Abstract

Objective

To report the results from one of the eight original U.S. centers performing laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding (LASGB), a new minimally invasive surgical technique for treatment of morbid obesity.

Summary Background Data

Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding is under evaluation by the Food & Drug Administration in the United States in an initial cohort of 300 patients.

Methods

Of 37 patients undergoing laparoscopic placement of the LASGB device, successful placement occurred in 36 from March 1996 to May 1998. Patients have been followed up for up to 4 years.

Results

Five patients (14%) have been lost to follow-up for more than 2 years but at last available follow-up (3–18 months after surgery) had achieved only 18% (range 5–38%) excess weight loss. African American patients had poor weight loss after LASGB compared with whites. The LASGB devices were removed in 15 (41%) patients 10 days to 42 months after surgery. Four patients underwent simple removal; 11 were converted to gastric bypass. The most common reason for removal was inadequate weight loss in the presence of a functioning band. The primary reasons for removal in others were infection, leakage from the inflatable silicone ring causing inadequate weight loss, or band slippage. The patients with band slippage had concomitant poor weight loss. Bands were removed in two others as a result of symptoms related to esophageal dilatation. In 18 of 25 patients (71%) who underwent preoperative and long-term postoperative contrast evaluation, a significantly increased esophageal diameter developed; of these, 13 (72%) had prominent dysphagia, vomiting, or reflux symptoms. Of the remaining 21 patients with bands, 8 currently desire removal and conversion to gastric bypass for inadequate weight loss. Six of the remaining patients have persistent morbid obesity at least 2 years after surgery but refuse to undergo further surgery or claim to be satisfied with the results. Overall, only four patients achieved a body-mass index of less than 35 and/or at least a 50% reduction in excess weight. Thus, the overall need for band removal and conversion to GBP in this series will ultimately exceed 50%.

Conclusions

The authors did not find LASGB to be an effective procedure for the surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Complications after LASGB include esophageal dilatation, band leakage, infection, erosion, and slippage. Inadequate weight loss is common, particularly in African American patients. More study is required to determine the long-term efficacy of the LASGB

Obesity is a serious health problem in the United States, with more than 20% of the adult population affected. 1 An estimated 32.6 million Americans are overweight and 11.5 million are morbidly obese. 1,2 Significant complications occur with severe obesity, including diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol levels, cardiovascular disease, cholelithiasis, renal disease, arthritis, sleep apnea, and psychosocial problems. 3 More than 5% of the total health care costs in the United States is consumed yearly in the care of obesity-related illness. 4

Obesity treatments include diet and surgical therapy. Dieting has poor long-term results: only 10% to 20% of people who lose a considerable amount of weight can maintain that weight loss for more than a few years. 2 Surgery has been the only method proven effective in maintaining long-term weight loss. 1,5 Current methods include the gastric bypass, vertical banded gastroplasty, and gastric banding, as well as several malabsorptive procedures. The gastric bypass (GBP) was introduced in 1966 by Mason, followed by development of the vertical banded gastroplasty in 1980. 6 Silicone gastric banding was first performed in January 1983 and became adjustable in 1986. 7 Patient acceptance of the GBP and similar procedures has been limited because of the invasiveness of the procedure, with its concurrent risks. Therefore, efforts to find safer, more effective, less morbid, and more widely accepted methods of surgical weight loss continue.

Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding (LASGB) is a surgical technique for the treatment of obesity that has become popular in many countries in recent years, and more than 50,000 of these devices have been implanted, especially in Europe and Australia, where large series have been reported suggesting the device is safe and effective. 8,9 Reported complications of gastric banding include stoma obstruction, band erosion, pouch dilatation, and band slippage. 10–16 In the United States, LASGB is being evaluated in a multicenter clinical trial supervised by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in an initial cohort of 300 patients. Seven United States centers, as well as an eighth center in which the device was placed by an open surgical technique, participated in the so-called A Trial, which included our institution.

We present our institution’s experience with the LASGB procedure, which raises major concerns about inadequate long-term weight loss. In addition, we have identified a new long-term complication, dilatation of the esophagus, that carries an unclear significance but demands further scrutiny.

METHODS

Thirty-seven patients underwent surgery for placement of an LASGB (BioEnterics Corp., Carpinteria, CA) for the treatment of morbid obesity. Procedures were performed by three surgeons with extensive bariatric surgical experience (H.J.S., J.M.K., E.J.D.), but the 37 procedures reported here, beginning in 1996, were the first of any kind attempted by the group for the laparoscopic treatment of obesity. Thus, the current report comprises our early learning curve experience for this procedure. Training for the laparoscopic procedure included a site visit with on-site supervised performance of four procedures in conjunction with an experienced surgeon as proctor, who has published his extensive personal experience with this procedure. 17

Patients were evaluated before surgery in a bariatric surgical clinic that primarily offered GBP to morbidly obese patients using an open technique. 18 Patients accepted for the LASGB procedure included those specifically requesting this procedure, patients with a preoperative body-mass index (BMI) less than 50 kg/m2, patients with no or limited previous abdominal surgery, and patients in whom dietary screening did not reveal significant (>10%) calorie intake in the form of sweets. This latter entry criterion was based on previous data showing a high failure rate for patients who were considered to be “sweets eaters” undergoing vertical banded gastroplasty for obesity. 18, 19 This represented a more restrictive selection criteria than other institutions in the FDA trial.

Patients underwent a detailed informed consent process approved by our institutional review board. Preoperative upper gastrointestinal barium radiographs were obtained to evaluate baseline gastrointestinal anatomy. The band was placed using a five-port laparoscopic technique. 17 The perigastric dissection was undertaken with electrocautery high on the lesser curvature of the stomach. A balloon catheter (calibration tube, BioEnterics Corp.) inserted through the mouth and advanced into the stomach was inflated with 15 mL saline and pulled back to lodge at the gastroesophageal junction to size the proximal pouch approximately. Dissection was begun at the balloon’s equator to keep the dissection above the free lesser sac on the posterior aspect of the stomach to reduce posterior band slippage. The band device was closed overlying a pressure-sensitive location on the calibration tube to determine correct positioning and to avoid too much tissue within the band. Saline was then injected into the band to determine the maximal fill volume for each device based on intraluminal pressure measurements from the gastrostenometer device. Three or four anterior sutures between the pouch and the distal stomach were placed to prevent anterior band slippage. In our initial experience, the band was left filled with half the maximal fill volume. In later cases, at the recommendation of BioEnterics Corp., the band was left empty for 1 month after surgery in an attempt to decrease early postoperative band slippage.

Patients were followed up by their surgeon and dietitian at frequent postoperative intervals to assess weight loss, percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), percentage of ideal body weight (%IBW) achieved, and band tolerance. Saline was added to the band reservoir under fluoroscopic guidance according to patient’s weight loss and satiety. Serial upper gastrointestinal barium radiographs were obtained during an average of 20 months of follow-up. We performed band adjustments under fluoroscopic guidance after contrast evaluation in patients who were not losing weight adequately. During follow-up, we realized that many radiographs were showing esophageal dilatation. In eight patients, saline was injected into the bands of patients with inadequate weight loss despite the presence of mild esophageal dilatation on a contrast examination. Once the complication of esophageal dilatation was more completely recognized, fluid was removed from the band when this diagnosis was made.

Retrospectively, preoperative and multiple postoperative upper gastrointestinal barium radiographs were reviewed, and those showing maximal esophageal dilatation were selected. The esophageal diameter was measured in millimeters proximal to the esophageal ampulla. The gastric band diameter and vertebral height were used as an internal control to account for variable film magnification. 20 Reports were reviewed for comments on dysmotility. A chart review was also undertaken to correlate symptoms with esophageal dilatation and dysmotility. Complete data were available on 24 patients, plus 1 additional patient who underwent surgery at another center but was followed up by us. The esophagus was considered dilated when the diameter on follow-up films was 130% or more of that on the baseline preoperative film.

Data are provided as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by paired and unpaired t tests as appropriate, with significance set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Of 37 patients undergoing laparoscopic placement of the LASGB device, it was placed successfully in 36 between March 1996 and May 1998. One patient had intraoperative perforation of the stomach during the dissection and underwent open conversion and proximal gastric bypass because it was unsafe to place the band over the gastric repair site. Patients have been followed up for up to 4.5 years. Five patients (14%) have been lost to follow-up for 2 years or more from the time of surgery.

The average age of patients was 38.9 ± 8.9 years (range 23–53). Only three men (8%) underwent LASGB. Eight patients (22%) were African American; the rest were white. Table 1 shows the preoperative and postoperative body weight data. The average preoperative BMI was 44.5 kg/m2; it decreased to 35.8 kg/m2 at 36 months of follow-up. Average weight loss per patient was 18.4 kg, and the percentage of excess weight lost was 38.4% at 36 months.

Table 1. PREOPERATIVE AND POSTOPERATIVE BODY WEIGHT DATA

BMI, body-mass index; EWL, excess weight loss. Results (± S.D.) are given at the most recent available follow-up. Weight loss results in the top section exclude results in patients who underwent band removal or conversion to gastric bypass; these patients are shown in the lower section of the table. The excess weight loss in patients undergoing band removal for any reason is reported in patients undergoing band removal during each 12-month interval (number in parentheses).

The LASGB devices were removed in 15 (41%) patients 10 days to 42 months after surgery. The most common reason for removal was inadequate weight loss in the presence of a functioning band (n = 6). This group lost a mean of only 21% of excess weight between 18 and 37 months after surgery. The primary reasons for removal in the others were infection (n = 2); leakage of injected saline from the device, causing inadequate weight loss (n = 2); or band slippage (n = 3). In both cases of band leakage, the leak was ultimately proven to be in the gastric portion of the device rather than in the tubing. Injury to the device at the time of surgical implantation as a result of needle puncture (suggested by analysis of the explanted band device in one patient) or other errors in surgical technique may have been the cause of these band leaks. Thus, band removal rather than reservoir or tubing replacement or repair was necessary. The patients with band slippage had concomitant poor weight loss (11–23% EWL).

African American patients had poor weight loss with LASGB compared with whites. The two racial groups had no significant differences in preoperative body weight, percentage of ideal weight, or BMI. However, the postoperative percentage decrease in excess body weight and weight lost were significantly less in African Americans (Table 2) at 12, 24, and 36 months.

Table 2. WEIGHT LOSS PARAMETERS BY RACE

EWL, excess weight loss.

*P < .05.

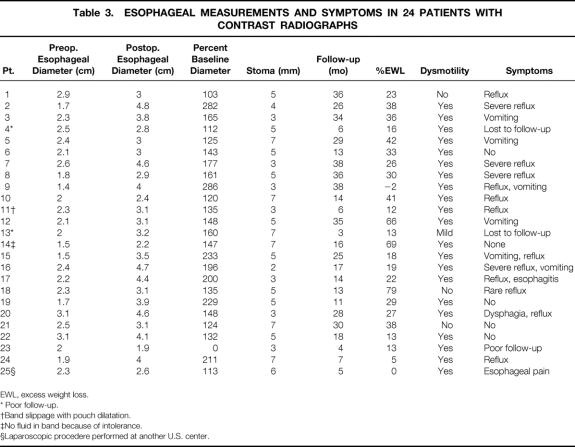

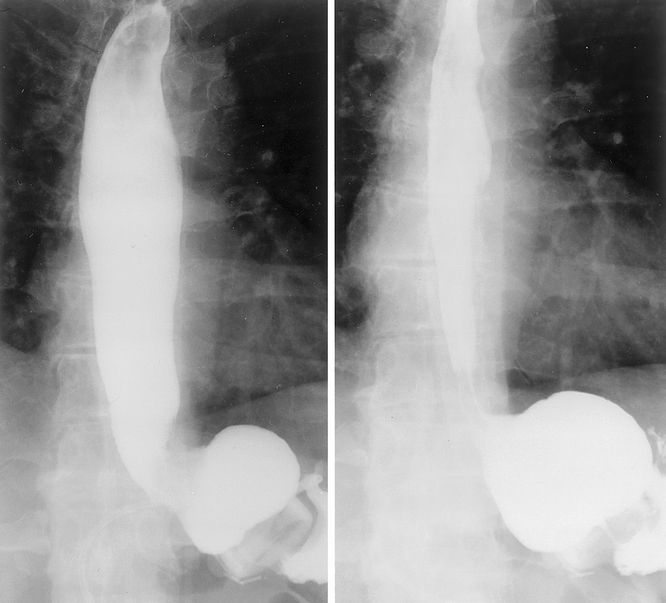

Bands were removed in two patients as a result of symptoms related to esophageal dilatation. Data regarding esophageal dilatation, symptoms, and weight loss are presented in Table 3. Eighteen of 25 patients (71%) who had both preoperative and postoperative studies had a postoperative esophageal diameter an average of 182% ± 11.5 (range 100–286%) of the baseline diameter over an average period of 21 ± 2.8 months. Stoma diameter and amount of weight loss did not correlate with the degree of esophageal dilatation. The mean preoperative esophageal diameter was 2.2 ± 0.1 cm (range 1.4–3.1), which increased after surgery to 3.3 ± 0.1 cm (range 1.9–4.8) (P < .001). Two patients who came to our clinic with esophageal dilatation and resulting symptoms had their silicone bands inserted at other institutions (Mt. Sinai, NY, and New Jersey). One of these procedures had been performed laparoscopically and this case was therefore included in our analysis (Patient 25, Table 3). Pre- and postoperative esophagograms in a patient with esophageal dilatation as a complication of LASGB are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Saline was removed from the reservoir, which only minimally decreased the degree of dilatation (Fig. 3). Eleven patients had delayed esophageal emptying, five had decreased motility, and seven had both. Of the patients with significant dilatation, 12 of 17 were symptomatic with dysphagia, vomiting, or severe reflux (see Table 3). Five of six patients with the greatest postoperative esophageal dilatation (≥200% of baseline diameter) were symptomatic. Two patients had pouch dilatation. Of the seven patients who were not significantly dilated, six had short-term follow-up, with radiographs done only 13 ± 4.2 months after surgery.

Table 3. ESOPHAGEAL MEASUREMENTS AND SYMPTOMS IN 24 PATIENTS WITH CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHS

EWL, excess weight loss.

* Poor follow-up.

†Band slippage with pouch dilatation.

‡No fluid in band because of intolerance.

§Laparoscopic procedere performed at another U.S. center.

Figure 1. Preoperative esophagogram. Diameter midesophagus measured at 2 cm.

Figure 2. Esophagogram 2 years after surgery showing esophageal and gastric pouch dilatation. Diameter midesophagus (left) 4.8 cm; pouch diameter 8 cm.

Figure 3. Esophagogram after removal of 1 mL fluid from the band. Diameter at midesophagus decreased to 4.5 cm; no persistent pouch dilatation was seen.

In eight patients, the band was tightened despite the presence of varying degrees of esophageal dilatation noted on the preadjustment contrast esophagogram. Each of these patients was adjusted before July 1999 and had inadequate weight loss; thus, the band was tightened to enhance weight loss. In July 1999 we reviewed our data, recognized the high incidence of esophageal dilatation in laparoscopically banded patients, and therefore altered our adjustment strategy. From that point forward, bands were not tightened in patients with dilatation of the esophagus. Fluid was not removed from a few of these patients because of inadequate weight loss. Patients with significant dilatation and inadequate weight loss were offered surgical treatment by conversion to proximal GBP. Of the eight patients who underwent tightening of the band despite dilatation of the esophagus, inadequate weight loss combined with dilatation led to proximal GBP conversion in five patients to date, with one awaiting insurance authorization for conversion.

Two patients were converted to GBP at 5 months and at 36 months after surgery for failed weight loss without esophageal dilatation. Three other patients had band removal and conversion to GBP for esophageal dilation, poor weight loss, and esophageal dysmotility, one each at 30, 39, and 42 months. One patient had all the fluid removed from the reservoir and two others had 1 mL removed; there was a decrease in esophageal diameter in two of these patients. The band was subsequently removed in one of these patients and the patient was converted to GBP.

Of the 15 patients undergoing band removal, 4 requested only simple device removal and 11 were converted to proximal GBP. Of the remaining 21 patients with bands in situ, 5 (14%) have been lost to follow-up for 2 or more years but at last available follow-up (3–18 months after surgery) had achieved only 5% to 38% EWL. Six patients overall currently desire removal and conversion to GBP for inadequate weight loss in the presence of a functioning band. Four of these are awaiting insurance company approval for the revisional surgery. Six additional patients have persistent severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35) at least 2 years after surgery but either refuse to undergo further surgery or are satisfied with the results.

Overall, only four patients (11%) in our series achieved BMI < 35 and/or at least a 50% reduction in excess weight without complications. Two patients without complications have had outstanding weight loss results, losing 79% and 85% of excess weight, where they remain at 113% and 117% of ideal weight, respectively. The overall need for band removal or conversion to GBP in our series will ultimately exceed 50%.

DISCUSSION

The surgical treatment of morbid obesity has proven to be much more complex than the first bariatric surgery pioneers would have envisioned. Achieving and sustaining major reductions in body weight in the morbidly obese have been accomplished by malabsorptive surgical procedures (most notably the jejunoileal bypass procedure), but with a consequence of significant nutritional long-term risks. Gastric restrictive procedures, such as vertical banded gastroplasty and other forms of gastric stapling or banding, have weighed in at the opposite end of the surgical spectrum. These restrictive procedures, although they significantly decrease the risks of long-term nutritional complications, are not as reliable for reduction or maintenance of weight loss. One explanation is that restrictive procedures do not prevent patients from consuming a high-calorie diet in the form of concentrated sweets. 18, 19 Many bariatric surgeons currently screen sweet eaters before surgery and reject them as candidates for these types of procedures. However, it is also clear that some patients develop maladaptive eating behaviors after surgery, which can contribute to ultimate failure.

The LASGB is undergoing therapeutic trials in the United States under FDA supervision. The LASGB device involves modifications on the traditional concepts of gastric banding that were of great potential benefit. Insertion of a percutaneous needle into the subcutaneous access port offered the potential for adjustment of the band stomal diameter such that both persistent postoperative vomiting and failed weight loss might be addressed by nonsurgical means. In addition, when the LASGB trial began in the United States, minimally invasive procedures for the surgical treatment of obesity were a new and exciting concept. Wound-related complications in the morbidly obese, including major wound infections, fascial dehiscence, and incisional hernia, continue to plague the open surgical management of this disease. Thus, the opportunity to perform laparoscopic treatment offered the promise of easily quantifiable benefits to the patient.

An FDA Advisory Panel met on June 19, 2000, to consider the manufacturer’s request for early premarket approval of the LASGB device. The manufacturer was seeking more widespread release of the device for clinical use on the basis that international data as well as results of the A Trial confirmed the safety and efficacy of the device. The FDA Advisory Panel voted 6 to 4 to recommend that additional patients accrue 3 years of follow-up before approval of the device is reconsidered.

Weight loss in our series was poor. The average percentage of excess weight lost during 3 years in patients with intact bands was only 38%, despite the fact that several patients were deleted from the follow-up pool because of conversion to GBP or band removal. There was no apparent correlation between stomal diameter and weight loss. Studies from other countries report better results. 8,9,17 For example, a study by Lise et al 21 of 111 patients showed a reduction in BMI from 46.4 to 33.1 kg/m2 at 2 years of follow-up.

Safe and equally effective methods of gastric bypass for surgical weight loss would be desirable. The results of our study question the efficacy of LASGB as such a method. Reported complications included pouch dilatation, band erosion, and band slippage. 10–16 Esophageal dysmotility and dilation have been unreported until now. Esophageal dilatation developed in more than 70% of patients with an average of 2 years of follow-up in our series. Intuitively, one might expect an inverse correlation between stomal diameter and esophageal dilation, but none was found. In most of our patients, new or more severe esophageal symptoms developed after placement of the LASGB. Other studies support an increase in reflux after gastric banding. 11 Overbo et al 11 found in a study of 17 patients with the Swedish LASGB device that acid regurgitation and heartburn increased from approximately 15% to 60% after gastric banding. Other authors have reported complications such as food intolerance unresponsive to band deflation, attributable to pouch dilatation or stomal stenosis. 10–16 Kuzmak et al, 13–15 although they used a previous version of the current band system, showed that early postoperative contrast x-rays showed a pouch dilation rate of 6.5%, which increased to 50% during 4 years of follow-up. Doherty et al 22 found that 38% of patients with an adjustable silicone gastric band required hospital admission for postprandial nausea, vomiting, and severe reflux. Radiographically, these patients had enlarged proximal pouches, with delayed or absent pouch emptying and severe reflux. It is unclear whether esophageal dysmotility or dilation occurred concurrently with pouch dilation in any of these studies, because these variables were not reported. Perhaps more proximal placement of the band immediately below the gastroesophageal junction causes esophageal dilation, whereas more distal placement on the proximal stomach causes pouch dilation followed by esophageal dilation over time.

Eight patients with varying degrees of dilatation of the esophagus underwent further band tightening adjustment as a result of inadequate weight loss. Experienced international surgeons at the A Trial investigators meeting in March 1998 recommended adjusting the bands at regular intervals after surgery until the patient begins a steady weight loss. Esophageal dilatation had not been reported previously by surgeons at international sites, because contrast studies were not routinely performed. The severity of esophageal dilatation in our series may have been amplified by our adjustment strategy in half of the patients in whom this complication developed. In patients with worsening esophageal dilatation and inadequate weight loss, we believed that conversion to proximal GBP bypass was indicated. Other patients with dilatation are being followed up by interval contrast radiography to assess for regression or possible progression of the esophageal dilatation because they do not desire surgery or believe their weight loss is adequate.

We found no standard methods in the literature for measuring esophageal dilation by contrast esophagography. A radiologist’s interpretations can be viewed as subjective. We standardized our measurements by using the vertebral body height and band diameter to provide internal controls for variable film magnification. 20 The literature does, however, suggest that a normal resting esophageal diameter is less than 16 mm by gated magnetic resonance imaging studies. 23

The long-term risks of esophageal dilatation are unknown but could include achalasia-like symptoms, esophageal pulsion diverticula, or progressive development of a sigmoid esophagus that may not respond to band decompression. Appropriate management of this problem is not clear. Long-term follow-up will be required. We believe that all patients should undergo routine contrast studies at 3 years after LASGB insertion. Management of the progressively dilating esophagus should include deflation of the LASGB device, despite the fact that weight regain is likely. Failure of the esophageal contour to return to normal should probably be treated by LASGB removal. We have found that most of our patients have significant concerns about the possible long-term health effects of esophageal dilatation, despite the lack of data on this topic. We advise such patients to undergo conversion to proximal GBP.

At the FDA Advisory Panel session, 24 only 115 patients had been followed up for 3 years after the procedure. Patients lost approximately one third of excess weight, and one third of patients required either revision or explantation of the device. In a series of international patients from Europe and Australia, surgical revision or repair of tubing or removal of the device has been necessary in 28%, the most common problem being prolapse. The mean %EWL was 38%. Of these patients, only 40% with diabetes and 55% with sleep apnea showed resolution, and 22% of hypertensive patients had normal blood pressure without medication. 24 In the Swedish Obese Subjects study, 25 most patients had either vertical banded gastroplasty or implantation of the so-called Swedish band (which differs from the current device in design, introduction method, and reported results) and had only 23% loss of body weight despite a low average preoperative BMI of 42 kg/m2. The authors also noted a disappointing 47% reduction in diabetes and 42% reduction in hypertension. Not surprisingly, their data show that the risk of retaining comorbid conditions of dyspnea, chest pain, and physical inactivity, which persisted in 19%, 4%, and 17% of postoperative patients, respectively, decreased progressively with the degree of weight loss.

In terms of absolute weight loss, GBP has proven to be the gold standard by which other surgical procedures are compared. The results of the above studies must be compared with the average loss of one third of body weight (or two thirds of excess weight) after GBP, even in those with a significantly greater baseline BMI. 18,19 The correction of hypertension is between two thirds and three quarters of patients and 85% to 95% for type II diabetes in the GBP series. 26–29 Further, life-threatening comorbid conditions including sleep apnea syndrome and obesity–hypoventilation syndrome resolve and the quality of life improves in nearly all patients after proximal GBP at this degree of weight loss. In contrast, the overall weight reduction with the LASGB device is significantly less. A procedure in which patients on average lose much less than half of their excess weight will not produce the dramatic resolution of comorbidities seen with GBP. Thus, significant comorbidity such as diabetes and hypertension might be viewed as a relative contraindication to LASGB. An alternative viewpoint would suggest that improvement in comorbidities in less than half of the patients undergoing this procedure is superior to no improvement in comorbidities in patients who would decline any other type of surgical intervention, such as proximal GBP.

A decreasing risk of band slippage over time has been suggested as surgical techniques have been modified, 9,12 and it seems that posterior suture fixation of the LASGB device, in addition to the anterior sutures that are commonly placed, or placement of the device above the lesser sac, 17 should significantly decrease the risk of band slippage and the need for revisional surgery.

Our results show that the LASGB procedure is not an efficacious procedure for treatment of morbid obesity in our population of American patients. It is unclear why these results differ from those seen in other countries. African American patients were found to have significantly less weight loss than white patients; a similar racial difference in weight loss after GBP has been previously reported. 19 Thus, cultural, dietary, genetic, and metabolic factors might be implicated in the dramatic difference between weight loss in this American series compared with studies around the world. Alternatively, rigorous follow-up issues, compliance issues, or even dissatisfaction of American patients with the lesser degree of weight loss achieved with LASGB might also explain the high rate of band removal and conversion to GBP.

Highly successful weight loss procedures are already widely available for treatment of morbid obesity, including the growing option of minimally invasive techniques for performing GBP. We believe the LASGB procedure must show satisfactory long-term outcomes, particularly in terms of eliminating comorbid conditions, before the device is endorsed by the FDA as safe and effective for treatment of the estimated 10 million-plus morbidly obese Americans who qualify for surgical treatment. Further, data 10,22,24,25,30 strongly question its use in patients with preoperative gastroesophageal reflux, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or addiction to sweets, and, in the current study, in African Americans. More study is required to determine the long-term efficacy of the LASGB procedure in American patients.

Discussion

DR. JOHN J. GLEYSTEEN (Birmingham, Alabama): I rise not as a laparoscopic surgeon but as a bariatric surgeon to comment on a laparoscopic procedure that has a 40% failure leading to surgical device removal but also a simultaneous surgical way out. This doesn’t sound like the way to go. Yet, I would imagine that a conversion to an operation such as the gastric bypass would not be difficult. Is this true? Or is it also a difficult conversion?

I’m about to start participation in another trial in the United States of gastric pacing to reduce weight. This is a matter of implanting bipolar electrodes on the stomach wall, and it is minimally invasive. And there is background data to suggest that it has some potential worth. It can be dismantled, and it can be converted if it does not work, but some patients will probably find it just fine. Shouldn’t it or other less invasive trials be tried? None of them are going to match the standard of the gastric bypass.

And, lastly, an issue that I think is probably of more concern: there are lots of laparoscopic surgeons and they are looking for applications. They are already moving rapidly into bariatric surgery with the bypass procedure. This laparoscopic band is not, as I would presume, particularly difficult. And if it were to become available in the United States, will then more surgeons jump into the field to do the “easy procedure,” however exactly or properly, and leave the patient afterward to fend for his own with his primary doctor? I should think this is wrong. Is this really a worry?

I thank the authors and the Association for the opportunity to discuss this provocative paper.

Dr. WARD O. GRIFFEN (Frankfurt, Mississippi): Dr. Baker, Dr. Townsend. Before I make my comments, I’d like to congratulate President Aust for being here for the entire afternoon. I think it shows his stamina, number one, and his persistence. And then I remembered, he is actually doing a job for the Southern Surgical, so he sort of has to be here; otherwise, he might be out with his family, all of whom are here, I understand. Dr. Sugerman asked me if I would comment on this paper and provided me with a manuscript – all yesterday. I am happy to make some remarks.

First, I think it would be good to get into the literature a paper about the inadequacy of gastric banding as a method of providing long-term relief of morbid obesity, particularly to counteract some of the optimistic reports that have come from overseas. In this group of patients, only 4 of the original 36 patients have achieved a satisfactory weight reduction, and that barely – although there are two that Dr. Sugerman tells me are doing quite well. There is abundant evidence that gastric banding, done as an open procedure, is not a particularly good operation, and I don’t know why the Nintendo approach should be expected to fare any better, even with improvements in the design of the band. Now we have an additional postoperative complication and that is this business of esophageal dilatation, which I don’t think has been reported very much by the overseas authors. I wonder if we aren’t going to see some very difficult problems from that, as Dr. Sugerman indicated.

The fundamental flaw in gastric banding, just as with vertical banded gastroplasty, is that the food stream goes into the distal stomach and, hence, a normal pathway. Eventually, the majority of the patients will outeat the operation – sweets or no sweets, as far as I’m concerned. On the other hand, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has three obstacles to overeating: small pouch size, very small stoma, and food entering the jejunum from the pouch. In many cases, the latter leads to unpleasant postprandial discomfort that encourages the persons to eat food, more akin to the diet that they could have used to lose weight without an operation.

I have several questions.

I hope neither you nor the patients are being charged for the device, since this is an FDA-sponsored program. Is that true?

What are the continuing results with laparoscopic gastric bypass? I know that you are doing them, and I wonder if you would enlighten us as to how that is going, because that does seem to be a simpler approach to gastric bypass than the open procedure, and it certainly seemed to be the rage at the recent clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Finally, what are you and other bariatric surgeons doing in the search for a nonoperative approach to morbid obesity? I think everybody interested in this problem, and particularly bariatric surgeons, ought to be involved in trying to determine some kind of nonoperative approach.

I enjoyed the presentation.

DR. MARK A. TALAMINI (Baltimore, Maryland): Dr. Baker, Dr. Townsend. I rise as the inverse of Dr. Gleysteen, a laparoscopic surgeon who is not an obesity surgeon. And I congratulate Dr. Sugerman and colleagues on an important and detailed analysis of the use of the laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding device. As leaders in the arena of obesity surgery, it is certainly appropriate for their group to investigate such an important potential development in the field of laparoscopic obesity surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery has created a necessary and sometimes uncomfortable partnership between industry and surgeons: we can’t do the surgery without their tools, and they can’t make their stockholders happy without us using their product. This partnership usually works out well when it actually advances patient care. But this paper suggests that with this device, the opposite may well be true. I would like to ask the authors a few devil’s advocate questions.

This device is less surgery than traditional approaches. And as your study points out, it appears to be less efficacious. But why not offer half a loaf to some of these patients that might bring more folks to the operating room for at least some relief?

This is one element, I know, of a multicenter trial, and there have been a number of international studies. I wonder if you would be willing to comment on differences in weight reduction rates, removals, and complications between your study and those studies, as I believe there are some differences.

Why do the failures occur late with this device after the first 2 years?

Finally, I would like to hear your thoughts regarding this type of device in general. Do you think there will ever be a successful device like this that could be easily placed laparoscopically, or is this approach doomed to failure? And if there is such a device, what might its characteristics be?

I thank the Society for the privilege of the floor.

DR. BRUCE D. SCHIRMER (Charlottesville, Virginia): Dr. Baker, Dr. Townsend, members, and guests. I wish to first congratulate Dr. Sugerman, Dr. DeMaria, and their colleagues on a very excellent presentation, and I wish to preface my comments by saying I am not a bona fide expert on this operation, having never done it on a human, nor am I an advocate of it.

We need to pay close attention to these findings that were presented to us here today by our colleagues at MCV, since in a sense they are a disinterested party in assessing this operation, having one of the world’s largest and most successful experiences in gastric bypass to treat severe obesity. The lap-band is not the only arrow in their quiver when it comes to surgical treatment of obesity, which leads to my first question.

Dr. Sugerman, as you have said, there are many centers in Europe where hundreds of patients have had the lap-band placed for at least 6 years or longer. They have not issued any reports in the literature on esophageal dilatation. Do you and your colleagues truly believe that this does not exist in their series, or do you have any insight from communication or otherwise that in fact it may well exist but it just has not been published heretofore?

My second question concerns the tradeoff – and again, this is a devil’s advocate question – the tradeoff between weight loss and mortality. The lap-band clearly in published series is associated with a lower mortality than gastric bypass. If hypothetically we in the United States could reproduce the same single-digit reoperative and complication rates that have been published by our colleagues in Europe and Australia with the lap-band, what in your opinion would be the acceptable percentage of excess weight loss which would need to be achieved by this procedure in order for us to consider using it in our patients, given that the mortality rate for lap-band is probably about five to ten times less than that of gastric bypass?

I wish to thank the Association for the privilege of the floor.

DR. BRUCE MACFADYEN (Houston, Texas): I want to thank Dr. Sugerman for his wonderful presentation of his early results with the use of the gastric band. I am fascinated by the fact that he did observe esophageal dilatation. From what I have read in the European literature, of which they have done several thousand of these things, their early experience was that of band slippage. And I know that this has been – at least they report anyway – that this has been modified so that it is not an occurrence at the present time, or at least a low incidence of it. And so in regards to the esophageal dilatation, my question is, was there any evidence of band slippage? And if there was band slippage, up over and into the esophagus, was there any inflation or greater inflation of the balloon in order to produce some degree of weight loss?

Because there have certainly been reports in the literature of using a Dacron band around the upper part of the stomach. And although that certainly had complications, it produced a steady-state outlet from the upper to the lower pouch. And whether this adjustable band was adjusted a great deal because sometimes the patients wanted it adjusted, you might explain when they were adjusted and when they were not, and if there were times when there was no inflation of the balloon at all.

I think that is an issue and can be very problematic in evaluating some of the results. But I appreciate their concerns, and I think that the potential of greater than 50% removal of these bands, I think, is very significant and should cause a great deal of concern for potential use in the future.

I want to thank the Society for the opportunity to discuss this paper.

DR. ERIC J. DEMARIA (Richmond, Virginia): I’d like to thank all the discussants for their comments and their questions. And given the large number, I will do my best to keep them straight.

There was in fact no charge for the banding device to our patients; however, the operative procedure was charged and the hospital bill for this operation was in the range of $18,000 at our institution.

Questions were asked about the conversion of laparoscopic banding to gastric bypass and the obvious observation that you would imagine it to be a fairly easy conversion, and in our experience that was untrue. We have converted 11 patients to gastric bypass. We have converted half a dozen patients laparoscopically to gastric bypass at this time; however, these procedures are not easy and we have had several patients with intraoperative leaks requiring repeated suture repair and gastrostomy tubes. We have had patients – one patient had a takeback for bleeding from the liver capsule, and we had one postoperative abscess related to a leak that, fortunately, resolved with percutaneous drainage. So it is not an easy conversion operation. There’s a fair amount of adhesions in the area of the band to the liver capsule and to the surrounding stomach.

In terms of elaborating on the problem of esophageal dilatation, we do not know the natural history of this phenomenon. It is a fact that during our recognition process, we inflated some bands about eight times in patients who had some degree of esophageal dilatation on contrast study until we realized the magnitude of the problem. We were in pursuit of weight loss, which you have heard from our data was an elusive end point in this population.

We were instructed by European investigators, who all admit to having seen this complication on an occasional basis but not a regular basis, to inflate the bands in pursuit of weight loss is the only outcome parameter that was important. And it was very frustrating to take care of patients who had a dilated esophagus and had not lost very much weight and wanted to lose more.

And in particular, several discussants commented on the outcome that we should be following. One of the ones that is most important in this population is resolution of comorbidity. In our population we had eight diabetics. Only two of our diabetics resolved their diabetes following the lap-band procedure, and only 50% of our hypertensives resolved their hypertension during the weight loss period. So if you look at that as an end point that is objective and meaningful, I think that the band falls short.

It is an interesting question to ask what is a surgical procedure that might be less invasive and less risky than gastric bypass and what weight loss would be acceptable for that procedure. I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t think we have found the answer with the lap-band procedure, the problem being that if the patients have to undergo revisional surgeries and so forth, to the tune of at least 50%, I don’t think we can qualify that as an effective procedure for obesity treatment. However, there are promising things on the horizon such as gastric pacing, which is a very interesting area for future investigation.

And, finally, a comment on the large number of laparoscopic surgeons who are now becoming interested in obesity surgery. There is a huge issue in the United States related to the number of patients needing surgical treatment, which is the only proven efficacious treatment for obesity, compared to the number of surgeons available to perform those operations. The ASBS membership compared with the overall population of patients who need surgery is about 33,000 patients per surgeon member of that society. So, obviously, you could make your career out of offering obesity surgery and have plenty left over for the others. The question is whether bariatric surgery as a field that has had a difficult evolutionary process can tolerate the widespread use of an operation that is not effective in most patients. The treatment protocols for these patients are labor-intensive. They require a great deal of effort on the part of the surgeon and the dietitian in frequently evaluating, adjusting, and readjusting the patients. It is not an easy population to follow. And we are very concerned that it will give bariatric surgery a bad name in the future to add this procedure to the U.S. repertoire.

I would like to point out that in the U.S. study overall, there is a one-third removal or revision rate, so our data are not unusual in that regard. And in the international data set presented at the FDA hearing, they noted a 28% risk of revision.

I hope that I have covered most of the questions. I thank the Society for the privilege of presenting our data.

Footnotes

Presented at the 112th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 4–6, 2000, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Eric J. DeMaria, MD, Medical College of Virginia of Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Surgery, P.O. Box 980519, Richmond, VA 23298.

E-mail: edemaria@hsc.vcu.edu

Accepted for publication December 2000.

References

- 1.Greenstein RJ, Rabner G, Taler Y. Bariatric surgery vs. conventional dieting in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg 1994; 4: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. Int J Obesity 1992; 16: 397–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellum JM, DeMaria EJ, Sugerman HJ. The surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Curr Probl Surg 1998; 35: 796–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colditz GA. Economic costs of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1992; 55: S503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Statement. Am J Clin Nutr 1992; 55:615S–619S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mason EE, Tang S, Renquist KE, et al. A decade of change in obesity surgery. Obes Surg 1997; 7: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuzmak LI. Stoma adjustable silicone gastric banding. Probl Gen Surg 1992; 9: 298–317. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadiere GB, Himpens J, Vertruyen M, et al. Laparoscopic gastroplasty (adjustable silicone gastric banding). Semin Laparosc Surg 2000; 7: 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien PE, Brown WA, Smith A, et al. Prospective study of a laparoscopically placed, adjustable gastric band in the treatment of morbid obesity. Br J Surg 1999; 86: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Wit LT, Mathus-Vliegen L, Hey C, et al. Open versus laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overbo KK, Hatlebakk JG, Viste A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in morbidly obese patients treated with gastric banding or vertical banded gastroplasty. Ann Surg 1999; 228: 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favretti F, Cadiere GB, Segato G, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding (Lap-Band®): how to avoid complications. Obes Surg 1997; 7: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuzmak LI, Rickert RR. Pathologic changes in the stomach at the site of silicone gastric banding. Obes Surg 1991; 1: 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuzmak LI, Burak E. Pouch enlargement: myth or reality? Impressions from serial upper gastrointestinal series in silicone gastric banding patients. Obes Surg 1993; 3: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzmak LI. A review of seven years’ experience with silicone gastric banding. Obes Surg 1991; 1: 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelala E, Cadiere GB, Favretti F, et al. Conversions and complication in 185 laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding cases. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 268–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belachew M, Legrand M, Vincent V, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. World J Surg 1998; 22: 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugerman HJ, Starkey JV, Birkenhauer R. A randomized prospective trial of gastric bypass versus vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity and their effects on sweets versus non-sweets eaters. Ann Surg 1987; 205: 613–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugerman HJ, Londrey GL, Kellum JM, et al. Weight loss after vertical banded gastroplasty and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity with selective versus random assignment. Am J Surg 1989; 157: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szucs RA, Turner MA, Kellum JM, et al. Adjustable laparoscopic gastric band for the treatment of morbid obesity: radiologic evaluation. Am J Radiol 1998; 170: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lise M, Favretti F, Belluco C, et al. Stoma adjustable gastric banding: results in 111 consecutive patients. Obes Surg 1994; 4: 274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doherty C, Maher JW, Heitshusen DS. Prospective investigation of complications, reoperations, and sustained weight loss with an adjustable gastric banding device for treatment of morbid obesity. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakashima A, Nakashima K, Seto H, et al. Normal appearance of the esophagus in sagittal section: measurement of the anteroposterior diameter with ECG gated MR imaging. Radiol Med 1996; 14: 77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Transcript of Proceedings of the Department of Health and Human Services Food & Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Gastroenterology and Urology Panel of the Medical Devices, Advisory Committee, June 19, 2000.

- 25.Karason K, Lindroos AK, Stenlof K, et al. Relief of cardiorespiratory symptoms and increased physical activity after surgically induced weight loss. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1797–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foley EF, Benotti PN, Borlase BC, et al. Impact of gastric restrictive surgery on hypertension in the morbidly obese. Am J Surg 1992; 163: 294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carson JL, Ruddy ME, Duff AE, et al. The effect of gastric bypass surgery on hypertension in morbidly obese patients. Ann Intern Med 1994; 154: 193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 1995; 222: 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pories WJ, MacDonald KG Jr, Morgan EJ, et al. Surgical treatment of obesity and its effect on diabetes: 10-year follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr 1992; 55: 582S–585S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morino M, Toppino M, Garrone C. Disappointing long-term results of laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 868–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]