Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the long-term outcome of patients with esophageal cancer after resection of the extraesophageal component of the neoplastic process en bloc with the esophageal tube.

Summary Background Data

Opinions are conflicting about the addition of extended resection of locoregional lymph nodes and soft tissue to removal of the esophageal tube.

Methods

Esophagectomy performed en bloc with locoregional lymph nodes and resulting in a real skeletonization of the nonresectable anatomical structures adjacent to the esophagus was attempted in 324 patients. The esophagus was removed using a right thoracic (n = 208), transdiaphragmatic (n = 39), or left thoracic (n = 77) approach. Lymphadenectomy was performed in the upper abdomen and lower mediastinum in all patients. It was extended over the upper mediastinum when a right thoracic approach was used and up to the neck in 17 patients. Esophagectomy was carried out flush with the esophageal wall as soon as it became obvious that a macroscopically complete resection was not feasible. Neoplastic processes were classified according to completeness of the resection, depth of wall penetration, and lymph node involvement.

Results

Skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy was feasible in 235 of the 324 patients (73%). The 5-year survival rate, including in-hospital deaths (5%), was 35% (324 patients); it was 64% in the 117 patients with an intramural neoplastic process versus 19% in the 207 patients having neoplastic tissue outside the esophageal wall or surgical margins (P < .0001). The latter 19% represented 12% of the whole series. The 5-year survival rate after skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy was 49% (235 patients), 49% for squamous cell versus 47% for glandular carcinomas (P = .4599), 64% for patients with an intramural tumor versus 34% for those with extraesophageal neoplastic tissue (P < .0001), and 43% for patients with fewer than five metastatic nodes versus 11% for those with involvement of five or more lymph nodes (P = .0001).

Conclusions

The strategy of attempting skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy in all patients offers long-term survival to one third of the patients with resectable extraesophageal neoplastic tissues. These patients represent 12% of the patients with esophageal cancer suitable for esophagectomy and 19% of those having neoplastic tissue outside the esophageal wall or surgical margins.

According to Logan, 1 it is possible to take one of two views concerning cancer surgery: “that cure is possible only when the tumor remains confined to the structure in which it takes origin or that cure may still be possible when the tumor has directly extended to the immediate adjacent tissues or has spread to closely related lymph glands.” In terms of esophageal cancer, advocates of the first option 2 restrict the surgical procedure to removal of the esophageal tube without any attempt to resect potentially involved adjacent lymph nodes. In contrast, proponents of the second option perform so-called radical esophagectomies including removal of related lymph nodes, either en bloc with the primary 3–8 or separately. 9 Any attempt to compare the two options in terms of long-term survival is illusive because of the lack of staging according to N factor with the former procedure.

A possible way to evaluate the usefulness of resection of the extraesophageal component of the neoplastic process is to assess the long-term outcome of patients in whom resectable locoregional lymph nodes and soft tissues have been removed rather than abandoned in the surgical field. In this respect, we know from the experience of different surgical teams 3–8 that neoplastic spread beyond the esophageal wall does not preclude long-term survival and cure. In particular, Akiyama’s team in Japan 9 has shown that the 5-year survival rate in such patients may be as high as 27% after thoracoabdominal lymph node clearance and 43% after colothoracoabdominal dissection.

The present article reports a single-center experience of 324 consecutive white patients with cancer of the esophagus or cardia in whom skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy (SEBE) was attempted to circumscribe some of the neoplastic processes that had already spread outside the esophageal wall.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The study includes, without exception, the 324 esophagectomies performed for cancer of the esophagus (n = 240) or cardia (n = 84) by the first author (J.M.C.) between October 1984 and November 1997. Patients were 249 men and 75 women, ages 33 to 85 years. From a histologic standpoint, there were 160 squamous cell carcinomas, 158 adenocarcinomas, 1 basaloid carcinoma, 1 lymphoma, 1 melanoma, 2 sarcomas, and 1 oat cell carcinoma.

Preoperative Workup

Initial workup included upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsies, barium swallow study, standard chest radiographs, computed tomography scan of the neck, chest, and abdomen, liver ultrasonography, and more recently endosonography. With the exception of some suspected T4 upper-half tumors in which first-line chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was given for downstaging, the surgical option was retained even though there was a suspicion of extraesophageal neoplastic spread at initial workup.

Surgical Technique

The basic principle of surgical technique was the removal of the esophageal tube en bloc with locoregional soft tissue and lymph nodes. 1,3 Surgical dissection was carried out flush with the nonresectable anatomical structures adjacent to the esophagus, resulting in a real skeletonization of the posterior mediastinum and upper abdomen, as seen in textbooks of anatomy. A single block of tissue was given to the pathologist at the end of the procedure and immediately immersed in formalin. Esophageal resection was considered potentially curative 10 whenever the neoplastic process could be removed in totality from a macroscopic standpoint and surgical margins were cancer-free at histology (R0). It was considered palliative if there were positive margins at histology (R1) and whenever a part of the neoplastic process could not be removed (R2). In the latter instance, resection was completed flush with the esophageal tube. In practice, the esophagus was removed using one of three surgical approaches.

Right Thoracic Approach

Three-stage esophagectomy by right thoracotomy (n = 198) or thoracoscopy 11 (n = 10), laparotomy, and cervicotomy was the first-choice approach to tumors in the esophageal tube. This approach was also used in seven cardia cancers that extended far in the esophagus. Potentially curative resection of the esophagus is made en block with locoregional lymph nodes from the apex of the chest to the hiatus as well as with soft tissues covering the descending aorta, the trachea and mainstem bronchi, the pulmonary veins, and the pericardium. The lower segment of the thoracic duct up to where it crosses behind the esophagus, and the right azygous vein up to its arch are included in the bloc while preserving intercostal arteries. However, when the right azygous vein lies far from the esophagus, as in some patients with a prominent descending aorta, dissection is carried out flush with the vein. Likewise, the resection block may contain a pericardiac patch or even the lower lobe of the right lung in the uncommon situation of direct tumor invasion of these structures. The esophagus is divided in the neck and pulled down in the abdomen. Lymph nodes along the celiac axis and its three branches along the left aspect of the portal vein, in front of the inferior vena cava, along the diaphragmatic pillars, and in front of the left adrenal gland are resected en bloc with the esophagus. Seventeen patients with a tumor arising in the esophageal tube (i.e., squamous in 15, adenomatous in 1, and sarcomatous in 1) underwent three-field lymphadenectomy 9 including bilateral lymph node dissection in the neck.

Transdiaphragmatic Approach

The transdiaphragmatic approach to the esophagus without thoracotomy (n = 39) was mainly used in patients who had both a lower-third tumor and concomitant conditions such as respiratory insufficiency, advanced age, or poor general status that precluded thoracotomy. In patients undergoing surgery with a curative intent, extensive lymph node clearance in the upper abdomen is followed by a posterior-inferior mediastinectomy, 12 which is facilitated by making a radial incision in the diaphragm forward to the hiatus according to Pinotti’s technique. 13 For this, two Polosson retractors are used to retract the two crura and the lower lobe of each lung laterally and the heart forward. The hiatus itself is best exposed by retracting the abdominal wound edges with two Weinberg-like retractors that attach to two posts located on each side of the patient’s chest. Then, mediastinal dissection is carried out flush with the lower thoracic aorta and pericardium up to the lower pulmonary veins or even the tracheal bifurcation rather than close to the lower thoracic esophagus, as is the case with conventional blunt esophagectomy through the hiatus. 2 Both pleural sheaths are removed en bloc with the lower thoracic esophagus and all lymph nodes and soft tissues in the lower mediastinum. The upper half of the esophagus is resected by blunt finger dissection close to the wall. In the presence of a huge tumor at the thoracic inlet level (n = 4) or in the uncommon situation of a subtotal esophagectomy combined with a coronary bypass procedure (n = 2), the incision also included median sternotomy.

Left Thoracic Approach

The left thoracic approach 3,14 was used in 77 of the 84 patients who had a cardia cancer. The left pleural cavity is entered through the seventh interspace, and the anterior part of the diaphragm is opened peripherally from beneath the sternum to the splenic area. The parietal incision is extended over the left upper quadrant of the abdomen to the midline. In patients undergoing surgery with a curative intent, the block of tissue including the lower segment of the thoracic esophagus is dissected off the descending aorta, the right mediastinal pleura, the pericardium, and the left pulmonary veins. The internal margin of the hiatal sling, 2 or 3 mm thick, is resected en bloc with the tumor. The esophagus is divided at the level of the left pulmonary veins or of the left bronchus. The lower segment of the esophagus is retracted below the diaphragm through the hiatus to facilitate perigastric dissection and lymph node clearance of the upper abdomen. Basically, the stomach was removed in totality (n = 50). However, gastrectomy was limited to the proximal third of the stomach (n = 27) in patients undergoing palliative surgery or in some debilitated patients undergoing surgery with a curative intent.

Radical lymph node dissection was performed in the upper abdomen and lower mediastinum in all patients undergoing surgery with a curative intent. It was extended to the upper mediastinum in those in whom the right thoracic approach was used and to the neck in 17 patients, most of these having an upper-half tumor. The esophageal anastomosis was performed in the neck (n = 247) or in the chest (n = 77). Digestive continuity was restored with the stomach 15,16 (n = 265), the jejunum (n = 50), or the colon (n = 9).

Additional Treatment

Thirty-six patients undergoing surgery with a curative intent received multimodal treatment that combined surgery with preoperative (n = 7) or postoperative (n = 29) radiotherapy (45 Gy) and/or chemotherapy (two to six courses of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin). Preoperative treatment was mainly given to patients having a suspected T4 upper-half tumor; postoperative nonsurgical therapy addressed some of the patients who underwent surgery in the 1980s and early 1990s (a time when little was known about the potential benefit in terms of long-term survival one could expect from the addition of nonsurgical therapies to surgery).

Data Analysis

The 324 neoplastic processes were classified into three categories according to completeness of the resection, the depth of wall penetration, and lymph node involvement 3 : those that were resectable in totality and remained confined to the esophageal wall, those that were resectable in totality although they had spread outside the esophageal wall, and those that had spread outside surgical margins. Patients in the second category were further subdivided according to whether fewer than five or five or more regional lymph nodes were metastatic. 3

Survival curves were established 18 months after the last surgical procedure using the Kaplan-Meier method. 17 Patients were followed up until their death or the time of the study (mean follow-up 34.2 months, range 3 days to 165 months). Survival curves were compared with respect to completeness of the resection (R0 vs. R1, R2), T and N factors, 18 main histologic types (squamous cell vs. adenocarcinoma), and modes of therapy (exclusively surgical vs. multimodal) using the log-rank test. All survival rates included in-hospital deaths except those based on the mode of therapy, because patients who died of a postoperative complication were not suitable for adjuvant therapy. Five-year survival rates in the main subsets of patients were expressed as the mean and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Two-tailed Fisher exact and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. A probability value of less than .05 was considered significant. Data interpretation was based on the assumption that long-term survival is unlikely after resection limited to the esophageal tube and abandonment of extraesophageal neoplastic tissue in the surgical field.

RESULTS

Feasibility

In 235 of the 324 patients (73%), SEBE was feasible, whereas 89 patients (27%) underwent a palliative procedure. The main reasons for palliation were macroscopic involvement of one of the nonresectable structures adjacent to the esophagus (n = 26), lung (n = 6) or liver (n = 9) metastases, diffuse neoplastic spread into either the upper mediastinal (n = 11) or abdominal (n = 16) lymph nodes, tumor perforation (n = 3), a huge tumor mass (n = 6), peritoneal carcinomatosis (n = 7), or a positive esophageal margin (n = 5). The feasibility rate in squamous cell carcinomas was similar to that in adenocarcinomas (74% vs. 72%, P = .7065).

Postoperative Staging

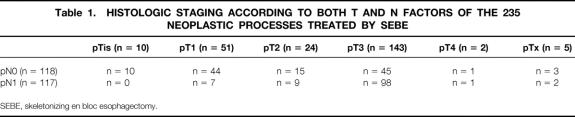

One hundred seventeen neoplastic processes (36%) remained confined to the esophageal wall, 118 (36%) could be resected in totality although they had spread beyond the wall, and 89 (27%) had spread outside surgical margins. As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of patients having metastatic lymph nodes among those who underwent SEBE increased parallel to the T factor (Tis, 0%; T1, 13%; T2, 37%; T3, 68%;P < .0001). Among the 17 patients who underwent three-field lymphadenectomy, 6 (35%) had metastatic lymph nodes in the neck. Five of these six patients also had positive nodes in the chest or the abdomen. Moreover, 1 of the 17 patients had neoplastic cells in a very small lung nodule (R2 resection) and another had positive margins (R1 resection) on postoperative histologic examination, whereas intraoperative frozen sections were negative.

Table 1. HISTOLOGIC STAGING ACCORDING TO BOTH T AND N FACTORS OF THE 235 NEOPLASTIC PROCESSES TREATED BY SEBE

SEBE, skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy.

Survival

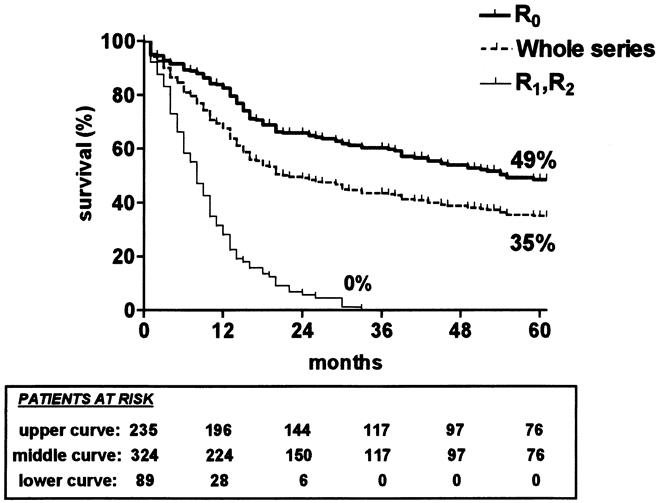

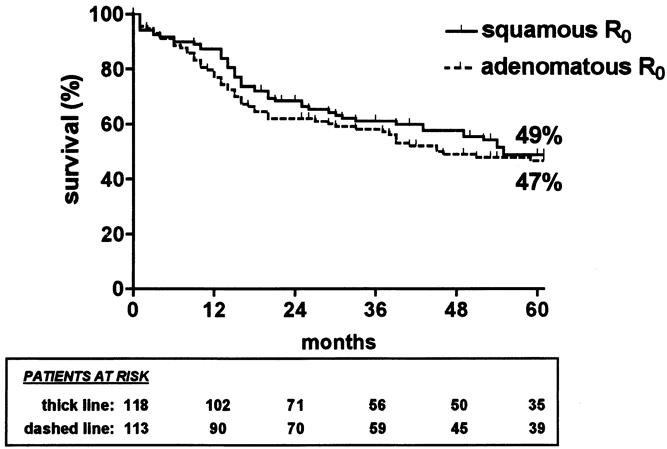

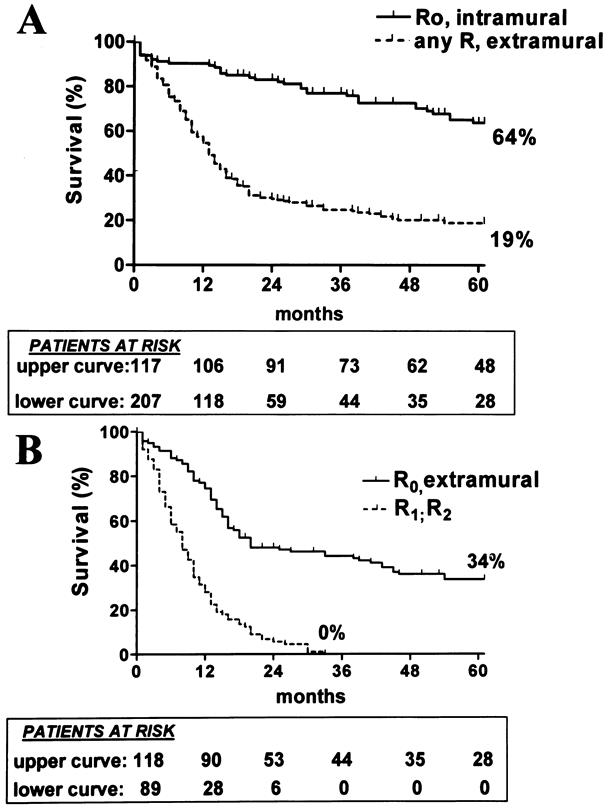

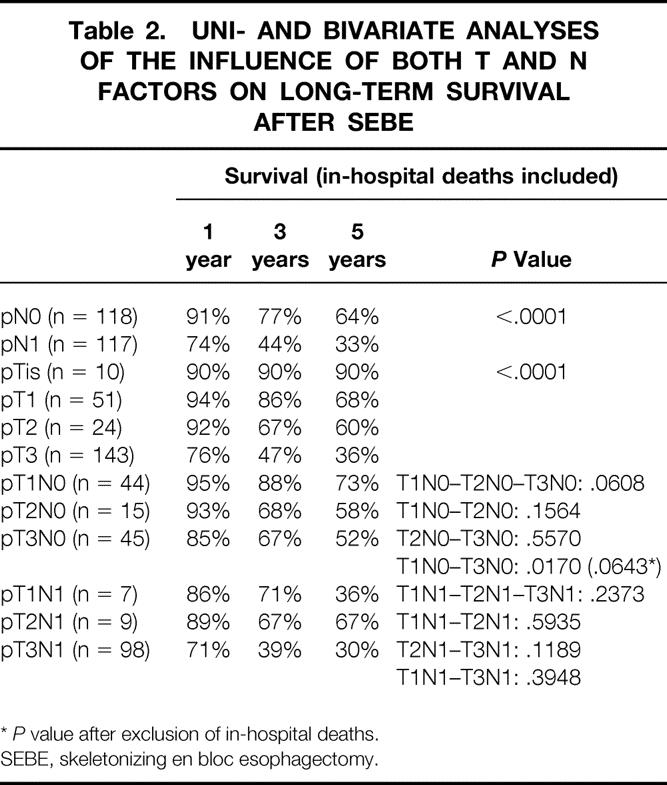

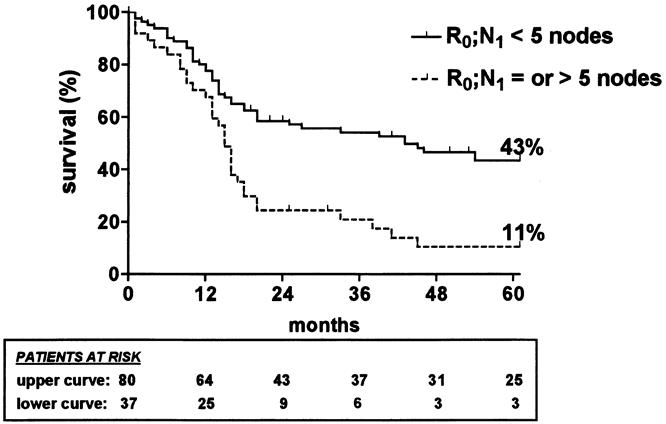

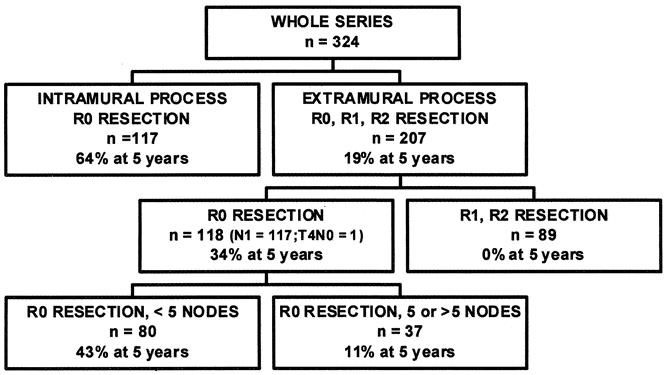

The 5-year survival rate, including in-hospital deaths (5%), was 35% (95% CI, 30–40%) in the whole series, 49% (42–56%) after SEBE, and 0% after incomplete (R1, R2) resection (Fig. 1). The 5-year survival in the whole series was 36% (28–44%) for squamous cell carcinomas versus 33% (26–40%) for adenocarcinomas (P = .4812) and increased after SEBE to 49% (39–59%) and 47% (37–57%), respectively (P = .4599) (Fig. 2). In the whole series (Fig. 3), it was 64% (54–74%) for the 117 patients who had a totally resectable intramural neoplastic process (R0; Tis through T3; N0) versus 19% (13.5–24.5%) for the 207 patients whose neoplastic process had spread outside the esophageal wall or surgical margins (R0, any TN1; R0T4N0; R1; R2) (P < .0001). The latter 19% represented 12% of the whole series of 324 patients. As shown in Figure 3, the 5-year survival rate was 34% (25–43%) when the extraesophageal component of the neoplastic process was resectable in totality (R0, any TN1; R0T4N0) versus 0% when it was not (R1; R2) (P < .0001). Univariate analysis (Table 2) shows that survival after SEBE was closely related to the depth of wall penetration and lymph node involvement. However, bivariate analysis showed that the T factor influenced survival because of a higher prevalence of metastatic lymph nodes in transmural (T3) than in nontransmural (Tis; T1; T2) tumors. Indeed, two-by-two comparison of the different subgroups failed to show any significant difference, except for T1N0 versus T3N0 tumors (P = .0170). However, after exclusion of the in-hospital deaths, the latter difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .0643). In contrast, the 5-year survival rate after SEBE was 43% (32–54%) in patients having fewer than five metastatic lymph nodes versus 11% (0–31%) in those with five or more metastatic nodes (P = .0001) (Fig. 4). Five-year survival rates in the main subsets of patients are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival (in-hospital deaths included) of the 324 patients who underwent surgery (whole series) (dashed line), the 235 patients in whom skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy was feasible (R0) (thick line), and the 89 patients in whom it was not (R1/R2) (thin line).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival (in-hospital deaths included) of patients with squamous cell carcinoma (thick line) and of patients with adenocarcinoma (dashed line) in whom skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy was feasible.

Figure 3. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival (in-hospital deaths included) of patients having a resectable intramural neoplastic process (R0, intramural) and of those with a neoplastic process that had spread outside the esophageal wall or surgical margins (any R, extramural). (B) Splitting of the lower curve of (A) according to whether the extramural component of the neoplastic process was resectable in totality (R0, extramural) or not (R1, R2).

Table 2. UNI- AND BIVARIATE ANALYSES OF THE INFLUENCE OF BOTH T AND N FACTORS ON LONG-TERM SURVIVAL AFTER SEBE

*P value after exclusion of in-hospital deaths.

SEBE, skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy.

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier survival (in-hospital deaths included) after skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy in patients with fewer than five metastatic lymph nodes (thick line) and in those with five or more metastatic lymph nodes (dashed line).

Figure 5. Summary of 5-year survival rates in the main subsets of patients.

Although neoadjuvant or adjuvant nonsurgical therapies were not given in a randomized fashion, retrospective analysis of the small group of patients given combined treatment and of the large group of patients exclusively treated by esophageal resection indicated that the prevalence of diseases metastatic to locoregional lymph nodes was similar in the two groups: 53% and 49%, respectively (P = .7207). Comparison of these two groups with respect to survival failed to show any statistically significant difference: the 5-year survival rate was 43% (95% CI, 27–59%) and 53% (45–61%), respectively (P = .4129).

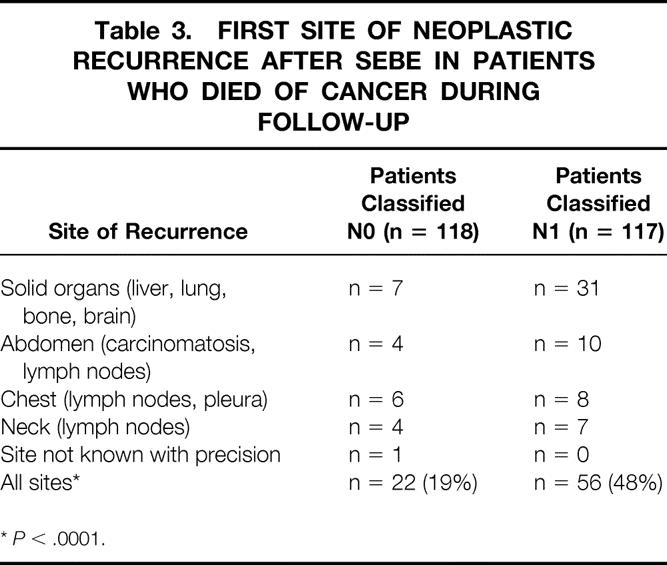

Among the 235 patients in whom SEBE was feasible, 18 patients died of an unrelated cause, 3 of an unknown cause, and 78 of neoplastic recurrence during the follow-up period. Of these 78 patients, 22 had been classified N0 (22/118; 19%) and 56 N1 (56/117; 48%) at postoperative pathologic examination of the resected specimen (Table 3). Neoplastic recurrence in 14 of these 78 patients (18%) occurred more than 3 years after surgery. Metastatic lymph nodes developed in the neck of 11 patients (4%), among whom 2 had had three-field lymphadenectomy. Cervical metastases also developed after three-field dissection in one patient who eventually underwent a palliative procedure because of a metastatic lung nodule at postoperative histologic examination. This makes a total of 3 patients who had neoplastic recurrence in the neck among the 17 patients who underwent cervical lymphadenectomy (17%). Seventeen patients (7%), of whom 14 had died and 3 were living at the time of the study, had local neoplastic recurrence in the chest after SEBE.

Table 3. FIRST SITE OF NEOPLASTIC RECURRENCE AFTER SEBE IN PATIENTS WHO DIED OF CANCER DURING FOLLOW-UP

*P < .0001.

DISCUSSION

Long-term survival of patients with esophageal cancer a priori suitable for radical esophagectomy depends on the completeness of the resection, whether the neoplastic process is still confined to the esophageal tube, and the number of metastatic lymph nodes in the resected specimen. Indeed, although one patient in two may anticipate long-term survival when complete (R0) resection has been possible, the long-term outcome of patients in whom a part of the neoplastic process must be left in the dissection field (R1, R2 resections) is very poor:4,19 none of these patients was alive beyond 3 years of follow-up. The 5-year survival rate of 49% achieved after SEBE in the current series confirms figures published by other surgeons after radical esophagectomy including extended thoracoabdominal dissection: for instance, 48% for Lerut et al, 7 41% for Hölscher et al, 12 41% for Hagen et al, 20 38% for Akiyama et al, 9 and 36% for Peracchia and Bonavina. 21 Failure to complete the procedure in about one quarter of patients in whom SEBE is attempted is mainly due to the inability of the classic methods of preoperative investigation to predict the existence of nonresectable extraesophageal neoplastic tissue with 100% accuracy. In the near future, more accurate staging and better patient selection for radical surgery might be possible with the use of currently emerging diagnostic tools such as the positron emission tomography technique, provided that promising preliminary results 22 are confirmed.

The long-term outcome after R0 resection in the current series was closely related to the fact that the neoplastic process remained confined to the esophageal wall (64% survival at 5 years) or had already spread into related lymph nodes or had invaded adjacent soft tissues (34% survival at 5 years). In addition, the current study confirms 3,5,6,8 that SEBE is most beneficial in patients who have a limited number of resectable metastatic locoregional lymph nodes, as if the existence of a large number of metastatic nodes testified to the existence of a widespread neoplastic disease that could not be removed by local therapy. The study also confirms that the T factor influences long-term prognosis through a higher prevalence of positive lymph nodes in transmural than in nontransmural tumors. 9,23

Although the presence of neoplastic tissue outside the esophageal wall alters the long-term prognosis substantially, it appears that resection of the extraesophageal component of the neoplastic process with the SEBE technique allows one third of the patients to anticipate long-term survival. We must remember, however, that these patients represent 12% (ie, one patient out of eight) of those who are a priori suitable for esophageal resection and 19% (ie, one patient out of five) of those whose neoplastic process has spread outside the esophageal wall or surgical margins. Despite the lack of a control group of patients treated by resection of the esophageal tube only, it may be assumed that long-term favorable outcome is very unlikely when extraesophageal neoplastic tissue, although resectable, has been left in the surgical field. This is supported by the observation that none of our patients with residual cancer lived 5 years after palliative esophagectomy.

Comparison of survival rates achieved with the SEBE technique with those reported after less radical operations consisting of excision of the esophageal tube with some of the lymph nodes in its immediate vicinity suffers from a lack of phase 3 trials. For want of such trials, the only possible ways to estimate the potential superiority of the SEBE technique over less radical surgery are to consider nonrandomized comparative studies on the one hand, and to look at survival data from very large series of non-en bloc esophagectomies on the other. Therefore, a single-center study comparing two groups of patients with a similar prevalence of tumors invading the full thickness of the wall and lymph nodes 20 showed better survival after SEBE (41% at 5 years) than after conventional transhiatal resection (21% at 5 years). In contrast, mean survival rates of approximately 20% at 5 years in recent very large series of non-en bloc esophagectomies 2,18,24–26 are substantially inferior to the overall survival rate of 35% in our series of 324 patients, among whom 89 had a purely palliative procedure. For instance, survival rates at 5 years in a series of 797 nonradical transhiatal esophagectomies 2 (23%) and in a series of 260 nonradical transthoracic esophageal resections 18 (20%) are outside the 95% confidence interval of the corresponding survival rates in the current series (30–40%). Interestingly, the difference in survival involves not only patients with extraesophageal neoplastic tissue (13.5–24.5% vs. 8–12%) but also those with an intramural disease (54–74% vs. 38%). 2,18 According to the principle that the more extended the resection the more accurate the staging, 9,19 higher survival rates in patients classified as N0 after SEBE may reflect in part better identification of truly intramural disease resulting from removal of metastatic nodes that are left in place after less extended lymphadenectomy. A similar explanation has been given for the improved survival rates of N0 patients after three-field than after two-field dissection:9,19 some patients classified as N0 after two-field dissection but actually having occult metastases in cervical lymph nodes move from one category to the other. In addition, we must remember that histologic examination of a single section of a given lymph node may miss some neoplastic cells located in another part of the node, and that biologic micrometastases may be present in histologically negative lymph nodes. 27,28

Another advantage of SEBE is to minimize the risk of neoplastic recurrence in the chest, which was 7% in the current series and ranged from 5% to 10% in other series from the literature. 4,5,8,19 Indeed, although low rates of intrathoracic recurrence have been reported after esophagectomy with limited periesophageal dissection, 26,29 the rather disappointing figures ranging from 24% to 50% published by other teams 18,30–32 are not observed after SEBE. Rather, regional recurrences after en bloc esophagectomy have been shown to develop mainly outside the dissected area. 5 The discrepancy between local recurrence rates in different series of so-called standard esophagectomies probably reflects technical variations from one team to another with respect to the extent of lymph node clearance, because dissection does not follow precise anatomical landmarks. However, the fact that one neoplastic recurrence out of five in the current series occurred more than 3 years after R0 resection confirms Lerut et al’s observation 19 that SEBE, for want of eradicating the disease, seems to minimize the pool of residual neoplastic cells in some patients. As for nonsurgical therapies, their ability to control local neoplastic disease is poorer. For instance, 42% of patients from Herskovic et al’s series 33 did not experience improvement of their ability to swallow after exclusive radiochemotherapy.

Failure of the policy of attempting SEBE in all patients a priori suitable for esophagectomy to cure 80% of those having extraesophageal neoplastic tissue stresses the need for better therapeutic strategies against locally advanced esophageal cancer. A first option is to perform still more radical surgery by adding extended neck dissection to thoracoabdominal lymph node clearance in all patients. Encouraging data from Japan 9,34 are supported by our own experience of nine patients in whom neoplastic recurrence developed in the neck after two-field lymphadenectomy. However, as illustrated by the clinical outcome of 3 of our 17 patients who underwent three-field dissection, radical cervical lymphadenectomy does not provide full protection against neoplastic recurrence in the neck at follow-up. There is also a discrepancy between different Japanese series 35,36 concerning the real benefit one can expect from cervical dissection once positive lymph nodes are present in the three fields. In addition, according to some authors, 34,35 three-field dissection carries a higher risk of postoperative death and of pulmonary complications requiring temporary tracheostomy. A second option is to combine adjuvant or neoadjuvant nonsurgical treatment such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy with radical surgery. In this respect, no conclusion can be drawn from our experience of combined therapy because it was given in a nonrandomized fashion to a small number of patients. Although recent phase 3 trials 24,25 showed no significant improvement of overall long-term survival by combination of nonsurgical therapies with so-called standard esophagectomy, recent data from Akiyama’s team 37 suggest that the addition of high-dose chemotherapy to very radical surgery might improve the long-term prognosis of patients with resectable squamous cell carcinomas. The poor long-term outcome of patients with a large number of resectable metastatic lymph nodes 3,5,6,8 suggests that these patients might be the best candidates for such an adjuvant treatment. In any case, the rather high survival rates obtained with extended esophageal resection 4–9,12,20,21 make obsolete any attempt to improve the prognosis by adding nonsurgical therapies to a surgical procedure that would not exploit potentialities of the surgical treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Nadine Thiebaut for typing the manuscript and Mrs. Annie Robert, biostatistician.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Jean-Marie Collard, MD, Digestive Surgery Unit, St-Luc Academic Hospital, Hippocrate Avenue, 10, B-1200 Brussels, Belgium.

E-mail: collard@chir.ucl.ac.be

Accepted for publication August 28, 2000.

References

- 1.Logan A. The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus and cardia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1963; 46: 150–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Transhiatal esophagectomy clinical experience and refinements. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner DB. En-bloc resection for neoplasms of the esophagus and cardia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 85: 59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siewert JR, Roder JD. Lymphadenectomy in esophageal cancer surgery. Dis Esoph 1992; 5: 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark GWB, Peeters JH, Ireland A, et al. Nodal metastasis and sites of recurrence after en-bloc esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 58: 646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collard JM, Romagnoli R, Hermans BP, Malaise J. Radical esophageal resection for adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Surg 1997; 174: 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerut T, De Leyn P, Coosemans W, et al. Surgical strategies in esophageal carcinoma with emphasis on radical lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg 1992; 216: 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altorki N, Girardi L, Skinner DB. Extended resections for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus and cardia. In: Peracchia A, Rosati R, Bonavina L, et al, eds. Recent advances in diseases of the esophagus. Bologna: Monduzzi; 1996: 273–279.

- 9.Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Kajiyama Y. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermanek P, Wittekind C. The pathologist and the residual tumor (R) classification. Pathol Res Pract 1994; 190: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collard JM, Lengele B, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. En-bloc and standard esophagectomies by thoracoscopy. Ann Thorac Surg 1993; 56: 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hölscher AH, Bollschweiler E, Bumm R, et al. Prognostic factors of resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Surgery 1995; 118: 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinotti HW, Zilberstein B, Pollara WM, Raia A. Esophagectomy without thoracotomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1981; 152: 344–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiyama H, Miyazono H, Tsurumaru M, et al. Thoracoabdominal approach for carcinoma of the cardia of the stomach. Am J Surg 1979; 137: 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collard JM, Tinton N, Malaise J, et al. Esophageal replacement: gastric tube or whole stomach ? Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 60: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collard JM, Romagnoli R, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. The denervated stomach as an esophageal substitute is a contractile organ. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. JASA 1958; 53: 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Killinger WA, Rice TW, Adelstein DJ, et al. Stage II esophageal carcinoma: the significance of T and N. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 111: 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerut TE, Coosemans W, De Leyn P, et al. Reflections on three-field lymphadenectomy in carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1999; 46: 717–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagen JA, Peters JH, Demeester TR. Superiority of extended en bloc esophagectomy for carcinoma of the lower esophagus and cardia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993; 106: 850–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peracchia A, Bonavina L. Carcinoma del cardias. Rome: Studio Tipografico SP; 1999: 157–172.

- 22.Block MI, Patterson GA, Sundaresan RS, et al. Improvement in staging of esophageal cancer with the addition of positron emission tomography. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 64: 770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice TW, Zuccaro G, Adelstein DJ, et al. Esophageal carcinoma: depth of tumor invasion is predictive of regional lymph node status. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 65: 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelsen DP, Ginsberg R, Pajak TF, et al. Chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone for localized esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1979–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosset JF, Gignoux M, Triboulet JP, et al. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vigneswaran WT, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, et al. Transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg 1993; 56: 838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luketich JD, Kassis ES, Shriver SP, et al. Detection of micrometastases in histologically negative lymph nodes in esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66: 1715–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izbicki JR, Hosch SB, Pichlmeier V, et al. Prognostic value of immuno-histochemically identifiable tumor cells in lymph nodes of patients with completely resected esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1188–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finley RJ, Inculet RI. The results of esophagogastrectomy without thoracotomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg 1989; 210: 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross BH, Agha FP, Glazer GM, Orringer MB. Gastric interposition following esophagectomy: CT evaluation. Radiology 1985; 155: 177–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanz L, Gonzales JJ, Miyar A, et al. Pattern of recurrence after esophageal resection for cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology 1999; 46: 2393–2397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbier PA, Luder PJ, Schupfer G, et al. Quality of life and patterns of recurrence following transhiatal esophagectomy for cancer: results of a prospective follow-up in 50 patients. World J Surg 1988; 12: 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herskovic A, Martz K, Al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 1593–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isono K, Sato H, Nakayama K. Result of a nationwide study on the three-field lymph node dissection of esophageal cancer. Oncology 1991; 48: 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ide H, Hanyu F, Murata Y, et al. Extended dissection for thoracic esophageal cancer based on preoperative staging. In: Ferguson MK, Little AG, Skinner DB, eds. Diseases of the esophagus, vol. 1: Malignant diseases. Mount Kisko, NY: Futura Publishing Co; 1990:177–186.

- 36.Isono K, Okuyama K, Ochiai T. Evaluation of lymphadenectomy of intrathoracic esophageal cancer in terms of patient survival. In: Ferguson MK, Little AG, Skinner DB, eds. Diseases of the esophagus, vol. 1: Malignant diseases. Mount Kisko, NY: Futura Publishing Co; 1990:213–218.

- 37.Udagawa H, Tsurumaru M, Kinoshita M, et al. The effects of postoperative chemotherapy with large dose CCDP and 5-FU on the prognosis after radical esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [abstract]. Can J Gastroenterol 1998; 12 (suppl B): 64. [Google Scholar]