randomized to frozen section, at least one area of the tumor was sampled showing the tumor interface with the surrounding nonneoplastic thyroid tissue.

If the frozen section was diagnostic of malignancy, a total thyroidectomy was performed during the initial exploration. If the frozen section was not diagnostic of malignancy, the contralateral thyroid lobe was left in situ. Reapproximation of the strap muscles and closure of the wound were identical in both groups. Specifically, the wound was closed while frozen sections were being performed. If the frozen section was diagnostic of malignancy, the wound was reopened and the contralateral thyroid lobe was excised.

Permanent histologic analysis was performed in all patients. The specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In every instance, the entire nodule was evaluated by histologic examination. The permanent-section diagnosis was confirmed for all cases by a senior pathologist with experience in endocrine pathology (W.H.W.).

The prospective data recorded included preoperative and intraoperative findings, surgical time, anesthesia time, time required to generate an intraoperative pathologic consultation, length of hospital stay, perioperative complications, and hospital charges. If the final pathologic analysis showed a thyroid malignancy, additional consultation was obtained from the endocrinologists, and the patient was offered a second-stage completion thyroidectomy. Similar data were obtained for this remedial procedure.

Statistical comparisons were performed by the two-tailed Student t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

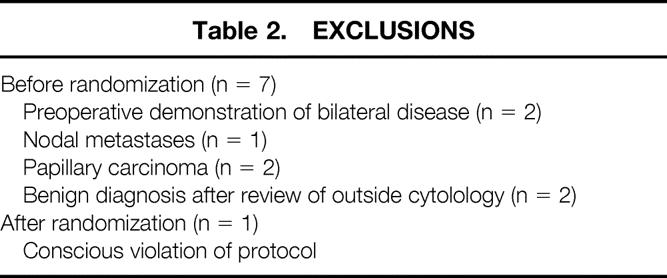

The overall stratification is shown in Figure 1. Sixty-eight consecutive patients participated. Seven patients were excluded before randomization because of preoperative demonstration of bilateral disease (n = 2), nodal metastasis (n = 1), or a modification of their initial FNA diagnosis after review of outside cytologic material that revealed papillary carcinoma (n = 2) or a benign diagnosis (n = 2) (Table 2). Accordingly, 61 patients underwent intraoperative randomization after showing the absence of contralateral disease, direct extension into contiguous structures, or the presence of nodal metastases. Twenty-nine patients were randomized to the frozen-section group and 32 patients to the non-frozen-section group.

Figure 1. Randomization scheme.

Table 2. EXCLUSIONS

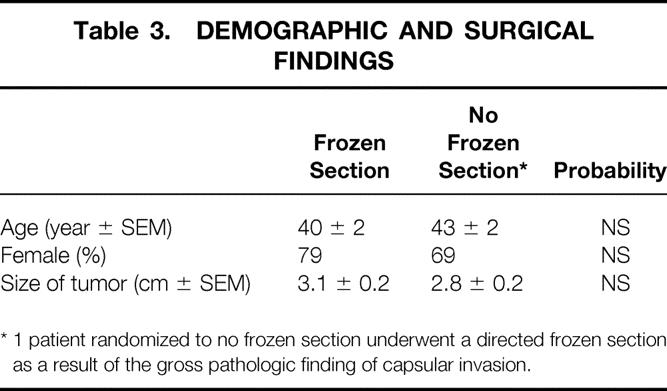

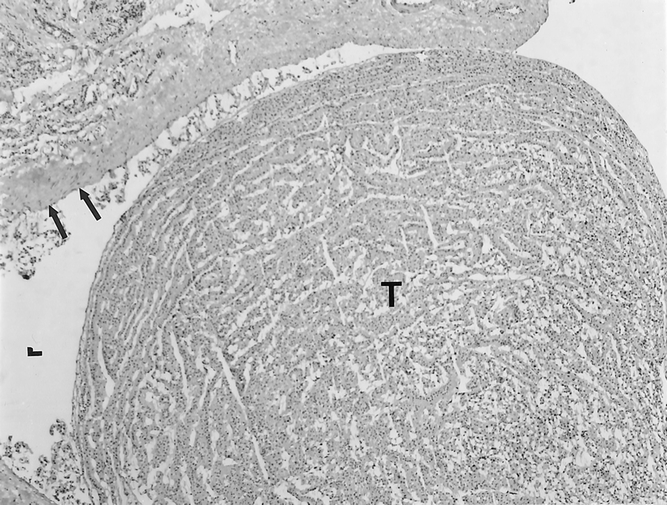

Demographic data and surgical findings are shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in terms of patient age, sex distribution, or tumor size. In the non-frozen-section group, one patient was excluded because of a conscious protocol violation when sectioning of the tumor in the pathology suite suggested areas of transcapsular tumor invasion. This prompted the pathologist to perform a guided frozen section that showed tumor invasion of a large-caliber vessel, confirming the impression of a malignant tumor (Fig. 2), and a one-stage total thyroidectomy was performed. The frozen-section diagnosis of a follicular carcinoma was subsequently confirmed by permanent histology.

Table 3. DEMOGRAPHIC AND SURGICAL FINDINGS

* 1 patient randomized to no frozen section underwent a directed frozen section as a result of the gross pathologic finding of capsular invasion.

Figure 2. Frozen section showing an invasive tumor (T) filling a large-caliber vascular lumen (L). The vascular endothelial lining is indicated by the arrows.

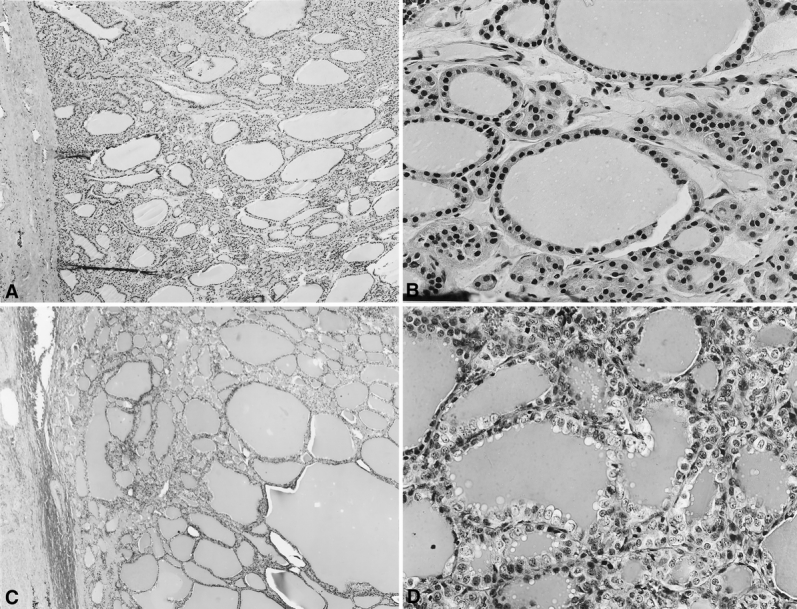

In the frozen-section group, frozen-section analysis showed malignancy (follicular carcinoma) in only 1 of 29 (3.4%) patients. Based on the frozen-section interpretation of carcinoma, this patient underwent a one-stage total thyroidectomy. Final pathology in this patient confirmed a follicular carcinoma. In the remaining 28 patients, frozen-section analysis confirmed the FNA diagnosis of a “follicular neoplasm” but yielded no additional useful information (Fig. 3). However, permanent histologic analysis showed well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma in 6 of these 28 patients (21%), and a completion second-stage total thyroidectomy was performed in all. These cancers included the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma (n = 4), minimally invasive follicular carcinoma (n = 1), and minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma (n = 1). The remaining 22 “neoplasms” were all benign (follicular adenomas, n = 11; Hürthle cell adenomas, n = 2; nodular hyperplasias, n = 9). The permanent histology corresponding to the “follicular neoplasm” in Figures 3 A and 3B is shown in Figures 3 C and 3D. In this patient, the permanent histology showed the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma.

Figure 3. Comparison of frozen-section and permanent-section histopathology in a case of a follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. The frozen section is shown in A (low power) and B (high power). In the frozen section, the diagnostic features of malignancy cannot be appreciated. Specifically, there is no infiltration of the surrounding capsule, papillary formations are absent, and the nuclear atypia of papillary carcinoma are not well developed. The permanent section is shown in C (low power) and D (high power). In this well-fixed tissue, the characteristic nuclear features of papillary carcinoma (nuclear enlargement, optic clearing and crowding) are much easier to appreciate.

Three of the 31 patients (10%) who were randomized not to undergo frozen section were found to have cancer on permanent histology: the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma, minimally invasive follicular carcinoma, and minimally invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma (one patient each). Although more carcinomas were present in the frozen-section group, the difference was not significant. A second-stage completion total thyroidectomy was also performed in each of these patients. The remaining 28 nodules in this group were all benign: follicular adenoma (n = 12), Hürthle cell adenoma (n = 3), and nodular hyperplasia (n = 13).

Complications were limited to one transient unilateral vocal cord dysfunction that occurred in the non-frozen-section group. Complete resolution was observed 1 month after surgery by direct laryngoscopy.

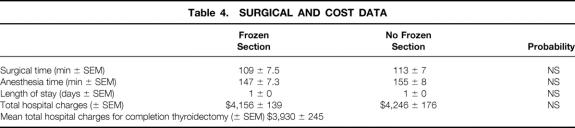

The time required to render an intraoperative pathologic consultation based on frozen-section analysis was 26 ± 1.7 minutes (range 15–48). Comparisons of the surgical time, anesthesia time, length of hospital stay, and total hospital charges are shown in Table 4. There were no significant differences between the groups in any of these outcomes. However, the mean charge per frozen section was $430. Because 29 frozen sections were performed in the frozen-section arm and only 1 was informative, the mean charge per informative frozen section was $12,470.

Table 4. SURGICAL AND COST DATA

DISCUSSION

The optimal management of follicular neoplasms of the thyroid continues to generate significant controversy. Inherent limitations in the ability of FNA to discriminate between benign and malignant lesions minimize the clinical utility of this technique for follicular neoplasms of the thyroid.

Most experienced endocrine pathologists and surgeons agree that frozen-section analysis in this group of patients rarely yields useful information and may result in misleading data. 1,2,7 The Mayo Clinic group recently suggested that in their hands intraoperative frozen-section analysis played an integral role in the management of these patients. 13 Unfortunately, this retrospective analysis did not rely on FNA findings as the entrance criteria for the study. Further, many of the patients would have undergone a bilateral resection regardless of the FNA findings. The published comments and invited commentary dampen the enthusiasm for this technique.

The charge analysis in this study showed no overall difference between the two groups. This is not surprising because the charge for a frozen section represents a relatively small component of the total hospital charge. In addition, because the surgeon did not prolong the surgical procedure waiting for a frozen-section result, the length of surgery was also similar between the two groups.

Two patients benefited from intraoperative frozen-section analysis. In each one, an invasive follicular carcinoma was correctly diagnosed and a one-stage total thyroidectomy was performed. The fact that only 1 of 29 patients (3.4%) in the frozen-section arm benefited from frozen-section analysis verifies the insensitivity of this technique in routine cases. However, in the group of patients who did not undergo frozen section, a highly suspicious gross finding prompted a conscious protocol violation and a directed frozen section was diagnostic of malignancy. This observation supports gross examination of the fresh specimen and selective use of directed frozen sections in suspicious cases.

Most patients with dominant thyroid nodules undergo preoperative FNA. This technique has revolutionized and streamlined the assessment of thyroid nodules, and in the vast majority of patients is the only diagnostic procedure required. FNA analysis is extremely sensitive for conventional papillary and medullary thyroid cancers. However, it cannot discriminate between malignant and benign follicular lesions (this heterogeneous group includes pure follicular neoplasms, Hürthle cell neoplasms, and many neoplasms that ultimately prove to be the follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma). In these instances, frozen section has long been advocated to help the surgeon distinguish between a benign and a malignant tumor. We previously showed in a retrospective study that under these conditions, frozen section is unreliable, is of minimal clinical utility, and may even be misleading. 2 We have now confirmed these observations in a randomized prospective study showing that in only 3.4% of patients did frozen section contribute to patient management.

The lack of sensitivity of FNA or frozen section in follicular neoplasms of the thyroid could theoretically be overcome by using adjunctive molecular techniques. Preliminary results indicate that such techniques, including analysis of telomerase, may prove to have clinical relevance. 15 However, until well-designed clinical trials prove the clinical utility of this or other techniques, we continue to recommend abandoning routine frozen-section analysis as an unnecessary and rarely informative procedure. We urge all surgeons to review the gross specimen with their pathology colleagues and to request a selected frozen section if there appears to be gross evidence of invasive tumor growth.

Discussion

DR. SAMUEL A. WELLS, JR. (Chicago, Illinois): Dr. Udelsman and his associates have established an enviable record of conducting excellent clinical studies of importance to practicing surgeons. Their present work is no exception: 1) It asks a simple important question, 2) It is well designed, and, 3) It has the potential to improve the management of patients with differentiated thyroid neoplasms. However, there remains a significant unresolved issue, because fifteen to twenty percent of their patients require an initial lobectomy and permanent section followed by completion thyroidectomy.

Last year was the 50th anniversary of the first prospective randomized clinical trial, a double-blinded study evaluating the use of streptomycin, compared to placebo, in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Unfortunately, there has never been, anywhere in the world, an adequate clinical trial evaluating the surgical treatment of thyroid carcinoma, where patients have been staged and prospectively randomized to either partial or total thyroidectomy. Dr. Udelsman is leading a group in the planning of a ‘large simple trial,’ which, if successful, will define the proper therapy for the majority of patients with this disease.

DR. JOHN B. HANKS (Charlottesville, Virginia): I rise also to say that this is really an excellent paper, and I think that Dr. Udelsman’s group has set the tone for exactly what Dr. Wells said, that further studies are needed. I would be very interested in Dr. Udelsman’s comments on looking a little bit more exactly into saving some OR time. He is very lucky because down south they spend a little bit more time doing the frozen sections, and we see increased operative time when we do frozen sections.

My second question has to do a little bit more with what Dr. Wells was hinting at. What would be their definition at going directly to a total thyroidectomy? Until we get the randomized studies, under what circumstances, knowing the information that they have, would they risk adjust their population? They talked about the majority of their patients were females, I believe 40 or less. And as you know, that represents a better prognosis circumstance for patients with thyroid cancer.

Would they do a thyroidectomy, say, for a 1 cm lesion that was follicular? And if it came back follicular cancer, maybe not do a second stage operation? Conversely, in an older male would they just go to a near total or a total thyroidectomy for a follicular lesion as advocated by a number of endocrine surgeons?

This is a really outstanding manuscript, and I appreciate reviewing it, and the membership will be educated by it when it comes out.

Thank you.

DR. ROBERT UDELSMAN (Baltimore, Maryland): Thank you, Dr. Aust. Dr. Wells gets right to the point. And the real question in thyroid cancer or thyroid nodules is what is the appropriate operation for the majority of patients with relatively small nodules or thyroid cancers? Is a total thyroidectomy appropriate for all patients with thyroid cancer? The answer is we just don’t know. There are groups that say yea and groups that say nay. And the only way we will ever answer that is with a randomized prospective trial.

The problem with this trial design – and we have been working on this for some time. Because thyroid cancer is so insidious and the recurrence rates can be so late, such a trial would require an enormous population. And only through an agency like the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group could we even approach it. We are trying to design that trial now. We have reservations because of statistical problems. But as Dr. Wells indicated, a simple trial, with a very large population base, almost certainly international, in which we would be willing to randomize our low-risk patients, to either a thyroid lobectomy or a total thyroidectomy is theoretically possible. We hope that members of this group would be willing to randomize patients in such a trial.

Dr. Hanks asked questions about operating time. It is interesting. Frozen section time is directly dependent upon the pathologist and the irritation of the surgeon. We find that if the surgeon goes into the frozen section suite it often takes a lot less time to get your answers back.

In this trial, the frozen section times were carefully measured, and the mean time was 26 plus or minus 1.7 minutes. I dare say that is not our routine frozen section time in the absence of a trial.

Dr. Hanks also addressed the issue about what are the indications for total thyroidectomy. The answer, and I refer back to Dr. Irvin, is that clinical judgment will never be replaced by a simple formula. If it is a 1 cm lesion in an otherwise very low-risk patient, it is hard for me to argue that a total thyroidectomy is in that patient’s long-term best interest.

On the other hand, when we see follicular or Hurthle cell lesions greater than 4 centimeters, especially in the elderly population, especially in men, we are more inclined to go directly to a total thyroidectomy in the absence of frozen section because in that setting we believe they are more likely to have malignancy. In our hands, it is at least 60%, and therefore, we justify the total thyroidectomy. So my answer to Dr. Hanks is clinical judgment in the absence of better data.

Thank you very much.

Footnotes

Presented at the 112th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 4–6, 2000, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Robert Udelsman, MD, MBA, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Blalock 688, 600 N. Wolfe St., Baltimore, MD 21287.

E-mail: rudelsma@jhmi.edu

Accepted for publication December 2000.

References

- 1.Chen H, Nicol TL, Rosenthal DL, et al. The role of fine-needle aspiration in the evaluation of thyroid nodules. Probl Gen Surg 1997; 14: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Nicol TL, Udelsman R. Follicular lesions of the thyroid: does frozen section evaluation alter operative management? Ann Surg 1995; 222: 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shemen LJ, Chess Q. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer: therapeutic implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998; 119: 600–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baloch ZW, Gupta PK, Yu GH, et al. Follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. Cytologic and histologic correlation. Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 111: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHenry CR, Thomas SR, Slusarczyk SJ, et al. Follicular or Hürthle cell neoplasm of the thyroid: can clinical factors be used to predict carcinoma and determine extent of thyroidectomy? Surgery 1999; 126: 798–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Nicol TL, Zeiger MA, et al. Hurthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid: are there factors predictive of malignancy? Ann Surg 1998; 227: 542–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller MP, Crabbe MM, Norwood SH. Accuracy and significance of fine-needle aspiration and frozen section in determining the extent of thyroid resection. Surgery 1987; 101: 632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udelsman R, Lakatos E, Ladenson P. Optimal surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 1996; 20: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingston GW, Bugis SP, Davis N. Role of frozen section and clinical parameters in distinguishing benign from malignant follicular neoplasms of the thyroid. Am J Surg 1992; 164: 603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neale ML, Delbridge L, Reeve TS, et al. The value of frozen section examination in planning surgery for follicular thyroid neoplasms. Aust NZ J Surg 1993; 63: 610–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamburger JI, Hamburger SW. Declining role of frozen section in surgical planning for thyroid nodules. Surgery 1985; 98: 307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Zeiger MA, Clark DP, et al. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: can operative management be based solely on fine-needle aspiration? J Am Coll Surg 1997; 184: 605–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaha A, Gleich L, DiMaio T, et al. Accuracy and pitfalls of frozen section during thyroid surgery. J Surg Oncol 1990; 44: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paphavasit A, Thompson GB, Hay ID, et al. Follicular and Hürthle cell thyroid neoplasms: is frozen section evaluation worthwhile? Arch Surg 1997; 12: 674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segev DL, Saji M, Phillips GS, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-based microsatellite polymorphism analysis of follicular and Hürthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 2036–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]