Abstract

Atovaquone is an antiparasitic drug that selectively inhibits electron transport through the parasite mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex and collapses the mitochondrial membrane potential at concentrations far lower than those at which the mammalian system is affected. Because this molecule represents a new class of antimicrobial agents, we seek a deeper understanding of its mode of action. To that end, we employed site-directed mutagenesis of a bacterial cytochrome b, combined with biophysical and biochemical measurements. A large scale domain movement involving the iron-sulfur protein subunit is required for electron transfer from cytochrome b-bound ubihydroquinone to cytochrome c1 of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Here, we show that atovaquone blocks this domain movement by locking the iron-sulfur subunit in its cytochrome b-binding conformation. Based on our malaria atovaquone resistance data, a series of cytochrome b mutants was produced that were predicted to have either enhanced or reduced sensitivity to atovaquone. Mutations altering the bacterial cytochrome b at its ef loop to more closely resemble Plasmodium cytochrome b increased the sensitivity of the cytochrome bc1 complex to atovaquone, whereas a mutation within the ef loop that is associated with resistance in malaria parasites rendered it resistant to atovaquone. Interestingly, the atovaquone resistance-associated mutation led to a 10-fold reduction in the efficiency of the cytochrome bc1 complex, suggesting that it may exert a cost on efficiency of the cytochrome bc1 complex, without compromising seriously the growth of the organism.

Malaria is one of the world’s most intractable human afflictions. Despite intensive campaigns against the parasitic disease, an estimated 300 to 500 million cases still occur each year. Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of the most lethal form of malaria, is responsible for over 2 million deaths annually, largely among young children and pregnant women (1, 2). Efforts to eradicate malaria have not been successful, and the situation may be worsening due, in large part, to the emergence and spread of drug resistant parasites. The need for new antimalarial drugs is now widely recognized. Atovaquone represents a new class of drugs having a metabolic target different from extant antimalarial drugs to which resistance is widespread. Atovaquone was found to be a very effective antimalarial compound, but unsuitable for use as a single agent due to the relatively quick emergence of resistance (3–5). However, in combination with the synergistic agent proguanil, it has been effective for both therapeutic and prophylactic uses (5–7). On the other hand, once atovaquone resistance has arisen, the combination is no longer effective against malaria parasites (8, 9).

Previous studies have shown that atovaquone selectively inhibits mitochondrial electron transport in the parasite, consistent with the prevalent theory that hydroxynaphthoquinones function as ubiquinone antagonists (10, 11). Additionally, atovaquone was found to collapse the parasite mitochondrial membrane potential at nanomolar concentrations (11), and its effect on the membrane potential is enhanced by synergistic activity of proguanil (12). To derive a better molecular understanding of atovaquone’s mode of action, a series of independently derived atovaquone resistant malaria parasites were investigated (9). All of the resistant parasite clones contained mutations in a specific, well-conserved segment of the cytochrome b subunit of the cytochrome bc1 complex (ubihydroquinone-cytochrome c oxidoreductase), thus identifying a likely binding region within the ubihydroquinone oxidizing (Qo) site of the malaria bc1 complex (9). Similar mutations associated with atovaquone resistance have been identified in clinical isolates (13, 14), as well as in experimental rodent malaria models (15).

With mitochondrial electron transport having been validated as an important target for antimalarial drugs, it will be helpful to derive molecular details of atovaquone interactions with the cytochrome bc1 complex with the hope of exploring alternate compounds with antimalarial activity. Recent determinations of the structure of two examples of the vertebrate cytochrome bc1 complex (16, 17), followed by those of yeast (18) and the bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus (19), have provided significant insights into the mechanisms involved in the functioning of this enzyme. Since a large body of experimental work indicates that the active centers and core subunits of the enzyme complex are well conserved (reviewed in references (20–23)), we have begun to explore a relatively accessible bacterial system to help uncover molecular details of atovaquone’s mode of action. The potentially key region in cytochrome b associated with atovaquone resistance exhibits a particularly high degree of similarity between the malarial and bacterial complexes. In Rhodobacter capsulatus, the cytochrome bc1 complex consists of only three subunits, which are amenable to site-directed mutagenesis, and its three dimensional structure has recently been determined (19). Using this bacterial system, it has been possible to demonstrate an unprecedented large amplitude domain movement involving the [2Fe-2S] protein that accompanies electron transfer from ubihydroquinone bound within cytochrome b to cytochrome c1 (24, 25); see also (26), and references therein). In this work, we have constructed R. capsulatus cytochrome b substitution mutants predicted to have either enhanced or reduced sensitivity to atovaquone. Characterization of the altered cytochrome bc1 complexes through biochemical and biophysical approaches provides new insight into the molecular mode of action of atovaquone as a potent antimalarial drug.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth, in the presence of appropriate antibiotics, and R. capsulatus strains in mineral-peptone-yeast-extract enriched medium (27) or in RCVB medium (28) containing 5 mM glutamate, in the presence of 10 μg/ml kanamycin. Respiratory or photosynthetic growth of R. capsulatus strains was at 30–35°C in the dark under semiaerobic conditions or in anaerobiosis under continuous light, respectively. MT-RBC1 is a cytochrome bc1– strain in which the chromosomal copy of the petABC operon (also called fbcFBC) has been deleted and replaced by a gene cartridge conferring resistance to spectinomycin (27). The strain pMTS1/MT-RBC1 corresponds to MT-RBC1 complemented in trans with the plasmid pMTS1 (29), which is a broad-host-range plasmid that provides resistance to kanamycin and contains a wild-type copy of petABC.

Molecular Genetic Techniques

Mutations were constructed by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis in plasmid pPET1 (27), using either a Pfu polymerase/DpnI strategy, as described (30), or using the “Gene Editor” T4 DNA polymerase/marker co-selection system from Promega, with minor modifications of the manufacturer’s protocol. The mutagenic oligonucleotides used were (with the changes to the parental sequences denoted in bold italics): 5′-CGGCGGCAAAGGCCTTCAGCATCGCGTAG A-3′ (I304M+R306K), 5′-GTCGGCGGCAAAGGCCCGGAGGATCGCGCAGAACGGCAG-3′ (Y302C), and 5′-GTCGGCGGCAAAGGCTTTCAGCATCGCGCAGAACGGCAG-3′ (Y302C in M304/K306 background). Each oligonucleotide introduces a silent change to a restriction enzyme recognition site (underlined), as well as the target mutation(s). Sequences of the auxiliary oligonucleotides used in mutagenesis and sequencing are available on request. The SmaI-BstBI fragment of the pPET1 derivative containing the mutation thus generated was then exchanged with its wild-type counterpart in pMTS1, and the newly constructed plasmids were introduced into MT-RBC1 via triparental crosses (27). In all cases, the presence of the desired mutation and absence of any additional mutation on the insert thus exchanged was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The entire gene encoding cytochrome b was sequenced from a post-experiment sample of bacteria expressing the triple I304M+R306K+Y302C-substituted cytochrome bc1 complex.

Biochemical and Biophysical Techniques

Intracytoplasmic membrane (chromatophore) preparation, protein determination, and 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-decyl-1,4-benzohydroquinone:cytochrome c reductase assays were performed as described (27), except that protein determinations were carried out in the presence of 1% SDS without prior extraction of pigments. Representative experimental results displayed in the figures in this article were obtained using samples prepared from semiaerobically grown cells.

SDS/PAGE was performed by using an acrylamide concentration of 15% (wt/vol), and gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Proteolysis experiments with thermolysin were done basically according to Valkova-Valchanova et al. (25), using chromatophore membranes prepared in the presence of 17 mM EDTA, then extensively washed, dispersed in 1 mg dodecylmaltoside per mg of total proteins, and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 2 nmol of thermolysin, and 30 nmol stigmatellin or atovaquone, when specified, in a total reaction volume of 50 μL. Aliquots were analyzed by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against the iron sulfur protein of R. capsulatus (25).

EPR measurements were performed on a Bruker ESP-300E spectrometer (Bruker Biosciences). Temperature control was maintained by an Oxford ESR-9 continuous flow helium cryostat interfaced with an Oxford model ITC4 temperature controller. The frequency was measured with a Hewlett-Packard model 5350B frequency counter. Unless otherwise noted, the operating parameters were as follows: sample temperature, 20K; microwave frequency, 9.45 GHz; microwave power, 2 mW; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 20.243 G; and time constant, 163.84 ms. Samples were poised with the ubiquinone pool oxidized and [2Fe-2S] cluster reduced by addition of 20 mM sodium ascorbate.

Light-induced, single-turnover, time-resolved kinetics were performed as described (24, 31) by using chromatophore membranes and a single wavelength spectrophotometer (Biomedical Instrumentation Group, University of Pennsylvania) in the presence of 2.5 μM valinomycin, N-ethyl-dibenzopyrazine ethyl sulfate, N-methyl-dibenzopyrazine methyl sulfate, 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, and 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. Transient cytochrome c re-reduction kinetics initiated by a short saturating flash (8 μs) from a xenon lamp was followed at 550-540 nm. The concentrations of antimycin A, atovaquone, myxothiazol, and stigmatellin used were 5, 10, 5, and 1 μM, respectively, and the ambient potential was poised at 100 mV.

RESULTS

Properties of R. capsulatus with mutated cytochrome b.

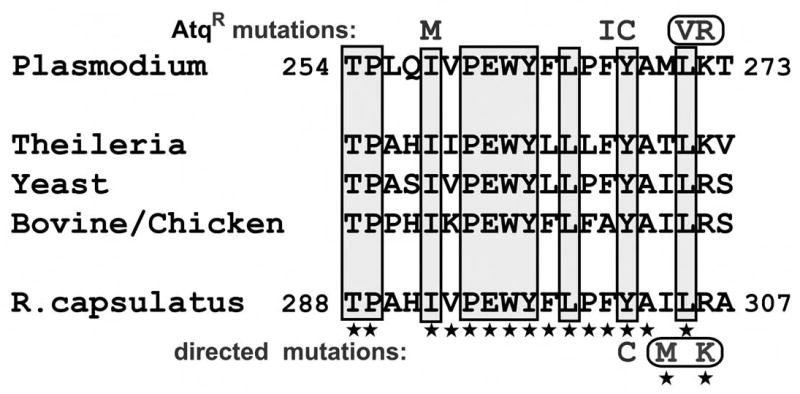

While a functional cytochrome bc1 complex is not required for aerobic growth of R. capsulatus due to the presence of an alternate respiratory pathway (32), this enzyme is essential for its anoxygenic photosynthetic growth. Thus, in bacteria with a mutated cytochrome bc1 complex, under appropriate conditions, photosynthetic growth rate reflects the functional efficiency of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Comparing the cytochrome b sequence of Plasmodium and R. capsulatus around a highly conserved portion of the Qo site (part of the ef loop, containing the conserved “PEWY” motif (Fig. 1)), which is believed to be involved in the binding of atovaquone (9), we noticed remarkable identity between these organisms – within the segment from residue 292 to 306 (bacterial numbering) all the amino acids are identical except two, and these two represent conservative changes (Fig 1). Since atovaquone binding affinity is likely influenced by subtle local changes, we mutated the two R. capsulatus residues (I304 and R306) to their respective Plasmodium counterparts (M and K) to better mimic the structure of the malaria cytochrome bc1 complex in this region. We also mutated Y302 to cysteine (C302) in both the wild type and the M304/K306 backgrounds. This tyrosine corresponds to the site most frequently found altered in clinical cases of malaria atovaquone resistance (8, 14). These R. capsulatus mutant strains were examined for their anaerobic photosynthetic growth rate as well as for the specific activity of their cytochrome bc1 complex in isolated chromatophore membranes. As shown in Table 1, the photosynthetic growth rate was reduced by 20–25% of the wild type rate in M304/K306 and C302 strains, but was reduced by 50% in the strain bearing all three amino acid substitutions. We isolated chromatophore membranes from these strains to assess their cytochrome bc1 complex activity. The overall protein content, as well the b- and c-type cytochrome content of these membrane preparations were similar (Table 1), indicating that all strains produced and assembled comparable amounts of cytochrome bc1 complexes under the conditions used. The cytochrome bc1 complex activity was reduced only modestly in the M304/K306 strain, but by about 90% in strains bearing the atovaquone resistance-associated C302 substitution. These observations were consistent with the greater effect of the latter substitution on photosynthetic growth of R. capsulatus, although the degree of growth retardation was lower than its effect on enzymatic function, presumably due to the overexpression of the cytochrome bc1 complex in a trans-complemented “wild type” strain.

Fig. 1.

Aligned amino acid sequences from the ef loop of cytochromes b from P. yoelii, R. capsulatus, and other selected species. (Amino acid residues 254–273 in P. yoelii cytochrome b / 288-307 in R. capsulatus) The shaded boxes enclose positions that are largely conserved among the known cytochrome b sequences. Characters above the P. yoelii sequence show the substitutions that were found in atovaquone resistant P. yoelii isolates; a rounded box surrounds the V and R substitutions indicating that they occurred together in the same resistant isolate. Stars below many of the amino acid residues of the R. capsulatus cytochrome b mark those that are identical to the corresponding residues in P. yoelii cytochrome b. Characters below the R. capsulatus sequence denote the substitutions in the bacterial cytochrome b engineered for this study. The M and K substitutions are surrounded by a box to indicate that they were engineered to occur jointly in the same cytochrome b gene product.

TABLE I.

Relevant properties of R. capsulatus cells and chromatophore membrane preparations

| Strain (batchesa) | Description [plasmid]/host strain | Relative PSbgrowth rate | Protein content of mbc mg/mle | cytdbcontent of mbc nmol/mge | cytdc+c1content of mbc nmol/mge | Relative cytdcreductase activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (5) [Y302/I304/R306] | [pMTS1]/MT-RBC1 | 100%f | 23+/−6 | 3.1+/−0.3 | 1.8+/−0.2 | 100%g |

| M304/K306 (4) | [pMTS:I304M+R306K]/MT-RBC1 | 87% | 19+/3 | 2.8+/−0.4 | 1.6+/−0.3 | 80% |

| C302 (3) | [pMTS:Y302C]/MT-RBC1 | 75% | 20+/−3 | 2.8+/−0.1 | 1.8+/−0.2 | 11% |

| M304/K306/C302 (5) | [pMTS:I304M+R306K+Y302C]/MT-RBC1 | 47% | 23+/−3 | 2.9+/−0.3 | 1.8+/−0.3 | 9.1% |

number of membrane preparations assayed (for measurements other than the PS growth rate).

PS=photosynthetic

mb=membrane

cyt=cytochrome

The data presented are mean values ± SD (standard deviation).

growth rate of 100% = 0.225 h−1 exponential growth coefficient.

100% relative activity = 5.81+/− 0.42 μmol cytochrome c reduced/min/mg protein.

Inhibition of the cytochrome bc1 complex by atovaquone and other Qo site inhibitors.

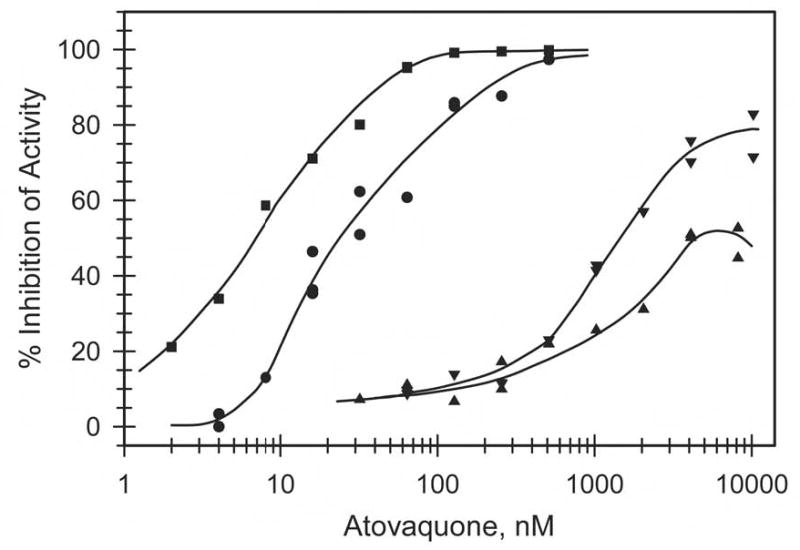

We assessed inhibition profiles of atovaquone, stigmatellin and myxothiazol on cytochrome bc1 complex activity in chromatophores membranes prepared from the R. capsulatus strains described above. Representative inhibition plots from the atovaquone titrations are shown in Fig. 2, and the average measured mid-point inhibition concentrations (IC50) for the three inhibitors for each strain are given in Table 2. The wild type cytochrome bc1 complex was inhibited by atovaquone with IC50 of about 30 nM. However, unlike stigmatellin or myxothiazol (33), R. capsulatus growth is not inhibited by atovaquone when the drug is included in the medium, possibly due to lack of accessibility to its site of action in intact bacteria. Cytochrome bc1 complex from the strain bearing the M304/R306 substitutions was inhibited by atovaquone with IC50 of about 10 nM. This 3-fold reduction in IC50 is consistent with our prediction that subtle changes observed in the Plasmodium cytochrome b are responsible for the enhanced therapeutic window for atovaquone. The substitution corresponding to one commonly seen in atovaquone resistant human malaria parasites, C302, dramatically increased the IC50 of atovaquone in the cytochrome bc1 complex. This was observed in both the wild type and M304/R306 background strains. These results now formally confirm a causal relationship between the alteration of a conserved tyrosine residue within the ef loop and acquisition of atovaquone resistance in malaria parasites. It was interesting to note that C302 substitution had much more modest effects on IC50 for two other Qo site inhibitors, stigmatellin and myxothiazol, increasing it by 2–20 fold compared to 100–200 fold for atovaquone (Table 2). These results are consistent with the crystallographically defined binding niches of the former two inhibitors at the Qo site (34), and with the structural differences among the Qo site inhibitors, in particular, the inflexible cyclohexyl-chlorophenyl moiety of atovaquone, highlighting the divergence between the specific sub-sites occupied by these Qo site inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase activity of wild type and mutated bc1 complexes. The activity present in chromatophore membranes was measured as described in the Experimental Procedures in the absence and presence of various concentrations of atovaquone. Per cent inhibition was calculated using the activity in the absence of atovaquone as 0% inhibition. Circles, preparation containing wild type bc1 complex; squares, with M304/K306-containing complex; triangles, with C302-containing complex; inverted triangles, with M304/K306/C302-containing complex.

TABLE II.

Effect of Qo site Inhibitors: IC50 value from titrations of activity

| Strain (batchesa) | Atovaquone IC50, nMb | Stigmatellin IC50, nMb | Myxothiazol IC50, nMb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (5) | 27.5+/−7.8 | 5.7+/−1.0 | 7.5+/−0.9 |

| M304/K306 (4) | 9.6+/−3.6 | 6.4+/−0.8 | 14+/−1.4 |

| C302 (3) | ~2500c | 10+/−0.1 | 95+/−7 |

| M304/K306/C302 (5) | ~1800c | 23+/−6 | 320+/−49 |

number of membrane preparations titrated.

The data presented are mean values ± SD (standard deviation).

approximate average value based on extrapolation of the early portions of the inhibition vs concentration curves. In the case of the mutations that produce resistance to atovaquone, the curves for atovaquone level off well before reaching 100% inhibition (cf Fig. 2) and the apparent inhibition decreases at higher concentrations of inhibitor. This appears to be due to the poor solubility of atovaquone in aqueous buffers, and since the time to the onset of precipitation varies, inconsistent assay results are obtained at the higher concentrations.

Effect of Inhibitors on the Ubihydroquinone Oxidation Site (Qo)-Iron-Sulfur Cluster ([2Fe-2S]) Interaction Probed by EPR Spectroscopy

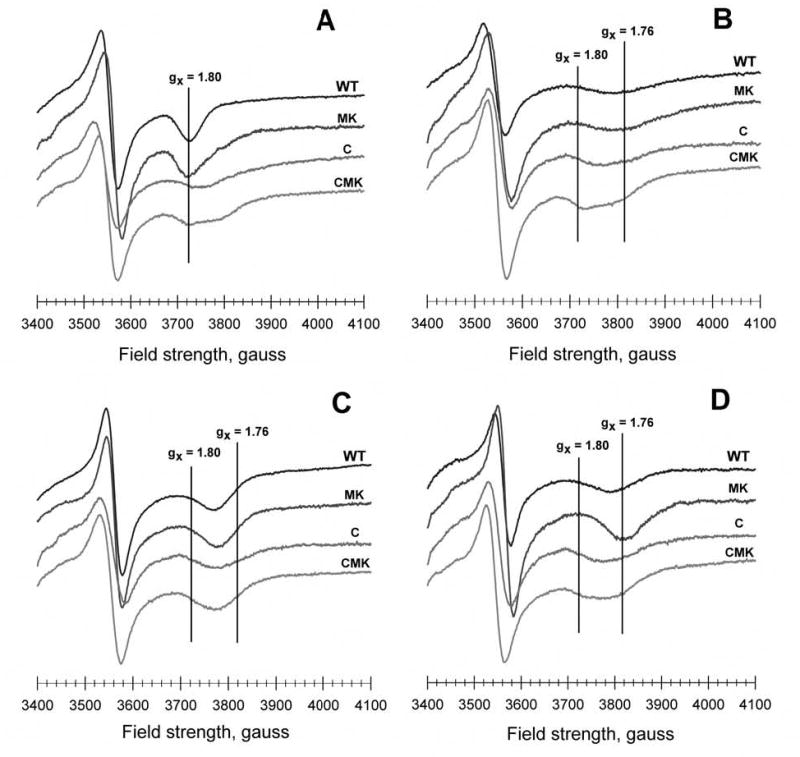

The EPR spectrum of the [2Fe-2S] cluster is very sensitive to its molecular environment, and therefore, to local conditions surrounding it, including the conditions at the Qo site in cytochrome b (35). In the native enzyme, this spectrum exhibits a relatively sharp gx transition at a g~1.80 value, which is indicative of the interactions of the reduced [2Fe2S] cluster with ubiquinone in the Qo site (Fig. 3A) (36). Thus, to assess the effects of Y302 and M304/K306 mutations on these interactions, the EPR spectra of appropriate wild type and mutated enzyme complexes in chromatophores were examined in the absence and presence of inhibitors. The gx signal of the cytochrome bc1 complex carrying the M304/K306 substitutions is slightly shifted to lower magnetic field and broader than that of the wild type enzyme (Fig 3A), which could be due to subtle differences in the interactions of the [2Fe-2S] cluster with the Qo site in the mutant enzyme. In the presence of myxothiazol, stigmatellin or atovaquone this gx signal shifts to higher magnetic field and broadens to various extents depending on the inhibitor added (Fig 3B, C or D, respectively). These spectra are similar to previously reported spectra in the case of myxothiazol and stigmatellin (35,36), indicating that the Qo site of the cytochrome bc1 complex carrying the M304/K306 mutations is not drastically perturbed in comparison to the wild type enzyme. Interestingly, in the case of atovaquone and the M304/K306 cytochrome bc1 complex, the gx signal is sharper and shifted farther (to ~1.76) than that seen with the wild type enzyme, suggesting that in this mutant the [2Fe-2S] cluster-atovaquone interactions are more pronounced.

Fig. 3.

EPR signals of the iron-sulfur cluster in wild type and mutated bacterial bc1 complexes within chromatophore membrane preparations in the absence and presence of inhibitors. The iron-sulfur cluster of each sample was reduced with ascorbate, and low temperature EPR spectra were recorded under the conditions described in the Experimental Procedures. The y-axis of the samples in each panel is offset to facilitate visualization: (A) untreated samples, (B) treated with 300 μM myxothiazol, (C) treated with 100 μM stigmatellin, and (D) treated with 100 μM atovaquone.

When the EPR spectra of the cytochrome bc1 complexes carrying the single C302 and the triple C302/M304/K306 mutations were compared with that of the wild type enzyme significant differences were observed (Fig. 3). The gx transition broadened and shifted from 1.80 to 1.79, reflecting altered interactions between the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the Qo site and its occupants. In the presence of myxothiazol or stigmatellin, the two cytochrome bc1 complexes carrying the C302 mutation also exhibited a broad gx signal, at about the same position as those observed with atovaquone. Moreover, in this region of the spectra multiple overlapping transitions are visible in the absence of inhibitor or in the presence of myxothiazol (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting some sample heterogeneity. Interestingly, in the presence of atovaquone, both of the cytochrome bc1 complexes carrying the C302 mutation exhibited a broad gx transition at a g value of 1.78, closer to that seen with the wild type, rather than the sharper g=1.76 signal of the M304/K306 enzyme. Thus, the data clearly revealed that atovaquone has a unique and possibly stronger interaction with the [2Fe-2S] cluster of the cytochrome bc1 complex carrying the M304/K306 substitutions, which is disrupted by the Y302C mutation.

Single turnover kinetics of the cytochrome bc1 complex in presence of various inhibitors

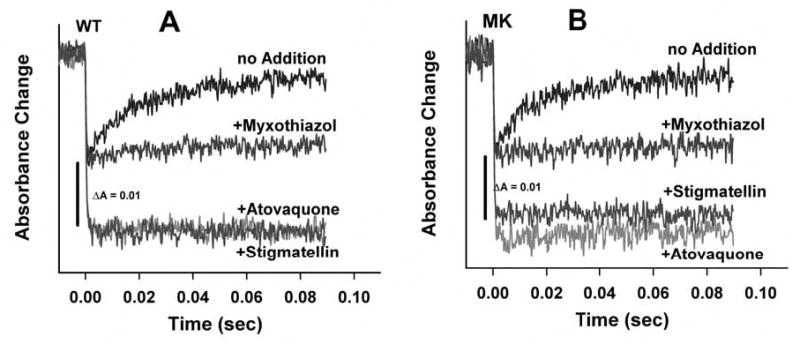

Chromatophores containing cytochrome bc1 complexes were also studied in light-initiated rapid kinetic experiments, which monitor the transfer of electrons to cytochrome c during a single turnover of the enzyme. In these experiments, the cytochrome c re-reduction kinetics are initiated by an actinic flash that excites photosynthetic reaction centers in the chromatophores, which in turn, rapidly oxidize cytochrome c molecules, which are then re-reduced by the cytochrome bc1 complexes. The kinetics of wild type and M304/K306 mutant were virtually identical, with an initial rapid phase (due to electron transfer from the pre-reduced [2Fe-2S] cluster, completed in the dead time of the instrument (24) and only revealed in the presence of stigmatellin ) and a slower phase involving re-reduction of the [2Fe-2S] cluster by ubihydroquinone in the Qo site and subsequent reduction of additional cytochrome c by the reduced cluster (Fig. 4). The single turnover kinetics exhibited by the wild type and the M304/K306-substituted cytochrome bc1 complexes also responded identically to the presence of excess Qo site inhibitors. Myxothiazol blocks the slow phase of cytochrome c reduction by eliminating ubihydroquinone from the Qo site, while stigmatellin prevents both phases of the reaction by locking the [2Fe-2S] cluster at the cytochrome b position (24). Remarkably, in both the wild type and the M304/K306 substituted cytochrome bc1 complexes, atovaquone also inhibited both phases like stigmatellin (Fig. 4), indicating that it acted at the Qo site in a manner similar to stigmatellin. Stigmatellin and myxothiazol both block ubihydroquinone binding at the Qo site by occupying portions of the site, but stigmatellin additionally has been shown to inhibit the large amplitude movement of the [2Fe-2S] domain (24, 25) required for electron transfer to cytochrome c1.

Fig. 4.

Reduction kinetics of flash-oxidized cytochrome c in chromatophore samples containing wild type or M304/K306 bc1 complexes. Reactions were initiated by flash activation of the photochemical reaction centers in the chromatophore membranes and recorded as described in the Experimental Procedures. The reaction traces show the reduction of total cytochromes c by ubiquinol in the Qo site via the iron sulfur center (see text). Panel A, Chromatophores containing the wild type R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 complex, in the absence and in the presence of the indicated inhibitors. Panel B, Chromatophores containing the M304/K306 R. capsulatus cytochrome bc1 complex, in the absence and in the presence of the indicated inhibitors.

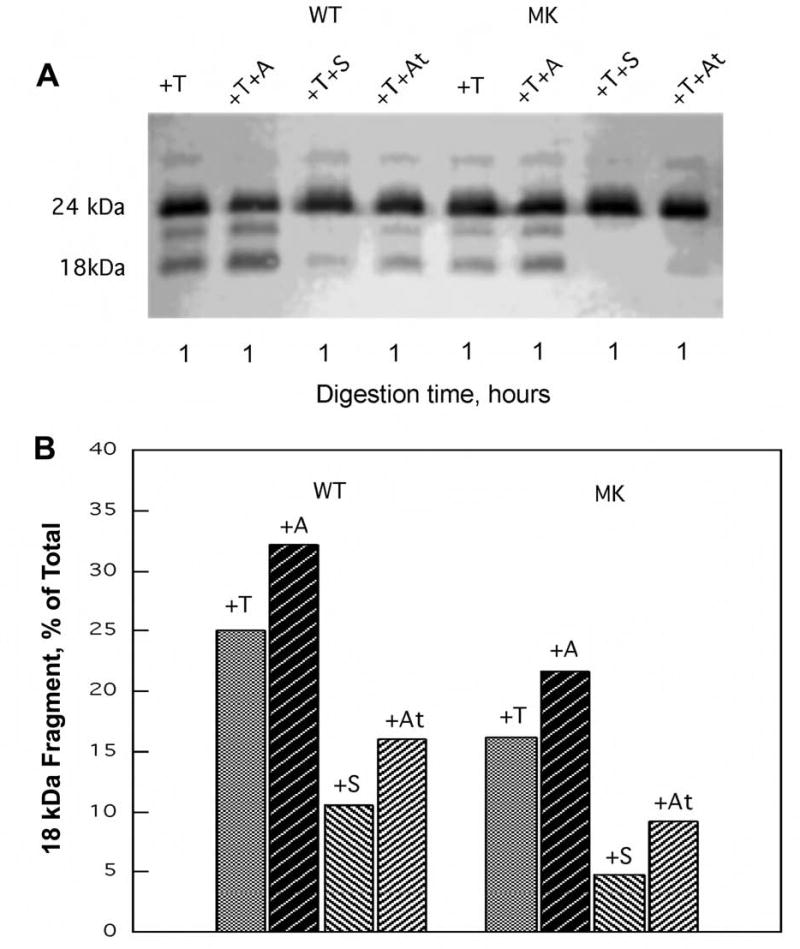

Effect of Atovaquone on the Thermolysin Sensitivity of the Iron-Sulfur Subunit

As the domain immobilization by stigmatellin was shown to be accompanied by decreased sensitivity of the hinge segment of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein to cleavage by thermolysin (24, 25), we examined the thermolysin sensitivity of the cytochrome bc1 complexes in the presence and absence of atovaquone, as well as stigmatellin and antimycin A. Treatment of chromatophores with wild type cytochrome bc1 complexes resulted in conversion of about 25% of the [2Fe-2S] protein to the 18 kDa form resulting from thermolysin cleavage (Fig. 5). The proportion of the short form increased to 32% in the presence of the Qi site inhibitor antimycin A. In the presence of stigmatellin, cleavage to the short form was greatly reduced. Atovaquone also reduced the fraction of the 18 kDa form produced, but to a slightly lesser extent than with stigmatellin. With the cytochrome bc1 complex carrying the M304/K306 mutations, a somewhat lesser degree of conversion to the 18 kDa peptide was found, but the relative amounts observed in the presence of each inhibitor followed the same pattern. We have found that the total amount of conversion to the 18 kDa form varies somewhat from run to run, but the relative amounts obtained for each condition within an experiment, using the same solutions, run in the same gel, and blotted and developed together, are largely consistent. In the case of both wild type and M304/K306 mutations, antimycin A caused a slight increase in the amount of 18 kDa peptide produced, as described earlier (25), while addition of stigmatellin and atovaquone greatly reduced the amount of cleavage product.

Fig. 5.

Susceptibility of wild type and M304/K306 bc1 complexes to proteolysis by thermolysin. Chromatophore samples (650 μg protein) were incubated with 2 nmoles of thermolysin (T) in the absence of inhibitor and in the presence of 30 nmoles of antimycin A (A), stigmatellin (S), or atovaquone (At), under the conditions described in the Experimental Procedures. The upper panel (A) shows the results of SDS-PAGE / Western immunoblot of the Iron sulfur protein in an aliquot of each sample. The lower panel (B) displays the fraction of the proteolytic 18 kDa fragment present in each sample as determined by densitometric analysis (see ref. 24). WT = chromatophores from wild type bacteria; MK = chromatophores from bacteria expressing the I304M/R306K substituted cytochrome b.

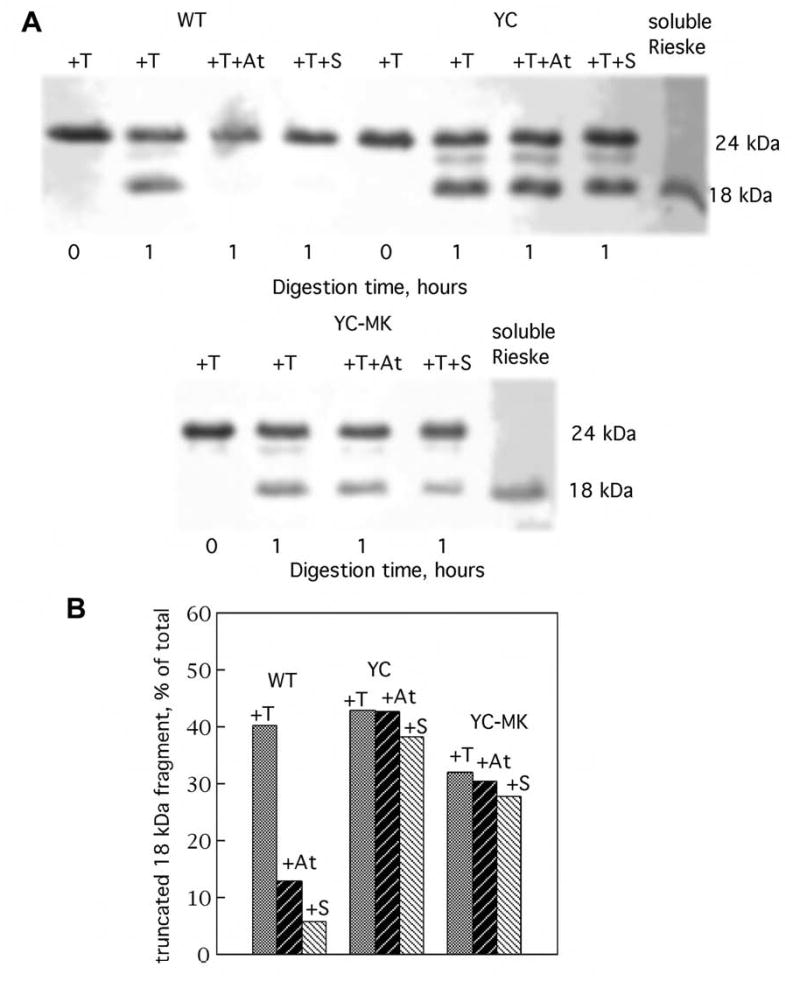

We also examined the thermolysin sensitivity of the [2Fe-2S] protein in the C302-containing complexes, in the absence and presence of stigmatellin and atovaquone, to assess domain mobility. As before, the presence of stigmatellin or atovaquone greatly reduced the susceptibility of the hinge segment in the wild type cytochrome bc1 complex to proteolysis (Fig. 6). In contrast, the addition of stigmatellin or atovaquone to the C302-substituted enzymes did not provide protection from proteolysis (Fig. 6). Thus, with Cys at position 302 of cytochrome b, atovaquone and stigmatellin are no longer able to stabilize the thermolysin-insensitive conformation of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein.

Fig. 6.

Susceptibility of wild type, C302, and M304/K306/C302 cytochrome bc1 complexes to proteolysis by thermolysin. Chromatophore samples (650 μg protein) were incubated with 2 nmoles of thermolysin (T) in the absence of inhibitor and in the presence of 30 nmoles of atovaquone (At) or stigmatellin (S), under the conditions described in the Experimental Procedures. The upper panel (A) shows the results of SDS-PAGE / Western immunoblot of the Iron sulfur protein in an aliquot of each sample. The lower panel (B) displays the fraction of the proteolytic 18 kDa fragment present in each sample as determined by densitometric analysis (see ref. 24). WT = chromatophores from wild type bacteria; C = chromatophores from bacteria expressing the Y302C substituted cytochrome b; CMK = chromatophores from bacteria expressing cytochrome b with the combined Y302C, I304M and R306K substitutions.

DISCUSSION

R. capsulatus has a long history as a useful system for the investigation of cyclic photosynthesis, including the function of the cytochrome bc1 complex, utilizing a combination of techniques, notably genetic and biochemical-biophysical methods (37). Employing these techniques together with the use of ubiquinone-like inhibitors, investigators identified the principal amino acid residues of cytochrome b that interact with ubihydroquinone/ubiquinone, i.e. the residues of the ubiquinone binding pockets, Qo and Qi, prior to the recent solution of the three-dimensional structure of the cytochrome bc1 complex. Since atovaquone is a ubiquinone antagonist to which R capsulatus, like Plasmodium, is relatively sensitive, we have employed this well-developed system to investigate the molecular basis of the drug’s action. The high degree of identity of the region of the Plasmodium cytochrome b that was previously identified as a likely atovaquone interaction site (9) with the corresponding region of the bacterial cytochrome further enhances the utility of the bacterial system for this work. Only two additional changes of the bacterial sequence (I304M and R306K) were required to achieve the complete recapitulation of the 15 residue segment (positions 258 – 272, reproduced in Fig. 1) of the parasite cytochrome b that includes all of the sites at which we found high-level resistance mutations in a previous study involving the generation of atovaquone-resistant P. yoelii parasites (9). This segment also includes the known site of mutations in P. falciparum cytochrome b (Tyr-268, corresponding to Y302 in R. capsulatus numbering) that have been correlated with high-level clinical resistance (8, 14). Trumpower and colleagues have recently developed the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex as a model for fungal and parasite enzyme complexes (38, 39), however, the yeast cytochrome b appears to be more similar to that of fungal pathogens, such as Pneumocystis than to that of apicomplexan parasites.

As we had hypothesized, the M304/K306 double substitution increased the sensitivity of the bacterial cytochrome bc1 complex to atovaquone, but not to stigmatellin or myxothiazol. This effect was modest, a three-fold decrease in the IC50 for atovaquone, as the wild type enzyme complex is already relatively sensitive to the drug. Except for interactions with atovaquone, the biochemical and biophysical properties of the M304/K306 cytochrome bc1 complex were very similar to those of the wild type complex. The steady state enzymatic activity in chromatophore membranes was reduced by about 20%, and the response to inhibitors in the single turnover, flash kinetics experiments was essentially identical to that of the wild type enzyme. The differences in the EPR spectra of the M304/K306 versus the wild type cytochrome bc1 complex were minor, again except in the presence of atovaquone, where a significant sharpening and upfield shift of the gx signal was seen in the M304/K306 samples. The M304/K306 enzyme complex also behaved similarly to the wild type complex with regard to digestion with thermolysin in the presence and absence of inhibitors (discussed further below). Taken together, these results suggest a more pronounced interaction between atovaquone and the [2Fe-2S] cluster at the Qo site of the M304/K306 cytochrome bc1 complex, which may explain the greater sensitivity of this complex to the drug.

Our hypothesis regarding the reproduction of the resistance-associated mutation Y268C (Y302C in the R. capsulatus cytochrome b) was also borne out by the experimental results. In both the wild type and the M304/K306 cytochrome b backgrounds, the inhibitor titration curves shifted by about two orders of magnitude toward increased tolerance of atovaquone, while much smaller changes (a few folds) were observed for stigmatellin and myxothiazol. This was accompanied by about a 10-fold loss of steady state enzymatic activity. The combination of reduced activity and reduced susceptibility to atovaquone suggests that the Y302C substitution lowers the affinity of the cytochrome bc1 complex for the substrate ubihydroquinone, as well as for the inhibitor atovaquone. The results of EPR measurements with the C302 complexes support this suggestion, as the gx transitions remain very broad, even in the presence of atovaquone, which is consistent with a significantly reduced or altered interaction of the [2Fe-2S] cluster with the drug. Moreover, the results of the thermolysin digestion experiments are also consistent with reduced interaction of atovaquone with the C302-containing enzyme complexes. The hinge region of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein of the cytochrome bc1 complex is normally susceptible to cleavage by thermolysin, but in the presence of stigmatellin, the hinge segment is locked into a fully extended conformation that is resistant to cleavage. In this work, we have shown that atovaquone also protects the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein in the wild type and M304/K306 complexes from proteolysis. In the case of the C302-substituted complexes, however, atovaquone or stigmatellin provided little protection from thermolysin cleavage, suggesting greatly reduced or significantly altered modes of interaction.

The results of the thermolysin proteolysis experiments and the single-turnover kinetics with the wild type and M304/K306 cytochrome bc1 complexes suggest similarities in the mechanism of inhibition of atovaquone to that of stigmatellin. Both inhibitors blocked both the rapid and slow phases of electron transfer to cytochrome c, and both provided protection from cleavage of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein by thermolysin, unlike the other Qo site inhibitor myxothiazol, which has a distinctly different effect in these assays. In crystals of mammalian and yeast cytochrome bc1 complexes formed in the presence of stigmatellin or UHDBT, the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein is stabilized in a conformation with its [2Fe-2S] cluster-binding domain in contact with the ef loop region of cytochrome b, and its hinge region in an uncoiled, extended form (16–18). This conformation was found to be a fixed, immobilized one, which thus prevents electron transfer to cytochrome c. Apparently, the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein–cytochrome b contacts in the Qo site involved only two residues in the ef loop of cytochrome b, which contact two residues of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] subunit near its metal cluster, plus a hydrogen bond between one of its cluster ligands, His 156 (R. capsulatus numbering), and the carbonyl group of the chromone ring of stigmatellin. Atovaquone may bind in the Qo site in a manner similar to stigmatellin, with an oxygen atom from a carbonyl or hydroxyl group of the hydroxynaphthoquinone ring forming a hydrogen bond with the histidine ligand of the [2Fe-2S] cluster. In fact, Kessl et al (39) recently constructed an energy-minimized model of atovaquone bound in the Qo site of yeast cytochrome bc1 complex, which predicts that the drug binds to the yeast enzyme in this fashion with a hydrogen bond between the hydroxynaphthoquinone hydroxyl oxygen and a nitrogen atom of the histidine ligand. Clearly though, there are differences in the interactions of atovaquone and stigmatellin with the cytochrome bc1 complex, as evidenced by differences in the EPR spectra and the fact that the engineered Y302C mutation drastically increases resistance to atovaquone, but has little affect on that to stigmatellin. Most interestingly, although stigmatellin remains an inhibitor of the C302-substituted complex, it no longer protects against thermolysin cleavage of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein. In this regard, we note that the crystallographic data show that the Y302 residue participates in forming the binding site of stigmatellin (18, 34, 40). Thus, while stigmatellin still binds strongly to the C302-substituted complex, the interaction of the [2Fe-2S] cluster domain of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein subunit with the bound drug or the ef loop of cytochrome b appears to have been significantly weakened.

P. yoelii and R. capsulatus are phylogenetically distant species, but, as we have noted, the cytochrome bc1 complexes from both are strongly inhibited by atovaquone, while vertebrate cytochrome bc1 complexes are naturally resistant. The sensitivity of the malarial and bacterial enzymes to atovaquone appears to correlate with their high degree of sequence similarity in the ef loop of cytochrome b (Fig. 1). When atovaquone is bound in the Qo site of these sensitive cytochrome bc1 complexes, the [2Fe-2S] cluster domain of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein tends to be immobilized in a cytochrome b-binding conformation. Immobilization prevents electron transfer from the [2Fe-2S] cluster to cytochrome c1. Thus, the mechanism of inhibition by atovaquone may be two-fold, like that of stigmatellin. First, binding of atovaquone within the Qo site probably excludes binding of the substrate ubihydroquinone. Secondly, binding may prevent or greatly slow electron transfer through its effect on the mobility of the cluster domain of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] protein subunit. Yet the interactions of atovaquone with the Qo site may be different than those of stigmatellin, as evidenced by the titration and EPR results.

Finally, it is noted that the substitution Y302C, which is homologous to a point mutation associated with resistance to atovaquone in malaria parasites, has a strong affect on the interactions of atovaquone with the bacterial enzyme as well. The IC50 is raised over 2 orders of magnitude, and the ability to immobilize the [2Fe-2S] cluster domain of the enzyme is lost. The distinctive features of the EPR spectrum in the presence of atovaquone are also lost. The substitution also affects the interaction of other inhibitors and the substrate ubihydroquinone with the Qo site, at the expense of decreasing the steady-state activity of the cytochrome bc1 complex. The direct generation of these effects by site-directed mutagenesis in a defined system should dispel any doubt that the homologous substitution is the direct cause of resistance in the parasite.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI28398 to A.B.V. and GM38237 to F.D.).

The abbreviations used are: EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance; Qo, ubihydroquinone oxidation site; Qi, ubiquinone reduction site; UHDBT, 5-n-undecyl-6-hydroxy-4,7-dioxobenzothiazole; [2Fe-2S], two iron-two sulfur (cluster).

References

- 1.Sachs J, Malaney P. Nature. 2002;415:680–685. doi: 10.1038/415680a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloland, P. B. (2001), pp. 32, World Health Organization

- 3.Chiodini PL, Conlon CP, Hutchinson DB, Farquhar JA, Hall AP, Peto TE, Birley H, Warrell DA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36 :1073–1078. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looareesuwan S, Viravan C, Webster HK, Kyle DE, Hutchinson DB, Canfield CJ. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:62–66. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Looareesuwan S, Chulay JD, Canfield CJ, Hutchinson DB. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:533–541. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling J, Baird JK, Fryauff DJ, Sismadi P, Bangs MJ, Lacy M, Barcus MJ, Gramzinski R, Maguire JD, Kumusumangsih M, Miller GB, Jones TR, Chulay JD, Hoffman SL. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:825–833. doi: 10.1086/342578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy MD, Maguire JD, Barcus MJ, Ling J, Bangs MJ, Gramzinski R, Basri H, Sismadi P, Miller GB, Chulay JD, Fryauff DJ, Hoffman SL, Baird JK. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35 :e92–95. doi: 10.1086/343750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fivelman QL, Adagu IS, Warhurst DC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4097–4102. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4097-4102.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava IK, Morrisey JM, Darrouzet E, Daldal F, Vaidya AB. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33 :704–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fry M, Pudney M. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43 :1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava IK, Rottenberg H, Vaidya AB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272 :3961–3966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava IK, Vaidya AB. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43 :1334–1339. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fivelman QL, Butcher GA, Adagu IS, Warhurst DC, Pasvol G. Malar J. 2002;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korsinczky M, Chen N, Kotecka B, Saul A, Rieckmann K, Cheng Q. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44 :2100–2108. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2100-2108.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Syafruddin D, Siregar JE, Marzuki S. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;104 :185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Huang L, Shulmeister VM, Chi YI, Kim KK, Hung LW, Crofts AR, Berry EA, Kim SH. Nature. 1998;392:677–684. doi: 10.1038/33612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Xia D, Yu CA, Xia JZ, Kachurin AM, Zhang L, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95 :8026–8033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunte C, Koepke J, Lange C, Rossmanith T, Michel H. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8 :669–684. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry EA, Huang LS, Saechao LK, Pon NG, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. Photosynthesis Research. 2004;81 :251–275. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000036888.18223.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trumpower BL, Gennis RB. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63 :675–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schutz M, Brugna M, Lebrun E, Baymann F, Huber R, Stetter KO, Hauska G, Toci R, Lemesle-Meunier D, Tron P, Schmidt C, Nitschke W. J Mol Biol. 2000;300 :663–675. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darrouzet E, Cooley JW, Daldal F. Photosynthesis Research. 2004;79 :25–44. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000011926.47778.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry EA, Guergova-Kuras M, Huang LS, Crofts AR. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69 :1005–1075. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darrouzet E, Valkova-Valchanova M, Moser CC, Dutton PL, Daldal F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4567–4572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valkova-Valchanova M, Darrouzet E, Moomaw CR, Slaughter CA, Daldal F. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15484–15492. doi: 10.1021/bi000751d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao K, Yu L, Yu CA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275 :38597–38604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atta-Asafo-Adjei E, Daldal F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:492–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beatty JT, Gest H. Archives of Microbiology. 1981;129 :335–340. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray KA, Dutton PL, Daldal F. Biochemistry. 1994;33 :723–733. doi: 10.1021/bi00169a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myllykallio H, Zannoni D, Daldal F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96 :4348–4353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saribas AS, Valkova-Valchanova M, Tokito MK, Zhang Z, Berry EA, Daldal F. Biochemistry. 1998;37 :8105–8114. doi: 10.1021/bi973146s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zannoni D, Venturoli G, Daldal F. Archives of Microbiology. 1992;157:367 – 374. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daldal F, Tokito MK, Davidson E, Faham M. Embo J. 1989;8 :3951–3961. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esser L, Quinn B, Li YF, Zhang M, Elberry M, Yu L, Yu CA, Xia D. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding H, Robertson DE, Daldal F, Dutton PL. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3144–3158. doi: 10.1021/bi00127a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding H, Moser CC, Robertson DE, Tokito MK, Daldal F, Dutton PL. Biochemistry. 1995;34 :15979–15996. doi: 10.1021/bi00049a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darrouzet E, Moser CC, Dutton PL, Daldal F. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26 :445–451. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01897-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessl JJ, Hill P, Lange BB, Meshnick SR, Meunier B, Trumpower BL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279 :2817–2824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessl JJ, Lange BB, Merbitz-Zahradnik T, Zwicker K, Hill P, Meunier B, Palsdottir H, Hunte C, Meshnick S, Trumpower BL. J Biol Chem. 2003;278 :31312–31318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crofts AR, Guergova-Kuras M, Kuras R, Ugulava N, Li J, Hong S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459 :456–466. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]