Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the accuracy of percutaneous, image-guided core-needle breast biopsy (CNBx) and to compare the surgical management of patients with breast cancer diagnosed by CNBx with patients diagnosed by surgical needle-localization biopsy (SNLBx).

Summary Background Data

Percutaneous, image-guided CNBx is a less invasive alternative to SNLBx for the diagnosis of nonpalpable mammographic abnormalities. CNBx potentially spares patients with benign lesions from unnecessary surgery, although false-negative results can occur. For patients with malignant lesions, preoperative diagnosis by CNBx allows definitive treatment decisions to be made before surgery and may affect surgical outcomes.

Methods

Between 1992 and 1999, 939 patients with 1,042 mammographically detected lesions underwent biopsy by stereotactic CNBx or ultrasound-guided CNBx. Results were categorized pathologically as benign or malignant and, further, as invasive or noninvasive malignancies. Only biopsy results confirmed by excision or 1-year-minimum mammographic follow-up were included in the analysis. Patients with breast cancer diagnosed by CNBx were compared with a matched control group of patients with breast cancer diagnosed by SNLBx.

Results

Benign results were obtained in 802 lesions (77%), 520 of which were in patients with adequate follow-up. Ninety-five of the 520 evaluable lesions (18%) were subsequently excised because of atypical hyperplasia, mammographic–histologic discordance, or other clinical indications. There were 17 false-negative CNBx results in this group; 15 of these lesions were correctly diagnosed by excisional biopsy within 4 months of CNBx. In two patients (0.9%), delayed diagnoses of ductal carcinoma in situ were made at 15 and 19 months after CNBx. Malignant results were obtained in 240 lesions (23%), 220 of which were surgically excised from 202 patients at our institution. Two lesions diagnosed as ductal carcinoma in situ were reclassified as atypical ductal hyperplasia and considered false-positive results (0.4%). For malignant lesions, the sensitivity and specificity of CNBx for the detection of invasion were 89% and 96%, respectively. During the first surgical procedure, 115 of 199 patients (58%) diagnosed by CNBx underwent local excision; 194 of 199 patients (97%) evaluated by SNLBx underwent local excision. For patients whose initial surgery was local excision, those diagnosed before surgery by CNBx had larger excision specimens and were more likely to have negative surgical margins than were patients initially evaluated by SNLBx. Overall, patients diagnosed by CNBx required fewer surgical procedures for definitive treatment than did patients diagnosed by SNLBx.

Conclusions

Diagnosis by CNBx spares most patients with benign mammographic abnormalities from unnecessary surgery. With the selective use of SNLBx to confirm discordant results, missed diagnoses are rare. When compared with SNLBx, preoperative diagnosis of breast cancer by CNBx facilitates wider initial margins of excision, fewer positive margins, and fewer surgical procedures to accomplish definitive treatment than diagnosis by SNLBx.

Improved mammographic detection of small, nonpalpable breast abnormalities has led to the increased detection of early-stage breast cancers and has contributed an estimated 30% improvement in breast cancer survival. 1 The benefit of screening mammography, however, is not without cost. Estimates indicate that up to 1 million mammographically detected lesions require biopsy each year, most (60–90%) of which are ultimately shown to be benign. Surgical biopsy to prove this represents the largest fraction of breast cancer screening costs. 2 In addition, patient discomfort, time away from work, and breast scarring are significant costs of surgical biopsy, especially when the results are benign.

Percutaneous, image-guided core-needle biopsy (CNBx) is being used increasingly to diagnose breast lesions. CNBx is faster, less invasive, and less expensive than surgical needle-localization biopsy (SNLBx). Numerous studies have shown the safety and accuracy of CNBx for the diagnosis of breast lesions. 3

Percutaneous CNBx can spare patients with benign lesions from unnecessary surgery and can facilitate the management of women with breast cancer. Diagnosis of breast cancer by CNBx can allow more specific discussion of treatment options (e.g., sentinel lymph node biopsy) between the surgeon and patient. Further, preoperative diagnosis of breast cancer by CNBx has been associated with higher rates of negative margins, fewer surgical procedures, and lower costs. 4–6

Although several series of CNBx have shown the advantages of percutaneous CNBx in the management of breast cancer, some debate still exists regarding the accuracy of CNBx as well as the role of CNBx in the management of breast disease. This study examines the impact of preoperative CNBx on the surgical management and outcome of mammographically detected breast cancer. We specifically document the diagnostic accuracy of CNBx and compare the surgical management of patients with breast cancers diagnosed by CNBx with concurrent patients with breast cancers diagnosed by traditional SNLBx.

METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed the outcome of 939 patients who had percutaneous image-guided CNBx of 1,042 mammographically detected lesions at our institution between August 1992 and February 1999. Radiologic data were collected prospectively and included type of abnormality, suspicion of malignancy (Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS], classification, American College of Radiology), biopsy technique, number of cores, complications, and biopsy results. Clinicopathologic data including surgical management, surgical pathology results, and mammographic follow-up were obtained from review of patient records. Biopsy results were categorized pathologically as benign or malignant. Malignant results were further categorized as invasive or noninvasive. Biopsy results were not included in our analysis unless confirmed by excision or by a minimum of 1-year mammographic follow-up.

Biopsy of 704 lesions was performed under stereotactic guidance; biopsy of 338 lesions was performed using ultrasound. Stereotactic CNBx was performed with patients in a prone position on a dedicated stereotactic table (Stereoguide; Lorad, Danbury, CT) with use of digital imaging. Before 1996, lesions were sampled with a 14-gauge automated large-core biopsy device (Multipass Gun; Bard, Covington, GA). Beginning in 1996, more than 90% of lesions were sampled with a 14-gauge or 11-gauge vacuum-assisted biopsy device (Mammotome; Biopsys Medical, Irvine, CA). Mammographically detected lesions that could be imaged by ultrasonography have undergone biopsy under ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound-guided CNBx was performed with patients in a supine position using the multipass technique under direct ultrasound guidance. More than 90% of abnormalities classified as calcifications or asymmetric densities underwent biopsy by stereotactic CNBx, whereas more than 50% of masses underwent biopsy by ultrasound-guided CNBx. The choice of guidance system, biopsy technique, and number of cores was left to the radiologist’s discretion.

For comparison of surgical management and outcomes, patients who had malignant lesions diagnosed by SNLBx at our institution during the study period were retrospectively identified. Reasons for SNLBx included surgeon preference, patient preference, medical condition that prohibited prone positioning, weight in excess of table limit, inability to image lesion by stereotaxis, and inability to take a biopsy sample from the lesion because of location (near axilla or pectoralis) or breast shape. A group of 199 patients was selected that was matched for age (± 10 years) and year of diagnosis (± 12 months) with the group of patients who had malignant lesions diagnosed by CNBx.

Data were evaluated for statistical difference by two-sample t test for comparison of continuous variables, Fisher exact test for comparison of ratios (two-tailed), and Mann-Whitney test for comparison of nonparametric data (Statistica for Windows; Statsoft, Tulsa, OK).

RESULTS

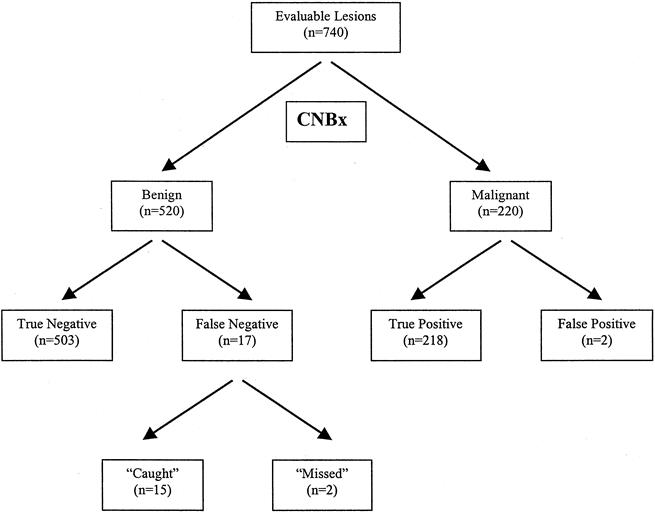

Benign diagnoses (including atypical hyperplasia) were rendered in 802 of 1,042 lesions (77%) in which CNBx was used (Fig. 1). Benign biopsy results (n = 282) that were unconfirmed by excisional biopsy or by mammographic stability greater than 1 year were not considered in subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 520 lesions surgically excised (n = 95) or stable mammographically greater than 1 year (n = 425; median 29 months), 503 were truly negative and 17 were falsely negative. Seventy-three of 802 lesions (9%) were excised within 4 months of CNBx, either for the diagnoses of atypical hyperplasia (n = 37) and papillomatosis (n = 2), for a nondiagnostic CNBx (n = 10), for discordance between the mammographic appearance and biopsy results (n = 8), or for other clinical indications (n = 17). Thirty-seven of 39 lesions diagnosed as atypical ductal hyperplasia or atypical lobular hyperplasia by CNBx were excised; of these, 10 (27%) were associated with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Fifteen of 17 false-negative results—including the 10 atypical hyperplasia diagnoses—were correctly diagnosed by excisional biopsy within 4 months of CNBx. An additional 22 of 802 benign lesions (3%) were excised greater than 4 months after CNBx as a result of a change in the lesion on mammographic follow-up or on clinical examination. Two patients had late diagnosis of same-site malignancies, for an actual miss rate of 0.9% for CNBx patients. One patient declined excisional biopsy after a nondiagnostic CNBx and was diagnosed with DCIS at 15 months after CNBx. A second patient with apocrine metaplasia by CNBx was diagnosed with DCIS at 19 months after CNBx.

Figure 1. Core-needle biopsy (CNBx) flowchart. The results of 740 biopsies were confirmed by surgical excision or by a minimum of 1-year mamographic follow-up.

Malignant results were obtained in 240 of 1,042 lesions (23%) in which CNBx was used (see Fig. 1). As expected, malignancy rates increased with level of mammographic suspicion, and our positive biopsy rates for BI-RADS 3 (“probably benign”), 4 (“indeterminate” or “suspicious”), and 5 (“highly suspicious”) lesions (3%, 25%, and 95%, respectively) were within the expected ranges. Twenty malignant biopsy results were excluded from our analysis because surgical treatment was performed elsewhere (n = 12), not performed for the diagnosis of lymphoma (n = 4), or deferred because of the discovery of AJCC stage IV disease (n = 3) or by patient request (n = 1). The remaining 220 malignant lesions were surgically excised from 202 patients. The CNBx specimens of three patients who had no evidence of malignancy in their final surgical specimen were reviewed. Two lesions initially diagnosed as DCIS were reclassified as atypical ductal hyperplasia and were considered false-positive results. The third lesion was a tubular carcinoma completely removed by CNBx and was included as a true-positive result.

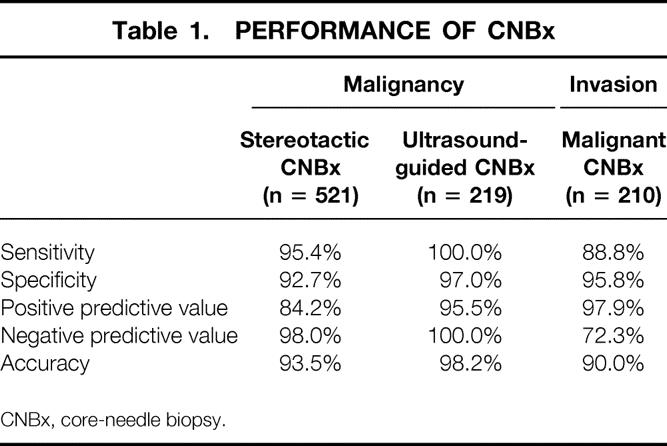

The performance of CNBx for the detection of malignancy is summarized in Table 1. For this analysis, we considered atypical hyperplasia a positive CNBx result, yielding an overall sensitivity and specificity for CNBx of 97% and 94%, respectively. The overall positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of CNBx were 88%, 98%, and 95%, respectively. We also examined the ability of CNBx to distinguish invasive from noninvasive cancers. Sixty-five malignant lesions (30%) were diagnosed as DCIS. On surgical excision, 47 of these lesions (72%) were confirmed to be noninvasive, including the two false-positive results reclassified as atypical ductal hyperplasia. In 18 of the lesions diagnosed as DCIS (28%), invasive ductal carcinoma was found in addition to DCIS. One hundred forty-five (67%) invasive malignancies were diagnosed by CNBx: invasive ductal carcinoma (n = 124), invasive lobular carcinoma (n = 14), colloid (mucinous) carcinoma (n = 3), tubular carcinoma (n = 3), and metastatic tumor of nonbreast origin (n = 1). Only four final surgical specimens had no evidence of invasive carcinoma, including the tubular carcinoma completely removed by the CNBx. Ten patients were excluded from this analysis: three patients with phylloides tumors and seven patients in whom cancerous cells were identified but could not be specified as invasive or noninvasive. Thus, the overall sensitivity and specificity of CNBx for the detection of invasion were 89% and 96%, respectively.

Table 1. PERFORMANCE OF CNBx

CNBx, core-needle biopsy.

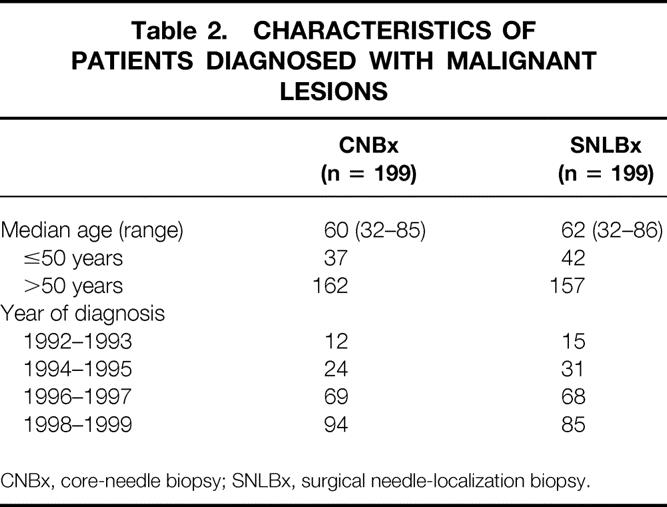

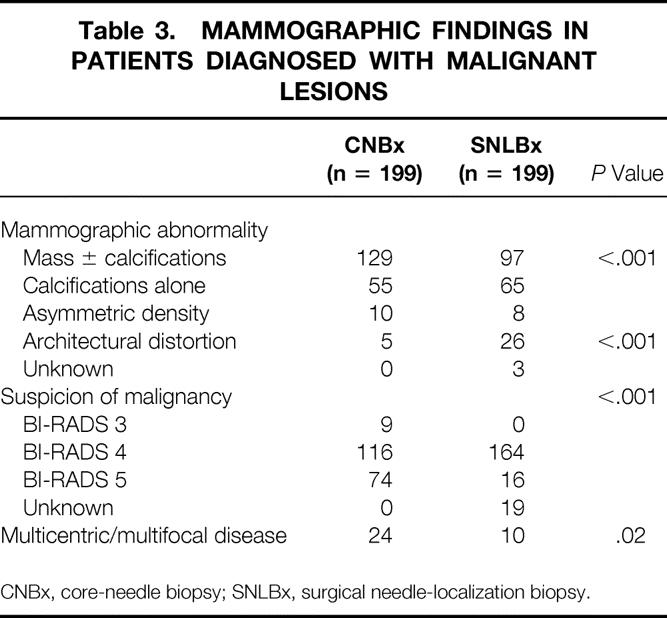

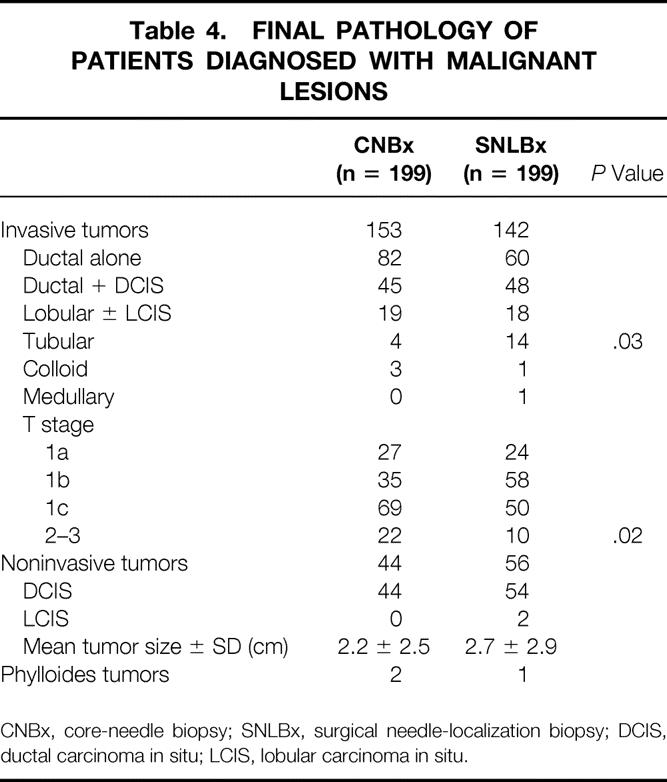

The impact of CNBx on surgical outcome was examined in 199 patients with 217 malignant primary breast lesions. Two patients with false-positive biopsy results and one patient with metastasis to the breast were excluded. An age-matched group of 199 patients with 209 primary lesions diagnosed by open SNLBx at our institution during the same period was identified for comparison. Clinicopathologic characteristics of these two groups are summarized in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS DIAGNOSED WITH MALIGNANT LESIONS

CNBx, core-needle biopsy; SNLBx, surgical needle-localization biopsy.

Table 3. MAMMOGRAPHIC FINDINGS IN PATIENTS DIAGNOSED WITH MALIGNANT LESIONS

CNBx, core-needle biopsy; SNLBx, surgical needle-localization biopsy.

Table 4. FINAL PATHOLOGY OF PATIENTS DIAGNOSED WITH MALIGNANT LESIONS

CNBx, core-needle biopsy; SNLBx, surgical needle-localization biopsy; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ.

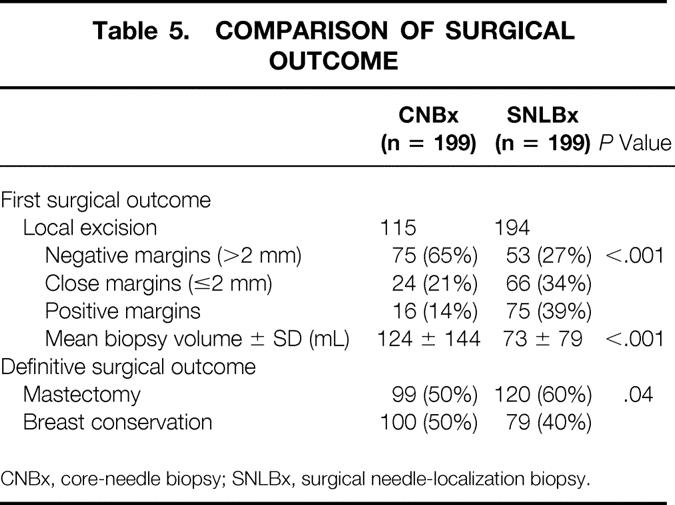

The first surgical procedure performed for patients diagnosed by CNBx was mastectomy in 84 patients (42%) and local excision in 115 patients (58%). Sentinel lymph node biopsy, axillary lymph node dissection, or both were performed in addition to local excision in 41 patients (21%). Of the 115 CNBx patients in whom local excision was attempted, 15% had positive margins and 21% had close (≤2 mm) margins (Table 5).

Table 5. COMPARISON OF SURGICAL OUTCOME

CNBx, core-needle biopsy; SNLBx, surgical needle-localization biopsy.

The first surgical procedure performed in patients evaluated by SNLBx was local excision (SNLBx with or without wide reexcision) in 194 patients (97%) and mastectomy in 5 patients (3%). Of the 194 SNLBx patients who had local excision as the initial procedure, 39% had positive margins and 34% had close margins.

Patients diagnosed by CNBx were less likely to have positive or close initial margins after local excision than patients diagnosed by SNLBx (P < .001). Patients diagnosed before surgery with malignancy had larger-volume excision specimens than patients diagnosed by SNLBx (P < .001).

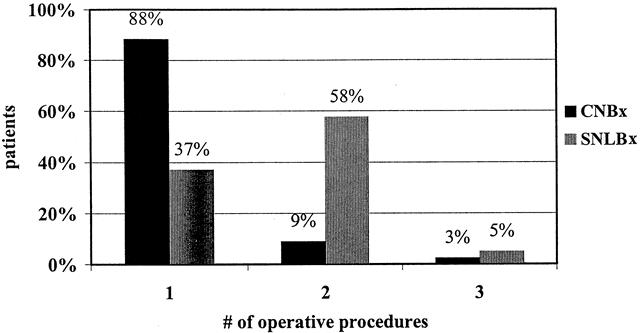

Of the patients diagnosed by CNBx, 176 (88%) had definitive treatment at the first surgical procedure (P < .001 vs. SNLBx). Twenty-three patients diagnosed by CNBx (12%) required one (n = 18) or two (n = 5) procedures for reexcision (n = 10), axillary lymph node dissection (n = 2), and/or mastectomy (n = 16) (Fig. 2). In contrast, only 74 (37%) of the patients diagnosed by SNLBx were definitively treated at the first surgical procedure. The remaining 125 patients (63%) required one (n = 115) or two (n = 10) additional trips to the operating room for reexcision (n = 55), axillary lymph node dissection (n = 17), and/or mastectomy (n = 74). On average, patients diagnosed by CNBx required 1.1 surgical procedures for definitive treatment versus 1.7 procedures for patients diagnosed by SNLBx (P < .001).

Figure 2. Number of operative procedures required for definitive treatment.

The final surgical outcomes of patients diagnosed by CNBx and SNLBx are compared in Table 5. A higher rate of successful breast conservation was observed in the patients diagnosed by SNLBx (P = .04). This difference is likely attributable to the higher incidence of multicentric disease and the greater number of T2 to 3 tumors in the group of patients diagnosed by CNBx.

DISCUSSION

Percutaneous, image-guided core-needle biopsy is a less invasive alternative to SNLBx for the diagnosis of nonpalpable mammographic abnormalities. In previous small series, CNBx has been shown to obviate the need for surgery in patients with benign lesions and to facilitate treatment for patients with breast cancer. The results of this study clearly show that CNBx reduces the incidence of positive margins after local excision and decreases the number of surgeries for definitive local treatment of breast cancer. Our results further suggest that patients with benign CNBx results may safely be observed.

Benign Results

For benign lesions, which constitute the majority of mammographic abnormalities, several advantages of diagnosis by CNBx over SNLBx are relevant. CNBx can generally be performed in less than 1 hour and often on the same day the lesion is detected. Complications, including hematoma and infection, are infrequent (0.2%). 7 Because the procedure is less invasive than SNLBx, there is less postprocedural discomfort, less disfigurement, and less distortion on future mammograms. 8

However, the value of CNBx is vitally dependent on its sensitivity for the detection of malignancy. Numerous recent studies have reported false-negative rates of 0% to 4%. 9–15 In many of these series, the false-negative rate included patients who were correctly diagnosed by early surgical excision. Similarly, in the large multiinstitutional study of CNBx by Parker et al, 7 1.1% of biopsy results were categorized as falsely negative, two thirds of which were correctly diagnosed within 6 months of CNBx. Therefore, the average miss rate of CNBx compares favorably with that of SNLBx, which was 2.6% in a recently published review of 48 series in the literature. 16

Our experience underscores the need for interpretation of negative biopsy results in the context of mammographic and clinical suspicion. If atypical hyperplasia is considered a positive result—because it is treated, as a result of the high prevalence of concurrent DCIS17—false-negative results were obtained in seven patients (false-negative rate 3%). Five of these were caught by early SNLBx on the basis of nondiagnostic CNBx (n = 3) or discordance between mammographic and pathologic results (n = 2). As a result, only two patients did not undergo timely excision, for an actual miss rate of 0.9%.

Although some surgeons use SNLBx to confirm almost all benign diagnoses by CNBx, SNLBx plays a more selective role at our institution. If specimen radiography confirms adequate sampling, most benign lesions by CNBx can safely be observed. However, close mammographic and clinical follow-up is essential. At our institution, if the histologic findings correlate with the mammographic appearance (e.g., fibroadenoma), routine annual mammographic follow-up is recommended. If the histologic findings are benign but not as definitive (e.g., fibrocystic changes), short-term (6-month) follow-up is recommended. A few recent reports have illustrated the importance of long-term follow-up of benign lesions; false-negative results were correctly diagnosed at intervals up to 36 months from CNBx. 12,13,15 These observations are supported by our findings that the two missed diagnoses in our series were correctly diagnosed at 15 and 19 months. Underestimation of false-negative results in this and in other series may be due to incomplete follow-up of patients with benign CNBx. This possibility limits the ability of this study to define the true false-negative rate of CNBx, because 35% of patients with benign biopsy results in our series had incomplete (<1 year) mammographic follow-up as a result of death from other causes, noncompliance, or changes in health care provider. Further, of patients considered to have true-negative results in our study, only 72% had surgical confirmation or mammographic follow-up of greater than 2 years.

When CNBx is nondiagnostic or the diagnosis is discordant with the mammographic appearance or clinical suspicion, SNLBx is indicated to resolve the discordance. Whether a high degree of mammographic suspicion alone (e.g., BI-RADS 5) should be an indication for SNLBx confirmation is unclear. Otherwise, for discordant results, SNLBx is considered the gold standard for confirming benign diagnoses. Although SNLBx is not perfect, the combination of CNBx and SNLBx should result in a miss rate lower than with either technique alone. With the selective use of SNLBx to confirm discordant results and close follow-up, most false-negative CNBx results will not lead to missed diagnoses.

Malignant Results

For malignant lesions, CNBx can reliably establish a diagnosis before surgery. The specificity and positive predictive value of CNBx for the detection of malignancy approached 100% in our series, as in others. 7,10,18 The rarity of false-positive results allows definitive treatment decisions to be made on the basis of CNBx results alone in virtually all patients. When false-positive results do occur, they are difficult to distinguish from true malignant lesions that were completely removed at the time of CNBx, which are more common with larger-gauge needles and vacuum-assisted techniques. 19,20 In our series, the only two false-positive results were biopsies interpreted initially as DCIS and as atypical ductal hyperplasia on retrospective review. Wide local excision was appropriate for these patients, because surgical removal is required for a CNBx diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia.

In addition to the diagnosis of malignancy, CNBx provides additional information regarding the presence of microscopic invasion (i.e., invasive cancer vs. DCIS). In our series, CNBx was highly specific for invasive carcinoma, and the positive predictive value of CNBx was 98%. False-positive results for invasion, like those for malignancy, were rare and difficult to distinguish from the complete removal of true microinvasive components by CNBx. Conversely, 28% of lesions diagnosed as DCIS by CNBx were underestimated and found to have invasive components on surgical excision. Thus, treatment discussions based on the preoperative diagnosis of DCIS should include the possible need for subsequent axillary lymph node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy.

In addition to diagnosis, CNBx generally provided adequate tissue for determination of histologic grade, vascular and lymphatic invasion, estrogen and progesterone receptor status, and the presence of molecular tumor markers such as Her-2/neu. For some surgeons and patients, these or other prognostic variables may weigh into such decisions as whether to attempt breast-conservation therapy, 21,22 use sentinel lymph node biopsy, or perform axillary lymph node dissection. 23 Prospective information afforded by CNBx clearly facilitates complex treatment planning.

Surgical Management

Our results corroborate those of previous smaller series showing the advantages of CNBx in the surgical treatment of breast cancer. Yim et al 4 retrospectively compared 21 patients with invasive breast cancer diagnosed by CNBx with 31 unmatched patients diagnosed by SNLBx. In their series, patients diagnosed by SNLBx were more likely than patients diagnosed by CNBx to have positive surgical margins (55% vs. 0%) after the first surgical procedure, although two thirds of CNBx patients in this underwent mastectomy. None of the seven CNBx patients who received breast-conserving therapy required reexcision, and the reduced number of surgical procedures corresponded to a significant cost savings. In a more recent series of 58 patients diagnosed before surgery by CNBx, 77% were definitively treated in one surgical procedure, and the incidence of positive margins after wide local excision was 31%. 24

In our series, CNBx allowed planning of definitive surgical treatment before surgery, which produced more efficient use of operating room resources. More than 40% of patients diagnosed before surgery proceeded directly to mastectomy. In these patients, the cost of CNBx was partially offset by avoidance of mammographic needle localization before surgery. Another 21% of patients underwent axillary lymph node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy during the first surgical procedure, reducing the likelihood of subsequent return to surgery.

Among patients in whom local excision was performed as the first surgical procedure, negative margins (>2 mm) were obtained in 65% of patients diagnosed by CNBx and 27% of patients diagnosed by SNLBx. The higher rate of negative margins likely resulted from the larger excision specimen size of patients diagnosed before surgery than patients without a cancer diagnosis at the time of excision. It seems intuitive that if the lesion is known to be cancer, the surgeon is more willing to create, and the patient is more willing to accept, a larger breast defect. The performance of mastectomy, the management of axillary lymph nodes, and the more adequate local excision of tumors during the first surgical procedure translated to fewer total procedures for patients diagnosed by CNBx. This difference was significant not only for patients managed with mastectomy (1.2 vs. 2.0, P < .001) but also for those successfully managed with breast-conserving therapy (1.1 vs. 1.4, P < .001).

Preoperative diagnosis facilitated planning of procedures that required coordination of multiple personnel, such as sentinel lymph node biopsy and breast reconstructive procedures. Sentinel lymph node biopsy requires preoperative injection of radiocolloid for lymphoscintigraphy. Further, CNBx may be the optimal biopsy technique for sentinel lymph node biopsy candidates because it causes less disruption of the surrounding lymphatics, with better flow of radiocolloid to the sentinel lymph node. 25 Immediate breast reconstruction with myocutaneous flaps and staged reconstruction with the implantation of tissue expanders and saline prostheses do not interfere with adjuvant therapy and have been associated with excellent esthetic results 26,27 and less expense than delayed reconstruction. 28 Sixteen patients diagnosed before surgery by CNBx underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy, and five patients underwent the first stage of breast reconstruction during the first surgical procedure.

Certainly, any comparison between nonrandomized groups is limited by selection bias. At our institution, patients diagnosed by SNLBx were older, and more SNLBx patients were diagnosed early in the study period than patients diagnosed by CNBx. Although these differences were minimized by selection of a control group matched for age and year of diagnosis, other differences remain. Patients diagnosed by CNBx had larger invasive tumors and a higher incidence of multicentric disease than patients diagnosed by SNLBx. Patients diagnosed by CNBx were more likely to have a mass abnormality and were less likely to have architectural distortion on mammography. Other factors related to lesion location, breast size, or patient medical condition likely differed between the two groups but were not compared in this study.

Cost-Effectiveness

Finally, numerous studies have shown CNBx to be a cost-effective technique. 4,29–31 However, the cost-effectiveness of CNBx for each institution will vary with biopsy technique, experience with mammographic–histologic correlation, patient compliance with follow-up, and surgical management of early breast cancer. Typical total charges at our institution (hospital + professional) are $1,900 for stereotactic CNBx and $1,500 for ultrasound-guided CNBx. By comparison, total charges for SNLBx, including mammographic needle localization and open surgical biopsy, are approximately $5,000. The cost savings of greater than $2,000 for each lesion diagnosed as benign by CNBx should outweigh the cost of the 12% of benign results that required confirmation by surgical excision. These cost savings should be further enhanced by the 35% fewer surgical procedures required for patients diagnosed with malignant lesions by CNBx than for patients diagnosed by SNLBx.

CONCLUSIONS

Core-needle biopsy should be considered the first diagnostic test for all patients with indeterminate or suspicious mammographic abnormalities (BI-RADS 4 or 5) as well as for patients with benign or probably benign mammographic abnormalities (BI-RADS 2 or 3) who cannot be followed up reliably by mammography. For most patients, CNBx provides a benign diagnosis without a surgical procedure. Missed diagnoses are rare with selective use of SNLBx to confirm discordant results. For patients with malignant lesions, CNBx decreases the waiting interval between hearing that they have an abnormal mammogram and knowing whether and what therapy is needed. CNBx allows definitive treatment decisions to be made before surgery, facilitates excision with adequate surgical margins, and reduces the number of surgical procedures required for treatment. CNBx is an accurate and cost-effective technique that improves the care of patients with both benign and malignant mammographic abnormalities. 17

Discussion

Dr. J. Dirk Iglehart (Boston, Massachusetts): I am glad to discuss a procedure that is now already 10 years old rather than a procedure that has only been around for a year or so.

At my institution, the Brigham Women’s Hospital in Boston, we have a similar experience with core-needle biopsy. It’s used liberally for the diagnosis and management of indeterminate mammographic abnormalities, and recently published on about 1,800 core biopsies done since 1991, and, interestingly, with a malignancy rate of 22%, which agrees very well with your 23%. Investigators at the Brigham Women’s Hospital also found, as you did, that the use of core-needle biopsy resulted in fewer surgical procedures. And that is, I think, important. The average patient nowadays with breast cancer probably has somewhere between two and three surgical procedures, which both for the surgeon and for the patient seems excessive. I have a couple of questions.

The first question concerns the rate of breast-conserving surgery in the patients who receive needle-localized biopsy. Actually, the number of patients who were able to be conserved was higher in the group that was initially diagnosed by needle-localized biopsy, I believe, in your data, which is hard to understand why that would be. It seems that the two groups should be pretty comparable.

The second question concerns the overall approach to core biopsy. It seems like everything that walks in the door gets cored nowadays, and one wonders whether or not—the way we used to do it was a 6-month follow-up. You know, who should be offered a 6-month follow-up rather than a core biopsy?

Thanks. I enjoyed your paper very much, and I do appreciate the chance to have read it previously. Thanks.

Dr. Craig L. Slingluff (Charlottesville, Virginia): Thank you, President Aust, Secretary Townsend, members, and guests. I appreciate also Dr. Seigler and Dr. White sending the manuscript. They are to be congratulated on a very nice paper. It is important for these types of procedures that are rapidly changing the way that we manage cancer patients from a surgical standpoint. It is important that they be evaluated systematically like this so that we learn where there are ways that we continue to improve them. And they are to be congratulated on this nice review.

I had a couple of comments. I think it is arguable that one of the most important diagnoses to be made accurately is the diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. Certainly, one of the points that is reiterated in this paper is that there is a continuum between atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. And this sampling of ductal carcinoma in situ by core biopsy can sometimes lead to the impression of atypical hyperplasia. And it has been appropriately shown here, as our group has previously reported by Dr. Moore, that somewhere between 20% and 50% of patients with atypical hyperplasia, on subsequent excision, are actually found to have ductal carcinoma in situ.

However, one surprise in this report is that there were a couple of patients who were reported as having ductal carcinoma in situ, amounting to 3% of DCIS diagnoses, who on subsequent excision had the diagnosis changed, downgraded to atypical ductal hyperplasia. And I’d be interested in comments on how that may be occurring.

A second observation is that 18 of 64 diagnoses of ductal carcinoma in situ, or 28%, were found to be associated with invasive disease. This is not particularly different, I think, from the experience that we have had or probably others have had, and it is not surprising. But I’d be interested in the proportion of those that are microinvasive and how often this has led to subsequent evaluation of draining nodes. In particular, I think, as we look over the ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis, then we are talking about probably about 30% or a third of these where there is a change in the diagnosis once excision is made.

One of the approaches for management of DCIS, of course, is mastectomy, but that would be an overaggressive procedure if it is not really DCIS, and it would prevent going back and doing a sentinel node biopsy. So I wonder if we should change our surgical approach in patients who have DCIS on a basis of core biopsy alone.

A second minor question is that a substantial point of the study is that there was a difference in the margins, the rate of positive margins, after core biopsy diagnosis as opposed to a needle-localized biopsy diagnosis. And since the needle-localized biopsy is really intended as a diagnostic procedure rather than a therapeutic one, I’m wondering if it is really an entirely appropriate point to make.

Certainly, the final conclusion, which is a very important one is—and it supports the continuation of this approach—is that the number of surgical procedures is diminished by using it.

Again, I congratulate the authors on a very nice paper.

Dr. David S. Robinson (Kansas City, Missouri): I rise to congratulate the authors on a wonderful paper. I do have a couple of questions, though, and an observation.

Since 1991 to 1992 until the present, the technology has changed dramatically. We have moved from analog, which takes about six and a half minutes, to digital pictures which come up in about two and a half seconds, shortening the time. And at the same time, we have moved from using 14-gauge Tru-cut with a spring to the vacuum-assisted device.

Did the authors find that there was less DCIS in the vacuum-assisted patients who were seen since about the last 5 years as opposed to those who had Tru-cuts?

And with regard to taking patients back to the operating room, would that decrease the number of cases that you would have to take back to the operating room if you were to use the vacuum-assisted device today?

In addition, the three false positives: one of those shows that there was no tumor left. I submit as we use more vacuum-assisted biopsies which are contiguous cores, which can take out an area of about 1.5 cm, we will probably find a fair number of patients who have no tumor left, but I don’t think that poses a problem. Thank you.

Dr. R. Phillip Burns (Chattanooga, Tennessee): I enjoyed this paper, and I’m happy to see it presented in this form. I do have a couple of questions, the same question that I had earlier for Dr. Moore. Who did the biopsy? How is your service organized in terms of the decision for that? Who follows the patient with the benign diagnosis? In other words, whose responsibility is it going to be when there is that rare false negative? Along those lines, do you have any ideas about what is the optimal organization, both in large medical centers and in smaller institutions?

Thank you.

Dr. Don M. Morris (Albuquerque, New Mexico): Dr. Aust, Dr. Townsend.

I’d also like to know who did the biopsy and who decides to do the biopsy and also who notifies the patient of the results of the biopsy. I work in a large medical center where we have a lot of indigent patients, and we see people referred in on contract, and we have had problems with them falling through the cracks. And how you prevent that, I’d like to know. Thank you.

Dr. Rebekah White (Durham, North Carolina): I’d like to thank Dr. Iglehart and Dr. Slingluff as well as the other discussants for their comments. We’d like to thank President Aust and Secretary Townsend for the opportunity to address those comments. I will try to answer them in order.

First, in response to Dr. Iglehart’s question, I think it is important not to take away the message that core-needle biopsy leads to lower rates of breast conservation. It is true in our series that a slightly lower percent of patients diagnosed by core-needle biopsy had successful breast conservation, 50% versus almost 60%. We feel that there is a difference that is due to the nature of the retrospective comparison. Our two groups differed in several ways. For one thing, the core-needle biopsy group had a larger mean invasive tumor size and a significantly higher incidence of multicentric disease. And we think that this largely explains the difference in the rate of breast conservation.

With regard to your question about who should not get core-needle biopsy, there have been a number of studies done addressing the cost-effectiveness of core-needle biopsy, and it has been show that it is not cost effective, for instance, for BI-RADS 3 or probably benign lesions to be biopsied, because the rate of malignancy is so low, usually less than 5%. However, you have to individualize that decision. A patient with a BI-RADS 3 lesion has either a high clinical suspicion or has a high level of anxiety. Those patients may be better managed with core-needle biopsy.

Dr. Slingluff raised several points about the use of a core-needle biopsy diagnosis of DCIS. In our series, our only two false positives were patients who had core-needle biopsy diagnosis of DCIS. On surgical excision, no evidence of malignancy was found. On review of those core-needle biopsy specimens, the diagnosis was felt to have been misclassified and was more appropriately classified as atypical ductal hyperplasia. Fortunately, both of those patients were treated with local excision, and so they were treated appropriately for atypical ductal hyperplasia as well. We do not think this is entirely due to good luck. As Dr. Slingluff mentioned, DCIS is a continuum, even though we tend to lump it into categories. For instance, if the DCIS seen on the core-needle biopsy is high grade and has clear evidence of necrosis, I think one could proceed with confidence to mastectomy if that was the chosen course of treatment.

Conversely, as was probably the case in our two false positives, if the diagnosis is more subtle, such as involving only a few ducts, then perhaps it is more prudent to proceed conservatively until the diagnosis can be confirmed.

A second point he made was regarding our comparison of margins after first excision in patients diagnosed by core-needle biopsy and patients in the process of being diagnosed by surgical needle-localization biopsy. I agree that this may not be a fair comparison, in that the intents are different with those two procedures. The intent after core-needle biopsy is purely therapeutic. Your diagnosis is already established, whereas the intent of the first excision for needle-loc biopsy is primarily diagnosis, but I believe a secondary goal of most surgeons performing a needle-loc excision is to try to establish clear margins and avoid a second trip to the operating room. Perhaps a more fair comparison would have been to only compare patients in whom the surgeon felt that there was sufficient suspicion based on clinical or mammographic appearance that he or she was trying to achieve negative margins with the needle-loc biopsy.

With regard to Dr. Robinson’s question regarding the evolving techniques. We did not specifically examine the incidence of DCIS in early versus late patients. I did, however, look at rates of sensitivity. And as has been shown in other studies, the vacuum-assisted technique was marginally more sensitive for detecting both malignancy and invasion than the multipass or hand-automated technique. And we agree that complete removal of a lesion, as is going to become more common with these vacuum-assisted techniques, should not be considered a false positive, and we did not in our series.

Finally, Dr. Burns’ and Dr. Morris’s questions relate to who should be doing this and how we should be managing the results. At our institution, radiologists perform this procedure. And I understand that that is a very controversial issue at other centers. We do feel, though, that it remains the surgeon or the primary physician’s responsibility to follow up those results and to notify those patients.

Thank you.

Footnotes

Presented at the 112th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 4–6, 2000, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Hilliard F. Seigler, MD, DUMC Box 31118, Durham, NC 27710. Reprint reaquests: Hilliard F. Seigler, MD, DUMC Box 3966, Durham, NC 27710.

E-mail: rrw1@duke.edu.

Accepted for publication December 2000.

References

- 1.Tabar L, Fagerberg CJ, Gad A, et al. Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography. Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet 1985; 1: 829–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cyrlak D. Induced costs of low-cost screening mammography. Radiology 1988; 168: 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberman L. Clinical management issues in percutaneous core breast biopsy. Radiol Clin North Am 2000; 38: 791–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yim JH, Barton P, Weber B, et al. Mammographically detected breast cancer. Benefits of stereotactic core versus wire localization biopsy. Ann Surg 1996; 223: 688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee CH, Egglin TK, Philpotts L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of stereotactic core needle biopsy: analysis by means of mammographic findings. Radiology 1997; 202: 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman CS, Delbecq R, Jacobson L. Excising the reexcision: stereotactic core-needle biopsy decreases need for reexcision of breast cancer. World J Surg 1998; 22: 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker SH, Burbank F, Jackman RJ, et al. Percutaneous large-core breast biopsy: a multi-institutional study. Radiology 1994; 193: 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaye MD, Vicinanza-Adami CA, Sullivan ML. Mammographic findings after stereotaxic biopsy of the breast performed with large-core needles. Radiology 1994; 192: 149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitre B, Baron PL, Baron LF, et al. Stereotactic core biopsy of the breast: results of one-year follow-up of 101 patients. Am Surg 1997; 63: 1124–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuhrman GM, Cederbom GJ, Bolton JS, et al. Image-guided core-needle breast biopsy is an accurate technique to evaluate patients with nonpalpable imaging abnormalities. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 932–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer JE, Smith DN, Lester SC, et al. Large-needle core biopsy: nonmalignant breast abnormalities evaluated with surgical excision or repeat core biopsy. Radiology 1998; 206: 717–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CH, Philpotts LE, Horvath LJ, et al. Follow-up of breast lesions diagnosed as benign with stereotactic core-needle biopsy: frequency of mammographic change and false-negative rate. Radiology 1999; 212: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackman RJ, Nowels KW, Rodriguez-Soto J, et al. Stereotactic, automated, large-core needle biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions: false-negative and histologic underestimation rates after long-term follow-up. Radiology 1999; 210: 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan JL 3rd, Cederbom GJ, Champaign JL, et al. Benign diagnosis by image-guided core-needle breast biopsy. Am Surg 2000; 66: 5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns RP, Brown JP, Roe SM, et al. Stereotactic core-needle breast biopsy by surgeons: minimum 2-year follow-up of benign lesions. Ann Surg 2000; 232: 542–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackman RJ, Marzoni FA, Jr. Needle-localized breast biopsy: why do we fail? Radiology 1997; 204: 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore MM, Hargett CW 3rd, Hanks JB, et al. Association of breast cancer with the finding of atypical ductal hyperplasia at core breast biopsy. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 726–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer JE, Smith DN, Lester SC, et al. Large-core needle biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions. JAMA 1999; 281: 1638–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burbank F. Stereotactic breast biopsy of atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ lesions: improved accuracy with directional, vacuum-assisted biopsy. Radiology 1997; 202: 843–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberman L, Smolkin JH, Dershaw DD, et al. Calcification retrieval at stereotactic, 11-gauge, directional, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. Radiology 1998; 208: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yaghan R, Stanton PD, Robertson KW, et al. Oestrogen receptor status predicts local recurrence following breast conservation surgery for early breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 1998; 24: 424–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalberg K, Eriksson E, Kanter L, et al. Biomarkers for local recurrence after breast-conservation: a nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 57: 245–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindahl T, Engel G, Ahlgren J, et al. Can axillary dissection be avoided by improved molecular biological diagnosis? Acta Oncol 2000; 39: 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cangiarella J, Gross J, Symmans WF, et al. The incidence of positive margins with breast conserving therapy following mammotome biopsy for microcalcification. J Surg Oncol 2000; 74: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pijpers R, Meijer S, Hoekstra OS, et al. Impact of lymphoscintigraphy on sentinel node identification with technetium-99m-colloidal albumin in breast cancer. J Nucl Med 1997; 38: 366–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelin K, Billgren AM, Wickman M. Management, morbidity, and oncologic aspects in 100 consecutive patients with immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 1998; 5: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spear SL, Majidian A. Immediate breast reconstruction in two stages using textured, integrated-valve tissue expanders and breast implants: a retrospective review of 171 consecutive breast reconstructions from 1989 to 1996. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 101: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoo A, Kroll SS, Reece GP, et al. A comparison of resource costs of immediate and delayed breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 101: 964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fajardo LL, DeAngelis GA. The role of stereotactic biopsy in abnormal mammograms. Surg Oncol Clin North Am 1997; 6: 285–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burkhardt JH, Sunshine JH. Core-needle and surgical breast biopsy: comparison of three methods of assessing cost. Radiology 1999; 212: 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberman L, Sama MP. Cost-effectiveness of stereotactic 11-gauge directional vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000; 175: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]