Abstract

Objective

To assess the utility of triage guidelines for patients with cholelithiasis and suspected choledocholithiasis, incorporating selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) before laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC).

Summary Background Data

ERCP is the most frequently used modality for the diagnosis and resolution of choledocholithiasis before LC. MRC has recently emerged as an accurate, noninvasive modality for the detection of choledocholithiasis. However, useful strategies for implementing this diagnostic modality for patient evaluation before LC have not been investigated.

Methods

During a 16-month period, the authors prospectively evaluated all patients before LC using triage guidelines incorporating patient information obtained from clinical evaluation, serum chemistry analysis, and abdominal ultrasonography. Patients were then assigned to one of four groups based on the level of suspicion for choledocholithiasis (group I, extremely high; group 2, high; group 3, moderate; group 4, low). Group 1 patients underwent ERCP and clearance of common bile duct stones; group 2 patients underwent MRC; group 3 patients underwent LC with intraoperative cholangiography; and group 4 patients underwent LC without intraoperative cholangiography.

Results

Choledocholithiasis was detected in 43 of 440 patients (9.8%). The occurrence of choledocholithiasis among patients in the four groups were 92.6% (25/27), 32.4% (12/37), 3.8% (2/52), and 0.9% (3/324) for groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (P < .001). MRC was used for 8.4% (37/440) of patients. Patient triage resulted in the identification of common bile duct stones during preoperative ERCP in 92.3% (36/39) of the patients. Unsuspected common bile duct stones occurred in six patients (1.4%).

Conclusions

The probability of choledocholithiasis can be accurately assessed based on information obtained during the initial noninvasive evaluation. Stratification of risks for choledocholithiasis facilitates patient management with the most appropriate diagnostic studies and interventions, thereby improving patient care and resource utilization.

Gallstone disease poses a major health problem in the United States. More than 600,000 cholecystectomies are performed yearly, with estimated direct costs for the diagnosis and treatment of gallstones exceeding $5 billion annually. 1 Choledocholithiasis is detected in 8% to 20% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy. 2–4 Several options are available for the diagnosis and treatment of choledocholithiasis, but there is no consensus on the optimal management strategy for these patients. 5 The selection of diagnostic and treatment approaches depends on multiple factors, including the level of suspicion for choledocholithiasis, patient and physician preferences, resource availability, and the expertise of the surgeons, endoscopists, and radiologists.

Clinical, ultrasonographic, and serum chemistry data commonly acquired during patient evaluations are sensitive in 96% to 98% and specific in 40% to 75% of the patients for the determination of choledocholithiasis. 2–4 Therefore, when these indicators are used for the selection of patients for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), up to 75% of the patients have no common bile duct (CBD) stones found during the procedure. Even though ERCP is effective for the diagnosis and clearance of CBD stones, this procedure can be associated with patient discomfort, inconvenience, and complications. 6

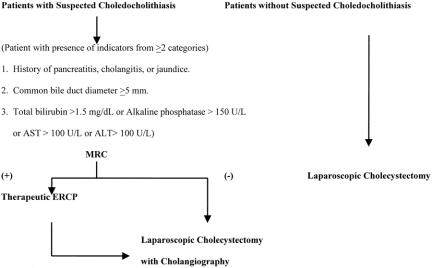

Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) has been shown to possess diagnostic accuracy comparable to that of ERCP. 7–12 In a previous study, we selected patients for MRC imaging on the basis of clinical evaluation, serum liver enzyme elevations, and CBD dilatation as detected by abdominal ultrasonography 11 (Fig. 1 contains our previous management algorithm). Whereas MRC application resulted in accurate diagnosis of choledocholithiasis, we believed the approach was associated with overuse. Subsequently, we modified the approach to the management of patients with gallstone disease at our institution. The management approach categorized patients into four groups based on the level of suspicion for choledocholithiasis, which then directed patient evaluation and management. We hypothesized that with the implementation of these triage guidelines, there would be a reduction in redundant and unnecessary diagnostic testing, thus leading to improvements in magnetic resonance imaging and ERCP utilization. The utility of the new management guidelines was evaluated in this prospective nonrandomized study involving 440 patients.

Figure 1. Previous patient management algorithm: AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; MRC, magnetic resonance cholangiography; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopan-creatography.

METHODS

From January 1999 through April 2000, all patients who were candidates for laparoscopic management of cholelithiasis became eligible for preoperative evaluations directed by the new triage guidelines. Patients were evaluated and treated at the Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital, a public teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Texas-Houston Medical School. This facility primarily serves the medically indigent patients in the Houston metropolitan area. Initial patient evaluations consisted of history and physical examinations and serum analyses for bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, transaminase, and amylase. In addition, right upper quadrant abdominal sonograms were obtained for the determination of cholelithiasis and CBD diameter. On the basis of our previous observations, a CBD diameter of 5 mm as measured by abdominal ultrasonography was selected as the upper limit for the relatively young patient population with gallstone-related diseases treated at our institution. 11

Patient Selection and Treatment Algorithm

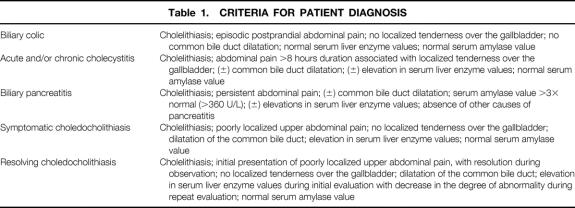

Patients were assigned to one of four groups. The assignment criteria included clinical diagnosis, abdominal ultrasonographic findings, and serum liver enzyme and amylase measurements. 11 Briefly, patients with cholelithiasis, a CBD diameter of 5 mm or more, and liver enzyme elevation, without clinical evidence of cholecystitis or biliary pancreatitis, were diagnosed with choledocholithiasis and triaged to group 1. Patients with cholelithiasis, CBD diameter of 5 mm or more, and liver enzyme elevation, in the presence of cholecystitis, biliary pancreatitis, or apparent resolving symptomatic choledocholithiasis were triaged to group 2. Patients with cholelithiasis, liver enzyme elevation, and a CBD less than 5 mm were triaged to group 3, and patients with cholelithiasis, a CBD less than 5 mm, and normal liver enzyme values were triaged to group 4.

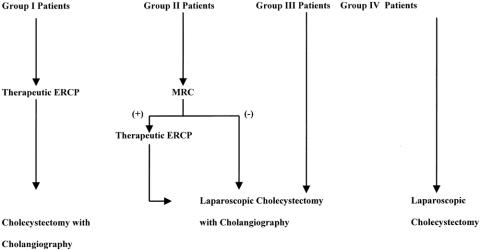

Patients with the highest level of suspicion for choledocholithiasis (group 1) underwent ERCP, endoscopic sphincterotomy, and endoscopic clearance of CBD stones before laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). Group 2 patients underwent further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging, and these patients underwent therapeutic ERCP when choledocholithiasis was demonstrated by MRC, whereas patients whose MRC did not detect choledocholithiasis underwent LC with intraoperative cholangiography (IOC). Patients with a moderate risk for choledocholithiasis (group 3) underwent LC and evaluation of the CBD with IOC at the time of surgery. Patients with a low suspicion for harboring CBD stones (group 4) underwent LC without IOC. Our current patient management algorithm is depicted in Figure 2. All inpatients were monitored daily before surgery with regard to changes in clinical examination findings and serum liver enzyme values. When significant changes in these parameters were noted, patients were reassigned to the appropriate group based on the new information. All patient assignments to the treatment groups were directly supervised by one of the general surgeons (T.H.L., D.W.M., K.L.K., E.K.P.) based on the diagnostic and assignment criteria listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Current patient management algorithm: MRC, magnetic resonance cholangiography; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 1. CRITERIA FOR PATIENT DIAGNOSIS

Table 2. SELECTION CRITERIA FOR PATIENT ASSIGNMENTS

AST, aspartate transaminase (normal range 12–45 U/L); ALT, alanine transaminase (normal range 0–55 U/L).

Total bilirubin normal range 0.1–1.2 mg/dL. Alkaline phosphatase normal range 37–107 U/L. Amylase normal range 34–122 U/L.

Eleven patients managed during the study period were excluded from the data analysis because of a management approach that deviated from the guidelines.

This study was conducted with the approval of the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas-Houston Medical School.

MRC Protocol

MRC was performed using either a torso or body coil, depending on abdominal girth, using the Horizon 1.5-T MRI system (General Electric). Traditional orthogonal axial and coronal and subsequently progressive oblique, axial, sagittal, and coronal MRC images were obtained utilizing the “single-shot,” 0.5 number of excitations (NEX) fast spin-echo technique, with a matrix of 512 × 512 with an echo time (TE) of 96.5 msec. Images were first obtained in the traditional orthogonal axial and coronal planes. Progressive oblique images were obtained in the following manner: sagittal oblique images were proscribed to the distal CBD based on a coronal long-TE (approximately 825 ms), thick slab scout image obtained using the “single-shot,” 0.5 NEX fast spin-echo technique. Coronal oblique images were proscribed to the distal CBD as seen on the sagittal oblique images. Axial oblique images were then proscribed to the distal CBD as seen on the coronal oblique images. The approximate length of time required for each study was 15 minutes.

Radiographic Film Interpretation

Ultrasonograms, MRC images, and IOC radiographs were interpreted by radiologists who were not informed of the patients’ treatment group assignments. The ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomies were performed by gastroenterologists who were not investigators involved with the current study. ERCP films were interpreted by radiologists unaware of the patients’ treatment group assignments.

Data Collection and End Points

All patients were triaged after the initial evaluation, and the data for groups 1, 2, and 3 were collected and recorded in a computer database concurrently. All patients received follow-up clinical evaluations during the initial 30-day period after cholecystectomy and then on an as-need basis for progress and complications related to missed CBD stones; routine serum chemistry measurements were not obtained during clinical follow-up. Missed common bile stones were defined as CBD stones that were unidentified by the designated patient triage process. The two principal end points of the study were the incidence of choledocholithiasis among patients in groups 1 through 4, and the incidence of missed CBD stones in each group. Additional end points included the frequency of MRC use and the requirement for application of both MRI and ERCP in a given patient.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean (± standard error) or percentages. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or two-tailed t test where appropriate. Results were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

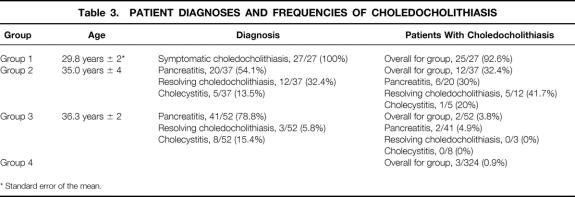

A total of 440 patients who underwent evaluation and treatment according to the triage guidelines were included in the data analysis. Three hundred eighty-one of the patients were female (86.6%) and 59 were male (13.4%). The patients ranged in age from 12 to 80 (mean 36.8). Twenty-seven of the patients were assigned to group 1 (6.1%), and all group 1 patients had the clinical diagnosis of symptomatic choledocholithiasis. Thirty-seven of the patients were assigned to group 2 (8.4%), with the most common diagnoses being acute pancreatitis, resolving choledocholithiasis, and cholecystitis. Fifty-two of the patients were assigned to group 3 (11.8%), with the most common diagnosis in this group being acute pancreatitis. Three hundred twenty-four patients were assigned to group 4 (73.7%), with majority of the patient evaluations performed in the outpatient setting, and the most common indications for cholecystectomy were biliary colic and cholecystitis. Table 3 shows the patient demographics and rate of choledocholithiasis. During the study period, 11 additional patients were eligible but excluded from our data analysis because of management approaches that deviated from the proposed guidelines.

Table 3. PATIENT DIAGNOSES AND FREQUENCIES OF CHOLEDOCHOLITHIASIS

* Standard error of the mean.

Group 1

All 27 group 1 patients underwent preoperative ERCP, and cholangiography was performed in 26 (96.3%). The average interval between abdominal ultrasonography and ERCP and between ERCP and LC was 4.0 ± 2.4 days and 2.1 ± 1.3 days, respectively. The failure to obtain an endoscopic cholangiography in one patient occurred because of a partially obstructing periampullary tumor, and this patient with cholangitis underwent a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography that drained the infected bile and identified multiple CBD stones. Twenty-five of the patients (92.6%) were identified with CBD stones and underwent therapeutic ERCP. Endoscopic clearance of the CBD was accomplished in 22 of these patients (88%), which was confirmed by IOC. Three patients had retained CBD stones after attempted endoscopic stone retrieval, and these patients underwent open CBD explorations at the time of their cholecystectomies. One patient who had undergone preoperative endoscopic retrieval of two stones had an additional CBD stone identified by IOC. After surgery, this patient underwent a second endoscopic procedure with successful CBD clearance.

Group 2

All 37 patients in group 2 underwent further evaluation with MRC; 12 patients (32.4%) had CBD stones identified. These patients underwent subsequent ERCP and CBD stones were identified in 11 of these patients; the remaining patient had sludge identified only. Endoscopic clearance of the CBD was successful in 10 of the 11 patients before cholecystectomy. The average interval between abdominal ultrasonography and MRC and between MRC and LC was 2.9 ± 1.6 days and 3.2 ± 1.6 days, respectively. Twenty-six of the group 2 patients had MRI studies that did not indicate the presence of CBD stones; these patients underwent LC with IOC. The IOC in one patient showed a 3-mm CBD stone that had not been identified by MRC; this patient underwent postoperative ERCP with successful stone retrieval. The IOC could not be completed in three of the group 2 patients because of technical difficulties (11.5%), and none of these patients had evidence of choledocholithiasis during the postoperative period.

Group 3

Fifty-two patients were assigned to group 3 and underwent LC, during which IOC was completed in 48 patients (90.6%). The average interval between the initial abdominal ultrasonography and surgery was 3.7 ± 2.4 days. Two patients (3.8%) had small CBD stones identified by IOC. One of these patients underwent laparoscopic CBD exploration, and the other patient underwent postoperative ERCP.

Group 4

Three hundred twenty-four patients were assigned to group 4, and 0.9% of the patients underwent IOC during LC for confirmation of biliary tract anatomy. Three patients (0.9%) had signs and symptoms suggestive of choledocholithiasis at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 6 months after surgery. Two of these patients underwent ERCP for the diagnosis and clearance of missed CBD stones, and the remaining patient presumably had spontaneous passage of a missed CBD stone before the negative postoperative ERCP.

Group Comparisons

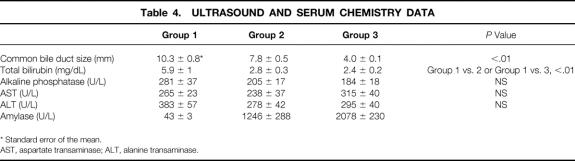

Common bile duct stones were identified in 1.3% of the patients with a CBD diameter of less than 5 mm (groups 3 and 4) and in 57.8% of patients with a CBD diameter of 5 mm or more (groups 1 and 2) (P < .001). Statistical differences were noted in the CBD diameter and total bilirubin value of group 1 patients compared with patients in groups 2 and 3. Ultrasonography and serum chemistry data are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. ULTRASOUND AND SERUM CHEMISTRY DATA

* Standard error of the mean.

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Overall, choledocholithiasis occurred in 43 patients (9.8%). The incidence of choledocholithiasis was 25 of 27 (92.6%) in group 1, 12 of 37 (32.4%) in group 2, 2 of 52 (3.8%) in group 3, and 3 of 324 (0.9%) in group 4 (P < .001). Missed CBD stones were identified in six patients (1.4%), with no occurrence in group 1 patients (0%), one patient in group 2 (2.7%), two patients in group 3 (3.8%), and three patients in group 4 (0.9%).

MRC and ERCP Results and Use

Thirty-nine patients (8.9%) underwent ERCP before LC; CBD stones were identified in 37 of these patients (94.9%). One of the two remaining patients had sludge identified during ERCP, and the other patient had a benign CBD stricture visualized. Thirty-two of the patients with choledocholithiasis (86.5%) had successful preoperative endoscopic clearance of the CBD, and the rest of the patients required CBD exploration or postoperative ERCP for stone extractions. Preoperative MRC was used in 37 patients (8.4%) during the study period. Twelve of these patients underwent subsequent ERCP for the extraction of CBD stones identified by MRI, resulting in the duplication of procedures in 2.7% of all patients (12/440) during the entire study period. One false-negative MRC result and one false-positive MRC result were encountered during the study period, thus resulting in an MRC accuracy rate of 94.6%.

Comparison With Previous Results

Compared with the group of patients managed at our institution before the implementation of the current management scheme, 11 the current triage process led to a significant reduction in MRC use (23.5% vs. 8.4%, P < .001). This was accomplished with the maintenance of a high rate of CBD stone identification during ERCP (94.9%) and a reduction in the frequency of redundant application of MRC and ERCP in any given patient (7% vs. 2.7%, P < .01). The rate of missed CBD stones was found to be unaffected by the implementation of the current guidelines (1.1% vs. 1.4%, P = .83).

DISCUSSION

Our data have important implications for physicians who care for patients with gallstone disease. Our findings suggest that patients can be accurately triaged into four groups based on relative suspicion for choledocholithiasis. The patient grouping can be subsequently used to direct patients toward the most appropriate diagnostic or therapeutic procedures: ERCP, MRC, LC with IOC, or LC without IOC.

Several previous studies have attempted to identify useful indicators for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis, and these have produced variable results. Difficulties in establishing reliable clinical predictors have led to several subsequent studies investigating the accuracy of noninvasive imaging modalities for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. 7–14 The current study differs in several respects from these prior investigations. Instead of comparing the diagnostic accuracy of the various imaging techniques, we adopted an approach that we believe would allow patients to be managed in a fashion that optimally uses the strengths of the available resources at our institution.

Choledocholithiasis is frequently associated with variable clinical presentations and spontaneous resolution. 15 Our patients who had an initial diagnosis of choledocholithiasis followed by subsequent resolution of the clinical picture were diagnosed with resolving choledocholithiasis. MRC evaluations revealed CBD stones in 41.7% (5/12) of the group 2 patients with this diagnosis. Based on our experience, accurate diagnosis in these patients without imaging studies was difficult; therefore, we found MRC to be useful in patient management. One of the problems we identified during the initial period of this study was difficulty in differentiating patients with symptomatic choledocholithiasis from those with cholecystitis. We believe this occurred because diagnosis was often based on subtle differences in the abdominal examination findings, and this differentiation had not been necessary before implementation of the current management approach. However, this problem quickly resolved with increased physician awareness and experience.

Acute biliary pancreatitis was the most common diagnosis among the group 2 and 3 patients. The incidence of choledocholithiasis has been shown to be low among patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, which presumably is due to the early passage of gallstones. 16,17 Early ERCP has not been shown to provide therapeutic benefits for patients without choledocholithiasis. 17 One of the questions raised regarding the management of patients with biliary pancreatitis involves the timing for the diagnosis and treatment of concurrent CBD stones. A single-center, randomized prospective study recently evaluated preoperative ERCP versus LC/IOC and postoperative ERCP for patients with confirmed CBD stones. 18 This trial, which included only patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, showed that 24% of the patients required ERCP when randomized to the postoperative treatment group. Several patients required remedial endoscopic procedures for CBD clearance, but no patient randomized to the postoperative treatment group required remedial surgery for retained CBD stones. Based on these results, the authors indicated a preference for the postoperative management of choledocholithiasis. The patients evaluated in that study had similar demographics to the group 2 patients in our study, where the incidence of choledocholithiasis was found to be 30% among our patients with pancreatitis. The success rate for complete resolution of choledocholithiasis by ERCP was 86.5% for the current group of patients, with the rate of success reported in the literature ranging from 75% to 92%. 6,18,19 The potential failure of ERCP has led us to believe that the routine treatment of choledocholithiasis during the postoperative period may lead to remedial surgery and added complications for some patients. Consequently, we believe that the use of preoperative MRC to identify choledocholithiasis among group 2 patients is appropriate.

The incidence of choledocholithiasis in group 3 patients was 3.8%, compared with the 0.9% seen in group 4 patients. Because these were not statistically different (P = .09), one can argue that routine IOC may be unnecessary for group 3 patients. Although we are intrigued by these results, we are concerned that the lack of significance may be due to inadequate group 3 sample size. Therefore, we have continued to evaluate the utility of IOC in these patients.

The statistical analysis revealed differences in the CBD size and serum total bilirubin values between the patient groups. Despite this observation, we did not find these factors to be clinically useful during the evaluation of individual patients. This was largely due to the wide variation in CBD size and serum bilirubin values that were noted among patients with and without choledocholithiasis. Therefore, we believe that a noninvasive imaging modality such as MRC was well utilized for the preoperative evaluation of our group 2 patients.

A nondilated CBD was found to be a reliable predictor of the absence of CBD stones in 98.7% of the patients during the current study. Five millimeters, defined as the upper limit of normal CBD size in the current study, was smaller than the 6 to 12 mm generally defined by other investigators. 3,20–27 The current standard was selected to accommodate the relatively young patients encountered at our institution, and the validity for this selection had been verified by our previous observations. 11 Whereas this measurement was found to be useful for the population of patients managed at our institution, larger CBD measurement standards may be needed when older patients are encountered.

There are several limitations to the current study; one of these is its prospective nonrandomized design, which requires comparison of current MRC use to previous use. Because the comparison group consisted of patients treated at our institution during the preceding 17 months, 11 we believe the difference in MRC use can be attributed to the intended changes in patient management and not to interval changes in patient demographics or other physician practices. The second potential limitation of this study is the lack of a formal cost analysis. This was not performed because we believe that a cost assessment would not reflect the true costs of patient management in our public hospital setting, where the length of hospital stay and the timing of MRC, ERCP, and surgery are frequently influenced by resource availability and other social factors. Another limitation is the relatively short follow-up period of our patients. By definition, retained CBD stones are stones that are identified within 2 years after cholecystectomy, 28 so the true frequency may be higher than reported. However, the relative frequency of late presentation of retained CBD stones should not differ significantly between the different treatment population; therefore, this underestimation should not alter the overall study conclusions.

In conclusion, the results of this prospective nonrandomized study suggest that initial triage of patients with cholelithiasis is important. Patient triage based on clinical assessment, routine serum chemistry analysis, and ultrasonographic determinations of CBD size results in the avoidance of unnecessary ERCP and an improvement in MRC utilization.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Terrence H. Liu, MD, Department of Surgery, Suite 30S 62 008, 5656 Kelley St., Houston, TX 77026-1967.

E-mail: terrence.h.liu@uth.tmc.edu

Accepted for publication December 18, 2000.

References

- 1.Diel AK. Epidemiology and natural history of gallstone disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1991; 20: 1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo KP, Traverso LW. Do predictive indicators predict the presence of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Am J Surg 1996; 171: 495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alponat A, Kum K, Rajnakova A, et al. Predictive factors for synchronous common bile duct stones in patients with choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trondsen E, Edwin B, Reiertsen O, et al. Prediction of common bile duct stones prior to cholecystectomy. A prospective validation of a discriminant analysis function. Arch Surg 1998; 133: 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul A, Milat B, Holthausen U, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Result of a consensus development conference. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 856–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamek HE, Albert J, Weitz M, et al. A prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with suspected bile duct obstruction. Gut 1998; 43: 680–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boraschi P, Neri E, Braccini G, et al. Choledocholithiasis: diagnostic accuracy of MR cholangiopancreatography. Three-year experience. Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 17: 1245–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varghese JC, Farrell MA, Courtney G, et al. A prospective comparison of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the evaluation of patients with suspected biliary tract disease. Clin Radiol 1999; 54: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto JA. Bile duct stones: diagnosis with MR cholangiography and helical CT. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI 1999; 20: 304–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu TH, Consorti ET, Kawashima A, et al. The efficacy of magnetic resonance cholangiography for the evaluation of patients with suspected choledocholithiasis before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 1999; 178: 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demartines N, Eisner L, Schnabel K, et al. Evaluation of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the management of bile duct stones. Arch Surg 2000; 135: 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majeed AW, Ross B, Johnson AG, Reed MW. Common duct diameter as an independent predictor of choledocholithiasis: is it useful? Clin Radiol 1999; 54: 170–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt DR, Reiter L, Scott AJ. Pre-operative ultrasound measurement of bile duct diameter: basis for selective cholangiography. Aust NZ J Surg 1990; 60: 189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anciaux ML, Pelletier G, Attali P, et al. Prospective study of clinical and biochemical features of symptomatic choledocholithiasis. Digest Dis Sci 1986; 31: 449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oria A, Alverez J, Chiappetta L, et al. Choledocholithiasis in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1991; 126: 566–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folsch U, Nitsche R, Ludtke R, et al. Early ERCP and papillotomy compared with conservative treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang L, Lo S, Stabile BE, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2000; 231: 82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes M, Sussman L, Cohen L, Lewis MP. Randomised trial of laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for common bile duct stones. Lancet 1998; 351: 159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacaine F, Corlette MB, Bismuth H. Preoperative evaluation of the risk of common bile duct stones. Arch Surg 1980; 115: 1114–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauer-Jensen M, Karesen R, Nygaard K, et al. Predictive ability of choledocholithiasis indicators. Ann Surg 1985; 202: 64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houdart R, Perniceni T, Darne B, et al. Predicting common bile duct lithiasis: determination and prospective validation of a model predicting low risk. Am J Surg 1995; 170: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltzstein EC, Peacock JB, Thomas MD. Preoperative bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and amylase levels as predictors of common bile duct stones. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1982; 154: 381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkun AN, Barkun JS, Fried GM, et al. Useful predictors of bile duct stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delsanto P, Kazarian KK, Rogers JF, et al. Prediction of operative cholangiography in patients undergoing elective cholecystectomy with routine liver function chemistries. Surgery 1985; 98: 7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr LL, Frame BC, Coulanjon A. Proposed criteria for preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in candidates for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 1999; 13: 778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham SM, Flower JL, Scott TR, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and common bile duct stones. The utility of planned perioperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and sphincterotomy: experience with 63 patients. Ann Surg 1993; 218: 61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nahrwold DL. Retained common duct stones. In: Cameron JL, ed. Current surgical therapy. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book, Inc; 1989: 349–351.