Abstract

Objective

To present the first new information in the past 25 years concerning the life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted. This paper reports on recently discovered personal correspondence of Dr. Halsted, beginning at age 66, to a young lady, Elizabeth Blanchard Randall, 40 years his junior.

Summary Background Data

Dr. William Stewart Halsted is generally considered the most important and influential surgeon that this country has produced. During his Hopkins days in Baltimore (1886–1922) he was rather reclusive, and little is known of his personal life. He was married but had no children. Several biographies written by Halsted’s contemporaries constitute the bulk of what is known about Halsted’s personal life.

Methods

All extant letters from Dr. Halsted to Miss Randall were reviewed. Archival materials were consulted to understand the context for this friendship. The correspondence between Halsted and Randall took place during a 3-year period, although their acquaintance was probably long-standing.

Results

The letters reveal Dr. Halsted and Miss Randall’s great and warm affection for each other, despite their 40-year age difference. The letters have a playful nature absent in Halsted’s other correspondence. This relationship has not been previously noted.

Conclusions

Late in Halsted’s life, he developed a warm and affectionate relationship with a young lady 40 years his junior, as revealed in Halsted’s correspondence. Halsted’s warm, personal, and playful letters are in stark contrast to his biographers’ portrayals of him as a more serious and reclusive person.

A small collection of letters from William Stewart Halsted to Elizabeth Blanchard Randall was recently found in the family papers of Harry R. Slack Jr. and his wife, the former Elizabeth Blanchard Randall. (The Slack family papers are located in the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.) There are ten letters, eight of which are dated, and one telegram. The dated correspondence took place from November 1918 to September 1921; the correspondence began when Halsted was 66 years old and Miss Randall was 26. The affectionate and playful nature of Dr. Halsted’s letters suggests that he and Miss Randall shared a very fond attachment to each other.

CAREER AND CHARACTER OF DR. HALSTED

Dr. William Stewart Halsted had a remarkable life. 1 Born into privileged circumstances in New York City, he was reared in a comfortable home on Fifth Avenue. He attended preparatory school at the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and spent his college years at Yale University. Returning to New York City for medical school, he enrolled in the College of Physicians and Surgeons. In college he was only an average student and was interested primarily in athletics and social activities. At medical school, however, he excelled and graduated near the top of his class. After 1 year at Bellevue as an intern and a second year at New York Hospital as a house pupil, Halsted traveled abroad and spent 2 years (1878–1880) meeting and observing the most highly regarded surgeons in Europe.

Halsted returned to New York City in 1880 and began his surgical career. He was very active surgically, was on the staffs of several hospitals, wrote many papers, and enjoyed a very full and active social life. He shared a home on 25th Street between Madison and Fourth Avenues with a close internist friend of his, Dr. William McBride, and several evenings a week the two of them entertained friends and colleagues at their home. Halsted soon gained a reputation as a charismatic and inspiring teacher and an indefatigable surgeon. He was described as “full of enthusiasm and the joy of life.”2 One of his greatest contributions, the introduction of local and regional anesthesia, emanated from this era. Unfortunately, during his experiments with cocaine, he became addicted and as a consequence spent most of 1886 and 1887 at Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, under treatment for his addiction. 3

Halsted moved to Baltimore in 1886 after his first admission to Butler Hospital to join Dr. William H. Welch, his devoted friend and mentor. Welch had been recruited to Baltimore to hire faculty for the Johns Hopkins Hospital, which was to open in 1889, and the new Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, which opened later in 1893. Halsted lived with Welch and worked in his research laboratory. In 1887 he was readmitted to Butler Hospital. Subsequently he returned to Baltimore, and in 1890, 1 year after the hospital opened, he was appointed chief of surgery of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and in 1892 he was appointed professor of surgery in the University. While at Hopkins Halsted had a brilliant career, becoming one of America’s most productive and influential surgeons.

After his move to Baltimore, Halsted’s personality underwent a dramatic change. Whereas he had been outgoing and gregarious as a young man in New York, colleagues in Baltimore described him as reticent, shy, reclusive, and overly fastidious, conscientious, and contemplative. His good friend and biographer Dr. William MacCallum, Welch’s successor as chief of pathology at Hopkins, described him as “an elusive personality, so hidden in his habitual reserve and so hedged round with the formality of his manner that few knew him well.”2 One of his most outstanding students, and a great admirer, Dr. George W. Heuer, described Halsted as follows: “he was intimate with few and his habits at work precluded frequent contacts with his colleagues. . .his own shyness made it difficult for him to participate easily in the friendly, laughing intercourse of a large group. . .he avoided people, very often deliberately. . .in relation with his colleagues he seemed a lonely figure.”4

Halsted had numerous acquaintances in Baltimore but few close friends. His personality change and subsequent reticence were probably due in part to his continuing drug addiction. To conceal his dependency, he, perhaps, avoided close contact with people. Yet Welch remained a steadfast friend and confidante of Halsted throughout his career. Welch was one of the few individuals who knew of Halsted’s persistent struggle with addiction. William Osler, Halsted’s physician, was also aware of his problem.

Halsted had few intimate friendships with men, but his associations with women were even more limited. MacCallum described women’s views of Halsted as follows: “they saw him a man evidently of great intellectual power, courtly and polite in the extreme, always a little distant and not to be treated with familiarity, a man not accustomed to triumphant success with women, but on the contrary shy and, with them, a little ill at ease.”2

Shortly after Halsted’s appointment as director of surgery of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, he ended his long bachelorhood. On June 4, 1890, Halsted married Miss Caroline Hampton; he was 38 and she was 29. He met Miss Hampton when she worked as his scrub nurse at Hopkins. Having trained at New York Hospital, Miss Hampton came to Baltimore in 1889 to work in the operating rooms at Hopkins. There she earned high regard for her excellent nursing skills.

Halsted and Miss Hampton both came from aristocratic backgrounds. Whereas he was from an elite and prosperous Northern family, she was from a very distinguished Southern family whose fortunes were diminished in the Civil War. Her paternal uncle was the legendary General Wade Hampton. Because of the long-standing social eminence of their families, they may not have felt the need to pursue a place in Baltimore society. For whatever reason, they did not conform to the usual social conventions. Seldom did they entertain or attend social events, and as a couple they were remote and aloof. Their happiest times together seem to have been the visits they shared at High Hampton, their family retreat in North Carolina. At High Hampton Caroline immersed herself in gardening, riding, and tending to farm animals and crops. Halsted also savored the pleasures of country life; he took particular pride in cultivating dahlias. There were often times in their marriage when they were apart for long periods. Halsted went alone to Europe for extended visits, and Caroline spent months at a time in North Carolina without Halsted. As enigmatic as their marriage may have appeared to their families and friends, they seem to have been devoted to each other. They never had children, so no direct descendants survive.

The biographies of Halsted by William MacCallum 2 and Samuel Crowe 5 were written largely from the personal recollections of the authors. There are few recollections by others because Halsted had such a limited circle of close friends. Moreover, he did not keep a personal diary, and the correspondence he left behind is largely of a formal nature. Thus, little is known about his personal life.

ELIZABETH BLANCHARD RANDALL

Elizabeth Blanchard Randall was born in Baltimore in 1892. Her father, Blanchard Randall, was a prominent Baltimore lawyer who served on the Board of Trustees of the Johns Hopkins University form 1902 to 1942. Elizabeth was one of four daughters. She attended St. Timothy’s School, an exclusive private girl’s school in the Baltimore area, and later enrolled in courses at the Johns Hopkins University. She was known primarily for her social welfare endeavors. In 1916 she served as manager and secretary of the Electric Sewing Machine Society, a group that trained women to be self-sufficient. Her main interest was in working with physically handicapped patients. She volunteered as an occupational therapist at the Johns Hopkins Hospital and during World War I served with the Red Cross as a reconstruction aide, stationed at bases in Rahway and Colonia, New Jersey. In June 1922 she married Dr. Harry R. Slack Jr., an otolaryngologist who had trained under Dr. Samuel Crowe at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. After her marriage and the birth of her three children, she settled into family life and continued to play a significant role in community service and Baltimore society. Elizabeth Randall Slack was a member of various prestigious social clubs, including the Hamilton Street Club, the Mt. Vernon Club, and the Gibson Island Club. In addition, she was a member of the Women’s Board of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Colonial Dames of America, and the Maryland Historical Society. She served on the Board of Trustees of St. John’s College in Annapolis, the Board of the Lyric Opera Theater in Baltimore, and the Board of the Baltimore Museum of Art. She subsequently was President of the Junior League and the Society for Preservation of Maryland Antiquities. She died in January 1983 at age 91.

THE LETTERS

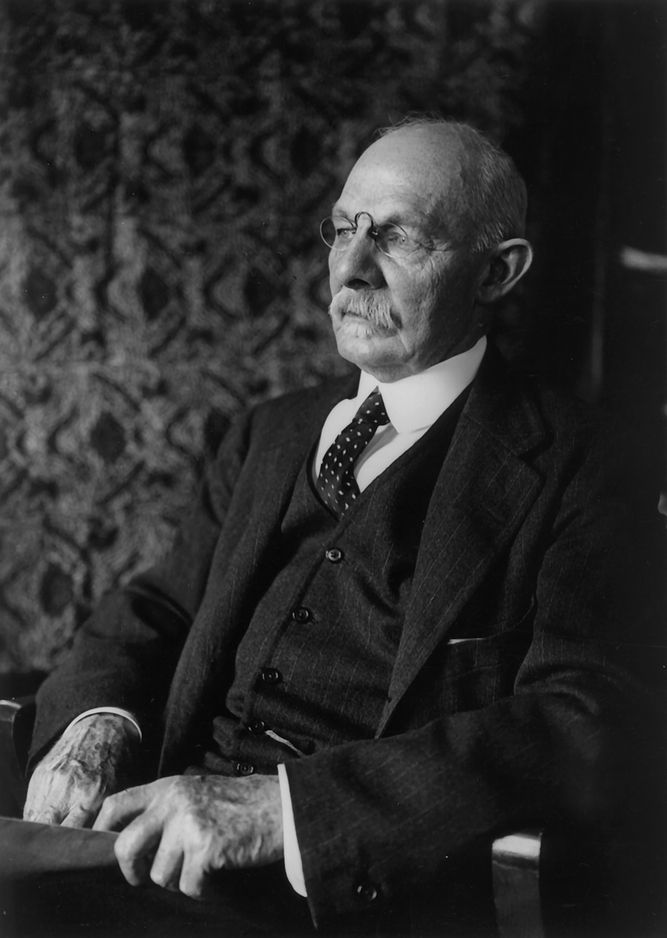

In 1987, W. Cameron Slack, son of Elizabeth Randall Slack, donated a collection of family papers to the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. When the papers were processed in 1997, a series of letters from William Halsted to Elizabeth Randall were discovered. Halsted wrote these letters to Elizabeth Randall before her marriage. They were written during a period of 3 years, from November 1918 to September 1921. There are ten letters and one telegram. When the correspondence began, Halsted was 66 and Elizabeth Randall was 26, a 40-year difference in age (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. William S. Halsted by John Stocksdale, 1922, black and white photograph. The William S. Halsted Collection, The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Figure 2. Elizabeth Blanchard Randall by unknown photographer, 1917, black and white photograph. The Randall and Slack Family Collection, The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

The style of the letters from Halsted to Miss Randall is in stark contrast to the stiff formality of his professional correspondence. Halsted writes to her with great warmth, affection, and playfulness. Because the letters from Miss Randall to Halsted have apparently not survived, the full significance of their joint correspondence cannot be easily understood. Nevertheless, Halsted’s letters offer a glimpse into a lighter and more romantic aspect of his character. Usually dour and withdrawn, he sparkled with delicate wit and winsome charm in his letters to Miss Randall. Even though Miss Randall’s side of the correspondence has not been found, Halsted’s letters written in response to notes and gifts from her suggest that she too had great fondness for him, although her courtship with Harry Slack occurred during the later period of her correspondence with Halsted.

Following are excerpts from seven of the letters; the entire telegram is included.

The first dated letter in the series from Halsted to Miss Randall was written November 2, 1918. Excerpts follow:

My Dear Miss Bessie,

I am charmed by your letter which even in its expurgated form is much too “lurid” for my deserving, but not “für mein Fahigkeit,” respective “geraümigkeit zu verschlucken” which, as young ladies so well know, is infinite in old men.

Wonderfully distressed to hear of the “malade” and the boiling oil and fearing that you may succumb before Christmas I am sending the enclosed card and nervously scanning the obituary notice columns...

Faithfully yours,

William Halsted

This initial letter addresses her in a familiar style, unlike the more formal salutations of his professional correspondence. This letter is clearly in response to a letter from Miss Randall that must have contained some flattering remarks to which he is responding. The second portion of the letter concerning comments about “malade” is difficult to interpret. “Wonderfully distressed” may be setting a humorous tone, and using the French “malade,” connoting illness or convalescence, it appears as if Halsted is gently chiding her regarding a real or perceived condition or illness. The reference to “boiling oil,” a popular wound treatment in the premodern surgical era, does little to illuminate the intent of this correspondence, but regardless, this is clearly a playful, personal letter.

Halsted wrote the next letter approximately 3 weeks later (November 22, 1918). Excerpts follow:

Verily only a highly trained psychiatrist could have derived from such meager data that copious tears were flowing on the corner of Eutaw Place and Dolphin Street.

I wish that you might know how highly prized is each stitch of the dainty Christmas gift, the pockets of which shall harbor only the handkerchiefs reserved for the special occasions on which the recipient indulges in thoughts of a precious little lady in France.

This letter seems to be written in response to a Christmas gift that Miss Randall had sent to Halsted. She apparently was in New York City anticipating being sent to France by the Red Cross. Instead, she eventually was stationed in New Jersey.

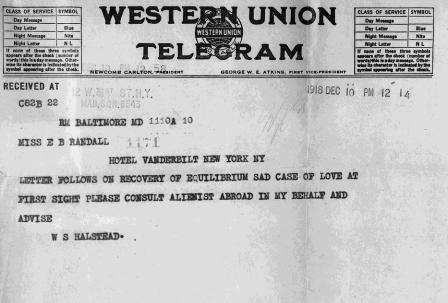

Approximately 2 weeks later (December 10, 1918), Dr. Halsted sent the following telegram to Miss Randall at the Hotel Vanderbilt in New York City (Fig. 3):

Figure 3. Dr. Halsted sent this telegram to Miss Randall as she awaited departure to join the Johns Hopkins Base Hospital 18 in France. However, she never set sail because the Hopkins Base Hospital received orders to return to the United States on December 21, 1918. The Randall and Slack Family Collection, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

LETTER FOLLOWS ON RECOVERY OF EQUILIBRIUM SAD CASE OF LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT PLEASE CONSULT ALIENIST ABROAD IN MY BEHALF AND ADVISE W.S. HALSTEAD [sic]

The telegram seems to have been sent in response to receiving something from Miss Randall. Did she give him a photograph or a special memento? At that time the term “alienist” was used for psychiatrist. Is he asking her in jest to consult a psychiatrist on his behalf to give him advice?

The next letter in the sequence is written from Dr. Halsted to Miss Randall about 9 months later (Sept. 11, 1919). This letter is perhaps in response to a letter from her announcing that she is returning from Red Cross duty in New Jersey. An excerpt follows:

I wish that you might know the pleasure your precious little billet-doux gave or is giving me. The invitations to drive are all eagerly accepted, so please secure from Mr. Randall promises to chaperone us.

He thanked her for her billet-doux (love letter) and the various invitations that she has apparently extended in her letter. Presumably she was returning to Baltimore from New Jersey and had suggested that the two of them go on some outings. Although Halsted “eagerly” accepted her “invitations,” he followed the normal social convention and asked that her father chaperone them.

The next letter (May 22, 1921) indicated that their fondness for each other had not diminished. Excerpts follow:

I am so distressed to learn that you have succumbed to the Ziegenpeter. . .Remember our engagement to see the Carpentier-Dempsey dispute in Hoboken, July 2nd, and think only of the surgeons. . .P.S. I trust that “der schwarzer Diener” conveyed to you my invitation to luncheon tomorrow at the Country Club to meet my sister, Mrs. Terry.

Apparently there were plans for Halsted to accompany Miss Randall to New Jersey to attend the Carpentier-Dempsey world heavyweight prize fight. This would have been a most unusual rendezvous for a distinguished older man and a socially prominent young woman. He also mentions that they are to have lunch the next day at the Country Club so that she can meet his sister, Mrs. Terry, indicating the measure of respect he had for his young friend.

Approximately 2 months later, the prize fight had taken place. Halsted did not attend, perhaps because of illness, but Miss Randall did. She wrote to him about the event, and Dr. Halsted thanked her for her letter. The prose and tone of this letter (July 12, 1921) are quite unlike the style of his extensive correspondence with others. Excerpts follow:

So you really evented? Oh the deadly girls—bloodthirsty too perhaps! I am truly thrilled at the thought of you braving the heat and mosquitoes of Jersey City in order to witness the process of jellification of Carpentier’s countenance. . .it was very charming of you to write me such a long and lurid description of the slaughter.

The final dated letter from Dr. Halsted to Miss Randall was written September 12, 1921. Halsted was in High Hampton, in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he spent part of each summer. He is responding to a letter from Miss Randall. He remains, almost 3 years after writing his first letter to her, obviously very affected by this young woman. He describes his reaction to her letter in the excerpts that follow:

I carry it about with me everywhere—on fishing excursions, on mountain trails, on raids of moonlight stills through “panthertown,” to Sunday school and the dahlia garden. I wonder if the Paris creations in which you are presumably soaring can be so becoming and entrancingly lovely as the pink costume you wore the afternoon you so graciously entertained my friends, the Leriches from Lyon, and my adored assistant G.J.H.—if he leaves us I shall be desolated and altogether inconsolable except in the delicious and fleeting moments of Cloud-Capped.

Halsted obviously remains very fond of Miss Randall, and this letter appears to have meant a great deal to him. He also makes reference to a time when she apparently hosted a social event for him when Dr. Henri Leriche, the renowned surgeon, was visiting from Lyon, France. “G.J.H.” refers to Dr. George J. Heuer, who at that time was trying to decide whether to go to the University of Cincinnati as the chief of surgery. Cloud-Capped was the name of the Randall family home in Catonsville, Maryland.

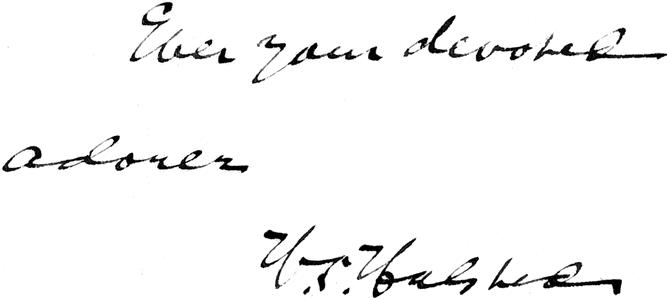

The most passionate of all the ten letters that Halsted sent Miss Randall is undated (Fig. 4). It is full of rapture and fanciful imagery. Halsted writes as a man who has a deep emotional attachment:

Figure 4. The closing of the undated letter from Dr. Halsted to Miss Randall that is cited above. The Randall and Slack Family Collection, The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Please picture me every morning at eight o’clock, unchaperoned, awaiting your arrival and prepared, flinging consequences to the winds, to float southwards on and on, sipping sponge cakes and breathing inarticulate words into the interstices of the ‘bean catchers,’ between sips.

Ever your devoted adorer

CONJECTURE AND CONCLUSION

The series of letters from William Stewart Halsted to Elizabeth Blanchard Randall took place during a period of nearly 3 years. The first letter indicates that they were well acquainted and had probably known each other for some time. Halsted died 1 year after the last dated letter to Miss Randall, but one can presume that they probably saw each other during that final year. Halsted may well have had other close relationships with both women and men, but because he was secretive and reclusive, these never came to light. It seems likely that if colleagues and friends such as Welch, MacCallum, and Osler had known of such relationships, they would have commented on them after Halsted’s death. MacCallum, in his biography of Halsted, describes his letter-writing style as follows: “At best he was not a gifted letter writer; his letters are very courteous, rather excessively polite, and always a little stilted and formal, without any abandon or play of imagination.”2 The letters that Halsted wrote to Miss Randall are in stark contrast to that description. Because of the scarcity of surviving information, the true nature of their relationship may never be known. From these ten letters and one telegram written by Halsted, we can assume that he and Miss Randall shared a great and warm affection for each other. This small collection of correspondence constitutes yet another enigma in the life of William Stewart Halsted (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Calling card and envelope found in the undated letter cited on page 11. Montage and scan by Marjorie W. Winslow.

Footnotes

Correspondence: John L. Cameron, MD, 720 Rutland Ave., Ross 759, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Accepted for publication December 22, 2000.

References

- 1.Cameron JL. William Stewart Halsted: our surgical heritage. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacCallum WG. William Stewart Halsted: surgeon. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press; 1930.

- 3.Nunn DB. William Stewart Halsted: transitional years. Surgery 1951; 121: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heuer GW. Dr. Halsted. Bulletin Johns Hopkins Hospital 1952 (supp); 90:2. [PubMed]

- 5.Crowe SJ. Halsted of Johns Hopkins. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1957.