Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of bile duct injury (BDI) sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy on physical and mental quality of life (QOL).

Summary Background Data

The incidence of BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy has decreased but remains as high as 1.4%. Data on the long-term outcome of treatment in these patients are scarce, and QOL after BDI is unknown.

Methods

One hundred six consecutive patients (75 women, median age 44 ± 14 years) were referred between 1990 and 1996 for treatment of BDI sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Outcome was evaluated according to the type of treatment used (endoscopic or surgical) and the type of injury. Objective outcome (interventions, hospital admissions, laboratory data) was evaluated, a questionnaire was filled out, and a QOL survey was performed (using the SF-36). Risk factors for a worse outcome were calculated.

Results

Median follow-up time was 70 months (range 37–110). The objective outcome of endoscopic treatment (n = 69) was excellent (94%). The result of surgical treatment (n = 31) depended on the timing of reconstruction (overall success 84%; in case of delayed hepaticojejunostomy 94%). Five patients underwent interventional radiology with a good outcome. Despite this excellent objective outcome, QOL appeared to be both physically and mentally reduced compared with controls (P < .05) and was not dependent on the type of treatment used or the severity of the injury. The duration of the treatment was independently prognostic for a worse mental QOL.

Conclusions

Despite the excellent functional outcome after repair, the occurrence of a BDI has a great impact on the patient’s physical and mental QOL, even at long-term follow-up.

Since its introduction in the late 1980s, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstone disease. Today more than 75% of cholecystectomies are performed laparoscopically. 1,2 Important advantages over the classical open procedure are a decreased rate of overall complications, a better cosmetic result, faster postoperative recovery, and a shorter hospital stay. A randomized trial has shown that LC can be performed safely as same-day surgery. 3 The main concern is the higher incidence of bile duct injury (BDI); despite many studies on the mechanism of injury and the value of preventive measures such as intraoperative cholangiography, the rate of BDI remains as high as 1.4%. 1,2,4–6

Earlier studies recognized that the management of BDI may be troublesome and should be performed in a specialized center. 1 Depending on the type of injury, treatment is surgical or endoscopic. Reports from these specialized centers, as recently summarized in an analysis of 40 series from the United States, show a favorable short-term technical outcome, but only a few series provide information on long-term outcome. 7 No data are available on the quality of life (QOL) of patients treated for BDI after intended LC. During regular follow-up at outpatient visits of patients who had been treated for BDI at our institution, we noticed a high prevalence of undefined abdominal complaints, whereas remarkably few patients had symptoms of recurrent jaundice or cholangitis. Also, many patients believed their complaints had not been taken seriously at the time of their first symptoms, leading to a delay in diagnosis of the injury, and were disappointed by the reluctance of the primary surgeon to admit the procedural error. About 10% of the patients were still involved in lawsuits. Previous studies on malpractice litigation after LC already showed the impact of these aspects on trial verdicts and liability payments. 8,9 We expected that these circumstances would affect the overall QOL. Therefore, we conducted a study to evaluate the long-term QOL in 106 patients treated for BDI sustained during LC in relation to the objective functional outcome of treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

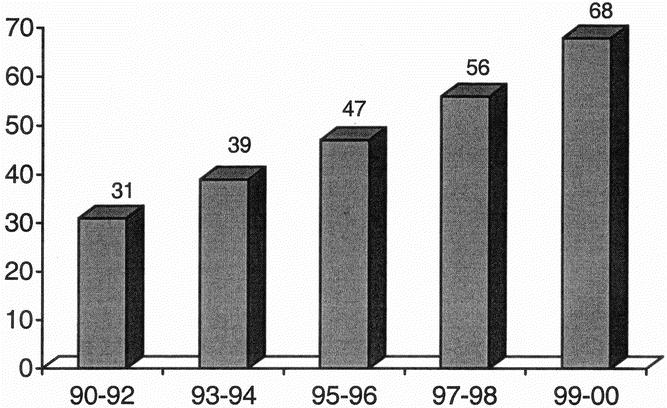

During the past 10 years, 241 patients with BDI after intended LC were referred from 45 different hospitals in The Netherlands for diagnostic workup, treatment, or both. There was a slight increase in the number of referrals over the years (Fig. 1). Most patients (n = 143) were treated endoscopically; 71 patients required surgical intervention, mainly consisting of reconstruction of the biliary tree; and 16 patients were treated by radiologic dilatation, usually of a previously created biliodigestive anastomosis. In 11 patients, only diagnostic procedures were performed to assess the extent of the injury, and recommended treatment was performed in the referring hospital.

Figure 1. Number of patients referred for diagnosis and/or treatment of bile duct injury sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

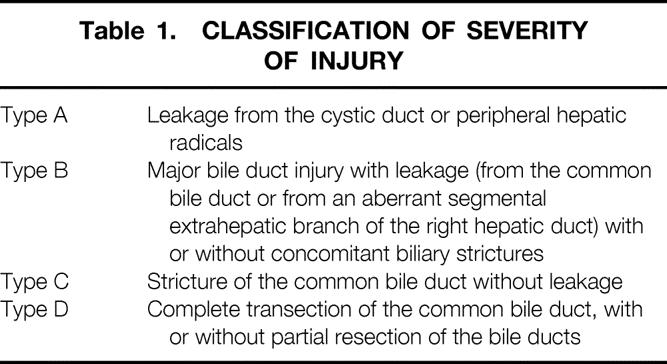

The severity of the injury was classified according to the Amsterdam criteria (Table 1):11 a type A lesion was defined as leakage from the cystic duct or peripheral hepatic radicals (n = 71); a type B lesion was a major BDI with leakage (from the common bile duct [CBD] or from an aberrant segmental extrahepatic branch of the right hepatic duct) with or without concomitant biliary strictures (n = 46); a type C lesion was a stricture of the CBD without leakage (n = 48); and a type D lesion represented a complete transection of the CBD, with or without partial resection of the bile ducts (n = 76).

Table 1. CLASSIFICATION OF SEVERITY OF INJURY

In this study, the first 106 patients (diagnosed between June 1990 and November 1996) were followed up after the intended definitive treatment with long-term QOL as the focus of the study. The classification of injuries and the effect of early detection have been reported previously. 10 The prevalence of the different types of injury in these 106 patients was comparable with the prevalence in the larger group of 241 patients.

The long-term patient outcome was analyzed according to the type of treatment given after referral (i.e., endoscopic, surgical, or both) and according to the type of BDI. Objective outcome (interventions, hospital admissions, and laboratory data during follow-up) was assessed by reviewing the data collected at the regular outpatient visits. In a personal questionnaire, patients were asked whether they had undergone additional treatment in other hospitals, and if so, the hospitals and general practitioners were contacted to obtain information. Liver function tests were also performed.

Quality of life was assessed by sending all patients the MOS Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire. 12 The SF-36 health questionnaire consists of eight subscales: Physical Functioning, Role Functioning, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Role–Emotional, and Mental Health. On the basis of these subscales, component summary scores can be calculated to provide a global measure of physical and mental functioning, respectively. 13 The Physical Component Summary (PCS) consists of the subscales Physical Functioning, Role Functioning, Bodily Pain, and General Health; the Mental Component Summary (MCS) comprises the subscales Vitality, Social Functioning, Role–Emotional, and Mental Health. QOL scores of patients with BDI were compared with scores of healthy age- and sex-matched Dutch controls, and of patients who had undergone uncomplicated LC, derived from an ongoing study among patients undergoing elective cholecystectomy. 14 In that study, the Short Form General Health Survey (SF-20) 15 was used, supplemented by the four items of the Vitality scale as used in the SF-36, resulting in the SF-24. Aside from the subscale Emotional Role Functioning, both the SF-36 and the SF-24 encompass the same dimensions and thus are comparable in content, albeit not entirely identical.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Comparison between groups was done using chi-square testing, with the Fisher exact test and the Mann-Whitney test when appropriate. The impact of patient characteristics and perioperative factors on QOL was univariately analyzed using the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney test. Alleged risk factors were age, sex, comorbidity hindering daily activities (i.e., American Society of Anesthisiologists score 3), delay in the diagnosis of the injury, type of injury, type of treatment (endoscopic or surgical), duration of treatment, and length of the intervention-free interval (i.e., time between the last contact with the general practitioner or a specialist for any abdominal symptoms, and follow-up). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess any difference between the different types of injuries and between the different types of treatment modalities. All risk factors associated with impaired QOL with a P < .3 on univariate analysis were entered into a multiple linear regression model, with a forward selection strategy, to calculate their independent prognostic value. The prognostic values of the individual variables after multiple logistic regression analysis are expressed with their probability value, the regression coefficient, and the 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

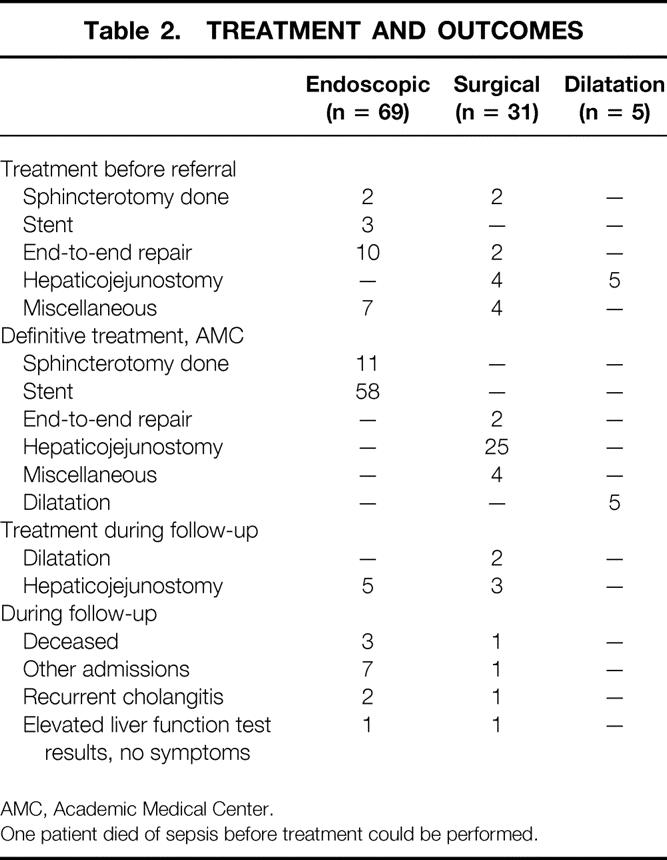

Of the 106 patients in this study, 31 were men and 75 were women, with a mean age of 44 ± 14 years. Before referral, a third of the patients had been treated elsewhere (n = 39): 7 patients had undergone endoscopic treatment, in 12 patients a primary end-to-end repair of the CBD had been performed, and 9 patients had undergone hepaticojejunostomy before referral (Table 2). Further, percutaneous drainage had been performed in six patients, relaparotomy and primary suturing of the leak in three patients, and laparoscopic drainage in two patients. After referral to our institution, the BDI was treated endoscopically in 69 patients, surgically in 32 patients, and radiologically in 5 patients. Median follow-up after treatment was 70 months (range 37–110). Liver function tests were performed during follow-up in 80% of the patients, up until 44 to 58 months after LC.

Table 2. TREATMENT AND OUTCOMES

AMC, Academic Medical Center.

One patient died of sepsis before treatment could be performed.

Endoscopic Treatment

Endoscopic treatment was performed in 69 patients. One patient (type A) died 5 days after sphincterotomy as a result of myocardial infarction; no signs of bleeding were found. Eleven patients underwent sphincterotomy and 58 patients underwent stenting of the CBD. During follow-up, hepaticojejunostomy was performed for persistent biliary stenosis despite 1 year of stenting in five patients (7%). Thus, endoscopic treatment sufficed in 93%. During follow-up, three patients died of unrelated causes. Seven patients were admitted once to another hospital: one patient was conservatively treated for an ileus and six patients were observed for undefined abdominal complaints. Two patients still had recurrent attacks of cholangitis at the time of follow-up; one patient had persistent mildly elevated liver function test results without symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

One patient died of sepsis before reconstruction could be performed. Twenty-five patients underwent hepaticojejunostomy after referral. During follow-up, 4 of 25 patients required percutaneous dilatation for anastomotic stricture (16%). Three of these four patients had undergone early reconstruction (within 6 weeks after LC), which is no longer recommended, and only one patient who had undergone delayed hepaticojejunostomy required revision of the anastomosis (6%). In the fifth patient who required hepaticojejunostomy during follow-up, an anastomotic stricture had developed after a primary surgical repair with T-tube drainage.

During follow-up, one patient died of recurrent gallbladder carcinoma 30 months after LC. One patient had been admitted once to an outside hospital for undefined abdominal complaints, and one patient still had recurrent attacks of cholangitis at the time of follow-up. One patient had persistent mildly elevated liver function test results without symptoms.

Percutaneous Dilatation

Five patients were referred to our institution for percutaneous dilatation after development of an anastomotic stricture, after hepaticojejunostomy performed elsewhere. Three of these patients had undergone reconstruction within 6 weeks after the injury, and two patients had undergone immediate conversion and subsequent reconstruction. Dilatation was successful in all five patients (i.e., no cholestasis or cholangitis attacks occurred during follow-up).

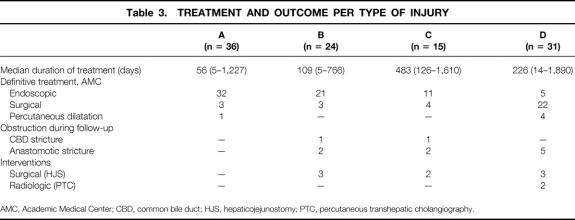

Outcome Per Type of Injury

Treatment per type of injury is summarized in Table 3. The functional outcome of treatment for BDI appeared the same, irrespective of the severity of the injury. The duration of the treatment (i.e., the period between the time of diagnosis and the end of treatment was significantly longer in type C lesions versus type A and B lesions (P < .05). The time between the first and the last stent may be long, but stent exchanges were mainly done as outpatient procedures. As previously reported, the diagnosis delay was significantly longer for type C lesions than for the other lesions. 10 During follow-up, three patients with type B lesions and two patients with type C lesions underwent hepaticojejunostomy. In five patients with type D lesions, an anastomotic stricture developed; four of these patients had initially undergone early hepaticojejunostomy.

Table 3. TREATMENT AND OUTCOME PER TYPE OF INJURY

AMC, Academic Medical Center; CBD, common bile duct; HJS, hepaticojejunostomy; PTC, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

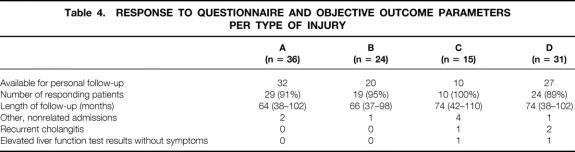

Long-Term Quality of Life

Of 106 patients, 11 were lost to follow-up and 6 had died, as described above. Of the remaining 89 patients, 82 returned the questionnaire (response rate 92%) (Table 4). Aside from regular outpatient visits, which all patients attended, personal follow-up was obtained a median of 70 months (range 37–110) after LC and 63 months (range 10–94) since the last contact with the general practitioner or a specialist for any abdominal symptoms (the intervention-free interval).

Table 4. RESPONSE TO QUESTIONNAIRE AND OBJECTIVE OUTCOME PARAMETERS PER TYPE OF INJURY

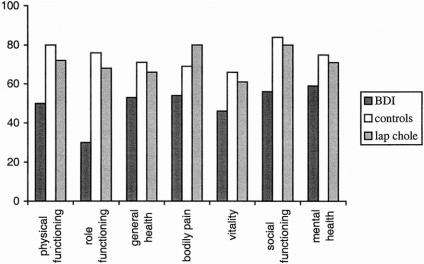

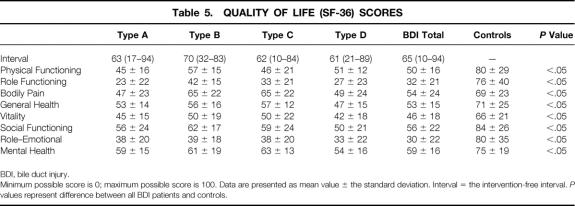

QOL in patients who had been treated for BDI was significantly impaired on all eight subscales. Compared with patients who had undergone an uncomplicated LC, 14 and compared with healthy age- and sex-matched controls, the difference was significant (P < .05) on all subscales (Fig. 2). QOL was not different for patients treated endoscopically or surgically (Table 5).

Figure 2. Quality of life of 82 patients who have been treated for BDI, compared with quality of life in healthy, matched controls (P < .05) and in patients 2 years after uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy (P < .05).

Table 5. QUALITY OF LIFE (SF-36) SCORES

BDI, bile duct injury.

Minimum possible score is 0; maximum possible score is 100. Data are presented as mean value ± the standard deviation. Interval = the intervention-free interval. P values represent difference between all BDI patients and controls.

Comparison of the different types of injuries showed that patients with a type A lesion, presumably minor injuries, had a comparably poor QOL compared with patients with a type D lesion (a major lesion that required immediate treatment by drainage procedures and long-term surgical treatment by reconstruction).

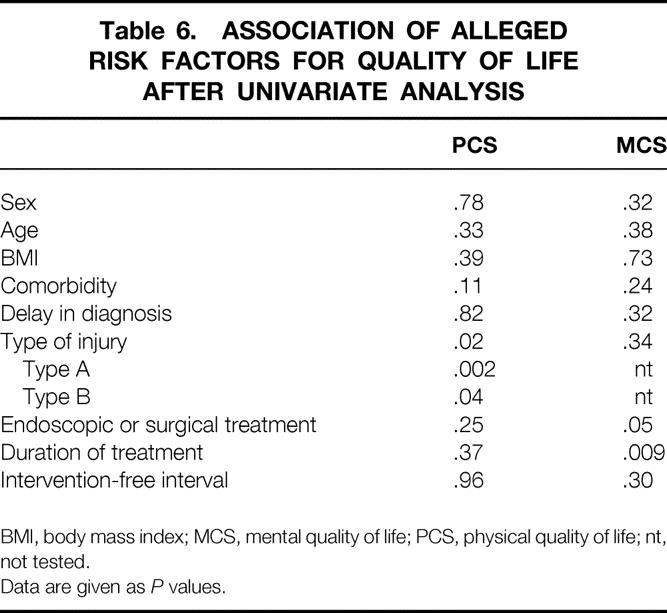

The median global score of physical functioning (PCS) of the patients with BDI was 38.4 (range 22–53), compared with a median PCS of the controls of 51.5 (range 18–64). The median global score of mental functioning (MCS) of the patients with BDI was 40.5 (range 22–54), compared with a median MCS of the controls of 54.9 (range 24–64). Univariate regression analysis to assess risk factors for a poor outcome showed that endoscopic treatment and duration of treatment both were prognostic for a worse mental (MCS) quality of life (P = .05 and P = .009, respectively) (Table 6). Further, the Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant difference for the PCS between the types of injury. Subsequent t testing showed that a type A lesion was associated with a worse physical outcome and that a type B injury was associated with a better physical outcome. For the mental quality of life (MCS), the type of the injury was not significant with the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 6. ASSOCIATION OF ALLEGED RISK FACTORS FOR QUALITY OF LIFE AFTER UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS

BMI, body mass index; MCS, mental quality of life; PCS, physical quality of life; nt, not tested.

Data are given as P values.

Multiple linear regression of variables with a P < .3 in the univariate analysis on the global MCS or PCS scale showed that a type B injury was the only independent prognostic factor for a high physical QOL. Further, the duration of the treatment (i.e., from the day of diagnosis until the last treatment) was independently prognostic for a poor mental outcome. Endoscopic treatment was not independently prognostic for a worse mental outcome by multiple linear regression.

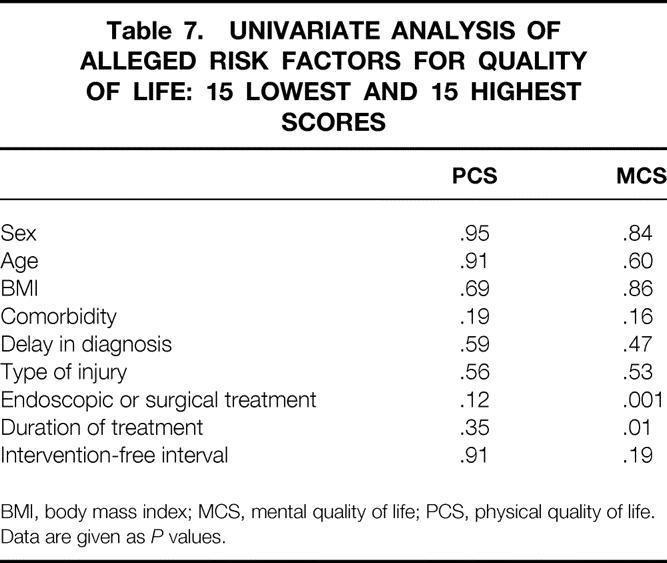

To obtain additional information about a possible explanation for our findings, the contrast between “better” and “worse” patients was increased by performing the same analysis on the 15 patients with the best and the 15 patients with the worst mental and physical summary score (Table 7). Again, the type of injury and the type of treatment used were not prognostic for a worse outcome.

Table 7. UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF ALLEGED RISK FACTORS FOR QUALITY OF LIFE: 15 LOWEST AND 15 HIGHEST SCORES

BMI, body mass index; MCS, mental quality of life; PCS, physical quality of life.

Data are given as P values.

Regression analysis confirmed the independent prognostic value of the duration of treatment (for a worse mental outcome) and type B injury (for a better physical outcome) (P = .02 and P = .04, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The long-term QOL of patients referred to a tertiary center for the treatment of BDI after LC was poor. However, aside from regular outpatient visits, patients had not sought the help of their general practitioner or a specialist for more than 5 years: this period was previously suggested to reliably represent long-term outcome because in fewer than 5% of patients do symptoms or an anastomotic stricture develop beyond this point. 16

Endoscopic treatment was performed in 69 patients and was functionally successful in 93%. The long-term results of surgery depended on the timing of the procedure. The overall success rate of hepaticojejunostomy was 84%, but in patients who underwent delayed reconstruction (suggested previously as optimal treatment 17 and performed in the latter phase of this study), success was achieved in 94%. Whether endoscopic or surgical treatment is indicated depends mainly on the type of injury and the time of detection, and the indications for both modalities are completely different. In 77 of 82 responding patients (94%), no physical or biochemical evidence of recurrent biliary problems was encountered. In previous studies, although with a shorter follow-up, comparable success rates were reported. 18–20

Despite this excellent objective outcome, long-term QOL was remarkably poor on both physical and mental scales. The QOL of patients with BDI was significantly decreased compared with the QOL of patients who underwent uncomplicated LC 24 months earlier and in healthy controls. To our knowledge, no comparative data are available in the literature regarding the QOL after BDI.

The severity of the injury and subsequent treatment (endoscopy or surgery) were thought to affect the long-term QOL. Patients with leakage from the cystic duct, for instance, generally undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC), during which an endoprosthesis is inserted to bypass the sphincter of Oddi. Six weeks later the stent is removed during a second ERC procedure, performed on an outpatient basis. The hospital stay is short, and from a physician’s point of view the burden is relatively limited. In patients in whom the CBD is transected and accidentally removed, however, generally the ERC can be used to visualize the distal portion of the biliary tree, and transhepatic cholangiography is required to show the proximal anatomy and to assess the full extent of the injury. 18 Reconstruction is planned at least 6 weeks later, and radiologic drainage procedures must be used in planning the optimal timing of surgical intervention. 17–20 Patients can often be discharged in the meantime; but, the hospital stay is obviously much longer and the physical and mental burden is considerable. However, by univariate and multivariate regression analysis, the type of injury did not predict QOL. We have no logical explanation as to why type B lesions were associated with a less-reduced QOL than other lesions. Considering the large 95% confidence interval, this finding may be the result of a type 2 error. For physical outcome, no other prognostic factors could be found, which is remarkable but in accordance with the lack of objective evidence for recurrent disease.

Whether patients were treated by endoscopy or by (major) surgery, mental and physical QOL was equally poor. Mental outcome was negatively influenced by the duration of treatment (i.e., the number of days between the time of diagnosis until the last therapeutic intervention;P = .009). Although significant on univariate analysis, endoscopic treatment appeared not to be an independently prognostic factor, probably because endoscopic treatment often takes at least 6 months, but in fact consists of repetitive 1-day outpatient procedures. It seems understandable that long-term treatment for a complication of what was to be a “minor” operation has great psychological impact.

Because QOL seemed only incidentally dependent on individual variables, possibly general factors that account for the whole investigated population might play an important role. Several factors should be considered. First, the method of testing seems adequate: the SF-36 is the most commonly applied and extensively validated generic QOL questionnaire available and was filled out at home. Second, these patients represented a regular population of patients undergoing LC for symptomatic gallstone disease in The Netherlands in terms of age and sex. 11 Further, patients were randomly referred from 45 different hospitals, with a wide variety in severity of the injury; this makes selection bias an unlikely explanation for our findings.

Even patients undergoing a minor procedure had to be referred to a tertiary center for treatment of a medical error. It was frequently noted that patients were disappointed about the occurrence of the injury and in particular about the delay in diagnosis, despite their reporting symptoms after the procedure, and the reluctance of the primary surgeon to discuss the procedural error and subsequent severe complication or even to acknowledge the error. It is known that most litigation in medical care results from failure of communication between doctor and patient rather than from the medical error itself. 21 In this series most surgeons did not discuss that the promise of a noninvasive approach with minimal postoperative burden was compromised in the patients, leading to time-consuming procedures and referral to a tertiary center. Further, treatment and follow-up in the referral center possibly focused too much on the physical results in terms of adequate biliary drainage rather than addressing the overall physical and psychological burden of the patient in detail.

A phenomenon recognized in QOL assessment in patients with cancer is the concept of “response-shift bias.”22,23 Patients with cancer tend to report a better QOL than expected on medical grounds, presumably because they learn to adapt to their increased symptom level or their impaired QOL, changing the internal standard of measurement. Patients undergoing LC are prepared to undergo a minor procedure with minimal morbidity, a short hospital stay, and a complete return to their daily social and professional activities within weeks. But after the occurrence of a BDI, patients are confronted with a prolonged hospital stay, referral to a specialized center, additional invasive interventions, and sometimes even relaparotomy. Possibly patients are not able or willing to adapt to their reduced daily health status because of the medical error that occurred. Many patients discussed at an early phase the possibility of malpractice litigation; this was eventually pursued by only 10% of the patients, probably indicating that no final settlement had been reached in the majority of cases. Generally, malpractice litigation is not common in the Netherlands.

It was recently suggested that the learning curve for LC is no longer relevant because the incidence of BDI remains stable at around 1.4%; in that case, an occasional BDI, accompanied by its sequelae, is inherent in this technique, which is increasingly applied in our aging population. 5,24 To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting QOL in patients who have been treated for BDI after LC. Using a well-established QOL questionnaire in randomly referred patients with various types of injuries, QOL after BDI was found to be remarkably poor both on physical and mental subscales. Further research about which factors influence QOL in these patients is warranted to improve patient care. Despite the high number of uncomplicated LCs, the sequelae of BDI mandate a critical indication for the procedure, as well as careful pre- and postoperative doctor–patient communication about potential procedure-related complications.

Discussion

Prof. M. Buchler: Another excellent paper from the Amsterdam Group which demonstrates new data that we have not been aware of so far, so congratulations. On the other hand, we are much disappointed about the data as you have shown, that the life quality after what you say adequate repair is so bad. Listening to what you have demonstrated, two things come to my mind: 1. Is the instrument you use, namely the quality of life instrument, to measure the quality of life, is that the right instrument, because we all experience these patients in our hospitals and if you surgically repair, they do feel well as far as we could evaluate so far. So, is this instrument the right instrument? The second question is: In your department endoscopy is a very strong force, as far as I know, so you treat these patients over months and even over years using stenting. I can just speculate that stenting these patients over months and years would decrease the life quality as instead doing a surgical procedure right away. This is just another hypothesis to explain such disappointing life quality outcome.

Prof. H. Bismuth: I have some concern about one aspect of your conclusion: when you said that the severity of the injury has no influence on the quality of life. One explanation could be that you put together different lesions: for instance, type A is a cystic duct leakage, which strictly is not a bile duct injury. Of course, these patients are very well treated by simple endoscopy, but they may be cured also by doing nothing. It is difficult really to compare endoscopic treatment for cystic leakage and surgical treatment for type D, which is the very severe injury.

For the second part of your paper, I agree with the first discussant. I understand why you observe the same abnormality in the quality of life, if by endoscopic treatment you have long-standing treatment. Quality of results is one thing, and quality of life is another thing, and what you show is that the only fact that the trauma is unexpected and is a supplementary disease created by the surgeon is for life a psychological injury for the patient.

Prof. A. Johnson: I too found these data fascinating. I think the two key questions are: What were the patients told before they had the operation in the first place? Were they warned about bile duct damage? How many had resolved their litigation problems? If litigation is still in progress, then many patients will not get better until the money has been paid out: then their quality of life dramatically improves! What should we tell patients if they should have the misfortune to have their bile ducts damaged? You refer to surgeons’ reluctance to admit the error, but do you have advice on how patients should be told?

Prof. B. Kremer: In your Amsterdam classification, I missed one parameter that is in my experience of high importance, the damage to the right hepatic artery. Did you not have this kind of patients, the full disaster?

Prof. D. J. Gouma (closing): Thank you for the kind remarks and questions.

The first question of Prof. Buchler concerning the SF36 quality of life questionnaire: this is the most validated quality of life instrument we have; it is used in different diseases such as chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer but also in evaluation of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We performed a study, which was presented 2 years ago for the Association, on day-care laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy with normal admission using the same quality of life questionnaire, and this instrument is still the best we have. Of course, we find it difficult to agree with the outcome because these patients do not have objective symptoms or findings, but this is the quality of life measured in these patients. Probably the questionnaire will miss a number of details which are important for these patients, such as litigation settlement.

Concerning your remark on long-term stenting, I think this is an important point, because it could be one of the reasons why these patients with probably ischemic lesions who are entering the hospital a few months after surgery and are indeed treated by endoscopic stenting for about a period of 1 year and have to swallow six to eight times the endoscope, have an impaired quality of life. This is probably also the reason that the only prognostic risk factor for poor quality of life is the duration of treatment. Presently, in our hospital, we have the discussion with the gastroenterologists, what the optimum timing is for endoscopic treatment, particularly in these patients with ischemic lesions. If 3 months or 6 months of stenting and dilatation are not helpful, it will probably not be successful after 1 year. I think in the next few years, we will reduce stenting to 3 or 6 months and earlier change for surgical reconstruction.

The questions of Prof. Bismuth about minor versus type D (severe) lesions. I did not want to compare the outcome of type A lesions with type D lesions; I wanted to summarize the long-term outcome of all bile duct injuries we have been treating. And, of course, there is a big difference in the severity of these lesions. The fact that surgery is doing well in type D lesions means that we are able to treat the most severe lesions as well as the minor lesions by the endoscopist. It does not mean that surgery is better than endoscopic treatment. Different lesions should have a different approach. I am still convinced after 160 patients, who have been treated initially endoscopically in our institute, with a 5-year successful outcome of 90%, that it is useful to treat these patients endoscopically in a first attempt.

I do not fully agree with the remark that type A lesions are not important. In our series only one patient died, but it was a patient with a type A lesion and severe biliary peritonitis. If these patients are not recognized early and treated adequately, they will develop severe septic complications.

Concerning the remarks of Prof. Johnson what you should tell these patients: this is part of the next study. The first study was to analyze quality of life; currently we are analyzing these patients again to see what kind of information was provided before surgery. What I have recognized so far during outpatient clinics is that many patients had insufficient information before surgery. Many patients did not have the information that a bile duct lesion could occur.

Litigation is only solved in less than 10% of the patients in The Netherlands. Most patients are not enthusiastic to start litigation immediately, but when they are still disappointed about the outcome after 1 year, they did start the procedure later and are still involved.

The percentage of litigation is a much lower than, for example, in the United States, and as recently shown by Moossa in case of settlement, the quality dramatically improves, just as you mentioned. Concerning your last remark, what to tell them, I should tell them the truth immediately. If patients are referred to our hospital and we are making a drawing of the bile ducts to explain the reconstruction preoperatively, they generally answer: I did not hear this before; I did not know that anything of the duct was missing. Most patients mentioned that they realize that these errors can occur, but they want to have the correct information.

The last remark from Prof. Kremer about the Amsterdam score; this is a score according to the severity of the injury of the bile duct, not including injuries of the right hepatic artery, but it is an important issue. We had only three patients with hepatic artery damage; in one we performed an embolization with necrosis of two segments of the right liver, which resolved spontaneously. In one patient it was quite difficult to do a repair because there was necrosis of the right hepatic duct associated with the lesion of the right hepatic artery. So, indeed, injury of the artery will be an important risk factor.

Once again, I would like to thank the Association to have the privilege to present these data.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Dirk J. Gouma, PhD, Department of Surgery, Academic Medical Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

E-mail: d.j.gouma@amc.uva.nl

Accepted for publication April 2001.

References

- 1.Fletcher DR, Hobbs MST, Tan P, et al. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography. A population-based study. Ann Surg 1999; 229: 449–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 1365–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keulemans YCA, Eshuis J, de Haes H, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: day-care versus clinical observation. Ann Surg 1998; 228: 734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1992; 215: 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvete J, Sabater L, Camps B, et al. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Myth or reality of the learning curve? Surg Endosc 2000; 14: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strasburg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 180: 101—125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacFayden BV, Vecchio R, Ricardo AE, et al. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The United States experience. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern KA. Malpractice litigation involving laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg 1997; 132: 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll BJ, Birth M, Phillips EH. Common bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy that result in litigation. Surg Endosc 1998; 12: 310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman JJGHM, van den Brink GR, Rauws EAJ, et al. Treatment of bile duct lesions after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gut 1996; 38: 141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keulemans YCA, Bergman JJGHM, de Wit LT, et al. Improvement in the management of bile duct injuries? J Am Coll Surg 1998; 187: 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physiccal and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1994.

- 14.Boerma D, Keulemans YCA, Rauws EAG, et al. A randomized comparison of endoscopic sphincterotomy with and without cholecystectomy. Interim results. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: A5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JEW. The MOS Short Form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 1988; 26: 724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raute M, Podlech P, Aschke WJ, et al. Management of bile duct injuries and strictures following cholecystectomy. World J Surg 1993; 17: 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schol FBG, Go PMNYH, Gouma DJ. Outcome of 49 repairs of bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg 1995; 19: 753–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponsky JL. Endoscopic approaches to common bile duct injuries. Laparosc Surg 1996; 76: 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brugge WR, Van Dam J. Pancreatic and biliary endoscopy. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regöly-Mérei J, Ihsz M, Szeberin Z, et al. Biliary tract complications in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 1998; 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer JE. The effect of litigation on surgical practice in the USA. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 833–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howard GS, Ralph KM, Gulanick NA, et al. Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Appl Psychol Meas 1979; 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sprangers MAG. Response-shift bias: a challenge to the assessment of patients’ quality of life in cancer clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rev 1996; 22 (suppl A): 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moody FG. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2000; 14: 605–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]